China's New AI Plan

And how it compares to Trump’s

The world’s two greatest superpowers released action plans for AI only 34 days apart. Back in July, the Trump Administration released America’s AI Action Plan to cautious fanfare. And on August 28, China’s State Council published its “Opinion on In-Depth Implementation of the ‘Artificial Intelligence +’ Initiative” (关于深入实施“人工智能+”行动的意见, hereafter abbreviated to “AI+ Plan”).

The two documents both come from the highest echelons of government in their respective countries, and both are high-level roadmaps issued as guidance for departments and ministries to implement. The grounds they cover and the policy intentions behind the measures give us the clearest pictures yet of how these two governments are making sense of the future of AI in their respective countries and around the world. Comparing how the two documents address overlapping issues is an instructive and incredibly revealing exercise. Below is an executive summary of similarities and differences.

Note: Side-by-side comparisons of the Chinese original and English translation were created in Claude, with thanks to Matt Sheehan!

Origins, leadership, and competing priorities

The US AI Action Plan was a product of Executive Order 14179, one of the many flurries of EOs signed during President Trump’s first few days in office, and was jointly led by the White House Office for Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), Trump’s AI Czar David Sacks, and the National Security Advisor (NSA).

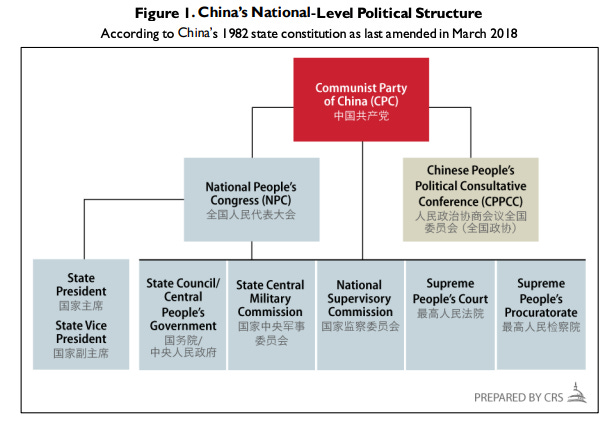

The Chinese plan, on the other hand, is a directive straight from the State Council, with no additional credits to specialized ministries. The final paragraph tasks the National Development and Reform Commission with coordination rather than any specific policy portfolio. This means it was a comprehensive effort by China’s highest state administrative organ. The State Council is technically the organ that executes decisions by the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s unicameral legislature. As is expected in an autocracy, NPC delegates have little actual leverage. Instead, the State Council is better understood as the supreme coordinating body for the country’s 26 ministries and 31 province-level governments, only one step below the Communist Party’s Politburo. As illustrated by the Congressional Research Service’s org chart for the CCP:

A huge variety of input from all corners of the Chinese bureaucracy likely went into the Chinese AI plan. And it shows: the document is comprehensive to the point of being overstretched, covering AI’s coming role in everything from industrial R&D to “methods in philosophical research.”

China’s campaign-style governance makes it easy to engage a policy aim as a whole-of-society effort. A document like this is meant to be distributed widely to ever-lower levels of government and “studied” by ambitious bureaucrats across the nation. Its words will be picked apart carefully in the provinces to divine policy directions that Beijing will find favorable. The US AI Action Plan will not have the same level of buy-in from fellow bureaucrats across Washington and beyond — perhaps especially now, at an unprecedented political moment for the federal civil service. Indeed, it is a list of recommendations that will see extensive negotiation with stakeholders in other agencies and levels of government who don’t necessarily share similar views.

This doesn’t mean the Chinese one is likely to be more successful; indeed, the American plan goes into much more detail on exactly which bureaucratic processes to work through in order to achieve its goals. China’s political campaigns have led to as many successes as it has disasters, with the most recent being Zero Covid. It will be fascinating to see which side makes faster progress in the long term.

Framing, goals, and techno-optimism/accelerationism

The Chinese AI plan is as techno-optimistic a document as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) might produce at this moment. One might even call it accelerationist: except for a single line item discussing AI safety risks at the very end, practically all other sections of this document call for further development and incorporation of AI across society, with guardrails and ethics relegated to complementary positions. Zhou Hui 周辉, an AI governance expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Institute of Law who participated in the document’s drafting, said in a September 8 interview that consensus throughout the drafting process was that “a lack of development would be the biggest safety risk” (不发展才是最大的不安全).

Specifically, Chinese accelerationism-as-policy focuses on expansive experimentations with industrial and social applications, rather than abstract visions of “AGI”. There is a sense of urgency underpinning the document, especially at the beginning when it sets out numerical targets: 70% of the country will have adopted AI-powered terminals, devices, and agents by 2027, and by 2030 the adoption rate will reach 90%. The document elevates the “intelligent economy” to the status of a pillar of “achieving basic realization of socialist modernity by 2035” (到2035年基本实现社会主义现代化), which is the overarching national goal enshrined during the 19th Congress of the CCP in 2017. To be clear, there are no objective metrics against which these goals’ realization can be measured, making them more symbolic than rigorous. However, these numerical targets will incentivize bureaucrats across ministries, provinces, and technologically strong cities to create policy programs that demonstrate their commitment to such ambitious goals.

Much has already been made about the pro-development bend of the US AI Action Plan, which opens with cutting what’s framed as Biden’s red tape. The tech race with China informs the US Plan’s views about speed of innovation more than arguably any other issue: it is suffused with language referencing “domination” and the political necessity for America to have “the best” AI systems in the world. The Chinese document, by contrast, seems to posit China against itself. Another consequence of there being apparent whole-of-government input is that geopolitical implications, primarily the domain of the foreign and state security ministries, are not explicitly top-of-mind. Notably, unlike the US plan, the Chinese AI+ plan does not mention defense or the military whatsoever. The goal, instead, is very abstract:

“Reshape the paradigm of human production and life” is a subtle attempt at connecting AI policy to the PRC’s Marxist-Leninist ideological underpinnings; eventually, it seems to imply, AI integration might lead China closer to the realization of full economic revolution under communism. This is, of course, theoretical to the point of being slightly irrelevant. That being said, it signals that the primary aim of China’s AI+ Plan is to leverage AI to achieve transformations in China’s economic society, and not necessarily to shape the balance of power between Beijing and Washington. This is not to say that the PLA has no plans to make use of AI, or that the Chinese foreign ministry isn’t analyzing the US-China tech race; the truth is almost certainly the opposite. But from what the Chinese state is choosing to communicate publicly about its vision for AI, we largely see a strategy framed around domestic socioeconomic governance.

Open source as strategic imperative

Both Chinese and American leaders explicitly see leadership in open source as a strategic asset. The Chinese document calls for building up open source technological frameworks and social ecosystems that are “open to the world” and creating projects and developer tools with “international influence.”

To do so, the government will give academic awards to students, researchers, and lecturers who contribute to open source projects, as well as create incentives for both public and private sectors to explore and develop open source applications. More holistically, the document encourages open-source access as part of a push to make AI access global. This is the lesson Beijing took from the DeepSeek moment: China’s current advantage in AI lies in having an open source community that empowers robust exchanges and rapid iteration.

The US plan betrays anxiety stemming from the same shock, asserting that “[we] need to ensure America has leading open models founded on American values.” Similar to the Chinese plan’s geopolitical undertone, it calls the value of open source models “geostrategic.” For the US government, the bottleneck preventing more good open source models from being developed that it is best-placed to address appears to be researchers’ access to compute clusters. The American plan’s recommended actions mostly focuses on making it easier for academia and startups to access resources through NAIRR:

Diffusion and job market impacts

The US AI Action Plan calls for many more Americans to be employed as electricians and HVAC technicians so as to serve a bigger buildout of AI infrastructure while creating high-earning blue-collar jobs. It creates a detailed roadmap for how the federal government can leverage its bureaucracy to train more skilled workers in these domains. It describes itself as a “worker-first AI agenda” and seeks to fund more retraining for workers impacted by AI-driven redundancy. However, its assessment of the impacts AI might have on the labor force appears relatively optimistic: it merely calls on the Bureau of Labor Statistics to study AI’s impacts on the workforce through analyzing already-existing data, rather than collecting new data or establishing preventative policy measures.

For Beijing as well as Washington, job displacement might be worth it if AI adoption leads to stronger economic growth. China’s plan, however, is more aggressive about the literal replacement of human labor. Tertiary industries are the fastest-growing employment sector in China, as the services sector increasingly competes with traditional manufacturing; gig work, from ride hailing and delivery to even some factory work, is rapidly expanding to soak up excess labor supply. But this is how the document addresses how AI shall shape the services industry:

“Accelerate the service industry’s shift from digitally empowered internet services to new, intelligence-driven service models … Explore new models that combine unmanned (automated) services with human-provided services. In sectors such as software, information services, finance, business services, legal services, transportation, logistics, and commerce, promote the wide application of next-generation intelligent terminals/devices and intelligent agents (AI agents).”

Elsewhere in the document, the State Council does bring up impacts on employment. It instructs regulators and industry to “[strengthen] employment-risk assessments for AI applications; steer innovation resources toward areas with high job-creation potential; and reduce the impact on employment.” But such a statement is weak without explicit instructions to ministries or regional governments to secure employment. In places like Wuhan where robotaxis have already displaced traditional jobs, the government has no meaningful template of action. The post-Reform Chinese state has previously made explicit policy decisions to sacrifice employment, and consequently the danwei-based social safety net, for what it saw as necessary economic restructuring. Between 1995 and 2001, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) laid off 34 million workers — a third of all employees in SOEs — in an effort to reform the state sector. The layoffs devastated vast industrial regions and led to major unrest, but Beijing persisted on course. More recently, the impact on jobs was completely disregarded to prevent infection during the Covid-19 pandemic. Today’s China has no activist labor movement, no independent unions, and limited protections for workers’ rights. This document, produced during an already-ongoing unemployment crisis that heavily affects young workers, opens up the possibility that the state may be once again willing to put workers aside for national strategic aims.

The plan imagines adoption, application, and diffusion of AI as a whole-of-society effort. Beijing wants AI applied to everything from philosophical inquiries to residential construction standards:

It calls for coordination between AI and other emerging technologies, including biotechnology, quantum computing, and 6G telecommunications. Part 2 of the document, focused on actions to take, dedicates a whole section to consumer-oriented upgrades: it mentions not only well-known fields like wearables, electric vehicles, drones, and brain-computer interfaces, but also more quotidian areas of potential AI applications like travel, e-commerce, and “emotional consumption.” These lines subtly indicate to aspiring entrepreneurs that the government is shining a green light on consumer product innovation and so crackdowns are unlikely in the near future. Beijing seems unconcerned about an AI bubble or over-proliferation of wrappers; indeed, it’s actively encouraging experimentation and calling for “trial-and-error and mistake-tolerant governing systems” for AI adoption. That means that no, Chinese AI adoption will not be dramatically hampered by worries a model occasionally says something impolitic.

The US AI Action Plan’s section on adoption calls on American industry to adopt a “try-first” culture. The Trump Administration seeks to diffuse distrust of emerging technologies and create frameworks within which critical sectors can experiment with AI safely. The specific measures the US AI Plan suggests, however, look more cautious and grounded than to its Chinese counterpart:

Whereas the Chinese document wants all sectors in society to try AI first and get results after, the Trump administration seems to be gesturing towards a more careful path forward with quantifiable findings and measurable improvements. We won’t know which one of these approaches is better until after the fact; in fact, each might have its advantages depending on the sector it is being applied to. But on this point, the divergence between these two documents is dramatic.

International risk governance

The US wants to export its “full AI stack” — hardware, models, applications, and standards — to allies, and allies only. Washington’s vision of international AI governance divides the world between American and Chinese spheres of technological influence and seeks to make the former bigger. Its language on how to counter Chinese influence in international governance organizations is characteristically Trump-Administration, with mentions of “cultural agendas” and “American values,” but its focus lies with overall deregulation.

As usual, the Chinese plan is framed around the United Nations as the primary mechanism for international governance. It wants to improve AI access for the Global South and doesn’t explicitly require these countries to support Chinese values. Of course, this doesn’t mean the Chinese government is completely uninterested in ideology; as recently as June this year, a state media op-ed republished by Xinhua emphasized the risks generative AI posed to “social trust systems and the ideological safety line.” But from the perspectives of listeners in Global South capitals, judging by these two documents alone, China’s offer likely comes off as more value-neutral on the surface.

More Notes!

The two documents address many similar issues under the AI governance umbrella, but also diverge in terms of topic selection. Some items that fell outside the Venn Diagram overlap:

The US AI Action Plan’s understanding of cybersecurity is far more mature than its Chinese equivalent. It addresses adversarial threats, vulnerability-sharing frameworks, and incident response with attention to both government and private-sector shareholders. As part of its understanding of AI as a race, the US document is much more sober about the cyber risks around AI models. By contrast, cybersecurity is almost entirely missing from the Chinese plan. This may partly be because the Chinese document avoids defence in general, but even in sections addressing government and private-sector adoption, very little energy was spent on considering how to secure the process.

Congruent with Beijing’s now-longstanding focus on data as a factor of production, the Chinese plan dedicates far more space to harnessing the economic potential of training data. The State Council argues that China has a “data-rich advantage” in AI. It wants innovative measures to increase data supply, including by bolstering the data processing and data labelling industries. (It’s worth noting that data services can create relatively low-barrier jobs in underdeveloped parts of China, which might contribute to Beijing’s enthusiasm.) That being said, both countries’ plans pay particular attention to scientific datasets. The US AI Action Plan recommends measures to create “world-class datasets” by setting data standards and making federal datasets more accessible to researchers. The Chinese one, similarly, seeks to accelerate scientific discovery by “[building] open and shared high-quality scientific datasets and [improving] the ability to process complex multimodal scientific data.”

ChinaTalk previously covered how AI is shaping education in China. In the State Council’s AI+ Plan, education also receives substantial attention. Not only does Beijing want more incorporation of AI tools into the education system, it also wants to bridge technological promotion into eventually “[promoting] a shift in education from focusing mainly on knowledge transmission to focusing on ability improvement”. This is an especially ambitious goal in China’s education system, where exams and rote learning are still king. Will AI be the thing that finally transforms the Gaokao?

“National security” appears 24 times in the US AI Action Plan. The US government sees basically every part of the AI ecosystem, from manufacturing to software exports and international governance, as critical to its future conception of national security. The Chinese one, by contrast, only mentions national security once, in the context of an item on upgrading domestic governance systems:

The imaginary surrounding AI-powered national security is inward in the Chinese document, covering urban governance, disaster prevention, internet censorship, and law enforcement. In the US document, the implications of advanced technology for national security lie mostly outwards. As of yet, the US is far less afraid of its own people.

The Chinese plan dedicated a specific line item to AI-powered agriculture, a subject which the White House did not call out. This is increasingly relevant in China, as the state pursues food security while rural areas continue to depopulate and starve for labor. The technologies Beijing hopes will solve its food-security dilemma are interesting to note:

Great piece. In times of economic slowdowns, geopolitical opposition and shifts in demographics, drastic measures are called for. China now leads adoption of open-weight LLMs globally. This is going to lead to a wide array of new Agentic products out of China, for cheaper and in more varieties than the rest of the world combined. In the next two years.

Excellent work!