How the US Won Back Chip Manufacturing

State capacity from scratch

We’re here for a CHIPS Act megapod, in person with Mike Schmidt and Todd Fisher, the director and founding CIO of the CHIPS Program Office, respectively.

We discuss…

The mechanisms behind the success of the CHIPS Act,

What CHIPS can teach us about other industrial policy challenges, like APIs and rare earths,

What it takes to build a successful industrial policy implementation team,

How the fear of “another Solyndra” is holding back US industrial policy,

Chris Miller’s recent interest in revitalizing America’s chemical industry.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app.

This post is a collaboration with the Factory Settings Substack. Subscribe for more insights from former CHIPS Program Office leaders!

Was the Fab Boom Inevitable?

Jordan Schneider: We’re about a year out now. There was a long arc of Congress and two administrations imagining what the CHIPS Act could be, and now we’re sitting here in the first quarter of 2026 with fabs popping up everywhere — the biggest semiconductor buildout in memory. Everyone in the world wants more chips and more manufacturing capacity, and a decent percentage of that is now coming online in the US. That wasn’t necessarily baked in. Looking back, how do you give credit to the incentives versus the macro trends that would have led to some version of this buildout regardless?

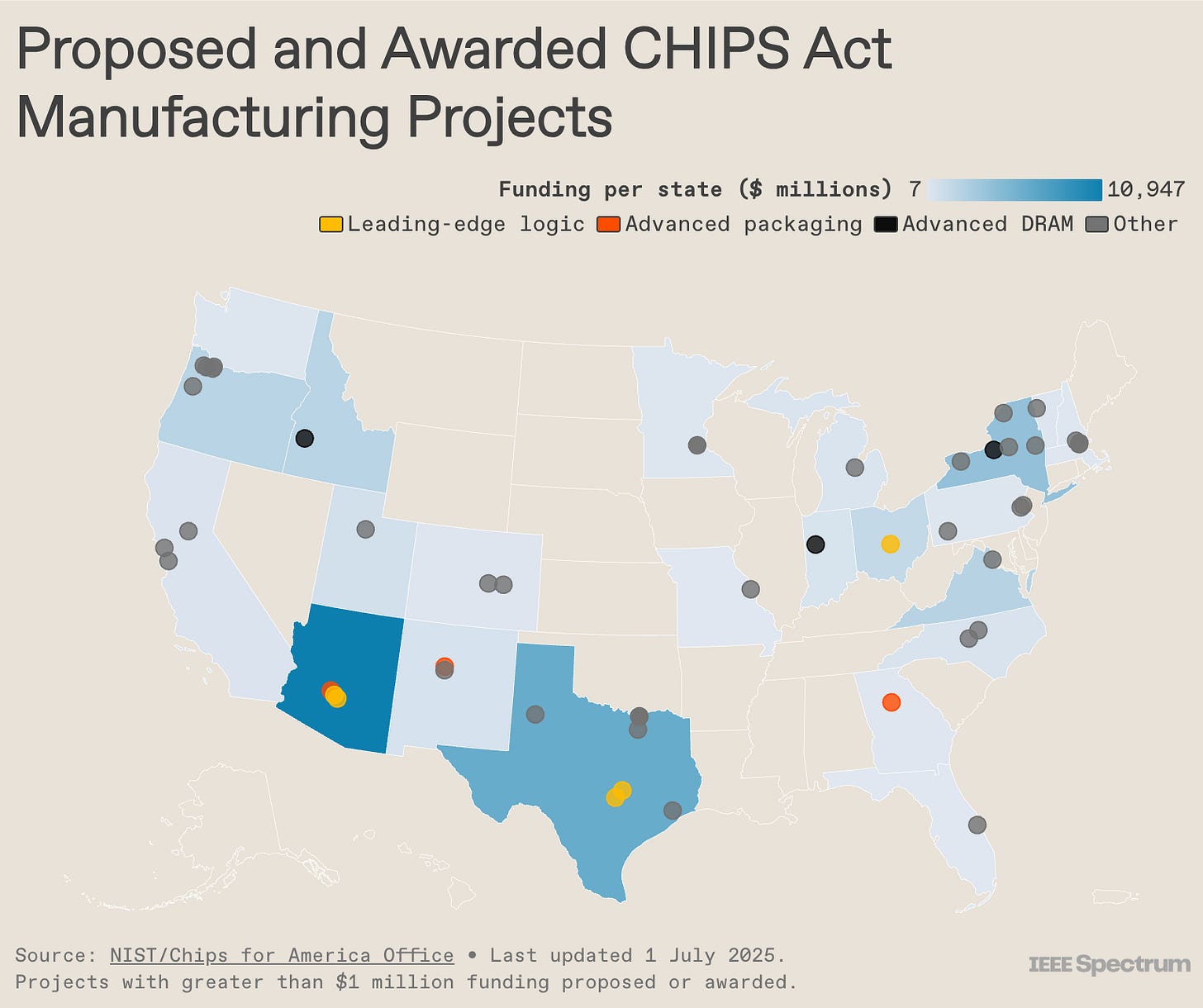

Todd Fisher: It was definitely not baked in. If you go back to when the CHIPS Act passed in August 2022, ChatGPT hadn’t even launched until November of that year. The concept that AI would drive this massive demand cycle was not part of the original calculus — that became clearer as the years went on. At the time, we were projecting a trillion-dollar semiconductor industry perhaps by 2030. Now, that trillion-dollar milestone is going to be hit this year. The demand cycle was not anticipated.

What we did accomplish is acceleration. It’s hard to shift an entire business from outside the US into the US along with all of its supply chains. That takes time, effort, talent development, and construction. The building that’s happened — what we incentivized — has enabled a more rapid participation across the industry.

Mike Schmidt: A massive buildout of fab capacity to meet the moment on AI around the world was inevitable once the AI boom really took off. CHIPS was ultimately about where those fabs would get built and whether we could get a good chunk of them here. The CHIPS Act played a huge role in that.

A few factors stand out. The investment tax credit was enormously important — a 25% cost offset on investment that provided a strong baseline subsidy. Our office managed $39 billion in grants, and we mobilized around that. That worked together with some natural advantages we have as a country: a strong economy, a strong workforce, and — really importantly — the major customers of semiconductors are American companies. When companies look around the world, it makes sense to be close to their customers. A confluence of factors — some market-driven, some about public policy, some about execution — all conspired to put us in the position we’re in.

Jordan Schneider: Taking a step back from CHIPS, when you think about the playbook you ran to promote domestic manufacturing or shape the market, what’s the holistic framework? What aspects of CHIPS worked for and against you as you were trying to put government money behind an industrial aim?

Todd Fisher: Everything’s a trade-off. If you’re going to put — adding the ITC and our subsidies — $100 billion into the semiconductor industry, that’s $100 billion you’re not putting somewhere else. You have to frame it that way: we can’t do everything, so we have to be focused.

I laid out this approach in one of our Substack posts on Factory Settings. Something has to be critical — critical for national defense, for people’s health, for enabling technologies of the future. It also has to be compromised in a way that’s going to cause us pain. We’re seeing that right now with the weaponization of economic tools around rare earths, semiconductors, and other specific choke points that are genuinely negative from a national and economic security perspective. And you have to determine that your effort — your subsidization, your tax incentives — can actually make a difference. That gets to the nature and structure of the industry, the supply-demand dynamics, and the cost factors, and whether a subsidy over some period of time can shift the fundamental economics.

Those conditions won’t be true across the board for all industries, so you need to evaluate all of them when designing industrial policy.

For chips, it’s clearly critical — they’re an enabling technology for just about everything happening right now. You can look at the newspaper articles every day about memory shortages and the need for TSMC to make more chips. That is going to be the ultimate chokehold on AI. It’s clearly compromised, because up until a couple of years ago, we had zero percent of leading-edge logic or memory being produced in this country. Now, for the first time in over a decade, we do. And in our view, it’s changeable, because the semiconductor industry is not labor-intensive — it’s highly automated. The cost differentials are much more focused on front-end construction than back-end operations. If you can correct the cost differentials on the front end, there’s a path to sustainability over time. Those are the aspects that made sense for leading-edge semiconductors specifically, and that framework can be applied elsewhere.

Mike Schmidt: The big analytical project of the moment is figuring out which industries have a similarly strong and compelling national security case for intervention. Once you decide intervention is necessary, our experience with CHIPS suggests pretty strongly that you have to study that industry closely to understand the tools and approaches that will work — whether that means onshoring, working with allies and partners, or otherwise creating a more resilient supply chain.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the sequencing. We have this bill, and in it there’s a little bit for advanced packaging, some money for R&D, but it’s basically telling the executive branch, “Figure it out. We think this is important and we came to a number. You go from there.” That seems like the wrong sequencing to me — I don’t know.

Mike Schmidt: You need a mix of purpose, direction, and discretion. There were two sides of CHIPS — $11 billion for R&D and $39 billion for manufacturing incentives. Our part was the $39 billion for manufacturing.

Jordan Schneider: Right, we don’t talk about that other $11 billion.

Mike Schmidt: For us, it was basically a blank slate. There was one $2 billion carve-out for fairly mature technologies, but we wanted to spend more than $2 billion on that anyway, so it wasn’t a binding constraint — it was a floor rather than a ceiling. That put us in a position of asking, “What do we want to achieve with these funds, and what do we think we can achieve?”

Early on in program implementation, when you’re just building a team and racing against the clock to get your funding announcement out the door so you can take in applications, there’s a baked-in narrative that things are moving too slowly. It took a fair amount of discipline for us to say in those early days that we needed to invest the time and resources to really articulate a vision.

We ended up doing that through a document we called our Vision for Success — Dan Kim was on a couple of weeks ago and talked about it as well. That was our stake in the ground. We had a lot of discretion, and we wanted to hold ourselves accountable. We did a whole bunch of work to figure out what our objectives would be, and that document ended up being a really important disciplining mechanism — not just externally but internally — because it created the framework by which we would measure our own success.

Todd Fisher: You said you’re not sure it was the right sequencing. I actually think it was. Identifying the big issue that could potentially move the needle for the country — semiconductors broadly — and then enabling the people who would actually execute and implement the program to dig in with the right expertise and think through different approaches: that’s the right way to do it.

If you legislate something with too much detail, you’re going to miss the nuances of execution and implementation that are so important. The effort we put into the Vision for Success, the way we thought through program design and incentives, the kinds of companies we wanted to approach, who we wanted to draw in, how we set up the whole process — we were quite lucky to have the flexibility to design it from the ground up.

Mike Schmidt: That said, you can go too far in the direction of discretion. For us, we knew it was chips. You could imagine a world in which, given all of these vulnerabilities and choke points, you take a huge pot of money and just give it to the executive branch with the instruction to advance economic and national security. There are benefits to that — you can imagine a robust, flexible executive making dynamic decisions, addressing problems as they emerge, and moving quickly.

But with CHIPS, we had a huge benefit from the fact that we had a bipartisan law with a clear overarching objective, and we could then define the specifics within that. It allowed us to build a team centered on that objective, develop deep expertise in the industry we were focused on, and build internal know-how. In the broader political context, it also gave us a clear measuring stick that we’d be held against.

Jordan Schneider: The backdrop of what I was getting at is that the origins and legislation around the CHIPS Act were this random confluence of an intellectual effort plus COVID, and it happened to be the right moment with enough momentum behind it. If you ran 2018 through 2022 thirty times, the CHIPS Act probably happens maybe two or three times. But the question is, what if you had $85 billion to do American economic security broadly? Would we be more economically secure today if that had been the mandate, as opposed to directing all the money specifically toward chips?

Mike Schmidt: Personally, there’s a lot of value in Congress identifying key target areas and then telling the executive branch it has broad discretion to figure out the how. You can spin a lot of wheels trying to identify targets from scratch.

Jordan Schneider: The IRA is a counterexample, right?

Mike Schmidt: The IRA, unlike CHIPS, isn’t one pot of money or a single tax credit doing one thing. It’s an assortment of different tax credits and programs, each with a different objective. A challenge with the IRA is that some of those objectives are targeted at different things, and how they all work together into a coherent strategy is tougher than when you have one specific goal and a few tools to mobilize toward it.

Todd Fisher: But why do you say the IRA is a counterexample?

Jordan Schneider: Maybe it’s not. The real counterexample is that no one would ever get $100 billion to do economic security in the abstract. The happy medium — where the executive branch has enough trust from Congress to actually do things that don’t get earmarked away into, I wouldn’t say oblivion, but not the strategic version of the thing — probably requires Congress signing off on a particular industry.

Todd Fisher: I probably haven’t thought enough about this, but the CHIPS Act for an industry that’s going to be a trillion-dollar market was very appropriate. Take rare earths and critical minerals today. It’s hard to just wait for Congress to figure out this is an issue and pass legislation. There’s some combination needed. The right answer isn’t “here’s $100 billion, figure out what to do with it.” It’s more like: chips are important, we’re going to do something very focused there, and here’s $10 billion to address things that are going to become critical.

Consider the rare earth industry. These are 17 different elements, and the overall market is about $5 to $6 billion. You can solve the rare earth issue because it’s a $5 to $6 billion problem. You can’t solve a trillion-dollar industry the same way. There’s a different mindset required. You could look at APIs, pharmaceuticals — there are different choke points across the system that we need to be more nimble about addressing. Then there are the big things that take massive amounts of time, effort, and money.

Jordan Schneider: The takeaway is that there are two buckets — giant industries where the amount of money needed requires direct congressional appropriation, and then a second category where it would be nice to have an office that looks at these issues with a smaller pot of money and the ability to issue debt or whatever other tools — things that are an order of magnitude smaller where we don’t have to stress as much.

Mike Schmidt: That’s a good idea. I like it.

Jordan Schneider: I stole it from you.

Mike Schmidt: There’s also a question of what kind of state capacity you need to develop. For something like pharmaceutical APIs, it might make sense to have a dedicated program because it’s such a specialized market requiring deep technical expertise. Whereas something like critical minerals might be more straightforward in terms of what you’re trying to achieve and how the industry is structured.

Jordan Schneider: When it comes to this idea of discretion and Congress trusting you, we’re in a different world today. I remember you being very focused on transparency — wanting to make the process fair and making sure everyone felt they were getting a fair shake. Now we’re living in a world where relatives of presidents and cabinet members sit on boards of companies receiving government money.

It feels almost quaint in retrospect how focused you were on that. But my worry with the smaller, more nimble and discretionary efforts is that we’re going to enter a backlash to the current moment where there just won’t be any appetite or trust for this kind of thing.

Todd Fisher: That all comes down to governance and how you set things up — specifically, the ability to insulate the process from politics and preferences that intervene in unconstructive ways. The good news about CHIPS is that it was set up in a way that our team felt pretty protected from politics. That was partly structural, partly how Gina Raimondo approached it, and partly about personnel. Neither of us were political appointees. Many of the people I hired on my team were Republicans. It depends on how you set these things up — whether it’s purely transactional wheeling and dealing, which is one approach, or whether you build something more institutional. You could set something up along the lines of the DFC, where it’s insulated and more trustworthy, with built-in transparency. You’re right that there might be a backlash, but I would caution against retreating from this, because we’ll miss something really important if we do.

Jordan Schneider: Could you do the short version of that, Mike?

Mike Schmidt: On balance, I would urge simple tax credits and other straightforward tools as the default. There’s probably an additional bar you have to clear before deciding when the discretionary approach makes sense, because the potential for politicization and abuse is real.

For us, the semiconductor industry was such a distinctive case. The scale was dramatic, the industry was highly concentrated, and creating a hub in the government that engaged dynamically with the industry to form partnerships, scale up investment, and make specific commitments we felt were important for national security — all of that proved really valuable.

There are other circumstances where discretion can be helpful. On rare earths, discretion right now is probably useful just because it’s such an emergency that it doesn’t make sense to throw a tax credit out there and see what happens. But that’s partly because our own policies created the emergency. A longer-term, more stable industrial strategy would identify a set of priorities, establish a baseline of market-based incentives and tax credits, and then layer in discretion for the key areas where it really makes sense.

Todd Fisher: I broadly agree, but the challenge is that tax credits only go so far — they’re really just one tool. When you start thinking about rare earths, some of the things the Trump administration has done are very credible, particularly on the demand side of the equation, providing price floors and a certain amount of guaranteed demand.

We didn’t have that. One thing we really lacked in the CHIPS Act was any kind of demand incentive. We were forced to rely entirely on the bully pulpit — engaging with Apple, Nvidia, AMD, Broadcom, and others, telling them this was in their interest and that they needed to be helping us so we could help them drive supply development. Aggressive supply expansion only happens with real demand signals. Those exist today, but they didn’t four years ago.

I prefer the tax credit any day, but it’s a very evenly spread incentive, and you miss a lot. You miss a number of tools, and you miss the ability — which we really took to another level — to push companies to do more. With a tax credit, companies are going to do what they’re going to do. With our discretionary money, we were able to say: no, we need you to build another fab. We need you to bring this technology here. We need you to shift your inventory levels. That allowed us to be much more proactive about our priorities — like drawing advanced packaging facilities to the US, which wasn’t on the table for the first year or so.

Mike Schmidt: The other thing, from an institutional standpoint: Treasury’s Office of Tax Policy is a fantastic institution within the government. I worked very closely with them in my role before CHIPS. But they’re never going to be the hub of energy in government to make an industry succeed — that’s not their role. They write regulations to make sure congressional objectives are being met, that credits aren’t ripe for abuse, that there aren’t loopholes. That’s not what we did. What we did was build a group of people — 180 at its peak — who woke up every day and thought: how can we make the semiconductor industry successful in the United States, and what tools do we have at our disposal to do that?

Jordan Schneider: There’s so much to pick up on. I’m very thankful that your child was two years old and not a 25-year-old hotshot semiconductor hedge fund member.

The institutional question is a really interesting one, though. You alluded to the DFC. The Fed is another example — though I guess we’re politicizing that one too now. But the idea that you could have some chunk of the government whose job it is to prevent China from having economic leverage over the US, or to do everything possible to minimize that — with a dedicated pot of money and tools over a sustained period — seems like a bipartisan thing.

Mike Schmidt: There’s a lot to disentangle in that. Having some chunk of the government that focuses on this is really important. Even the Trump administration ended up taking on the CHIPS office and putting it inside what they called the United States Investment Accelerator. There is this notion that what we built could be the foundation for something more durable — not just about semiconductors, but broader. A permanent institution that pulls people from the private sector and public sector to focus on this set of problems, one that develops methodologies, rigor, and expertise around it, would be hugely valuable.

Jordan Schneider: We have the U.S. Digital Service with these little rotational programs for software engineers. Why not industry analysts?

Mike Schmidt: It seems like a natural fit. And it doesn’t have to be rotational — it could just be that they’re in charge of allocating whatever pool of money exists. There are two downstream questions worth pulling apart, though. One is how much discretion this office has over what industries receive funding. Does Congress set the objectives and identify the priority industries, then hand it off to the office? Or does the office have more discretion? The second question is about independence from political interference and finding the right balance. We created systems and structures within our operation to keep politics out of it to the extent we could, but that wasn’t legislated. It was about establishing processes and norms. There’s a whole set of questions around how to formalize that.

Todd Fisher: I go back and forth on this. The special nature of what we had was the ability to attract the talent we attracted. Most of those people have now left — not only because the administration shifted, but because most of them weren’t necessarily partisan people.

Jordan Schneider: They couldn’t do math fast enough?

Todd Fisher: No, but obviously they should have had better talent. Come on.

They came from the private sector and wanted to go back to the private sector. The rotational aspect you mentioned would be great. But the thing that makes me nervous about setting up a separate institution — and on balance, I do think it would be beneficial — is how you sustain a pipeline of really talented private-sector people. Not only financial and investment types, but semiconductor and industry experts. How do you bring them in dynamically, in a way where people want to be there and feel that the experience furthers their career rather than setting them back?

There aren’t many examples in government that pull this off. The Fed is a good one, but it’s very difficult to set up another Fed. That’s going to be really hard. Then you say, well, maybe the right answer is that when you have something big, you just do it again and figure it out. I’d love for there to be a centralized function, but I have doubts about whether it would be excellent or merely good.

Mike Schmidt: The counter to that — and my sense is that, yes, a lot of people we worked with left, but they’re hiring people now, and many of them are pretty good. The counter is that this set of issues is going to be at the forefront of national security and competition with China for the foreseeable future. That naturally draws people. People came to us not just because they thought we were awesome or because they loved Gina Raimondo — though that was part of it. A big part of it was simply that people want to serve. That piece will continue.

Having served around ten years in government, there’s this enduring mystery — why do certain agencies thrive and maintain an awesome culture over time, while others just atrophy?

Todd Fisher: The other thing is the fragmentation. One of the things that would be great to fix is how many different entities are involved. Even for us, we had to deal with Treasury on the tax side, and even within Commerce, export controls were separate. Then when you start talking about demand and scale, you’ve got the DOD, the Department of Energy — and even at the White House level, how do you create something that integrates all of this?

Some countries have models worth studying. Japan, for instance, has a structure more focused purely on economic security that combines all these functions and breaks down those barriers. It would be really valuable to have some of those barriers eliminated and bring together cross-functional disciplines.

Jordan Schneider: There are two pieces of this. One is mapping out the Chinese economic escalation ladder — the universe of disruptions that could devastate the American economy. Map all of that out. Develop playbooks with dollar amounts, GDP estimates, and labor projections for every contingency we could face over the next five to ten years. Then you can present the executive branch or Congress with a well-thought-out menu: here are the problems, here’s what it would cost to fix them, here are the five tools available. And this analysis is independent — not coming from the chemicals industry, a rare earth miner, or a semiconductor manufacturing firm, but from something that’s working on behalf of the American people.

The question is whether that analytical work alone is exciting enough to attract the best and the brightest, or whether you also need the ability to say, “We’re solving this, and we have real money to deploy.”

Mike Schmidt: You need the money side for the best and brightest.

Todd Fisher: One hundred percent.

Mike Schmidt: The analytical side already exists to some degree — ITA at Commerce has a lot of that capability and a lot of great people.

Jordan Schneider: But they had two people on it.

Mike Schmidt: Right. You could definitely imagine a more robust version of that. But to truly attract a broad range of people who want to make a difference, you need more than just analysis.

Jordan Schneider: People actually want to do something.

Mike Schmidt: Exactly. Telling someone, “Come up with a plan that Congress may or may not enact” — in an era when Congress doesn’t seem to do very much — it’s hard to see that being enough. One of the most humbling experiences of doing CHIPS was the commitment to the mission. People would come in and just work their asses off. They stayed longer than they planned. They really wanted to get the job done and felt it was important. A lot of people stayed well into the Trump administration because they were focused on what mattered. That’s always awesome — truly cool to see. But people show up when there’s really something to do.

Jordan Schneider: Right, but that’s the argument for having a small sovereign wealth fund-type entity where you can pitch to an investment committee or something.

Todd Fisher: You have to have capital.

Mike Schmidt: If money is there but the question is how it’s going to be deployed, that’s a big job — a very different thing. You need the money to build state capacity. It falls to those of us outside of government to figure out the right framework for Congress to act on in a bipartisan way.

Todd Fisher: Don’t call it a sovereign wealth fund. A sovereign wealth fund, in my mind, takes surpluses that a country has and invests them to enhance returns for the government. This is more of an investment entity — I don’t know what the right term would be — where you’re actually trying to influence industries in a more targeted way.

The concept is great. What I struggle with most — and Mike as well — is that what we did over those two and a half years is hard to look back on and say, “That’s repeatable.” It’s not easy to replicate. You can’t just hand someone a playbook and say, “Go execute.” It feels like a one-off. And I believe strongly that for us as a country to be successful long-term, it can’t be a one-off — it has to be repeatable. I want to really believe we can create a separate entity that attracts the best and the brightest so we can do it again. That’s something I struggle with a lot.

Jordan Schneider: This is why I want to come back to the corruption piece. Part of what made this a one-off was that the team was above reproach. The pressures you faced were none of the really ugly ones we’ve seen throughout American history when the government spends lots of money. What worries me is that what we’ve seen over the past year — and will continue to see over the next three years — is going to poison the well for this kind of work. Work that all of us agree needs to happen. People just won’t trust it.

Mike Schmidt: There are many respects in which what’s happening in the world right now is going to make this kind of work harder going forward, and that’s certainly one of them. If you begin to question the integrity of these efforts, it makes it harder to sustain the political will — or you end up choosing different tools, like tax credits. That’s a big piece of it.

But there are others. The whole discussion about allies — we spoke throughout the Biden administration about the importance of working in concert with allies and partners. There’s a moment right now, in the wake of Carney’s speech and this broader reckoning with what’s happening with our traditional allies and partners, where thinking through new frameworks to create durable strategic economic connectivity is really important. There’s probably a longer list than that, but it’s a critical issue to raise.

Jordan Schneider: It’s frustrating to watch the critical minerals work, because clearly there are really good people doing really smart things — that’s ninety percent of it. Then you get a story or two and you think, “What the hell?” Stopping a negative outcome isn’t going to resonate with the American people. Having a critical minerals reserve isn’t going to get headlines or clicks. What gets attention is someone controversial ending up on a board.

Mike Schmidt: But there’s a more hopeful flip side. The folks doing this work now, in the trenches figuring out which tools to apply to which situations, running into the same state capacity constraints — or maybe blowing through them in ways we didn’t — over time, they could develop into a group of capable technocrats who inform this work constructively going forward.

Todd Fisher: I’m actually more positive on the critical minerals and rare earths front. There are multiple things happening. Getting stuff done in government is hard, for all the reasons we just discussed. But being able to break through logjams, push things forward, and deploy multiple tools — that’s what’s happening in the rare earths space. Multiple efforts are underway, multiple tools are being employed across the board. I may not agree with all of them, but broadly speaking, deploying those tools aggressively, building a strategic reserve, and bringing countries together to think through the issue collectively — those things fit together. You’re right that one negative can erase all that good work.

But hopefully this is a sample of what you might be able to do with a smaller industry, because it’s a solvable problem. It takes time, but it’s totally solvable in dollar terms — even if we had to subsidize it forever, given the scale involved. That would not be true of many other areas where there are real choke points.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about doing things that lawyers get upset about. Mike, how hemmed in did you feel? If you knew then what you know now about how far an administration could push things without major blowback, what would you have done differently?

Mike Schmidt: We tried to do as good a job as we could thinking about risk holistically, and that’s true at multiple levels. With individual deals — Intel is a risky deal, but there’s a lot of risk in not doing a deal with Intel, given the critical role they play in the broader ecosystem. But it’s also true when it comes to questions of process.

One of the things I used to always tell the team as we were thinking through how to get something done: the biggest risk of this whole thing is that we don’t get it done. We’re going to run out of clock, we won’t have gotten our deals across the finish line, and the country will be worse off for it. We needed to think flexibly and dynamically about all of this. We did a pretty good job of that, but looking back, there are areas where it’s really worth asking: could we have been more willing to take risks? Could we have prioritized efficiency over some of the risk avoidance?

Todd Fisher: Where would you have taken more risk?

Mike Schmidt: We have a new Substack where we’re talking about some of this. We discussed how hard it was to get our deals done. For listeners, we would reach term sheets with our applicants laying out the basic economic terms — how much money, over what milestones, and so on. Then we had to turn those term sheets into final award documentation, which meant diving into a bunch of nitty-gritty legal details.

Each individual issue involved a real trade-off, and you could understand why the government cared about it. If the government gets sued because of something the company did, should the government be protected? If the company tries to sell a project or sell itself, should the government have the ability to reassess the deal? If the company breaks the law, violates export controls, violates sanctions — all of these provisions accumulate to create a huge amount of friction in getting deals done.

We thought about each one rigorously and made a lot of trade-offs along the way. It’s not as though we weren’t trying to be flexible. But when you talk about sustainability, I look at that and say I would definitely advise a team going in to do this again to put all of that on a list and just decide up front: we don’t care about all of these. Cut twenty-five or fifty percent of them. That means accepting more structural risk in the deals, but it makes the whole process much more manageable and dollar-efficient.

Todd Fisher: I agree with that. What keeps coming to mind for me is the demand side of the equation — how we could have pushed Nvidia, AMD, Apple, Broadcom, Qualcomm, and others harder to help accelerate things and set up an environment that moved faster, particularly with some of TSMC’s competitors. Whether we could have done more, I’m not sure, because we didn’t have the actual tools. It was mostly the bully pulpit.

Jordan Schneider: Was there ever a thought to go back to Congress on that side?

Todd Fisher: I don’t recall. Getting new appropriations for demand incentives — particularly giving money to some of the largest trillion-dollar companies in the world — is a difficult ask. We structured some things where we agreed to pay for porting costs to incentivize companies to dual-source or shift some of their work from TSMC to Intel or elsewhere. But it was all cajoling. Could we have pushed harder? I don’t know. We didn’t have the tools, so it was just persuasion.

This administration is bringing every tool to bear in a very transactional way — “if you don’t do this, I won’t do that.” That wouldn’t have been an approach we’d have been comfortable with. But between where we were and where things are now, there’s probably quite a bit of space in between.

Jordan Schneider: Instead of asking for daycare, threatening to get CEOs fired would have been an interesting approach.

Mike Schmidt: It is a question of norms — how you interact and interface with industry. It would have been tempting. I remember at one point we had a conversation about a company we were dealing with that we knew had something going on with BIS. You could cross those two things pretty easily and make it much simpler to extract the investment you were looking for. But there was just this sense — I believe it was Leslie, our general counsel, who said, “We don’t do that.” And the rest of us were sitting there thinking, “That seems right.” Because once you start going down the path of the government exercising its power in one area to get what it wants in another...

Jordan Schneider: Then you get donations for the East Wing. That’s how it all comes together, right?

Mike Schmidt: Right. That felt like a line. But at the same time, maybe we were a little too precious about it. That’s an interesting question in terms of finding the right balance, because at the end of the day, you’re trying to get these companies to do things that are important for national security.

Todd Fisher: That’s the one area where people might push back. You could say we should have tried to get TSMC to build more fabs, but to me that’s a total red herring. On TSMC, our major effort was to get them to build three fabs. Why three? Because of the way they construct their fabs, once you build the third, it’s almost guaranteed they’re going to build a fourth. Once you have four fabs, you’re going to build six because you want that mega-fab scale. Our view was that we didn’t want to spend the extra money to get another fab up front. If we could get them to three, the rest would take care of itself.

The fact that they’re now saying they’re doing more — because demand projections moved from a trillion dollars in 2030 to a trillion dollars in 2026 — doesn’t really mean anything to me. It’s not as though I anticipated that acceleration. The other question you could ask is whether we could have pushed these companies harder to do more. We pushed them really hard, and we got them to do a lot. There’s the public stuff — the big numbers and the specific fabs. Then there are things in the background that people don’t focus on or don’t even know about: moving certain technologies here, agreeing to provisions in their deals around supply chain, upstream, and downstream that will strengthen the ecosystem very significantly. I feel very good about that.

Jordan Schneider: If we’re going to use TSMC as an example, there is a world in which a president, instead of being happy with a $500 billion number on a piece of paper, says, “If these fabs aren’t built by this date, you’re not getting this.”

Todd Fisher: That, and more.

Mike Schmidt: We did have that — with our money. That was the milestones. But it was within the bounds of the program, as opposed to saying, “If they’re not built by this date, then some licenses get compromised” or other levers outside the program.

Jordan Schneider: It comes back to the independence-versus-leverage question. You say you were pushing them pretty hard. You were mentioning World War II industrial policy analogies earlier. If a war was starting, or if you had ninety percent confidence it was going to start in two years and you needed TSMC to move half of its company to America in six months, there are levers the U.S. government could pull that are very different from tax incentives.

Mike Schmidt: True. Although, from my amateur historian reading on how World War II played out, it was a full mobilization with a huge buildup of state capacity. But the tools were pretty straightforward — the power of the government as a customer and as a financier on the supply side. In the meantime, there was massive political mobilization on the industry side — to win the political narrative coming out of the war and lay the foundation for the type of post-war economic system that the business community wanted.

You don’t read that history and get the sense of executives who were afraid the government would use leverage in one area to compromise their interests in another. You get the sense of the government having its interests, industry having its interests, and ultimately both sides working incredibly collaboratively to get it done — but with a huge amount of friction, tension, and politicking along the way.

Jordan Schneider: What I’m getting at is the dynamic with allied countries that are small, that can be pressured, where the U.S. has an enormous amount of leverage. You were talking earlier about not coloring outside the lines — not crossing streams with colleagues at BIS, not stretching the boundaries of executive branch authority. One of the lessons of the Trump administration over the past year is that the executive branch is incredibly powerful, and the amount of leverage America has over other countries is remarkable.

Maybe it’s better to keep that Pandora’s box closed, because opening it leads to the really dark outcomes we’re seeing now. But I can’t help feeling that however much success the CHIPS Act has had, the current administration is striking the fear of God into these companies in a way that nice subsidies never did. A different dynamic could have been unlocked.

Mike Schmidt: It’s a worthwhile discussion — the intersection of diplomatic and industrial activities and how those two things interact. Our experience was that we had our own lanes with industry. These companies are massive power centers. If you look at the major Korean or Taiwanese chip companies, within their own countries they are not the government — they have their own interests and their own geopolitical positioning.

But in the backdrop of all that, the strategic relationships between countries were always present. For us, those were mostly separate threads, but they were generally swimming in the same direction. As we were doing our Samsung deal, Biden was holding his summit at Camp David with Korea and Japan, creating new strategic dynamics in Asia that were pulling allies closer. We always felt our work fit into that, and I’m sure the Koreans felt the same. We had our lane — dealing with Samsung and SK hynix to secure the investments we needed — and it was part of a bigger picture.

Jordan Schneider: Maybe it’s a question of the difference between looming crisis trend lines we don’t like, versus having six months to actually prepare for something that the president says is important.

Mike Schmidt: But as a political question, the real challenge is — how do you create a sense of crisis before it happens, so that you’re actually prepared?

Defensive vs. Offensive Industrial Policy

Jordan Schneider: You said on another show, Todd, that you did ten times the deals KKR would do in a year in about eighteen months. What do you lose at that pace? What do you gain? What are the trade-offs?

Todd Fisher: You lose sleep, honestly. When you’re doing deals at KKR, you’re out hustling to find the right opportunities. Here, the deals were coming to us, so it’s not a perfect comparison. The more relevant parallel is that once you have an agreed deal, getting it to a final, documented, sign-on-the-bottom-line agreement is hard. Mike just talked about that. It’s also true in the commercial world, but there the boundaries are already set. KKR has done hundreds of deals in its history and has hundreds of agreements with companies. There’s only so much room to go back and forth. That was a real challenge for us — trying to get multiple deals done in a very short period of time.

But it also creates excitement, team dynamic, and a culture of, “We’re just going to do this and get it done.” That’s very energizing. Having everything on the table at once, with everybody working and trying to get it all across the line — that was very positive.

Mike Schmidt: There’s also a question underneath your question. We often talk about process as something that gets in the way of the objective. But to what extent does process, even if it takes more time, actually end up serving the objective?

One thing we’ve hashed over in retrospect — and a little bit at the time, but mostly afterward — is this wonky structural detail. Our CHIPS money functioned mostly as grants. It’s basically free money that companies keep to help offset cost disadvantages relative to Asia so they invest here. But legally, it wasn’t grants — it was under something called Other Transaction Authority. That meant we had much more flexibility than we would have had in a grant context to design the program as we saw fit.

One thing we could have done is come out of the gates and start doing deals immediately. Instead, we put out a Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), created structured evaluation criteria, built an application process with timelines, and built the team around that. That meant we weren’t immediately going to Intel and TSMC saying, “All right, what’s the deal going to be?”

We also used that time to build our team and develop capacity. But there’s no question: the decision to create that structured process cost us time. At the same time, it had a lot of benefits. It put us on footing with industry where companies knew how we were thinking. They knew our objectives from our vision for success. It grounded negotiations in a sense of fairness and rigor, and ultimately built mutual credibility and respect. It certainly provided some political protection — we laid out a process and followed through on exactly what we said we’d do.

All of that is good, but it takes more time. There are people on the team who would think I’m crazy — they’d say we should have just been out there doing deals faster. I get it. But our sense is that it was probably good to bake in some process to slow our roll a bit so we didn’t rush out and do something we’d regret later.

Todd Fisher: That’s right. I believe strongly in that. If your goal is just to get a deal done with TSMC and Intel, then just go get a deal done with TSMC and Intel. But our goal was broader than that.

Advanced packaging is a perfect example. If we hadn’t laid out a process, really gone after that space, and recognized the critical issues in advanced packaging, we wouldn’t have gotten Amkor to invest here. SK would have been a question mark. Those deals are going to be critical to the future.

We haven’t talked about this, and we’re not as knowledgeable on the R&D side. But one of the things on my mind is that right now, as a country, we’re focused on what I’d call defensive choke points — “Oh my God, there’s an issue in critical minerals, we’ve got to address it,” or “We have zero percent bleeding-edge semiconductor manufacturing here.” The next one will be batteries, or drones, or APIs, or whatever it might be.

But what we should also be focused on are the enabling technologies of the future. Advanced packaging is one of them. The industry is changing dramatically. TSMC broadly owns it now, but it’s evolving, and the U.S. can become the major hub for what is essentially the next generation of Moore’s Law. The same is true across many different materials, substrates, and areas where we should be investing more on the R&D front in a more offensive way.

A lot of what we’ve talked about today is how to use industrial policy to plug choke points. But it’s also about how to use industrial policy to think about what will enable the future. Is it going to be humanoid robots? That full supply chain basically doesn’t exist today but could potentially be created in the U.S. and become a fundamental competitive advantage over time. But we’d have to focus on it and figure out what it’s going to take to get there.

Jordan Schneider: The offensive versus defensive split is interesting. On the defensive side, I feel confident that if you set up a Fed-like institution, give them $50 billion, they’ll 80/20 their way there — these are manageable, tangible problems. The money can be directed to solve specific issues, and the technology already exists. But the offensive stuff is different. There are pieces America has that we’d presumably want to keep — global dollarization, TSMC and Intel and Samsung being ahead of where SMIC is. But beyond that, I’m really not sure I trust the government to pick what the next industry is going to be. The answer is probably more that the NSF and NIH need to do their jobs well. It’s a much more amorphous challenge of how to get R&D right.

Mike Schmidt: It is more amorphous and definitely extends beyond our direct experience. But when you start thinking about the offensive side, you also need to expand beyond what you might traditionally think of as industrial policy — or expand your concept of what industrial policy is. Because it’s about technological leadership, dollar dominance, our university system, allies and partners. It’s a broader geopolitical game where we have pretty significant vulnerabilities that have emerged vis-à-vis China. They’re going to continue investing, continue looking for ways to create more vulnerabilities or shore up their own.

Todd Fisher: We have to do the same. Those vulnerabilities emerged because China took a more offensive approach. The fact that they identified the electric vehicle supply chain as critical — particularly the enabling technology for EVs like batteries, which are also essential for drones, robotics, and more — that positioned them well. What I’m saying is there’s a role for government to incentivize and encourage some of this activity. Obviously there’s a lot of venture capital. We have so many great advantages in this country — deep financial markets, deep venture capital, innovation, phenomenal design capability. But the government has a role to play in complementing all of that.

Mike Schmidt: We are just so far behind on the manufacturing side that when I think about manufacturing activity, I immediately go on the defensive. Maybe in that context, there are some areas where we can carve out our own sources of leverage. That’s why my head ends up going toward these other dimensions — it’s not just about manufacturing. But I agree with what you’re saying.

Jordan Schneider: This is maybe the fundamental question of the 21st century — can you R&D your way out of needing manufacturing scale? That’s very much an open question.

Todd Fisher: Why can’t you R&D your way out of manufacturing scale? The whole AI revolution is going to disrupt so many industries, including manufacturing, and we should be — and are — trying to take advantage of that. We have a lot of the skill set to do it.

Take printed circuit boards as an example. We couldn’t fund them through the CHIPS Act because they’re not semiconductors. But if you look downstream from the chip, every chip has to land on a printed circuit board. At least sixty percent of those boards are manufactured in China. As AI has gotten deeper and more compelling, the complexity of those boards — the multi-layered nature of them — has become more important, and they could become a choke point in data centers.

The challenge is that right now, it’s almost impossible to figure out how to meet those costs competitively in the U.S., even with reasonable subsidies. But can you redesign the manufacturing process? Can you not only automate but really rethink it? Are there other tools? That kind of innovation can take a very significant amount of cost out. If we’re able to figure some of those things out, we can be much more competitive in manufacturing at scale.

Risk Aversion and the Solyndra Mentality

Jordan Schneider: I get pitches in my inbox all the time from startups trying to solve the rare earth problem with some new manufacturing technology so we don’t have to dig the next hole in the ground.

Mike Schmidt: Sounds like you have an interesting inbox. I take it they want to come on the show?

Jordan Schneider: They want Congress to notice them. It’s great. But the question is, if you’re sitting in your American Resiliency Fund, how much money are you spending on these breakthrough technologies versus the mine in Montana? You’d have to make an expected value calculation. What would history tell us? We don’t need guano anymore.

Maybe if demand gets tight enough, sufficient scientists, money, and energy will converge to solve these problems. But the issue is there isn’t money for this stuff because it’s so cheap.

Mike Schmidt: A couple of things on that. One is creating incentives or structures on the demand side so that demand isn’t just being driven to China — so it’s naturally being pushed toward, if not the United States alone, a broader ecosystem of countries outside of China.

In terms of what we do, if we’re going to pursue this on a broader scale — and it’s foundational to our competition with China — we have to get comfortable with the notion that not every bet is going to pay off. That’s true at the company level, and it could also be true at the industry level. Rare earths are a crisis now. We should do those deals. But should we also be doing deals that make those deals look bad in retrospect? Yes! We should be pursuing bets that leapfrog whatever the current technology is.

That’s okay. It’s okay to have some bets pay off and others not, as long as overall we are orienting ourselves strategically to deal with a really significant challenge to our power.

Todd Fisher: That’s not an easy mindset and culture to shift. The whole Solyndra mentality — I don’t know how many times we heard that term. It was constant.

“We can’t have another Solyndra” became code for being really risk-averse. But government money exists precisely because the private market can’t fill that gap, which means you’re inherently taking on more risk than private markets would. Some things are going to fail, and we need to figure out how to build a government culture and oversight approach that’s comfortable with that.

I want to ban the word “Solyndra from government.” It drives risk aversion and prevents people from taking smart bets. The same Loan Programs Office that funded Solyndra also funded Tesla. On an overall basis, that fund did fine — and if you had included some upside sharing or equity, it would have done phenomenally.

Jordan Schneider: I’m just trying to think — would I rather have had Tesla go bust?

I wanted to come back to the CHIPS Act dealmaking side. You mentioned AI tooling. This seems like something that’s very hard to automate. What percentage of the work do you think could have been automated?

Mike Schmidt: Very little. Just to give a sense of scale — I’ve been reading books about World War II, and you’ll come across a passage like, “There was this big challenge, so they spun up a bureaucracy of 25,000 people to solve it.” Our team was 180 people managing $39 billion. A pretty lean organization.

Once you get the deals done, there’s a whole post-award phase — the monitoring piece. We only had maybe a couple of months of post-award experience after getting deals closed and cash out the door. But that ongoing monitoring feels like an area where there might be some opportunity for automation. Maybe in due diligence as well.

Jordan Schneider: There’s a whole universe of investment banking work where the percentage of the junior banker’s job that AI can handle is growing over time. But the bigger point is that it feels like there’s something fundamentally human about the way you set things up — where you actually need to deeply understand the individuals on the other side of the table representing the companies.

Todd Fisher: Ultimately — and maybe this is what’s being compromised right now — it’s about building trust between the private sector and government. What companies were nervous about was: “We trust you, but we don’t know who’s going to be in your seat in a year, let alone five or ten years.” If we’re going to do industrial policy well, the private sector and the public sector need to trust each other in the way Mike described from World War II — people collaborating in trusting relationships while still being competitive and pursuing their own interests. We created that dynamic, and you can’t build it on anything other than a human level.

Mike Schmidt: There’s no replacement for that. Although I will say, I made some really bad slide decks that would probably look great now with AI. Should I pull these out? I was just a big text-on-the-page guy.

Todd Fisher: Well, Mike was better at it than I was.

Jordan Schneider: My wife refuses to download Claude for Excel. I was trying to sell her on it — “Don’t you want to just try it out?” Her argument was, “If I don’t build the model myself, I don’t know what the numbers are.” Working backward doesn’t force you to do the thinking — to actually put the assumptions in your brain down on paper.

Mike Schmidt: That’s a fair point. Todd, when we got our jobs, the first few months — in addition to putting together the vision for success, thinking through how the process would go, designing the application, all the work on the NOFO, building the team — we did a lot of engagement. We probably had 15 different calls with people in the finance industry: bankers, private equity folks, equity analysts, just asking about the industry. The cool thing about these jobs is everyone will talk to you.

Then came our early engagements with the companies and the customers. It was a crash course — just absorbing as much as you possibly can. There’s no way to replicate that through reading alone. At least for me, it’s about hearing things over time and then developing little intuitions about what’s going to work, what’s not going to work, and what’s important.

Todd Fisher: And developing those relationships. I would go to investor conferences and do one-on-ones — 15 investors in the course of a day — just hearing their views on the industry and what they thought was going to happen, while giving them a sense of how we were approaching things. There was a long-term benefit to that.

It was really beneficial to us at CHIPS. There were many times we brought a group of investors to DC, sat around a table with Gina Raimondo, and discussed what they were seeing China do. A lot of these hedge funds have eyes on the ground in China, trying to figure out who’s doing what, how many EUV machines are actually there. You can learn a lot.

Mike Schmidt: If a company is giving you a lot of happy talk, Todd being at a conference provided a useful check. We’d talk that night and he’d say, “There’s a lot of skepticism here about Company X being able to do that thing.” That might be right or wrong, but it’s a helpful data point.

Todd Fisher: Same with the customers. Once they realized we were credible people genuinely trying to do the right thing, the relationship changed. If you look at the Venn diagram of our interests versus theirs, it was almost a complete overlap — they needed more supply. We ended up with really collaborative discussions that gave us a lot of information and knowledge, allowed us to understand what was going on, and empowered us to push harder: “Why don’t you try this? Why don’t you try that?”

That’s what a separate national investment bank — or whatever you want to call it — could offer. The advantage of building those relationships and having that credibility would be really valuable. That’s something most people don’t focus on when they think about the kind of work we ended up doing.

Mike Schmidt: But I’d guess that folks at the Department of Energy working on rare earths have developed exactly that. They probably know the ecosystem well, know the targets. I bet they’re doing it all.

Jordan Schneider: An interesting contrast is that you two did not come at this with deep sector experience — you hadn’t worked in the chips industry for 30 years. You added people to the team who did have that background, but the leadership came from elsewhere. On the R&D side, it was different — there were leaders who had spent 25 or 30 years living and swimming in this world. Without speaking about them specifically, what were the advantages and disadvantages of coming at this without having spent 20 years at Intel or investing in chip stocks?

Mike Schmidt: The disadvantages were very clear. We had to learn a lot in a very short period of time and develop credibility. I had a very explicit conversation with Secretary Raimondo about this when she offered me the job, because I wanted to be fully transparent with her — I did not have a background in some of the domains that seemed relevant for the role.

What she said was, “For this role, I want someone who knows how to get something done in government. That is its own craft.” She said I’d figure out what I needed to figure out, and we would build the team. To build that team, you needed a whole bunch of things — commercial financial expertise on one hand, and industry expertise on the other. That ended up being the project.

Really importantly, building the team was a department-wide, administration-wide effort. Todd came in as Chief Investment Officer. Donna Dubinsky, a very successful Silicon Valley entrepreneur, had been recruiting people for months at the Commerce Department and handed us a list saying, “I think you should hire these people.” Many of them did end up on the team.

In the early days, we had monthly meetings in the West Wing with Brian Deese and Jake Sullivan. The first topic on the agenda was always the team. If there was a target we were trying to recruit, we would lean on them for help — “Hey Jake, can you take your phone right now and text this person? Don’t put it away until you do.” And they would.

Raimondo — one of her many talents is attracting talent. To her tremendous credit, she was obsessed with getting good people in, and once you identified someone, she was obsessed with closing them. There was never a time where I said, “Secretary, I need you to take 15 minutes with this person to help me close the deal,” and she didn’t do it. All of that came together to build a pretty awesome group of people with the expertise we needed.

Jordan Schneider: From your perspective, the upside was that you can’t be a semiconductor expert and know how to get things done in government?

Mike Schmidt: You could be, but that person didn’t exist. Maybe they did and maybe they would have done a better job.

Todd Fisher: Whether you have semiconductor experience isn’t really the point. As we discussed earlier, the deck is stacked against you. The way government is currently set up, the deck is stacked against you when it comes to getting big things done in a compressed period of time — particularly when you’re starting from scratch and have two, two and a half years to build a team, build a process, build a system, get money committed, and start getting it out the door. That’s a Herculean task even outside of government. Inside government, the odds are even worse.

Part of what Competing with Giants is all about is how to unstack that deck so these things become easier to do in government. The critical thing from a leadership perspective isn’t just knowing how to get things done in government — though that’s part of it — but having a maniacal focus on project management, prioritization, pushing things forward, breaking down barriers, operations, and process. That’s the thing. If you also happen to be a semiconductor expert, great — but you can find the semiconductor expertise separately.

I’m never going to be a pure semiconductor expert, but we learned enough to have credibility. That’s the lesson from my career in private equity. Over the years, I did retail deals, chemical deals, financial services deals. You learn what makes a good investment, what questions to ask, and how to be a curious person — who do I need to find the answer from, how do I network, who do I bring onto the team or contract as consultants to answer the questions I know I need answered but am never going to be smart enough to figure out on my own?

Mike Schmidt: That’s the trick of investing. On the question of expertise, a couple of things. My successor, a woman named Lynelle McKay, came from the industry with 25 years of executive experience. She stayed for close to nine months after I left, serving as director of the program in the Trump administration. She had that industry background plus a couple of years of government experience working on our team. She did unbelievable work and then led the team. There are different profiles that can work — but in that startup phase, having government execution capability was probably really important.

The other thing I’d say is the semiconductor expertise we needed didn’t just come from the industry. Perhaps one of our most valued experts on specific technologies came from the intelligence community — deep, specific knowledge of how different technologies would be used in different national security contexts. On every deal we did, we’d go to him to understand why a particular technology mattered.

Todd Fisher: We also had an investor on the team who had been doing semiconductor investment — he’d never been in semiconductor fab manufacturing or engineering, but he had a completely different network of people. That breadth of networks across different parts of the economy gave us a lot of advantages.

On America’s Chemical Industry

Jordan Schneider: Let’s take a chemicals detour first. Chris Miller was texting me the other day: “Chemicals is an industry no one in the policy world understands. China’s crushing it, and it’s probably on the cusp of major transformation and R&D driven by AI. The traditional petrochemicals are being crushed by China. BASF is losing production. Korean players are non-existent. But America is starting to be more viable due to low natural gas prices.”

Todd Fisher: He’s talking about a very specific part of the chemical industry. Petrochemicals in East Asia involve massive capacity. But when you think about chemicals for the semiconductor industry — which is all upstream — that’s not solely, but significantly, about very small specialty chemicals like photoresist esters, for example. That’s a whole different way to think about it.

Mike Schmidt: Very, very different. We struggled a little with those because they didn’t get the investment tax credit. To the extent we could incentivize them directly, those were mostly smaller deals that didn’t get done while we were there and are still sitting on the table. The hope was that by creating enough of a demand signal through operations at the major fabs, the suppliers would want to co-locate over time.

Jordan Schneider: Todd, when we talk about doing industrial policy in giant, sophisticated industries versus the small, struggling ones — when you think about the people you had across the table at Intel, TSMC, and Micron, these are high-flying industries with very strong competitive dynamics. The execution risk profile is completely different from a mine that hasn’t existed for a while and may not even be viable. From an investment perspective — something you’re always thinking about in private equity — how did that factor into the CHIPS Act work, and how would it need to factor into the long tail of industrial policy challenges?

Todd Fisher: It factored in very significantly. Maybe the first conversation — certainly one of the very early conversations I had with Secretary Raimondo — was: “We’ve got the world’s most sophisticated people across the table from us. They have unlimited resources and can hire the most sophisticated advisors and lawyers. We need to face off against them in a highly credible way.”

That shaped how we hired. It shaped team structure — something Mike and I talked a lot about up front. There are many different ways you can structure a team, and we ultimately chose to organize it more like a typical investment firm. Small, dedicated teams facing off against each company — one team deeply getting to know Intel, another for TSMC, another for Samsung, and so on.

It also shaped the kinds of advisors we brought in — a whole other topic in government, and a crazy process. But I was very focused on making sure we had an advisor by our side, so that if a company was going to bring Goldman Sachs to tell us why we were wrong, we had someone of that caliber on our side.

A lot of the upfront design work connects to what we discussed earlier about whether legislation should give flexibility or hem you in. That flexibility allowed us to step back and say: given this industry, this set of applicants and customers, what do we need? How do we structure the team, hire the right people, and create a process that ensures our independence?

It also drove some specific design choices. I’ve written about some of these, but our upside-sharing mechanisms — a form of equity — were designed not only to protect taxpayers and capture value if companies did far better than expected, but also to align information asymmetries. We wanted to ensure there was no incentive for companies to tell us the numbers were either too high or too low — there was an incentive to give us the real numbers. We tried to structure the overall program to limit information asymmetries and to be able to sit across the table from these highly sophisticated companies as sophisticated counterparts ourselves.

Jordan Schneider: Thinking about the small-cap companies — one of the big tools private equity firms have is that when they take something over, they can bring in new management. As we start doing more of these equity deals, is there a universe where we really need a company to succeed but don’t trust the person running it, even though they’re the only one with the capital? We don’t have to do the Intel analogy right now, but what happens when you need a firm to do something and the leadership you don’t think can get you there?

Mike Schmidt: There’s a question of legal authority. Does your deal give you the authority to change management? Most of these deals would not. But then there are informal mechanisms — obviously, tweets can do things. What I would say is it should be a very, very high bar. Extremely high. I wouldn’t say never, but the government should have a very high degree of humility about whether it knows enough to decide who is best to manage a company. The strategic interest may never be high enough where you’d feel compelled to do it and confident enough in how to execute it. There are precedents — the auto bailout, where they changed management — but that’s the rare exception.

Todd Fisher: It’s the absolute exception. With CHIPS, we were on average giving these companies 10% of the cost of a project. There’s a whole separate topic of whether you should own direct equity in these companies versus some form of warrant or upside sharing that’s more taxpayer-protective, as opposed to picking winners and losers, actually owning shares, or having voting rights. You get into a very slippery slope, because I don’t think government should be in the business of business in that way.

Government should be trying to figure out what the market is failing to provide — whatever externality or other reason the private sector isn’t willing to fill — and then use government funds and tools to incentivize and shape the market.

We had so many debates about TSMC, Intel, and Samsung. Obviously, TSMC is by far the market leader today. You could argue: put all the money into TSMC because they’re going to get us there. Or you could argue: don’t give any money to TSMC because they’re a Taiwanese company — we should be supporting our own. Our conclusion was that we need TSMC to be successful. They have the know-how. They can help us build an ecosystem. But it’s not a healthy market if only one player can really serve it. We should be encouraging the other two — because there are only two, Samsung and Intel — giving them every possibility of succeeding, and then letting the market sort itself out. That’s a much healthier environment where you’re creating the ground rules and the set of incentives, enabling these companies to compete effectively, and letting the market function.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the emotional relationship to all this, now a year out. Do you drive past the TSMC fab with pride?

Todd Fisher: When you think about the transformational potential, it is mind-bending. If you go to Phoenix and see the pieces of the puzzle coming into place — TSMC, Intel, Amkor, the supply chain, ASU, the local and county governments, the innovation ecosystem developing around it — you can look ten years out and say this could be the equivalent of Hsinchu. That’s incredible.

When you think about what could happen in upstate New York — Micron just broke ground a few weeks ago — the scale that comes with memory and the ongoing investment could totally transform the region. It’s going to take a decade or more, but it’s pretty exciting to think about planting those seeds. Same in Taylor, Texas. These are potentially really transformational investments.

Mike Schmidt: We felt a huge amount of pride. We got our deals done, we were catalyzing investment, and it really was on a good trajectory. But at no point in the process — until maybe a month before the end — did that seem self-evident. It was a grind. The release of saying, “We’ve done our part and we can pass the baton,” felt really, really good.

Then there was definitely a period of uncertainty about this organization and program I’d spent two and a half years obsessing over every day. For a few months, signals about the program’s future would come through — a statement in a speech, different indicators — and I didn’t have the emotional distance to treat any of that with detachment. I just felt attached.

On top of that, DOGE came in and ended up laying off maybe 40 or 50 people. Those were friends and colleagues who joined the team because they believed in the mission — awesome public servants. From a human perspective, that was really tough.

Over time, the program has stabilized. The investment tax credit expanded. Broadly speaking, there’s been significant reinvestment in the program.

Todd Fisher: That’s a little-understood development. The investment tax credit was expanded by 10% in the Big Beautiful Bill. That’s more money than we had to invest through grants.

Mike Schmidt: They also haven’t imposed any tariffs on chips. The actual strategy thus far has been to increase supply-side incentives. We’ll have to see the investment trends over time, but there has been a measure of continuity, and that’s a really good thing — to the administration’s credit, because this is hugely important for national security. Increasingly over time, you just become a citizen like everyone else, paying attention to this part of the world along with all the other parts going through turmoil.

Todd Fisher: For me it was a little different, because Mike left on January 17th and I agreed to stay until March 1st. Those six or seven weeks were challenging. I’d never been through a transition. The day before I was meant to leave, the order came down to lay off all probationary employees, which for us was almost everybody because there was a two-year probation period. Anyone from the private sector who had joined was basically still within that window.

My last 24 to 48 hours were spent fighting to save as many people as we could. We ultimately saved a good chunk — maybe a third or so. But to leave on that basis, particularly on CHIPS, where most of these people had given up careers in the semiconductor industry and the private sector — to feel like they were being vilified, accused of trying to game the system, wondering whether they’d be fired, whether they should take the fork — it was a really difficult environment. When I left, I was shell-shocked. It was a tough, tough time. Everything after that, as Mike said, has been my experience as well.

Very well done

I only have so many hours in a day, but I will always set at least one of those aside to read these fascinating “hands on” stories about industrial policy design and implementation. A few things jumped out from this episode:

- the enormity of managing $39B with-a-B worth of grants. Damn.

- the importance of talent. The importance of talent. The importance of talent.

- very few people discuss the real questions about opportunity costs. Good to see that issue raised here in a way that makes you appreciate that $100B spent in one big and critical area, means $100B is not available to spend in other big and critical areas. Tough, gnarly choices (one that may eventually haunt us when it comes to data center over-investments).

- whatever mistakes the CHIPS team might have made, the fact that the people on the team were above reproach will be an enduring legacy. Especially when compared to the neoroyalism/nepotism driving many current investment and manufacturing decisions. It’s a third rail too many people want to avoid touching publicly. Yet it’s dominating decisions made today.

- Secretary Raimondo’s reputation will only grow over time.

- Browbeating industry works until it doesn’t. Then it fails badly. Maybe a cautionary tale here about the Pentagon and Anthropic.