China's Myanmar Quagmire

The Myanmar coup leaves China with no good options. It’s a complete disaster for its Belt and Road dreams and Sino-Burmese relations, but any attempt to oppose the coup is fraught with peril.

Brian Wong, the Founding Editor-in-Chief of the Oxford Political Review and a Rhodes Scholar from Hong Kong, authored the following piece.

The February 1 coup in Myanmar has left the country reeling from some of the worst violence witnessed in recent political history. The military (Tatmadaw)-mounted thwarting of the National League for Democracy (NLD)-led democracy plunged Myanmar into a power vacuum. Neither the army nor the anti-coup protesters have managed to win the upper hand. Whilst the army retains nominal control of the country’s government and political apparatus, as well as large swathes of its economy and media, the defiant civil society – under the fragmented leadership by disparate actors such as the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) and the General Strike Committee of Nationalities (GSCN) – holds substantial sway in highly populated urban regions and regions where the NLD has traditionally enjoyed substantial support (including the former capital Yangon and the second-largest city, Mandalay).

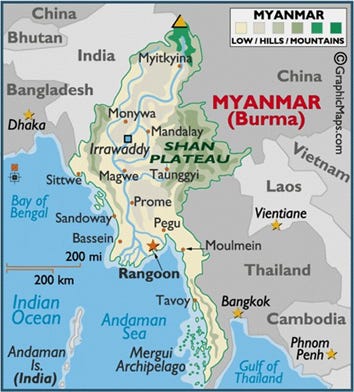

Myanmar and China share a 2,129km-long border.

Amidst all this, China has come under attack from both the international community and the movement on the ground for its ostensible support and backing of the coup. Chinese diplomats have – ignominiously – refused to explicitly take a stance against the Tatmadaw, terming the coup a “major cabinet reshuffle”. Despite its ambassador to Myanmar openly declaring that the coup was “absolutely not what China wants to see”, its critics remain unconvinced. Chinese firms and locals have been targeted by protesters, who are adamant that China’s reluctance to take a stance is both a sign of and complicit in its tacitly condoning the Tatmadaw’s actions.

The Myanmar coup leaves China with no good options. It’s a complete disaster for its Belt and Road dreams and Sino-Burmese relations, but any attempt to oppose the coup is fraught with peril.

The Coup Was Not in Beijing’s Economic Interests

Firstly, the army is substantially less reliable a partner than Suu Kyi’s NLD regime. The army has repeatedly flip-flopped on critical infrastructural projects, including the Myitsone Dam, which was a $3.6 billion mega-dam project shelved by former President Thein Sein, the previous military leader that had overseen the country’s partial democratization and liberalization. China has persistently viewed the Tatmadaw’s expansionism and hyper-nationalistic militarism with suspicion.

In contrast, the ousted Suu Kyi’s NLD government has historically proven to be a substantially more reliable trading and economic partner. The NLD courted the support of more internationalist elements within the Tatmadaw, and through their conjoined efforts, as well as the opening-up to private capital and foreign investment in the country, bilateral trade between China and Myanmar surged substantially. China had occupied little over 6% of Myanmar’s total export volume – a figure that would later increase to 33% in 2019. Suu Kyi has herself repeatedly advocated the pursuit of friendly relations with China in the interest of Myanmar’s economic development.

Furthermore, China has received substantial backlash for, in the minds of many Burmese, backing the coup. Chinese-financed factories were set ablaze, with Chinese staff injured and trapped by attacks on garment factories in Hlaingthaya. China’s calls for “further effective measures to stop all acts of violence” have been met with vitriolic dissent and threats of further violence by internet users in Myanmar. Relations between ethnic Chinese communities and the local Bamar majority – fraught even under the best of times – have deteriorated substantially, with prominent local and foreign investors considering withdrawing from joint Sino-Burmese projects.

China has clear skin in the game. The Sino-Myanmar oil and gas pipelines – an integral component of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) – have come under substantial public scrutiny, after a February 23 meeting in which Chinese officials sought reassurances from Tatmadaw that the pipelines would be defended with heightened security. Elsewhere, protesters have declared that an attack on China’s pipelines would be an “internal affair”, as a sardonic snipe at the rationale China has given for not intervening in Myanmar’s “domestic politics”.

Workers at the site of Chinese-funded project

Diplomats under Xi had long viewed the economic successes of the Sino-Burmese relationship as a pivotal proof of concept for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as well as a testament to a renewed model of diplomacy that would cut across conventional ideological fault-lines. Economic benefits from leading Chinese ventures in Myanmar, such as the banana trade, the Myitkyina economic zone in the Kachin state, and the ongoing expansion in transportation infrastructure in Northern Shan state, had long been touted by China as a demonstration of the political returns and economic rewards of collaborating with the country.

The coup and ensuing unrest have are upending China’s plans. While staunch, pro-China allies in the region (e.g. Cambodia and Laos) would find themselves largely convinced – whether it be through manipulation or genuine conviction – of China’s merits as a partner, others are both visibly alarmed by China’s reticence to oppose the coup and the potential spill-over implications of the crisis. Indeed, China faces a greater headache ahead – the prospects of heightened American military or indirect presence in the region. None of this is in Beijing’s economic or, indeed, geopolitical interests.

China’s Dilemma – Caught in a Bind

It is one thing to argue that the coup did not benefit China. It is another to assert that China would be distinctly and apparently benefited by seeking to end the coup. In truth, China is caught in a bind. On one hand is the plethora of reasons – outlined above – for which it should not back the Tatmadaw. On the other hand, China is wary of its other geopolitical commitments within the region.

Firstly, Beijing is wary of coming across as wavering or indecisive in its commitment to backing other strong-man regimes in the region. The CCP views the Milk Tea alliance with wariness and suspicion, especially in light of the increasing salience the movement is attracting in international media. Should its diplomats vocally and unambiguously oppose the coup, the move could well alienate other strong-man regimes in Southeast Asia, with which China has continually sought to cultivate long-lasting partnerships.

Secondly, should Beijing seek to intervene visibly in Myanmar in favor of the protest movement, not only would this pose a justificatory challenge for its policymakers, but it would also open the floodgates to similar questions being asked of its ongoing support for authoritarian regimes in Cambodia, Laos, and flawed democratic regimes in Thailand and Bangladesh. Politics comes from the barrel of a gun – and the guns of these countries would only be aimed away from China provided that Beijing leaves their political arrangements intact.

Thirdly, whilst China is wary of increased Western presence in the region (as forecast and demanded by the ongoing calls for humanitarian intervention from the United Nations and the West), it is equally wary of committing itself to a protracted military conflict right to the south of its border. When push comes to shove, what matters is less who wins in the ongoing tussle for power, and more when this tussle concludes – its primary interest lies with conflict termination, as opposed to conflict mediation. It has limited incentive to throw its weight behind a movement with elements that have openly decried its presence and involvement in the region.

Hence China is caught between a hard place and a rock. Beijing may not like the Tatmadaw generals very much, but they must, or so it seems, put up with the guns – at least for now.

So What’s Next for China?

China’s hands are tied. It is highly unlikely that the Chinese government would consider sending in troops to force the Tatmadaw to step down. Such a move would be logistically infeasible, economically costly, and optically disastrous for China as it seeks to maintain its image as a non-interventionist power. The sheer improbability of this option, however, also effectively annuls the credibility of any threat of force – which removes a possible tool from China’s arsenal in mediating or pressing for a resolution to the conflict.

China could also sit by and await the crisis’ denouement, though in doing so it could be committing – inadvertently – to substantially greater risks. Myanmar’s economy is slipping dangerously close to the edge of collapse, and it remains unclear if the protests would indeed subside under the ineffective, albeit brutal crackdown from the Tatmadaw. Beijing would be grossly mistaken to think that the protests would subside – even with military enforcements and, as the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar described it, “effective measures to stop violence and punish perpetrators” (essentially translates to, the usage of force by local police and army against protesters). If this were to happen, the haranguing of Chinese businesses and civilians would only escalate in the short to medium run. There is no exit path for China unless it can clearly and explicitly disentangle itself from the Tatmadaw’s ruinous reputation.

A temperate, middle path does lie ahead. Beijing should work with ASEAN states and the United Nations in pressing for the release of political prisoners and convening of unfettered, open elections within six months. China should also lay down the law in condemning and insisting that the Burmese military refrain from deploying violence against civilians – this need not come at the expense of its infrastructural projects, which can be defended with targeted security deployments. Finally, mediation and brokering a ceasefire as well as a temporary power-sharing arrangement could be alternative pathways Beijing can and should consider. This path strikes the balance between the two extremities – for both Beijing and Myanmar at large.

How China in fact acts will depend upon a multitude of factors. Firstly, there exist substantial divergences amongst diplomats and army in China – with competing factions jostling for control and verdict over the country’s overarching Myanmar policy. The Chinese army is no fan of the Tatmadaw – the PLA had historically backed rebel groups and ethnic minorities at the fringes of the Burmese state, with the intention of containing the irredentist tendencies of its counterpart. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) on the other hand, views the Burmese situation more through the lenses of another potential proxy conflict between China and the West: to capitulate or give in to international humanitarian pressures, would constitute a symbolic defeat in China’s ongoing rebuking of the Western model. This, of course, does not imply that the MFA are by any measure fans of the Tatmadaw. How these intra-governmental disputes play out – especially given the already-stretched resources of the Foreign Ministry in light of the recent high-level talks at Anchorage and fraying US-China relations – remains to be seen.

Secondly, will ASEAN states extend the olive branch to China, in enabling the country to play a role in crafting a regional consensus over Myanmar? China is unlikely to undertake the initiative of demanding genuinely accountable elections and return to civilian governance, on its own – after all, the Tatmadaw offers Beijing greater certainty (in theory) than a Milk Tea-alliance-infused opposition front. Only when ASEAN states come out in favor of China’s regional presence, and in acknowledging Beijing’s interest in Myanmar, would China be open to collaborating with the regional bloc over the evolving crisis.

Finally, how staunchly China comes out in favor of either side will depend heavily upon the extent to which it perceives its optics and reception in Myanmar to be salvageable. Should it read its winning the hearts and minds of the Burmese public as a lost cause, then China could well, all things considered, support an ambitious, expansionist semi-enemy, over what it perceives to be a Sinophobic people.

In any case, the resolution of the crisis raging on in Myanmar is unlikely to come any time soon. China’s response to the crisis could well offer a preview of its new approach to regional diplomacy under a new White House administration.