Filling the Foundational Chip Gap

How to Tariff Right

Last year we ran an essay contest exploring policy solutions to China’s growing dominance in foundational chips. Today we’re running another entry along these lines by Alasdair Phillips-Robins. He’s a Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and from 2023 to 2025 served as a senior policy advisor to Gina Raimondo.

China is on track to control the global foundational chip market, a key chokepoint for huge swaths of the U.S. economy. Foundational semiconductors are produced on older processes, but they are essential to almost every modern electronic product. Unless Washington and its allies act soon, control over foundational chip production would hand Beijing a new economic weapon it could use against the United States in a crisis. A chip shutoff would make this year’s rare earth crisis look like child’s play.

There’s no single answer to the threat, but the United States should start by hitting products containing Chinese chips with a novel kind of tariff, known as a component tariff. This tariff would apply only to the value of the Chinese chip inside the product, not the total value of the item being imported to the United States. Washington will do even better if it can get its allies and partners to act against Chinese chips in their economies, too.

Component tariffs would have three big advantages:

They won’t spike consumer prices: conventional tariffs, like the ones Trump has said he’ll put on some chip imports, raise prices for American manufacturers and consumers. But because foundational chips typically cost little (often a dollar or less) relative to the finished product, a component tariff would have little effect on consumer prices while causing companies looking to save every dollar on parts to turn away from Chinese suppliers.

They get ahead of the problem: most chips in American electronics aren’t made in China, but Chinese production is ramping up. A component tariff would discourage U.S. manufacturers, and foreign ones that sell in the United States, from switching to Chinese foundries when they come online. Foundry relationships are sticky, so getting out in front is the best way to stop Chinese market dominance.

They can be applied to other industrial inputs: Implementing a component tariff won’t be easy — it hasn’t been done at scale before — but getting it right would unlock a major new tool in the fight for fair trade with China over everything from batteries to minerals.

The Everything Chips

Foundational chips are used in vehicles, communications equipment, military systems, and other critical infrastructure. Even devices that contain cutting edge chips, such as phones, rely on numerous legacy chips. It was shortages of these chips during the pandemic that idled factories, emptied shelves, and left unfinished vehicles sitting on production lots.

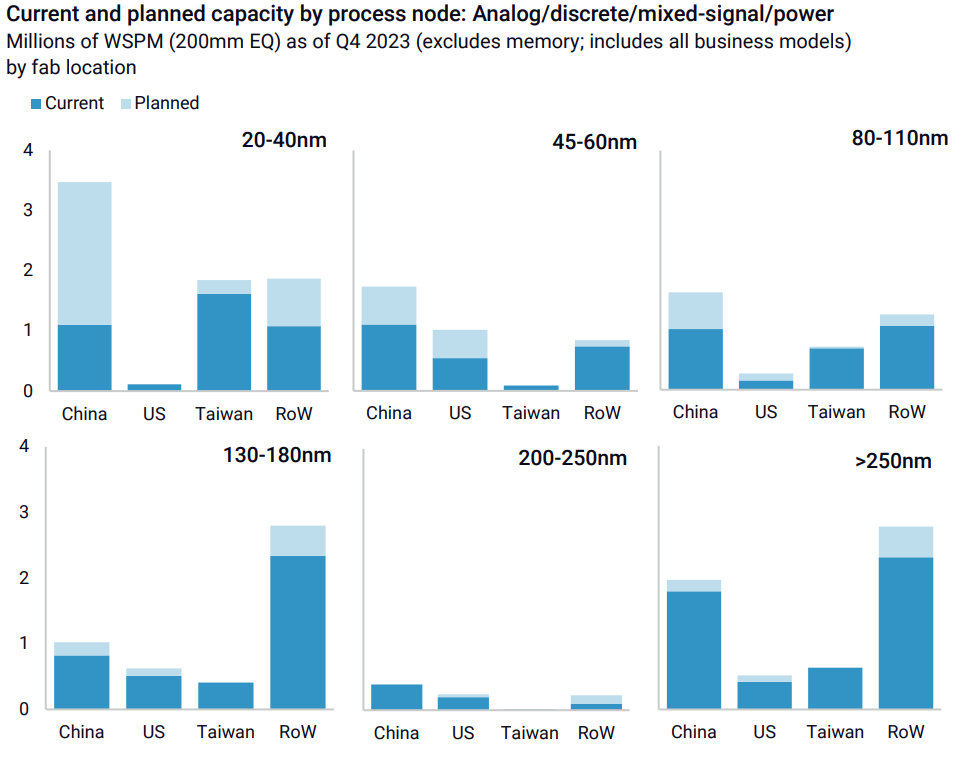

The CHIPS Act was meant to prevent a repeat of this shortage, but only about $4 billion of the act’s $39 billion in manufacturing incentives has gone to foundational production. Meanwhile, China is spending tens of billions in subsidies for foundational chip producers and is on course to raise its share of global production capacity from around 30 percent today to more than 40 percent by 2030, with a majority of capacity at some critical nodes.

Heavy reliance on Chinese production would be an economic and security nightmare. Many legacy chips are specialized, and once the expertise and facilities to produce them have been lost, regaining them will be slow and expensive. As subsidized Chinese prices drive out competitors, chip buyers will struggle to find alternatives. Chinese-made chips will become embedded in American military systems and critical infrastructure, raising the risks of espionage and sabotage.

If supply from China gets cut off in a trade confrontation or a military crisis, economic activity in the rest of the world will grind to a halt. The result would be a repeat of the recent fight over rare earths, or the pandemic-era shortage, on a far wider scale. As soon as rare earths stopped flowing, Ford CEO Jim Farley began telling the White House that his production lines were shutting down. In a chip fight, the same will be true of dozens of industries, from vehicles to planes to wifi routers.

Beyond providing some CHIPS Act funding, U.S. policymakers have done little about the problem. In 2018, the first Trump administration imposed tariffs on imports of Chinese chips (the Biden administration kept them in place). But these tariffs haven’t achieved much, because they apply to the overall product being imported, not at the sub-parts inside it, and almost all foundational semiconductors enter the United States inside other products. A company that imports phones, for example, pays the general tariff rate for the country where the phones were assembled, plus any specific tariff applied to phones; it doesn’t pay any extra if the chips inside the phone were made in China. Manufacturers have no incentive to use non-Chinese chips over Chinese ones.

How to Tariff Better

Trump has said he plans to put a 100% tariff on foreign chips, but these won’t capture Chinese chips any better than the original approach. Rather than doubling down on traditional tariffs, the Trump administration should turn to component tariffs. Unlike a normal tariff, these would be triggered by the presence of a Chinese-made chip inside any product imported into the United States. The tariff could either be a flat rate on the number of Chinese-made chips in the product — a dollar per chip, say — or it could be tied to the cost of the chips. For example, if Chinese producers offer chips at a 50% discount relative to U.S. and allied producers, a 100% tariff would offset the Chinese advantage, levelling the playing field for U.S. chip makers. Luckily, the administration has the perfect legal vehicles to impose these tariffs, in the form of two trade investigations, one into Chinese legacy chip production launched in late 2024, and a broader investigation of semiconductor imports begun earlier this year.

Opponents of tariffs point out that they often hurt the very constituencies they are meant to help, as they raise prices for manufacturers importing tools, parts, and raw materials. But a component tariff on legacy chips would be a rare exception to those problems. Because legacy chips are usually cheap relative to the cost of the overall product, often costing a few dollars or less per chip, a tariff would have little effect on ultimate consumer prices, but would shift the incentives for electronics manufacturers looking to save on the parts that go into their products. Crucially, because China doesn’t yet dominate legacy chip production, most chip buyers won’t have to go through the painful process of finding alternative sources of supply for their chips; they’ll just need to avoid switching to Chinese suppliers when new capacity there comes online. Even outside the United States, there’s plenty of foundational capacity in the EU, Japan, and Taiwan that can be scaled up to meet growing demand.

Component tariffs have another major benefit: they would force companies to truly understand their supply chains. A 2024 Commerce Department survey found that nearly half of U.S. chip buyers didn’t know whether their products contained Chinese-made chips — an unacceptable situation for U.S. national and economic security. Requiring companies to report the sources of their chips to CBP when they import products would help change that. Self-reporting would make the tariff vulnerable to fraud, but it would be backstopped by CBP investigations to catch wrongdoers, and a legal requirement would give companies the push they need to finally map their supply chains. This is the same model the U.S. government has used in enforcing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which bans the import of products made with forced labor in China’s Xinjiang region. As with chips, CBP can’t tell from looking at a product whether it was made with forced labor. But importers are responsible for ensuring their supply chains are free of Uyghur abuses, and CBP can investigate alleged violations.

Implementing a component tariff would take time and money, especially as CBP hasn’t applied one at scale before (a few products, like watches, are tariffed based on their components, but it isn’t common). Luckily, CBP just got a big influx of cash from the One Big Beautiful Bill and plans to hire 5,000 new customs officers over the next four years. As for revenue, manufacturers that responded to Commerce’s 2024 survey imported about $1.5 billion in Chinese chips each year, and in total represented about one-sixth of global chip sales. That suggests a 100% component tariff on Chinese chips could bring in a few billion each year, enough to offset the cost of implementation without upending the overall chip market.

Component tariffs would also send a valuable market signal. Because chip production in China is still ramping up, the U.S. government can get ahead of the problem. Even an imperfectly enforced tariff would get electronics manufacturers to think twice before turning to Chinese chip makers. Chip supplier relationships are sticky — products are made to exact specifications, and switching to a new producer can be costly — so preventing Chinese firms from locking in customers is the easiest way to win the chip war.

Legacy chips won’t be the last sector where component tariffs come in handy. China is working to dominate other manufacturing inputs, like batteries and drone parts, and the United States will need tools to respond. Getting the bureaucratic machinery to work with component tariffs now will give the U.S. government another option when it confronts similar problems in the future.

A component tariff will be especially effective if the administration can bring along its partners, including the European Union and the G7, which have both expressed concern about Chinese semiconductor overcapacity. Washington has a bad habit of scrambling to address Chinese industrial targeting after a critical U.S. industry has already withered away. Legacy chips offer a rare chance to intervene before it’s too late.