EMERGENCY POD: Tariffs on Trial

Our first-ever Supreme Court-driven emergency pod! Oren Cass, the founder and chief economist of American Compass, and Peter Harrell, former Biden White House official, host of the Security Economics podcast and, as of a month ago, a Georgetown Law scholar, have joined to discuss:

Why Trump’s most arbitrary tariff impositions might be the most easily defensible in the Supreme Court case,

Why this Supreme Court case probably has no real bearing on negotiations with China,

The USMCA as a template for negotiating with Asia,

What tariff negotiations can tell us about Trump’s philosophy on decoupling from China,

How the U.S. can compel allies to take defense seriously.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app or watch on YouTube:

Litigation Day

Jordan Schneider: Oren, why don’t you kick us off?

Oren Cass: I love the case as a legal matter. While partisans on both sides will tell you this is a clean-cut decision, I think there are actually many very close legal questions, which is fascinating.

The reality is that we are almost surely going to get a decision that attempts to put down some long-term markers for how the court thinks about these questions, while on the specifics of the tariffs, essentially trying to stall. The court will probably give a bunch of new guidelines and principles and then remand the case back to a lower court to figure out how to implement them. It’s a little bit like what you saw them do with the presidential immunity question.

The result will be that everyone will have a better sense of how the court would initially decide this, but there will be more time before anything is actually resolved. In the interim, the administration will have to figure out what it wants to move on through other authorities, what it wants to keep fighting on, and what, if anything, it wants to legislate. Anyone who’s looking for a clear-cut and decisive victory or devastating loss will almost surely be disappointed.

Peter Harrell: I might disagree a bit with you, Oren, on that. I heard a majority of the court was skeptical that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) authorizes at least all of the tariffs that Trump has imposed under IEEPA. While we could see a decision that holds that some IEEPA tariffs are authorized and then kicks the case to lower courts to sort out the exact parameters, I think we are more likely than not to find that at least the “universal and reciprocal” tariffs (the 20% on Vietnam, 15% on the European Union, 19% on Thailand, etc.) are not authorized under IEEPA.

I could be wrong, but I heard a fair amount of skepticism from the Chief Justice, Justice Barrett, and even Justice Gorsuch on the extent of the IEEPA’s authorization.

To your broader point, even if the court does strike down a decent chunk of the IEEPA tariffs, the administration has fallback options, as Ambassador Greer and other administration officials have said. I think we will see the administration work through other authorities to put some of the tariffs back together.

I agree with you that the decision may be narrow in some sense, as it will be about what this 1977 emergency power statute says. However, I also think we will get some broader discourse in the opinion about how the Supreme Court thinks about its major questions doctrine and about executive power versus congressional power generally. I think this is a decision that students and lawyers will be reading for some time to come because it will have broader ramifications beyond just a particular case on tariffs.

Jordan Schneider: The weird wrinkle of all this is that if the administration didn’t have “Liberation Day,” but just spent a few more months writing some Section 232 findings, or even had ChatGPT write the Section 232 findings, the standing for the Supreme Court to jump in and say, “You can’t do this,” would have been much smaller than the route the Trump administration ended up choosing. Am I wrong on that?

Peter Harrell: All of us who think about trade law are now unpacking these other statutes and thinking about what he could do under them and what their limits are. For your audience, Jordan, who may not be deep in the weeds here, the tariffs at issue in this case are the IEEPA tariffs — the universal and reciprocal tariffs, the so-called fentanyl tariffs on Mexico, China, and Canada, the tariffs on India over its oil import purchases, and the tariffs on Brazil over issues with former President Bolsonaro. It is not the product tariffs, so we are not talking about the steel and aluminum tariffs or the car tariffs here.

When I look at estimates from the Yale Budget Lab and others, roughly 70% of the tariffs Trump has imposed this term are at issue.

I think Trump has used this statute for two reasons. First, as you suggested, Jordan, the alternatives all require process. Trump has done a bunch of Section 232 investigations on cars, steel, and aluminum. But, as we are seeing with the fact that he has had a Section 232 on semiconductors for six or eight months that he has not yet completed, these things take time. Trump is not known as somebody who has a lot of patience when it comes to trade policy, and he does not want his administration to wait months and months before putting tariffs in place. IEEPA has let him avoid the time and fact-finding element that other statutes require.

The other thing is that if you really unpack these other statutes, I think he will find some substantive constraints on them. Now, a lot of these statutes haven’t been litigated much, so we will see what substantive constraints emerge. For example, Section 301, which he used to impose tariffs on China during his first term (something I very strongly agreed he was correct to do), arguably has some substantive limits. The quantity of tariffs must be tied to an unfair trade practice by the foreign country. With China, it is very easy to justify even much higher tariffs based on unfair trade practices. But if you wanted to maintain, say, a 10% tariff on Australia, a country we have a trade surplus with, it is difficult to identify an unfair Australian trade practice that merits a 10% tariff. You might be able to find something, maybe related to how they regulate our big tech companies, but I do think he would find some substantive constraint on some economies.

As I think about it, if he loses and decides not to go back to Congress, I think he can recreate more than 50% of the tariffs. But I do not think it is 100%, even after he jumps through all the hoops that these other statutes require.

Trump announcing his tariffs on “Liberation Day” (April 2, 2025). Source.

Oren Cass: I agree with Peter. I think the universal global tariff is the piece that is the hardest to justify under either IEEPA or through a Section 301 or Section 232, and it is probably the piece where you are most likely to need legislation if you actually want it to be a permanent part of policy.

The irony is that the stuff people are most frustrated with Trump over — the stuff that seems most unsubstantiated, like, “We don’t like the ad that Canada ran, so here’s another 10% on Canada” — is in a lot of respects the stuff that is most defensible under IEEPA or under an executive authority where the premise is, “Look, we’re negotiating here. We are using tariffs quite explicitly as a tool of foreign policy to try to strengthen our hand in negotiations.” You could not possibly do that through legislation. You couldn’t go back to Congress in the middle of a negotiation and say, “Hey, now we want you to do X instead of Y because that’s what we threatened at the table yesterday.”

This is where I agree very much with Peter that at the end of the day, within everything that has happened under IEEPA, there are actually just a lot of different rationales and different legal implications. That’s where maybe we disagree a little bit — I think it is very likely that the court’s take is going to be to try to draw out those strands and then send it back for somebody else to figure out. I think it is very unlikely that the Supreme Court would simultaneously try to distinguish all of these different things de novo. That would also at some point become new findings of fact that you would need to then implement. That is where I think you will see the Trump administration ultimately get some breathing room. But then, in terms of what U.S. Trade policy is going to be for the next decade, we probably and hopefully need to start laying down something more permanent than an emergency power before we look forward.

Jordan Schneider: Peter, I’m curious to what extent the specter of the fentanyl tariffs being taken off potentially impacted the negotiations between Xi and Trump at APEC.

Peter Harrell: I actually don’t think that the specter of Trump losing tariffs in court has that much of a meaningful impact on the China negotiations. I’m not even sure it has that much of a meaningful impact on any of the negotiations, but China in particular. Because there is an existing Section 301 on China and because there are other Section 301 investigations underway (an existing one from Trump’s first term and one on Chinese shipbuilding), China is the country he could most quickly and easily pivot to these other dials to re-impose the tariffs. I think it has almost no relevance to the China negotiations.

It has only limited relevance to some of the other negotiations. When I talk to European and Japanese officials, they are all watching this court case with great interest, but they also understand that Trump could recreate at least a portion of these tariffs under other authorities. They have a pragmatic view — “If Trump loses this, he can recreate some of it under other authorities, so why would we anger him by provocatively walking away from the trade deals we’ve just signed?” I do think that if he loses in court, you might see the European Union move more slowly to implement some of its commitments under the trade deal while Trump figures out his next steps, but I don’t think you would see a lot of walking away.

One final point — I do think we would have seen a pretty different case yesterday if a much narrower set of tariffs had been on the table. If the tariffs had just been on India for its purchases of Russian oil — something we’ve long used IEEPA sanctions to deal with — I think you would have seen a very different tone yesterday. But the Justices are looking at a whole panoply of tariffs, and that framed the skepticism we heard yesterday in many ways that we wouldn’t have heard if Trump had, in fact, used this more judiciously.

The question I wanted to ask Oren, sort of looking forward, is about Congress. The small-c constitutionalist in me thinks if we are going to have a reform in U.S. trade policy as big as the one we are currently undertaking, that is fundamentally a congressional prerogative. For this sort of thing, you should go to Congress and get legislative change. I’m also a realist, having dealt with Congress for many years, and I know all the challenges of getting Congress to do anything. I am interested in hearing your thoughts: Do you think there would be a path now in Congress, or over the next year and a half, to getting Congress on board with major changes in U.S. trade policy, or do you think, practically speaking, we are just not there?

Oren Cass: I think there is definitely a path forward. I divide the tariff policy question into three camps — the global tariff question, the reciprocal tariffs and negotiations with allies, and then China.

All of the reciprocal stuff going on, trying to strike new deals — do you ultimately get a USMCA that needs to go to Congress? Maybe. I don’t know what it would look like to legislate that piece of it. That’s why I’m most sympathetic to figuring out how the president has the authority to conduct what feels more like foreign relations to me.

When it comes to the global tariff, when it comes to China, I think there’s a path to move in Congress, and I think it is what we need. If you’re going to have a stable new expectation domestically and globally of what U.S. trade policy is, there is some — not a lot — bipartisan support for some sort of global tariff. If you didn’t have the incredible polarization of Trump on top of things, you could certainly see a world where Democrats would be at least as enthusiastic as Republicans about doing something here.

When it comes to China, I think there is definitely support. The main move would be to repeal Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR). That is where you have very substantive and promising legislation with many co-sponsors. If you made a political push on that, it is hard to envision who exactly these days would be fighting to maintain PNTR with China.

I think those are the two places the administration should focus, and there is some potential that they could or would. Ultimately, it comes down to — can anything move through Congress? You have to be sympathetic to some extent to an administration saying, “Well, if we can’t even fund the government, it is hard to envision getting a big bipartisan win for the president on elements of the trade stuff.”

Fortress North America

Jordan Schneider: Oren, we talked earlier about how Australia should be the most excited about this ruling, not really China. You have this vision of a grand strategy of reciprocity. I’m curious — to what extent could a Supreme Court ruling back the president into the type of global trade relations that you’d actually be more excited about?

Oren Cass: I don’t know that a Supreme Court ruling could have that direct effect. I think in a world where you get the kind of ruling I think is most likely — one that signals to the administration, “You have a little more time here, but you do need a different plan” — that is probably the best prospect to then see a focus on moving in Congress, which I think would be useful.

But in terms of what the overall strategy is, that is where we’re still waiting and really need the clarity from the administration, mostly from Trump himself, on where this is all going. Is the goal to get a big deal with China, or is there a recognition that there isn’t really a deal to be had?

We are right at the point now where what a renegotiated USMCA is going to look like is very much in focus. I see that as the linchpin of whatever we are building. USMCA, as it is structured and agreed to, will be the template. The administration needs to articulate very clearly what we actually want from USMCA if we are going to not just demolish the old system (which I think needed demolishing) but actually be building something better.

Peter Harrell: I very much agree with you, Oren, that USMCA is the linchpin. We are right now getting comments due to USTR on what stakeholders want out of USMCA, and I think this is going to be the central issue. If the Trump administration is going to succeed over the next three years in building a new order, as opposed to just putting the final nails in the coffin of the old order, this is absolutely the linchpin.

There are a couple of reasons for that, not least that these are the trading relationships where we have by far the most leverage. We import 80% of Mexico’s exports. These are wildly asymmetric trading relationships in terms of our leverage. Putting aside all the strategic interests we have in North America, this is the opportunity we have from a tactical negotiating perspective to really negotiate something very new and very interesting. I certainly hope the Trump administration takes advantage of it.

I was actually quite interested two weeks ago when we got the first actual deal text of what some of USTR might be thinking from the Cambodia and Malaysia trade deals. There are actually a lot of interesting provisions in there to unpack. I give the administration quite a bit of credit for some of the details they put in those deals. But we can make those much more real and deeper in the USMCA context. That is where we can really start the process of building a new order.

Jordan Schneider: You want to highlight some of them, Peter?

Peter Harrell: Yes, we can start with the China-focused provisions of the Cambodia and Malaysia deals. A lot of this will, of course, need to be implemented, but let’s start with the promising parts.

You saw both Cambodia and Malaysia agree that if the U.S. raises a tariff or non-tariff barrier — for example, a restriction on Chinese telecommunications equipment — we can notify them, and they have committed to taking comparable action under their domestic law. If that is followed through, that is a huge win for the United States.

It was also interesting in Malaysia. One of the things the Trump administration and others worry about is what Chinese companies are doing in third countries — are they setting up factories in Malaysia and then dumping products into the U.S. market? Malaysia and Cambodia committed that if we raise concerns with them about the actions of Chinese companies in their markets that impact our market, those countries would take action. Both countries also committed to setting up an investment screening law. These are commitments we have to see implemented, but there were some very promising signs coming out of those deals.

Oren Cass: I want to jump in on the USMCA point quickly. I agree exactly with what Peter was saying about these other deals — both that they are very interesting, and that how robustly you can implement those sorts of commitments with Cambodia remains to be seen.

Those kinds of commitments in a USMCA, however, become a total sea change in the way trade policy is conducted globally. In my mind, what is so important about USMCA is, firstly — it’s where we have the most leverage. We should treat Mexico and Canada well, respectfully, and as equal partners, but they do not really have other options, creating a unique opportunity for the U.S. to define what it wants.

Then, because of the history going all the way back to NAFTA, there is a capacity to robustly implement and enforce commitments in a way that will become a proof of concept for this stuff actually happening beyond just being on paper.

Finally, if we successfully structure USMCA in a way we want, it then becomes a fallback for us relative to all other negotiations — what some folks in Washington are now calling Fortress North America.

If the U.S. were truly going it alone, you could have real concerns. But if the U.S. is going forward with USMCA, with the size of that full market, the security commitments, and the diversification that Mexico and Canada bring, the U.S. can credibly say, even to Japan or the EU, “Here are the USMCA-like terms. We would love to have you in our trading bloc. If you’re not up for that — if you are insisting on remaining open to China, if you’re not willing to commit to bringing greater balance to trade — then good luck to you, because we actually have something better than continuing to work with you in the way you have been working.” If we can get this right, the U.S. then has the foundation to build from an improvement on what the prior system has been and a credible fallback for any other negotiations taking place.

Jordan Schneider: Peter, how credible is “Fortress North America” — the trade side of the Monroe Doctrine?

Peter Harrell: I think this could be pretty credible, and I do think it creates, as Oren says, this potential gravitational pull that then gives us more leverage in our trade negotiations elsewhere. I think this is pretty credible. It will require complicated, tough negotiations, and it will require a disciplined and sustained focus on this issue over six or nine months, which has not always been the President’s strong suit. I know that his trade team — Ambassador Greer and Secretary Lutnick — see this. I am optimistic that we are going to see a very interesting deal come out of this. We are going to see a bit of an attractive fortress that other folks will start wanting to join, starting in the back end of next year.

Oren, I really enjoyed your recent piece in Foreign Affairs where you argue for a grand strategy of reciprocity. The way I read your piece, you are arguing there should be three core elements to a trading bloc — commitments to take care of our own security, commitments to balanced trade, and commitments to getting China out of our operating system. I wonder if you could unpack how you are thinking about this and how feasible you think it is as a strategy.

Oren Cass: I think it is certainly feasible, given the steps we are already taking in this direction. We are seeing in these negotiations with countries that should be U.S. Allies on all three fronts an acknowledgment that this makes sense.

It is a starting point for other countries to acknowledge that the U.S. has a legitimate concern about balanced trade. Frankly, these other countries do as well. The funny thing about Germany or Japan, which have been the flip side of a lot of these imbalances once you set China aside, is that their economies are suffering from it as well. It has been a problem for Germany and Japan to be suppressing domestic consumption and relying so much on exporting. There is a potentially mutual benefit in moving to a more balanced model.

Likewise, when you think about China, everybody enjoys the short-term sugar high of the cheap stuff from China, but everybody also recognizes the long-term danger. One of the really interesting effects of the way the U.S. has started to confront China is that it heightens that pressure on everybody else. People ask why the U.S. didn’t just get together with allies and agree to confront China together. The answer is because no one else would have been willing to do that. The Biden administration tried that for four years, and asking nicely just doesn’t get you anywhere.

Peter Harrell: Yes, we certainly talked about it.

Oren Cass: It is not a novel concept that Western democracies should confront China, and obviously, that would have been great. The reality is that for many of the same reasons the U.S. political system refused to address it for so long, other market democracies have had a real problem doing anything about it, and cajoling just did not get us where we needed to go.

Credit to Trump: when you actually say, “Fine, watch this,” not only do you prove you can do it, and obviously, this is not free — there are costs — but it has not destroyed the U.S. economy to have very high tariffs on China and to be starting to drive a real decoupling. All those surpluses then start to backwash instead into the EU, and the EU now faces a much sharper choice than they were before. At least they are really put to the choice now in a way that they were trying to avoid.

You see these model agreements, even with Cambodia or Malaysia. You have certainly seen Mexico take the need to confront China more directly very seriously. Canada is busy on its quasi-liberal fainting couch about all of this, but at some point, they will get serious as well. That side of it is painful and costly, but it is in the mutual interest of all of these countries.

The third piece, security, is the same story. Cajoling and saying, “Hey, guys, wouldn’t it be great if you actually took your own security seriously?” is not a novel concept. We tried that for a very long time, and it simply did not work. What you are now seeing within the Trump framework is much more serious commitments in Europe and Japan to actually taking responsibility for security in their regions. It is a realization that that is good for them. It is expensive, but it would be much better if Japan, Korea, and Australia could credibly deter China over Taiwan. Plus, if Taiwan actually spent on its own defense, instead of everyone looking over their shoulder, wondering if they’ve done enough homework. The same applies to the EU — if they want to deter Russia and be secure in Europe, the way to do that would be to deter Russia and be secure in Europe. By putting them to these choices, it is understandable why they are sulking and frustrated, but if you step back and look at it from a neutral perspective, it all actually makes a lot of sense.

Jordan Schneider: I did a show last night with Jake Sullivan, and “How hard could you have pushed the Allies?” was, not surprisingly, a theme. The one hypothetical he did deeply entertain was the one where you just do the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) on the semiconductor export equipment and say, “Sorry, Korea, sorry, Japan, sorry, Netherlands, we’re the hegemon. Deal with it.” I’m curious about your reflections on this. My hypothesis was that Biden went into office with the central thesis being, “We need to repair our alliances.” If that is your core principle, then doing the thing that Oren highlighted — the United States saying, “Do this and stop that,” but rarely saying “or else” — your “or else” credibility just isn’t really there.

Peter Harrell: President Biden was very alliance-focused. Going back to his days in the Senate and as Vice President, he truly believes, going back to his memories of the Cold War, in cooperative games rather than confrontational games. A clear directive from the President was that we should focus on working things out and use inducement-oriented cooperation on China, as opposed to a threat-heavy approach with our allies.

I do think one of the lessons of the Trump era that we should be taking seriously as a country is that sometimes you need to be prepared to deliver a firmer “or else” message. That is a really important takeaway.

I actually think there is another, deeper critique of the Biden administration’s trade policy — although it had a clearly thought-through geopolitical logic (“Let’s get our allies and partners on board”), I actually think the Biden administration did not have a clearly thought-through economic logic of what it wanted out of trade policy. It was too internally torn — are we now in an era where, from our own economic self-interest, we actually want higher tariffs because we are trying to onshore manufacturing to the United States? Or are we still in some version of a neoliberal world order, at least among allies and partners, where there are very low barriers?

What you saw was an effort at a trade policy purely through the lens of geopolitics and not through the lens of economics. I posit that that was never going to work. Trade policy has to be about your economic vision — what do you want economically as a country out of this, not just geopolitically. That was the more foundational challenge, though I agree that when it comes to China, there is a clear lesson — we should have been prepared to be a little bit more stick-heavy.

Chip Bargaining + Trump’s China Philosophy

Oren Cass: Peter, I totally agree with your characterization of the Biden administration on the economic side. It seems to me less that they were unclear than that it was a house divided against itself. Ambassador Tai had a very clear economic perspective, but Secretary Yellen probably had a very clear opposite economic perspective, and I’m not sure that was ever resolved.

The China question is really interesting, though, because I look at Jake Sullivan’s “small yard, high fence” formulation, the first half of which is “small yard.” It seems to me that even toward China, the view was that the relationship was going to be viewed solely through a geopolitical lens, and there was this very small set of national security concerns to be narrowed as far as possible to ensure that a hypothetical broader, constructive relationship could still flourish. I’m curious if you think that’s fair to say that’s where the administration was or how you think “small yard, high fence” translates as a China policy.

Peter Harrell: I have two responses to that. First, Oren, I agree. When I say that the Biden administration did not have a coherent economic theory of the case on what it wanted out of trade policy, I very much agree that that was probably the result of many diverse views in the administration that were never reconciled. It was a problem of getting to coherence among divergent views.

On the question about China, it is interesting because I think, on one hand, many of the senior officials in the Biden administration, including the President himself, bought into this conceptual frame of a small yard of restrictions with a high fence, where most trade and most relations would be allowed to continue. I do think the administration was both internally divided and never got to a coherent perspective on how wide that yard is.

I remember once I was in Europe, and a friend showed me a meme going around about Jake Sullivan’s speech. It was a photo of a European chateau surrounded by acres and acres of lawn, with meme language saying, “This is Jake Sullivan’s yard.” There were certainly views about how wide the yard was.

Jake, to his credit, actually did have a view that it should be narrow. I think other people thought it should be wider. This is one of the fundamental questions we as a country need to coherently resolve — do we think we should have a 20% decoupling with China? Should we have a 50% decoupling? Or do we have an 80% or 90% decoupling? We need to start with what we think the end state should be and then build from that.

I personally am in favor of a fairly broad decoupling. I don’t worry too much about furniture, shoes, and garments from a national security perspective, but I do think we should have a pretty broad decoupling from China because I think it is in our strategic interest to do so. I also think, over time, it might actually provide some strategic stability to the U.S.-China relationship to be more decoupled, because we wouldn’t have these ongoing blow-ups and concerns about rare earths and things like that. We could have a less economically dependent relationship where we could then talk about strategic issues and maintaining geopolitical stability. That is not the view in my party (Democratic) or certainly not in the Biden administration. I think there was not a view that we should be 60% decoupled — I think it was sincerely something much narrower.

Oren Cass: I appreciate you making that point about this actually being a potentially more stable relationship because I think that’s super important. The thing that drives me most nuts in these conversations is this finite, descriptive term — I won’t use “midwit,” but it’s appropriate — for the idea that, “Well, countries that trade with each other don’t go to war, and if we disrupt our trade relationship, doesn’t that ensure World War III?”

I honestly don’t know where this idea came from. We had two world wars break out among countries that were literally bordering each other and closely economically intertwined. Then we had a 50-year Cold War where we agreed to have two systems that were mostly separate, and that was a far more stable arrangement that allowed for much less hot conflict. I don’t understand why we think that trying to manage the integration of these two completely different economic and political systems, two countries that are adversaries, is somehow a more stable world than one where we actually do decouple and concede each other spheres of influence. That strikes me as a much more stable arrangement.

All that being said, you see in the Trump administration almost an inversion of what you were describing for the Biden administration, Peter. In this case, you have much more consensus on the economic picture, but much less clarity on the geopolitical side. A lot of that comes from President Trump himself, who has been too consistent on China. You go back 30 or 40 years ago, his attitude was, “We’re getting screwed, we need a better deal.” When he ran for president in 2015, “China’s screwing us, we need a better deal,” was the almost out-of-the-Overton-window hawkish position. Everyone got locked in their heads that Trump is the China hawk. They spent his first term trying to get a deal, and he got the Phase One deal, which did not resolve a lot of the fundamental issues.

Since 2015, broader economic and political views in Washington have shifted so far that “We just need to get a better deal with China” is now the sort of dovish position, almost outside the window to the other side. As far as I can tell, that’s still exactly where he is. Trump still thinks we are getting screwed by China and need to get a better deal. You see him very focused on this idea of how to get a deal with China, which makes him the ultimate China dove within the Trump administration.

There is a very clear focus economically on this idea of reindustrialization, reshoring, and balanced trade that is consistently held and articulated by Trump, by Vance, by Bessent, by Lutnick, by Greer. That is terrific. On the question of what the actual goal or end-state status quo with China should be, I don’t think we are hearing as much clarity as we need to see.

Peter Harrell: That’s a really interesting point. It does look to me like former President Biden and a bunch of his senior staff saw China as a geopolitical threat — lots of focus on Taiwan, lots of focus on the military strategic issues. Economics were important but were probably less important overall than the strategic issues.

I look at Trump, and to your point, it is very interesting — it is not at all clear to me he sees China as a strategic threat or a military enemy. He clearly sees them as a trading threat and as a country that has been ripping us off for years. But he also thinks everyone else has been ripping us off for years. It looks like he may think, “If I can resolve the trade issues with China, I’m not as worried about these strategic issues.”

Oren Cass: The two best proof points of this are,

He is still very interested in Foreign Direct Investment from China. You have seen him out on the campaign stump saying, “Maybe we should get BYD to come build factories in the United States.” If this is just about the economics and there is no geopolitical or strategic concern, then yes, we like that Toyota is here, so we should get BYD here.

The other place you see this is on the advanced AI chips. There are people trying to do this “galaxy brain” argument where, “If we can get China hooked on the Nvidia chips, this will ensure that China adopts an American AI stack.” This sounds like things people were saying about moving production to China in 1999. The actual motivation seems to be, “The goal was to sell more stuff to China. One of the things we are really good at making is advanced AI chips, so we should sell them to China.”

That is wrong, but I have more respect for it because if you only care about the economic side and you do not think about the geopolitical side at all, then it kind of makes sense. On both these issues, you see very clear, ongoing, robust debate within the Trump administration. This debate is not from a bunch of people who are unsure, but from different people with very concrete perspectives. In a sense, Trump himself is the outlier on some of this at this point.

Jordan Schneider: The weird thing is that in the Biden administration, when there were disagreements, you just kind of didn’t really have any action or decisions. In Trump world, when there are disagreements, we just change our minds three times.

Oren Cass: You get them all at the same time. Exactly.

Peter Harrell: Yes, indeed. I’m curious about the chips issue, Oren, because you have obviously been writing quite a bit about this lately. From where I sit, having seen that Trump got through his meeting with Xi without seeming to put the high-end Nvidia chips on the table, I viewed that as a very important development for U.S. national security. Credit to the team around Trump and to Trump for seeing that we should not be putting our highest-end capabilities in the hands of the Chinese, given the intense competition and where we are in the state of the race. I am curious if you think this is going to stick. There is a piece of me that’s a little worried: It was great in Asia that you didn’t do that, but are we going to see Jensen in the Oval Office in another three weeks and some revisiting? How do you think we can make sure this sticks going forward?

Oren Cass: You described the dynamic exactly right, Peter, which is that there’s a live-to-fight-another-day element here. I don’t think this reflects a resolved, finalized, “not selling chips to China” policy. But look, at the battle-by-battle level, there was a meeting where that could have gone either way, and it went the right way, and that’s great. That’s certainly better than the alternative.

More broadly, this is ultimately best understood as one dimension of the larger China discussion. That’s part of the reason I’ve become so interested in it — we’ve been doing a lot of work on it at American Compass — it is very much the tip of the spear litmus test for how you think about China because it is so clear and discreet.

To your point, yes, there’s this much broader discussion — what exactly does decoupling mean? What share of trade are we talking about? How much is it trade versus investment? What does it mean for allies? All of that is super important, but it doesn’t lend itself as nicely to a clear pro/con debate in a lot of cases. It’s really important to have clear, distinct questions that you can anchor on, which make people put their underlying assumptions on the table and say, “Look, if you believe X, you come out this way on the question. If you believe Y, you come out this other way.” That’s where something like, “Does it make sense to sell advanced chips to China?” or “Does it make sense to have BYD investing in the U.S.?” are such useful places to focus the policy discussion.

On the chip debate, I think it’s very much moving in the right direction. It’s notably a place where you’re seeing Congress be somewhat active even in the face of the Trump administration. The GAIN AI Act, which is frankly a very narrow policy — all it says is you can’t sell advanced chips to China where there is literally an American company saying, “No, please let us buy the chip instead” — even that the Trump administration initially signaled its opposition to. That did not stop Republican senators, Senator Banks, and Senator Cotton, the co-sponsors, from saying, “Sorry, we think this is important.” It’s in the Senate version of the NDAA.

That is one very important political dimension to it. Another is looking at where the tech sector is aligning around this stuff. We all know Jensen at this point, and it is genuinely bizarre to me how far out he and Nvidia have gone in ways that have just ruined for a generation their credibility as at all interested in either good-faith political engagement or the American national interest. If I were a long-term shareholder, I would be very upset that that’s the way that they’ve gone.

Jensen is trying to talk his book on selling into China even as he increasingly goes into arguments that, to try to make his case, he now has to be out there saying he actually doesn’t even think it matters who wins on AI, or he thinks China’s going to win on AI, or he thinks China wants to be a market country where American companies succeed. The arguments just get increasingly ludicrous in a way that makes it harder and harder for the administration to say they’re siding there. You’re seeing the rest of the tech sector get pretty fed up with it too. It was really notable — you had Palantir’s chief technology officer write an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal essentially calling Jensen Huang a useful idiot.

Jordan Schneider: In the Wall Street Journal, and then the next week signing a deal with them.

Oren Cass: Right, so this is then another really good example. Palantir signs a deal with Nvidia, and the way they celebrate it is to say, “We’re so proud to be working with Nvidia because Nvidia’s technology is so key to U.S. leadership in the geopolitical competition with China and re-industrialization.” It’s such an incredible passive-aggressive move.

Obviously, everybody is scared of Nvidia because they want Nvidia chips. You even had Microsoft come out publicly and say they supported the GAIN AI Act. I think everything has been moving in a good direction on this. We are winning in the present tense, the fight. But as Peter noted, and I would acknowledge, you are always one Oval Office meeting and tweet away from heading the other direction. So frankly, this is another argument for Congress to be involved, as we were talking about back in the broader trade context. The question of our export control policy toward China ultimately should be legislated, permanent, and stable. It is an issue where there is bipartisan agreement, where this is Congress’s role, and I think they should make a law.

Jordan Schneider: Two things. First, listeners of the show will have heard many guests who are in favor of strong export controls to China. What is remarkable to me is how hard it has been to find someone to talk the other side of this who isn’t directly financially compensated by firms that would make money if export controls were lifted. It’s not for lack of trying for me to get another side of the debate, but if you’re out there and you’re sharp on this stuff and you want to make the case, send me an email.

Peter Harrell: Jensen should come on the podcast.

Oren Cass: Jensen is eager to say foolish things on every podcast. I’m surprised he hasn’t called.

Jordan Schneider: I’ve sent the email.

On the second point, say you actually have legislation — does that change the sort of escalation/dominance dynamics around this stuff? If China is trying to undo something, then they can threaten X, and then Trump will have to tell his Commerce Secretary, “Don’t do Y.” But if it comes out of a bill, then it’s less easy to negotiate about. Then, trying to threaten the Senate Commerce Committee gets them even more angry and they say, “Go screw yourself.” I’m curious how you think this escalation stuff would play out if it was really Congress that took the front role here.

Oren Cass: Peter, I’m curious what you think about those dynamics generally these days.

Peter Harrell: Let me offer a couple of thoughts, first on the export controls front because we’re talking GAIN AI, and then maybe coming back to the trade front.

The way I see it, for national security reasons, we should not be in the business of offering our most advanced chips to China. I don’t think this is something we should be negotiating over as part of our trade deals. There are plenty of other things we can negotiate with China. The idea that Congress would take this particular issue off the negotiating table, I see that as being in the U.S. interest rather than against us. From a negotiating perspective, it cuts both ways. The administration can’t offer it, but again, I don’t think they should be in the business of offering it. The flip side is they can just tell the Chinese, “I wish we could talk about this issue, but I can’t. We’re going to have to work something else out.” It changes that negotiating dynamic, but it doesn’t necessarily make it an unfavorable negotiating dynamic.

On the trade front, and this was a little bit lost in the debate yesterday back to the Supreme Court case, I actually think from a negotiating escalation/dominance perspective, there is more flexibility in the other trade statutes than they get credit for. I look at Trump’s first-term trade actions on China, and he used Section 301 pretty effectively to counter-escalate when China escalated on the U.S. That use of Section 301 to counter-escalate was upheld through the intermediate appellate courts when that got litigated. So I actually think that these other tools, once an administration does its homework — certainly for more competitive and adversarial countries like China — to build the regulatory basis for these tariffs, I think they would still find these tools to be reasonably effective.

From a negotiating leverage perspective, it is certainly true that Trump couldn’t use a Section 301 to threaten 10% tariffs because he is angry about a TV ad. But, on the other hand, he shouldn’t be doing that anyway.

Oren Cass: The point about it being good to take things off the table when we don’t want them on the table is exactly right.

The one other thing I would just add about the escalation/dominance discourse is that there’s almost a “tell” in the phrase escalation dominance. It sounds super exciting and cool, and it’s what all the people who in the past would have been planning various wars are now really excited to game out. It’s not clear to me that either side here wants to do any of that. It’s a little bit like mutually assured destruction, where I think both sides accept that they can cause massive pain to the other side. Who can shoot the most nuclear weapons at the other side is at some point not an especially important determinant.

Especially because in this case, I think we’re actually moving toward a situation, you can call it a détente, but a situation where both sides actually do kind of want to decouple. If you believe the U.S. wants to decouple, then you have that side. President Xi’s policy for a long time now has been to essentially develop total self-sufficiency, to not be dependent on anybody, certainly not the United States, for anything. While China certainly enjoys being able to sell lots of stuff to the U.S., one thing we’re seeing is that insofar as China’s commitment is simply to grow manufacturing and export, they have other places they can do that. Longer run, they are much like Germany and Japan — they are going to have to address their domestic imbalances and domestic consumption.

It seems to me that both sides kind of want to be at a 40% or 50% tariff with a slow but steady and not too disruptive decoupling. The rest thus far has proven to be, and I think rationally should be understood as, a lot of theater.

Jordan Schneider: I don’t think that’s the right way to characterize the Chinese view. There are many Xi speeches about how he wants to get the world more dependent on China and have leverage. Decoupling to the tune of 20% where we are now to 50%, or 80% over the next five to 10 years is going to be uneconomical and cost billions of dollars on either side. How much near-term GDP growth are we willing to put on the table in order to have China have less leverage? Is the way you’re characterizing this, Oren, that it’s okay for the U.S. to have these economic nukes pointed at us, because I don’t know how you follow a lot of the reciprocity stuff that you were pushing without facing down the enemy getting a vote here?

Oren Cass: No, I don’t think so at all. Maybe I was a little bit unclear in what I was saying. A huge part of the decoupling is that you, in effect, disarm those nukes over time. Where you’re seeing the U.S. focus first is on, alongside the sort of just general shifting of supply chains, things like semiconductors, things like rare earths that are the immediate concerns. The point in my mind is that I don’t think the U.S. necessarily wants to or expects to preserve some sort of weapon pointed at China in this respect.

EMERGENCY POD: Rare Earth Export Controls

China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) just announced a sweeping new package of REM export controls, claiming extraterritorial jurisdiction over the entire AI chip supply chain in the process.

I agree with your point that obviously China would love to have leverage over countries, would love to have the U.S. dependent on it for some of these things. At the end of the day, though, that sort of isn’t up to China. China got to do that as long as everybody else was being really stupid. But if the U.S. actually takes seriously the need to rebuild a rare earths capacity, China can’t stop it from doing that. What would that even look like? It would be China saying, “We’re going to fire the gun now essentially and try to stop you from developing a rare earth’s capacity by threatening that if you try, we’re going to cut off rare earths now.” Yes, they could cause a lot of pain doing that. But as we’ve already seen over the last six months, even loading the gun just leads to more rapid commitment to building up the alternative capacity. And in firing the gun, the U.S. has a lot of guns it can fire back.

If you actually game it out, I just don’t see an end state. From either the U.S. or the China policy planning perspective, I don’t see how you could be expecting to plan for a world where you’re maintaining that kind of leverage long term. If you accept you’re not going to have it, then the question is, what’s the path from here to there? Is it worth blowing up a bunch of stuff on both sides in the meantime, or would you rather minimize the cost to your own side? I think both sides are rationally trying to do it in a way that minimizes the cost to their own side.

Peter Harrell: Jordan, my view is much less informed about Xi’s thinking than yours is, and I’m very well aware of that. It does seem to me that while Xi probably does want to keep the world broadly hooked on certain Chinese choke points, he has to be clear-eyed that if the U.S. continues to stay organized the way we have been over the last couple of years, and particularly frankly, on rare earths this year as the Trump administration has gotten very serious about it, he is going to lose that leverage at least vis-à-vis the U.S. Maybe the Europeans won’t get organized. He might be able to keep that leverage over other partners. I hope not, but he might. It just strikes me as a solvable problem from our perspective, and he strikes me as not stupid, so he has to be able to see that coming.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting what’s solvable and what’s not solvable. Is the world going to recreate the solar manufacturing ecosystem on the scale that China has, or the EV manufacturing ecosystem on the scale that China has? Perhaps. But rare earth seems like a much more manageable thing. We’ll see.

Supreme Court Improv

Peter Harrell: I listened to two and a half hours of the Supreme Court argument. I think this is the first one I’ve heard in maybe 10 years, and I just have some anthropological observations I’d be curious about both of your thoughts on. First off, it was refreshing to hear political discourse that is sharp and grounded, and they’re talking about facts. Second, I have this new hobby of listening to podcasts where these Orthodox or Ultra-Orthodox rabbis give their interpretations about the week’s parsha, and every eighth word is in Yiddish or Hebrew. Also, when I listen to Chinese podcasts, I understand about 85% of it. That was kind of what I felt here, where they’re just jumping around between all these cases, and you can kind of get the gist, but there is this level of arcana that is pretty impenetrable.

It did feel odd that we’re referencing people from 250 years ago, like they really matter today. There are not many other venues in society where we’re going back. It is kind of rabbinical, right, where you care about Rashi or Rambam the same way you care about Jefferson or Madison and how they thought about tariffs in 1802, or what have you.

The last thing — those poor solicitors, man, this is really stressful. They just get interrupted all the time, and they’ve got to think quickly on their feet. There was one moment in there where some judge said, “This point doesn’t make sense anymore.” After four back and forths, the government lawyer said, “Yeah, I guess so. Okay, let’s just move on.” That must be a lot. It’s very much like theater, like improv. You’ve got to know your stuff incredibly well.

Peter Harrell: Hopefully, you want to watch some more, right? Is this your future entertainment here? Instead of podcasts, you can listen to Supreme Court oral arguments.

I have a couple of reactions to that, Jordan. First of all, I agree with you. It is refreshing to hear a lively debate where you have people who clearly have an open mind and are grappling with multiple sides of an issue. I actually think this is what we want our court system to be doing. It did not strike me as particularly partisan. That’s not to say you couldn’t see Justices’ views coming into the courtroom — of course, you could. But you saw Justices grappling in a serious way with the complicated issues in front of them.

I agree it’s got to be hard for the lawyers arguing these cases. They were all, I’m sure, mooted many, many times. I’m sure they did lots of rehearsals for this. This is not something you wing it going into, but you certainly do have to think on your feet.

History — that is kind of the way our law works. You’re trying to build off of precedent. You’re trying to think about what the precedents are. You’re trying to relate the precedents to the facts in front of you. On the thing that came up that is most historical in that case—and here I’ll go a little weedy—the challenge the government has in this case is that, as you heard the Solicitor General concede, there is no other part of American law where the phrase “regulate... importation” includes the power to tariff. There’s no other phrase in American law where “regulate” by itself includes the power to tariff. The government’s argument, and it’s certainly true, is that back in the 1790s to 1820s, everyone understood “importation” as including a power to tariff. They kind of have to rely on this early historical understanding of that phrase because of the absence of more contemporaneous precedents in support of their position.

Jordan Schneider: One more question for both of you guys. Do the arguments actually matter? There are hundreds of pages written on all of this. Is the quick quip you have in response, which was only going to be about 150 words anyway, actually going to persuade a judge one way or another?

Oren Cass: I agree that that oral argument seems majestic and open-minded and the kind of deliberation we want. If this case were being heard two years ago about a Biden administration use of IEEPA to try to force a global climate agreement, do you think those nine judges would have simply been asking exactly the reverse set of questions in preparation for voting exactly the opposite way, or do you think this is how the conversation would have gone?

Peter Harrell: You would have seen a different lens. I think you would have seen a shift in the window of the debate there for sure. I actually don’t think you would have seen a radical 180, though. I think you probably would have seen the Chief Justice, Justice Roberts, and Amy Coney Barrett being a little bit more skeptical, but they had some skepticism yesterday. I think you would have seen Kagan and Justice Jackson more sympathetic to the government. But I think you would have seen them worrying about some of the presidential concerns that we saw Justice Gorsuch asking about yesterday.

And how this might play out over time. I do think it would have been a shift, but I don’t think it would have been a 180.

To your question, Jordan, about whether the oral argument does matter — I think probably in many cases it doesn’t matter. As you say, there are literally thousands of pages with all the amicus briefings and everything else in front of the court. But I do think there may be a couple of moments that I could see mattering yesterday.

For example, the strongest intuitive argument that the government has going for it — not really legal, we can talk about the legal — the strongest intuitive argument that the government has going for it is that if IEEPA would let President Trump embargo the world (and IEEPA does form the basis of embargoes on Russia and embargoes on Iran), if IEEPA would let us embargo the world, why does it not allow a tariff as a lesser measure? If it would allow an embargo, why doesn’t it allow a tariff? You could see a couple of the Justices really trying to grapple with that sort of intuitively very appealing argument.

What you heard the Oregon lawyer say, which got a laugh in the courtroom, was, “Well, it’s not that the tariff is a donut hole — it’s that it’s a different kind of pastry.” I think that is the kind of thing that will matter. If the Justices are not going to read a tariff authority into IEEPA, they will have to be persuaded that the tariff is just different from these other kinds of powers that are in IEEPA. I don’t know where that will come down, but that debate strikes me as something that you could actually see the Justices grappling with. A couple of them seemed open on the question, so maybe it will matter.

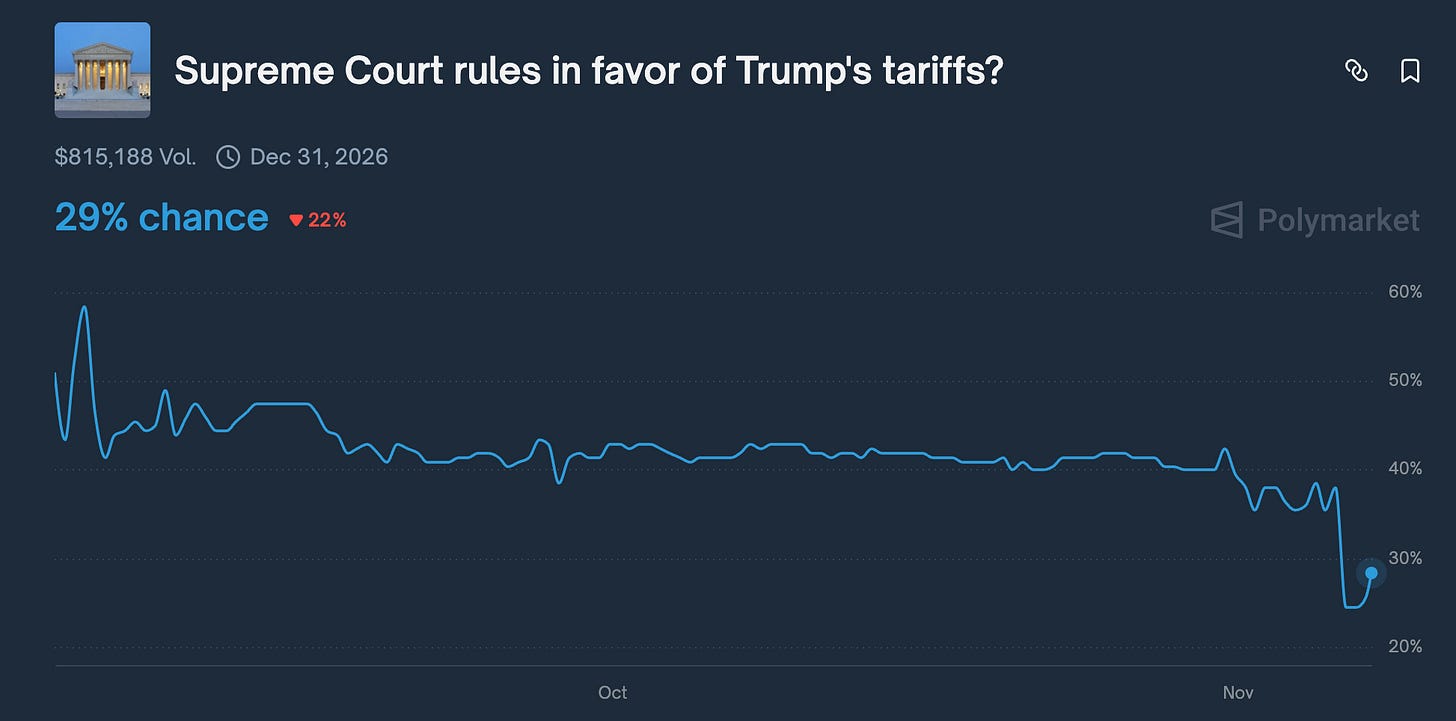

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, PolyMarket had it from 40% down to 20%.

Oren Cass: Wait, in which direction? What’s the contract for?

Jordan Schneider: There were two. I cannot believe PolyMarket hasn’t started sponsoring ChinaTalk yet I’m starting to get a little offended! The market was “Will the Supreme Court rule in favor of Trump’s tariffs?” It was at 40% when the debate started and is now sitting at 25%. Then there’s another market — “Will the court force Trump to refund the tariffs?” which started at about 8% and is now up to 16%.

If the goal of China and the U.S. is for each to have its sphere of influence, what constitutes China's sphere of influence if, for instance, Malaysia and Cambodia sign trade agreements which put them in the sphere of influence of the U.S.?

It's interesting that there seems to be a bipartisan consensus towards treating allies with hegemonic contempt, telling them a clear "or else". From a European (or Japanese) perspective it's hard not to conclude that the US is actually the worse threat than China, and maybe, in view of recent volatility in US policies, in the long term it might be better for those former US allies to get closer to China.