RAND's Jeff Alstott on Facts and Policymaking

AI, Energy, and How to Matter in DC

Jeff Alstott is the fairy godfather of D.C. AI policy. He’s the founding Director at RAND’s Center for Technology and Security Policy (TASP). He worked at the NSC, NSF, and IARPA. He has a PhD in Complex Networks.

We discuss:

How spreadsheets and tables on computer chips and energy policy change White House and Pentagon decision-making.

Why AI companions could be as normal as having a phone or mitochondria in your cells.

The risks of hacked AI “best friends” and emotional manipulation at scale.

The benefits and trade-offs of AI-augmented decision-making in high places

Have a listen in your favorite podcast app.

Why Facts Still Matter

Jordan Schneider: We’ll start with a meta question. What is the point of facts in technology and national security policy?

Jeff Alstott: The point of facts is really the point of analysis writ large. Analysis is most critical for lowering the activation energy required for a policy to be selected and enacted.There are many policies that could be enacted, and for any given policy, it’s useful to consider how much activation energy exists for that policy to get enacted.

In a democracy like the United States, this involves some amount of political will, and different actors have different policy budgets, whether political budgets or otherwise. They may be able to take actions that have higher activation energy, but in general, we would all agree there are policies that are easier for policymakers to pursue versus harder for policymakers to pursue. Analysis is one of the things that either helps the policymaker decide upon a given policy or makes the argument to others for the policy, which then lowers the activation energy for them selecting that policy.

Jordan Schneider: Some would say that we are in a post-truth, post-facts era where charts and data don’t matter. I don’t happen to agree with that, but I’m curious about your response to that line of thinking when looking at the American political system today.

Jeff Alstott: I don’t consider it to be notably post-facts or post-truth or post-data compared to randomly selected other periods of American history. I do think that we have radically diverging attention, which is often related to diverging values but also diverging mental models of the world. A lot of disagreement stems from which of those we should prioritize and which we should focus on first. People often confuse differences in focus, attention, or prioritization with differences in attending to “the facts.”

That doesn’t mean that facts are always attended to — not at all. I’m not asserting that. Importantly, it also doesn’t mean that “the facts” are actually the facts. There have definitely been periods over both the past several years and past several decades where “the experts” have asked people to “trust the facts,” and then it turned out that the facts were wrong because science can be hard and we have error bars in our analyses. But I don’t think that we’re wildly out of step with previous eras in American history on this front.

Jordan Schneider: One interesting thing about technology and AI policy in particular is that the new variables at play and the new facts that senior policymakers in their 40s, 50s, and 60s are having to confront are different from debating Social Security, Medicare, or the national debt. With those issues, people have had years and decades to develop mental models for understanding them. At one level, this is frustrating because maybe you’re just at a deadlock and no one can agree to move forward on anything. But it also provides a really interesting and exciting opportunity for a collective like RAND to take young talent, get them to the knowledge frontier, push past it, and inform these busy policymakers who need to grasp these new concepts for which there isn’t necessarily a lot of built-in context.

Jeff Alstott: Absolutely agreed. This is not new. It’s definitely happening with AI right now, but anytime there’s been a new era of technology, there’s an education process and a getting-up-to-speed process. Those people who anticipated this issue — whatever the issue is: AI, internet policy, vaccines, or even foreign policy — become valuable.

There was an era where we didn’t think we were going to be doing anything in Vietnam, and then we were doing things in Vietnam, and the people who knew about Vietnam suddenly became very valuable. People who anticipated, “Hey, maybe we should know things about China,” have been at the tip of the spear for understanding things about China writ large, but also on China and tech.

There’s immense value for people looking ahead into the future and placing bets on what is going to matter, then spending the time ahead of time to get smart on whatever issue set is going to be coming down the pike. At TASP, we explicitly try to skate to where the puck is going. We anticipate what’s going to be happening with frontier AI capabilities, inputs, proliferation, etc., and say, “Oh, a policymaker is going to ask this question in six months or six years.” We do the work ahead of time so that when the moment arrives, we have the answers there for the policymakers.

Jordan Schneider: I’m glad you brought up Vietnam, Jeff, because I think Vietnam and Iraq in 2003 are two examples where the country’s regional experts were not listened to in the lead-up to very consequential decisions. You have these folks making very particularist arguments about their domain, and the people who actually had the power, who were in the room where it happened, were applying their generalist frameworks to the issue.

How does and doesn’t that map onto what we’re seeing with AI today? I remember in the early days when we had Senator Schumer doing his “let’s listen to all the CEOs” approach. The amount of deference that you saw on behalf of senators and congresspeople to these CEOs and researchers was really shocking to me. They were all just like, “Oh, please tell me about this. I’m really curious” — which is not generally how CEOs of giant companies are treated by the legislative branch.

As this has gone from a cool science project to a thing with big geopolitical equities, the relationship that the companies and the scientists have to the people in power is inevitably going to change. From where you sit running this group of 50 to 100 analysts trying to tease out the present and future of what AI is going to do for the US and national security: what is that realization on the part of a lot of actors in the system that this is a thing we really have to take seriously and develop our own independent views on doing for the desire for facts and analysis?

Jeff Alstott: You’re completely right that the situation now for different policymakers trying to learn things about AI or decide what to do about AI is different from how it was some number of years ago when frontier AI exploded onto the scene. What you went from is a period where nobody’s staff knew anything to now where all the staffers have known for a while that they need to know about this. They have spent time reading, studying, and marinating in these issues. Everyone now has a take. There was a period where nobody or few people had a take, and now everybody has a take, rightly or wrongly. We’re seeing congealing in different ways.

I think of this somewhat in terms of spaces being crowded or not. We have definitely at TASP repeatedly had periods where we said, “Okay, we are working on X, and now it’s the case that there are a bunch of other think tanks working on X. We don’t need to work on X; let’s go work on Y. Other people have got the ball; other people can get it done.” It’s nice from a load-sharing perspective.

In terms of your question about how facts and analysis and their role change as the audience gets more acculturated to some topic area, I think it can cut both ways. It’s really unfortunate when your audience is deeply ignorant of every word you say — they don’t know anything about anything. You can see how that would be very dangerous from a policymaking perspective. Them having more familiarity and having staff with their own mental models of things enables more sophisticated conversations, considerations, and thus policymaking. It really does.

On the other hand, as I said, people have their takes, and it can be the case that people get congealed or hardened into certain positions. Now getting them out of a position if it’s wrong is a much different mental move. It can cut both ways.

How Facts Change AI Policy

Jordan Schneider: Ok, enough of this 10,000-foot stuff. Let’s jump into some case studies. Some longtime ChinaTalk listeners would know from the repeated episodes we’ve done with Lennart Heim talking about compute and AI and geopolitics, but you guys have been up to lots of other stuff. Jeff, why don’t you do a quick intro of TASP and then jump into one case study that you’re particularly proud of — how you guys have used analysis to forward a conversation.

Jeff Alstott: TASP is a team of between 50 and 100 people, depending on how you count, where our mission is tech competition and tech risks. It’s beat China and don’t die. That has predominantly meant frontier AI issues.

One great example was our work around energy and AI. This is about the amount of energy or power that needs to get produced domestically in the US in order to keep frontier AI scaling happening in the US versus elsewhere. It happens to be the case that the US currently hosts about 75% of global frontier AI computing power. But if that frontier AI computing power continues to scale up, we just do not have the electricity on the grid to keep those chips alive. The chips are going to get deployed elsewhere.

This was an issue that frontier AI companies had started murmuring about quite some time ago — both the companies that make the AIs, but more particularly the hyperscalers that make the computers that actually do this.

It took me a little while to realize this could be a really big thing. Sometime mid-last year, I put together a team of RAND researchers who know about energy and paired them with people who knew about frontier AI computing. I said, “We are going to need a table.” That table is going to be a list of all the energy policy moves that are possible within executive power. We’re going to need for each move the amount of gigawatts that it will actually unlock on the grid.

This is not about what sounds good; this is not about what fits a particular political ideology. It is about what are the moves that unlock the most gigawatts. You can then rank the table by gigawatts, and those need to be the policies that policymakers are most attending to, putting their energies towards.

That took on the order of a year to create. The report is out now (or in op-ed form). We’ve already been briefing the results to policymakers to be able to say, “Look, you think that you have a problem over here with supply chains for natural gas turbines. That is an example of a thing that is an impediment to domestic energy production in the US. But there are other moves that would produce far more gigawatts that actually turn out to be more available. That is to say, they don’t require international supply chains; they just require domestic deregulatory moves in terms of allowing people to make better use of their power production capabilities that are already on the grid and upgrading them.” That is an example of a case study.

Make Your Own Fray

Jordan Schneider: This is the type of work that I find exciting and inspiring, especially if I am a promising 24-year-old wanting to make a dent in the universe. There are so many policy problems which are intractable where facts and analysis aren’t really that relevant anymore. You are not really going to change Trump’s mind that tariffs are useful, or you are not going to change Elizabeth Warren’s mind that more government regulation in healthcare is going to deliver positive benefits.

But there are a lot of weird niche technical corners where I don’t think a lot of politicians or regulators have super strong priors when it comes to gas turbines versus deregulating transmission lines or what have you. You are very far from the Pareto frontier where you actually have to start doing really tough trade-offs when it comes to sending GPUs to the UAE or taking Chinese investment in X, Y, or Z thing or trading off chips for rare earths. You can color under that and push out the level of goodness that anyone and their mother who’s working on these policies would want. You could probably agree on that.

Doing that type of work, especially as you’re starting out in a career in this field, gives you a really great grounding. I think it’s a corrective as well. You’re consuming so much news which is about the fights that are intractable or are about value differences where the facts and analysis aren’t quite as germane to what the final solution could be. But there are so many weird corners, particularly when it comes to more technical questions about emerging technologies, where there are positive-sum solutions. You just need to go do the work to find them because no one else is.

Jeff Alstott: Absolutely agreed. I love your metaphor of coloring underneath the Pareto frontier. There’s a famous biologist, E.O. Wilson, who died a few years ago. I remember he has this guidance about careers, and he said when there’s a bunch of people all attending to a certain issue, it can create a fray. There’s a fray of conflict, and you can leap into the fray and try to advance things, or you can go make your own fray. That phrase “make your own fray” really stuck with me.

It happens to be the case that within policy, as it gets more like politics — as you describe, where there’s more and more attention to the issue, more people are knowledgeable about the thing — then the low-hanging fruits get picked, and then the remainder are things that are on that Pareto frontier. It becomes more about differences in values. Then indeed, the relative returns go up of trying to go make your own fray on a different issue.

Jordan Schneider: Especially from an individual perspective: Can you have fun? Will your work make an impact? You can have a higher degree of confidence that the time you are spending on the thing will lead to a better outcome on the thing versus figuring out a peace deal between the Israelis and Palestinians. It’s pretty picked over at this point. I’m not sure there’s going to be a creative technical solution which is going to get you there.

Jeff Alstott: I would say that there is a thing of staying within topics that have a bunch of attention on them but identifying those things where there’s actually a lot of agreement, but nobody is advancing the ball for reasons other than disagreement on the thing. For example, all of the policymakers’ attention is just on other stuff. It is all consumed with Israel and Palestine or Ukraine or what have you. They are simply attending to other things, and everyone would agree, “Yeah, we could do X,” if they merely had any brain power spent on it. But they don’t. That becomes your job — to move the ball forward on these things that have a fair amount of brain cells activated but still have a lot of buy-in.

Jordan Schneider: Even with Israel-Palestine, I’ve seen a really fascinating, well-done report about water sharing between the West Bank and Israel and Jordan. They just had a lot of hydrologists hang out with each other and come up with some agreement that seems reasonable. Maybe one day that will be a thing that will be useful to some folks. Even on the most emotionally charged, contentious topics, there’s always some room for thinking deeply that will be appreciated one day. We can all hope.

Anyway, Jeff, let’s break the news.

Jeff Alstott: The news is that I came to RAND nearly three years ago to create a thriving, vibrant ecosystem of policy and technology R&D on frontier AI issues and how they affect national security. My desire was always to make an ecosystem that would continue to function if I got hit by a bus.

Thanks to fantastic hires that we’ve made and various processes that we’ve created, that’s very much true. I don’t feel like I’m needed anymore for this ecosystem to continue to thrive and create the things that the US and the world needs. Within a few months, I’ll be stepping down as director of the TASP center.

Jordan Schneider: One other cool thing that RAND gets to do that CSIS or Brookings doesn’t is classified work. What’s exciting about that, Jeff?

Jeff Alstott: It’s great, and it’s one of the things that I consider a central institutional comparative advantage of RAND. RAND started as a defense contractor 70-odd years ago, and we’ve been doing classified work for the government ever since. It means that our work at TASP and elsewhere within RAND is able to move back and forth between the unclassified and classified barriers, which means we’re able to stress-test analyses in ways that can’t happen in the unclassified space. It means there are entire questions that we can seek to address that only live in the classified space.

But it’s also really critical for talent development. You mentioned that 24-year-old who is trying to break into the D.C. world. Well, them coming to RAND and doing the work and also getting a clearance will set them up better for whatever the next thing is — either another role within RAND or going to work at DoD or the intelligence community or what have you. Thankfully, we’ve got good processes for doing that classified work that I think are going to continue to be well-executed for the foreseeable future. I consider this one of the marked administrative institutional advantages of RAND, beyond all the obvious things like all the brilliant people you can talk about.

Jordan Schneider: What’s the shape of the questions that end up being done in a classified setting versus the papers that people read that TASP puts out?

Jeff Alstott: On some topics, there is intelligence collection. On some topics, there is intelligence collection that changes the conclusions. On some topics, there’s not intelligence collection that changes the conclusions. That in itself is interesting, and some audiences will care about that. If anyone wants to talk in a SCIF about which kinds of things change the sign versus not — happy to talk with them in a SCIF. We could do that someday.

Then there are also things. If you want to really do analysis on dynamic actions that the US could do, then those are things that you want to be doing in a SCIF. But as a concrete example that is not happening within TASP, literally next door in a secure facility, somebody is working on how the bombs and bullets of how a US-China conflict over Taiwan would go down.

There’s a pretty famous brief called the Overmatch Brief. We’ve had two versions of this. We’re on our third version now, which is just showing the net effect of all of Red and Blue’s capabilities being brought to bear in a Taiwan conflict. This is the briefing that goes to the White House when the White House asks, “All right, how would this happen?” It’s a classified analysis.

Jordan Schneider: We had Mick Ryan, a former Australian general, on. He recently wrote a book which is one of these near-future fiction novelizations of a US-China conflict. The way America wins in the end is they create a typhoon which they spoof out of existence from the Chinese weather buoy receivers, and then it hits the Chinese navy and they disappear. Blink twice if that is a thing that you guys have worked on at TASP.

Jeff Alstott: I’ve not worked on that at TASP.

Jordan Schneider: Good to know.

On AI Girlfriends and Politicians

Jordan Schneider: I want to give you some of my crazy AGI takes, Jeff because I don’t know who else I can do this with. My first one: we’re calling this the AI girlfriend net assessment. The thesis is that five to ten years from now, everyone is going to have an AI companion that they trust with their life. We already have the Swedish Prime Minister saying he consults ChatGPT all the time for work. You already have half of teens in America saying that they speak a few times a week with AI for emotional support.

I have an enormous degree of confidence that this is a one-way ratchet. As the technology gets better, we’re going to trust it with more and more facets of our life. From both a human intelligence perspective as well as a broader influence operations perspective, this seems like an absolutely enormous vector, both for the US to have a lot of fun with foreign leaders and populations’ AI companions abroad, as well as a vulnerability at home if someone can hack my AI companion or tweak the dials on a nation’s AI companion in order to get them to think one way or have civil unrest or vote differently.

The worries that we had with Facebook and algorithms or Twitter and TikTok and algorithms seem like child’s play compared to this threat vector that we’re going to have from having these Scarlett Johansson “Her” characters in our life that we have these strong emotional bonds with. Am I crazy?

Jeff Alstott: First, this is totally a thing that is happening. I know people of many different ages where they are increasingly incorporating LLM counselors into how they live life. I am not such a person — not yet. The thing’s not good enough for me.

Jordan Schneider: We’ll get you, Jeff. Don’t worry.

Jeff Alstott: There are several possible ways that this could play out. First, I would not be super confident that this is a one-way thing. Remember when cell phones came out and silencing your cell phones was an issue? You had to remind people at the beginning of events to silence their cell phones. Cell phones would go off all the time. People would have customized rings and there would be scandals about politicians having such and such ring tone. Now we don’t do any of that because society figured out you just have your phone on silent basically all the time. We figured out how to incorporate this technology into our lives.

Relatedly, kids and cell phones or any other devices — you’re a father, I am sure that you have had thoughts about when is the right time to give your child access to different kinds of technology. There definitely were eras where the parents hadn’t yet had time to think about it, so they were just doing stuff. Then we observed the stuff happening and then we said, “Oh wait, we need to change that.” It is not uncommon these days to see families who are just really intentional about “you’re not getting a phone until age X.”

There’s a Catholic University professor who’s now working at the State Department in the Policy Planning Office. His name is Jon Askonas and he wrote this great piece several years ago called “Why Conservatism Failed.” It’s basically identifying that within the right there is this implicit assumption that more tech of all kinds will always be good. We know this is false. We just talked about something like cell phones ringing or putting your phone in front of your infant’s face.

We have the opportunity to be intentional about how we incorporate these technologies into our lives. That includes as individuals, but also in the workplace and also as policymakers. You mentioned the Swedish Prime Minister. We’re going to get to the point where, yeah, maybe the Prime Minister has AI advisors, and the character of those AI advisors is highly inspected. We have a lot of thought about what is this AI? What is it trained to do? What are its supply chains? What is its ability to get manipulated? This is the kind of thing that we do for many areas of technology. As it gets to more critical use cases, we are more thoughtful about how we use it.

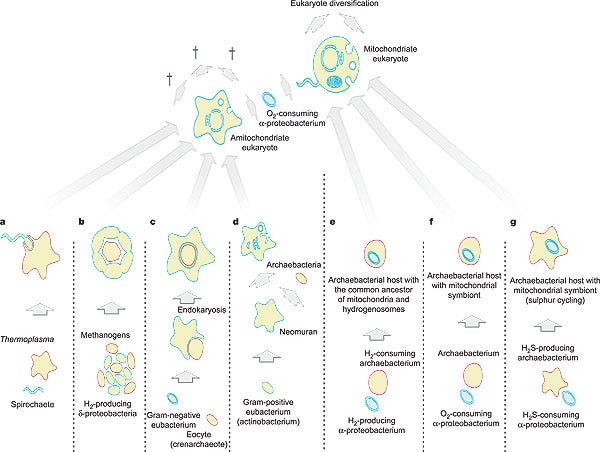

That is my claim about not assuming the ratchet. But there’s a whole other category here, and I think you would appreciate this: in all of our cells, all of our biological cells, there are these mitochondria. We all remember from school, “mitochondria — the powerhouse of the cell.” It helps you make lots of energy from respiration. What you may not recall is that there’s a fair amount of evidence that mitochondria were independently evolved organisms that we then evolved a symbiotic relationship with, where the mitochondria now live inside our cells and are reproduced as we reproduce. But they started out as a separate thing.

I think that it is totally possible that humans leveraging AI are going to end up in a cadence of life that looks a lot like the mitochondria with the cell, where indeed just what it means to be a human in an advanced technological society will be: “Of course you have your AI assistant, of course you have that,” just as “of course you have mitochondria in your cells.” The collective organism of yourself plus your technology assistance will be perceived as just as normal as the fact that you and I are both wearing glasses. Of course we wear glasses. What are you talking about?

The tech’s not there yet for me, but there will be segments of society where this is how they see themselves. I don’t have a strong bet on what timeline for that.

Jordan Schneider: The mitochondria version is the vision that — let’s give a 40% chance of happening, assuming the AI gets better and it gets smart enough that Jeff uses it more in his daily life. We haven’t even talked about how you want to automate all of your 50 TASP researchers. But the fact that that is even a thing you’re considering means that it’s going to be real.

There are a few things I want to pick up in your answer. First, it’s different from turning the cell phone ring on or having it not ring. It’s more like: we all have emotional needs and we all have jobs that change. The idea that you can be a journalist in 2025 and not be on Twitter is absurd because the world has changed. The metabolism of news is faster, and algorithmic feeds for a large percentage of humanity have outcompeted the needs for content that we had compared to going to Blockbuster and picking out a VCR from 100 videos.

It seems to me that it’s going to be really useful and powerful, and maybe we’ll get to something in 2050 where we have some good guardrails and all of our AI companions are localized and can’t be hacked by a foreign government. But we’re going to have some mess in the meantime.

Another piece of this mitochondria thing goes to my second AGI hot take: AI presidents and politicians. I think it’s probably going to first come with the CEOs, but then in the political sphere, where the ones who are using AI to augment and improve their analytical capabilities and are spinning up their own AI-powered task forces to give them the right answer to “Should I say this or that in my speech? Should I invest in that or this technology or open this or that factory?” will just have some evolutionary advantage where the people with the most money and power and influence in society are the ones that get more dependent faster on the AI.

Again, we’re assuming that AI is good enough to actually help you win that election or outcompete that company. But it seems to me like this is a very reasonable world that we could be living in 10, 20, 30 years from now where there is an evolutionary dynamic of: “Okay, if I’m the one who figures out how to work with my mitochondria best, then I can go pick more berries and have more children or whatever.” That’ll just happen for folks who learn to use leverage and ultimately just trust fall into letting the AI decide whatever they do — because humans suck and the AI is going to be really good.

Jeff Alstott: You’re speaking my language. A long time ago I was an evolutionary biologist, and I attend a lot to things outcompeting other things and the effects that has on the system. One of the ways in which this may shake out is that compared to a lot of other foreign policy and certainly national security people, I attend to hard power way more than I attend to soft power. I absolutely agree with your view of “dude, if you use the thing, you’re going to be better, so you’re going to win.”

Then it becomes a question of: “All right, but does it actually make you better?” As you mentioned, we’re wanting to automate a lot of tasks at RAND, and we could talk about that in more depth. But one very simple thing is using LLMs to auto-write things or to revise things. You work enough with LLMs, you probably can tell when the thing is written by an LLM. It’s using all the em dashes and everything. I have a colleague who just yells at everything made by LLMs, calling it “okay writing, but it’s not good writing.” And how much effort do we want to make it be good writing?

Merely having AI do all your things for you — as you say, a trust fall — is going to pay out in some domains and not others initially. Eventually it’ll pay out in all domains. I’m with you there. But there are going to be folks who are making trust falls too early in some domains that are going to get burned, and different people can have different bets on that one.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting because clearly we don’t even have to go to 2075 where AI is going to be good at everything. There are things that it is going to have a comparative advantage in over time. The types of decisions that a CEO or a general or a politician does is taking in information with their eyes and their ears and processing that and then spitting out, “Okay, I think we should do A. If I see X, then we should do B. If it doesn’t work, then maybe we should go to C.” That type of thinking seems very amenable to the analysis and thought that an AI could do over time.

We can make some nice arguments in favor of humanity that we have these lived-in-body experiences, and we feel history and context, and maybe we can read humans in a deeper, more thoughtful way if Jeff is deciding to assign this person versus that person. But we’ll have your glasses with a camera on them, and the AI soon will be able to pick up on all of the micro facial reactions that Jeff does when he assigns Lennart to do biotech instead of compute, and he shrugs a little bit but then says, “Okay, fine, whatever you say, Jeff.”

You can put the camera on Mark Zuckerberg and he has to make all these decisions — at some point in the next 30 years, a lot of the executive decision-making, it seems to me an AI is just going to be really, really good at. There are some really interesting implications.

What you were saying about some people are going to get burned: if that happens in the private sector and Satya adopts this slower than Zuckerberg and then Zuck wins out and gains market share, this is fine. It’s capitalism. Companies adopt technology in different ways.

But when you abstract it up a level to politics and geopolitics — “should we do a trade deal with this country? Should we sell these arms to this country? How should I phrase my communiqué in my next meeting with the Chinese leadership?” — that’ll be really interesting because we won’t have those case studies. My contention to you, Jeff, is we’ll get into a point where we will have had politicians who’ve tried it, although I think we are still going to have a president who is a human being for a while. Just because we have a Constitution that’s probably pretty Lindy, it’ll take a while for us to get rid of that.

But there’ll be some point in history where you get elected to governor, you do a better job running your state because you’re listening to the AI, and the governor in the state next to you isn’t. You’re doing a better job in the debate because the AI is telling you what to say and then you’re more pithy and sound sharper. We end up in a system that naturally selects towards the people with AI.

Maybe once we get that, we’ll also have the AI which is good and aligned enough to pursue things in the national and broader society interest. But maybe not. Perhaps even once we get there, we’ll still get burned because it’s not good at nuclear war or something. Sorry.

Jeff Alstott: Sorry, for what?

Jordan Schneider: Sorry to my audience. Are you guys cool with this? I don’t have a lot of guests I can go here with this stuff with, so we’re putting it all on Jeff.

Jeff Alstott: I really appreciate that you’re bringing up the audience right now because this very much gets to the earlier things we were talking about — the utility of analysis and the looking ahead. You are doing exactly the right thing, which is looking ahead to a place that most people are not looking ahead to or don’t want to go to. You’re trying to beat the market of ideas by being early. If you can do that well, that gives you time to have thought about the issues more, do more research and analysis, so that when this issue is no longer weird and enters the Overton window, then Jordan’s thought about it and Jordan’s there to be giving as good of informed analysis as possible. Not just Jordan, but Jordan’s audience.

There is this issue of how we select which unusual futures to lean into, especially when we have uncertainty about the future. You said some dates; I said some other dates. My median prediction for an AGI that can do every economically and militarily relevant task as well as a human is in the early 2040s.

But it’s totally reasonable to say that’s too far in the future. “I need to make bets on other nearer-term things that are still maybe eight years away so that I can be hitting those policy windows in eight years as they appear.” It’s worthwhile for there to be a portfolio either at the level of an individual or at the level of a center or a society in terms of we have some FTEs allocated to these different timelines and different scenarios.

The Utility of Expertise

Jordan Schneider: We’ve talked mostly about this in a technology context, but peering over the event horizon in a China context is also shockingly easy if you’re doing it — way easier than this AGI stuff. If you were someone who followed China at all, Bytedance was a company that you knew about in 2017 because it was the biggest app in China. If you followed China at all, you knew that they were building a lot of electric vehicles. You knew they were building a lot of solar panels.

This is the fun part of my little niche. Am I going to have a more informed opinion than you or Lennart about when AI is going to be able to make every militarily relevant decision? Not really. And by the way, that’s kind of an impossible question. But things about China are just happening today. Because of the language, because it’s halfway across the world, because the Chinese government is opaque (not really), but China’s confusing and hard and you need to put a little homework in before you understand what the deal is with some things.

It is so easy to tell people things that are going to wash up against their political event horizon activation energies over a six-month to two-year horizon. Which is why this niche is so fun, and you guys should come up with cool stuff and either work for Jeff or write for ChinaTalk. I’ll put the link in the show notes. We’re just pitching stuff here.

Jeff Alstott: I love how you describe this thing of “man, all you had to do was pay attention. It was easy.” The fact is, as we said earlier, people’s attention is on other things. All you had to do is be paying attention.

Just to get to the union of China issues and AI issues: DeepSeek. Many people who were paying attention were telling folks for many months before the DeepSeek models came out, “This team is awesome. We need to be recruiting them; we need to be doing everything we can to get them out of China and get them to the US or allies.” Now we can’t because their passports have been taken away.

Similarly, we knew the existence of a Chinese model of a certain level of capability at that time in history because the export controls hadn’t properly hit yet. They bought the stuff ahead of time. It’s because you were paying attention and then other people were not paying attention or were paying sufficiently little attention that their world model was sufficiently rough that they just didn’t know these things were going to be coming. This is the utility of well-placed expertise.

Jordan Schneider: It was very funny for the ChinaTalk team to live through the DeepSeek moment because we have been covering DeepSeek as a company and the Chinese AI ecosystem broadly ever since ChatGPT, basically. I’ve been screaming at people in Washington and in Silicon Valley, “These guys are really good. They can make models. You’re not smarter than them, I don’t think. Or they’re smart enough to fast-follow if you’re not going to give them enough credit.”

It wasn’t a hunch. The models were there. You could play with them and they were really good. It was remarkable to me to watch the world wake up to that. We gained a few extra points. I think we got 20,000 new free subscribers on the newsletter, which is cool. It probably helped us raise a little bit of philanthropic funding. There was some material and clout gain from being “right” or early to this.

But more what I have been reflecting on is: could I have screamed louder? Could I have screamed in a different color? What could I have done differently in terms of our coverage and writing and podcasting to get this message (which I had with 95% confidence) out to the world faster?

It’s funny because you can be right in some fields and very straightforwardly make money off of it. But being right in this field, you don’t want to be “I told you so,” and it’s an iterated game. It makes it easier next time. But I still reflect on that a lot about how my team and the ChinaTalk audience was aware of this company and the fact of the capability of Chinese model makers and AI researchers, and it still was a big shock to the broader ecosystem.

Jeff Alstott: Completely agreed. I love how you’re thinking about “what should I have done differently so that people acted.” This issue is relevant to the questions that you had at the top about the role of analysis or the effect of analysis. It is possible to do fantastic analysis that’s totally right and have no effect because you didn’t consider your audience.

There are definitely researchers in think tanks who write 300-page reports when what the policymaker needs is a page, and they get really detailed into their method when what they needed was the answer. They are speaking to an audience that turns out isn’t the audience that is actually at the levers of power.

There’s a variety of strategies of essentially how broad versus how targeted you are in disseminating your analysis. This can affect what analysis you choose to do and how to design it. That’s the thing that we focused on a lot at TASP and RAND.

Earlier you talked about the classified work. An advantage of that is that we’re able to engage with policymakers in ways that are difficult to otherwise. We’re running war games and tabletop exercises that may be unclassified or classified, and it enables you to engage with people otherwise. But it’s not just the classified work. Because RAND’s a defense contractor, we’re engaging with policymakers directly, frequently. It helps you build up a mental model of: “No, Bob sitting in that chair is the person who is going to make the decision. In order to inform Bob, I need to present the analysis in a way that is interpretable to Bob.” It’s not whoever my 10 million followers on X are; it’s Bob.

There’s this tension about where you place your bets along that Pareto frontier of being more targeted to certain audiences versus broader. Both are valuable, but it’s useful to have a portfolio approach again.

Jordan Schneider: I think you wouldn’t mind me claiming that I’m probably a third standard deviation policy communicator person in this little world and have learned a lot of the lessons that you have. I’ve built my career around a lot of the pitfalls that you’ve identified — not writing the 300-page thing — and somehow lived both on doing the original research and being the “popularizer” and writing in a way which is engaging and accessible and making the show hopefully fun as well as informative.

Maybe the answer is that I went too far in that direction and wasn’t hanging out with Bob. Maybe Bob isn’t someone in the Defense Department. Maybe Bob is a New York Times reporter or a Senate staffer. Actually, it’s probably not a Senate staffer. Let’s talk more about Bob because in the DeepSeek case, he wouldn’t be Marc Andreessen, right? Bob wasn’t anyone in the AI labs — they were all aware of this as well. Maybe there was just enough money on the other side of this discussion that it was too inconvenient a fact to internalize. What do you think?

Jeff Alstott: Who Bob is depends upon what exact policy move is relevant here. You just mentioned both people in government and people out of government. The frontier AI companies — probably any one of them could have, with sufficient will, tried to go headhunt every member of the DeepSeek team. They had the legal authority to do this and possibly enough cash, whereas government would have different abilities but not, ironically, a ready-made answer for just “hey, we’re going to come employ you.” The US government does not currently have anything like an Operation Paperclip, as was done with German scientists after World War II. The fact that it doesn’t have such a thing means that its moves available to it for handling a DeepSeek crew is more limited.

Who Bob is depends upon the exact policy move that you want. For what it’s worth, you made the suggestion that maybe you’ve gone too far in one direction; I’ve gone too far in the other direction, which is part of why we like each other — because we’re both doing these complementary things where I’m not on X, I have no social media presence, I’m from the intelligence community. My job is knowing the middle name of the relevant staffer because that allows you to infer what their email address is because the middle initial is in there, and who reports to whom and the palace intrigue and that kind of thing. It’s useful for what it is, but it’s only one kind of usefulness.

Another shout-out for anybody who’s looking to apply to TASP: our conversations and impact are much broader than the public publications that we have on our website because of this bias that I have had. But maybe it’s the case that we ought to be leaning into publishing more than we have been.

Jordan Schneider: All right, I want to close on the vision for automating this. We’ve talked about automating AI presidents, but what’s next?

Jeff Alstott: Right now at TASP and within RAND, we’re working to find ways to use the latest AI technology to automate steps in our research processes to achieve greater speed and scale. There are at least two ways to approach this: automating research management and automating research execution.

Research management involves office processes: ensuring documents go to the right person, checking that documents follow proper structures and templates, routing them to publications with the correct billing codes, and other administrative tasks. Much of this automation doesn’t require AI and can use standard tools, though adding LLMs enables us to plug key steps where human intervention is no longer needed. This allows processes to go from almost fully automated to completely automated, which is excellent. We’re continuing to build this out.

The more interesting aspect for your audience is research execution: figuring out facts about the external world and what they mean for policy options, what we call analysis. We’re currently exploring two areas, both leveraging the fact that while LLMs can be weak in their world modeling and the context they bring to problems, when provided with proper context, they can automate and iterate effectively.

First is quality assurance. We have an LLM review documents to identify problems: Is any of this incorrect? Is the math wrong? Are the numbers accurate? Does this reference match that reference? When a claim cites a particular source, we have the AI read the citation to verify whether the claim is actually supported. With 100 citations, you can process them quickly. We’re working to speed up our QA processes. This won’t be perfect with today’s technology, but it will help significantly.

The second area is what we call a “living analysis document.” Once humans have completed their analysis, written it up, and made critical high-context decisions about how to structure the analysis — what data to use, how to set up the model, what the actual issues are and how they interplay — once humans have done all that and produced the paper, can we have an AI repeat the analysis a year later with the latest data automatically? This automatic extension and continuation of analysis seems like potentially low-hanging fruit that’s doable, at least partially, with today’s technologies.

I’m hoping this will enable us to do not just more analysis in areas where we currently work, but by freeing up human labor, we’ll be able to embark on new analyses in new areas, expanding where we focus our attention.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s close with some reading homework. Give the people something substantial.

Jeff Alstott: I just watched K-Pop Demon Hunters last night. It was awesome. I have a rule: no work or high cognitive effort activities after 8 PM. There are people like yourself who read dense books late into the evening, but that’s just not me. It’s K-Pop Demon Hunters for me.

All right, let me think of something substantive that folks might want.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, last night I was reading Stormtroop Tactics — thank you, Mick Ryan, for taking over my brain. It’s about the evolution of German infiltration operations from 1914 to 1918. It’s pretty well written. What’s cute is that the dad wrote it and dedicated it to his son, who was a colonel at the time. He was like, “I wrote you this book so you can learn about tactics better.”

Jeff Alstott: My recommendation is “The Extended Mind” by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. There may be just an article, but there’s also a book on the extended mind by Andy Clark. This is a classic cognitive science piece.

Because I’m a cognitive scientist, which was my original training, I assert that if you’re thinking about AI futures, what’s happening with the human condition and AI, and what’s possible, much of the older cognitive science work will be more helpful for making accurate predictions and bets than the particulars of machine learning today. The machine learning particulars may matter too, but if you’re looking more than five years out, certainly more than ten years in the future, you shouldn’t focus on LLMs specifically, but rather on more fundamental cognitive science concepts.

The concept of the extended mind, which people were thinking about decades ago in cognitive science, relates directly to the issues you brought up about AI companions. It’s essentially about how we think about what our mind is, where it lives, and where it’s physically instantiated. This includes obvious things like notes. You write down notes and they become part of your mind. Your brain remembers pointers to the notes, but not the contents themselves. There are definitely people who are diminished when they don’t have their notes available. Books, AIs, and other tools are all part of your extended mind system.

If you want to think about how different AI futures could work, cognitive science in general, and if you care about the AI companions issue for presidents or otherwise, then “The Extended Mind” in particular is essential reading.

Jordan Schneider: That’s a beautiful thought. I’ve done a lot of self-promotion on this episode, but we’ll close with it being an honor and a pleasure to be part of this audience’s collective mind. Thank you for your time and for trusting the show, the team, and my guests to create content that stretches your extended mind in interesting and useful ways. Thanks so much for being part of ChinaTalk, Jeff.