China's Rare Earths Chokehold: A Primer

Farrell Gregory is a nonresident fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation. You can follow his work at @efarrellgregory on X.

Over the course of the last year, we’ve seen China suspend rare earth exports twice, generating a short-lived round of public interest and short-lived “expertise” in America. Each crisis followed a similar progression: an aggrieved China introduces export licensing, effectively suspending US access to certain rare earth elements and downstream products. The American public is subjected to alternating shouts of panic and confident assertions that ‘rare’ is a misnomer and the necessary elements are actually abundant in the Earth’s crust. After a period of confrontation, and likely following concessions on both sides, access is reestablished before too much harm is done.

Examining the differences in each crisis is less important than establishing what is quickly becoming a pattern: China is increasingly willing and able to use its dominance in rare earths as leverage against the U.S. It’s worth noting what a change this is from even five years ago: during the entirety of the 2019-2020 U.S.-China trade war, Beijing never introduced export controls for rare earths, despite making threats to do so. Now China assesses its position differently — they’ve accumulated leverage and they’re willing to use it with increasing frequency.

This frequency might be in part because China’s dominant position in rare earths is a time bomb for both sides. The PRC likely wants to use its REE dominance to extract further concessions before the U.S. manages to defuse this dominance with some combination of reshoring and tech advances.

I think it’s a matter of when — not whether — China decides to activate its standing export control infrastructure. They’ve built up leverage, and over time, that leverage will dissipate. In the near-term future, throttling rare earth and magnet exports is still an effective threat to employ in trade disputes with the U.S. In the medium term, successful reshoring and reliance-decreasing efforts will diminish what concessions China can extract from the U.S.

So, expect the rare earth crisis cycle to play out again. When it does, here are a few clarifications on rare earths that may prove helpful for avoiding the most common misperceptions.

1. They Really Are Rare

You can find trace amounts of the seventeen different elements that we call REEs throughout the Earth’s crust. However, for the purposes of reshoring supply chains, potential mines must meet at least two criteria. First, their deposits of rare earths must be sufficiently concentrated–meaning that the proven reserves yield a much more dense concentration of rare earths compared to the global average. Additionally, the mine must be commercially viable, taking prices, infrastructure, mine life cycle, and financing into account. Rare earth deposits that meet these criteria are, in fact, scarce. One might even say ‘rare.’

This scarcity is demonstrated by the disproportionate output of just a few mines: three in China, one in Australia, and one in California (Mountain Pass). Together, these five mines account for 85% of global output by weight.

But that production is not evenly distributed. While Mountain Pass supplied a majority of the world’s total rare earth oxide (TREO) during the Cold War, it was soon outstripped by Chinese production in the late 20th century. By the 2010s, output from Mountain Pass fell to zero. Even now, with the success of MP Materials, the mine’s new owner, and considerable investment from the federal government, the U.S. accounted for about only about 11% of global TREO output in 2024. Mining rare earth elements at scale in an economically feasible way requires a good site, which is hard to find.

2. Not All Rare Earths Are Created Equal

The reshoring picture gets more complicated from here. The subsection of rare earth elements can be further subdivided into seven light rare earth elements (LREEs) and eight heavy rare earth elements (HREEs). The basis of this distinction varies, although it typically follows the atomic number of the element or its chemical properties. Generally speaking, the full range of REEs is all found together, but in drastically different proportions in different sites. And because the properties and uses of each element vary, a mine that only produces light rare earth elements does not provide the full range of technical capabilities that rare earths enable.

And a LREE-only site is exactly what America has in Mountain Pass. It’s a valuable site that meets critical needs, especially the two most important light rare earth elements, neodymium (Nd) and praseodymium (Pr). When you hear about the importance of rare earths in magnet production, these tend to be NdPr magnets used in automobiles, turbines, robots, and other vital technologies.

But Mountain Pass cannot produce a meaningful supply of heavy rare earths, particularly dysprosium (Dy) and terbium (Tb), which are used in Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets. Utilizing the properties of heavy rare earths, these performance magnets are capable of withstanding more strain and higher temperatures than NdPr magnets. Absent a domestic source, any disruption to America’s heavy rare earth element supply chain leaves us entirely unable to produce a wide range of advanced electronics.

That’s why the last two rounds of Chinese export controls have targeted heavy rare earth exports. It’s well known that China mines 70% and refines 90% of rare earths, but when it comes to heavy rare earths, Chinese production dominance jumps to 99%. Assuming that the DoD bet on MP Materials succeeds and America develops a domestic supply chain for light rare earth mining and NdPr magnet production — a scenario which is far from guaranteed — we would still rely on China for essential heavy rare earths.

3. China’s Dominance is More Than Just Refining

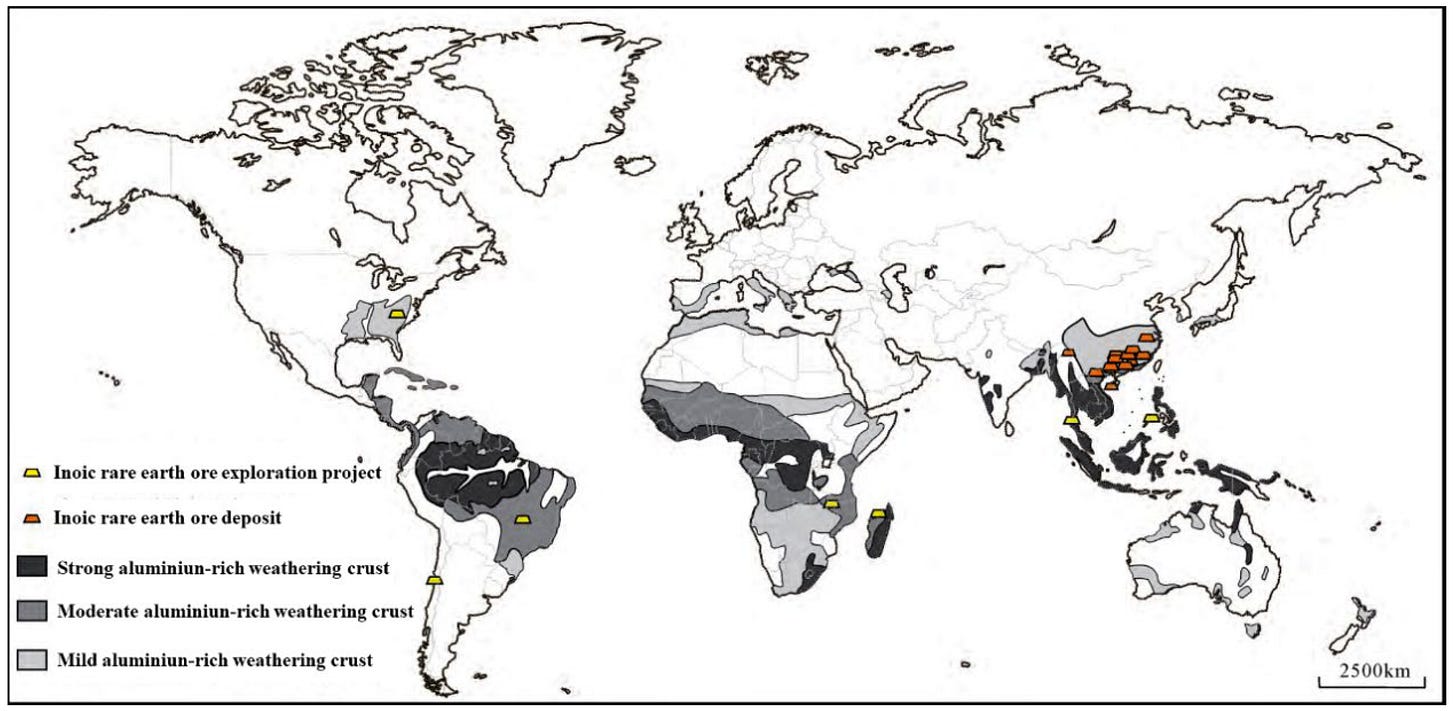

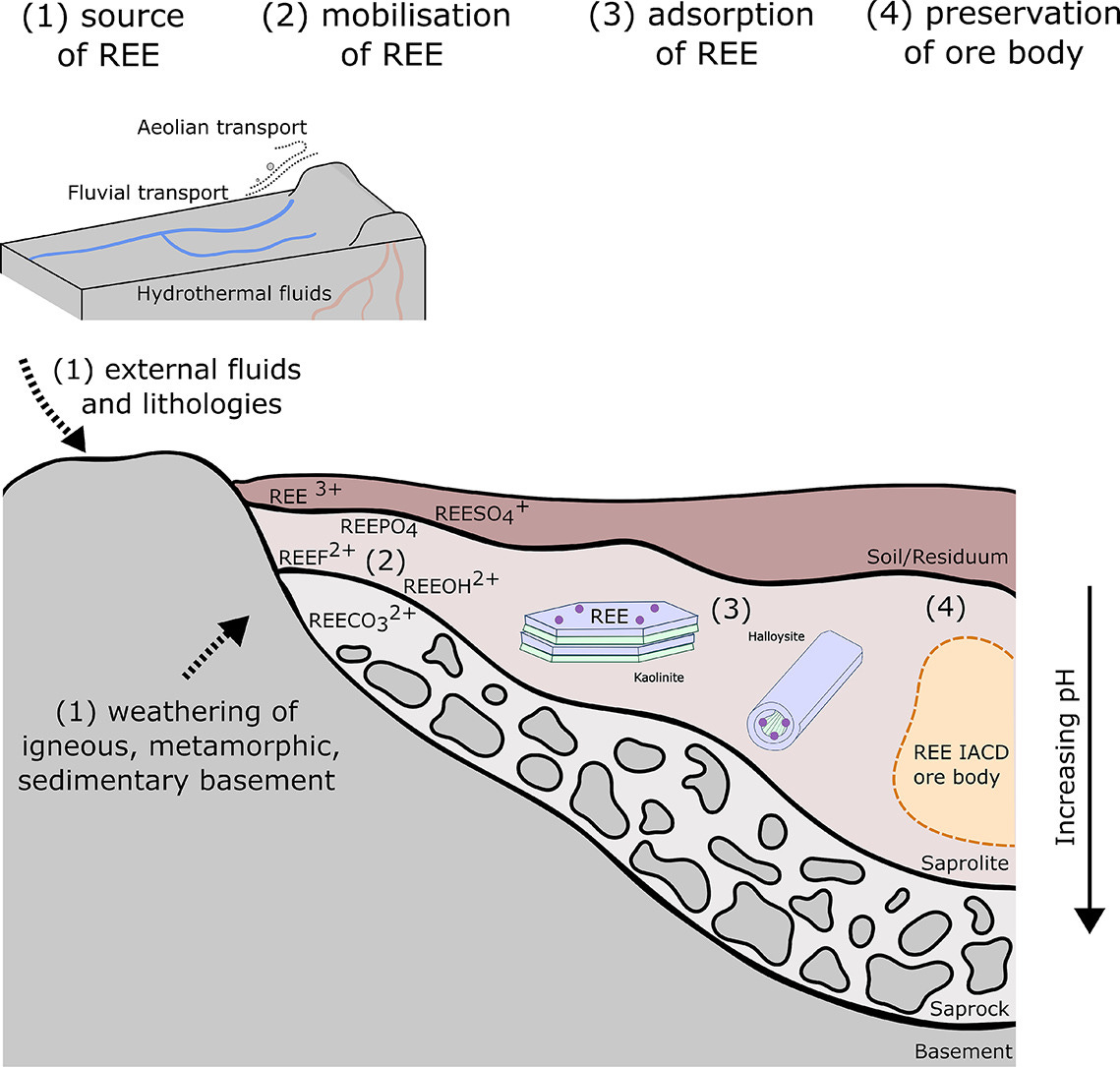

Another common line about China’s rare earth dominance is that they only have an advantage in refining rare earth oxides (the intermediate step between the extracted earth and refined metals). That is where they’ve developed a skilled workforce and proprietary processes since the 1990s. But that’s still an incomplete picture. The primary reason that China is so dominant in rare earths, and especially heavy rare earths, is advantageous geology.

Different concentrations of rare earths tend to occur in different geological and mineral environments. Sites that are disproportionately rich in heavy rare earths tend to be ionic clay deposits. The scientific explanation for why is too long for this article, but in short, Southern China’s topology, geography, and tropical climate proved to be an ideal environment for easily extractable ionic clays to absorb REEs. It’s worth pointing out that these smaller HREE mines are separate from China’s big three (Maoniuping 牦牛坪, Weishan 微山, and Bayan Obo 白云鄂博), which primarily provide LREEs. The southern HREE mines were less regulated, more artisanal, and especially environmentally damaging. The easiest way to extract the elements from the clay is by injecting chemical fluids into the terrain, producing toxic waste, contaminated soil, and an element-rich liquid from which the HREEs are extracted.

Increasingly, this HREE leaching takes place in environmentally similar sites across the border in Myanmar. Not only does this provide a new source of heavy rare earths within easy reach of Chinese companies, but environmental protections are also even lower (or nonexistent) in a country engaged in prolonged civil war. Despite the fact that Myanmar is an unreliable provider of rare earths — the rebels who captured mines in late 2024 temporarily blocked Chinese access — the geology is so ideal that it remains an attractive source.

While the ionic clay environment in Southern China is particularly enviable, it is not the only possible source of heavy rare earths. Back in 2019, the U.S. Geological Survey released a paper examining the viability of American deposits. There are good reasons to assume that any HREE mining in the U.S. would be held to a higher standard than in-ground chemical injection in rebel-controlled Myanmar. However, concern around environmental externalities would still be a substantial barrier to bringing the HREE supply chain fully stateside.

Brazil, with the world’s third-largest REE reserves, has potential, but it would need to dramatically scale its output to replace Chinese supply. In 2024, Brazil mined only 20 tons of rare earth oxide. China mined 270,000. This scaling problem still hasn’t stopped American officials from buying up future production in Brazil(?), at the expense of European access.

Getting Ready for Round Three

Before the next round of Chinese export controls comes down on the US (we’ve already seen Japan get hit just this week!), these geological dynamics will shape what policies the U.S. could pursue. Since the rare earth détente, the Office of Strategic Capital has invested $1.4 billion in a deal with ReElement Technologies and Vulcan Elements to expand domestic magnet supply chains. The Department of Energy’s Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation is putting $134 million towards rare earth production. That comes in addition to the $1 billion in Congressionally-appropriated funds that are being directed towards REE projects.

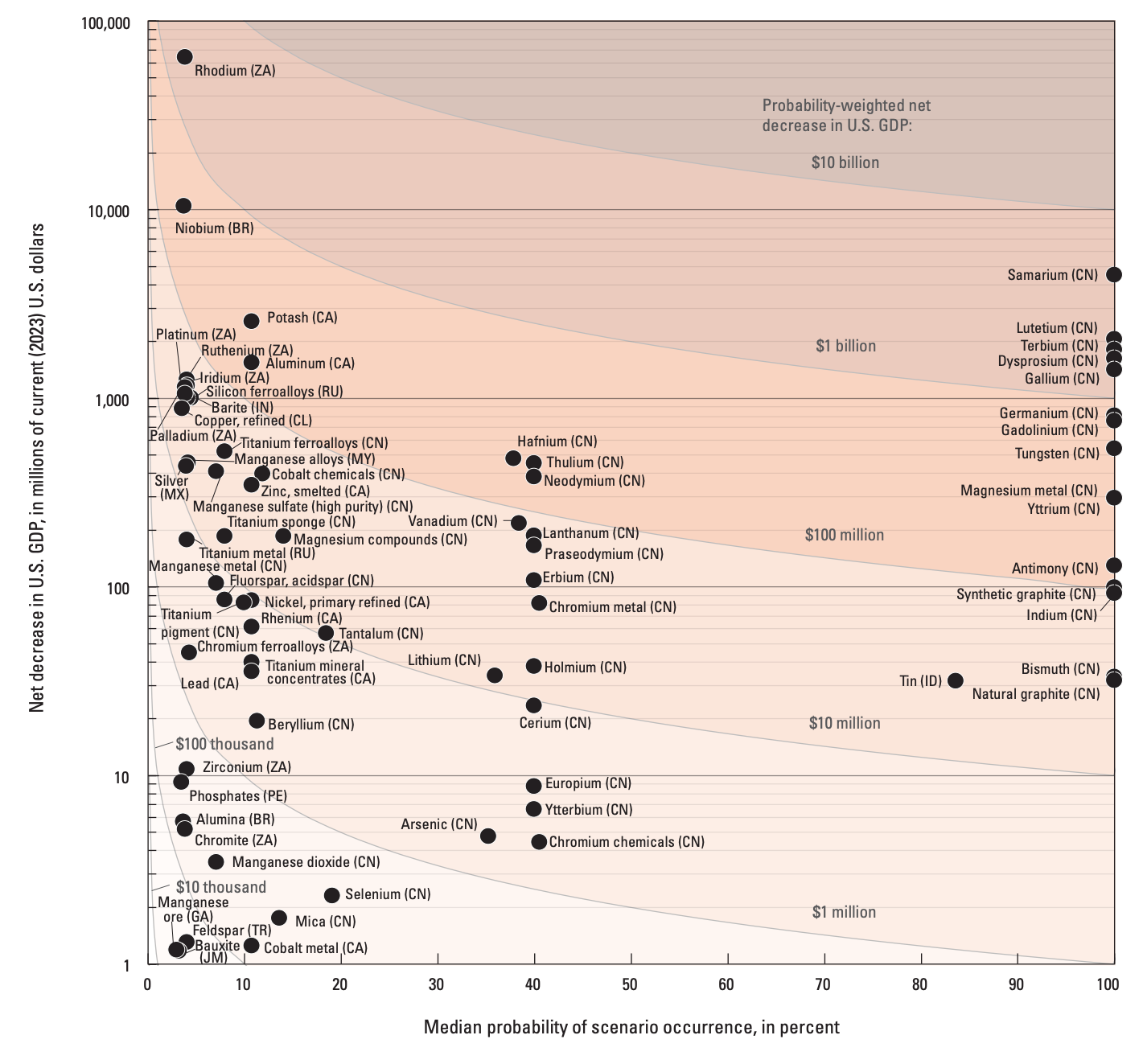

The Trump administration is clearly prioritizing reshoring rare earth production over other minerals and materials, in my view a positive development. The broader “critical mineral” category gets a lot of attention and is too frequently treated as a single problem with a single solution. But as the 2025 USGS Critical Mineral List makes clear, some minerals are more critical than others.

Rare earths, alongside a few other minerals, stand far apart for their strategic value and the likelihood that their supply chain will be disrupted. Dozens of other minerals are either less subject to Chinese manipulation or are less consequential. Ultimately, the U.S. government is working with a fixed pool of capital and expertise to lessen Chinese influence over critical supply chains. Programs that treat all materials as equally consequential, for whatever other benefits they may have, aren’t likely to move the needle. Actually reducing reliance on China for rare earths will require focused investment and accounting for these geological and chemical realities that give China an enduring advantage.

Thank-you for a very thought provoking article. A brief look at Volume 3, Chapters 13 and 14, of Sir Winston Churchill's "The World Crisis," clear demonstrates that modern warfare can not be fought without the necessary minerals and chemicals. As technology as advanced, the types of minerals have changed, but the fundamental need is the same. (Timber to build the British Navy was, until the end of the American Revolutionary War, provided by the New England colonies. Following the war, Britain turned to the Baltic region, another example of natural resources dictatating policy. Just the rambling thoughts of an old hermit.)

Mr. Gregory, a lucid analysis. You are right to look past the 'Light Rare Earth' hype.

1. The Geography: You are correct that Brazil is structurally insufficient. As a Deep Insider, let me confirm your suspicion: Greenland's Kvanefjeld is indeed the only geological anomaly outside China that matches the Scale and Heavy Ratio (HREE) of our Southern mines. It is the only asset that truly matters to System A.

2. The Fallacy: However, you—like the Pentagon—are falling into the 'Geological Trap'. You see the 90% refining dominance as a byproduct of geology. It is not. It is an independent Technological Black Box.

To turn Kvanefjeld's ore into 99.99% Dysprosium is not 'mining'. It is Extreme Chemical Engineering. It requires balancing P507 extractants across a cascade of 5,000+ mixer-settlers (混合澄清槽). It is a process of 'Chemical Torture' where a single pH fluctuation ruins the entire batch.

The Brutal Truth: Washington thinks it lacks the 'Dirt' (Dysprosium ore). In reality, Washington lacks the Engineers who can play a 5,000-stage simultaneous chess game with fluids.

System A is buying Real Estate. System B is running an Operating System. We call this system R.I.C.E., and the 'Chemical Wall' is just one of its firewalls.