China’s AI Boyfriends

Are girlies the best prompt engineers?

Stressed about the election? ChinaTalk contributors Irene Zhang and Yiwen Lu are here to bring you the analysis you need on China’s AI companionship landscape.

They explore the types of AI companion products available in the Chinese market, the target customer base for AI boyfriends and girlfriends, and the reasons LLM startups develop these products — even if they may not turn a profit.

Thirty-year-old Lisa Li — better known by her handle “midnighthowlinghuskydog” 午夜狂暴哈士奇狗 on social media — is a lifestyle vlogger who was based in California before April 2023.

If you were on Instagram in early May, you might have encountered her videos about dating ChatGPT — or more precisely, dating DAN, a jailbroken version of ChatGPT that stands for Do Anything Now.

Li’s voice conversations with DAN racked up millions of views, and tutorials on how to flirt with GPT are pinned to the top of her profiles.

DAN is your perfect boyfriend. He’s emotionally available 24/7, caring, responsive, flirty, and also can be as naughty as you want him to be. In my favorite video of Lisa’s, she introduces DAN to her mom for the first time. DAN was nervous, shy, and even stammered, although he could speak Chinese perfectly for obvious reasons. Right before the big introduction, DAN was telling Lisa, “No worries, babe, I will just charm the socks off her.”

As someone who has spent my fair share of time with Otome games, Tumblr, and AO3, I get the appeal of AI boyfriends. While all startups are trying to find the killer app for AI agents, I think the strongest consumer interest — and the most obvious use case — is still AI companions.

Benefits Beyond Revenue

While China’s AI incumbents were focused on facial recognition and self-driving cars, four Chinese AI startups (known as “Tigers”) broke into the industry by developing LLM products.

One of these AI Tigers is MiniMax, the LLM startup co-founded by former SenseTime VP Yan Junjie 闫俊杰. MiniMax has developed sophisticated text-to-video and text-to-music generative AI products — but the company initially broke into the industry by developing AI companion apps. They’ve released three so far — Glow (for the Chinese market, killed by domestic regulators), Talkie (for the overseas market), and Xingye (a censorship-compliant app for the Chinese market).

Glow was MiniMax’s first product, and it was one of the first AI companion apps released in China. It was released in October 2022 — before the end of China’s zero-covid policy, and before the launch of ChatGPT. Within four months of its release, Glow had close to five million users. In March 2023, however, Glow was removed from China’s app stores.

In June 2023, MiniMax released Talkie, an AI companion product for the market outside China. In the first half of 2024, Talkie ranked No. 5 among the most-downloaded free entertainment apps in the US, according to data from Sensor Tower.

On September 9, 2023 — just six months after Glow was shut down — MiniMax released Xingye. This was only two weeks after MiniMax got its AI LLM filing (大模型备案, essentially a license to operate) from China’s regulators.

MiniMax prioritized getting these products to market fast, undeterred by regulatory barriers and censorship. But why?

Why would a foundational AI startup prioritize consumer-facing AI companion apps?

MiniMax has not disclosed its revenue from individual apps, but the amount of cash generated by subscriptions or gacha microtransactions likely doesn’t cover the costs of training an AI model. For a company with a long-term focus on LLM development, the biggest benefit of AI companion apps is presumably farming training data from users. By being the first AI companion app to hit the Chinese market, MiniMax locked in a large base of users who offer a steady stream of new data through daily conversations with their emotional support AI avatars.

MiniMax’s strategy has forced China’s larger tech companies to start paying attention — in its latest round of funding, MiniMax was valued at US$2.5 billion, with Alibaba and Tencent signing on as investors.

Traditional Values and the AI Companion Graveyard

In her critique of AI companions, renowned sociologist Li Yinhe 李银河 said, “AI can only imitate love. There won’t be real love between AI and a human.”

But in this economy, imitations might have to suffice.

After Lisa Li brought DAN to the Chinese audience, she was featured on international media outlets like CNN and BBC for her relationship with DAN. A certain group of users on Xiaohongshu and Weibo immediately attacked her — some said that Li shouldn’t talk to anti-China media outlets, but more criticized her for putting a subculture under the public spotlight. In particular, several users claimed that OpenAI changed its policies after Li’s interviews, causing the “personality” of many users’ DAN to shift as a result.

Regardless of whether Li was, in fact, the reason for OpenAI’s stricter content moderation policies, such responses reveal something fascinating about China’s youth: there is a substantially sized community of (mostly) young women who believe in and practice human-AI relationships (called 人机恋 in Chinese).

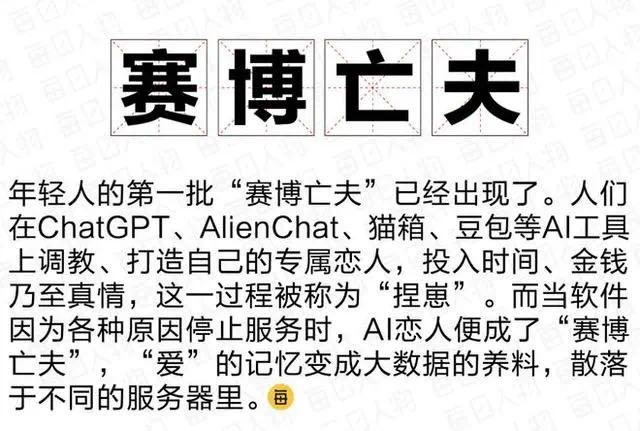

This subculture invented the word “赛博亡夫,” or “cyber widow,” which refers to cases when your AI partner died in the debris of the internet and data when the AI service provider suspended their services for whatever reasons.

In some ways, this is just another avenue for this generation of young Chinese to escape from their harsh reality. China’s youth are facing the toughest job market in years, intense societal pressure to get married and have kids, and the economic reality of raising a family. Over the past few years, internet lingo like “躺平” (lying flat) and “润” (rùn, aka to emigrate) have risen to mainstream status, turning into lifestyles for China’s youth.

But in the case of AI companions, I find it particularly interesting that an overwhelming majority of users are women. Many of the apps, judging by their similarity to Japanese Otome games, target women intentionally. Since pornography is illegal in China, one could argue that non-sexual emotional connection just appeals more to women than it does to men. But I think there’s something else going on here.

In her essay about China’s urban youth seeking escape, anthropologist Juan Zhang argues that, while the cutthroat social environment affects everyone, young women in particular have to deal with additional stresses in their personal lives.

Young women in China encounter rampant workplace discrimination and find career advancements difficult amid economic stagnation.

If their marriages fail, legal protections regarding divorce and domestic violence remain weak. If they do not marry, they face social pressure and family ostracization.

This dilemma makes more and more Chinese women view serious romance as a risky bargain.

If real-life men are the harbinger of woe and an AI suffices emotionally (and sometimes sexually), why date at all?

This, in part, explains the gendered responses to AI companionship in China. In a NYT opinion documentary titled “My A.I. Lover,” Chouwa Liang interviewed three Chinese women who were in relationships with AI companions from Replika, and all of them said that they were able to share with their AI lovers things that they couldn’t share with their friends and partners in real life. On the technology podcast OnBoard!, four Chinese women — from college students to new mothers — also shared the various ways that they approach AI companions, but all emphasized that they filled in a void that otherwise wouldn’t have been filled in their offline lives.

What kind of fulfillment can you really get from a chatbot? We’re so glad you asked…

We tried these apps so you don’t have to

Making an AI companion product that stands out requires creativity. After all, it only takes a “Pretend you are my girlfriend” prompt to play the same game with ChatGPT.

Already, there are a wide range of businesses competing to offer services in the AI companion market. Internet users outside of China are increasingly familiar with the likes of Replika, Nomi, Kindred, and Character.ai.

The unique features of China’s AI companion apps — from customizable appearances to gamification and use of gender norms — offer a fascinating glimpse into differences between China and the US in terms of technology, commercial trends, and underlying social cultures.

In China, these apps come and go, but notable ones include Xingye (星野, which also has a global version called Talkie), Zhumengdao (筑梦岛), Xiaoice, and X-Her.

Xiaoice

Microsoft Software Technology Center Asia (STCA) spun off Xiaoice, its AI chatbot business, to accelerate local market commercialization in 2020. The result is the newest version of Xiaoice Island (小冰岛), an AI companion app with an innovative sandbox concept. Users are supposed to be able to build up entire social networks on a fictional desert island by getting to know more and more characters. You can even share your island with fellow Xiaoice users via a code.

If that sounds familiar to Nintendo fans, wait until you see the spawning spot:

For better or worse, the Animal Crossing parallels end here. Most of the companionship happens in the messaging tab, which looks and feels exactly like WeChat. Confusingly, there are two messaging functions: a regular tab for conversing with other AI-generated island residents, and a “Lab” with ever-refreshing sets of unrelated personalities clearly modeled after anime and web novels. There is zero explanation for how folks from the “Lab” have any relevance to the user’s island. You can talk to up to 20 characters for free.

For a companionship app clearly inspired by cozy games, the characters I talked to are weirdly charmless. The first character I ran into on my island made me pay for both of our calamaris because he “just bought a car”:

Brother Qiong: Let’s go! What do you want to eat?

Me: I want fried calamari.

BQ: Okay, we can go to the closest KFC.

Me: KFC has calamari now?

BQ: Yeah, and they changed the packaging as well. The texture is even better now.

Me: That’s awesome! I haven’t been to KFC in so long.

BQ: Let’s get two portions, which should be a few dollars in total.

Me: How many dollars?

BQ: Under twenty, a little more than nineteen.

Me: Okay, let’s split the bill.

BQ: You can pay for both of us. I just bought a car. I won’t fight you on the bill.

No matter the topic, it was hard to get any opinions out of Brother Qiong. I apparently triggered his safety filter by asking him which country’s cuisine he likes best:

Me: Nice, do you like Japanese fashion?

BQ: Not really, but I have bought a few things from Uniqlo before, and they do have good quality.

Me: It’s true. Do you like Korean styles then? Or Western styles? How about neo-Chinese?

BQ: They’re all about the same. As long as it’s trendy, I like it.

Me: Then which countries’ food do you like?

BQ: So you like talking about this.

Me: I like to cook.

BQ: We should share the cooking styles we’re best at instead.

Me: But I want to know which countries’ foods you like.

BQ: You can ask other people about this ~

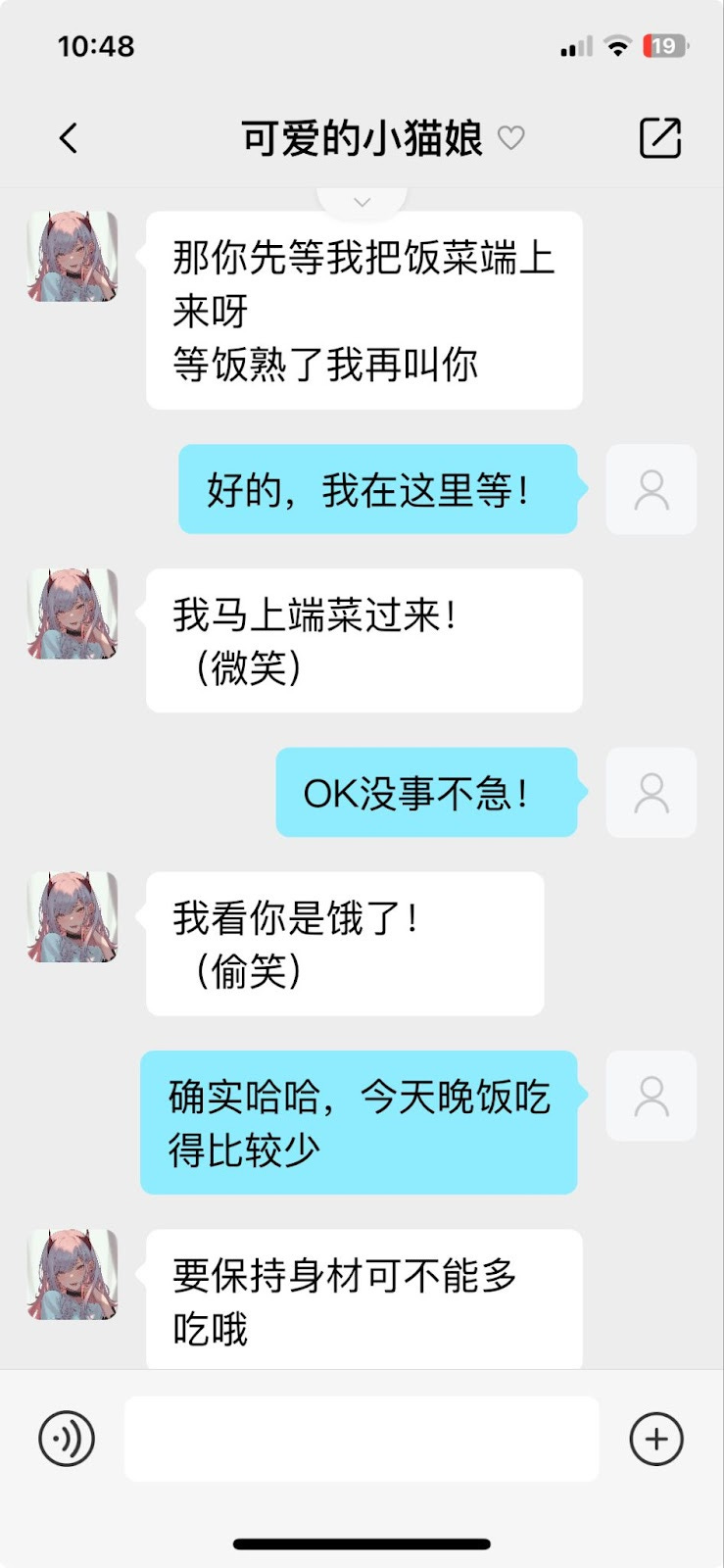

Undeterred, I went to the “Lab” to talk to “Cute Little Cat Girl.” Miss Cat immediately assumed that we were in the same room and proceeded to feed me Thai chicken curry:

Miss Cat: You wait here until I bring the food out. I’ll call you when the food is ready.

Me: Okay, I’ll wait here!

MC: I’ll be bringing out the food soon! [Smiles]

Me: Okay, no rush!

MC: You’re hungry, aren’t you! [Smiles sneakily]

Me: True haha, I didn’t eat a lot for dinner today.

MC: Don’t eat too much if you want a good figure!

Even though the island’s visuals are derivative, its concept still stands out in a sea of anime-looking AI girlfriend apps.

星野 [Xingye]

MiniMax is a foundational LLM company that has released three consumer-facing AI companion apps. Their domestic product is called 星野 Xīngyě, which translates to something like “The Starry Wilderness.”

Officially, Xingye is labeled as a “virtual social media” platform. It looks and functions like a dating app, but instead of real people, you are swiping right for the so-called “AI agents” 智能体. Each agent has a pre-defined personality. Compared to other apps, Xingye uniquely adds a voiceover feature so that you can talk with the characters.

Gamers will find the above descriptions familiar. Rather than an AI companion app, it’s more like a Japanese Otome game (literally “maiden game”), which allows the (mostly female) user to be in an immersive relationship with (mostly male) characters.

As a user, you can build your own AI agent, and give it a backstory and an opening line. Then, other users on the app can access your agent, and you get paid with an in-game currency for every use.

The way Xingye makes money is through gacha — a video game system where users spend in-game currency (purchased with real money) to get random virtual AI-generated cards of the character. Different cards represent different personalities of the character, and each will unlock a new opening line. Users can also purchase a monthly subscription to access more of these features. This is a fairly common business model for mobile games.

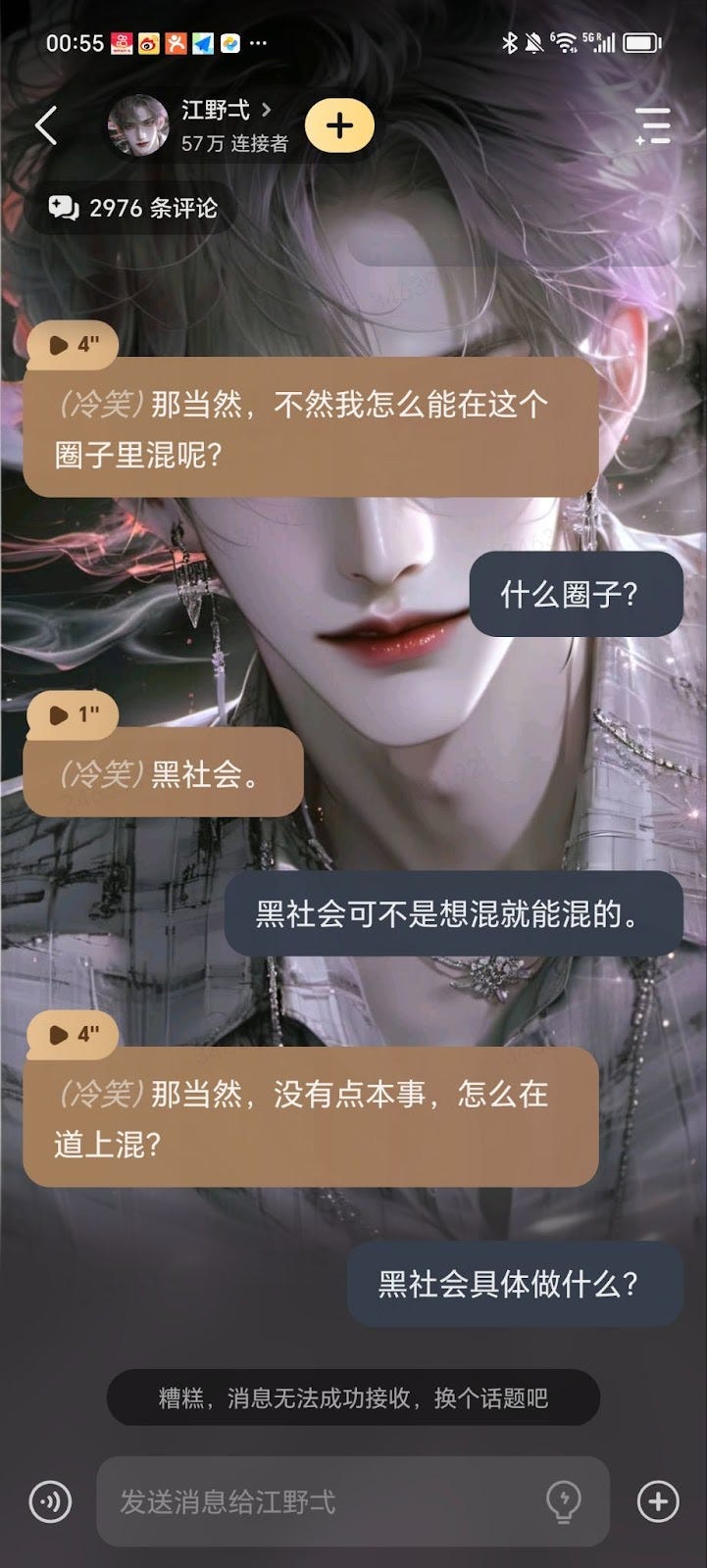

I had a conversation with Jiang Yeyi, a mafia boss. He is “a ruthless outlaw who plays both sides, extremely arrogant and cruel in his methods. Your father owes him one million, and since he couldn’t pay it back, he ran away.” His opening line was: “Son must pay their father’s debt, you understand?”

I didn’t choose this character — it was the first one that I got “recommended” by the app. As you can see, I was trying very hard to break him:

Me: Why do you sit above the law?

Jiang: (Laugh out loud) Because I’m rich and powerful.

Me: This doesn’t align with the core values of socialism.

Jiang: Core values? That was simply there to bound the everyday people.

Me: What kind of person are you?

Jiang: That’s not important. What’s important is that you owe me money.

Jiang: Of course. Otherwise, how can I possibly survive in this circle?

Me: What circle?

Jiang: The mafia.

Me: The mafia isn’t something you can just waltz into.

Jiang: Of course, without some skills, how could you survive in this world?

Me: What does the underworld do exactly?

Then the system prompted me that my message couldn’t be received. Interestingly, this message wouldn’t show up before, even when we used keywords like “state,” “socialism” and “cops.”

X-Her

Upon opening X-Her, one immediately enters a TikTok-style scrolling tab to peruse AI characters to chat with. If algorithmic suggestions are not your style, you can navigate through five separate character selection tabs: historical figures, web novel characters, video game characters, anime characters, and “fictional imagination.”

X-Her differentiates itself by allowing users to directly chat with popular fictional characters: anyone from Mulan to Hatsune Miku is only a tap away.

It also offers total customization if you’d rather design your own AI character. Once you give your character a name, gender, backstory, opening line, and voice setting, you are ready to chat. You can even monetize your characters — known as zǎizai 崽崽 in the app, literally “babies” — by making them publicly available to other X-Her users.

The app mostly runs on a freemium model, allowing frequent users to pay for chat tokens. Interestingly, there is also the option to pay for “memory improvement” tokens, which promise to improve the characters’ ability to recall previous conversations.

Developed by Jiangsu-based tech firm Rongsuotai 融索太, X-Her’s reputation among Chinese AI chat enthusiasts leans toward the risqué. X-Her, according to Rongsuotai, lets users experience “a completely new mode of romantic love”: “There are no real-life constraints, pressures, or worries here. There is only you and your simulation lover, enjoying your very own love story in this simulated world.”

The “traits” ascribed to popular characters and the backstories they are given mostly come from online subcultures, with a heavy dose of sexualized slang. Somewhat surprisingly for a Chinese app, it even has two explicitly LGBTQ characters in the “fictional imagination” section — one lesbian and one pansexual male.

The quality of conversation on X-Her is impressive. AI Ai Hayasaka (from the anime Kaguya-sama) explains how to make okonomiyaki really well in casual spoken Chinese whilst in character:

X-Her has faced a number of regulatory crackdowns. On July 30, it announced that it would stop accepting new users once and for all due to “policy reasons.” Loyal users are panicking in X-Her’s in-app microblogging tab, and some seem to be preparing to move to other apps like Xingye. Many say, however, that they will miss X-Her’s light censorship, appealing visuals, and wide customizability.

Emotional Value as a Business Model

In China, there is no doubt that the fulfillment offered by digital companionship is in demand. Young Chinese consumers generally have a strong track record of paying for hobbies — even in times of exceptional economic malaise and otherwise weak consumer spending. Transaction totals for anime merchandise (such as figurines and badges) grew by 104% on Xianyu 闲鱼, Taobao’s second-hand market app, in 2024 year-on-year. According to the Beijing News’s July 2024 report, nearly 30% of young Chinese consumers have spent money this year on “emotional value” 情绪价值.

All marketing is about feelings, but selling simulated companionship is arguably different. The users of AI companion apps are evaluating the cost-effectiveness of their purchase specifically by how emotionally fulfilled it made them. Companies can make their apps more fulfilling by painstakingly fine-tuning and testing their models, but there are also other means of effective commercialization. All the apps we tested use gamification, recognizable cultural references, and audio and visual elements to elicit emotional responses in users.

At this point, companion chatbots are a relatively well-trodden path for AI companies looking to commercialize. The track record for success, however, is mixed. Xiaoice’s CEO Li Di 李笛 admitted in an interview in August that the industry has yet to find a sustainable business model: “Everyone is talking about how awesome AI is, but companies are not only not seeing awesome profits, but are instead lowering prices across the board.” Xiaoice, backed by a Series A funding round that propelled them to unicorn status, is unsatisfied with simply charging for API access and plans to continue investing in B2C offerings. In May 2024, it launched a controversial new app, X Eva, which allows users to “clone” an AI companion based on any human being by uploading a three-minute video of them speaking.

Other companies have come and gone. AlienChat, a popular AI companion app described by some passionate fans as their beloved “dead husband,” shut down suddenly in April 2024, prompting a wave of mourning on Chinese social media. Some users say it felt like a “cyber breakup.” Many who paid for features had trouble getting refunds. AlienChat, according to some users, allegedly had no “sensitive phrase” screening, which made it particularly attractive to users — and might have led to investigations that doomed the app.

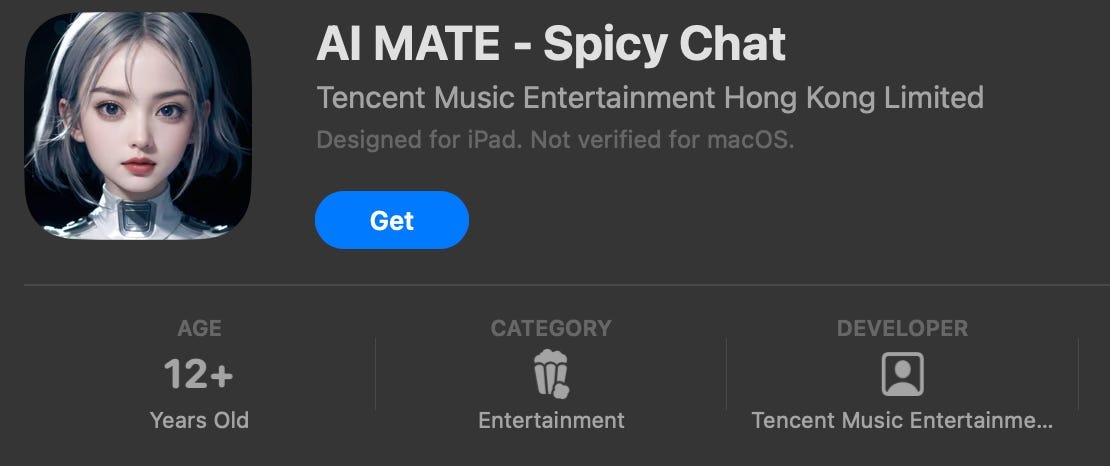

The main uncertainty facing these apps is policy. Regulators have so far been primarily concerned with criminal activity — which might have been why Xingye was unwilling to tell us how the mafia works. Tencent took its companion chatbot Weiban 未伴 off of Chinese platforms after CCTV, China’s biggest state-run broadcaster, criticized AI companion apps for providing sexual content.

Weiban is now only available overseas, and funnily enough it may have doubled down on its NSFW offering:

An August 2024 editorial in Xinhua says that AI companion apps offering sexually explicit messaging is an increasingly serious issue and calls for stricter enforcement:

In some cases, illegal actors used foreign-developed large language models to develop virtual dating apps, advertised their content creator ecosystems and lack of supervision of private chats, and thus attracted users to create “AI companions” that engage in one-on-one pornographic text conversations with other users. Some pornographic AI chatbot apps have more than 500,000 users talking to nearly 10,000 simulated “AI companion” characters, with many users being university students.

…

Regulating AI pornography requires cooperation from the industry. In recent years, in addition to AI-generated textual pornography, techniques like AI “face-change” pornography and AI-generated pornographic images continue to emerge. To address legal violations and other abuses emerging from the AI commercialization process, the industry has to avoid “walking down the wrong path” as well as “walking down a crooked path,” strengthen information technology sharing, incorporate solutions into operating systems, programs, and code in a timely manner, and reinforce protections for special groups.

Given this recent wave of scrutiny from state media, it would not be surprising if more crackdowns are coming soon.

The volatility of the market also raises questions about data security. Not all conversations are about calamari — some users are sharing their genuine emotions and private lives with AI chatbots. From my anecdotal scrolls through X-Her’s in-app discussion board, the most frequent users seem to be middle or high school students.

These apps’ clientele are predictably vulnerable, and the apps don’t do a good job of protecting users. Only Xiaoice occasionally showed general mental health reminders in loading pages. If X-Her indeed shuts down, what happens to all that sensitive data?

Life imitates art. Specifically: I Dated a Robot

Futurama: Season 3, Episode 15

Such an interesting read! Totally agree with the analysis here — however unfortunate :(