CAC Stressed About China's Feelings, TikTok + Indonesia Protests, Chips in Costa Rica and Poland?

Friday bites!

CAC Stressed About China’s Feelings

Last week I stumbled on a fascinating new release from CAC that gives a sense of just what the Chinese government is worried its citizens are feelings. Cyberspace Affairs Commission pushed out a new iteration of its years-long content purge campaign, Qing Lang 清朗, that targets “malicious incitement of negative emotions” (恶意挑动负面情绪). On the surface it reads like a regular cleanse of party criticism in the name of boosting “positive energy,” but this go-around feels even weirder.

Em from the brilliant substack Active Faults delivers the Straussian read below. Block quotes are translated from the Sept 22 CAC post itself, and the commentary is Em’s.

To address problems such as maliciously inciting confrontation and promoting violent and hostile sentiments—and to foster a more civil and rational online environment—the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) has recently issued a notice launching a two-month nationwide “Clean & Healthy: Special Campaign to Curb the Malicious Stirring of Negative Emotions.”

A CAC official said the campaign will focus on social networks, short-video and livestreaming platforms, conducting comprehensive inspections of key features such as topics, rankings, recommendations, bullet comments, and comment sections, and will target the following issues:

1) Incitement of extreme and contrarian feelings between groups.

Exploiting viral news stories to forcibly tag or stigmatize people by identity, geographical area, gender, etc., thereby stoking conflicts between groups. Using media content, stand-up comedies and sports events to egg on “fan-circle” factions to maliciously belittle others, attack, abuse, or organize mass reporting. Certain ACG subgroups and “trolling youth” communities inciting confrontation or even doxxing, or teaching how to buy and sell doxxing services.

I’m hardly surprised at this hyperspecific whip-cracking. Chinese entertainment has seen some of the most radically feminist movies, comedy sets, and drama series in the past two years alone than all previous years combined. Beyond entertainment, numerous high-profile news stories in 2025 provoked intense discussions among members of the public, like the lead poisoning controversy in a Gansu kindergarten, or the sexual harrassment incident at Wuhan University. General discontentment and mistrust of the authorities are boiling over, and this wave of Qing Lang needs to quell them with renewed force.

2) Spreading panic and anxiety.

Fabricating fake news about disasters, dangers, or police incidents that could affect public safety; forging government notices. Peddling supposed insider knowledge via spliced clips or coordinated account networks to concoct and spread rumors about the economy and finance, people’s livelihoods, and public policy. Inventing or distorting the causes, details, and progress of events to post sensational conspiracy theories. Assuming fake identities as “gurus” or “experts” to hawk anxiety and sell courses or products related to jobs, relationships, and education.

Problem 2 is the “amplification of panic and anxiety” in the form of “fake news”, like fabricating “insider knowledge” of upcoming policy changes or economic trends. This feels akin to an attempt at rebuilding public trust in party competence that will end up, probably, achieving the complete opposite.

3) Stoking online violence and brutality.

Planning or acting out staged fights, deliberate harassment, etc., and advocating “violence against violence” (以暴制暴). Sharing graphic, unedited images of bloody and terrifying scenes, or posting shocking videos involving animal abuse or self-harm. Using AI synthesis, video editing, or image splicing to glamorize violence and create a lurid, horror-seeking atmosphere. In livestreams, using self-harm, self-abuse, “hit-someone challenges,” or brandishing weapons as gimmicks to gain followers; organizing online brawls and livestreaming mutual insults or physical fights arranged offline.

Problem 3 is the “incitement of violence and hostility”, which I suspect is a jab at the dopamine-inducing micro-dramas (短剧) on short-video platforms. They normally feature a simple but satisfying plot of power reversal, involving an underdog protagonist getting avenged or becoming successful. In the past year, this type of content has garnered an onslaught of profit and internet traffic, so much so that long-form entertainment content suffered a heavy blow to their viewership. What the micro-drama hype entails is what they fear: growing disillusionment in recovery. Widespread “laying-flat” sentiments. Dismissal of any real hope of prosperity. None of this “negativity” is being “incited”, but rather articulated. The choice of vocabulary is trying to frame genuine, organic expressions of vexations as secondary and induced, hence unrepresentative and indicative of (perhaps foreign) foul play.

4) Over-amplifying defeatism and pessimism.

Concentrated posting or one-sided promotion of absolutist, negative claims such as the “futility of perseverance and education” (努力无用论), or other absolutist, world-hating views (‘绝对化、消极化论调’). Maliciously re-reading social phenomena to over-inflate isolated negative cases and use them to promote defeatism. By churning out so-called trending terms, memes, stickers, and quotable lines, excessively self-denigrating or saturating feeds with listless, gloomy content that spurs imitation.

The last focus area confirms the above theory. It promises to rid the internet of “excessive pessimism and passivity”, namely content arguing for the “futility of preserverance and education”, or anything nihilistic and world-hating. There is to be no complaints about the state of the country and the quality of civilian lives. Just trust the process everyone!

Dispatch from Indonesian TikTok: How ByteDance deals with contentious politics around the world

Irene Zhang reports:

The world’s fourth most populous country currently finds itself in a once-in-a-generation political crisis. Indonesia has been riled by large protests since earlier this year. Beginning in February, students and civil society members organized protests to oppose President Prabowo Subianto’s budget cuts to education and the rising role of the military. More recently, a controversial measure to award lawmakers $3000-per-month housing subsidies, more than four times the country’s average monthly salary, has led to an outpouring of public anger over corruption. The protests suddenly gained momentum when, on August 29, a police vehicle killed 21-year-old delivery driver Affan Kurniawan in Jakarta. As of September 2, ten people have died in violent confrontations with police and security forces. Amid all this, Prabowo travelled to Beijing to attend the WWII commemoration military parade and meet Xi Jinping — despite saying last week that he would cancel his China trip to address domestic unrest.

Indonesia has the world’s largest TikTok user base, at 157 million — more than half of its 285 million population. Indonesians spend big on TikTok Shop, generating $6.2 billion in gross merchandise value in 2024. ByteDance has worked hard to cultivate the Indonesian market, acquiring a local e-commerce competitor and navigating complicated local government relations in the process in order to expand its market share. Indonesia is an indispensable part of its international outlook and growth prospects.

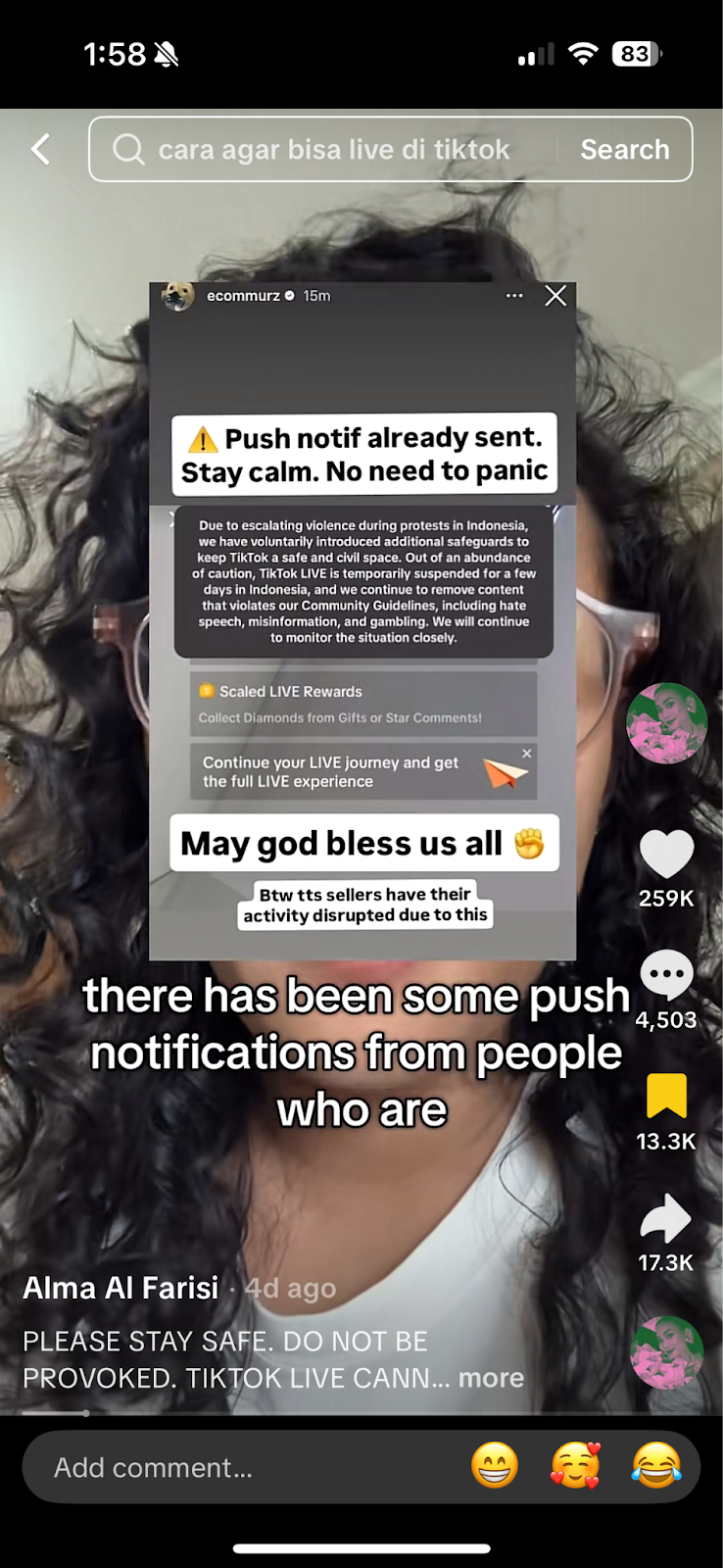

What happens when millions in your platform’s biggest user base start posting videos about political conflict and violence? On August 30, TikTok, along with Instagram, turned off livestreaming in Indonesia and sent this notification to creators in the country:

Livestreams on the platform were down from August 30 to September 2: during this time, an angry mob burned down the regional parliament building in South Sulawesi’s capital Makassar, finance minister Sri Mulyani’s home was looted, and police tear-gassed students at two universities in Bandung. Young Indonesians are heavily reliant on TikTok for news. Amid reports of TV stations being taken off air and government pressure being applied to traditional media, even more people are turning to TikTok to follow the events.

Indonesian TikTokers are still trying their best to televise the revolution without livestreams. They’re calling on international users to comment using viral words like “labubu dubai chocolate” on their videos discussing Indonesian politics, so as to fight alleged algorithmic suppression of anti-government content. They are also making very creative edits out of protest footage to fill hashtags like #demodpr (“demo” is Indonesian slang for protest, and DPR is the acronym for the Indonesian House of Representatives, the target of much ire), #indonesiagelap (“gelap” means dark), and #resetindonesia:

Turning off TikTok Live in Indonesia for four days probably cost ByteDance millions of dollars, but from its perspective, it was a worthy trade-off to maintain good relations with Jakarta’s politicians. On August 27, just days before Affan’s death rocked the massive archipelagic nation, Indonesia’s government summoned Meta and TikTok representatives to discuss content moderation. Deputy Communication and Digital Affairs Minister Angga Raka Prabowo accused TikTok and Instagram of stoking anti-government protests, urging platforms to remove content proactively. The government denies having pressured TikTok to turn off livestreaming. Even then, Indonesian creators on TikTok report that their videos about protests and anti-government action seem to be suppressed by the platform.

When it comes to censorship and regulating digital content, ByteDance’s relationship with the Indonesian government stretches back even further. Its lobbying in Jakarta faced a rocky situation in 2023, when the country briefly banned TikTok Shop in order to protect the livelihoods of local market vendors. ByteDance then acquired a majority stake in local-grown online retailer Tokopedia in order to comply with regulations and go back online, though the aftermath of the merger has been troubled. In September 2023, TikTok signed a memorandum of agreement with Indonesia’s General Election Supervisory Agency (known as Bawaslu) to moderate content in the run-up to the general election in early 2024, which elected President Prabowo. A Freedom House report shows that Bawaslu and TikTok collaborated to align the platform’s community guidelines with Bawaslu’s goals. Scholars of Indonesian media and politics have long identified networks of digital propaganda on social media platforms, including paid pro-government influencers supporting Prabowo — and his predecessor, Joko Widodo — that aren’t dissimilar to China’s “fifty-cent army”. Prabowo’s own campaign for president more directly benefited from TikTok, where the former general’s goofy dancing videos gained virality.

Online leaders of the protest movement in Indonesia have, as of September 3, formulated “17+8” demands. The evolving situation is a reminder that TikTok’s political troubles don’t end with Washington: even if it exits the US market in the near future, it will continue to deeply shape politics around the world.

Semiconductors in Costa Rica? Poland?

Lily Ottinger reports:

Last month, I attended SEMICON Taiwan, a semiconductor trade show held annually in Taipei. While Taiwanese companies had the largest presence, the exhibition also included a hall of Chinese companies, as well as pavilions for democratic nations hoping to attract new investment from Taiwanese partners.

The Chinese booths were relegated to a single corridor with a low ceiling, separated from the main exhibition halls. When I tried to interview representatives of these companies in Mandarin, I was met with extreme skepticism — although booth workers were eager to take candid photos of me, presumably for their internal write-ups of the conference.

Seeing as my questions about supply chains and provincial government support were going nowhere in the China hall, I decided to check out the democratic friendshoring candidates instead. Here are the three countries that impressed me the most.

Poland

I’ve written about Poland’s advantages as a semiconductor manufacturing location before — the country has a high quality, decentralized university system which churns out tens of thousands of stem graduates annually; the population is highly proficient in English, and many people become fluent in a third language in university; the country has fantastic transportation infrastructure and is right next door to TSMC’s new Dresden fab.

When I spoke to Arkadiusz Tarnowski, Deputy Investment Director of the Polish Investment and Trade Agency, I learned that the Polish government has a history of successful industrial policy. Government support helped convince LG to manufacture EV batteries in Poland, and today, Poland is the world’s second-largest lithium-ion battery exporter after China.

While the EU sets regional ceilings on public aid for industrial development projects, Poland has the highest limits in the EU. Companies can reimburse up to 70% of their investments in Poland on their taxes, and there are grants available for “high-quality” investments that meet certain criteria. One native Polish company that receives EU funds is VIGO Photonics, which manufactures infrared detectors for NASA, medical, and industrial applications, as well as epitaxial wafers. According to VIGO representative Karolina Sałajczyk-Stefańska, the company was granted around US$120 million in EU support for their HyperPIC project on the condition that they would invest 1.5 euros for every euro of public aid they received. If the project succeeds, Poland will be home to the world’s first foundry for mid-infrared photonic integrated circuits.

In 2023, Intel announced an investment of 4.6 billion euros to build an assembly and testing plant in Wrocław. Poland didn’t cinch this deal by promising 0% tax rates or third-world wages. In Tarnowski’s words, “It’s not about the money, it’s about the environment,” and Poland is poised to succeed thanks to long-term investments in education and infrastructure that have already borne fruit.

Correction: Intel announced in 2025 that they would not move forward with their investment in Wrocław, though this had less to do with Poland than with Intel’s financial difficulties.

Czechia

The Polish representatives plied me with coffee — the Czech representatives offered me beer.

Czechia’s strategy for attracting investment is not specific to semiconductors, but also targets environmental technology, space research, and AI. Since the EU determines investment rules, it’s difficult to offer blanket incentives like grants, so the Czech government is instead offering case-by-case “custom” incentives to attract manufacturing investment.

A side effect of this regulatory scheme is that EU countries are not fiercely competing against one another to cinch deals, but rather specializing in different areas of the supply chain. Czechia hopes to manufacture chemicals and other inputs for TSMC’s Dresden fab, forming a triangular semiconductor cluster that includes Poland.

There are some cash grants available for strategic products like semiconductors, but approval is not automatic. After an application is checked by CzechInvest (a government-affiliated agency tasked with facilitating foreign investment), it is sent to the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Grants for strategic investments must then be approved by all ministries of the Czech government in a plenary session. The representatives I spoke to explained that this mechanism is a result of the EU-imposed ceiling on state support. Since there are strict limits on industrial policy spending, the government has to be choosy about which projects get funding. The CzechInvest representatives were confident that bureaucracy would not hold back investment, and to their credit, the agency appears well-funded and well-staffed.

Costa Rica

Costa Rica wants to become a regional hub for semiconductor manufacturing, and in March of 2024, the country announced a comprehensive roadmap for semiconductor success. Under this strategy, Costa Rica is offering chip manufacturers a 0% corporate income tax, 100% exemption from tariffs and VAT, and reimbursement for employee training costs. Simultaneously, the government is investing in the educational system, particularly in semiconductor expertise, bilingualism, and electronics R&D at the university level.

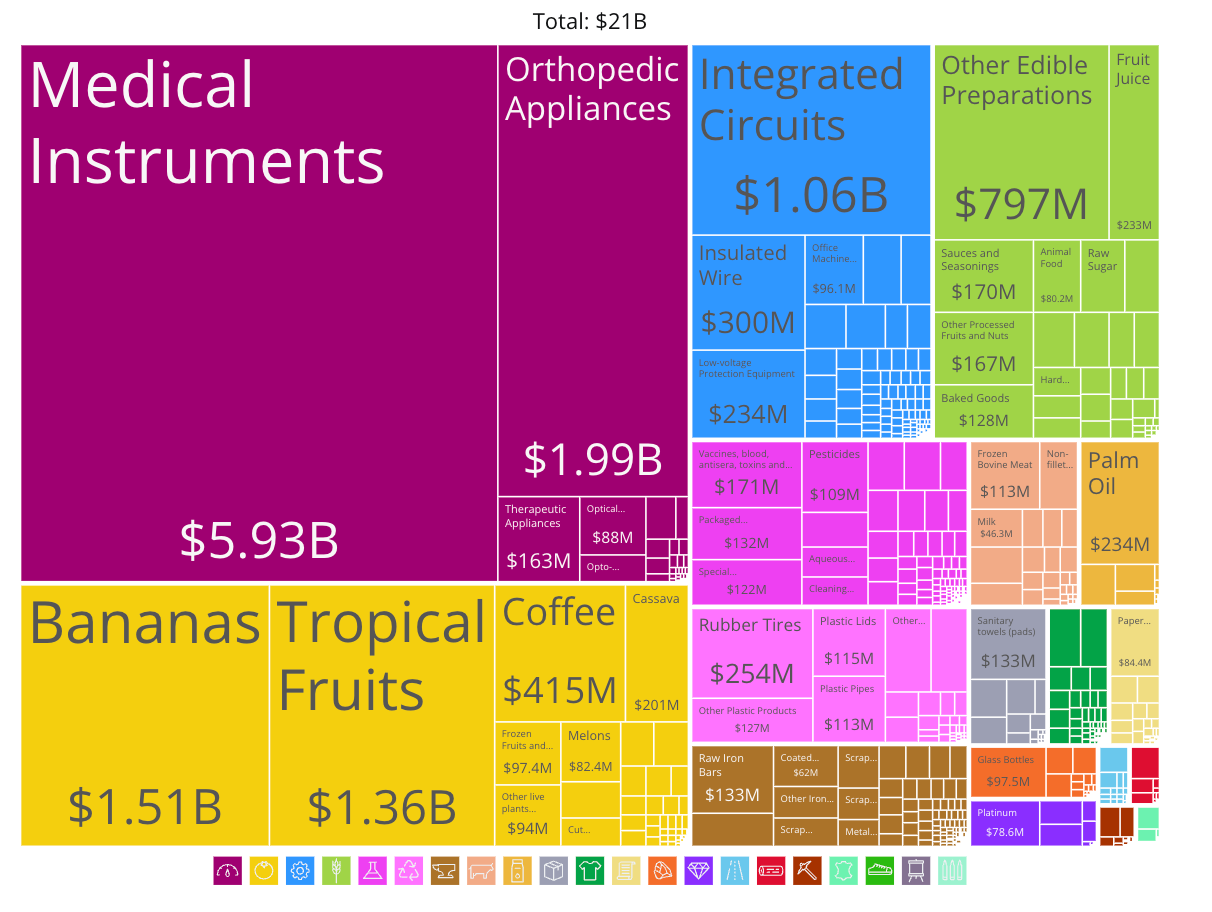

Since 1982, Costa Rica has successfully attracted foreign manufacturers with similar tax mechanisms under its free trade zone regime (Regimen de Zonas Francas), and today, Costa Rica’s most valuable exports are medical instruments and orthopedic appliances, not coffee or pineapples.

Intel has had a presence in Costa Rica since 1997, though its activities have been limited since 2014. That year, the company closed its primary assembly and testing plant in Costa Rica and moved operations to East Asia. At the time, Intel’s products accounted for 6% of Costa Rica’s GDP. Intel didn’t cite specific reasons for closing the plant, but workforce quality and distance from other parts of the supply chain are clear areas where East Asia comes out on top. From this experience, Costa Rica appears to have learned that their incentives need to be extra juicy if they want to land deals. As chip companies increasingly seek to democratize their supply chains, I’m hopeful that Costa Rica can expand their share of the pie.

Thanks for thoughts. About Poland our company VIGO Photonics doing great job. Intel decide to investment in 2023 but in 2025 resign after bad financial situtation in company. We hope they chnage their mind.

Costa Rica is definitely one of the best places in the Western Hemisphere for chip packaging. Unfortunately, Intel is shutting down its packaging and (further) consolidating its packaging in East Asia. Hopefully, incentives will align that allow another company to pick up where Intel is leaving off and supply much-needed conventional packaging services for the US market. https://latinamericanpost.com/business-and-finance/costa-ricas-intel-exodus-and-the-fight-to-save-its-silicon-dreams/