How Corruption Works in China

Plus: How Not to Cook Rice, The Melian Dialogue, the NBA and Paris Hilton

The ChinaTalk podcast has had a great run of recent episodes. One particular standout was with Prof Yuen Yuen Ang on her new book China’s Gilded Age. We dove into the paradox of how modern China has prospered in spite of vast corruption.

Listen here on Spotify, iTunes, or YouTube below.

Corruption and competence are two things that don’t just coexist but are mutually reinforcing. If you want to be a corrupt official you have to be competent, you have to show that you’re ambitious and show [businesspeople] that you’re the next rising star to find people to sponsor you. If you want to be a competent official and you want to deliver projects you, in a sense, need corruption, because you need business people to get things done.

In democracies, politicians can’t just exist on their own, they need campaign finance, they need funders behind them to do their work. Campaign finance is institutionalized and legalized in this country, but I see it as a parallel. But in China, politicians also need campaign finance.

The few officials who don’t play the game and just try to stay clean end up getting eaten up and spit out by the system. In a particularly pathetic example, as Party Secretary of Shenyang and Hengyang, Tong Mingqian didn’t smoke or drink, took no bribes himself, and always ate packed dinners from the government cafeteria instead of feasting at banquets. However, he held so little sway that according to state media “lacking audacity and authority, even county leaders don’t take him seriously.”

One day, a few businessmen who failed to get elected to the Provincial Congress after bribing Tong’s subordinates barged into his office and demanded compensation. Instead of throwing them in jail, or at the very least telling them to get lost, he tried to get them their money back. This incident clearly got people talking and ended up leading to a charge of negligence and dereliction of duty.

That said, his wimpiness did merit him a short jail sentence of six months, earning him the dubious honor of being the first senior-level official caught up in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign to earn release.

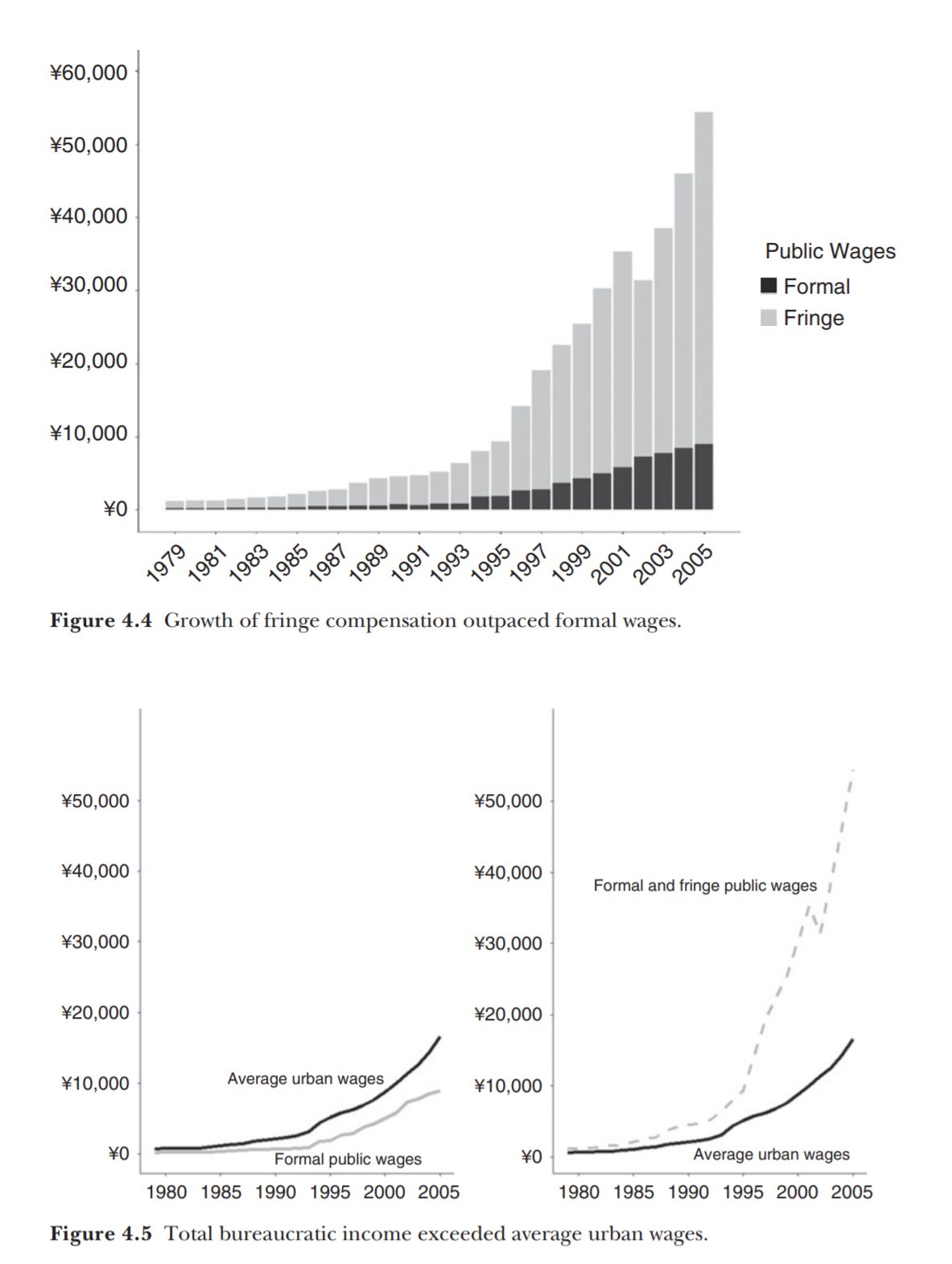

The book features a neat chart that breaks down the different types of corruption seen around the world and argues that the predominance in China of access money has allowed rapid growth in spite of massive corruption.

Why did access money come to be the dominant paradigm in China instead of the grand theft seen in Russia or the speed money predominant in India? We run through a multitude of reasons. First, we discuss how Deng got party officials to recognize that they could benefit from the success of economic liberalization, and how the continuity of CCP rule helped avoid a post-USSR-style firesale of assets. Then we go into the details of Zhu Rongji’s reforms that helped uproot petty theft, speed money, and to an extent grand theft, leaving access money as the main channel for cash to flow through the system.

Next, we talk about how the fact that compensation is, through fringe benefits, tied to growth keeps the low-level officials from squeezing the lifeblood out of private markets. Getting a bureaucracy whose leaders in the 80s and 90s were trained to run a centrally planned system was not a straightforward task. Trading out petty theft for access money is a serious chicken and egg problem, as you need to see colleagues in the township across the river upgrading their houses and their young men affording marriages thanks to their 12% growth.

My sense is that the utter poverty coming out of the Mao years helped market-driven reform. Mao’s economic policies were so terrible that A. bureaucrats up and down the system were convinced that things needed to change and few had much to lose since the country was so poor and B. anything they did couldn’t help but lead to rapid growth at least in the short term since growth was so suppressed in the 50s-70s. In contrast, Russia by the late 80s already provided a middle-class lifestyle to most of its citizens, so there were far more entrenched interests to overcome to execute reform and much more to be plundered during liberalization.

Chart by Bert Hofman (prettier visualization here). With the world growing at about 5% a year in the decades after WWII, China basically didn’t grow at all while Mao was still alive.

GDP per capita in the late USSR was 5x higher than in China.

In researching for the podcast, I stumbled on an Atlantic article from 1994 also entitled also China’s Gilded Age, in which a Chinese national who had been abroad since 1985 comes back to the mainland and reflects on the changes he saw. A few fascinating excerpts:

Even some of my relatives have become millionaires. A distant cousin who was a high school teacher until 1986 told me modestly that he had made "a little money" by opening a factory that produces bristle brushes for export to America. He drove me to his new summer house in his new Mercedes-Benz 500SEL, one of his three luxury cars. "This is China's Gilded Age," a former colleague of mine commented sarcastically. "These Chinese Carnegies and Rockefellers are more successful than their American counterparts -- they made more money within a shorter time."

In 1985, when I was last in China, the campaign against "spiritual pollution" was still under way, and it destroyed the careers of many intellectuals. One of my colleagues in Nanjing was sent to the countryside to receive "re-education" for his "unhealthy soul." He was accused of looking closely at the breasts of a woman student while he talked excitedly about graphic sexual portrayals in the fiction of Saul Bellow. Now the government seems to put fewer restrictions on popular culture and even risqué material from the West. In a hair salon a few blocks from my old home in Yangzhou glossy posters of naked girls cover the walls. Entering the shopping center of Jinling Hotel, in Nanjing, I was astounded to see a Playboy Bunny calendar welcoming customers. I was particularly struck by the sight because at Occidental College, where I have been teaching, there was a heated debate among students over whether the magazine should be removed from the college library.

A friend of mine who was a classicist by training, and who liked to argue with me about the origins of parliamentary democracy, has become a cosmetics salesman -- a job that I can hardly associate with his background and interests. When I mentioned this, he laughed. "Well, I have taken an indirect course to fight for democracy," he said, "because the growth of independent wealth, whether legitimate or ill-gotten, will surely erode the Party's control of the people."

The widespread corruption in China reflects a deep social, political, and psychological crisis in the nation. The gunshots at Tiananmen Square marked the end of the revolutionary phase of the Communist movement. Chinese leaders now openly acknowledge that the Party has changed from a "proletarian vanguard" into a ruling body. As a result the Party rank and file feel that they are no longer restrained by orthodox ethics. Many see the economic pluralism as providing them with an opportunity to loot. A fear that economic reform may falter at any time and a lack of confidence that the society will remain stable over the long term further impel the rush to get rich quick. Mao's slogan "Serve the people" has been thrown away, and the new motto for Party cadres is "Make the best use of power you can while still in office."

Graft and the loosening of controls allow the entrepreneurial spirit of those with ability to flourish. Moonlighting often brings people more income than their official pay. With their extra money ordinary Chinese can now display their personalities and reclaim their private lives. Perhaps this is, why public outrage over corruption is not so strong as abroad I had heard it was. There is even a rather tolerant attitude toward graft, especially among the professionals who have benefited from the market economy. In their eyes, corruption is inevitable in the transition from totalitarianism to authoritarianism. "Corruption is a price that China has to pay for the changes from a centrally planned economy to a market system -- it is the grease that can lubricate the political machine in a changing society," an economics professor in Nanjing preaches to his students.

A popular ballad sums up the situation nicely: "Of the 1.2 billion [people], one billion are corrupted. We join forces to cheat the Party and government." A close friend of mine said, "As long as it brings along changes and prosperity, it is tolerable. In any case, I'd rather live in a corrupted but free and prosperous society than a purified but stifling and stagnant land."

Thanks for reading. Consider supporting ChinaTalk here.

China Twitter Tweets of the Week

They didn’t teach me this in HSK 5…

ChinaTalk a few months back ran a translation of his most recent essay that got him in trouble.

What’s darker, this (Chongzhen Emperor for the uninitiated)

or this?