Evan Osnos on Trump and Tiananmen, Protests, and America's Place in the World

Yesterday I recorded a ChinaTalk podcast episode so good I spent all morning making a transcript for you. See below for my interview with New Yorker correspondent Evan Osnos and Tweets of the Week at the bottom.

Trump, Protests, and Tiananmen

Jordan: I find it unbelievable that it is even remotely possible to have a conversation comparing something happening in the US in 2020 with Tiananmen, but here we are. A few days ago, Bill Bishop highlighted an article winding its way around WeChat that takes Deng's famous public speech given one week after the events in Tiananmen and rewrites it to apply to Trump today. So the initial two lines were:

Although some comrades may not understand this for a while, we will eventually understand and support the decision of the Central Committee.

Perhaps this is a bad thing that will enable us to go ahead with the reform and opening policy at a steadier better and even faster pace to more speedily, correct our mistakes and better develop our strong points too.

Youtube video here…I forgot just how old and frail he was at the time.

This gets rewritten into:

They will eventually understand this and support the decision of the Republican party. Perhaps this thing will enable us to go further ahead with MAGA at a steady, or faster, and even better pace.

Evan: Well, you know, what's interesting about this Jordan. It's such an interesting moment, obviously, this almost bizarre cosmic overlap of the anniversary of June 4th with the very moment that we're having this national protest movement in the United States. For anybody who is an American China nerd, this is powerfully evocative.

My initial reaction was, hold on here. Let's be very cautious about making casual analogies because it can run the risk of dishonoring the scale of the tragedy at Tiananmen. We're talking about a huge loss of life in a matter of days in Beijing and elsewhere.

But there are really interesting parallels. And one of them being this idea of a leadership that is fortifying itself against its own people. That, for me, is the part that rises to the surface. Anytime you end up in a situation in which a leadership either sort of physically, geographically, or ultimately, those are all reflections of like spiritually and intellectually, they are literally barricading themselves against their own citizenry.

That's what's happening right now in Washington. And that's what happened in Beijing in 89. So even if we can bracket the comparison by saying, let's not get into the business of casually invoking Tiananmen all the time, because it undermines the seriousness of what happened in 1989, there are some really fascinating parallels there.

Jordan: And how about the executive military branch tensions, of course, famously in Tiananmen, there were leaders of the military as well as troops who were not at all down with the program which is a tension that we've certainly seen play out, with the Secretary of Defense coming out and saying 'we don't want to do this and have active military on the ground.'

Evan: And another comparison that's super interesting is that here in Washington, there are national guard units from around the country. So from Utah, for instance, or elsewhere, and what I found fascinating is that was a feature of the military strategy at Tiananmen was to get military units from far away from Beijing, so that they felt no personal connection to the people in the Capitol.

Oftentimes they regarded the people in the Capitol as these kinds of, you know, privileged, elite kids, spoiled brats, basically. It's not a stretch to see some similar kind of, over the mountains to Utah, from the palace here in Washington, bringing people in who don't feel connected to it, there is something eerie about that.

I was very struck by that as I looked at those images of the men in uniform at the Lincoln Memorial, which I think for a lot of us kind of galvanized crystallize this thing. That moment. and thinking to myself what's going on in that man's mind, as he thinks about the people here, before him, because there is that vast divide.

I don't want to quite say urban/rural, cause in some cases it's not really that, but it is definitely power center and province.

Jordan: It's really GOP/Democrat as much as anything else where you, where you saw a series of Republican governors, like offering up their tribute of a thousand national guard members. So not to just rag on Utah.

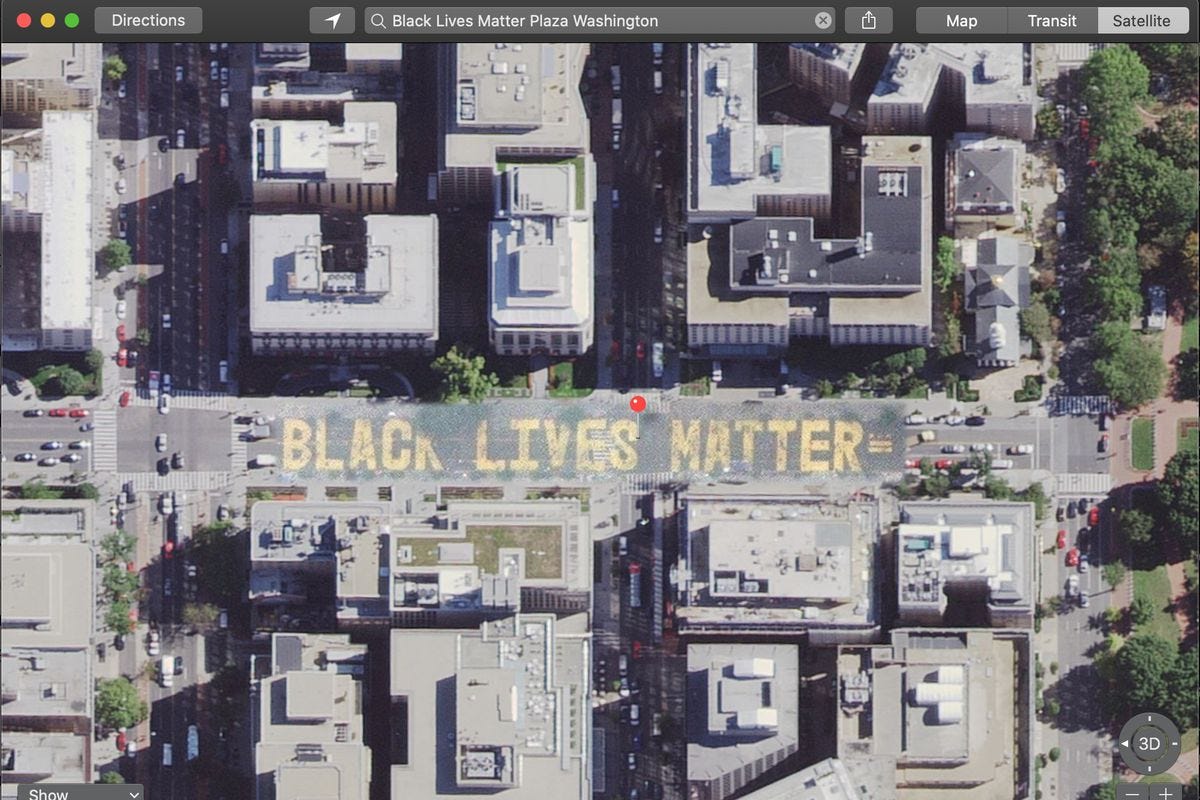

Evan: One of the moments that I was really struck by was having the mayor of Washington write Black lives matter in huge script down the middle of the asphalt so that Trump can see it from his helicopter when he flies away. I mean, that's an amazing moment of political expression, playing out.

Also, the fact that Arlington County, Virginia, when they withdrew their cops because they felt like they weren't being used responsibly in Washington. That's an extraordinary sort of exhibit of the nature of American governance that you have these different levels of the Federalist system at war with one another. And if you want to find a positive thing there, and there is something positive, it's that this is all happening and it's happening in public. And that we're sort of watching as different political leaders are using the power that they have, to check one another.

That's better than the alternative, which is having a central executive that is seen rolling over everything without the ability for these other layers to impede it.

Jordan: Joseph Torigian, a Western political scientist wrote a piece a few years ago doing a sort of retrospective on what we know now about the decision making that led up to the gentleman crackdown. And one of his hypotheses, which I think is fascinating to think about in the context of June in America 2020 is the idea that:

It’s possible that Deng understood that the protests could be defused without violence, but feared such a solution would have created an uncontrolled political space with unforeseen long-term implications. Deng was clearly afraid about protests becoming a regular feature of the political landscape and making the reform and opening up process more difficult.

Evan: I have a hard time drawing too close a comparison between Deng and Trump simply because Deng, for all his failures and some of them are profound and historic, he was of a different nature. He had, you know, done the reading to be blunt about it. I think Trump is basically operating from a fairly thin personal playbook, a combination of kind of adrenal impulses and, moments of political self-protection.

Deng made a catastrophic error at Tiananmen Square, but he was also probably operating with some more theory behind it, even if the theory was wrong.

Jordan: I think the sort of thinness of his thinking, really reflects back to this quote that he gave in 1990 to Playboy. Trump said that

When the students poured into Tiananmen Square, the Chinese government almost blew it. Then they were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength. Our country is right now perceived as weak … as being spit on by the rest of the world.

I think there is some gut-level where he just doesn't want to be shown up and sees folks marching in uniform as something that's a show of strength when obviously this is shows just how weak he is as a president.

Evan: What I found interesting about that quote is in some ways, Trump has been consistent over the years in his adulation of raw force.

You could take that quote that he gave to Playboy in 1990 and you could say, well, I wonder if Xi in a private moment would say something like that. He probably would, the difference, of course, is he is cannier about what he says in public.

It begins to help you then understand why does Trump look at people like Xi or leaders who have that power to use force and why does he admire them so much? On the most basic level, it's the application of force and the potential to use that. That is the chief seduction for Donald Trump when it comes to why he likes authoritarianism so much.

Jordan: It's interesting to think if Trump would rather prefer to be a leader in a different political system. But in order to rise up as a communist apparatchik, you need the headstart of having your father have revolutionary cred, but there's also a lot of games and like interpersonal dynamics that need to be played. If Trump was not elected president, like there is no way that he would win any bureaucratic power struggle.

Evan: Totally. All of us have heard from Chinese friends and counterparts this idea that the system in which you grew as a leader through all of these levels where they first started, they acquire almost a physical vocabulary of how to behave in certain settings. How you give deference to the person who is the leader above you and so on.

Jordan: So we've done Trump as Deng, but now let's do Trump as Mao. So you tweeted a quote Lin Biao from the great Frank Dikotter quadriliogy, where Frank writes:

There are delicious points of comparison between Trump and Mao. And it goes to anybody who imagines themselves as a figure of salvation. I have a soft spot for documentaries about cults. And anytime you watch something like that, you are reminded of the elements of kind of the catastrophes of overly charismatic leadership. I mean, charismatic in the technical sense, not as a normative compliment.

Protests and America’s Place in the World

Jordan: The protest movement has been something covered very aggressively within media in China, and has now been turned into a sort of political weapon. I’m curious about the protest movement and the government's response is and what impact it has on US-China relations and America's place in the world.

Evan: The protest movement is a sign of how the United States is struggling internally to prove that it's living up to the aspirations that it expects of itself and other countries.

To be blunt about it, it gets a lot harder to go and tell the Burmese government that you need to do better in protecting the rights of minorities and restricting the arbitrary use of force when we're having a movement in our own country that is demanding those very improvements.

I'm going through this process right now, thinking to myself. Okay. I've spent the last two decades writing from other countries about human rights problems in those countries.

I come to it as an American with some sense that yes, we are in this ongoing multi-century struggle of our own to try to live up to our core aspirations, whether it's, you know, equal opportunity, equal rights, a truly free press, and so on. Protections for minorities and for women and for vulnerable people.

And I am, I think, chastened and, made more humble by this period of recognizing just how much work has to be done in this country for us to even say that we're, an agent for those values around the world. That's the honest answer, you know?

Jordan: I think there's two sides to this coin. The obvious one that you spoke to with Burma, there's the one talking about sort of mainstream Chinese public opinion. You know, I've had a few conversations with, with friends, the stuff I read on social media, it's like “美国乱了,中国多好” ‘isn't it great that we don't have to put up with this shit.’ Mainstream Chinese see any sort of action on the streets as dangerous and scary, and that of course is amplified by every video you see on Douyin and state media broadcasts only showing people burning Targets and Nike stores.

But the point you alluded to is really important. I imagine this was also sort of the dynamic in 2003, with all the antiwar protests around Bush. It's important for the world to know that not everyone's on board with police brutality and what's going on in the White House. With Trump being such an outsized media personality and so easy to cover around the world, it's understandable. But I think just seeing all the solidarity movements that you've seen in all these capitals in Europe, it makes you hopeful that like enough people still believe that America can be something good.

Evan: There's two ways you can look at it. There's the superficial reaction to what's going on in the United States that you see sometimes from a triumphalist nationalist Chinese perspective that American democracy has always been a fiction and a lie and it is better to have suppression and quiet than to have, open, sometimes violent, protest.

And the other perspective is that silence is often a sign of the absence of political movement that's let's say bending the arc of justice. Oftentimes protest is painful and is also the sign that you're moving in the direction of something better. One of the things that we see in China is that the inability to have that protest, it's dangerous for the government to not really understand how, how, where, and what kind of dissatisfaction there is. And it's also a sign that it's not moving in the direction of greater fulfillment of those kinds of aspirations. [See Jill Lapore].

And then there's the other side of it, which is like, so yeah, American democracy as a brand. Is being harmed over the course of these few years, by the election of Donald Trump and the violence he has done to America's governance.

And then at the same time what we and the world are witnessing right now is that Americans actually believe enough in these concepts to go into the streets and put themselves at risk in order to try to push the country into a better place.

Jordan: So some say we're at an all-time low in US-China relations perhaps since Nixon. What's your take?

Evan: Here's an interesting point, why would we say Nixon in 72 versus Carter in 79? That's when relations were actually normalized.

The crucial ingredient was there in the 72 to 79 period, a fundamental belief in a shared notion of the direction. Even if they were wary of each other, they believe that they were heading towards a common destination, which was to try to bring these two huge powers into alignment with each other. And that's the thing that is missing today. At least they imagined that there was some way for these two to get along with each other.

How much of this would have happened if Trump hadn't come to power? The one that's actually much harder answer is how much is Xi is a product of this lower trust era with the United States, this higher tolerance for confrontation, all those kinds of questions. I'd be curious what you think.

Jordan: Li Keqiang just seems like much less of an asshole. He's like not a son of a bitch. And maybe the less 'son of a bitch' part of him is what gets put forward in the position he's in now, doing economic policy, liberalizing the food stalls, talking about poverty all the time. And clearly these are things that he cares about. But you know, when you're top dog, you also have to deal with the US, with the trade war, with Donald Trump. And it's not inconceivable that he would draw the same conclusions if he ran the CCP.

Ryan: The Xi we all began to see in 2013, 2014, when Donald Trump was still hosting the Apprentice, is very much the person that we see now. Xi arrived in office with a vision for what he wanted [to tighten up the country].

Given the fact that Xi is the leader, they'd take the maximalist authoritarian position and there's something similar with Trump there. You see people who might operate on a bandwidth spectrum of different behaviors, but because he is the boss and kind of validates these things, then they end up taking that maximalist position.

Can this Get Better With Xi Around?

Jordan: Is there any way this improves with Xi still in power?

Ryan: I can see it improving. I think that one thing that's worth keeping in our minds about it is that Xi is not delusional about China's ability to win a real war with the United States. Now, I know that's kind of going a little far down the runway in terms of your question, but like that is an outer bound on, on what, what I think, they're willing to do.

Jordan: That's a tricky framing of him because all it takes is one sort of miscalculation. Say Xi thinks all right, 美国乱了, let's play with Taiwan and see what happens. And then, all of a sudden, a lot of things get out of his control.

And regardless of the prior he has that like American carriers aren't as shitty as some of his admirals think they are, you still end up in a really scary situation because he has this other prior that Taiwan's defenses aren't all there cracked up to me or net-net it's a positive for my domestic political position or for like the glory of China.

Evan: You've kind of persuaded me. I have to say, you set out a hard task, which is, in the midst of a global pandemic with Trump as president and the US- China relationship at its worst point in history, is there any reason, is there any conceivable course for optimism?

Jordan:You know what also really bumped me out, and this is less serious than a war in Taiwan, but, as listeners know, I spent a fair amount of time following Chinese hip hop and, what I found really remarkable over the past few weeks is the extent to which the global K-pop fandom has really gotten behind Black Lives Matter, donating millions of dollars to bail funds and police reform.

Bt the hip hop artists in China who have made their livings off of black culture, and oftentimes say, "We respect our elders and like, if you don't listen to Big Pun then you're not real hip hop" [yes, I know Big Pun is Latino] the silence I've seen from them is just so depressing. You try to look at things like cultural connections and, the fact that so many Chinese love the NBA and whatnot as sort of hope for the future, but if even the folks whose livings are built off of black culture in America either that it's too dangerous for them to say ‘black lives matter’ on their domestic Weibos or it just doesn't resonate with them is just so disheartening.

Speaking of international cultural capital in this January piece you wrote about US-China relations, you had a bit about Hollywood and how they're beholden to the Chinese market. But it occurred to me that there's one studio that has zero China exposure, which is of course Netflix. I think they've probably gotten the message at this point that they're never going to enter the market. So, what would you pitch to the Netflix execs for a show about Chinese politics?

Evan: I've always thought that the best description of Washington politics having moved here is not House of Cards, its Veep. Veep captures all of the positive vanities and the small ways in which people make bad decisions all the time. And one of the things that we don't get when we talk about Chinese politics is, is some of that.

We sometimes talk about the Death of Stalin as such an interesting window into the nature of authoritarian governments and why people do the things they do. Death of Stalin is an appropriate reference for understanding Trump world these days, too, because all of that sort of the mythmaking and the creating of worlds around him and so on. I would love to see something funny about Chinese politics.

We don't see that very often.

Jordan: Any broader reflections to sum up the differences you've had just reporting on the US over the past six years versus your stint on the mainland?

Evan: I spent a long time living overseas and reporting on, on political culture in other places. I’ve lived in Egypt and reported a lot in Iraq and lived in China obviously. And in some ways, coming back to the United States has been a process of coming to understand and trying to answer the question for myself of how we became so alienated from the values that we try to project around the world.

I actually feel almost like a personal responsibility to go back and begin to answer that question. Like how did we actually lose our ability to give people social mobility of the kind that we at least purport to protect and how do we lose sight of the ability to protect our most vulnerable people?

Those issues feel not just relevant on a domestic basis, but also for how the rest of the world thinks about the United States. And I feel like I've got a hand in that process of it kind of feels like something I need to do.

Tweets of the Week

Thread

Great interview, Jordan. Just got an annual membership on https://www.patreon.com/ChinaTalk