I’m Jordan Schneider, Beijing-based host of the ChinaEconTalk Podcast. In this newsletter, I translate articles from Chinese media about tech, business, and political economy.

This week I’m republishing a short article I wrote for the Stanford-New America DigiChina Project. They put together a 45-page report featuring original pieces from a ton of different scholars on everything China and AI.

I’m likely in Hangzhou this Tues and Weds, so if there are any readers that want to meet up, do reach out!

If you’re interested in translating for this newsletter (I’ve got a budget) or joining our WeChat discussion group, add me at jordanschneider.

A Chinese ‘AI Winter’ on the Horizon?

“DougLong,” an anonymous investor and entrepreneur in AI, reflecting on Gary Marcus’ recent book Rebooting AI, points to three big issues with AI in 2019. First, good data is hard to come by. Second, test training data doesn’t line up with actual operating environments. And third, “to B” companies having a hard time retaining AI talent for the long haul.

While there is little available as to the DougLong’s true identity, the piece was published by respected tech media outlet and consulting firm Jazzyear, giving it a large audience in a country where pseudonymous commentary is a common tool of discourse. On the first issue, the dearth of good data, DougLong quotes an anonymous old hand in the data industry who just joined an AI startup and has been sorely disappointed with AI’s effectiveness in the marketplace.

When customers see how many terabytes or petabytes they have in their database, they think they have big data…But once we get down to work, the data is basically useless. Some fields are misentered, others are too sparse. Once you finish cleaning it up, the data leads to totally logically unsound conclusions, with no chance to do any deep learning…

For instance, once I did a fault detection project for a Zhejiang tire factory. … Hundreds of thousands of tires were piled up in open air collecting dust, so we had to hire people climb these tire mountains, clear away the dust, and write down the tires’ model and batch numbers and their faults. But on hot days—dirty and tired—some workers just lazed around and wrote up fake data…

The fact that some data sources are borderline illegal is an open industry secret. In some industries where information security measures are weak, it’s most cost-effective to find some internal personnel to just copy off full hard drives.”

DougLong used an analogy to Chinese medicine to explain the importance of AI engineers sticking to one project for an extended period of time. “Since the theory around deep learning isn’t complete and it’s impossible to understand the operating mechanisms of algorithms, the success of various adjustments and improvements depends on experience combined with luck, and capabilities are hard to replicate quickly. It’s like learning Chinese medicine. For a novice practitioner to mature into a high-level talent, one must complete many cases and encounter many conditions. Old Chinese medicine practitioners accumulate personal experience of successes and failures, depending on cases and insights to accumulate experience in the ‘four methods of diagnosis.’”

But the way the industry is set up makes it difficult to support top talents, especially in “to B” businesses. DougLong writes that most projects require specialized, non-scalable work, and many senior people already have families and don’t like long business trips. Said one cloud sales rep at a BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, or Tencent) firm:

“One time a customer asked us to do a proof-of-concept for an AI project and wanted some high-level people on it. So I pulled out all the stops and borrowed a few people from AI research institutions. They went on-site for six weeks, but the project didn’t succeed. When I tried to get them again, they wouldn’t answer. They don’t like doing client projects, and what’s more, they can’t use that time to publish papers. And with such expensive outlays of human resources, there’s no guarantee of standing out in the yearend results.”

Building Foundations, or Seeking Handouts?

This past August, a handful of senior investors reflected on the challenges facing domestic AI startups at a conference organized by the digital media outlet Lieyun Net.

Liu Shui, investment director at the incubator CAS Star, encouraged startups to focus on the tech underlying advances in AI. According to Liu, “AI chips are the main battlefield, regardless of whether you’re pursuing hardware or algorithms.” But he sympathized with the plight of entrepreneurs in the space. “Even if your technology is top notch, it’s very difficult to commercialize a product. First, finding funding is hard. And second, there isn’t a lot of support to help transitioning from tech to a viable product.” He also admitted that China lacks investors with a background in AI to help back the best startups.

Wang Sen’ao, an executive at Lieyun Net, advised AI startups struggling to find cash to “change yourself to let the government back you unconditionally.” It’s possible for a startup afer a year of operation to get subsidies approaching U.S. $1 million, but doing so is different than pitching yourself to private sector investors. According to Wang, firms need a model that aligns both with government aims and their own interests. Doing so requires entrepreneurs to “push [government] guiding documents from top to bottom,” because, Wang says, when it comes to national industrial policy, State Council instructions filter all the way down, and their administrative measures and implementing rules require rapid study.

Overall, independent Chinese AI firms are facing similar headwinds to western ones as they struggle to commercialize their technology. It remains to be seen whether government support is a difference-maker. Ultimately, DougLong leaves readers with the following advice: “Give up fantasies, buckle down, and stay strong to get through the winter.”

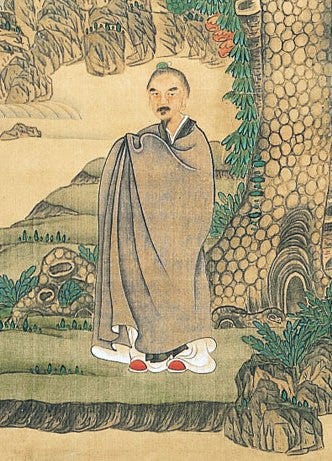

Chinese Painter of the Week: Chen Hongshou 陈洪绶

Symbol-laden still life painting was never really a thing in China. But does this man look like someone who is going to blindly follow tradition?

Chen lived in the late Ming, in the first half of the 17th century. From the Met:

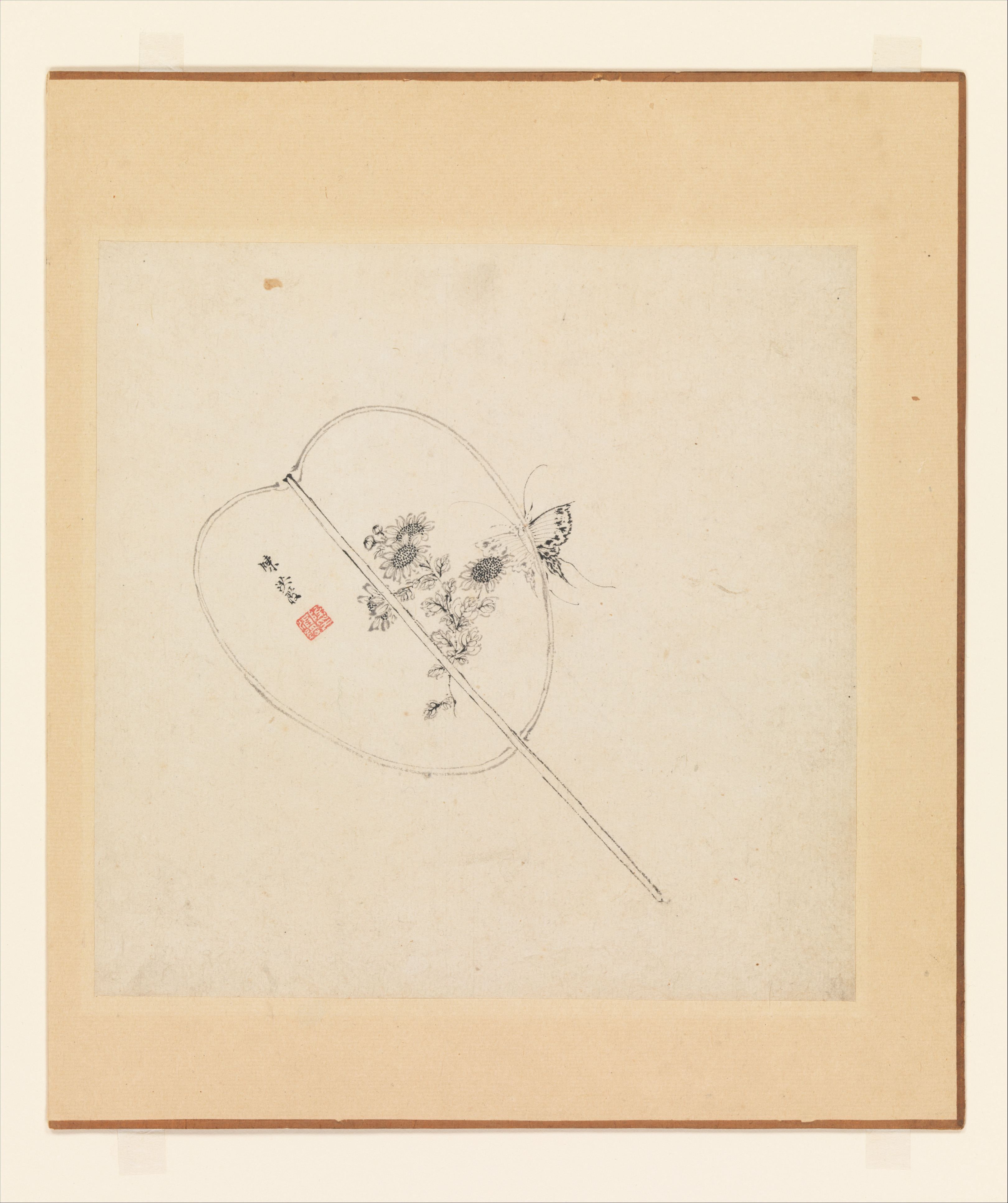

This album plays on the theme of reality versus illusion. The moon is reflected in a basin of water, a flower is next to its image in a mirror, and a butterfly is attracted to chrysanthemums painted on a silk fan. Chen emphasized the multiple levels of his artifice on this album leaf by incorporating his signature within the composition of the fan painting and by screening one wing of the butterfly with the fan, forcing us to view the insect through the painting as well as through the medium of painting.

There is no precedent for these symbolic still-life subjects in scholar painting. Instead, these highly sophisticated images, which relate to the ornamental designs found on deluxe crafts of the time, including molded ink cakes, printed stationery, and the carved decoration of Yixing ceramics, reflect Chen Hongshou's early involvement in creating woodblock illustrations for novels and dramas.

Here’s the fan one.

He painted these when he was 21 years old. Ming Dynasty Stan Lee I’m telling you.