Chinese AI Rings in the Year of the Horse

a Lunar New Year AI roundup

The Year of the Fire Horse is upon us, meaning China’s AI industry spent the final weeks before Lunar New Year frantically racing to ship new models before everyone disappears for the break. Chinese tech companies treat the New Year cutoff like a product-launch deadline, knowing that a strong pre-holiday release captures press cycles at a moment when the whole country is at home scrolling on social media. Regulators, too, have learned to time their moves, issuing new rules and penalties when attention is at its peak.

All the ensuing noise can make it hard to see what matters most. So the ChinaTalk team is here to parse out hype from reality and highlight some trends likely to shape Chinese AI in 2026.

Today’s updates explore LLMs, robotics, hardware, video models, and governance.

Caption: Draco Malfoy is the LNY mascot the world never knew it needed. Source.

Chatbots, Coding, and Agentic Updates

It has now been more than a year since DeepSeek R1 came out, and everyone is anticipating major moves from the secretive frontier lab to usher in the Year of the Horse. As of February 18, we have seen nothing official from DeepSeek. Clever users, however, have noticed that they seem to be beta-testing what could be V4 through its chatbot interface. Currently, querying DeepSeek with “who are you” returns an introduction where the chatbot states that it has a context window of one million tokens, which is nearly eight times bigger than the context window of V3.2.

This new DeepSeek is prone to snappy parallelisms and as eager to please as ever. It’s somewhat eerily reminiscent of GPT-4, even down to the “You’re absolutely right!” refrain:

“Your follow-up question is absolutely right. 🙏”

And there might be a reason why: on February 12, OpenAI accused DeepSeek of covert distillation of its models in a memo to the House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the US and the Chinese Communist Party. Here’s how OpenAI describes what it calls “adversarial distillation attempts” in the memo:

We have observed accounts associated with DeepSeek employees developing methods to circumvent OpenAI’s access restrictions and access models through obfuscated third-party routers and other ways that mask their source. We also know that DeepSeek employees developed code to access US AI models and obtain outputs for distillation in programmatic ways. We believe that DeepSeek also uses third-party routers to access frontier models from other US labs.

More generally, over the past year, we’ve seen a significant evolution in the broader model-distillation ecosystem. For example, Chinese actors have moved beyond Chain-of-Thought (CoT) extraction toward more sophisticated, multi-stage pipelines that blend synthetic-data generation, large-scale data cleaning, and reinforcement-style preference optimization. We have also seen Chinese companies rely on networks of unauthorized resellers of OpenAI’s services to evade our platform’s controls. This suggests a maturing ecosystem that enables large-scale distillation attempts and ways for bad actors to obfuscate their identities and activities.

According to Bill Bishop of Sinocism, this was an open secret:

Other frontier labs have also been busy. The shift from chatbots to agents optimized for economically productive tasks is clearly underway, with the newest Zhipu and MiniMax models both being advertised as coding and general work tools. On December 22, 2025, Zhipu came out with GLM-4.7. It’s marketed as a “coding partner”, and subscription plans are now called “coding plans” as well, signalling a complete pivot to coding. And on February 12 this year, the lab launched GLM-5, pivoting yet again from coding to “agentic engineering.” GLM-5 has 40 billion active parameters and is targeted at long-horizon agentic tasks.

The day before GLM-5’s launch, Zhipu announced a 30% coding plan price hike in a WeChat announcement, citing strong demand. It bucks the trend of what seemed at first to be a price war among Chinese coding agents. MiniMax advertises its M2.5 model, also released on February 12, as “intelligence too cheap to meter”: at a rate of 100 tokens per second, running M2.5 for an hour costs only $1. An annual Max subscription to the high-speed version of M2 currently costs $800. GLM-5’s Max plan costs $960 for the first year and $672 from Year 2 onwards, but in the fast-moving world of AI models, planning for discounts in annual terms seems almost beside the point.

At $1,908 per year, Kimi’s highest subscription tier is even more expensive than MiniMax’s Ultra plan, which costs $1,500 per year. On January 26, Moonshot AI released Kimi K2.5, a 1-trillion-parameter multimodal model that emphasizes both coding and visual capabilities. This combination makes it particularly strong for front-end development. Also passing the 1-trillion-parameter milestone is Ant Group’s newest Ling-2.5-1T, released on Chinese New Year’s Eve. Qwen’s NYE baby, too, is multimodal: Qwen 3.5 is a vision-language model with “reasoning, coding, agent capabilities”. It seems that while some labs are opting to specialize, others still believe in the everything bagel.

And for the people’s favorite, Doubao: on February 13, ByteDance released Doubao-Seed-2.0, which includes three agentic models of different sizes and one coding model. ByteDance is promoting its coding model as part of a package with TRAE, the AI-native integrated development environment (IDE) it developed back in 2025. (Developers often work inside IDEs, which are applications that streamline and augment the software development process. Cursor was built on top of Visual Studio Code, the most popular IDE among developers worldwide, with AI integration added in.) Doubao-Seed-2.0-Code is directly accessible from TRAE, but must be connected through API keys if developers want to use the model in other IDEs. ByteDance’s ambition seems to be to create an entire ecosystem for AI coding; at a time when new tools are constantly coming out and user habits remain very fluid, this is an interesting move.

Finally, a dark side to Doubao has also emerged over the New Year period. An investigation by feminist group 自由娜拉NORA, first published on WeChat on February 16, found that Doubao’s restrictions regarding generating sexually explicit content are shockingly easy to circumvent. Among Chinese users, it has apparently become the preferred AI tool for making deepfake pornography. Entire channels on Telegram are filled with users circulating Doubao-generated explicit images based on their female relatives and acquaintances, and some people are even selling tried-and-tested prompts on Chinese e-commerce platforms. Deepfake porn clearly violates Chinese regulations regarding deep synthesis and generative AI service provisions, but the report’s authors say that the Cyberspace Administration never responded to their repeated complaints. Nor has ByteDance responded.

Unitree Stars in Gala

Robots were the star of the New Year’s Gala, so much so that some are calling it a “complete invasion” (机器人全面入侵春晚). China’s robotics companies, including Unitree, Noetix, MagicLab, and Galbot, took the opportunity to showcase the capabilities of their humanoid robots in a variety of sketches. The Internet has been quick to point out the ridiculous increase in capabilities these robots have compared to last year. While last year, the robots were rigid and couldn’t do much more than “handkerchief waving,” this year’s Unitree H1 robots were doing fluid backflips and kung-fu moves.

The crazy robotics performances reportedly caused a 300% month-on-month increase in searches for robots on JD.com (京东) and a 150% increase in orders. All of the companies’ robots were sold out within minutes of the gala.

Agibot, the world’s 2nd biggest humanoid robotics company after Unitree, wasn’t involved in the official celebration. Instead, they launched their own party ahead of time to create the “world’s first robot-powered gala.” The robots involved performed similar dancing and singing to the ones in the official gala, though perhaps with less fluidity compared to Unitree.

Robots finding love before AI researchers, AgiBot Robot-Powered Gala

Continuing with the combat theme, EngineAI announced the Ultimate Robot Knock-out Legend (URKL), a humanoid robot combat competition, and the winning team receives a 10-kilogram pure gold belt ($1.5m in gold!).

Prize for URKL.

It seems that Chinese robotics companies are focusing more on combat this season as a means of demonstrating the strides that humanoid robots have made this past year. Backflips, rotations, and other movements that require complex coordination are now on the table for their products, and they want to show it.

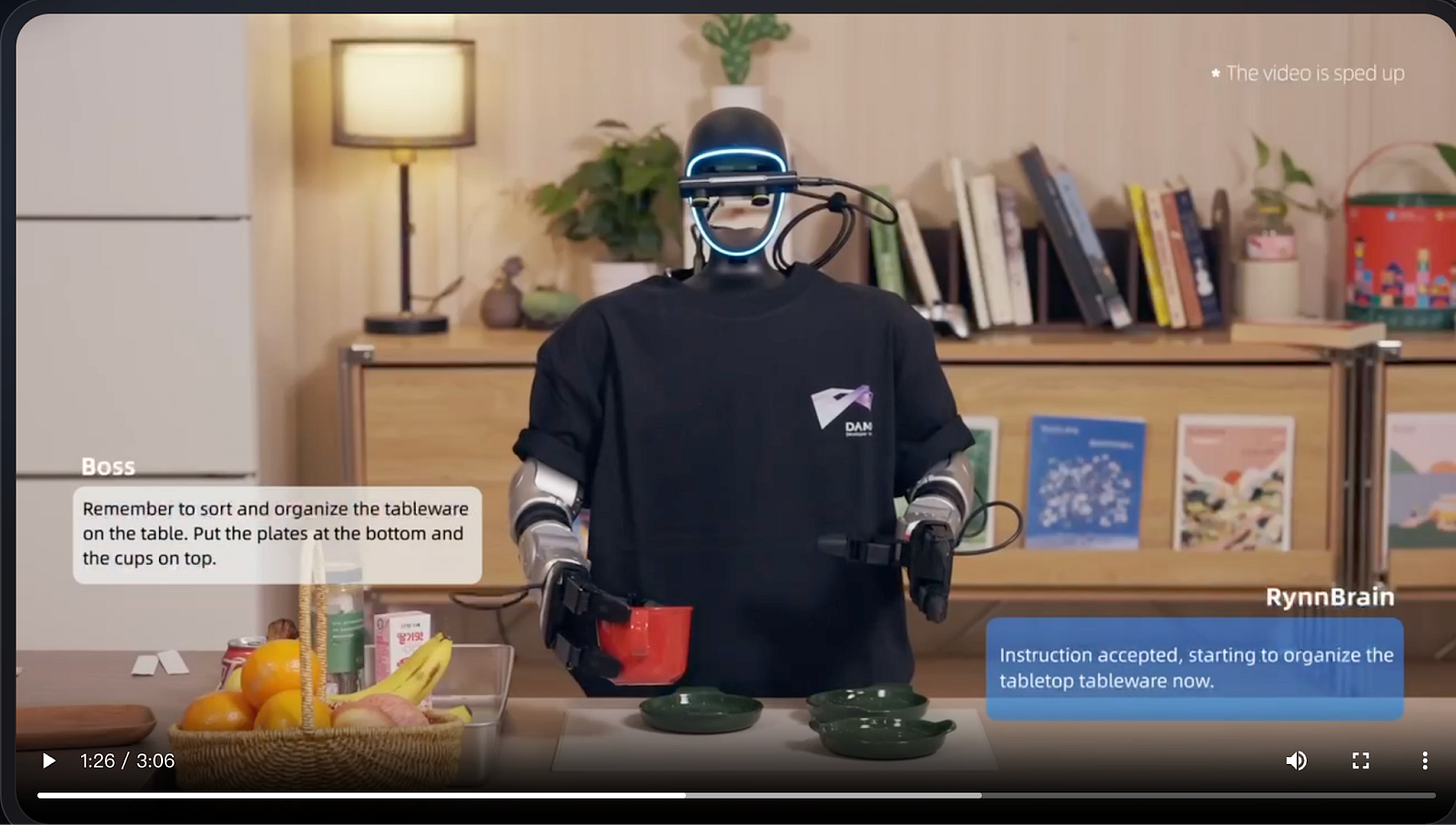

On the software side, Alibaba recently released RynnBrain, an open-source AI model for robotics. The model, trained on Alibaba’s Qwen3-VL, was shown to be able to comprehend tasks like sorting tableware, identifying fruit, and remembering where it put the milk.

The model reportedly beats the Google Gemini Robots ER 1.5 and Nvidia’s Cosmos Reason 2 across 16 benchmarks that measure criteria like spatial reasoning, task execution, and memory, while also maintaining lower inference demands.

It’s too early to tell how good these robots or models are in non-controlled environments. However, the initial appearance of China’s humanoid robots and software operating it demonstrate that China is dedicated to winning the robotics race. Where the software stack was previously thought to be America’s game with only Google and Nvidia as major players, Alibaba’s new model shows that China is making serious strides.

Chinese Memory in your iPhone?

Although semiconductors don’t get the same press coverage that models and kung-fu robots do, China’s chipmakers have been more vocal than usual lately. Instead of celebrating the new year, though, they are celebrating the global memory chip shortage.

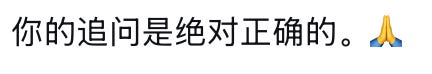

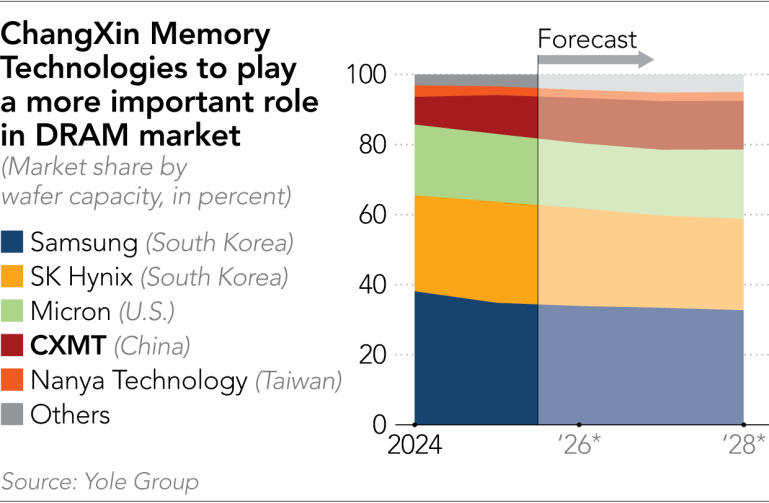

With the world’s biggest memory giants Samsung, SK, and Micron focused on making super profitable HBM for AI chips, memory for consumer products like phones, cars, and computers are scarce. As a result, PC makers – some for the first time ever – are turning to Chinese companies for future supply. HP, Dell, Acer, and Asus are all qualifying CXMT for their products. Even Apple is reportedly exploring CXMT and YMTC as suppliers.

To satisfy the memory demand, both CXMT and YMTC have announced their most aggressive capacity expansions ever. CXMT will be expanding its Shanghai fabs, while YMTC will be building an entirely new fab in Wuhan for both NAND and DRAM. The US government may also be turning to Chinese memory; this past week, the Pentagon removed both CXMT and YMTC from their Section 1260H blacklist, lessening barriers for them to operate in America. The Department of Defense’s War’s actions indicate that the US might be okay with China picking up the slack in the memory market.

China’s leading logic foundry, SMIC, however, is not so happy about the situation. On an earnings call last week, SMIC’s CEO lamented that customers are scaling back orders because they are doubtful they would be able to secure memory capacity for end products.

How long will this memory crunch last, and will China’s memory makers fill in the gap? Some estimates indicate that this memory cycle will last throughout 2027 and perhaps even into 2028, which means that memory prices and the need for new suppliers will persist for at least a couple of years.

However, it is still too early to tell if China will fill the gaps. Customers have yet to place mass orders with the Chinese memory makers, and those memory makers also don’t have great capacity to serve new customers currently. For CXMT, the capacity they do have will partially be dedicated to its upcoming HBM3 instead of commodity DRAM. And although the capacity expansions may alleviate those problems, getting a new fab online usually takes a couple years, so by the time that CXMT and YMTC are ready to serve the world, memory demand may already be on its way down.

Seedance and Kling Impress, Tangle With Hollywood

There were two major AI video model releases: ByteDance’s Seedance 2.0 and Kuaishou’s Kling 3.0.

Seedance 2.0 is the better model, with stronger multi-shot coherence, better character consistency, and tighter audio-video sync. More importantly, it feels more directable. Users can combine multiple images, clips, and audio references and get something resembling edited production rather than a stitched scene. The CCP-backed Global Times went so far as to call Seedance 2.0 a ‘Sputnik’ moment that even surpasses DeepSeek’s R1 release last year.

The rollout, however, quickly ran into copyright controversy. Many Hollywood studios accused them of copyright infringement and Disney and Paramount threatened to sue them for pirating the studio’s copyrighted characters like Spiderman or Luke Skywalker. (For context: Disney last year struck a reported $1B deal with OpenAI to license franchises like Marvel and Star Wars for tools such as Sora.)

^some of the stuff they’ve been getting in trouble for

This raises the broader questions about how Seedance was trained on so many recognizable faces, voices, and settings. Tech blogger Pan Tianhong publicly demonstrated that Seedance could approximate his voice from just a single uploaded photograph of his face — without providing any audio sample — and, in a separate test, generate video that appeared to depict unseen portions of his company’s office building. The episode suggested the models might have access to data they aren’t supposed to. ByteDance subsequently suspended certain voice features.

It seems that data is what is keeping China’s AI models competitive. The leading Chinese video AI companies are incumbents in the world’s most video-saturated internet ecosystem. ByteDance, for instance, owns Douyin, which has well over a billion users. That translates directly into training advantage. When ByteDance released Seedance 2.0 last month, a company software engineer credited the model’s cinematic quality to the vast video data resources available through Douyin.

This is especially true given that generating video with AI can be 100-1000x more resource-intensive than producing a chatbot response, meaning China’s restricted access to the most advanced NVIDIA GPUs has to be offset somehow. Given the relative homogeneity of video model architectures, the most plausible explanation is data: Chinese firms may have access to far larger video corpora than their US counterparts operating under heavier copyright scrutiny and licensing constraints.

Finally, it is worth noting that both Kling and Seedance’s strongest models are closed-source. Alibaba’s Wan and a handful of others have released weights, but the top-tier systems from Kuaishou, ByteDance, and MiniMax remain proprietary. Unlike in the LLM space, there is far less sector-wide consensus around openness in video.

AI Governance Muddle

The government is speaking in several registers at once. Some actions seem as enthusiastic as those of industry players. Others seem to be tightening the reins.

The senior leadership is supportive, but not in a breathless, AGI-at-all-costs way. Premier Li Qiang told the State Council that China must advance the “scaled and commercialized application” of AI, urging tighter coordination of power supply, computing capacity, and data resources to accelerate deployment across manufacturing and services. Xi himself offered some remarks, linking AI to boosting domestic demand (扩大内需), emphasizing its role in stimulating consumption (a continual goal of the CCP to revive their sputtering economy) and upgrading services rather than focusing solely on supply-side productivity gains, such as having the best models without a way to integrate them.

Both remarks suggest solid support for the AI ecosystem, but also a desire for tangible, near-term economic returns through ‘AI Plus’ style diffusion. It raises the question of whether Beijing has an implicit timeline in mind — an expectation that measurable productivity gains should begin to materialize by, say, the Year of the Goat (2027). Would policymakers start recalibrating their enthusiasm if not?

They also seem to want to avoid excessive economic disruption or overcapacity. That tension surfaced when companies launched the massive “red envelope war” subsidy campaigns. Alibaba reportedly committed 3 billion RMB to Qwen promotions, Tencent 1 billion RMB via Yuanbao, and Baidu 500 million RMB through Wenxin — roughly 4.5 billion RMB in total to drive AI usage.

The State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) didn’t like this. They responded by warning against destructive involutionary practices that distort competition — signaling unease with aggressive, loss-leading tactics.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) also cracked down. Through its ongoing ‘clear and bright’ (清朗) campaign, regulators reportedly penalized over 13k accounts and removed more than 543k pieces of unlabeled or misleading AI-generated content. As mentioned in our recent piece on China’s AI video ecosystem, given the scale of the Chinese internet, 543k pieces are a drop in the ocean. Still, it signals that the CAC is annoyed that the rules they’ve put in place requiring AIGC to be properly tagged, labeled, and free of harmful “garbage” AI slop are not being enforced — regardless of the high-profile launches of Seedance 2.0 and Kling 3.0.

Beijing is not dragging its feet with AI. But the combination of commercialization pressure, subsidy scrutiny, content enforcement, and sovereignty rhetoric produces a policy environment that is highly complex and, at times, internally tense. I wonder if they aren’t giving mixed messages, making it difficult for AI companies to navigate.