ChinaEconTalk: Huawei's Managerial Mojo and What I Learned in 2018

Happy New Year everyone!

First up are two articles on Huawei and real estate policy. What follows is an essay of Jordan’s on what he learned in 2018, aping in form Dan Wang’s annual posts. Most of it is tangentially related to China so I hope you find it interesting. In the coming weeks we’ll be covering the rise of Douyin (Tik Tok in the west) and the death of ride-sharing juggernaut Ofo.

Add us on WeChat!

How Huawei survived thanks to western management techniques, and why Chinese people see it as an inspirational company

A Silent Ode

一曲无声的赞歌

Written by the anonymous “Boss Dai” — 戴老板 Dài lǎobǎn

This 10,000-word article shared over 100,000 times tells the story of just how important western business practices were key to Huawei’s development as a firm. This story echoes Tyler Cowen’s recent Bloomberg Businessweek piece that argued one of the most underappreciated developments of the past thirty years as been the transfer of managerial know-how from the west to the rest.

Certain elements of Huawei’s development were unmistakably Chinese. CEO Rén Zhèngfēi’s 任正非 speeches featured references to Maoist slogans like “go to the countryside,” and he utilized corporate culture strategies like encouraging self-criticism to dampen employee ambitions. Yet as Huawei hit a crisis point in 1998, Zhengfei decided he needed to drag his company into the modern world, and started to model his firm after western best practices, whatever the cost may be.

His first move was to reach an arrangement with IBM to have the firm send seventy consultants over to Huawei for five years at an enormous $500/hr for a total cost of 2 billion yuan ($291 million). When faced with resistance, Ren declared, “whoever resists change will have to leave Huawei!”

Over the subsequent years, Huawei modeled more and more of its business after western best practices. “Huawei’s product development system is designed by IBM’s help, the human resources system is designed by Hay Group, and the organizational structure is designed by Mercer Consulting. The sales system was designed by Accenture, and the supply chain system was designed by IBM…” and so on. Huawei ultimately “is a company that is very jealous of the United States, but it is also a company that has learned to grow up from the United States.”

Yet the article goes on to say that there are still aspects of Huawei that are typically Chinese, primarily the legions of talented yet affordable engineers.

The piece concludes:

Some people are wondering these days: Why do the people love, support and support Huawei so much? The reason is simple: ordinary people may not understand GSM, and they don’t know what IPD is, but they know that Huawei’s achievements are one of the best things in our nation, representing the hard work, sweat, and wisdom of the Chinese. If someone points to his nose and says, ‘You have developed to the present by theft,’ this is undoubtedly an insult to every one of us.

Huawei’s experience tells us that China massive ranks of engineers, under an advanced management system, can renew vitality. This vitality will wipe out all the paradoxes of ethnic, national, and cultural gaps, so that China’s industry can really compete with the best in the world. With 30 years of practice, Huawei has taken the lead on the issue of whether or not the Chinese are capable. This is a silent ode.

By generously treating the struggles of each individual and releasing their vitality with a scientific system, the Chinese will continue to create miracles. Just as the company develops in this way, so can the entire nation.

Over the past week I’ve been introducing myself as a Canadian to see what sort of responses I’d get. My favorite response was in PUBG when someone said “Oh don’t worry, we won’t curse you! 中国人的素质很高! (The Chinese are high quality people!) The only people who curse on PUBG are the Japanese.” He then asked me if I spoke Canadian (“加拿大语”).

An update on the Canada Goose saga: the Beijing flagship store opened this weekend and sold out of coats.

(Credit: The Beijinger)

The problems left unsolved in land management

Land doesn’t have to be state-owned: New opportunities for China’s urban development

土地不再”必须国有”,城镇化或迎来机遇

By Zǐ Mù 子木, a Chinese real estate analyst who has written extensively on government land and housing policies

This analysis is based on the latest draft regulation on the management of China’s land, which was announced by the National People’s Congress on December 23. The urban land in China is largely owned and managed by the state, but there is also a large amount of land owned individually by indigenous people and collectively by local villages. This distribution of ownership is often the most controversial issue during the process of urban development in China, when the government needs to merge new land from villagers to support city sprawl.

Zimu estimates that the available residential rural land accounts for nearly 37 percent of the current urban land. The author believes that this draft signals that the government encourages private companies and individuals to invest in urban development and the local economy by being allowed to directly trade with local owners. Additionally, he argues that this draft law has left two problems unsolved: first, when the supply of land in the market increases, the economy, which is greatly driven by the housing sector, will be seriously affected. Second, there are many illegally built apartments on rural land, a difficult problem for the government to quantify or regulate.

Related Readings:

楼市重磅:不再“必须国有”,集体土地直接入市!Doesn’t Have To Be State-owned: Collectively-owned Land Can Trade in the Market

非农用地不再“必须国有”!那么小产权房能转正吗?Illegal Apartments on Collectively-owned Land — Can they be Legitmized or Not?

What Jordan learned in 2018

A lot of Mandarin

I’ve been studying Mandarin actively about 15 hours/week and passively another 20/week for a year and a half now. On any given day, command of spoken Chinese can range from that of a perplexed toddler to a precocious high school student. It’s a mental whipsaw as in different circumstances the percentage I’m able to comprehend of what’s going on around me swings dramatically.

For listening and speaking, short, specific commands or questions and conversations with a group of native speakers who share context I don’t (e.g., a handful of colleagues discussing their work) is the hardest. But if I know the vocab of the topic at hand, or someone is speaking directly to me and willing to slow down and respond to my requests for clarification, I can punch far above my weight.

For instance, I’m now acting in the PKU’s production of Hamilton (I’m the only foreigner and am playing James Madison/Hercules Mulligan). Sometimes when I get a specific stage direction (“turn 90 degrees to the right after Angelica sings the high note”), I have no idea what’s going on. But when talking one on one with a cast member who had just read Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia about political philosophy, I can go real deep without much of an issue. Feeling like an idiot one moment and a functional adult the next is a real exercise in patience.

My mandarin’s now good enough that I can consume tv, movies, and modern theater made for adults so long as I have my phone out to look up the occasional word. Even so, I often find myself unconsciously filling in the blanks of what’s going on around me. At a stand-up comedy show, for instance, I may think I know what the joke is and laugh at the punch line, but a misunderstanding of one keyword will have me thinking the inverse. However, the fact that a fair amount of jokes are lifted from Netflix specials helps!

In hard copy with no technology to help me, I’m functionally illiterate. But using Pleco’s reader to look up the characters I don’t recognize I can read at maybe half speed with 90% comprehension of what I could do in English. Using google translate plus ZhongZhong for confusing phrases bumps me up to 80% speed and 95% comprehension. Fiction and poetry are still beyond me. Reading interesting previously untranslated Chinese is thrilling and why I started this newsletter in the first place. However, I miss the ability to scan a book for what’s interesting, or google a topic and quickly evaluate what links are worth clicking.

Just to get to this point, I’ve put in thousands of hours of ‘dumb’ time, memorizing flashcards and having inane conversations with tutors who correct my bad pronunciation at every turn. (Though getting to engage with etymology through Outlier Linguistics’ pleco add-on has been fantastic. Who knew that the word for “fragile” 弱descended from a 3000-year-old character of a guy peeing?)

Thanks to the Yenching Scholarship, I’ve had this luxury to work on my Chinese, but with the same time investment, I could have been professionally fluent in Spanish and French, learned a programming language, written a TBI memoir, or read a hundred more books.

So is it worth it? Having spent time in Spanish-speaking countries with Spanish that’s much better than my Chinese is now, I find being in China much more stimulating. While in Beijing compared to, say, Mexico City I grasp a lower total percentage of what’s going, the difference-ness of what I do understand is far weirder than what the western world could offer up. From the parallel cultural tradition wholly separate from Athens, Rome and Jerusalem, to a communist state and a society that has suffered whiplashes of modern society more severe than anywhere else in the world, to a market large and developed enough to support enormous tech firms and cultural ecosystems, China just has so much more that’s new and challenging for me to digest. Learning Chinese has allowed me to stretch my mind in directions I didn’t know it could go.

Chinese Landscape Painting

Take, for instance, Chinese landscape painting. Back in the US I put in some time learning how to draw, and always thought ink painting looked cool. After posting on WeChat that I was looking for a classical Chinese painter, I got connected with a 30-something professional from Luoyang who moved to Beijing after art school and speaks no English.

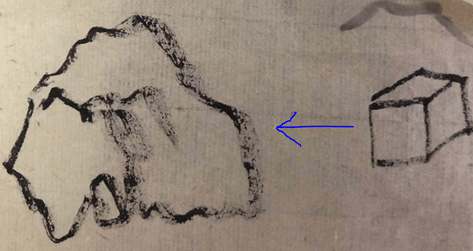

He paints super traditional stuff like this:

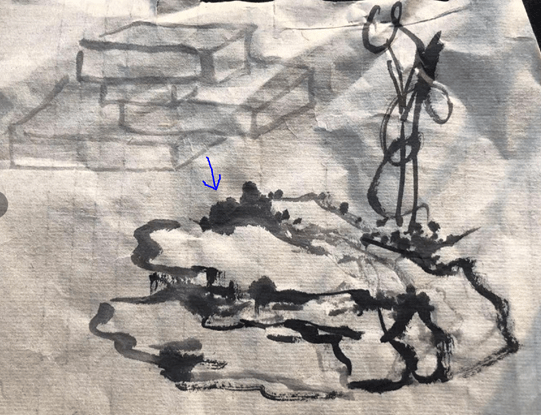

And more modern stuff like this:

The first hurdle as a Westerner to understanding and creating Chinese painting is coming to grips with the brush. Unlike western brushes, Chinese brushes don’t return to form after each stroke and can generally hold more ink and water. This builds in a certain amount of seeming randomness that you learn to control over time.

One of the first frustration points I had with Chinese landscape ink painting vs. drawing or acrylic is the inability to erase or paint over. These ‘mistakes’ within certain bounds are the point, as you’re aiming for变化 or variation, not realism or something copy-pasted from whatever master you’re modeling. You develop your skill by adapting and responding to whatever randomness the brush creates, presumably until the point where you have enough control to manufacture randomness yourself.

When learning Chinese painting, you’re also engaging with multi-millennia tradition far more continuous than western art’s. One day you’re learning how to paint a tree in the style of a Song dynasty master, and the next can look at how five other painters from later dynasties who also put in the same hours you did learning that Song tree made their spin on it. In contrast, if you were taking a western studio art painting class, you’d spend approximately zero time looking at Byzantine-era art. Understanding how artists model their works after past masters while at the same time evolving their styles to fit court tastes, philosophical trends, what other scholars think is tasteful, or just how they feel that day is far more a part of Chinese than western art criticism.

Chinese trees sort of make sense to me. After all, to a western eye, they look like stylized trees and by and large correspond to various species. But rocks have been a real conceptual challenge as space and perspective are conceptualized and abstracted differently.

For instance, as my teacher showed, painting a square-shaped rock doesn’t look like how I’d outline and shade a square in a studio drawing class but rather something more like this:

Very few painters in the Chinese tradition have ever painted the underside of a pavilion even if it was placed on the top of a mountain. Painting objects in proper western perspective as the eye would see a scene misses the point, as it’s an artist’s job instead to, as Shen Kuo wrote, view landscapes “from the angle of totality to grasp the whole.” This means that, as Michael Sullivan explains, “the painter should paint what he knows is there, not just what he sees from one place.” I don’t really get it, but I know enough that I have to retrain my mind and eye to imagine the world in a new way.

Perhaps the deepest lesson has been that of the importance of the latent mood you’re bringing to whatever task you undertake. Most classes we start by shutting our phones off, sipping whatever tea my teacher’s friends sent him that week, and chatting about what his two-year-old has been up to. But every once in a while, when one of us is a little rushed, we skip the tea. Those days, and when practicing when stressed, it’s obvious in the paintings that I don’t control my brush as well, and my compositions aren’t as natural. The best analogy that comes to mind is how Conor McGregor’s punching power and accuracy comes not from amped up rage but how loose his muscles are.

AI, Chess and DOTA 2

My whole life I’ve had a conflicted, guilt-ridden relationship to video games. Growing up I was constantly told they were a waste of time and had my hours playing games rationed out. As I wasn’t allowed to own first-person shooters, I ended up surreptitiously installing Counterstrike on the living room computer and waking up in the middle of the night to play. Getting caught felt like an episode of Big Mouth.

Mostly, however, I fell for competitive real-time strategy games like Warcraft 3, enjoying how a combination of mechanical tactics and broader strategic decisions in a game of incomplete information gave the opportunity for players to scheme execute at levels of complexity far exceeding pro sports or poker. Before this, reading political history was the only other place I could see how incomplete information games played out in real time.

The most satisfying esports scene I’ve ever followed was Starcraft 2 pros circa 2011-3. Youtube and Twitch allowed for a community of expert commentators to grow, and I got in the habit of waking up at 3 am to watch the best in the world play live in South Korea. The mind games of a tight seven-game series where each player had to adjust their strategies to what worked and what didn’t in the prior contests far exceeded the strategic intricacies of an NBA Finals.

After college, video games took a back seat to real life. In China, I’ve started up playing again, justifying gaming by thinking about them as an extension of language practice. On voice-chat playing PUBG paired with random strangers, I try to see how long I can fool people into thinking I’m a Hong Konger with busted Mandarin, or make up a random backstory to use some new vocab I learned.

What drew me back in, however, were these videos of an AI playing against top DOTA 2 players. Here’s a good overview of what’s going on under the hood. Even with inferior mechanics compared to pro players, the AI can compete at the highest level thanks to strategic decision-making and dominant ‘off-meta’ strategies.

These video game AIs can think through first principles in a way more disciplined than any human player. It took the NBA coaches forty years to break from tradition and embrace the fact that three-point shots were a dominant strategy (some still haven’t…), but if some AI were programmed to design plays for humans within the parameters of basketball players’ potential, it could come to this conclusion in a matter of hours. The Google Deep Mind chess AI that has taught itself to beat the best conventional chess programs in the game is cool, but DOTA 2’s level of complexity and constantly shifting ruleset makes Open AI all the more engrossing to watch.

Having put just a few dozen hours into the game, I’m just starting to understand the width of the decision tree and the extent of Open AI’s accomplishment. The game is five on five, so it has team dynamics and specialized roles similar to basketball, except half the time you don’t know where the other team is. With one hundred unique characters and items that you add to your character to respond to what your opponents are doing as the game develops, for each game you have to recalculate what you should be doing at any point in time.

Also, it’s good practice to learn Chinese curse words when I get called out for playing like trash.

YouTube

I try to only watch Chinese tv and movies, but every so often fall down YouTube rabbit holes. The two that have been most interesting have been that of MMA fight analyses and video game breakdowns.

I don’t enjoy watching people get hurt. But channels like The Weasle and BJJ Scout that go into the evolution of fight styles and mind games that comprise high-level fights are hypnotic. I’m looking forward to the day when some AI robot that faces the same physical limitations and has the same damage modeling as a human takes on a UFC champion.

I can also spend hours watching long-form analyses of video games. Games are art (well, sometimes), and, as one of the newest mediums that lives at technology’s cutting edge, are is evolving far more rapidly than books, music or movies. I find it very rewarding following year to year how developers are learning to tell better stories and convey more impactful emotional experiences through video games.

Youtube as a critical medium for video games is a lot better than reading articles since to understand what’s getting talked about; you need to see exactly how the mechanics play out in real time. Thanks to Patreon, we haven’t had to wait for universities to endow chairs of whatever the video game version of “Film Studies” or “Musicology” will be called to get smart people working full-time on accessible quality analysis. I’d recommend checking out Joseph Anderson and Noah Caldwell-Gervais for their literary-inflected criticism, or Mark Brown for his focus on design and mechanics. If you’ve never a video like this before, I’d recommend checking out this episode on the N64 Zelda game Majora's Mask which explores one of the most creative uses of a game mechanic to enhance story-telling.

Next year I want to play more games like Edith Finch that use the medium to its best effect and not just scratch my gaming itch with competitive titles.

Podcasting

For the past year and a half I’ve been making my own show (ChinaEconTalk, an interview-based podcast about Chinese business, tech, and economics). I wrote a bunch of tactical tips here but had two big takeaways from my experience.

The first was how having the pressure of preparing for an interview means you end up learning way more than if you were reading a book for pleasure. The desire to not sound like an idiot in front of my guest and audience pushes me to read much deeper and more attentively than I would otherwise. However, doing this prep with contemporary authors on largely contemporary topics does mean that I lose time from reading more fundamental books (Scholars Stage just put out a great ‘intro to Chinese thought’ reading list) and that I can’t do the Tyler Cowen move of ditching something as soon as it gets boring.

The second was just how many westerners (say 70%) respond to my cold emails. Even before I had an audience to speak of, ‘famous’ people in the China-watching field were happy to come on the show. As for cold-emailing Mainlanders, however, that response rates drops down to 15%. My guess is that it’s a combination of reluctance to speak in English, poorly framed emails on my end, and the greater importance of an introduction here.

Buddhist Repose

When after following his work for ten years my intellectual idol decided to help fund this newsletter, my reaction surprised me. My brain quickly went to “life is suffering, good times will pass, and we’re all going to die.” Yet had I not spent the past year in China feeling very small, I’m confident I wouldn’t have had this reaction.