Josh Wolfe on Elon and the Tech Right, R&D, and Parenting

This show was good

Has America already lost its dynamism in basic research? Josh Wolfe, co-founder of Lux Capital, joins the podcast today to discuss.

We get into…

Why the Trump-Elon fallout matters less than you probably think,

How much payoff corporate leaders are reaping from their campaign to appease Trump,

The erosion of the U.S. research ecosystem, and how we should think about philanthropic giving amid that chaos,

Parenting, strategies for emotional resilience, why short videos aren’t terrible, and the history of the machine gun

It’s a good interview. Listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

Dreams of the Tech Right Meet Reality

Jordan Schneider: We have to start with Trump and Elon. I’ll let you pick the frame.

Josh Wolfe: I’m going to take a contrarian position — it’s irrelevant. It’s irrelevant because it dominates front-page news and captures everyone’s attention. I joked yesterday that if you were planning fraud or were a terrible company with bad news, yesterday was the perfect day to release it while everyone focused on this inevitable outcome.

People were making predictions six months ago — over/under bets on whether it would last three months or maybe a year.

Jordan Schneider: There were actual betting markets created for this.

Josh Wolfe: Exactly. You were betting under a year, maybe over three months, but none of this was surprising. This was an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object — kinetic chaos was inevitable. Elon served as a useful foil for Trump and did an excellent job helping him win the election. They were strange and unusual bedfellows.

Trump has historically been a strong China hawk, albeit with nuanced moments regarding Xi Jinping. Meanwhile, Elon depends heavily on China in ways people don’t fully appreciate — particularly Tesla’s production levels and the profit margins China contributes.

Jordan Schneider: Well, the China Talks audience understands this, but perhaps not everyone does.

Josh Wolfe: Right, not the broader ecosystem. This creates a significant vulnerability. You’ll see Elon Musk historically position himself as an outspoken advocate of free speech — though whether Twitter was genuinely about free speech is debatable. I’m more cynical about his true aims.

What you’ll never see him discuss publicly is anything about China. He’ll never criticize Xi for human rights abuses in Xinjiang province or regarding the Uyghurs, and he’ll never mention Tiananmen Square. Nothing. It’s “Free speech for thee, but not for me” when it comes to China.

Inevitable clashes were bound to occur. Was this really about the spending bill, or something deeper? When the leaks started — clearly planted by the White House over the past five days about drug use, and then the Epstein connection — it became salacious and interesting for everyone, but none of it was surprising.

My position is that it doesn’t matter. It’s similar to tariffs — Trump campaigned on tariffs, Democrats attacked him, saying he’d implement tariffs that would be economically troublesome. I don’t understand why these developments are surprising when they shouldn’t be.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking about your profession, many people in the tech ecosystem — particularly with the rise of the tech right throughout 2023 and 2024 — pinned their hopes on this man, similar to how Elon did. They hoped that by being inside the tent, they could influence policy trajectory. From my perspective, benchmarking to June 6, 2025, this has been pretty dramatically disappointing.

What are your reflections on that psychological arc? Are these guys all just patsies?

Josh Wolfe: During November and December of 2024, I remember peak rhetoric around the zeitgeist of America’s golden age. All you could hear was “we’re back, baby” and these ridiculous 1980s Top Gun-infused, Hulk Hogan maverick-style videos celebrating America.

Jordan Schneider: Sure.

Josh Wolfe: I told my wife, who runs an activist public hedge fund and manages our personal money, “We need to buy long, deep out-of-the-money puts” because all I heard was “to the moon” and “American greatness.” It felt like an echo chamber of optimism.

Two to three months ago when the tariffs hit, those positions performed very well in our portfolio. We’ve been relatively unaffected on the venture side.

One area where real change is happening — and it’s always dangerous to say “this time is different” — but it feels very different: defense. We’re seeing a combination of a nearly trillion-dollar budget and a huge shift toward autonomous systems, AI-driven software systems, and space satellites. Remember, Space Force was an absolute joke eight years ago.

Jordan Schneider: Okay, we’re pivoting a little…let’s stay on track.

Josh Wolfe: But this is where the venture world has made noise and impact. There are sympathies, appreciations, and influence, particularly in tech and defense.

Jordan Schneider: Sure.

Josh Wolfe: Regarding everything else: you had everyone pledging fealty, taking a knee, and donating a million dollars to the inauguration campaign. Zuckerberg, Bezos, Satya, Sundar — they were all paying homage to Trump, hoping to escape DOJ, FTC, or antitrust scrutiny. How that plays out remains to be determined.

The Trump-Elon situation was both weird and destined to end inevitably. There will be some strange reconciliation, and they’ll be bros again. But I don’t think this is just about the spending bill — it’s much deeper.

Jordan Schneider: One of the things the tech right didn’t price in is what’s happening around immigration and the basic research ecosystem. Let’s start with basic research. There’s this argument that we don’t need the NSF or NIH because corporate R&D has increased significantly over the past 30 years and can drive innovation forward.

As an investor who focuses on scientifically ambitious investing, what do you think the economy gets from basic fundamental research that happens in labs and universities versus corporate R&D?

Josh Wolfe: Long-term: everything. Short-term: it’s hard to see the value. For policymakers looking at budget cuts — particularly those focused on short-term gains — these programs seem like easy targets. This isn’t just a Trump phenomenon. In 20 of the last 22 years, we’ve had federal cuts to federal science funding.

Jordan Schneider: We had a brief moment with the Endless Frontier Act.

Josh Wolfe: Right, it started with Endless Frontier, which referenced Vannevar Bush’s work from around 1945. Then you had “The Gathering Storm” by Norm Augustine, the former Lockheed executive, warning about America’s talent base and cultural shifts in what people were drawn to and celebrating.

What they didn’t mention in that report — now over 20 years old — was this anathema, this zeitgeist against the military-industrial complex, precisely when China was not only embracing but mandating military-civil fusion.

Over the past two to three months, we’ve witnessed a perfect storm. Now you have the politicization of academia. Harvard sits number one in Trump’s crosshairs — some speculate because Barron applied and didn’t get in, creating some Shakespearean vendetta. Whatever the reason, while anti-Semitism was the stated concern, it was far worse at Columbia, right here in New York City, than at Harvard.

According to Nature magazine’s rankings — which publish various metrics including H-index measurements — when you look at the most important scientific publications by institution, the top 10 includes Harvard at number one, but positions two through ten are all Chinese universities.

Fifty percent of AI graduates worldwide come from China. Thirty-eight percent of the AI and computer science workforce here comes from China — not native-born Americans. They’re outpacing native American citizens by 35-37%.

We’re losing the talent game. What should we do to win? What we did in World War II and beyond: attract the best and brightest. Create brain drain from other countries because people are repelled from their home nations.

Eastern European Jews in the 1940s established the Institute for Advanced Study and brought Einstein here. Having the atomic bomb developed here rather than Germany was a net positive for the world. Soviet émigrés in the 1980s escaped communism for capitalism during the Cold War.

We should be stapling visas to every Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Israeli — anyone who wants to come here. We should help their parents immigrate too, because often family remaining in authoritarian home countries becomes leverage that governing regimes use to control whether these individuals can leave or return.

The last Republican I remember discussing this was nearly 20 years ago: Newt Gingrich, who called for tripling the NSF budget. He understood that everything from Genentech (which emerged from the UC system) to Google (from Stanford) was premised on long-horizon scientific research.

This isn’t just computer science — it’s chemistry, physics, materials science, and all the breakthroughs that emerge from these fields. If we knew what those breakthroughs would be, we’d fund them today. But we don’t. We rely on this rich ecosystem in our own self-interest to support brilliant people who generate breakthroughs.

These breakthroughs often result from combining insights from one department with research from a different university. More than ever, this cross-pollination is critically important. We’re ceding academic and intellectual leadership to other countries. China will likely be the greatest beneficiary.

International students used to comprise roughly 25% of our student body. Now it’s down to 12-15% and falling. China is actively recruiting with programs like their Thousand Talents initiative.

This represents the greatest self-inflicted wound Americans have created in several generations.

Jordan Schneider: You had this line: “If the Politburo were drafting America’s self-sabotage plan, they would politicize science and freedom of inquiry, starve young and ambitious investigators of funding, and discourage the best immigrant minds."

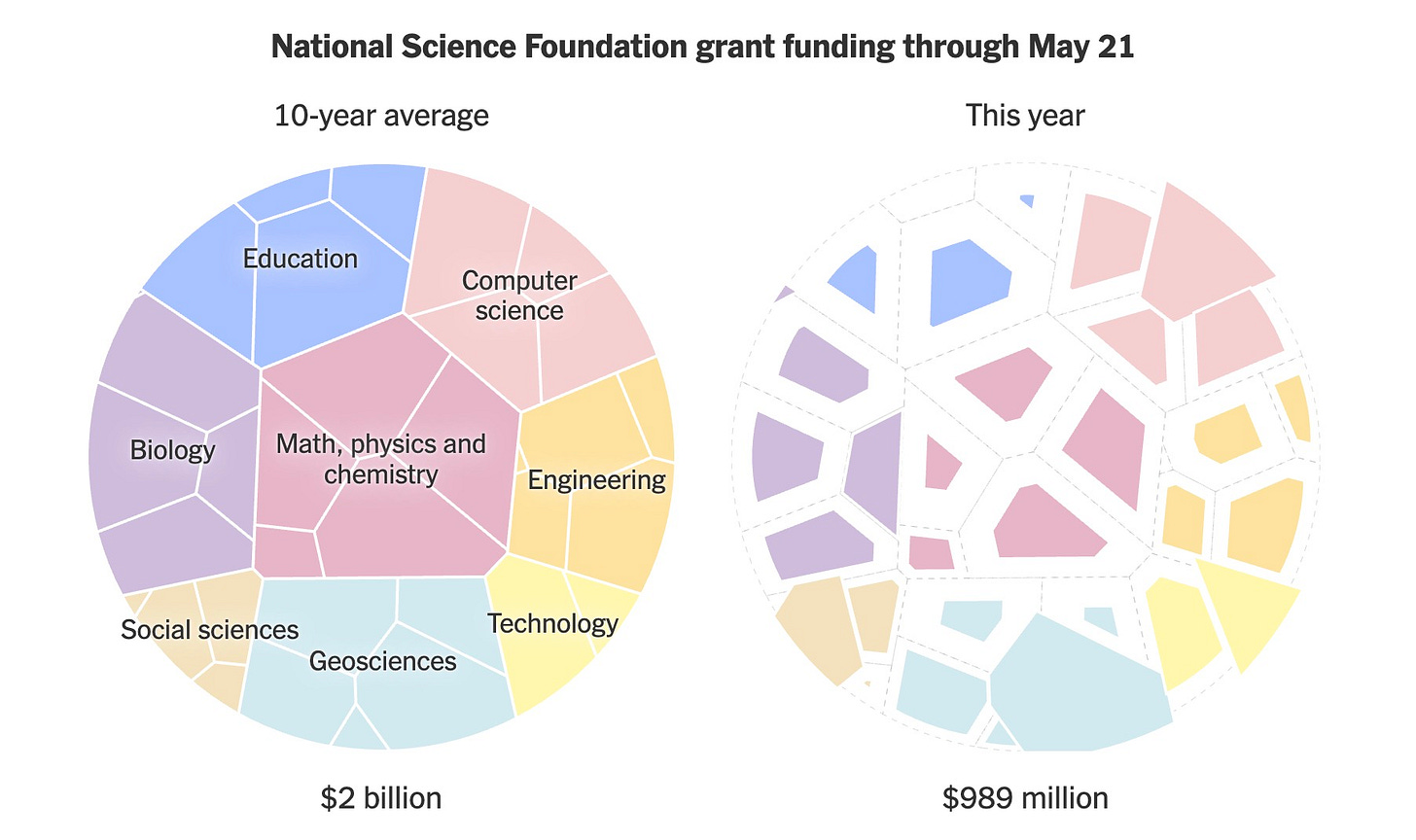

To recap for everyone: the NSF is spending at half the rate it was in 2024, despite authorized funding. The new budget dramatically cuts science and research spending. Universities have been cut off wholesale from billions in research dollars. Johns Hopkins is laying off 1,000 people because they’re worried grants won’t materialize.

Trump said yesterday that we actually want Chinese students, which creates bizarre mixed messaging when his administration simultaneously tells Harvard they can’t admit Chinese nationals.

Josh Wolfe: Some of these grant cuts are both tragic and absurd. There was a researcher studying neurotransmitters for neuroscience whose grants were cut. They couldn’t understand why until they realized the word “trans” triggered a five-letter string search that flagged anything with “trans,” “DEI,” or similar terms.

Now researchers have to change grant language — writing “neurons firing intracranially” instead of “neurotransmitters."

Jordan Schneider: That’s not funny, though.

Josh Wolfe: You’re right. It’s tragic.

Jordan Schneider: Why don’t you talk about the $100 million pool you launched?

Josh Wolfe: It’s specifically not grants because we’re not trying to substitute the charitable giving of our government — funded by taxpayers — which actually makes America great when we have scientists working on breakthrough research.

Historically, about 10% of our investments are de novo new companies, and most emerge from academic labs. We find a principal investigator — a fancy term for a scientist at an academic institution — whether at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Georgia Tech, Cornell, or elsewhere.

The early 1980s Bayh-Dole Act, sponsored by Senator Evan Bayh and Senator Bob Dole, allowed universities to own intellectual property created with federal taxpayer research funding. When a scientist at these institutions files a patent, the university becomes the assignee while the scientist remains the inventor.

We, as a venture capital firm, can license that technology. There’s a well-established deal structure involving licensing royalties and equity — the scientist typically gets about 25% ownership. This mirrors Google’s “one day a week” policy, allowing employees to spend time on personal projects, but applied to exclusive company work.

This approach for launching companies from academic labs is well-established. Professors often stay at their institutions while postdocs handle translational research and join the company. We’ve created about 25 de novo companies this way, spanning everything from 4D lidar for autonomous vehicles to digital olfaction — essentially “Shazam for smell” — to cancer therapeutics and Nobel Prize-winning work from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute that enables real-time cellular imaging.

Historically, this represents about 90% de-risked investment, meaning we take roughly 10% scientific risk. Now, with grant cuts and layoffs at institutions like Johns Hopkins, exceptional research is being abandoned — like proverbial Rembrandts in the attic. Scientists are wondering what to do next. If they wait six months for resolution, they need to find work elsewhere, whether in academia, nonprofits, or the private sector.

Our response is the Lux Science helpline — a bat signal for struggling researchers.

We’re dedicating $100 million from our latest $1.2 billion fund to double down on early-stage science risk. Instead of taking 10% science risk on 90% proven concepts, we’re willing to take 50% science risk on half-baked ideas.

We’ll help license patentable work into our existing companies or arrange sponsored research to continue funding relevant projects. For example, someone contacted us about novel materials for radiation hardening in space. We have 17 companies across the space ecosystem that could sponsor continued research.

Other scientists ready to enter the private sector can work with us to start new companies around their expertise. We’ll license their work, assemble their team, build laboratories, and launch them.

This is just a drop in the bucket — we can’t do this alone. We need dozens, if not hundreds, of other VCs to recognize the value of funding early-stage scientific work. It’s profitable, beneficial for national security, and good for business. Our $100 million allocation, while significant, isn’t sufficient by itself.

Jordan Schneider: I’ve received numerous emails from intelligent people essentially doing backfill work for USAID funding cuts. While it’s admirable that people are donating $10 million or $50 million, tens of millions of people will suffer, and we’re delaying future breakthroughs because we’re not conducting this research. The laboratory animals aren’t being fed, and you need the time, energy, and tacit knowledge built over years of lab work to accomplish meaningful research.

Josh Wolfe: Absolutely. This isn’t purely black and white — there are legitimate concerns about USAID politicization and questionable funding destinations. There are appropriate and inappropriate uses for that money.

My main criticism of the NIH isn’t to strip their funding, but to bias toward young investigators. Too much grant money goes to, frankly, older researchers. Older scientists can be set in their ways and resistant to new approaches.

You need that potent combination of naivety and ambition that drives both entrepreneurial and scientific discovery. Young researchers have the arrogance to say, “I know better than you — why wouldn’t we try this?” while older researchers respond, “Why would you do that? I’ve tried it ten times and it never works."

I would restructure the NIH budget and federal funding to favor younger investigators.

Jordan Schneider: I wonder to what extent the Silicon Valley tech ecosystem that embraced Trump and the DOGE energy — which led to all these cuts — stems from the fact that for the past 20 years, you could make the most money by being 19 and writing software. That’s not something you necessarily need a PhD for. The social returns to that work are very different from what you see when making novel materials and drugs.

Josh Wolfe: Absolutely. Even the term “engineer” shifted from physical engineer to software engineer. For at least 20 years post-internet boom — through the SaaS enterprise boom and cloud boom — that was the dominant paradigm.

Lux was on the periphery of that trend because we don’t really fund software. About a third of our investments focus on healthcare, biotech, robotic surgery, and medical devices. Another third covers aerospace, defense, manufacturing, and industrial applications. The final third is what we call “core tech,” defined more by what we don’t do — very little internet, social media, mobile, or ad tech.

Great fortunes were made and great companies built during the software boom. Interestingly, there’s a China parallel here. Fifteen years ago, Xi Jinping designated software as a domain China would fund heavily. This created incredible companies and ecosystems, and many US investors funded them, believing China was a democratizing, growing market. Knowing what they know now, it would be difficult to justify investing in companies like ByteDance.

Jordan Schneider: Unless you’re Bill Gurley [who recently funded Manus AI].

Josh Wolfe: I love Bill, and he’s not necessarily part of the partnership decision. We’ve discussed this, and he would argue there might be scenarios where teams like Manta are trying to exit China. I think this deserves more study rather than just criticism. However, I personally wouldn’t invest in Chinese companies that are part of CCP military-civil fusion.

The shift also happened within China. At the last Politburo gathering about a year and a half ago, the people close to Xi weren’t software engineers or computer scientists — they were from space, biotech, rockets, and defense. All hard sciences.

This coincided with when Jack Ma went to “spend time with his family” and when entrepreneurs were capped at $9.9 billion. Anyone exceeding that threshold was essentially decapitated — they could start schools or enter education, and either they or their family could leave the country, but not both simultaneously.

The new directive became hard sciences. I used to joke that if you wanted to make money, the greatest capital allocator wasn’t following Warren Buffett or Seth Klarman or other great value investors — it was listening to what Xi Jinping was funding, because that’s where the world was heading.

I agree that for the past 10-15 years, the focus has been software. Many VCs, including Marc Andreessen who said “software is eating the world,” were drawn to Trump partly because they felt rejected by Biden. They were spiting Biden and possibly spiting themselves long-term.

I still believe the greatest entrepreneurs don’t really care about political developments or the 10-year interest rate. They’re building something because they have a chip on their shoulder — and as I always say, chips on shoulders put chips in pockets. They’re driven by private ambitions with timeframes that supersede one, two, or even three presidential cycles.

I remain bullish on great entrepreneurs. There’s simply a shift from software to hardware.

Jordan Schneider: Something worth exploring is the importance of tacit knowledge in hardware versus software and the learning that happens almost entirely in universities during master’s and PhD programs. When you’re doing actual scientific work, you need some sense of navigating the dark forest.

Josh Wolfe: That’s absolutely true. This applies even to semiconductors and manufacturing. TSMC’s Arizona facility is starved of talent — not just union workers doing physical assembly, but specialized expertise. There’s a scarcity of talent because much of that tacit knowledge remains in Taiwan and is difficult to transfer here.

You see this dynamic in companies working on the most sophisticated technologies. My partner Sam Arbesman, who you know or have spent time with, is a brilliant scientist-in-residence here. He has a new book coming out called “The Magic of Code,” and his previous book “Overcomplicated” offered a modern version of “I, Pencil” — the thought experiment about complexity.

If you were to make a semiconductor today, or an Apple iPhone, consider the number of components, the tacit knowledge required, the number of countries and companies involved — it’s extraordinarily complicated. No single person can make a pencil, let alone a semiconductor, chip, GPU, or field-programmable gate array.

Culturally, we get what we celebrate. For 25 years, we at Lux have complained that American culture celebrates celebrities — the Kardashians, the Hiltons, and similar figures. You see this manifested in TikTok and what gets fed to American users versus what’s not even allowed in China and what China celebrates in terms of STEM education.

We’re losing this battle terribly. Looking at the labor pool: we have 300,000 undergraduates in science here. China graduates approximately 1.2 million. Half of our 300,000 are foreign students.

This represents a cultural crisis regarding what we want our children doing and celebrating. We don’t need more people in marketing, advertising, or selling products. We need people inventing things that everybody else in the world wants to buy.

Jordan Schneider: And podcasting.

Josh Wolfe: But you produce intelligence and insight, which is valuable. It’s unique insight because, as you noted, people who follow China Talk understand things that others don’t. That’s an advantage — you produce something intellectually valuable.

Jordan Schneider: Back to the narratives. There was this fascinating Twitter exchange a few days ago. You mentioned the atomic bomb and the Apollo program, and J.D. Vance framed it as “we didn’t need foreigners to do this — we had 600,000 Americans weaving the wires to connect everything together."

Both perspectives are true: his narrative about American workers is accurate, and your narrative about leading lights of both the rocket and nuclear programs coming from Europe is also true. But this narrow-minded “you have to be born here to be part of the circle” mentality — let’s discuss what that means.

Josh Wolfe: This created a significant fissure. People entering the administration who were immigrants from India were being lambasted by these self-described “heritage Americans.” Elon defended them because he’s an immigrant himself — not the classic immigrant from poverty in India or Russia, but an immigrant nonetheless.

He argued there’s a distinction between immigrants crossing the border and taking blue-collar jobs — who may not conform to American society and could include criminals or drug dealers — and brilliant people making extraordinary contributions. For example, the recent genetic medicine breakthrough that cured a baby using one of the first in vivo genetic editing approaches involved two scientists, one whose parents arrived from India 40 years ago. Thank God those individuals came here and had children.

We want this brain drain — from World War II through the Cold War to our current version of Cold War competition. I don’t understand why people consider “immigrant” a dirty word. Immigrants literally are the fabric of this country.

One of my mentors who put us in business, Bill Conway, who founded the Carlyle Group, focuses his philanthropy on addressing one of America’s biggest problems: nursing shortages. He says if you’re anti-immigrant, good luck getting sick, because our entire healthcare system depends on immigrants playing critical roles — from hospital orderlies to doctors to neurosurgeons.

We want the best and brightest coming here. It’s a complete self-inflicted wound to say “America First” means shutting out talent. America First doesn’t mean America Alone, as Scott Bessent has said. Scott is one of the great adults in the room and a friend.

People ask why Scott doesn’t speak out more publicly on these issues. Scott is a student of markets first — he understands currencies and countries — but he’s also a student of human nature. He understands in a Shakespearean way who his boss is, who he works for, and how to manage that relationship. We want him doing exactly that because we don’t want him out of the job.

Jordan Schneider: We discuss immigrants and science frequently on China Talk from a US-China competition perspective, and that’s all valid. But the fact that people want to come here is remarkable. Look, at the margins there are legitimate concerns about completely open borders, but limiting human flourishing by building walls and splitting families is just —

Josh Wolfe: I’m going to be blunt because I come from Brooklyn: this approach is counterproductive and self-defeating. The idea that we’re limiting the immigration of brilliant people who could make this country better is fundamentally wrong.

Our greatest export isn’t our music, Hollywood, fashion, high-tech companies, banking system, or rule of law — it’s the American Dream. The American Dream is arguably our greatest export; it’s what everybody wants. The measure of a great country is whether more people want to enter than want to leave.

Walter Wriston said, “Capital goes where it’s welcome and stays where it’s well-treated.” This applies to both money flows and people flows. I hope the rhetoric will change and that there will be enough great American leaders to counter jingoistic “America First” voices.

There’s a delicate balance: we must remain that shining beacon on the hill, attracting people while distinguishing between good people who genuinely want to build better lives here — who want to embrace the American Dream and become proud Americans — and bad actors who want to undermine the country. Many of the latter are coming through our university system and may be funded by foreign actors, but that’s a separate issue.

There’s virtue in virtuous people coming here and the American Dream being upheld and celebrated. Right now, we’re casting shadows on that dream.

Jordan Schneider: You opened by saying the Elon-Trump fight is noise. But the signal is that people around the world would rather live here than in China.

Josh Wolfe: They still do. My wife mentioned recently that many countries hate us right now — Canada, tourism is down — and there’s probably some schoolyard “arms crossed, I’m not playing with you” attitude.

Jordan Schneider: Sure.

Josh Wolfe: The reality is, I read about how Canada supposedly hates us, then the next headline I see — because I read many papers each morning, including the Globe and Mail — is “Canada wants in on Iron Dome."

The rest of the world, even if they hate us, still wants our superior military technology. The zeitgeist of popular antipathy will fade, but people will still want our materiel — our military materiel.

Jordan Schneider: We’re recording this a few days after the Tiananmen anniversary. The fact that hasn’t happened here — the fact that there is free speech, elections, due process, and habeas corpus — represents incredibly powerful long-term advantages. These aren’t just abstract principles — they’re things that make life worth living and make you excited to get out of bed in the morning.

Josh Wolfe: I remain relatively optimistic personally. I’m always optimistic about technology, science, and ultimately the human condition. I’m always skeptical about people because I’ve read a lot of Shakespeare. Technologies are amazing, science is amazing, and both will continue to progress. People generally disappoint because they’re vainglorious, full of ego, petty, jealous — they connive and deceive.

People ask how I can be optimistic yet cynical. That’s the pairing — I’m optimistic about science and technology, skeptical about people. I love Tom Wolfe’s answer when asked why he writes about space, astronauts, and moneyed Upper East Siders but not politicians. He said politicians are like passengers on a train, and the country is the train. The tracks might go up and down, but it’s generally heading in the right direction over time. Inside the train, there are clowns on one side in red and clowns on the other side in blue, throwing pies at each other nonstop. Every four years, the engineer changes, but the train stays generally on track.

I take that view: the real thrust comes from people, values, that great beacon on the hill, the American Dream that attracts people here. We shouldn’t deter them from building here on that track. Most entrepreneurs couldn’t tell you much about the political system or what’s happening at the Fed or Treasury — they’re focused on building.

Jordan Schneider: But the fact that they have to worry now, that they have to fear their visas getting revoked — look, in other moments that might be manageable. But within our range of expectations, there are definitely scenarios where an executive acting alone can really bend those train tracks.

Choosing Optimism + Parenting

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of Shakespeare, we did a show with Eliot Cohen about his wonderful book The Hollow Crown and another episode as a Biden emergency discussion. The Trump-Elon situation probably deserves its own Shakespeare emergency episode.

Derek Thompson told me to ask you this question — does America need a Gen Z Marsha Linehan?

Josh Wolfe: Marsha Linehan is one of the founders of CBT — Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

I love Derek. I got into psychology maybe five or six years ago. My kids are 15, 12, and 9. My oldest daughter is much more like me — emotionally volatile. I’ll have high highs (not bipolar…emotive!) then calm down. My wife and middle daughter have slow burns with grudges lasting three or four days.

We learned CBT and DBT techniques as a family. Derek’s question is whether Gen Z needs this — I think they do. CBT is essentially Stoic philosophy in a clinical psychology setting. I wish I’d learned this 20 years ago as a kid or teenager — I would have had healthier relationships. I wish I’d learned it 15 years ago before my first child was born — I would have been a better parent. We have a better marriage, family relationships, and even professional interactions because of these principles.

First, avoid extremes like “you always do this” or “you never do that.” If I said “Jordan, you’re always late for podcasts,” your first reaction would be defensive because it’s not true — nobody “always” or “never” does anything. People shut down and become defensive. You want to find the dialectic, avoiding black-and-white thinking. “Sometimes I feel frustrated when you’re late” is much more effective.

Second, when someone has an emotional outburst, they’re dysregulated for various reasons — hunger, a bad day, a lack of tools. If my daughter has a fit, she’s not thinking “I really want to have a tantrum and lose my phone for a week.” You appreciate that they’re doing their best with what they have — they just lack the tools.

Third, validate emotions. When someone’s really upset about something, you could say, “That’s ridiculous, it’s just a math test, you’ll get an A.” But explaining away someone’s feelings doesn’t help. People need validation. They become more emotionally frustrated when they don’t get that release valve. Saying “I can see you’re really upset” sincerely can help reduce their emotional burden.

Returning to Derek’s question about Gen Z, many people seem massively oversensitive. I grew up in Coney Island, Brooklyn, where people talked trash to each other, were rough around the edges, and the world wasn’t safe. You could say all kinds of things. I’ve raised my kids similarly — I don’t want them so soft that when someone says something offensive, they appeal to authority, running to school or teachers saying “he said this” or “she said that.” Take care of it yourself. Have a conversation. I’m not advocating violence, but handle yourself.

My kids have experienced this and tell us about various scenarios. The younger generation — whether you call them far left or woke — has lost some ability to engage with people. When encountering ideas or comments they disagree with, there’s hysteria.

I was a center-left Democrat my entire life. I didn’t vote for Trump, but I also didn’t vote for Kamala. I voted for Bloomberg-Romney, which was not a ticket, but that’s where my values aligned, in a non-swing state where my vote didn’t matter. I had the luxury of voting with my conscience.

I believe many center-left Democrats didn’t move right because they were attracted to the right. They were repelled by the histrionics, noise, whining, and complaining from the left. Enough was enough.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stick with parenting. You mentioned earlier that Steve Jobs accomplished incredible things, but everyone around him in his personal life had a totally different experience.

Josh Wolfe: They hated him. This is a fascinating phenomenon.

Jordan Schneider: This really resonated for me when I was reading a biography of Richard Holbrooke — the most storied American diplomat of the second half of the 20th century, though perhaps not well-known in the Asia-watching community. There was a line where his kid said his father wouldn’t recognize his grandchildren in a toddler lineup.

Growing up, I dreamed of being Secretary of State or a diplomat, but trading family relationships for that achievement gave me pause. Many people choose one path over the other. What are your reflections on this dynamic of accomplishing big things while being awful to the people closest to you?

Josh Wolfe: I used to debate this with one of my best friends, a famous journalist, who talked about how great Jobs or Elon were. My response was that the people around them — their families — hate them. They’re celebrated by strangers, feeling love from millions of people they’ve never met who celebrate a caricature of who they actually are. Meanwhile, their true character is loathed by those closest to them.

I’ve admired something I have to admit I’ll never achieve — I am too rough around the edges, have burned too many bridges, and have been abrasive to too many people. When Warren Buffett gave the eulogy for Coca-Cola CEO Don Keough, he summarized it in three or four words — “Everybody loved him.” I thought that was beautiful.

People will not say that about me, but I can control the decisions I make regarding my children. Will my kids feel that way about me?

I experienced something very salient and memorable involving my grandfather, who raised me. I grew up in Coney Island, Brooklyn — my mother, grandparents, and I shared a two-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment. We were very poor. My grandfather wasn’t my biological grandfather; he was my grandmother’s second husband, but he treated me like his son. He delivered the Daily News at night and was the most important man in my life.

He passed away the month before September 11th. At his funeral, his biological son was present. During the Jewish ceremony, when family members put dirt on the grave, his biological son approached with such animus. It was like “good riddance” — he took the shovel, threw dirt on the grave, and walked away. That sound still echoes with me.

I’ve always loved this quote from Carl Jacobi, the 18th-century mathematician: “Invert, always invert” — flip it on its head. My father wasn’t present in my life, so I became the father and husband he wasn’t. But watching that funeral moment, I resolved that would never happen to me. I never want my kids to feel that animus and animosity, wanting to dump dirt on my grave and walk away saying “good riddance."

The most important thing to me is what Adam Smith wrote about — not just the invisible hand, but the idea of being lovely and being loved. That second part, being loved, is scarce and valuable.

Scott Galloway recently gave a rant — I believe it was on Piers Morgan — where he talked about our obsession with Elon, innovation, and money while ignoring people who are hurting and suffering, including those losing USAID funding. He asked what it means to be a man. In his view, it wasn’t toxic masculinity — being a man means being able to take care of people.

We’ve lost that. There aren’t great male role models in public life today that young people celebrate for being good men through self-sacrifice. Everything centers on self-aggrandizement.

Regarding how to encourage or discourage people on certain paths: I want my kids to be truly happy. I ultimately don’t care where they go to college — the world has changed significantly. I don’t care what they do professionally. I want them to find purpose and meaning.

This relates to something interesting. Dan Senor works at Elliott Associates but is very active in Jewish and Israeli life. We attended Shabbat dinner at his house. I’m not religious — I’m an atheist but a tribal Jew. He blesses his children, and what struck me was that the blessing wasn’t about success, money, or career achievement. The blessing was “I want you to have a life full of meaning and purpose."

I thought that was beautiful. That’s what I want for my kids.

Philanthropy, Parenting, Short Videos

Jordan Schneider: We have five minutes for five quick questions. Take your pick — future of media advice for China Talk, New York mayoral race hot takes, what you’d do with a $10 billion philanthropic foundation, or something else.

Josh Wolfe: I don’t know.

Jordan Schneider: Where do you want to go?

Josh Wolfe: Mayoral race. I really hope Cuomo wins.

On advice for ChinaTalk, people get the audiences they deserve, and you have a smart, sophisticated, engaged audience looking for signal among the noise. Keep doing what you’re doing — your combination of Substack, podcasts, video content, periodic pieces, and great guests works well. I feel privileged to be here with you and enjoy reading your work.

Just maintain it because it’s a high-signal, no-BS voice. These things aren’t linear — there are step-change functions where suddenly something goes viral and you gain another thousand or ten thousand subscribers.

You should periodically write op-eds in major publications like the Wall Street Journal or Financial Times, sharing insights from your work. There are proxies like Stratfor and others in popular geopolitics, but you own a valuable niche. Over time, whether you do it or someone else does, there will likely be aggregation and acquisition — a China expert, Africa expert, defense expert — building a new media ecosystem where you could benefit from that outcome.

Jordan Schneider: Second and third questions — you’re pretty wealthy and likely to become wealthier. How do you think about big philanthropic investments beyond what you’re doing today?

Josh Wolfe: There are two aspects I really admire. Take what Bill Conway did — he’s not pursuing vainglorious naming opportunities. He literally identified deficits. His late wife was focused on nursing, so they fund nursing schools and programs because we have absolute scarcity there.

Considering the arc of AI, I believe in abundance and scarcity dynamics. What’s abundant will be machines helping with intellectual tasks — white-collar jobs will be hit while blue-collar jobs will surprisingly be safer than people think. The care aspect of healthcare will be critical.

If you ask what I want my kids doing: I grew up playing extensive video games and watching tons of TV, and I allow them that — not Monday through Thursday, but weekends they can play games, watch TV, engage in pop culture, watch sophisticated content like Fareed Zakaria and Jeopardy.

But I want them fully versed in AI. My 9-year-old is better than my wife at ChatGPT queries and Midjourney prompts for images. It’s creative expression.

Jordan Schneider: That’s a great age for it, right?

Josh Wolfe: Absolutely. My oldest daughter had to do an evolution project in seventh grade by hand — organisms with sharp teeth survive candy rain while weak-toothed ones die. She drew it manually. My current seventh-grader in that same class is using one of our companies, RunwayML, for AI video generation, creating full videos of different organisms in her scenario.

I want them totally versed in AI because ultimately — and you discussed this recently, maybe with Wang — the power isn’t in who has the chips, but who’s using them. Similarly, power isn’t in who has the applications, but who’s using them.

There’s a significant push for the world to use US-driven open-source or closed models rather than China-driven models that approach an asymptote of truth but never discuss Tiananmen Square, Xinjiang, or Uyghurs. We want the Global South influenced by American ideals of truth, Popperian hypothesis, conjecture, and criticism rather than Chinese systems.

But I want my kids using all these tools and understanding them. What will be scarce against all that abundance is human connection. They need to understand people, make eye contact — you’d be amazed how many kids, because of screens, have awkward, almost autistic interactions.

Being able to connect with people, understand them, read Shakespeare — that’s timeless. People change, costumes change, stages change, but human nature hasn’t changed since the Pleistocene African savannah.

That’s what I’d fund philanthropically. Derek mentioned CBT programs for young people earlier. I started a charter school 17 years ago in my native Coney Island, Brooklyn. We began with 90 fifth-graders in the projects. Now we have 1,000 scholars, 200-plus faculty, 100% college acceptance rate for first-generation college students. Eighty percent of families qualify for free and reduced lunch — a euphemism meaning a family of four makes less than $30,000, which is insane.

These families lost the ovarian lottery — the classic John Rawlsian veil of ignorance. These kids are no less intelligent than those born in Greenwich, Connecticut. But there’s no Army recruiting station on Greenwich’s Main Street — there is one on Cropsey and Stillwell in Coney Island. That’s not fair.

Those are worthy targets for philanthropic dollars.

Jordan Schneider: Okay, but let’s start from a $10 billion bucket. What are we talking about here?

Josh Wolfe: Where would I give? I would fund universal CBT for everybody in the country. I don’t know that it needs that much money — it just needs celebration in the country that helps people become more emotionally regulated and be their best version of themselves. It will reduce problems in our criminal justice system. It’ll reduce problems in corporate America. It’ll reduce a lot of problems across the board.

Jordan Schneider: Not to rag on you too much — you give very sophisticated answers to how to invest in the future of science and technology. That was a fine answer. But a lot of people, at a certain point in their life, switch from the sort of answers we discussed in the first 80 minutes to the question I just asked you. I’m curious: do you see the future differently when it comes to philanthropy?

Josh Wolfe: Where we give philanthropically right now reflects things that we prioritize. For me, complexity science through the Santa Fe Institute — brilliant people. I love it. I believe that’s a source of tremendous value. I’ve been part of that for 10 years as a trustee and believe deeply in it.

The charter school movement — I believe deeply in that because it’s a form of civil rights for people. My mom was a public school teacher, so this hits close to home.

Jordan Schneider: Let me try one more time. This is more of a meta question. The sort of investigation that you need to understand how to use philanthropic dollars efficiently and effectively — I’m curious how similar or different you think that is from investing?

Josh Wolfe: The only similarity is finding an amazing social entrepreneur. It’s like when we started the charter school — we basically backed this guy Jacob Newkin, who was starting the school. It’s the same thing. I used to talk publicly about Jacob: he’s the greatest social entrepreneur that I’ve backed by spending my time and money with him.

But we weren’t doing analysis on the market and the unmet need and that kind of thing. It tends to be something personal. For my wife, it’s the Center for Reproductive Rights. She’s on the board there, making sure that women have access to contraception and abortion and autonomy over their bodies. That’s a really important thing to her.

She’s not doing an analysis of where’s the best place to give or whether we should give more. It’s just: Roe v. Wade got overturned. There are women who are going to die in certain states because they can’t get abortions. What can we do about that? She gives a lot of money.

Jordan Schneider: Maybe we’ll close on this topic. If we’re entering a world where science receives less funding — Danny Crichton, who works for Lux Capital, wrote a really interesting piece about this — when the total amount of science that the US funds decreases, there’ll be a little spillover to China and the EU, but we’ll just have less science overall. Beyond CBT, what encouraging developments do you see for science and technology’s future? What basic research do you think people should be funding — the stuff that’s too risky for any venture capitalist to invest in?

Josh Wolfe: This might be controversial, but people should be spending far less money on climate philanthropy. The answer lies in what I call elemental energy and nuclear power. All that money should be redirected toward early-stage science and psychological and behavioral health research, because that will make society better.

The Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, Ford Foundation — these organizations were captured by the climate movement over the past 15 years. Honestly, I don’t know what it’s accomplished. It’s been a colossal waste of money.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking to the culture issue you raised earlier — it’s striking to me. I worked at an organization that was half nonprofit, half research fund, focusing on China and climate. On the climate side, they could get money to fund literally anything.

Josh Wolfe: It’s popular and makes you feel good. You go to a cocktail party and say, “Oh, I’m funding climate research.” Great, you’re doing wonderful work — Al Gore would be really proud. But the money is misplaced.

Jordan Schneider: It’s almost downstream of the culture. Who are the funders and trustees, and what’s popular with them? They’re not scientists conducting expected value calculations on human flourishing or whatever. Not to disparage anyone, but it’s something that resonates with them personally.

Josh Wolfe: Look, Sam Bankman-Fried was the emblematic figure of this, but the effective altruism movement was rational in trying to determine where we can do the most good. They approached it economically, looking at low-probability, high-magnitude events and identifying opportunities where small amounts of money could have significant leverage.

Going back to Conway’s nursing initiative — that’s not popular. People don’t get excited about addressing the massive nursing shortage. But he identified this as crucial, and they’re putting several billion dollars behind it. That’s noble work.

Bloomberg’s urban initiatives and charter school funding are excellent. People funding the arts because of personal passion — that’s great too. But we have massive problems with criminal justice reform and behavioral health domestically.

I’m not talking about everyone needing mental health days, but implementing cognitive behavioral therapy in schools at a young age. Before children’s prefrontal cortex develops at 25, we could help them develop better self-regulation. The world would be a much better place.

It would be tremendous to see philanthropists return to funding institutions like the old Cavendish Laboratory — putting billions of dollars into institutes that enable knowledge discovery.

Jordan Schneider: Rockefeller University — that’s incredible work. People need to get with the program.

Josh Wolfe: Carnegie Mellon, exactly. These institutions started with robber barons who decided to redirect money into academic institutions. This will happen again.

If you examine philanthropic funding historically, it began with private individuals, then government labs like Los Alamos, followed by Bell Labs (born from monopoly), then IBM Research. IBM centralized initially, then distributed with locations in Zurich and Almaden. Then came Google, Intel, and Microsoft Research.

Some of these corporate labs are under pressure now because they haven’t yielded significant results. But we’ll see the rise of private labs. You can see this already with the ARC Institute.

Jordan Schneider: Absolutely.

Josh Wolfe: The Collison brothers are major supporters there. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative represents major scientific initiatives comparable to Howard Hughes — himself a former defense contractor who invested enormous amounts into what became the Janelia campus, now one of the great sources of Nobel Prize winners.

Jordan Schneider: That’s a nice place to close. 50% of Howard Hughes researchers came to the US on visas! Joshua, thanks so much for being part of this.

Josh Wolfe: Great to be with you, man.

Jordan Schneider: Awesome. We’ll do this again in 10 years, and then you’ll be saying, “Here’s this philanthropic vision — look at all these molecules I found."

Josh Wolfe: I believe mostly in free enterprise, science, and technology. Early-stage ventures will handle a lot of that, but not the basic science research. There’s no market for that.

Bonus Riffs on Books

Cool. What are you reading? Anything good? Binge-watching anything inspiring or fun?

Jordan Schneider: Two books. I’m a new parent — I have a 10-month-old at home.

Josh Wolfe: Boy or girl?

Jordan Schneider: Girl. First child.

Josh Wolfe: Wow.

Jordan Schneider: I read all these books on paternity leave about “How I Raised My Child in X Country.” They were not good. But one was excellent: Italian Education. It’s by a cranky British guy who married an Italian woman and raised his kids in late 1980s-90s Verona. All these other books are basically backhanded critiques of American parents from whatever direction. But he’s just observing this really interesting, weird society where you have very tight connections between parents and kids — for better and worse, from my perspective, across many dimensions.

It was engaging, funny, smart, with nice vignettes. Each chapter stands on its own, which is good for 3 AM reading.

Book number two — A Social History of the Machine Gun by John Ellis.

The book tells the story of the machine gun through different lenses. He’s a military historian who wrote about World War I and World War II tactics. But in this book, he explored the technological evolution from the Maxim gun all the way through World War II — who invented it, why, and where it came from.

There’s a fascinating acquisition story too, because people didn’t think it was real and didn’t want to buy it. There were prototypes but no factory yet, so you had these hucksters trying to —

Josh Wolfe: What years was this?

Jordan Schneider: At the start of World War I, the British had one gun for every 2,000 people. You had to get to 1916-1917 for them to actually be making and buying enough machine guns.

Josh Wolfe: That’s amazing.

Jordan Schneider: It took an enormous amount of time. The technology was already there in the 1880s and 1890s. There were examples from wars in different countries — the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, the Crimean War. You could see it if you were looking at the right things.

Ellis gives examples of smart colonels saying, “Guys, we need to buy these guns — they’re a big deal.” But people said no, and they all said no way too late.

The other story he tells is about the psychology of not just the people buying the guns, but the officers themselves who had to abandon their mindset about what made a successful officer. Being a sharpshooter wasn’t considered honorable. What won wars throughout the 19th century was discipline, standing in line without fear, marching together to bring maximum power. That’s what the technological paradigm demanded — willingness to maintain rank.

It took over 100 years for people to change their mindsets and understand that you actually need to be distributed, use natural cover on the ground, and get away from the Napoleonic mindset of gallant charges. Those charges were the correct evolutionary answer in a different time period, but not by the US Civil War, definitely not by the end of the 19th century, and absolutely not by World War I.

Josh Wolfe: It’s interesting — the juxtaposition of the two books. One is arguably about technology of life (all parenting is a form of life technology), and the other is about technology of death. It’s a nice contrast in what you’re reading.

Quick parenting observations — First, if you walk into a bookstore like Barnes & Noble — which really don’t exist anymore —

Jordan Schneider: There’s one three blocks away!

Josh Wolfe: The mere existence of a handful doesn’t change that they’ve largely disappeared. There used to be 20 in New York City; now there are one, two, or three.

My point is, when you go into any section — investing, relationships, or parenting — and see 200 books, it means nobody has any idea what they’re doing. If they did, there would be one book with all the answers.

What I learned, especially with our first child, is that you develop a whole bunch of lessons, then you have a second child and they’re all wrong. Once you have more than one child, the nature versus nurture debate is settled. They are genetically different from day one — their predispositions, attitudes, sleep patterns, crying patterns, wants and needs. Their personalities persist from birth. The one who’s more reactive, the one who’s more smiley — it’s absolutely fascinating.

Second point on parenting, which relates to China — when I was growing up, my mother said, “You need to learn golf and Japanese because that’s the lingua franca of business in the ’80s.” Then it became, “You need to learn Mandarin and coding because that’s the lingua franca."

Neither of those things really matter today. The pace of AI development means coding can now be done by AI agents. Computer scientists who thought they were in a valued position are suddenly thinking, “Oh my God, I’m being replaced by agents."

Translation is pretty incredible now too. I don’t know what the next parental trope will be, but it’s usually wrong.

Jordan Schneider: We can take it back to the machine guns, right? What was successful for you as you were coming up in the world and in the institutions that shaped you isn’t necessarily going to be the thing for the next era. The humility to understand that — both from a defense acquisitions perspective and a parenting perspective — is really hard.

Josh Wolfe: I’ll give you an investing version of that. First, the most dangerous words everyone always says are “this time is different” — because it never is. If you know Shakespeare, then of course it’s never different. Human nature is constant.

But when parents utter certain words, it’s predictive — similar to the defense acquisitions issue or for investing. Want to know what will be the next $10 billion industry? Here it is: “It will rot your brain.” Every time a parent says “it will rot your brain” about something they don’t want their kids doing, that thing becomes the next massive industry.

Rock and roll in the ’50s, TV in the ’60s and ’70s, chat rooms in the ’80s and ’90s, video games in the ’90s and 2000s — every one of those things that was the target of parental ire became the next $10 billion industry. Tipper Gore with parental advisory lyrics and rap music — rap became the biggest genre of music in the following decade.

Just listen to what parents are terrified about right now. The gamers became our modern robotic surgeons and drone pilots. Whatever they’re freaking out about now — maybe TikTok (though I have problems with that for different reasons) — it could be movie-making on social media or whatever.

Josh tries to defend short video

Jordan Schneider: This is the hardest question of the day — give me the optimistic short video take.

Josh Wolfe: We’ve democratized the ability to have creative expression with special effects that used to cost $50 million. Filmmakers used to be siloed in studios with hierarchies, casting couches, and Harvey Weinsteins — awful people. Now there’s freedom of expression where people can create tragedy, drama, comedy, and surrealist content with these tools at their fingertips.

My 9- and 12-year-olds are better filmmakers than I was at 25. They have tools today that Hollywood executives used for Terminator or The Abyss — remember James Cameron’s special effects that seemed amazing back then? That’s from a creator perspective.

Jordan Schneider: What about from a consumption perspective? Having culture delivered in 30-second chunks?

Josh Wolfe: Again, look at it from abundance and scarcity perspectives. I 100% agree that if you’re constantly being trained for short attention spans, that’s problematic. We literally practice patience as a family because I know there are so many competing things offering fast dopamine hits and quick responses. We do long periods of quiet reading from physical books as a family. We watch long movies instead of 30-minute segments.

Jordan Schneider: No, but you’re telling me the things parents are scared of are actually going to be the future. What’s positive about consuming content in 30 seconds?

Josh Wolfe: I’d argue that your ability to process multimodal information is far better. Look at the average older person right now — they’re focused on one thing, they’re slow. You’re probably able to switch between a WhatsApp chat group, Twitter, watching a short video, and checking emails. Your ability to multitask while retaining the ability to function is super valuable.

Jordan Schneider: Your heart’s not in this one…

Josh Wolfe: It’s okay, but here’s what I know: it’s not as bad as people think. The TikTok stuff is concerning, but short-form video generally isn’t bad.

Jordan Schneider: Okay.

Josh Wolfe: I’m optimistic on the science and technology piece. I’ll still be skeptical about the human nature piece, but optimistic about science and technology.

Jordan Schneider: All right, let’s call it there then. This was really fun. Do you have a book to shout out?

Josh Wolfe: Let’s close on fiction and nonfiction. For nonfiction: The biggest debate my wife and I have had was over a book by Robert Sapolsky, a Stanford primatologist and neuroscientist who’s written a series of books. His first one was Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers: The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping. The punchline was that zebras run for their lives in their ancestral environment, then they’re calm. We have constant stressors all day long that didn’t exist in our ancestral environment.

But his more recent book is called Determined. Either you’ll want to throw it across the room, or you’ll want to send copies to everybody. It depends on whether you agree — as I do — that we do not have free will, or disagree — as my wife does — that we are filled with agency and of course have free will.

Danny Kahneman was a friend. His belief before he died was that neither free will nor consciousness exist — that they are both useful illusions. I very much subscribe to that view.

For fiction, Amor Towles has a short story collection called Table for Two. He wrote Rules of Civility, which is great. There’s a character from the second half of that book who gets extended treatment in a few more chapters in this collection.

But there’s one story that deeply touched me called “The Bootlegger.” It’s a short story that takes place in New York. The beauty of this, for me personally, was that I happened to post on Twitter about my love for this particular story. Amor Towles replies, which was very meaningful, and he says, “This is probably the most autobiographical story I ever wrote."

It’s a relatively short story set here in New York. A young couple, something happens, they go to Carnegie Hall, and this story unfolds. There’s a particular classical musician referenced in this fictional piece, and he replies to the story because he’s actually in it. It was this surreal fictional story that was a slight roman à clef of Towles’s life. He replies to me on Twitter, then the classical musician does too. I was like, “This is amazing."

Jordan Schneider: That’s really fun.

Josh Wolfe: I highly recommend Table for Two by Amor Towles. It’s a set of vignettes around two characters — probably 10 or 12 short stories. But “The Bootlegger” is awesome.

Jordan Schneider: Thanks so much.

Josh Wolfe: Great to be with you.

As Josh says, keep up the great content (and this was an insightful interview as always)!

Loved the shoutout to “Overcomplicated” - that book is great.