Ed Luttwak on Military Revolutions

The Machiavelli of Maryland

This show’s guest is the legendary strategist Edward Luttwak — the Machiavelli of Maryland. He’s consulted for presidents, prime ministers, and secretaries of defense, and authored magnificent books on Byzantine history, a guide to planning a successful coup, and an opus on the logic of strategy and the rise of China. He raises cows, too.

This is the full-length transcript of our conversation.

Our conversation today covers…

Luttwak’s childhood and formative encounters with war, including an early fascination with the mafia in Sicily,

Technological step-changes in warfare,

Books that shaped Luttwak’s view of war, from Clausewitz to the Iliad,

The costs of “removing war from Europe” post-1945,

China’s strategic missteps,

The psychology of deterrence, including what kind of Middle East policy would actually deter Iran,

The strengths of democracies vs. autocracies.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app. Note, we recorded this in the summer of 2024.

A Childhood Interest in War

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about your approach to history. Because in reading, ingesting a lot of you over the past month or so, you have this very unique approach, which is almost like an everything-everywhere-all-at-once view, both when you’re doing your Byzantine stuff as well as the more contemporary work looking at the modern world, which is not something you see very often.

I guess there aren’t a lot of historians who are fluent in as many eras and regions as you are, or even try to synthesize as much and draw from as many different examples in trying to pull out threads and a thesis. Maybe, how did you come to this approach? What inspired it? How did you develop this style?

Edward Luttwak: Well, if I were to answer honestly, you would realize that I invented none of it. I can’t claim credit for having initiated anyway. Accidents of life brought me successfully into contact with people of all kinds.

It started with the fact that I was born in Transylvania, in Banat, actually, Northwest Romania, which is an area that was within Romania, but was not Romanian. The population included Serbs, there were Hungarians, there were Germans, Catholics, German Protestants, there were Hungarian Calvinists, Hungarian Catholics, Jews of different kinds, and of course, Romanians as well. It was the only truly multinational part of Europe, the only multinational place in the whole of Europe.

Down the main boulevard where the house where I was born was, there was the Serbian Cathedral, the Orthodox Jesuit, Romanians, the Hungarian Catholic Church, the Calvinist Church, the German Lutheran and so on. There were schools for all these languages, and people conversed in them. It was truly multinational. The Romanian government had a very light hand because it was by far the most prosperous part of Romania, which generated all the high tax revenues, and they didn’t want to mess with it. They didn’t fly to Romania — There was no brutal imposition of Romanian uniformity, of anything of the sort.

I was born in that environment. My parents were very enterprising people. They honeymooned in 1938, and they went to Bali, because the KLM had just started flying boat service to Surabaya, which is across from Bali. The Americans had made a film about Bali Ha’i [Ed: the musical South Pacific].

There were no hotels in Bali, but it was a very fantastic place. All the women went around topless in those days, because it was a traditional Hindu way to do it.

My father’s business was import-export. Not anything modern, but he imported dried fruits from Turkey and black olives from Greece, anchovies from Catania, oranges from Palermo, all the traditional things. He was traveling all the time, so it was very international.

Because of that, he took us out of Romania a week before the communists slammed down.

Jordan Schneider: What was their experience of the war?

Edward Luttwak: Well, the experience of the war was that — I don’t want to go into details, but the fact is that the only two Jewish communities in all of Europe where nobody was deported, and nobody was killed. Those were in Arad and Timișoara — the Banat communities. There, the population increased during the war, from the Atlantic to the Urals, all other communities either disappeared or went down drastically 10%, 5%, 3%, but there they increased.

You’ll notice that if you look for it in the vast stereography of the Holocaust, you will not find the history, because even when the Holocaust Museum, archivists, whatever they are, historians, did a big thing on Romanian Jewry, it was all about martyrology. They died here. They died there. But for the place where Jews survived, historians didn’t write anything about it. They were not interested. The leadership of the Jews in these two areas acted as if the leaders of a nation under attack and deployed the resources, did everything and used every method. In other words, it was a survival that was not accidental. It’s interesting that these stereographers are not interested in it.

From leaving everything behind, and there was a lot to be left behind, my father, my mother, a lot, they went to Italy with nothing. My father immediately went to Palermo, Sicily, where his few thousand dollars became millions in three years, simply because he read the Swiss newspaper, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, every day. Zürich is the headquarters of the reinsurance industry. There are people sitting in Zürich who are very interested in oil wells after the coast of Mexico. There were detailed articles and notes about everything, including the British National Health Service, which he read and which promised to give oranges to every British child.

My father, who had been to England and knew there was not a single orange tree, went to Palermo with the highest concentration of orange trees and started sending oranges to England. Arriving with three children and virtually no money, within three years, he started building a factory in Italy, because he had a perverse passion for plastics, which were new at the time.

Anyway, I went to school in Palermo. My history really starts there, because the local schoolteacher refused to teach Italian. I didn’t know Italian. I go to school, I had to learn Italian. He refused to teach Italian. He said, “Nobody speaks Italian here. Everybody speaks Sicilian. What’s the point of me teaching you Italian?” He taught Latin. He himself had been trained as a Latin teacher. Couldn’t get a job as a Latin teacher. Got a job as an Italian teacher, but with total indiscipline, and nobody stopped him, he just taught us Latin.

I was there only for elementary school, and I was there for only four years. Then, I went to a British boarding school. In those days, Latin and Greek were still very important in British education.

Another thing they had was a cadet corps. Britain still had an empire, and it would have for another 20 years or so. In the boarding school, you have a cadet corps. At the age of 13, you have a kid’s uniform, and you have, what you call, .22, a light rifle to practice with. Then, a couple of years later, you get a real rifle, and so on.

Going to boarding school and starting on Greek there, Latin and Greek rifles for that corps and so on. The boarding school was a Jewish school.

Jordan Schneider: Oh, interesting.

Edward Luttwak: Yes, but it was a Jewish school that derived directly from the Yeshiva of Lithuania. The Yeshiva in Lithuania, uniquely, was big on sports. In Lithuania alone, the orthodox Jews that you see running around and so on, they had sports. They had men’s salah, incorporate salah, healthy mind. Our rabbi was an athletic guy. We were on the Thames River, and used to swim up and down. We all did. We had boxing. We had cricket, of course, and football. We also had boxing and fencing as a big deal.

Cadet corps, boxing, fencing, swimming, not fretting and fussing, and cold showers and all that stuff of a British boarding school in the 1950s, that was a very profound thing. Also, our teachers were basically German-Jewish refugees who had been university professors. Our history teacher, whose name was Friedman, was a professor at the University of Bonn, the later federal capital, and so on. They brought that level of teaching.

They were not all Jews. The chemistry professor was an Englishman. There were a couple of non-Jewish teachers there who were very vigorous representatives, enthusiastic and so on. Of course, they were living an upper-middle-class life. Each of them, the boarding schools had a substantial house to live in and so on. The local farmers’ daughters would come in to help with the cleaning and so on.

They were the people who would teach things that would uphold the society, which had rewarded them with this upper-middle-class lifestyle in a beautiful place along the Thames. I didn’t know English — of course, I had to learn.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay there for a second with this world you were living in. What was everyone’s relationship to the Holocaust and Judaism?

Edward Luttwak: My parents were invited to participate in Holocaust. They never did and continued to have absolutely no interest in it.

Jordan Schneider: What does “participate in the Holocaust” mean?

Edward Luttwak: Well, you were invited to go and be deported. People like my parents, they persuaded the entire community to simply refuse.

Jordan Schneider: During the war?

Edward Luttwak: During the war. They did not participate in the Holocaust. They considered the Holocaust as a defeat of the Jewish leadership, secular and religious. All these self-important people who were the leaders of the Jewish community around Europe, from the Atlantic to Russia — they all failed. They failed to understand that there was a threat. They failed to organize, they failed to use the resources. They failed to do a lot of things.

A local rich guy, really rich guy, was a man called Neumann, actually, Baron Neumann, no less. He called the young people, including my father, and said, “I’m very rich, and none of my money will serve me if I’m deported. You young fellows, if you have any way of doing anything useful and have a high probability, I’ll fund it. If it has a low probability, I will also fund it. If it is just a possibility that it might be of any use, I will fund it.” That was one thing, using money like that.

The other was the understanding that when there’s a war, you have to be ruthless. There were ruthless actions taken that were effective. Afterwards, my parents never, ever mentioned it. I never heard a word about it, nor did they ever talk about what they left behind.

I actually visited the house when I got an honorary degree in my hometown, Arad. If I’d owned that house, I would have boasted about it, because it was made of marble from Italy and all kinds of things. They never, ever mentioned the Holocaust. They never mentioned everything they left behind. They were strictly forward-looking. They were not unique in this, because actually, a lot of even Holocaust survivors, who went through concentration camps, were very dynamic people, actually, after the war. Very dynamic. Some of them became car dealers in California and things like that. Others went to Israel and created a state, of course.

My good life were schools. My elementary school in Palermo, because all the rich families sent their children to Tuscany so they would not speak Sicilian. They would not be contaminated by speaking the local Sicilian. My parents were enthusiastic about Sicily. I went to the school, where I did not learn Italian, but I learned Sicilian and Latin.

Then, I go to boarding school, where my teachers are refugee professors from German universities. Alongside the Thames River with a six-foot rabbi who believes in physical athletics. He was a really athletic guy, and he really believed in mens sana in corpore sano. We did all the sports very seriously.

The cadet corps was wonderful because the teachers were sergeants. All of the sergeants had been through World War II, because we’re now in the early 1950s. Actually, in our case, it was the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. They had all been in the Eighth Army. They went from North Africa, Italy, and so on. When they were teaching us how to use weapons, they had real knowledge.

Also, Britain still had an empire. Everybody in that school was looking forward to having a career in imperial policing and so on. Along the way, you do your years in uniform, and then you do whatever you want to do. That applied even to Jewish kids or the sons of dentists who wanted to be dentists. They didn’t want to be dentists without doing not just a national service, four or five years, that kind of stuff.

These were all things that I can claim no credit for at all. It was accidental. It was my parents who brought me to Sicily, and therefore I learned Sicilian, and therefore I learned many, many things, including the art of violence, controlled violence. Even as very young children in Sicily, you could never escalate fights, because if you won the fight over the other 8-year-old, the 10-year-old would come, the brother. Then, another brother, and then the parents would come out, then guns would come out.

You learned, actually, the coherent use of force, which is very typical of the culture, which is the mafia culture, really, is that you don’t waste force. If you go around punching people for no reason, this is really terrible. All these other stuff were all giving to me without any credit on my own, any merit on my own. It was what you might call an extraordinarily fortunate childhood for somebody whose final destination was not to paint, or make films, or build houses, but to do what I have done, which is to study war and all these other things. I was given all this right at the start.

Jordan Schneider: Why should people study war?

Edward Luttwak: Well, the reason I studied war is that I was coming from a World War II family, let’s call it that, arriving in Sicily, where the controlled use of violence was the essence of society — the Italian state pretended to rule Sicily. As a matter of fact, they still pretend to rule Sicily today.

Sicily was actually ruled by the mafia. The mafia is not the mafia of the films and so on. The heads of the mafia were lawyers, notaries, dentists, surgeons, and people like that. Yes, it was something. Then, I was very determined to take part in any war I could take part in, because I did not want to miss the experience of war.

I read Churchill’s book, The River War. He was very poorly educated. He never really studied at university or anything of the sort, but he was a young subaltern, a young officer in the war against the Mahdi in Sudan. He was a cavalry officer. He wrote The River War, which was a book about his experiences. He took part in the charge of the Battle of Omdurman, which is really just about the last charge of cavalry with swords drawn. He published his book in London very soon after, which was immediately reviewed by the people.

The first people who read the book had taken part in the war against the Mahdi in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. In other words, he had to tell the truth because the book that appeared was read immediately by the other officers.

He, in that book, already revealed an understanding of the basic dynamics of war, which would enable him to be a pioneer. For example, Churchill understood that to advance against machine gun fire, you should carry a plate of steel, and it’s not convenient to carry it in your hands. It’s heavy. You need to have a vehicle — the tank. He’s the one who understood that you cannot outpace the rate of fire of a machine gun.

When radar came along, he understood that radar should be used to have a defense perimeter. The Germans never understood that. The Germans used radars for individual dual engagements. He understood the most important thing is to have a perimeter so that you know where they’re coming, so you can make a rational use of your own fighters and not spread them around.

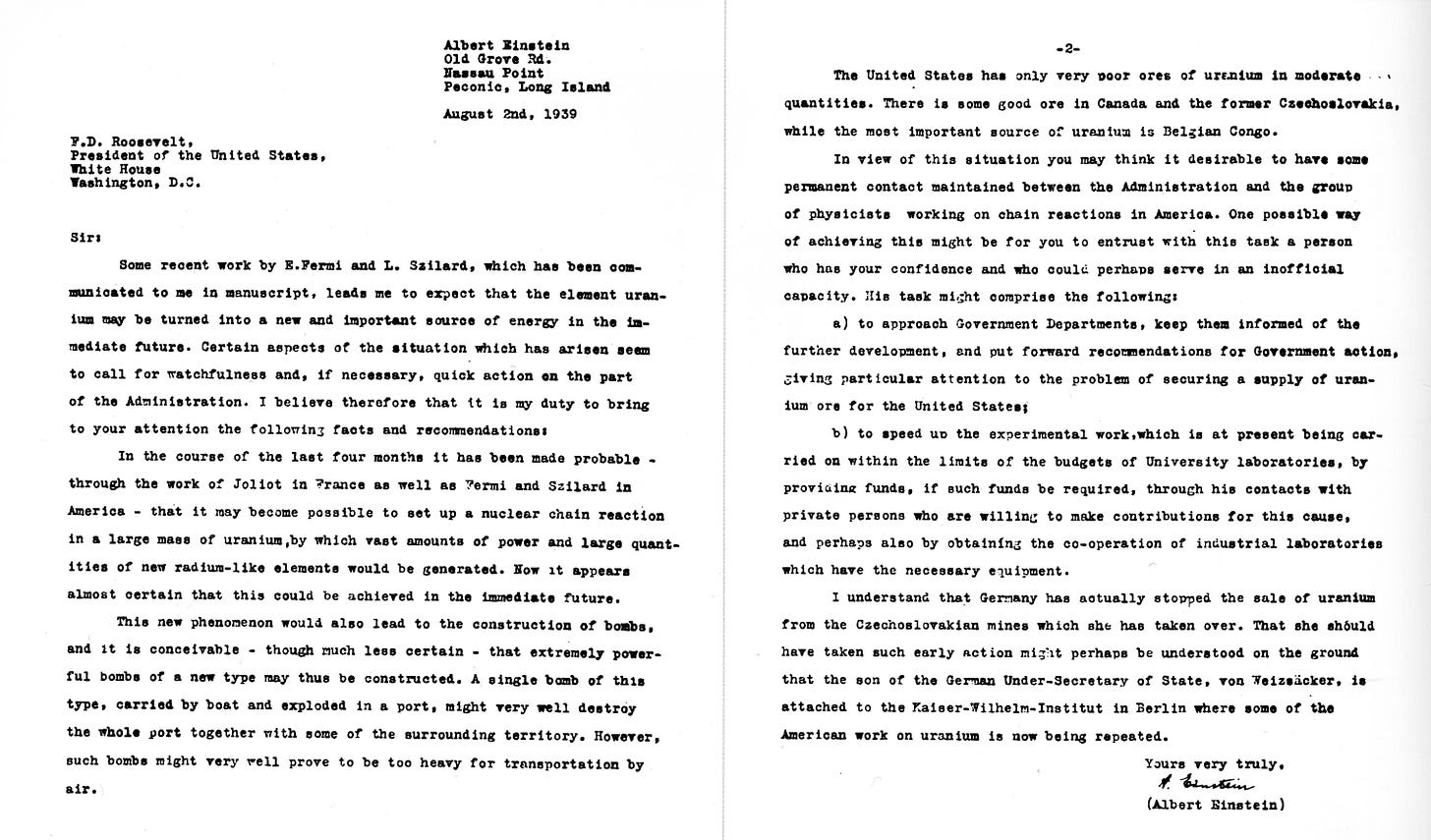

Then, and this is important, when the nuclear weapon comes along, because some refugee mathematicians contradict the prevailing opinion that fission bombs are impossible, which was uniformly held by the leader of the profession in the United States, Enrico Fermi, who believed the bomb was impossible. Joliot-Curie in France, son of Marie Curie, believed it was impossible. Eisenberg in Germany believed it was impossible.

The dissenting people were a bunch of refugee scientists, three Hungarians who were in the United States, Teller, Wigner, and Szilárd, all products of the same school room, the class in Budapest. The legend is that these three guys went to Einstein. Einstein wrote a letter to Roosevelt. Hey, presto, Manhattan Project. The letter was put in a safe.

The actual way it started was in England, because Churchill was the chairman of the radar committee, so to speak. Every physicist had access to him. Every professor. The two guys who did the same calculations as Wigner did, Teller and Szilárd, they reached Professor Oldfield, who was an Australian at Birmingham University — he went to Churchill. Churchill is the one who actually initiated.

The same guy who never finished school, who never went to secondary school, charged Omdurman with a sword in his hand, is the guy who made the tank, and then made radar and nuclear weapons. Why? Because he understood something. He really had this sense for the realities of these things.

As I say, I became interested in war at a fairly young age.

This was a deep interest in war, and also always actually a technology interest. My last book is all about technology, but always interesting technology of war. Now, Churchill did it all by innate talent of some mysterious kind. He was not well educated. On the other hand, I didn’t have to do that. I was well educated. I had wonderful schools.

When I had to leave boarding school because I turned 16 and I discovered girls, I abandoned boarding school and went to London by myself. My parents disapproved. They said, “Either go back to Milano, Italy, or stay in boarding school. A 15-year-old kid can’t run around London.” Well, I rebelled and I earned my own living.

When I went to the local public school — state school, not public school, it was a grammar school. They no longer exist in England. They’ve been abolished in the name of equality, in the name of diversity, what you call equity. Grammar school meant that you were doing advanced-level exams.

In my school, there were six or seven boys in a class. Our history teacher was L.C.B. Seaman, who wrote a book, From Vienna to Versailles, that was used in every university to teach first-year students at university. It was Vienna to Versailles, 1850 to 1920.

Again, blind luck to be in a school, not in Milano, but in Palermo, where a disciplined teacher gets away with teaching the language is not — Instead of not teaching Italian, teaching Latin. Then, blind luck to have landed in a boarding school in England, where you had these refugee professors from Germany who were great men, basically, great men teaching kids. Several of them deserve a biography, actually.

All good luck and everything else. Then, it went on, because I never actually started a career of any sort. I was an oil consultant in London. Very well paid, actually, because I got the job — I was flying to Paris. I had a girlfriend in Paris, so I used to fly from London to Paris. The only way I could afford it was the overnight mail flight. You paid £10 for the flight, which was money, but not huge money. One day, instead of other scruffy people like myself, next to me, there was a guy wearing a three-piece suit. He was running this very expensive oil consulting firm. The flight was long, two hours or something, because the planes were not that fast. He hired me. He hired me right on the flight, “Come to London. Come to see me. You’re going to work for me.”

What was the work? Middle East political advice for oil companies like Shell, British petroleum and others. What was the problem? Turmoil and coups. I went to Beirut, and I interviewed the people who were being overthrown from Syria, the Chief of Intelligence, wondering, going to the cafe with everybody else. I wrote my first coup book on that basis. I wrote it by interviewing these people on how they made coups. My book was called Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook, a provocative title.

My book is a practical handbook on coup d’état, and it starts with the phrase, “Overthrowing governments is not easy.” It’s written from the perspective of somebody who’s planning a coup, not a description of how this or that coup was planned.

The book was born because I met a man called Oliver Caldecott in a pub. He was an editor at Penguin Books, and he says, “Well, what about writing a book?” I said, “What do you mean a book?” I had no intention or idea or conception of writing a book. But he more or less said, “You have to write a book.”

I was thinking I could write a handbook on coup d’état. He gave me a contract. He gave me the money. I spent the money. Now, I was obliged to write a book. I had very little time. I had the typewriter, Lettera 22, a mechanical typewriter, tik, tik, tik. I wrote the book very fast after work, because I had this oil consulting job, which was a fantastic piece of luck.

Then, the book captured me. I started writing as a lark, really. Then, by starting that particular way, “Overthrowing governments is not easy.” The first thing, I got carried away with it, and that’s how I wrote the book.

Now, Penguin itself, the editor, Oliver Caldecott, was also an extraordinary fellow. He was very enthusiastic, and he successfully sold it to something like 15 different foreign languages right away, including Germany and France. Of course, the German publisher invited me to Germany and all kinds of things, and then in France. I was in Paris when the book was published.

In 1968, there was a revolution in Paris. I was so enthusiastic about Paris and a particular lady I met that I stayed in France. I basically left London and lived in Paris, except there was the June 1967 War. There was a buildup before that war. It wasn’t a southern war like 1973 that was out of the blue. There was a buildup. I went to Israel. I went to the upper gallery. I was put in a local defense. I claimed my British credentials with these old weapons I’d used. The local defense used those old weapons. The Israeli regular army had the Belgian FN rifle, which was a new type of 762 mm rifle. Later, they had British Lee-Enfield rifles, the very ones that I’ve been trained on from age 13. They had Bren guns, the light machine gun with the recur magazine, which was our machine gun. The weapons were totally familiar to me. I greatly enjoyed that war, I have to say, because it ended rather gloriously. Went up to the Golan Heights. I was not in the first echelon, the second, the third or the fourth. I was with the tag-along looters, whatever you call it.

The first echelon suffered casualties. It was a heroic fight. I saw it all because the Golan Heights are so steep that, standing at the bottom, you see everything. I certainly was not fighting heroically. That was the war. I left my job in London to go there. They didn’t fire me or anything. The war didn’t last long.

That was the first time that I was in combat. I discovered that a lot of things that I thought about combat were wrong — for example, that you have to be brave. You don’t have to be brave. You don’t. I was never in a cavalry charge like Churchill was, who gets on a horse and charges against the enemy who was shooting at you.

I didn’t go up to the Golan Heights. I wasn’t first echelon. I was just a rear guard. The only thing I had to do was to repel attacks. There were a couple of Syrian attacks, nothing very elaborate. A few tanks with some infantrymen working alongside them, very old-fashioned, minimal. You shoot at them. I didn’t see anybody being afraid. I wasn’t afraid. That was my first introduction to it.

Actually, the Six-Day War, everything was wonderful about it, except that it ended very quickly, just when you were really enjoying it. The ‘73 war was better. I was a volunteer for that one as well. I didn’t go there before as I did in 1967. There was a crisis buildup, and I got there before. This one, I arrived on the second day or even the third day, possibly.

I was milling around with somebody, a former army general, who had been an attaché in Washington. Became an army general, organized a whole new army division by pairing odds and ends of people with captured Soviet armored cars, eight wheelers, troop carriers, and tanks. He created a division out of nothing. The equivalent of a division, it was all missing pieces and so on. We crossed the Suez Canal. I crossed the Suez Canal and ranged in the rear battlefield and so on.

As I say, I don’t think I was ever in serious combat. Not at all, but I was simply moving around — I was present in a battlefield where things could have happened, but I’ve never actually experienced it, neither then nor later when I was a contractor in Latin America and so on. I never actually experienced this question where, “Oh, I must be brave.”

In other words, I was never in the First World War. I never experienced that of being in a trench in the First World War and people blow the whistle and you’re supposed to abandon the protection of the earth in front of you to jump up, face the enemy, fire machine guns, trade bullets and so on. I never experienced that.

I was in combat in many different places. I was actually in the British army. They deployed us at one point to Borneo, no less. I was never in a situation where, in order to be a soldier, to be there, you had to expose yourself to murderous, lethal, intense fire, that kind of stuff. I just never experienced that. I have no idea how to react.

In Borneo, we were very few, and the enemy was even fewer — there was a jungle and so on. The British army, at its best, because the British army was at the time, as I learned much later, operating a whole jungle school in Johor, Malaysia, where even American officers went later on when the Vietnam war stopped. Only the British army had the jungle school.

When we ended up in North Borneo, I asked the lieutenant colonel in charge of the battalion, I said, “Where are the jungle specialists who tell us what to eat and what to wear and how to do this?” “Oh,” he said, “Naturally, they’re all in Germany, in the British Army or the Rhine. The whole command doesn’t have a single one.” I said, “Are you bringing them back?” He says, “Well, the ‘War House’ keeps promising one,” that’s how they call the War Office, the Ministry of War. We had to improvise everything.

The British army always goes to war completely unprepared. In the end, it wins because it doesn’t break apart. We were sent there with woolen uniforms suitable for Germany. The British army was focused on Germany. We had woolen uniforms that you couldn’t wear, so we had to basically strip, go around with underwear, because in the jungle, you would just die. Our rations were heavily on corned beef. As I’m sure you know, in tropical conditions, if you eat corned beef for a month, you will never recover from the gastric complications that this causes in tropical conditions and so on.

Our rations were wrong, and our weapons were completely wrong, because the Borneo jungle is very thick, very dense. Our rifles were very long. Our rifles was called the SLME, the short Lee-Enfield. They called it short because it was so damn long, and you couldn’t swing it around in the jungle.

I never experienced that kind of war, where you are standing in a trench and they’re going to tell you to go over the top of the trench to face gunfire.

The Iliad and Revolutions in Military Affairs

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned your interest in the interaction between technological change and warfare. Could you pick a few examples from history, and explain how they illustrate the dynamics, how technology ends up changing the way it happened?

Edward Luttwak: Small arms, as you know, arrive as arquebuses, with a very low rate of fire and then they get better rate of fire. Then right through, as Europe evolves and modernizes, you have soldiers that are regimented — they advance in files and lines. They have to advance against artillery, they have to advance against muskets and so on. Then, a whole culture of uniforms, of martial music, band music, a whole culture of bravery against fire is what enables war to continue once firearms arrive.

Jordan Schneider: Right, because if not, who would do this?

Edward Luttwak: When the firearms arrived in Japan — and they arrived and very quickly and were used very well — the response of this society was to stop war and to have the shogunate that suppressed all war. The samurai culture continued, but it was devoid of actual consummation, so to speak, because the shogun stopped the war. Why? Because the Japanese social structure could not survive the firearms.

In Europe, they didn’t stop war. Indeed, social structure continued to be smashed by firearms. Finally, we reached the invention by the very important American Hiram Maxim [the automatic machine gun]. Suddenly, by being able to fire 550 rounds per minute of belts of 50 rounds, the entire culture of Europe — or the war culture of infantrymen, drilled and disciplined to advance against fire, that is, against the peppering of muskets — becomes irrelevant.

Of course, they tried at the beginning of the First World War. The massacres take place in battle — 10,000 dead here, 20,000 dead there — to achieve no advance of ten yards or something. Technology intervenes in war, incrementally and invisibly, changing nothing.

Then, suddenly, technology intervenes and changes everything. It ended the possibility of the cavalry charge. Cavalry gets swept off the battlefield.

Finally, there is technology, the tank. If the machine gun fired small arms ammunition and a piece of steel stops it, and now you find a way of bringing the steel forward, because somebody else, unrelatedly before the war, had invented the agricultural tractor with tracts and an engine to be able to pull plows in thick terrain.

Technology arrives abruptly to take you out of a bind, in effect. The First World War would have been a complete stalemate were it not for the tank. The tank broke the stalemate. A single invention. Technology intervenes abruptly. When it does, the ability to change everything, to make the strong weak and the weak strong.

Jordan Schneider: What books come to mind that illustrate the interaction between technology and warfare?

Edward Luttwak: The poet, Robert Graves, wrote his memoirs, Goodbye to All That, where he gives a detailed description of fighting in the First World War, and I learned enormously. The poet, Robert Graves, had the poetical education from a young age. He was conscripted for the First World War. All his friends, like Siegfried Sassoon, were all anti-war people, but quite a few of them were heroic fighters.

Graves, who came in as a second lieutenant because he was upper class, ended the war with no particular ambition. He ended the war as de facto brigade commander. He writes about the First World War, Goodbye to All That, in great detail with the perspicacity of a literary man, of a poet. A great poet, I think. I learned a lot from that book about the essence of a lot of war. He writes in detail. He writes about tactical things and how command works. I learned a lot from that book written by a poet. Not by a retired soldier.

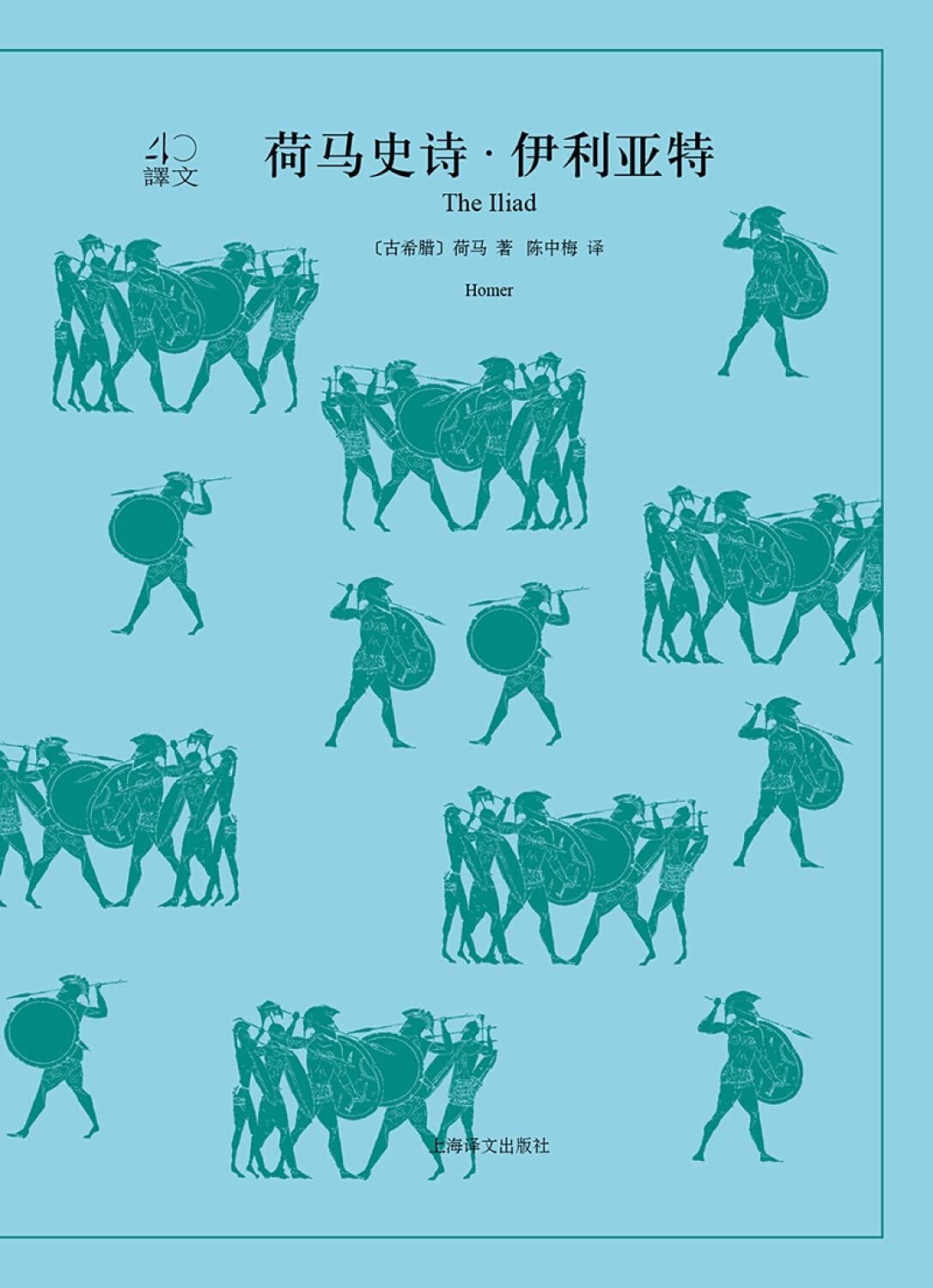

Of all the books in this room — and this room is full of books — there are two books that are dominantly important from my understanding of war. One is the Iliad, and I have 10 different editions because people ask me to review them.

The other is the British official history of the strategic bombing offensive. The official book on the British strategic bombing offensive, by itself, is worth three-quarters of the books in this room put together. In the official history of the British bombing, what you get is the fact that war is actually a reaction. The British bombers were going through, and then the Germans would find a new tactic, which they would then figure out how to circumvent and so on.

The important part is when the Royal Air Force finally finds a way to actually fly to Germany and not to get shot down totally and to be able to find the targets. Originally, they didn’t even think about how to find targets, or to even locate the city.

Finally, the Royal Air Force was able to actually generate as many as 1,000 bombers to actually fly to a German city and destroy the core of it. The traditional German cities were built of wood. They learned how to produce aircraft rationally, as the Germans really never did, by focusing on one model and resisting the temptation to interrupt, to go to a slightly better model, to maintain rhythm and production. They learned how to train people to fly bombers. Each bomber took 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 crewmen and so on.

They come around to Churchill and say, “Look, we can destroy a German city every night that we bomb. We can bomb once every three or four days. If the British industry produces 1,000 bombers a month, we will be able to bomb all the German cities, and Germany will surrender.” They basically say, “Stand down the Royal Navy, forget about the army (which is doing nothing except in North Africa), give us all the resources and we can win the war by bombing.”

Churchill replies, “In war, everything is moving at the same time. You’re successful in bombing Germany. That’s why the Germans are going to pull more resources into anti-aircraft guns. They’re going to put more resources into radar. Right now, you’re winning the radar war. British countermeasures are defeating German radar. If you defeat German radar and you’re able to destroy German cities, the Germans will switch efforts, and everything moves at the same time, back and forth.”

These are the whole basic dynamics of what becomes the logic of war. Action, reaction, the paradoxical outcomes. The very successful missile. You have three missiles, anti-aircraft missiles. One is super successful. The enemy focuses on countermeasuring the super successful, so the less successful missile is still able to shoot down airplanes, even when the best missile can no longer because of countermeasures.

All of this comes in this book on the strategic bombing offensive against Germany. In the broad sense, it was bombers and so on. Also, how Germany responds to bombing through dispersal, removing the targets and so on, so that the power of bombing is so great that it changes the world as the world reacts to this power and outmaneuvers it by evading it and so on and so forth.

As soon as I read the British Bombing Offensive into Germany, I rushed back to my Clausewitz, who was sitting out there looking at me, in order to read Clausewitz’s mountain warfare. Clausewitz is very famous. Many people read the first few pages or a chapter or two, and then they drop it. Actually, there’s a reason — it’s very hard to read. It gets really uninteresting very fast. What they really should do is to ignore all of Clausewitz except for his section on mountain warfare.

Jordan Schneider: Why is that?

Edward Luttwak: He says to you, “Well, in mountain warfare, if you can really put your troops on a peak, on the mountain peak, they will tactically be able to repel any attack.” They’re so terribly strong. That is only true tactically. On that mountain peak, nobody can dislodge them. The enemy is not making war to capture a mountain peak. It is to capture your country.

If you put troops on a mountain peak, they dominate tactically because nobody can dislodge them. But if the army happens not go past that peak and goes two valleys down, they are unable to do anything about it, because they can’t get off the mountain peak and quickly go and do a flank attack. Tactically strong, operationally weak. Operationally is how you win the battle.

Now, let’s assume that your operation is strong, and you concentrate your forces and you achieve surprise, you’re very dynamic in all that stuff, you still are not able to overcome what you meet, not at the operational level, tanks, artillery, fighting each other, but at the theater level where geography comes into it. You can have the experience of the Germans, who won almost every battle in World War II and lost the war because they could not transcend operational victory to achieve theater victory, albeit for different reasons.

For example, Rommel outmaneuvered the British and all that. Actually, you could not conquer Egypt from the starting point, which is Libya, because you could not bring supplies from Libya to an army fighting in Egypt, because it’s 1,200 kilometers of road and you don’t have enough trucks to do it. If you had enough trucks, you wouldn’t have petroleum for them. By the way, they’re so exiguous that a British empire could opportunistically attack those long, long columns, or whenever there was less anti-aircraft, very effectively. Tactical victory is overcome by operational victory, and operational victory is overcome by things like theater strategy.

Of course, in the Ukraine war, we see a simple fact. Ukrainian forces can be very heroic, but they can’t get to Moscow and force them into the war by pointing the sword at Putin’s neck. They can’t get to Moscow. Theater strategy. The Russians themselves were undone by their mistake in attacking Ukraine, which was that their concept of war was much too modern for their circumstances.

General Gerasimov, who is still there, to my great surprise, I would have fired him the next day. Gerasimov is a very modern guy. He believes that you win a war politically. Cyber war. The internet, manipulation of images, and so on forth. He gives a long list of things. At the end, he mentions he forgot about the infantry, the artillery and armor. They did a fantastic ultramodern coup de main. Helicopters arrive and drop a handful of paratroopers who seize the airstrip, then you fly in the airborne infantry. The infantry was delivered by Ilyushin transport. Then, you match up with some vehicles that have sneaked in and descended from Belarus, rush into Kiev, you take over the defense ministry, and you do a coup de main as it’s called militarily, but it’s actually a coup d’etat.

Now, you’ve taken Kiev, and now you have thousands of tanks waiting in long, long, long lines to go through Kiev in order to generate images of overwhelming strength. This is Gerasimov, how you would win the war psychologically, politically, and historically. You forgot about the infantry and all that. The tanks parade through.

When the coup de main failed, and tanks were strung out in the one column, it was very embarrassing that they turned around. Some weapons arrived in Ukraine. Some of the most useful, the Norwegians had 5,000 LAVs, light anti-tank weapons, the simplest, lightest thing. It’s a plastic tube that has an anti-tank rocket in it. You pull out the tube, you aim roughly, you pull the trigger, and it goes off. These Russian tanks were finally hit.

In other words, just the opening of the war tells you all the different ways in which it could go wrong in war. The Russian plan was ultramodern, and the head of the general staff was an ultramodern person. He wasn’t an old-fashioned, stupid idiot who believed in infantry, artillery, and armor. No, it’s all this psychology, and shock, and trauma, and surprise. Very, very clever. That is one way you can fail in war.

The newest way you fail in war is that you don’t understand the levels of war, which are very contradictory. We just had an example. Hamas did a brilliant assault, and actually caught Israelis by surprise. Israelis are very easily caught by surprise. In October 1973, when 20,000 Egyptian troops of the very first echelon, there were 200,000 behind them, arrived at the Suez Canal in October 1973 surprise war, there were 411 Israelis. They are self-confident, they are overconfident.

The other thing is this — the Egyptian army was deployed in front of the Suez Canal. If you allow the enemy to deploy on your front door, he will always catch you by surprise, because all he has to do is make noises as he attacks and immediately reinforce. When you reinforce, he doesn’t attack. Then, waits for a few more weeks, and then he makes noise, and you reinforce and he doesn’t attack. The third time, you don’t reinforce, and that’s when he attacks.

That Egyptians did very well at the beginning in taking the Suez Canal and everything else. By the way, they had 22 positions, the Israelis did, along Suez Canal. Only one of them was fully manned. With how many soldiers? 30. They never took it. They had built this very clever fortress. All you needed was 30 men. Then, in the course of the years, nothing happens. They didn’t have 30 men.

The dynamic flow for war, you read the official history of bombing in World War II, and how the British won. Then, the Germans say, “Oh, they’re serious. They’re bombing us.” They shift resources. Then, the Germans win. It goes back and forth, back and forth. Hamburg, everybody knows that in August 1943, Hamburg, mostly built of wood, was attacked by the Royal Air Force and the US Air Force. That was the first time the British bomber command could send 1,000 bombers, and the US Air Force added its bit in daylight.

Hamburg burns. Burns. The asphalt melts, and the place becomes hell. Hamburgers walk out of their city in all directions. The Nazi Party begins its transformation into a social welfare organization quite effectively. That is when the Royal Air Force tells Churchill, “We can win this war. We’ll just stand down the useless army and navy. We’ll bomb Hamburg.” Churchill was smart enough to say, “No, because your very success of last night condemns you to failure.”

In fact, after Hamburg, there wasn’t a triumphal barge for German cities, but greater and greater and greater losses and so on. Flying in Bomber Command in World War II was more dangerous than being an infantryman in the First World War.

Jordan Schneider: The chapters you did about the air war in Europe were the ones that unlocked it for me, because you really do see every level of war and the interaction between them, from the tactical stuff.

Edward Luttwak: Where did you read that? In The Logic of War & Peace?

Jordan Schneider: Yes. You get something tactically right — “Okay, if we find the four factories that make the ball bearings and we blow them up, then all of a sudden, they’re going to go back to donkeys.”

You just alluded to it right there. The success of it led to them adapting from an anti-aircraft perspective — they spread out the factories, and you end up changing the psychology of the whole regime. I’ve watched these really weird movies made in Nazi Germany in 1942, and they’re walking around on the street and going to the plays or whatever. Then, you’re in total war mode, because the city gets bombed, it’s much easier to get people to make the sacrifices they have to.

Edward Luttwak: It took really a long time to get to that point. Then, it finally evolved. The British official history of the bombing offensive against Germany, written by a guy called Noble Frankland, which is up there, that is what got me going. It contains some fantastic documents in it. One of them is the report of the police minister, the police president of Hamburg, of the bombing, which is the first description of the meltdown effect. The fire starts that attracts, sucks in air with this tornado, with high hurricane speed of the flame going up, hurricane speed, people get blown off their feet into the molten asphalt on the roads and so on.

He wrote the description. Unknowingly, he wrote it immediately afterwards, and his text in English translation in that book is a literary masterpiece.

There is a lot of good literature. War generates a lot of good literature because people are forced to think about things. War makes you think things. I consider the Iliad as the foundation document of Western civilization, whose impact on life and society was only mildly moderated by the advent of Christianity and so on. The Iliad is about the essence of work. As I say, I read the Iliad 12 times, only for the purposes of writing reviews of new translations, which I was duty-bound to read the new translations. Some of them were awful.

My most important article ever is called “Homer, Inc.” It’s available free online. It’s a description of how the Iliad was written, how it was edited, why it has the power it has, and why all the Western countries are still very interested in it. There are multiple translations, and a new one comes out every two or three years.

In India, where the British set up classics departments in all the different universities, like Madras, Bombay, and so on, nobody knows Greek. Nobody’s interested. We couldn’t sell a copy of the Iliad for nothing. The Arab world absolutely rejects it. The only Iliad available is a very late and very bad translation. Where is their enthusiasm for the Iliad?

Japan has studied it, definitely from an early point, when they modernized, when they decided to go western, they were sensible enough to understand where it started from. They didn’t try to jump into petroleum engineering without starting with Homer.

The big place is China. The Chinese are enthusiastic about it. When I wrote this article, “Homer, Inc,” there were four different translations of the Iliad in China already. Since then, several more appeared. They’re not produced by some beautiful academy of ancient history or something. They are produced by commercial publishers out to make money, and the Chinese line up and buy them.

Jordan Schneider: It’s really remarkable how Western classics have such a foothold in China.

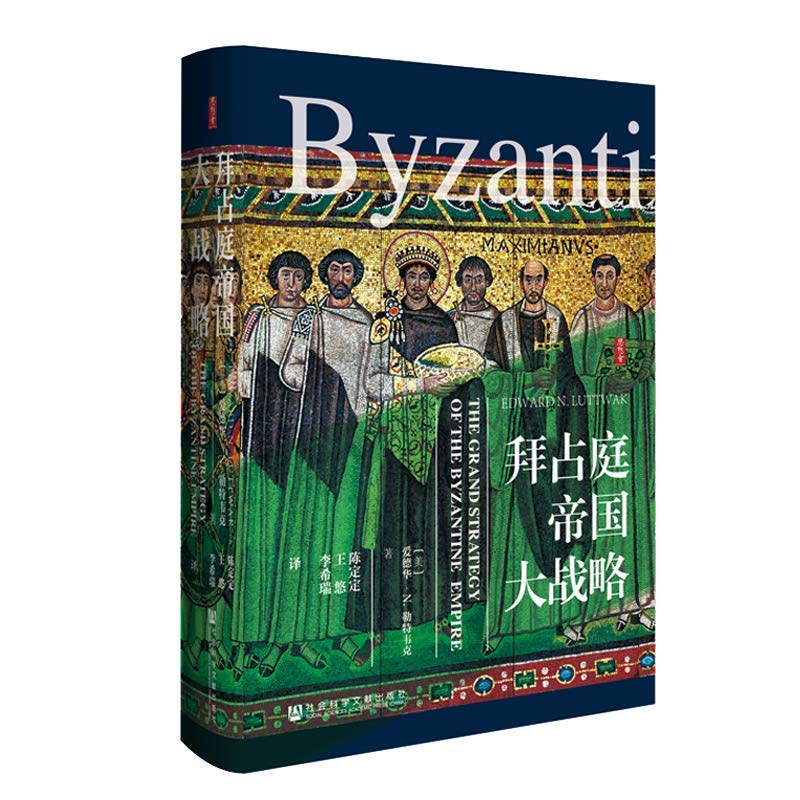

Edward Luttwak: You experienced that in China yourself. It’s a foothold, and it’s a serious one. My Byzantine book, which has been published in different languages, Greek, Turkish, Italian, French, and so on — Harvard Press itself did a beautiful edition, I have to say, a gorgeous edition with the Romano mosaic covers and all that. The most beautiful edition is the one published by the Communist Party of China, the so-called Academy of Social Sciences, which is actually the research bureau of the Communist Party Central Committee and Politburo in Beijing. It’s called the Academy of Social Sciences.

Their publication is magnificent, the most beautiful edition. I give them great credit because it came out years after my book called The Rise of China vs. the Logic of Strategy, which is the book that says that China will fail. Even though I published a book saying that the Chinese are wrong, they would fail, they don’t understand, they published the Byzantine book. It’s magnificent.

Before that, they did not know anything that it was against their system. I first visited China when Mao was still alive. I was there when he died. I was actually one of the honored guests at the funeral in 1976.

Removing War from Europe

Jordan Schneider: Come back to the pitch for reading Homer. What can you learn in there that you can’t learn anywhere else?

Edward Luttwak: If you read the Iliad carefully, you realize that the Iliad presents a superman, because remember who the hero of the Iliad is, Achilles. Achilles is somebody who feels sorry for the Gods, because the Gods are immortal. Therefore, they can never be brave. Therefore, they can never impose their personality onto the universe, because they can do any foolery they want. In fact, there’s a chapter in the Iliad about when the Gods start fighting, and it’s a comedy. It’s ridiculous. They can’t die, so what’s the point?

First of all, it’s the only book that gives man his full dignity, because man is not afraid of death. Being guaranteed against death means that you can never be brave. If you can never be brave, you can never be fully achieved. You are superior to God, because you’re not immortal.

The Iliad teaches you really what bravery is about, and how life would be truly tragic if you were in the position of a Greek God. Because the Greek God cannot die, he cannot be brave. Therefore, he cannot be fully achieved. Everything he does is foolery and pointless. Whenever a Greek God feels like having sex, he can just transform himself into an eagle and pick up a girl or a boy, as the case might be, as Zeus did for Ganymede himself, and you can have your way. You can do anything you want. Therefore, none of it means anything.

That’s what you learn from the Iliad, which is — human being, don’t complain. Assert yourself. Make yourself realize yourself. That’s what counts. That’s the ideology of it.

Then, of course, it has all these different characters in it. For me personally, one of my great happy moments is I discovered from the translation of the correspondence, the Hittite correspondence. Troy was under the sovereignty of the Hittite empire. When they found the correspondence of the Hittite empire, they found a series of letters about Troy. They were found in the 1930s, and translated and made available belatedly in the 1950s, that’s when the Trojan War went from literature to history. You have there the figure of Alexander, also known as Paris, the one who provoked it all, and you also have Achilles.

His Hittite translator’s name is really bizarre, but the Hittite ruler is writing to Agamemnon and saying, “I understand you have a war against Troy. Troy is really a protector of the man, but I know they caused the war. But as for this other guy, Achilles, he raids my towns without any reason at all. This has nothing to do with your war. He’s supposed to be besieging Troy, and there he’s going off raiding.” Achilles grabs the daughter of this priest and so on, and then rapes her, and then he falls in love with her.

Then when they want to take her away, this is the daughter of the priest, and give her to Agamemnon, which starts the whole machinery of the story, because he doesn’t write in Iliad how the war began. It’s the 10th year of the war, and there’s this episode, not between Greeks and Trojans, but Achilles as a Greek prince was falling against the great Agamemnon, who is obliged to give up the girl he captured, because she’s the daughter of a priest of Apollo. Therefore, Apollo was attacking the camp with his arrows, and that’s why they were dying of plague and so on.

He has to return his girl. Achilles refuses to fight. He goes to his tent and says, “Even though I captured her with my spear, I won her with my spear, I’m truly in love with her. I really love her. He took away this woman I really love.” Suddenly, we realize that war was not yet a collective thing. Inherently, it was voluntary. That opens the door to something very important.

Most wars of history have been fought by volunteers. If not by actual volunteers, there are some regiments that were called to war, and people rushed to war. On October 7th, Israel was caught by surprise. On October 8th, they started issuing notices to reservists.

By October 10th, a problem built up in the Israeli army, because they had recalled reservists to the units they belonged to, which were reserve formations with all the workers, but whose commanders and so on would arrive from active duty, full-time jobs. Then, the soldiers arrive from their homes and they go to a depot. In the depot, they pick up their uniforms, their weapons, their vehicles, and roll out.

They discovered within two days of the recall that many more people had shown up, people they didn’t call. Let’s say, in this battalion, there were 400. Of the 400 reserves, there were 520 reserves in the book. They didn’t call the others because they were older, or because they were marked as having some medical issues at some point. These people who were not called up, all went anyway. They showed up anyway. This is a wonderful thing. You call 100 soldiers, and you get 120. Isn’t it wonderful?

Except that if that happens at the company level, two levels, up at the brigade level, they think they’ve got 100 soldiers in that company, but it’s not. It’s 130. They send trucks for 100, and the other gets stranded. After a while, they started issuing public notices, the police, “Don’t come. Don’t come. Don’t come unless you’ve really been called.” Then in some cases, they had to call the military police to weed out people, because they’re all there with friends, and they were covering up for each other. That is a reservist being called, you call 100, you get 120.

What happened more often in war, they didn’t have a system, that’s peculiar to the Israeli army, is that wars were fought by volunteers. People went to the colors, they volunteered to fight. The two World Wars were great anomalies when giant state bureaucracies compelled a lot of people, including very reluctant people, to go to war. Historically, wars were fought by volunteers who wanted to go to war.

The Iliad tells you why you want to go to war. Heroic achievements, the fun of it, the excitement of it, and all the rest of it. If war were not so much fun, there wouldn’t have been so many wars, because most wars were fought by volunteers. In the Civil War, there were draft riots in New York because people didn’t want to fight. That was because America was very early in conscription. Conscription, forcing people to fight, is very new. In human history, it’s a very recent development, from which there’s been a withdrawal.

Now, this brings me to a very important thing that is a tragedy on a continental scale. The energy of Europe, the dynamism of Europe, the whole thing that came out in art and science and everything else, is such that when Europeans got to that historical stage, they spilled out on the whole planet. Small numbers of Europeans conquered Latin America, conquered Africa, and conquered much of Asia. Why? Because they were forged by Europe. The intense competition between rival states that competed even more because they shared a common culture to a large extent.

Every little state was competing with every other state that generated dynamic energy. Europe was like a veritable nuclear reactor of energy from the collision of all. Florence fighting against Venice and Siena against Florence, Milano against — and then, Italy against France. This war was the engine of European growth. That’s why the Iliad was the actual constitution of Europe, not the New Testament. It was the Iliad.

The Iliad is the constitution of Europe. All these little European statelets were competing against each other. There were perpetual wars. Every war destroyed buildings. After the war, they built twice as much. The warriors went to war. They loved war because they were all — 99% were volunteers. Until you get really to the first 19th century, really, late 19th century, you get volunteers.

Men love war. Women love warriors. Instead of the population going down, as soon as the war ended, the warriors would come back, women would jump on the warriors and vice versa and make children. From war to war, Europe’s population increased. Europe was a land of children. Every time there was a war, there’d be more children. And then, there’s more reconstruction.

Now, somebody had this idea of removing war from Europe. There were problems with war by 1945. Not only the fact that the Second World War was really horrific, more than any other war, really, but also, the advent of nuclear weapons made it seem a bit pointless. There was definitely a problem. There was exhaustion. The exhaustion of 1945 is a simple, normal exhaustion that you had after every war for 2,000 years. Then, there was the nuclear fact as an intellectual fact somewhere out there. Then, there was the fact that the war was particularly horrific.

It was long. It was long, ‘39 to ‘45, long and horrific and a lot of disappointments. There was a lot of really huge destruction and so on, killing and many more people died and so on.

Europe gives up war and you say, “Oh, wonderful, there’s no war.” What they did was they removed the engine of the car. Because, since you remove war from Europe, there are a number of other things happening. First, Europeans stop making children. The most pacifist societies, Spain and Italy, make the fewest children. There are more veterinarians than pediatricians in Northern Italy. There’re not children, actually, and there’s no dynamic energy. All of it is gone.

War was a machine. It was the intense competition between all the different European states and statelets, by putting them all in a union together where they can’t fight each other, the armies, navies, and air forces remain as ritualistic things. They have no real combat capability. The Royal Air Force recently flew to Cyprus, and from Cyprus to Yemen, and dropped bombs.

There are air forces in other countries, and they have generals and airplanes, but they can’t do it. If the Italian air force were ordered to bomb Yemen the way the Royal Air Force would, they would have a big advantage, because the Italian air bases are much closer to Yemen than the UK. The order would never be issued.

Right now, Italy has a right-wing government, or at least center-right. What Prime Minister Meloni puts on a tweet is a celebration because the big Italian warship, the Vulcano, a very big ship, came back from El Arish carrying some Palestinian children who need medical care. Whereas the Italian ports are in distress because traffic is interdicted in the Red Sea, which means that Italy is bypassed. This affects the Italian economy powerfully.

The Italian Navy is the largest in the Mediterranean. She does not send it into the Red Sea to defend traffic to save the Italian economy. Instead, she sails a ship to El Arish to pick up some Palestinian kids. Why? Because even the center-right government, in fact, neo-fascist or whatever she is, has decided that war is no longer admissible. In fact, they have sent one frigate to the Red Sea, but not as part of the US Anglo-American Operation Prosperity Guardian, but separately as a European mission with the Germans or whatever. Not only are they not attacking the Houthis, of course, but they’re not even intercepting Houthi missiles, unless they aimed at themselves.

You can divide nations into two categories. Three, actually. One is countries for which war is irrelevant. Like Nauru, for example. 1,000 people in the Pacific with no enemies who can reach them. War for them does not exist. It would be absurd to bring a war philosophy to Nauru in the Pacific. For everybody else, I use the very ancient Latin concept that only I use, which is capax belli. Capax, capable of war. Bellum, of course, is war. Genitive is belli, capax belli.

If you go and research and try to look for the original quotation of it, you won’t find it, because I invented capax belli. It’s an ancient Roman concept that happens to have been invented in Maryland, by me. It is a useful concept. Countries capable of work and those that are not. The British spend a lot of money on the Royal Air Force, but the Royal Air Force is capable of war. It just flew to Cyprus and Yemen and dropped bombs.

The other air forces in Europe also cost a lot of money. They’re also expensive, but they’re not capable of war, because either the political level cannot issue such orders, or they go against the spirit of the age, as they would put it. All because the pilots didn’t really sign up to really fight, “What? I’m supposed to be flying over Yemen? What happens if I get shot down? I’ll be taken by tribesmen who will tear me to pieces.”

There’s no enthusiasm. I don’t see protesting airmen all over Europe saying, “How come we are not helping to fight the Houthis as well? I’m a fighter bomber. Why don’t you let me fly on it?” No such thing.

In some cases, like Spain, the Spanish have an air force, they do, and they have combat aircraft, and they’re not cheap. If the Spanish government ordered them to bomb Houthis, they would not do it — there would be a protest. The pilots would walk off.

Once you’re not capax belli, you have lost something that binds your country, makes the country effective as a country and makes military institutions valid. If you are not capable of war, that doesn’t mean logistics, like you don’t have enough ammo or something, that’s never a problem.

Jordan Schneider: It’s a psychology of political leadership.

Edward Luttwak: The psychology, the culture, the political thing. By the way, right into the military. When Italian soldiers were deployed in Afghanistan, it was essential they should not go into combat. The Taliban were paid off, basically. They paid off the Taliban so they could patrol unmolested. Once you knocked capax belli, you switched off the engine, and you lack dynamism, you lack capability. You can’t do anything else either.

Jordan Schneider: There’s an interesting argument you make in the China book, where you look at Germany in 1890 and you say they had it all. They had the chemical companies. They had the universities. They had the economic dynamism. Had they not wanted to taste the forbidden fruit of national greatness as expressed by hard power in the form of battleships and international colonies, then the 20th century probably wouldn’t have turned out — or the first half at least, wouldn’t have turned out a lot better for Germany.

Edward Luttwak: No, I would say that if Germany had not gone to war in 1914, given the fact that it was more advanced in the chemical industry, metallurgical industry, and had competed with the United States only for the electrical industry, dominated the pharmaceutical industry. Deutsche Bank was the largest bank in the world, the most powerful bank in the world in every possible way. Given the fact that German education had advanced so far beyond anybody else, it wasn’t just universities, you understand, it was a high school. The German Hochschule, which just means high school, was a formidable institution.

If they decided not to go to war in 1914, then Europe would have been compromised in other ways, because Germany would be absolutely the dominant country. That would not be a problem. When I was born, German was the dominant language, even though it was ruled by Romania. All the books were in German.

The fact is, Germany dominated from the pharmaceutical industry to education, to every damn other industry, to the university. Also, the domination was self-enforcing, because the best and brightest would go to German universities. The people of the Manhattan Project were all Hungarian Jews and Polish Jews, whatever they were.

Jordan Schneider: Oppenheimer, famously, of course.

Edward Luttwak: But Oppenheimer was born in America. All these people, most of them were not. They were born all over Europe.

Jordan Schneider: He went to study in Bonn.

Edward Luttwak: Of course, he went to study in Germany, and they went to Germany. The Hungarian bunch were beneficiaries of highly superior secondary education and mathematics teaching in high schools, and Hungary was the world leader in every respect. Russians today, by the way, the Russians, with all the decline of Russia and all the fuck-ups and screw-ups and all the problems they have, even today, Russian high school teachers, mathematicians are superior in their education.

Germany would have been the dominant power. All they had to do was not challenge the Royal Navy, because German commerce worldwide was protected by the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy protected German commerce as German commerce was becoming more and more dominant all over the place. From coffee plantations in Southern Mexico, in Guatemala, to every damn thing you wanted, and traveling the world’s oceans protected free of charge by the Royal Navy. That’s when they decided to challenge the Royal Navy.

In case a comparison comes to mind, the Chinese wanted to challenge the US Navy, which enables them to sell all over the world. Who would do that? Insanity.

Jordan Schneider: This is what I want to bring it back to the Greek tragedy, because you have these two countries, Germany, which is doing everything well. All the trend lines look really great. Then, China in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, is really firing on all cylinders. You have this incredible integration with the global economy. Is there something just about humanity where, when you see power, you have to take it all the way?

Edward Luttwak: One can go beyond that. One can go into a more logical sequence. The wonders of free economies, commerce, the wonders of science and the industry it brings, all of it is just really wonderful, but it’s all based on different kinds of freedoms. Those freedoms are conceded by a state. You have a state that maintains law and order, protects the borders, but it’s a state whose politics, whose matters, whose leaders limit their accumulation of power. They allow you freedom to operate sufficiently so that the economy can flourish and academic universities can flourish.

Then, what happens is that they still have the quest for power, they still have the craving for power, but they manifest it, not by imposing themselves on their own citizens, but they manifest it, for example, in colonial competition or something at the turn of the century or something of the sort.

The problem was that the Germans dominated Europe militarily, but they could not expand militarily. As Bismarck had explained, Germany, with his wonderful army and everything else, had reached the culminating point of success in 1871 when they formed the German Empire. Bismarck understood that if Germany expanded by another square meter, it would start a process of global coalition against Germany and to stop it.

He was blessed by the fact that von Moltke, his chief of imperial staff, fully understood strategy. As soon as Bismarck formed the German Empire in 1871, he was greatly applauded. A week later, people started saying, “Well, the Italians are unifying Italy. All the Italians are coming under the Italian flag. We have Germans in Silesia that are Germans, but then we have Germans there, and we have Germans in Transylvania, as it happens. Mainly, we have the Germans in the south in the Austrian Empire. Now, the Italians have unified, the French have unified. Why the hell can’t we unify?”

Bismarck basically said words to the effect that, “We have reached the maximum culminating point of success. In our lifetime, in the lifetime of our children, Germany cannot expand by one inch. If we expand by one inch, everybody else will gang up against us. Everybody will gang up against us.” He might have said, “Even the Americans,” or something. He understood there is a culminating point of success. Going beyond that doesn’t make you most successful, but you descend the curve of success.

As I say, his luck was von Moltke, the chief of the general staff. It was intellectuals, naturally, professors and so on, who said, “We have the most powerful army in Europe. We have unredeemed Germany, because we have all these Germans who are not in Germany. Everybody else is unifying, the Danes, the Italians, the damned Portuguese. Only we have Germans stranded outside Germany. So, we have to use our power to unify Germany like everybody else. Are we racially inferior that we can’t be unified?” These were very strong arguments. They were not advanced by hotheads in pubs. They were advanced by university professors.

The first place they wanted him to expand was, of course South to Austria and so on. In the Balkans, with the excuse of the Balkans, the Balkans are in turmoil, and he comes up, he says, “All of the Balkans are now worth the bones of one of my grenadiers,” and so on.

He had this very clever guy, von Moltke, the chief of the general staff, who not only understood tactics and operations. He was the one who really understood how to operate the railways. He also understood that tactical victories are worthless. You need operational victories, all these things. He was not a man who wrote books, but he clearly understood all that from his single decisions that he was making like that. He backed him firmly.

The moment that von Moltke is gone, Bismarck is still held up until the young Kaiser comes. The young Kaiser says, “We have to use our power to unify Germany. It’s our duty. We left our fellow citizens stranded. We are sailing in a ship, and we’re leaving them on the shore.”

Then, the intellectuals weighed in. The German tragedy would not have been possible if all the intellectuals had not lined up in support of the idea of building a fleet to challenge Britain. Britain was assuring the commerce of Germany all over the world through the Royal Navy.

What happened is that the British reacted, and they resolved all the quarrels they had with the French. They made 72 concessions and 72 colonial disputes. They satisfied everybody so that the next thing Germany turns around, they find themselves surrounded by two world empires against them.

In the case of China, Xi Jinping is particularly inexcusable and shows his intellectual nullity. For all his pretensions that he knows literature, I trust him that he really is very interested in literature. I’ll give you a small proof of it. Goethe wrote three or four or five times more than Shakespeare. Therefore, there’s no complete Goethe in English. There’s no complete Goethe in French. There is in Chinese. Under Xi Jinping’s order, the Shanghai Foreign Languages University had to mobilize all 85 Chinese Germanists to bring all of Goethe in translation in 87 volumes. It doesn’t exist in English.

I believe he understands literature and loves literature, Xi Jinping. But clearly, he has no understanding of history, because Chinese commerce is carried by the US Navy. The US Navy protects Chinese commerce. For them to oppose the US Navy is the same level of high-grade idiocy.

That’s exactly what Xi Jinping says in China, “We have to challenge the US Navy, because if we don’t, one day, they will suddenly shut down everything.” This is not an ordinary error — I made mistakes. I made them because I’m stupid various times. I made a mistake yesterday. I made a little mistake because of some foolish calculations. You need intellectuals for this. To make that level of error that Germany made in challenging the Royal Navy, beginning the whole competition, causing the British to start organizing a coalition against them — for that you need the intellectuals.

Jordan Schneider: You have this action and reaction, which you saw in Germany and you’re seeing now in China today, where the rising power gets ahead of its skis. All of a sudden, the entire region recognizes the fact and reshapes itself to make sure that power isn’t able to manifest its mission. We have that, but we also have these moments in history where you get leaders who have this sense of temporal claustrophobia, of, “Whatever odds I have today, they’re going to be worse tomorrow.” Then, you have horrible wars start.

Edward Luttwak: There’s also protagonism. Hitler started the war in September 1939 because his health wasn’t great, and he was afraid that he might decline before Germany could fight this necessary war. There were plans to start the war in 1942. He missed out on three years of production or something.

Xi Jinping undoubtedly has this belief that he must rejuvenate China. Paradoxically, China is shrinking and getting older by the minute, because they don’t have babies, but he wants to rejuvenate, and he rejuvenates by fighting and so on. Then, intellectuals provide the rationale that we have to attack the US Navy, because even though our commerce has gone global by the protection of the US Navy, undoubtedly the Americans will not let us really come out on top, so they will abruptly shut down Chinese commerce unless we have defeated, we are in a position to overcome their navy and all that. For that, you need intellectuals.

You need intellectuals to concoct these elaborate explanations of why Germany has to attack the Royal Navy, which was providing the security for its global commerce that was essential to German life, and its growth and so on.

Whenever you see the Chinese navy’s development, and you hear what Xi Jinping says when he visits — the last speech I studied in detail was his visit to the Eastern Theatre Command, it’s the command that has Taiwan, and says, “Most important thing, you have to be ready for war. The most important thing, you have to be ready for war and victory. You have to be ready for war, and I mean real war. You have to be ready for real war and then win a victory.”

He is exhorting them. Exhorting them. Historically, the Chinese never fought. The Chinese were conquered by foreigners. The last foreign dynasty was the Japanese. If the Americans had not defeated Japan in 1945, the Japanese very likely would still be in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, with the nationalists and the Japanese and the communists fighting it out or whatever it is, backed by one or the other.

To make these mistakes, you need intellectuals. Intellectuals mediate. Then, you need the guy who’s afraid that he will die, because his successors are unworthy and only he can achieve this thing. That sets up the timing.

The Chinese are a profoundly unmilitary nation. Profoundly unmilitary. They are not really fighters at all. Therefore, in 1895, a very big Chinese navy with modern German warships was defeated by a small Japanese navy. The Japanese are fighters. The Japanese come from a culture of fighters, but the Chinese do not.

“You cannot deter Persians by killing Arabs.”

Jordan Schneider: What is the right way to conceptualize deterrence?

Edward Luttwak: The right way to conceptualize deterrence is by realizing that everything about deterrence is taking place in the mind of the enemy. You don’t deter by building a missile or by not building a missile, building 4 missiles or 17 missiles or buying this or buying that. You deter by understanding your enemy and understanding what deters him.

For example, right now, the United States periodically attacks the Shia militias to deter them. Actually, they’re just exact agents of the Iranians. Not only do all their weapons come from Iran, but they’re commanded by Iranians. You can’t deter Iran by killing Houthis, because the Persians do not consider Arabs to be people whose life or death is very important.

You cannot deter Persians by killing Arabs. They consider Arabs expendable. Arabs are not much use for anything, so give them a weapon, have them shoot at other people. They’re not Persians. If you want to deter Persians, you have to kill Persians.

That simple proposition doesn’t get through in the White House, because it cuts against the concept that all races are equal, of course, and we would consider Arabs equal. Therefore, the Iranians must consider them equal.

The Shahnameh is the national book of Iran. The Ayatollahs wanted to forbid it, because it’s not Muslim. The guy who wrote it was post-Islamic, but the Shahnameh is a book about Persia, about our Persian kings and Persian heroes, not about Islam at all. Then, as soon as they got into war with Iraq, suddenly, they started printing editions of Shahnameh, pocket editions, big editions, ceremonial editions and so on. The White House hasn’t read the Shahnameh. If you read the Shahnameh, you realize that you cannot deter Iranians by killing any number of Arabs.

Deterrence starts with that. Deterrence starts with understanding the mind of the enemy. What will deter him? Because you don’t do deterrence. Deterrence happens in the mind of the enemy. Therefore, it’s conditioned by what the enemy thinks is dangerous and not dangerous. You could not deter a Japanese suicide pilot, because he was serving the emperor. He was achieving the maximum possible thing.

Imagine I could sink an aircraft carrier, bringing so much joy to the emperor, and I will become famous. No way you could deter this. You have to deter by starting the mind of the enemy.

Now, in the case of the Soviet Union as an empire that was built on strategy, Russia was and still is today the largest country in the world. Nobody gave it to them. They got it because they won the wars. They won the wars. They won the wars, because Russians understand strategy. They understand only two things, poor Russians, mathematics and strategy. The Israelis think that Jews are very smart and all that. When the Russian Jews arrived from the fall of the Soviet Union, which they really loved to bring about as people then recognized, because they rebelled openly in Red Square. Nobody else did. Of the 80 nationalities, only the Jews went to Red Square with the Jew flag, starting the whole process.

When these Israelis would convince themselves hard, when the Russian Jews arrived, and not all of them came from Downtown Moscow, they came from everywhere, from all remote areas, suddenly, the Israelis realized that they’d never been teaching mathematics in Israel. They had no idea what mathematics was. These refugees on arrival didn’t have anything. The first thing they insisted on was to set up after school math classes.

You have to understand that to deter the Soviet Union, what you had to do was to say to them, “Okay, remember World War II? We are going to destroy much more than the Germans destroyed. Much more.” The doctrine came out, a massive retaliation. That was a perfect doctrine for Russia to understand.

Now, it’s much harder to deter Iran today, because [during the Biden administration] when the Iranians look at Washington, they saw Robert Malley, who was their agent, basically. I don’t say he was an agent in the sense of being a paid agent, but he was somebody who was highly sympathetic to Iran and hated Saudi Arabia and hated Israel. He’s a second-generation Zionist hater. His parents hate Zionism so much that they work for the FLN in Paris.

They saw Malley, who is the ally. They saw Sullivan, who was a very nice young man at the time. He was the one who negotiated in Vienna and made all the concessions under the table to the Iranians. Along with Burns, who was the head of CIA, but also a very important advisor, really.