Is China Cooking Waymo?

China's AV companies are expanding globally and pushing to control the supply chain

In terms of international expansion, Chinese firms are way ahead of the American competition. Chinese companies have worked out Autonomous Vehicle (AV) deployment deals with more than thirteen countries. The US: two. Chinese companies are also exporting something closer to a full autonomy stack — vehicles bundled with cloud services, AI traffic management systems, and road sensors.

There’s also the supply chain. Unlike frontier AI models, where US export controls on Hopper and Blackwell GPUs have genuinely constrained China’s progress, AVs operate in a different hardware regime. Here, the leverage between the US and China is more evenly matched, and in some cases, inverted.

Today’s Content:

AVs in the US and China

The International AV market

Who has leverage in the AV supply chain

At times, this piece reads like a typical “US vs China” article, but in fact we’re seeing more of a “co-opetition” dynamic Kevin Xu highlighted in the AI industry. In fact, the perhaps more interesting aspect is how the line between “Chinese AV company” and “US AV company” blurs in practice. Chinese AVs use NVIDIA chips, Waymo uses Chinese-made Zeekr vehicles, and Uber and Lyft partner with Chinese AV firms internationally, not to mention critical minerals. The industries are too tangled for neat distinctions… but let’s try to untangle them anyway.

1. AVs in the US and China

The US has Waymo. China has its “big three”: Baidu’s Apollo Go, WeRide, and Pony.ai (whose founders ChinaTalk interviewed last year).

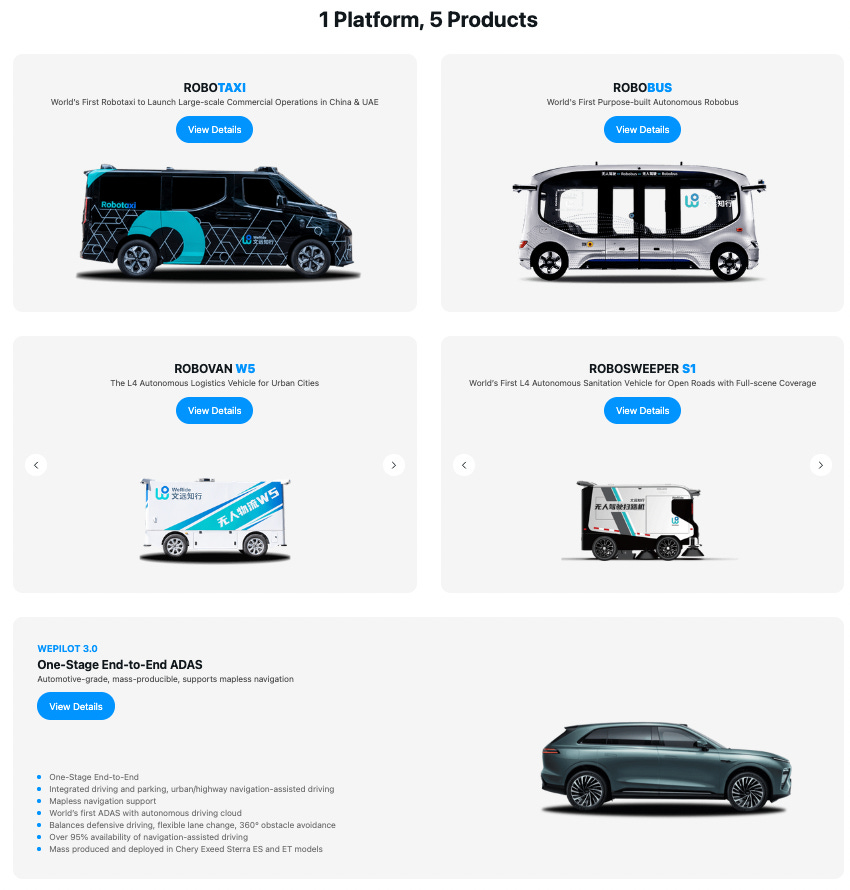

There are other potential players in the US, like Amazon’s Zoox and Tesla (RIP GM’s Cruise). But right now, Waymo is the only American company operating a scaled, paid Level-4 robotaxi service, which enables vehicles to handle all driving tasks within specific operating zones. China also has BYD and Xiaomi with L2 driving features (who could transition to L4 soon), and many more robovan, robus, robodelivery, and robotruck companies on track for L4 deployment.

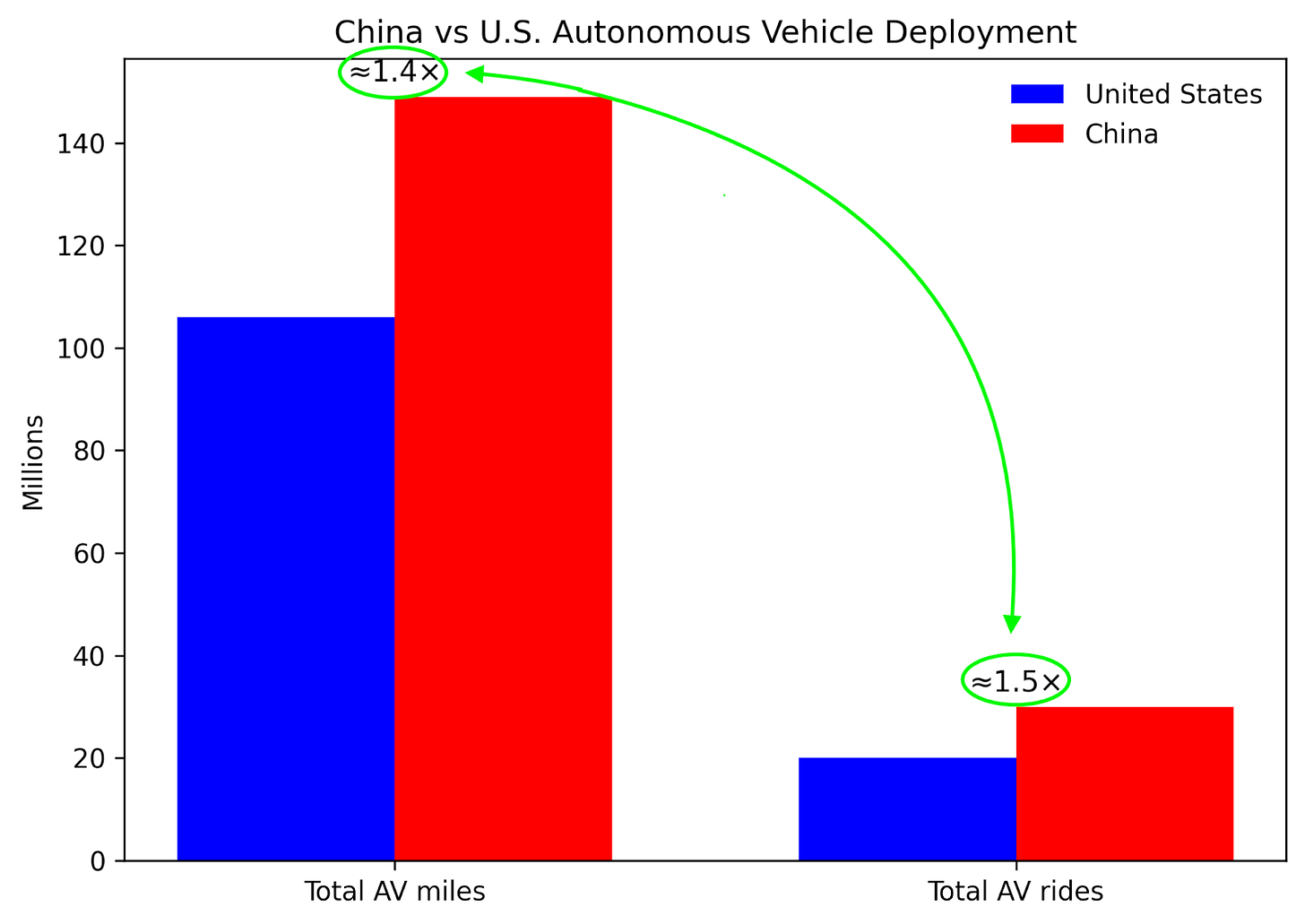

In aggregate terms, China appears to have the edge in overall deployment. An analysis by SCSP suggests Chinese autonomous-vehicle operators have collectively logged roughly 149 million autonomous miles, compared to around 106 million miles for US firms — a roughly 1.4 to 1 advantage.1

But mileage comparisons are limited. Companies report different levels of autonomy, mix supervised and driverless miles, and disclose data unevenly across jurisdictions. Ridership is a different way to look at it, where China has completed ~30 million rides, versus ~20 million for the US (Breakdown in Appendix 1).

Different Services

Ridership itself misses a big part of the story, because China’s AV industry extends beyond passenger ride-hailing. By the end of 2024, more than 6,000 driverless delivery vehicles were reportedly operating across 100+ city zones. Companies such as Neolix, Zelos, Meituan, JD Logistics, and Alibaba’s Cainiao are actively piloting or scaling operations for shipping, food delivery, and street-cleaning vehicles.

The US, by contrast, doesn’t yet have road-going (as opposed to sidewalk-going) driverless AVs deployed, with companies like Nuro still limited to pilots and R&D fleets. They do have an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 sidewalk AVs, but China has many of these also, and they are a much simpler technology.2

China also seems to be leading in autonomous trucking.

Different Environments

A common critique is that China’s pilot zones create an artificial environment, so bragging about its safety record or miles driven is like bragging about avoiding accidents while driving a golf cart around a country club. I think this is wrong.

For context: China has pioneered an ambitious pilot zone strategy, reshaping large portions of cities to accommodate AVs through vehicle-road-cloud integration (车路云一体化). Intersections broadcast signal timing, cameras extend line-of-sight, and cloud systems coordinate traffic flows. These zones feature highly visible stop signs, walkways, and pedestrians, often exclude unpredictable bike lanes and scooters, and were initially launched in lower-density areas.

But Waymo can’t drive everywhere in its pilot cities either. Wuhan’s pilot zones started small but now blanket the entire city, with AVs driving alongside cyclists, scooterers, and jaywalkers.

^Guy rides an Apollo Go vehicle in Wuhan, one of the most ambitious AV cities in China. Also, note that Chinese AVs seem to have much more expansive user experience features, like an AI assistant that can roll down the window or give you a back massage.

There’s also a more forgiving regulatory structure. China’s centralized system somewhat mitigates complications like interstate travel. The US counter is that bullish states can move ahead without federal approval, but the downside is that Waymo burns significant resources negotiating bespoke city-by-city agreements domestically, diverting time from international expansion and raising legal barriers for new companies entering the US market. Chinese AV companies also have to work out separate agreements city-to-city, but with a federal mandate and more lenient legal code, this is still less of a headache than in the US.

Differences In Public Opinion

The survey evidence we have (imperfect and limited as it is) points in a fairly consistent direction: Chinese consumers appear meaningfully more comfortable with autonomous vehicles than their American counterparts. Across multiple studies, acceptance levels in China typically fall somewhere in the 50-80 percent range, while US figures tend to cluster closer to 25-40 percent.

High-profile incidents have, however, exposed real limits to public tolerance. A widely reported crash involving a Xiaomi SU7 that killed three students triggered a wave of public backlash and appears to have made regulators more cautious about how quickly AVs are rolled out.

There’s also a growing undercurrent of economic resistance. In Wuhan, often described as China’s most AV-forward city, ride-hailing drivers have repeatedly complained (you might even say protested) that autonomous vehicles threaten to displace what is, for many, their primary source of income. Those concerns carry extra weight in a weak labor market, where unemployment remains high and alternative opportunities are scarce.

China is reported to have around 38 million truck drivers. In the US, it’s roughly 2.2 million, and the industry faces labor shortages. China also has a larger ride-hailing and food-delivery ecosystem, meaning that when you add it all up, China has nearly twice the per capita rate of workers in occupations at risk of displacement (36.8 vs 20.0 per 1,000 people) [Breakdown in Appendix 2].

2. The International AV Market

The divergence between US and Chinese approaches to autonomous vehicles becomes even more pronounced in their international expansion strategies.

US Companies (i.e., just Waymo currently) have deals with:

Chinese companies have deals with:

The international lead for Chinese companies is larger than it appears, because countries already integrated into China’s Digital Silk Road infrastructure are natural targets for the next wave of expansion. Egypt, for example, is attempting to ditch Cairo by building the New Capitol, with extensive Chinese infrastructure support for “smart city features,” the kind of project that sounds ripe for AV deployment. Similar rumblings have been true for Oman. WeRide also struck a partnership with Grab, the biggest ride-hailing app in Southeast Asia, which positions it well for expansion into the entire subcontinent.

*Note: What counts as an ‘agreement’ is broad. France’s agreement with WeRide for robobus deployments at Roland-Garros isn’t blanketing Paris with robotaxis, but it still shows the buds of cooperation, such as the subsequent deal between WeRide and Renault to deploy Robobuses in France’s Drôme region. Others, notably in the Middle East, are signalling the launch of full-scale commercial operations with hundreds of vehicles and city-wide infrastructure.

Middle East

China has the clearest advantage in the Middle East.

What makes the Middle East such a natural fit is that many governments there can reconfigure the built environment and the regulatory environment in parallel to accommodate AVs. The US strategy, thus far, seems to be to drop AVs into existing roads and regulatory systems and hope for the best.

For example, Saudi Arabia signed a deal with WeRide in 2024 to deploy robotaxis across the Neom megaproject. With help from the Chinese, the planned city is being built with dedicated infrastructure for autonomous vehicles. The UAE is doing similar things. WeRide has reportedly accumulated 1 million km of operational mileage in Abu Dhabi already.

Some of these supply-side projects sound overly ambitious (not off-brand for Chinese infrastructure projects), but the crucial difference from Chinese domestic projects is that Chinese companies won’t primarily bear the financial burden if these Middle Eastern ventures turn out to be total disasters. The host countries are paying Chinese companies to provide infrastructure, meaning China profits from its construction expertise regardless of whether demand materializes. If Neom ends up as a half-built, empty city in the middle of the desert with hundreds of AVs and no one to use them, that’s a sunk cost primarily for the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

China would still incur losses from producing the vehicles themselves, but if they only provide the software and key components, like LiDAR, while allowing local companies to supply the base vehicles, losses would likely be limited to $10-20k per vehicle. These vehicles could also be reclaimed and redeployed elsewhere.

Europe

Europe is a more surprising case than the Middle East. Despite the EU’s openly wary stance toward Chinese vehicles — as evidenced by their anti-subsidy probes and tariffs on Chinese EVs — Chinese AV companies are making significant inroads ahead of American competitors.

Is Europe following the same trajectory with respect to Chinese EVs, where regulators stepped in only after there was significant market penetration?

From all my interviews on this topic, the biggest open question people had is what will Europe do next? GDPR already imposes strict requirements on data collection and processing, while the less-discussed Cyber Resilience Act mandates cybersecurity standards for connected products. Both could be used to block Chinese AVs.

The precedent is already set. The US has effectively banned Chinese EVs through the Connected Vehicle Rule, which prohibits vehicles with Chinese or Russian software due to national security concerns about data collection and potential infrastructure mapping. However, China has recently responded with new guidelines exempting foreign-collected automotive data from security assessments, primarily an attempt to assuage European data privacy concerns about Chinese vehicles.

Chinese companies are partnering with local European automakers (like Stellantis) for the base vehicle while supplying the AV-specific infrastructure and software themselves. This approach could help circumvent EU tariffs on Chinese EVs — which would otherwise apply to Chinese robotaxis if they use Chinese EVs as their base vehicle — and positions the arrangement as a joint venture rather than simply dumping Chinese vehicles onto European streets.

3. Who has leverage in the AV supply chain?

China’s Leverage

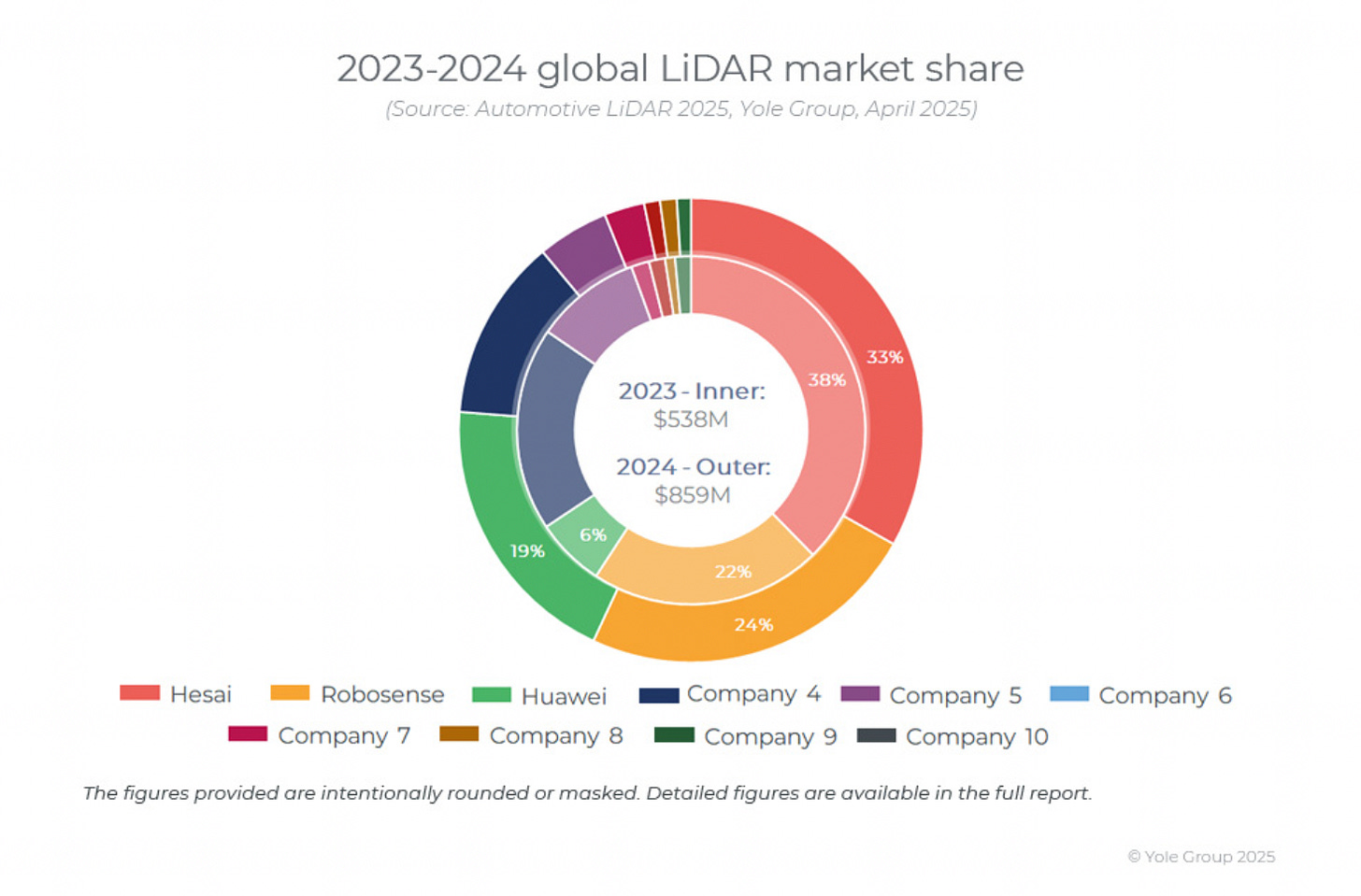

LiDAR uses laser pulses to create detailed 3D maps of a vehicle’s surroundings, measuring distances to objects. It’s the spinning sensor thingy typically mounted on top of autonomous vehicles. China controls ~90% of the global LiDAR market. Firms like Hesai, RoboSense, Huawei, and Seyond account for the bulk of automotive-grade LiDAR shipments.

Waymo, importantly, produces its own LiDAR in-house, so China can’t cut it off. But most of the AV industry lacks that level of vertical integration, and because Waymo’s LiDAR is proprietary, new companies entering the market will likely be beholden to Chinese suppliers. (An AI analogy is Google’s TPUs for AI models; they can produce these for themselves, but a new entrant into the AI game would likely be reliant on NVIDIA’s GPUs.)

Batteries are another potential choke point. Most robotaxis are electric, which pulls AVs directly into the EV battery supply chain that China dominates end-to-end. CATL and BYD together account for over half of global EV battery installations, with companies like Tesla, BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, and Toyota all using them. Even Waymo’s next-generation robotaxis use Chinese-made Zeekr vehicles powered by batteries from CATL.

Interestingly, CATL was designated as a “Chinese military company” by the Biden-era DoD and added to the blacklist for government or military usage. This blacklisting doesn’t apply to commercial vehicles… yet.

These advantages translate directly into cost. Public estimates routinely put Waymo’s current robotaxis at roughly $130k-$150k per vehicle, once sensors, compute, and the base car are included. It is purported that they spend $40-50k just on sensors (like LiDAR), since they are paying a premium to produce it themselves. Chinese robotaxi platforms, by contrast, are cited at $30k-$50k all-in, due to state subsidies and the preexisting car manufacturing prowess.

US Leverage

If China were to withhold access to LiDAR or batteries, how could the US respond?

Most directly through NVIDIA chips, but not the standard Hopper and Blackwell series GPUs used in AI data centers. Unlike data center GPUs designed for training, AVs use automotive-grade systems-on-chip (SoCs) like NVIDIA DRIVE Orin and Thor — integrated platforms that combine CPU, GPU, and dedicated neural network accelerators optimized for real-time inference, safety certification, and lower power consumption. Baidu uses dual Nvidia Orin X chips, Pony.ai uses four Orin chips, and WeRide recently deployed Nvidia’s Thor platform.

However, the technical barriers differ significantly between AI and AV chips. For AI GPUs, cutting-edge nodes (2-5nm with EUV lithography) are essential to achieve the compute density required for training workloads, but autonomous driving chips face lower node requirements. Current AV chips like Nvidia’s Orin operate on relatively mature ~8nm processes, since AV workloads prioritize deterministic latency, power efficiency, safety certification, and software integration over just raw compute density. This means Chinese domestic foundries like SMIC could theoretically produce decent AV chips on 7-12nm nodes without accessing advanced lithography equipment, whereas comparable AI training chips would require the cutting-edge processes that remain out of reach.

I don’t want to underplay it. The upcoming NVIDIA Thor chips use 4-5nm nodes that Chinese companies cannot fabricate through TSMC. And it would be a real headache for Baidu, WeRide, and Pony.ai to switch to domestic alternatives, as this also means switching much of the downstream software ecosystem. But unlike AI training, I also don’t want to underplay that chips aren’t everything for AV infrastructure.

US export restrictions currently limit TSMC to fabricating AI-related chips at 7nm or larger nodes for Chinese customers. AV chips ostensibly fall under this distinction. Several leading Chinese AV chips therefore operate at or above this threshold: Horizon Robotics’ Journey 6P chip, Huawei’s HiSilicon Ascend series (used in its MDC platform), and Black Sesame’s A1000 chip. These chips are proving, at minimum, viable: Black Sesame’s A1000 powers mass-production vehicles from Geely’s Lynk & Co, Hycan, and other major Chinese automakers, while Horizon controls 49% of China’s self-driving chip market and claims more vehicles with Navigate on Autopilot-style features use its chips than NVIDIA’s.

So, NVIDIA has leverage in AV chips, but lacks the stranglehold it enjoys over AI GPUs. I do still believe their chip advantage outweighs the leverage Chinese companies hold with LiDAR and batteries, since China remains fundamentally bottlenecked without access to EUV lithography and other crucial semiconductor manufacturing equipment, whereas the US has demonstrated it can produce LiDAR and batteries when needed, albeit less efficiently and at higher cost than China. However, rare earths and critical minerals add another layer of interdependence, since elements like neodymium and gallium are essential for LiDAR systems and electric motors. Everything is quite intertwined at both the front end and back end of the stack, meaning, for now, both American and Chinese vehicles are reliant on each other.

Conclusion

China’s AV sector is performing strongly — controlling key parts of the supply chain, dominating international expansion, and scaling up deployment domestically. But here’s a puzzle: why did both Pony.ai and WeRide experience brutal post-IPO crashes? Pony.ai fell from its debut price of $15 to $4.18 before recovering to around $16-17, while WeRide plummeted from $15.50 to around $9-10. Their valuations of approximately $7 billion and $3 billion pale in comparison to Waymo’s estimated $110+ billion valuation.

I suspect these conditions can coexist. China’s unique political economy has proven it can (1) dominate a global sector without (2) guaranteeing it is financially lucrative. A similar dynamic has played out with EVs. China produces 70% of global EV output, yet most Chinese EV makers operate at a loss. State-backed capacity buildout created severe overcapacity and price wars, with automaker margins falling from 5.0% in 2023 to 4.4% in 2024 despite surging volumes.

The brutally competitive domestic market may explain why these AV companies are racing overseas. If you strike a deal with the UAE and are the only AV company able to operate there, there is some room to breathe away from the vicious competition within China.

Want to chat about global AV competition? Reach out to me at nick@chinatalk.media

Appendix 1: Estimate of Total Rides

Waymo (US)

Widely cited reporting places Waymo at ~20 million cumulative paid robotaxi rides as of early 2026 (Financial Times)

Baidu Apollo Go (China)

Public disclosures and secondary reporting put Apollo Go at ~17 million cumulative rides by late 2025 (Financial Times, Baidu Press Release)

WeRide (China)

1000 robotaxies (WeRide website)

Conservative implication:

10 trips/vehicle/day → 1,000 × 10 × 365 ≈ 3.7M rides/year

25 trips/vehicle/day → 1,000 × 25 × 365 ≈ 9 M rides/year

Pony.ai (China)

Aggregate implication (best guess)

Apollo Go (cumulative): ~17M

WeRide (implied cumulative): ~3.7-9M

Pony.ai (implied cumulative): ~5-8M

China total: ~25.7-34M cumulative robotaxi rides

U.S. total: ~20M (just Waymo)

There are other small contributors on both sides, but I think these effectively cancel each other out, since none exceed 1 million rides.

Appendix 2: Estimate of Non-Passenger Vehicles

China had 7.48 million certified ride-hailing drivers in 2024, and food-delivery platforms alone support millions more workers. Meituan alone reported 3.36 million average monthly active delivery riders in 2024, many of them relying on these jobs as their primary source of income rather than a side hustle, whereas that number is around 37% of US gig workers. I estimate the Chinese total is something like 13-14 million for food plus ride-hailing services (plus the 38 million truck drivers).

The US has approximately 3-6 million gig workers in these sectors: ~2-2.2 million ridehailing drivers (Uber had 8.8 million drivers globally in Q2 2025 with approximately 1-1.5 million in the US based on historical data) and ~2.5-3 million food delivery workers. DoorDash had 8 million dashers in 2024, but I’ll also discount this because many of them are part-time workers. 72% of DoorDash drivers work 4 or fewer hours per week.

In total, I estimate:

China: (13.5 + 38 million) ÷ 1,400 million (population) = 36.8 per 1,000 people

United States: (4.5 + 2.2 million) ÷ 335 million (population) = 20.0 per 1,000 people

According to the author of the SCSP piece, the methodology involved aggregating the most recent publicly available mileage figures from major AV firms in each country, with hyperlinked sources for verification. Companies without disclosed mileage data were excluded on the assumption that unreported miles would be minimal and wouldn't substantially alter the findings. This approach was necessary because neither China nor the US maintains centralized public records of autonomous vehicle testing, and few alternative datasets are available for comparison.

Serve Robotics alone reports a fleet of 2,000+ autonomous sidewalk delivery robots operating across multiple U.S. cities, making it the largest publicly disclosed deployment of this type. Other US sidewalk-robot operators (e.g., Starship Technologies, Kiwi Campus) operate additional fleets but do not regularly publish consolidated national totals, implying, in my opinion, an overall US sidewalk-robot count plausibly in the 3,000–5,000 range.