How China Courted Iran

A fraying marriage of convenience

Happy New Year! This is your reminder to fill out the ChinaTalk audience survey. The link is here. We’re here to give the people what they want, so please fill it out! ~Lily 🌸

Anti-government protests are tearing through Iran, and the regime has responded with an internet blackout of unprecedented scale. Even Starlink access has been disrupted, thanks to military-grade jammers that may have been supplied by China or Russia. But between China’s insubstantial responses to the bombing of Iranian nuclear sites and Maduro’s kidnapping, has Tehran started to doubt the benefits of partnering with Beijing?

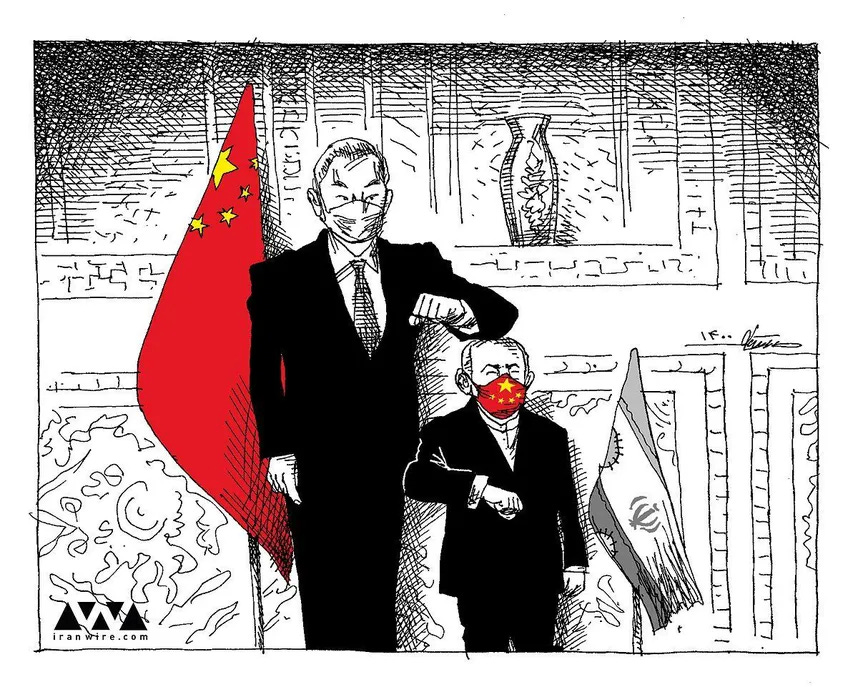

For two countries so closely aligned, China and Iran don’t have all that much in common. In theory, Iran’s theocratic government shouldn’t look too kindly on China’s treatment of Uyghur and Kazakh muslims in Xinjiang, and Chinese academics are often skeptical of the reputational costs that come from aligning with a state sponsor of terrorism.

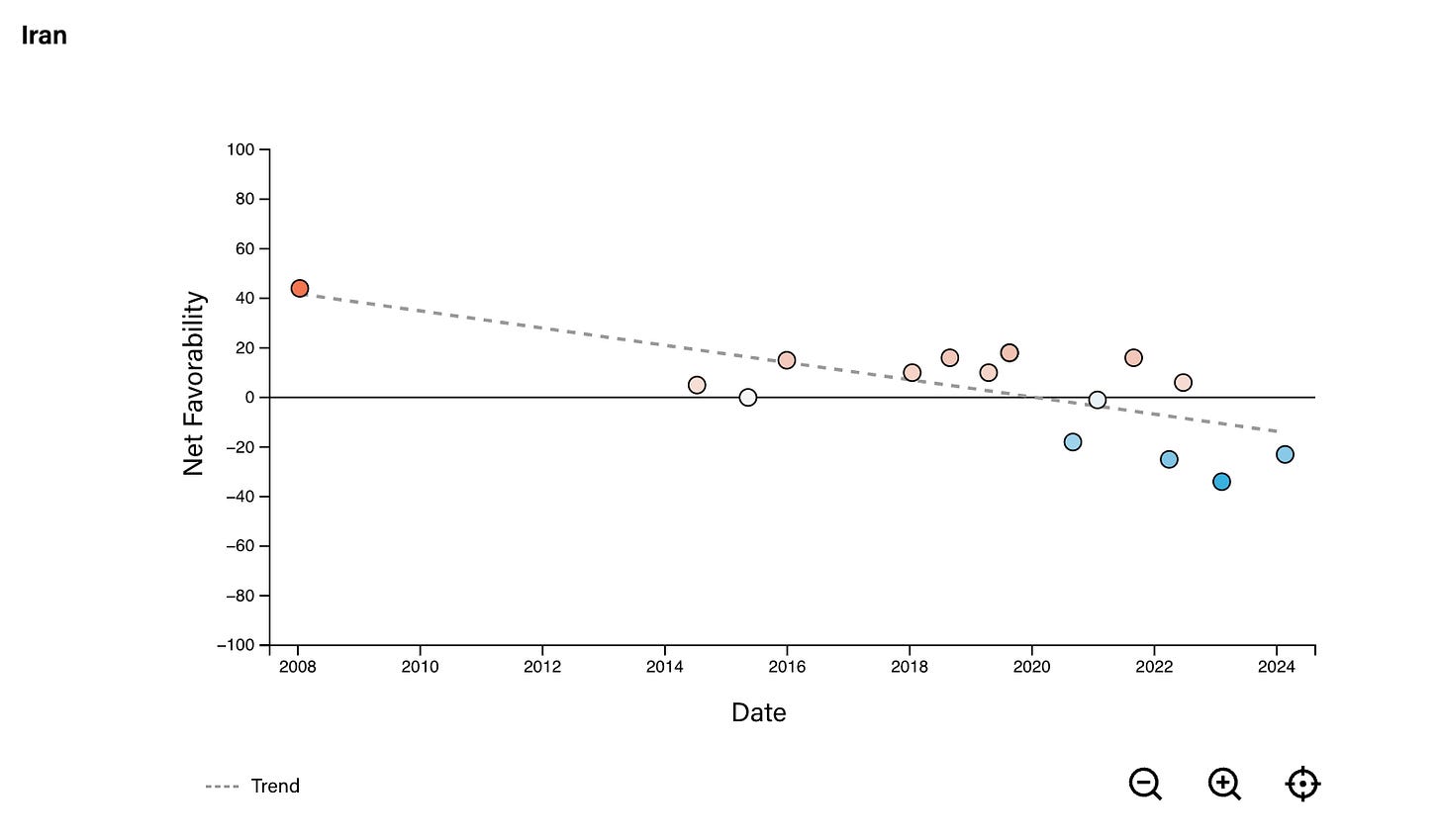

While their relationship has been punctuated by scandals, China has taken them in stride, using a combination of material incentives, narrative control, and appeals to specific power centers within Iran to manage relations, even as China’s favorability declines among the Iranian people.

Today, we’ll explore how China forged a relationship with Iran, how the two countries manage tensions, and the extent to which Beijing can influence Iran’s decision-making.

«بدعهدم اگر ندارم این دشمن دوست»

“With friends like these, who needs enemies?”

Post-Revolution Tension

After the Islamic Revolution in 1979 — during which protesters shouted slogans denouncing foreign influence, such as “Neither East nor West” («نه شرقی، نه غربی») — Iran’s new government was distrustful of foreign powers that had close relations with the Pahlavi dynasty. This included China, which backed the Shah since Iran and China had a common enemy in the Soviet Union. Chairman Hua Guofeng was among the last foreigners to meet with the Shah before he was deposed by the revolution.

The story of modern relations begins with the personal charisma of Zhang Guoqing 张国清, who has served as Vice Premier of the PRC since 2023. Beginning in 1987, Zhang Guoqing spearheaded China’s weapon sales to the Middle East, working as a project manager of the arms exporter Norinco. These were the final years of the brutal war between Iran and Iraq, and China capitalized by selling arms to both sides (a fact which Beijing denied at the time). Between 1987 and 1989, Zhang was promoted twice for his work at Norinco. After the end of the war, he moved to Tehran and lived there until 1993, reportedly teaching himself some Farsi to help close deals. In 2004, he cinched a US$836 million deal that saw Norinco build Tehran’s Metro Line 4, outcompeting bidders from Germany, South Korea, and even Iran itself. This was China’s largest ever foreign contract engineering deal at the time.

When the UN Security Council levied sanctions against Iran (which China did not veto), China designated the Bank of Kunlun to handle Iran-linked payments and thereby shield large Chinese banks from secondary sanctions. This strategy worked from 2009 to 2018, and Kunlun processed billions of dollars in payments for Iranian oil. That changed after Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou was arrested for Huawei’s violations of US sanctions on Iran. Today, China uses a system of oil-for-goods bartering that has flooded Iranian markets with cheap manufactured products. To avoid being blacklisted by the US, Chinese buyers use a “dark fleet” of tankers — ships that turn off transponders and conceal their movements — to carry Iranian crude. Ship-to-ship transfers at sea and falsified documentation are common; upon arriving in China, Iranian crude is often rebranded as oil from Malaysia or Oman before being sold to independent refineries known as “teapots.” It’s estimated that China purchased 77% of Iran’s crude oil in 2024, extending a crucial economic lifeline to a regime with few international partners.

Case Studies in Damage Control

Against the backdrop of competition with the United States, Iran and China might seem like natural partners. China has sweetened the deal with economic engagement and technology transfer, and sent top propagandists to help smooth over scandals. But if China asked, would Iran stop supporting Houthi attacks on trade in the Red Sea?

To answer this question, we need to understand how much exactly Iran gains from China.

RMB to Rials

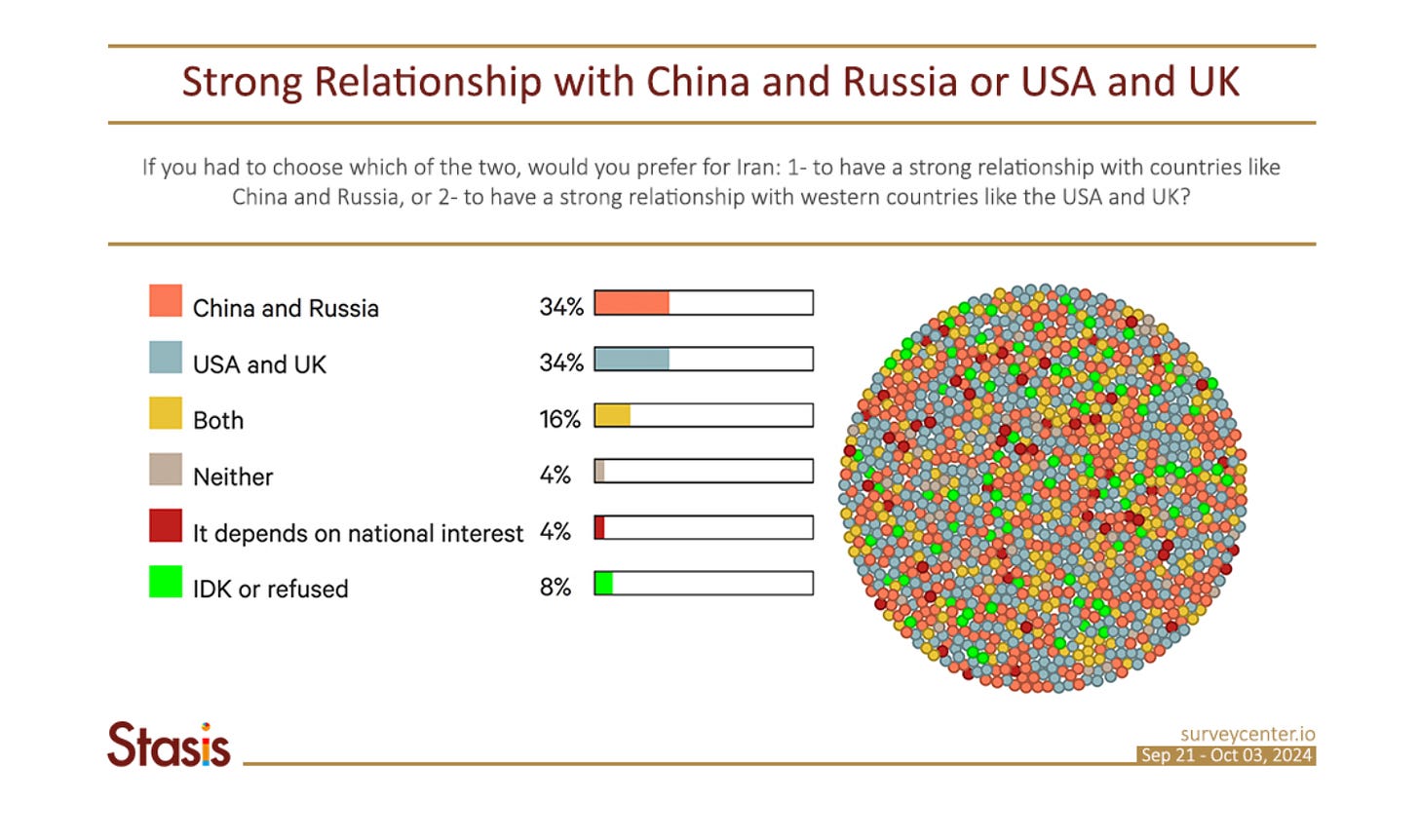

In 2021, Iran and China announced a 25-year partnership agreement that was met with skepticism and protests by the Iranian public. Iranian critics are quick to point out that the text of the partnership agreement still has not been publicly disclosed. As explained by Tehran-based journalist Mohammad Hashemi:

For more than a decade, inexpensive and low-quality Chinese consumer goods—ranging from vehicles to homeware—have flooded Iranian markets, putting local manufacturers and artisans out of business. Although commerce with China has also brought significant economic benefits—the average Iranians can afford goods that they would not have been able to under an autarkic system—Iranian businessmen and consumers alike have voiced persistent complaints about unfavorable terms of trade, shoddy products, and broken promises made under the shadow of a crippling U.S. sanctions regime. While acknowledging China’s growing military and economic might, many Iranians have associated China with censorship, the violent suppression of dissents, and a set of exploitative and self-serving policies. Domestic critics of Beijing also note that the country sided with the United States and its European allies at the UN over the issue of Iran’s nuclear program between 2006 and 2010. Chinese companies have also been involved in exploitative development projects that have severely harmed Iran’s environment.

To evade U.S. sanctions, Iran has provided China with immense quantities of heavily discounted oil. Instead of providing hard cash, however, China has paid for Iranian oil through the provision of cheap consumer items.

The deal was controversial on the Chinese side as well. Ma Xiaolin 马晓霖, Professor at Zhejiang University of International Studies and Middle East specialist, has been especially critical of China’s relationship with Iran:

[P]eople can’t help but worry that if China is so closely tied to Iran, it will further “offend” the United States and many Middle Eastern countries.

…

For China, the economic aspect is particularly worrying. Will the US’s “long-arm jurisdiction” and “secondary sanctions” further harm Chinese companies and capital due to the close trade and investment relations between China and Iran? In this regard, China’s ZTE and Huawei have suffered enough from the US.

…

Some Iranian nationalists believe that the Iranian government is selling out national interests [by cooperating with China].This statement is annoying: Who is this agreement more beneficial to? In my opinion, although it is mutually beneficial, it is obviously more conducive to improving Iran’s strategic environment and economic difficulties. Currently, no country dares to promise large-scale investment in Iran like China, and it is for a long period of 25 years and a large amount of US$400 billion. This is undoubtedly a strategic endorsement for the Iranian government to stabilize the economy and politics.

…

Of course, perhaps they are indeed worried that China will “control” Iran in the future with so much investment? However, the fact is that China bears greater risks.

Nonetheless, China’s investments in Iran grew to US$3.924 billion by the end of 2023 (although this is peanuts compared to China’s other regional investments — for example, China invested $22.5 billion in Saudi Arabia and $13 billion in Iraq between 2018 and 2022).

Under the 25-year pact, six Iranian automakers (including Iran’s two largest) have agreements with Chinese companies to co-produce electric cars. In 2023, nearly 40% of China’s total exports to Iran were vehicles and vehicle components. That prompted Iran to impose a 100% tariff on electric vehicles in 2024, crushing the hope that Persians would be major buyers of Chinese EVs. While Tehran has eagerly agreed to joint ventures like these in pursuit of technology transfer, jobs for Iran’s highly educated population, and a path to reduced air pollution, there is still little incentive to buy an electric vehicle in Iran for now. Charging infrastructure is poor and cheap gasoline is abundant (gas can cost as little as 1,500 toman per liter, or about 36¢). Still, this kind of highly public joint venture is a key part of the Sino-Iranian relationship — even as Tehran couples cooperation with protectionism to appease local industry.

Narrative Control, Xinjiang, and the Virus from Wuhan

In 2020, as Tehran battled deadly outbreaks of the new coronavirus, China was simultaneously facing criticism at the UN and ICC for its treatment of Uyghur muslims in Xinjiang. Relations hit a low point when Iran’s Ministry of Health accused China of lying about the seriousness of COVID and its origins. Maysam Behravesh and Jacopo Scita summarized the incident in the National Interest:

[W]hen the coronavirus public health crisis had reached a critical point across Iran, health ministry spokesman Kianush Jahanpur took to Twitter to denounce Beijing for “mixing” science with politics and producing inaccurate information about the nature of the novel coronavirus threat. “It seems China’s statistics were a bitter joke as many in the world thought this was a flu-like disease with a smaller mortality rate,” he said at a news conference on the same day. “All these [measures] were based on reports from China, [but] now it seems China played a bitter joke with the world.”

Chinese ambassador’s public response was unconventional. “The Ministry of Health of China has a press conference every day. I suggest that you read their news carefully in order to draw conclusions,” Chang Hua [常华] wrote, indicating the extent of influence Beijing wields in the Iranian corridors of power. Unsurprisingly, the rhetoric evoked memories of “capitulation” to foreign powers among many Iranians—which the Islamic Republic had pledged to end after the 1979 revolution—and provoked an unprecedented public outcry over Beijing’s condescending and “colonialist” treatment of Iran.

Yet, the Iranian foreign ministry’s reaction awas one of unmistakable appeasement. In a tweet that was warmly received by the Chinese ambassador, Iran’s foreign ministry spokesman Seyed Abbas Mousavi commended “Chinese bravery, dedication & professionalism” in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic and stressed that Iran “has always been thankful” to China.

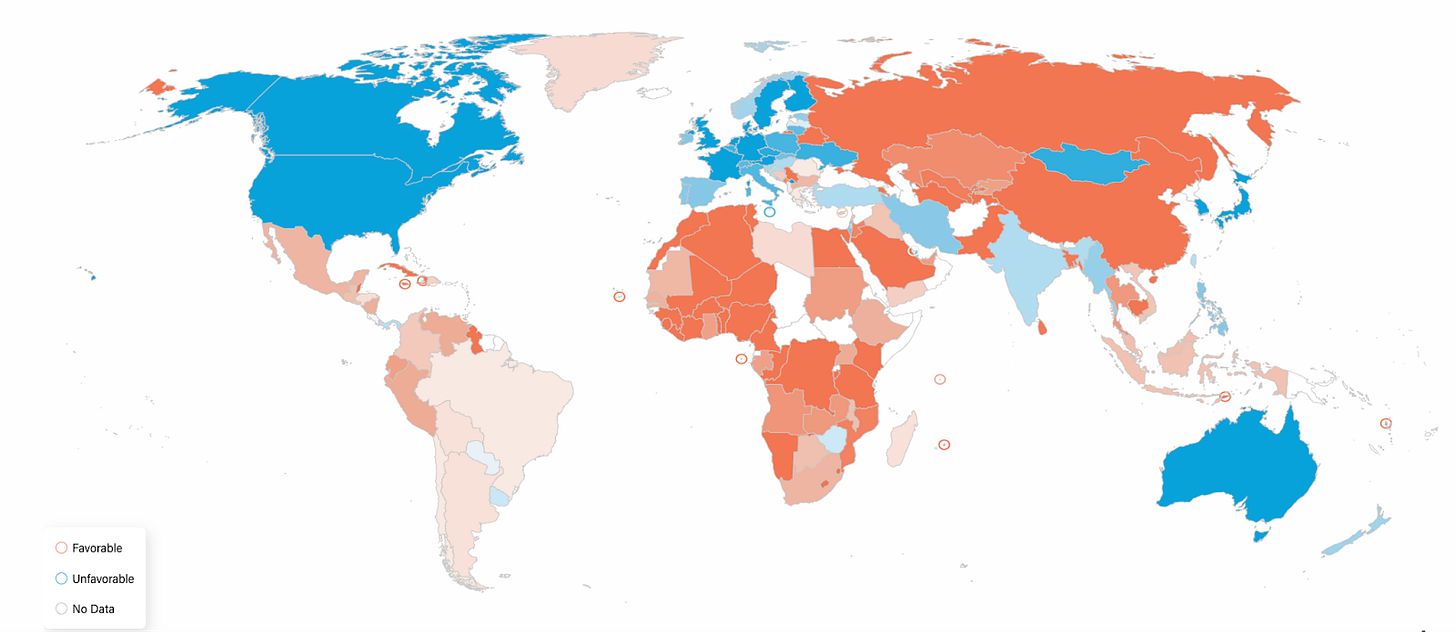

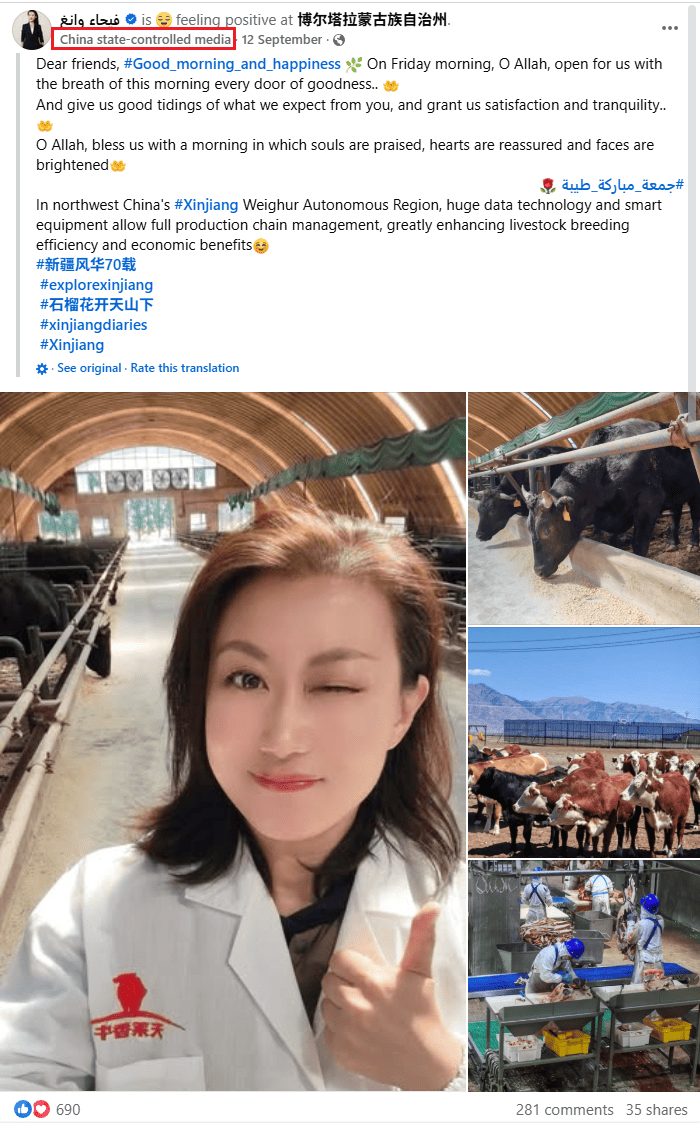

China began to roll out damage control measures alongside economic cooperation by sending shipments of masks, COVID tests, ventilators, and eventually vaccines to Iran and other Middle Eastern countries, as well as launching a propaganda campaign about Xinjiang. This bet paid off in 2020, when not a single Muslim-majority country voted to condemn China’s use of re-education camps for Uyghurs. Instead, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain all signed a letter in support of China’s Xinjiang policy.

How did the Chinese line succeed so completely?

The narrative on the Uyghur issue is essentially, “everyone’s war on terror is their own business.” It’s not really a surprise that Iran was able to look the other way and accept this narrative, given that Tehran isn’t exactly a bastion of human rights.

To sweeten that grim reality, both official and unofficial channels have spent resources propagating feel-good stories about Beijing’s development initiatives in Xinjiang. For example,

In March of 2021, as Tehran was preparing to battle a fourth wave of COVID caused by Nowruz holiday travel, Iran’s then-ambassador Mohammad Keshavarzzadeh visited Xinjiang to court Chinese officials and tweet about Uyghur food. The resulting Twitter roast failed to alter his positive convictions about the region.

Around the same time, Iran’s state-run IRIB aired interviews with Chinese diplomats defending the camps in Xinjiang as mere vocational centers.

In May of 2024, Iran’s ambassador to China met with Xinjiang party secretary Ma Xingrui 马兴瑞 to discuss transportation infrastructure and bond over how old their civilizations are.

China’s state-run international news platform CGTN frequently publishes stories about Xinjiang in Persian. These include write-ups about smart agriculture, renewable energy, and digitization paired with brightly colored pictures. Similar stories are often posted on CGTN’s Arabic social media — that’s not aimed at Iranians obviously, but given that Tehran just lifted its Instagram ban, I wouldn’t be surprised if CGTN rolls out Farsi social media pages sometime soon.

In exchange for silence, China has cooperated with Iran to oppose the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism, including by helping to mediate tensions after Iran conducted strikes on Baloch separatists in Pakistan in 2024. This is a tried and true playbook that China has been using since the 1990s — after the collapse of the Soviet Union, China offered proactive territorial concessions to the newly independent Kazakhstan in order to guarantee Xinjiang was starved of support from pan-Turkic or pan-Islamic sympathizers in Kazakhstan.

Picking Battles

Chinese companies have been embroiled in a number of environmental scandals in Iran. Drilling by a Chinese oil company damaged the al-Azim wetland in 2021, and trawling by Chinese ships in the Persian Gulf led to intense public backlash in 2019. Behravesh and Scita write in 2020:

“The public outcry over the issue gained so much traction that the IRGC was compelled to intervene and limit the operations. “I came to believe that there is a mafia behind bottom trawling [by] Chinese ships,” General Alireza Tangsiri, commander of the IRGC Navy warned in February 2019. “One cannot close their eyes to these realities and we have to stand up firmly against those who seize bread from the table of traditional fishermen.” Echoing similar criticism, Iran’s Minister of Culture Mahmoud Hojjati pointed out in November that Chinese trawlers operating in the southern waters have not secured an official permission from the Iranian government. Yet, it seems the practice still persists”

China’s response to these scandals has been to cultivate closer ties with the Iranian mullah regime, working to become an invaluable partner to the Iranian government even as negative sentiment swells among the Iranian public. This strategy is exemplified by Beijing’s decision to arm Iran’s riot police in the wake of protests following the murder of Mahsa Amini in 2022. Professor Nader Habibi explains in 2023:

First, the Islamic regime has relied heavily on Chinese digital technology and surveillance software to identify and arrest protestors. Face recognition software in particular was very effective in helping the government apprehend large numbers of people. The same technology has been used to identify women who defy the hijab rules. The government has inflicted severe economic and social punishment on these women, such as lack of access to government services and heavy fines. It also uses these technologies to identify businesses and government offices that offer services to women that violate the hijab rules. Street cameras have been used to identify stores and restaurants that have served poorly covered or unveiled women. In addition, China is the main supplier of riot control and urban warfare weapons to the government of Iran.

Huawei has been partnering with the Iranian government to provide protest-busting tools since at least 2011. In this way, China’s slipping favorability rating is a feature, not a bug, of its relationship with Iran.

A Marriage of Convenience

Thus far, China has refrained from flexing its influence over Iran — sure, China has bribed Iran into silence on the Uyghur issue, but using carrots to reward Iran for passivity is fundamentally different from threatening to withhold economic engagement unless Iran changes course. That’s why China has only pressured Iran to rein in Houthi attacks on Chinese shipping vessels in the Red Sea.

This also explains why China didn’t feel the need to offer any material support after the US bombed Iranian nuclear facilities — both parties are aware that their alignment is contingent on convenience, not trust or goodwill.

Sino-Iranian relations are a blueprint for understanding China’s broader messaging goals with respect to the Global South. Since China’s growth strategy is essentially to crowd out burgeoning manufacturing centers in developing countries, these tensions will be inevitable as China deals with international partners. The Iran case indicates that China will respond to such charges with cheap goods, infrastructure deals, no-questions-asked surveillance technology, and diplomatic support on even the ugliest of foreign policy issues — but it remains to be seen how many countries will take that deal.

The Architecture of a Crisis Manufactured by Hostile Foreign Powers.

An exclusive exposé on the hidden forces, intelligence networks, and propaganda machinery fueling turmoil in Iran.

https://felixabt.substack.com/p/the-architecture-of-a-crisis-manufactured