The following column I wrote first appeared on TechNode.

Is China pulling ahead of the US in AI? Not quite, argues Dieter Ernst of CIGI in a recent report entitled “Competing in artificial intelligence chips: China’s challenge amid technology war.” His deep dive into the dynamics behind China’s recent progress on AI chips manufacturing merits closer attention.

In addition to the hard engineering, Ernst reveals a social story of a global AI community on the verge of fracture. These new restrictions will likely bring the best out of some Chinese firms, while putting some laggards without the connections to secure government support out to pasture. All the while, basic research is likely to suffer worldwide as ties that bound the Chinese and western academic communities fray.

Most western coverage of western AI firms focuses on those that operate in the application layer of the AI stack. But in order for Bytedance to instantly recommend tailored TikTok videos, or for JD to optimize delivery orders, they need to run their applications on increasingly specialized and sophisticated hardware.

What AI chips do is optimize performance for specific tasks further down the AI stack. For instance, an AI chip can be tailored specifically for facial recognition, autonomous driving, or cloud computing. The best of these chips represent the bleeding edge of global semiconductor technology and have grabbed the attention of Washington and Beijing. The Trump administration sees Chinese semiconductor progress as a grave economic and national security threat and hopes to use a combination of sanctions and incentives to slow down China’s work on AI chips. Beijing officials hope to create a self-sufficient industry capable of withstanding American sanctions and ultimately competing on the world stage.

Basic research lies at the heart of AI development. American researchers invented the field, and have been at its forefront ever since. Ernst contends that America’s “informal, flexible, and undogmatic approach to innovation is, arguably, the root cause for the resilience of the United States’ AI development trajectory.” He argues that “technology diffusion through knowledge networks, combined with intense contests among competing ideas” throughout academia, DARPA projects, and the private sector have made the American AI and semiconductor ecosystem the world’s most vibrant.

In contrast, China has struggled to marry basic research with industry.

China’s electrical engineering community was practically wiped out by the Cultural Revolution, forcing researchers in the 80s to start decades behind global best practices. It has to contend with severe disconnects between academia and industry as well as, Ernst writes, “the institutional heritage of the Soviet planning system” that framed enterprises’ work to meet production targets and not conduct research themselves. The research was instead reserved for national institutes and the like.

Until recently, the commercial and academic Chinese AI communities rarely interacted. While two of Ernst’s contacts in Chinese consumer-oriented AI companies noted that they had some researchers from public organizations take on moonlight consulting work, these sorts of arrangements pale in comparison to the public-private revolving door ecosystem America has created.

Many western analysts have pointed to China’s share of global AI publications as evidence of increasingly successful basic research efforts. The global AI research community is notable for its openness, with academics commonly posting their research in open platforms like Github and arXiv online. “If you don’t share your work, it’s meaningless,” Yunji Chen, a researcher at the Institute of Computing Technology in Beijing, emphasized in a 2019 interview with Nature.

The global AI research community is, by and large, not happy about politics intruding.

A Huawei researcher who due to a US State Department travel ban was forced to deliver his presentation remotely received a rousing round of applause at a normally staid conference.

But politics is already reshaping the academic community. As Western universities reject Huawei’s and iFlyTek’s money while facing increasing scrutiny for connections with the Chinese government’s Thousand Talents plan, western researchers are forced to reconsider their Chinese connections. Co-authorships develop out of connections made through global conferences and academic fellowships, which are less and less likely to be accessible to Chinese nationals.

I’d be interested to see research that asks whether the global community is splitting into Chinese and western halves—perhaps measured by how often researchers on each side of the divide co-author with the other? This disconnect is likely to harm upstart Chinese researchers more than established western ones, while undoubtedly slowing overall progress in the space.

This development comes at a time when basic research is only growing more important in the field. As AI chips are called upon to process massive datasets, companies around the world need to innovate with new architectures. This “paradigm shift” as “the focus of semiconductor innovation shifts from process technology and fabrication to architecture and design at the front end, and post-fabrication packaging at the back end” leaves an opening for Chinese upstarts to contend with American giants like Intel, AMD, and NVIDIA.

But despite the PR bluster, Chinese firms are all to various degrees behind the cutting edge and vulnerable to American actions. Chinese AI chip startups mostly focus on inference, as opposed to training algorithms, a much less technically demanding task. The fact that American capital markets are seemingly closed off to Chinese AI firms is another significant hurdle. While regulators are working on carveouts for tech firms, for the time being going public on Chinese stock markets requires three years of profitability, a rule that discourages investment in R&D.

Industry experts agree that China only really has one player capable of competing with American giants on an even footing in any AI chip vertical: Huawei’s HiSilicon. And even HiSilicon is severely vulnerable to US sanctions. Since its most advanced chips are manufactured in Taiwan at TSMC’s 7nm foundries, American pressure could force Huawei to cut ties with one of its most important AI chip partners. As this past week’s Department of Commerce regulation release attests, it looks like the US is preparing to drop this hammer. Given that Huawei has been preparing for years for the US government to come after it, the fact that they still have foreign parts in their flagship phones means that this is much easier said than done.

American firms also stand to lose out from increasing restrictions on their ability to sell to Chinese companies. “A staggering 67% of Qualcomm’s revenue comes from China, for Micron this is 57%, and for Broadcom 49%.” With nearly one-fifth of US semiconductor firms’ revenue reinvested into R&D, any big hit to their top line, if not paired with substantial US industrial policy to make up for this gap, will have long term consequences for US competitiveness relative to Chinese, European, and other Asian competitors.

Chinese companies have made some real progress, particularly in areas where China has a natural comparative advantage. For instance, China currently leads the world in a handful of narrowly defined AI chips related to surveillance. Further, some argue that China has an edge in access to cheap, structured data sources thanks to a large pool of affordable college-educated labor. However, data-labeling is eminently outsourceable, and nowadays Chinese labor really isn’t cheaper than comparably educated Indians or Filipinos. After all, average hourly rates on Mechanical Turk are just $2 and a global pandemic forcing people to stay at home is sure to increase supply in the west as well as in China.

American sanctions are forcing Chinese players out of their comfort zone in ways that will help the ecosystem over the long term. As anonymous blogger Youshu writes,

Some will no doubt say that “Yeah, we knew China wanted to develop its own semi industry, so what’s the rumpus?” This observation misses the mark. Before private firms were happy with the Americans, and state firms would just tell their bosses there were no good alternatives. But now orders are being pushed towards domestic rivals, even where they are not very good, providing them with revenues today, and confidence about future revenues, with which to fund R&D.

Ernst is more pessimistic. He expects “islands of technological excellence [to] continue to coexist with deeply entrenched structural weaknesses in China’s emerging AI chip industry.” The Chinese AI industry will doubtless continue developing but in my view is unlikely to challenge America for global preeminence any time soon.

Columns like this take a lot more work than translations. If you like them do let me know by responding to this email!

Also, please consider donating to my Patreon.

Chinese/Italian Painter of the Week

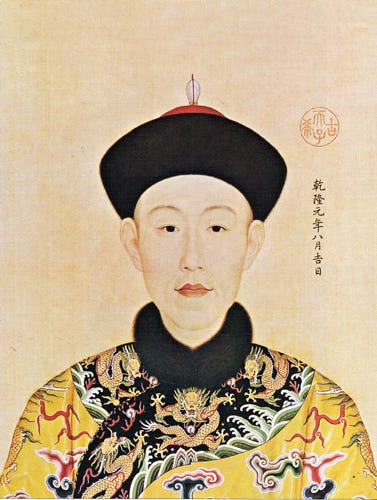

Giuseppe Castiglione, aka Lang Shining (郎世寧), was born in Italy in the late 1600s. A Jesuit painter, at 27 he packed his bags for China and started to make waves in Emperor Kangxi’s court. From a contemporary Jesuit record of his life,

Once in the city, the Emperor ordered Castiglione to be conveyed to himeven before he had met our people [the Jesuit missionaries]. Without pre-amble the Emperor asked Castiglione to paint a bird. Castiglione obeyed and he did it so skillfully that the Emperor was wondering whether the bird was alive or painted.

His paintings use traditional Chinese landscape materials and techniques but also incorporate western Renaissance innovations like shading, perspective, and lighting. This is ridiculously difficult as unlike with oil on canvas, you don’t get second chances with watercolor or tempera and silk.

He was sensitive to his audience though. Says Wikipedia, “strong shadows used in chiaroscuro techniques were unacceptable in portraiture as the Qianlong Emperor thought that shadows looked like dirt, therefore when Castiglione painted the Emperor, the intensity of the light was reduced so that there was no shadow on the face, and the features were distinct.”

Although for most of his career he saw fit to “shut up and paint,” he was on at least one occasion able to successfully intercede on behalf of his persecuted Jesuit brethren. From an article in Pacific Rim Report,

On two (possibly three) occasions of which I am aware—one was certainly in 1736 and another is documented a decade later in 1746—he broke all rules of court etiquette by appearing too distressed to paint when Qianlong arrived at his studio. The concerned ruler asked what was the matter and to the horror of the emperor’s retinue, Lang Shining threw himself on the floor and begged the emperor to intervene on his order’s behalf during a spate of renewed persecution.

The first time he did this, Castiglione got his wish from Qianlong, and the harassment of his cohorts stopped. But the second time, in 1746, was to no avail. Lang Shining’s plea for imperial intervention to save the life of a fellow Jesuit was firmly rebuffed. Qianlong said coldly to him at the time: “You Europeans are foreigners. You do not know our manners and customs. I have appointed . . . grandees . . . to take care of you in these circumstances.”

Not long after that pronouncement, during a lighthearted debate between Castiglione and Qianlong’s retainers about the merits of Christianity during another painting session, Qianlong impatiently interrupted and said angrily to the Jesuit, “画吧” or simply, “PAINT”—“Get on with your painting!”

This life likely got old for poor Guiseppe. As one of his colleagues wrote, in a sentiment echoing centuries of Western frustrations working in China,

“Will this farce never come to an end? . . . I find it hard to convince myself that all this is to the greater glory of God . . . to be on a chain from one sun to the next, barely to have Sundays or feast days to pray to God; to paint almost nothing in keeping with one’s own taste or spirit; to have to put up with thousands of other harassments . . . all this would make me return to Europe if I did not believe my brush was useful for the good of religion, and a means of making the emperor favorable toward the missionaries who preach it. This is the sole attraction that keeps me here, as well as the other Europeans in the emperor’s service.”

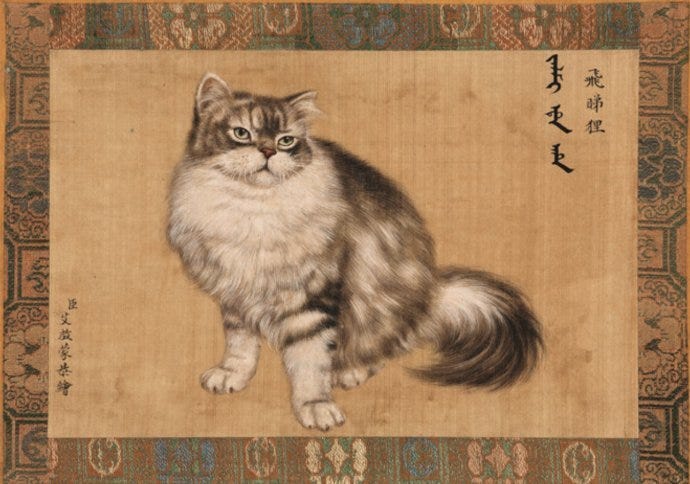

Below are some more paintings. I quite like his animals but it just feels off. Spending lots of time with traditional Chinese painters gives you a bit of a sense of how mind-blowing his techniques must have been in the high Qing. Even today his figures feel out of place with the backgrounds, like some painting algorithm that isn’t quite there yet.

The sheep are great though.

DaShan played him in a 2005 CCTV drama which is just too perfect.