From Yan'an to Mar-a-Lago

Orville Schell on MAGA-Mao Echoes

Can studying Mao Zedong help explain Donald Trump?

To find out, ChinaTalk interviewed the legendary sinologist Orville Schell, who visited China during the Cultural Revolution and is currently at the Asia Society.

We discuss…

Mao Zedong’s psychology and political style,

Similarities and differences between Mao and Trump,

How Mao-era traumas reverberate in modern China, including how the Cultural Revolution has influenced the Xi family,

How Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping survived the Cultural Revolution, and which of their tactics could be useful in modern America,

What civil society can do to defend democracy over the next four years.

Co-hosting is Alexander Boyd, associate editor at China Books Review and former ChinaTalk intern.

Listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

Culture War x Cultural Revolution

Alexander Boyd: Orville, you wrote the most prominent essay on Trump’s Cultural Revolution, comparing Donald Trump’s behavior in office and personal style to Mao Zedong. To start, what is Maoism, and how would you describe Mao Zedong?

Orville Schell: Mao Zedong, of course, was the great progenitor of the Chinese Communist Revolution. He was a Marxist-Leninist, and he liked control as any autocrat would. However, one of the hallmarks of Mao Zedong was also an abiding interest in throwing things off balance as a way to gain even greater power.

In this regard, he became a great fan of Sun Wukong. This golden-haired monkey was one of the heroes of the classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West, which tells the story of Buddhist scriptures being brought from India to China. One of the most prominent features of this monkey king was his love of disorder. His sort of watchword was “dànào-tiāngōng” (大鬧天宮), to make great disorder under heaven. Mao Zedong actually ended one of his poems with that line, and he always loved this novel, Journey to the West.

When the Cultural Revolution arrived, I think this was a real consummate expression of Mao’s affection for chaos. He did feel that not only did Chinese society need to be upturned, but the whole political structure of China needed to be upturned. Everything in effect needed to be “fānshēn" (翻身), as he said, “turned over.” He adopted many expressions similar to the Monkey King that expressed his love of contradiction and disorder. Class struggle, of course, which became the hallmark of the Cultural Revolution, was a form of deep and disturbing disorder.

Alexander Boyd: Where did Mao’s need for constant chaos and rebellion come from? In your Project Syndicate essay, you posit that it came from his troubled relationship with his father. Can you describe the parallels to the case of Donald Trump, who had a famously domineering father himself?

Orville Schell: The one place where we really get chapter and verse on Mao’s relationship to his father growing up in Hunan at the end of the 19th century was in Red Star over China by Edgar Snow. Mao told Snow that he had a very adversarial relationship with his father. He even said he hated his father, that his father was a tyrant, and they were constantly battling. On a number of occasions, Mao Zedong actually ran away from his home.

He did have a very sort of Buddhist-inclined, loving mother who made a lot of difference. But the relationship with his father clearly set off the notion of the world as an adversarial place. He tells Snow that he learned only by standing up to his father could he survive, and then his father would come to heel in some sense and not just overwhelm him with his sort of tyrannical paternal role.

That sort of characterizes Mao, and in fact Trump too, as we learn from his niece (the daughter of his older brother), who is a psychologist. Trump had a father who was very preemptive, very tyrannical and very judgmental.

Wallowing off into the bog of psychobabble here, any human being who reads literature knows that a father’s relationship to his son and vice versa is a profoundly influential relationship. As a young man grows up, that relationship forms him.

Alexander Boyd: We know that Mao loved to speak in allegory. He often would speak about one thing but mean another. How much can we believe his stories to Edgar Snow? And is it just a metaphor for American paternalism?

Orville Schell: I think at the period when Edgar Snow was doing these interviews with Mao was in the 1930s. We hadn’t started all the rectification movements and Mao had not been in power with all his mass campaigns. He had just arrived in Shaanxi province. I think that we get a pretty unalloyed representation of his early years. I don’t see there’d be any reason for him to be setting traps or deceiving Snow.

Throughout his life, Mao easily took umbrage at things when he felt sat upon or disrespected. Another famous example, of course, is when he finally went to Beijing in the late 1920s and he became a senior intern of some sort at the Library in Beijing University. He used to feel incredibly disdained by Chinese intellectuals who’d come in and sneer at his hickey Hunan accent.

If you‘ve ever heard Mao Zedong speak or seen a film in which he speaks, he’s almost unintelligible to Mandarin speakers. Like most Chinese people of his generation, including Deng Xiaoping and Chiang Kai Shek, he preferred to speak his local dialect.

This laid the track for Mao’s antipathy towards intellectuals, just like Trump hates intellectuals and universities. He thinks they’re arrogant, they’re elitist, they look down on people like him and down on working people, et cetera. Mao felt very much that no matter what he did in his formative years, he was disdained and disrespected by the intellectual class.

Of course, in that sense, I think he is a metaphor for sort of the whole ‘kultur’ of China in a sense that it is aggrieved, it’s been humiliated, it has been looked down on, kicked around, exploited, you name it.

Alexander Boyd: Another similarity between Trump and Mao is that both men had a lot of wives, often tumultuous ends to those relationships with women, and a propensity to start new relationships before the last one ended.

Yet another parallel is Mao’s exposure to Hunan secret societies, specifically Gēlǎohuì (哥老會), the Red Gang, and his time as an organizer at Anyuan. This mimics Trump’s early mob ties, especially in the New York of John Gotti and then Rudy Giuliani, who was a big mob fighter back in his day.

Their styles of governance are also similar — Mao made frequent trips outside of Beijing, and he loved to launch campaigns while on the move, much like Trump’s Mar-a-Lago golf club trips.

Are these comparisons substantial, or is it just the case that when you have so much information about two people, you can always draw connections between them?

Orville Schell: It’s true that both Mao and Trump had a lot of wives and a lot of ladies. What that suggests is that they need to have that kind of affirmation and signs that they can beguile people and win people over, which speaks to me of a fundamental lack of self-confidence. Both of them derived a certain measure of prowess from their ability to attract beautiful women.

Trump still talks about women as objects and as adornments. Mao clearly was the same. There were other leaders in China who were not. Chiang Kai-shek had a lot of ladies (and ladies of the night as well in his youth), but after he got married, he was quite faithful. I don’t quite know what to make of Zhou Enlai, but he had one wife. Whether he was gay or not, it’s a question people do care about.

Mao was somewhat special, and he arrogated that special right to poach on women himself. But when revolution came home to roost after 1949, it was not something he found acceptable in ordinary people or even in his acolytes. He was very puritan. But he was not just like Trump. Trump purports to be a Christian and yet doesn’t abide in any meaningful way by the notion of loyalty implicit in marriage.

Jordan Schneider: Shall we discuss the deep state example?

Alexander Boyd: Trump famously vowed to drain the swamp and railed against a deep state that he perceives as having both frustrated his attempts to exercise power in his first term and prevented him from regaining office in 2020. Now he’s engaged in a campaign of revenge against all those purported deep state agents.

Many people, and you chief among them, have made that comparison to the Cultural Revolution where a frustrated and suspicious Mao unleashed these animal forces within China to take down a party in a state leadership that he felt was shackling his own ambitions to remake China. Is that an accurate comparison in your mind?

Orville Schell: One of the hallmarks of Mao’s revolution was a sense that somehow the party (which he himself had helped build) and the state (which was the handmaiden of the party) were ultimately the refuge of rivals.

He had a great antipathy against bureaucratism. This also speaks of his love of disorder as a creative force. When he started the Cultural Revolution, one of the first things he did was to issue a wall poster that said “bombard the headquarters” (pào dǎ sīlìngbù, 炮打司令部). What he meant by that was that he felt the party had become ossified. It had become the refuge of bureaucrats who were living high on the hog but didn‘t want to make revolution anymore and found class warfare too disruptive.

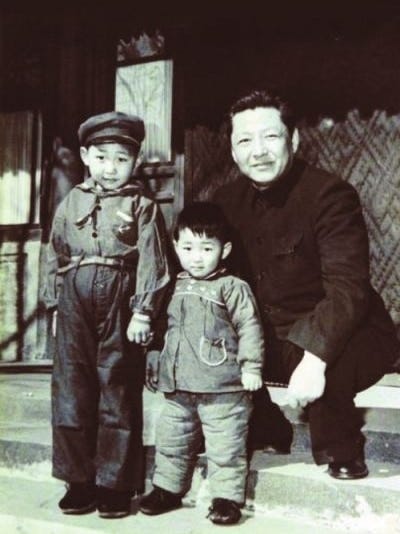

He felt that it was time to destroy it. How did he do that? He gave permission to young people, idealistic young people, to attack. Almost all of the leaders who were potential adversaries of Mao either died or were purged. Xi Jinping’s father was one of them, a vice premier who had a very bitter purging.

In that regard, Mao Zedong took, I think, great satisfaction in overturning even his close revolutionary comrades. Here Trump is not too dissimilar. He seems to be invigorated by the idea of destroying institutions that he views as refuges of people who might be against him and of firing people he’s hired, turning against people who he perceives as potential rivals. He demands complete fealty and loyalty or you’re in trouble.

Here too, I think there’s a kind of a similarity in the way the two relate to other leaders and to institutions of government, the deep state. It’s the equivalent for Trump of what the party and the state that he himself helped build were in China. He saw them as slowing down his revolution, as harboring his adversaries and as being overly bureaucratic, what he called “sugar-coated bullets of the bourgeoisie” (资产阶级的糖衣炮弹). In other words, they’d given up their revolutionary vigor in favor of staid bureaucratic forms of government.

Alexander Boyd: So if there’s an attack on the bureaucracy, does that make Elon Musk and DOGE a new Kuai Dafu 蒯大富 and the Red Guards?

Orville Schell: Musk is older. Kuai Dafu was one of the earliest Red Guard leaders at Tsinghua University when Mao issued his order to bombard the headquarters.

Elon Musk should know better, but I think he too has a kind of innate impulse that chaos is a creative element. It’s one step away from the Silicon Valley mantra, “failure is positive.” But I think he does share with Trump this idea that somehow you need to clean out the Augean stables of the government. I don’t know why Musk might feel disrespected or disdained when he’s been so successful and the richest man in the world.

Here, too, I think we have to remember that these leaders are human beings. They’re not just rational creatures who look at the national interest of the country or read reports to make rational decisions. Some leaders are completely crazy. We know from Euripides and Shakespeare that leaders are completely crazy and they do astounding things.

You can read Stephen Greenblatt’s book, Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics, which is about six great plays that Shakespeare wrote about tyrannical leaders. There’s nothing new here. It’s just that policy people and I think many academics are loath to recognize that we’re also dealing with something very human here, namely, leaders with deep and tragic flaws, which in Euripides are hubris, arrogance, and overreach.

When Croesus — we‘ve derived the expression “rich as Croesus” — went to the oracle of Delphi, he governed the state of Lydia, about whether he should go to war. He got the diction back from the oracle that if he went to war, he’d lose his kingdom. What did he do? He went to war and lost his kingdom.

There’s a little of that going on here. I think we need to factor the human dimension into the equation of understanding big leaders like Putin, Orban, Xi Jinping and others. Look back at their formative years.

Here, I highly recommend a wonderful new book that’s coming out by Joseph Torigan on Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋. You see what nightmarish experience Xi Jinping went through as the son of a man who was twice purged during Xi Jinping’s teenage years, and was purged the second time as a counter-historical, counter-revolutionary. And what travails Xi Jinping as a young man went through to have a father who was in the five black categories.

This is a little bit beyond the mandate of so-called China socialist. But I do think that here’s where literature, drama, some of these other representations of leadership help us understand what’s going on.

Alexander Boyd: Let’s stay on Xi Jinping here for a second and Xi Zhongxun as well. What is Xi Jinping’s view on the Cultural Revolution today? Obviously it’s opaque, but I agree Torigan’s book is incredible and I read his section on Xi Jinping’s Cultural Revolution.

Orville Schell: I think it’s unfair to say that Xi Jinping is like Trump. Xi Jinping does not like disorder. He does not want to create great disorder under heaven, unlike Mao. The part of Mao he does bond with and did grow up with and appreciate is the Leninist part — the organized state, organized party control, autocracy. But he has no fascination for the part which we’ve been talking about.

This is why I suggested if Xi Jinping wants to come to some better understanding of who Trump is, ironically he has a homegrown example in Mao Zedong. He lived through it. He knows what people like that can do to a society and to even the global order. I think maybe he has thought this way. I don’t know, but I think he uniquely, unlike many Americans who’ve never been through this kind of disturbance, shouldn’t be so surprised by Trump.

Why do we think as Americans, when Italy had Mussolini and Germany had Hitler and Russia had Stalin and Spain had Franco, Salazar in Portugal and on and on, why do we think that we are somehow immune from these kinds of aberrant, overreaching, arrogant, and finally incredibly destructive leaders?

Jordan Schneider: China from 1949-1967 was a very different place with a very different governance system than America circa 2016 or 2025. Shall we discuss some of the differences here?

Alexander Boyd: Well, I think the first place that we should start is rise to power. Trump, you know, for better or for worse, won two elections, and Mao won power through civil war and various other means. Orville, what would you say is the biggest difference between Trump and Mao?

Orville Schell: Trump is more like Hitler, who came to power by being elected Chancellor of the Reichstag, whereas, as you point out, Mao Zedong came to power through insurgency and civil war.

Obviously, you can‘t completely compare these people, but I think in trying to understand the leaders of the present, it does behoove us to look back at leaders in the past who also created disorder, one kind or another — a world war, economic crisis, a revolution, whatever. That might help us understand a little bit what it is they’re offended by. What do they want? What would propitiate them? How do you deal with them? Can you deal with them?

I don‘t mean to compare Xi Jinping with Trump. But only to say that China’s historical experience of having undergone probably the most tectonic, catastrophic, and destructive revolution in history might help Xi understand what animates a leader like Trump and how best to deal with it.

Jordan Schneider: How best to deal with Mao is kind of not something people really figured out. Can you talk about what the antibodies were over the course of his reign, and highlight some examples of successful and unsuccessful pushback against his craziest ideas?

Orville Schell: Well, of course, the best, the biggest antibody of all to Mao was death. Many autocrats are very disruptive. Hitler died in his bunker, Stalin died, and wildly began to change. I don’t know what the antidote to Mao at that period would be, but I will say this, that if we look at our own country, there is a hint of similarity among the way people come to heel when big leader culture gets rolling.

The Republican Party is completely supine now. We do have the Democratic Party still raging against the storm. But one of the lessons I think that is quite striking about the Chinese communist revolutionary period was the way in which everybody finally was neutered. Those few who did speak out, and there were some, had very bitter ends. All know what happened. This is another hallmark of powerful and effective autocratic leaders is that they manage by one way or another — and one way is disorder — to intimidate people, frighten people into submission and silence.

Alexander Boyd: I think in a lot of histories of the 1970s though, everyone points to 1971 and Lin Biao’s death.

Jordan Schneider: Why don’t we do the Great Leap Forward and response to that? Because Mao had to do with self-criticism, right? This was a real brushback moment for him where after killing eight figures of his own citizens, there did end up being some pushback from the top that forced him down a policy path he wasn’t really excited to take.

Orville Schell: After the Great Leap Forward, many leaders like Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai and Peng Dehuai felt it was too excessive. Forty million people dead, starvation, agriculture in ruins. They did for a brief period of time prevail. What was Mao’s answer?

Mao’s answer was the Socialist Education Campaign, which is a prelude to the Cultural Revolution, which ended up labeling people like Peng Dehuai at the Lushan conference, put out of business very quickly, ended up in jail. The president of China, Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, were sent down. In other words, almost all the leaders, veteran revolutionaries that had accompanied Mao in the Long March in the Yan’an period, ended up in the doghouse or dead.

That was China’s experience. That made it very difficult for any voices of dissent to find any purchase. I remember being there myself during the end of the Cultural Revolution and just thinking, well, this is the way it is. There were no voices. They wouldn’t even talk to you as a foreigner. Nobody had permission even to interact in a normal human way with anybody foreign or an outsider because they were afraid. Mao had brought complete submission down onto society.

That didn‘t mean he suffocated all of the impulses that had built up over previous decades — they remained latent and dormant and they arose again when Mao died.

Alexander Boyd: Basically the biggest argument against Trump’s effort to remake America in his image, to bring manufacturing onshore, is that Mao, with more power at his disposal, more party at his disposal, a whole society cowed, actually failed. Even more recent scholarship, like Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian’s new book The Great Transformation: China’s Road from Revolution to Reform argues that opening and reform really began in the 1970s. If Trump is Mao in this comparison, is the Trumpist effort, you know, this great “cultural revolution” in America, is it doomed to fail right from the beginning?

Orville Schell: Well, I think we could be doomed to something even worse. Mao failed in the Great Leap Forward. Then in order to regain and maintain power, he brought on the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. It’s hard to know. We can’t predict history and we don’t know whether American democracy will survive.

What we want to say is that we know this archetype of leader and whether it’s a communist, a Leninist, a so-called democrat, Nazi, fascist, whatever. That’s why I wrote some of these essays, to just remind people that there are examples throughout history and literature of these kinds of people. We need to better understand because now it’s America’s turn to have one.

Jordan Schneider: I think another one of the big differences that Tanner Greer pointed out on a show earlier where I tried to compare Trump to Hitler was the ideological commitment level that Trump has versus someone like a Mao or a Hitler who deeply believed in his bones in class struggle or Lebensraum or international Jewish conspiracy. Yes, Trump’s got some views on trade policy, but he lifted them after the bond market changed. It’s the sort of the level of focus which he can bring or has shown, the level of focus that he’s shown he can bring to policy stuff versus some of the other sort of totalitarians that you reference who maybe have some personality traits in common, but also kind of have a real agenda behind them. Whereas our current president, not so much.

Orville Schell: I agree with that, Jordan. Mao had a very highly evolved ideological agenda and analysis of how the world worked, where history was going, knowing what the dynamics would be. They did hew to that in various ways, sometimes rather opportunistically or in a utilitarian fashion. That’s communism.

But fascism is a very different animal. If you read Robert Paxton’s book on fascism, you begin to understand people like Mussolini. He had no ideology. He was sort of inventing himself as he went along. I think that’s one of the big differences between Trump and Mao. Mao was a very intelligent man and actually a good writer, good poet. He thought.

I don’t think Trump thinks — he acts almost like an animal. He feels this today and he acts, he responds. He certainly has no ideology or no sort of political commitments to principles that guide him in what he does. It’s more what he feels like doing. He feels someone doesn’t like him. He feels threatened. Whatever. It’s almost animal-like in his responses, which are completely irrational.

Alexander Boyd: This is actually not so much a continuation of this question, but it’s a different tack. I’m curious about Mao’s foreign policy and Trump’s foreign policy. A curious similarity is that Mao stated, “I like rightists.” He met with Richard Nixon. He found them easy to deal with in general, perhaps because he understood the ideological motivations of, or he perceived himself to understand the ideological motivations of capitalist right-wing politicians.

Then, Trump himself meeting today in the Oval Office with Carney, the Prime Minister of Canada, and earlier saying something like “I like the left” in reference to him not wanting Pierre Poilievre to win in Canada. Why do you think that Mao liked rightists or claimed to like rightists? What sort of insights does that give us into Trump’s foreign policy?

Orville Schell: In many ways, Mao could be a rightist, but I don’t think he liked anyone who opposed him. He viewed the right as opposing him and as opposing his ability to control thinking and ideas. This is why you get the whole idea of sīxiǎng gǎizào (思想改造), thought reform, that there’s a correct way to think and Mao helps limit that, describe that, lay the boundaries for that out. If you don’t want to think that way, then you’re a rightist or maybe even a leftist and then you deserve to be defenestrated.

I think Mao says he likes rightists because he thinks they’re practical and he can deal with them. It’s a bit of a capo-to-capo business. You can deal with a thug, even if you call him a rightist, but I don’t think he had any affection for rightists or leftists. These are categories of convenience into which he put people when he needed to get them off the stage.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, I feel like the capo-to-capo thing is it’s less him liking Mark Carney, which I just truly do not believe, and more the ease and excitement where he gets talking to big, powerful, authoritarian leaders, as opposed to democratically elected ones.

Orville Schell: I think that, Jordan, if I may say, when Nixon and Kissinger went to China in ’72 and ’71 to set it up, I think there was a certain thrill for Zhou Enlai and Mao to have these people come hat in hand to Beijing to talk to them. Because remember that even though they were opposed to imperialism, colonialism, capitalism, America, et cetera, there is, I think, in my experience, at least amongst Chinese leaders representing their country, a deep and abiding wish to be respected.

They speak about that all the time, mutual respect and understanding, as if to say, “Can’t you just respect us as a dictatorship? Show us some respect. We’ve got a good economy, we’ve done a lot of amazing things,” which is true. Again, autocrats, one of the things that really riles them is that they’re cast out, they’re disdained, not considered proper company for liberal democratic states.

When China is the aggrieved, humiliated, kicked-around sick man of Asia, they want nothing more than to be respected. That is a complete contradiction because if you don’t act respectably, it’s very hard to be respected. Yet that is something they deeply crave, even though they would never acknowledge it.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, I think it kind of works the other way as well, where you just see how big Trump’s smile was in his 2017 visit to China.

Orville Schell: I’ve been on several presidential trips, like for instance, with Clinton, which was completely different, very informal and open and cheerful. But Trump’s trip, it was all about pomp, circumstance, awe, ceremony and ritual. Both leaders were trying to impress each other and Xi Jinping wanted to impress Trump. You remember he took him to the Forbidden City and they had a banquet and all the rest of it.

But there were no moments of bonhomie, of personal smiling and back-slapping and saying, “Hey, we’ll work this out.” No, it was all about sort of who is the bigger dog with the most impressive marching band and most impressive Great Hall of the People. I think that’s very characteristic of both Trump and Xi. Trump wants to have a parade, just like Xi gets to have parades with a lot of tanks and missiles going by.

There’s an element of similarity, I think, of both deeply insecure men fundamentally, and nothing like a good parade to puff up insecure leaders’ egos.

Jordan Schneider: Can you talk about the sort of red versus expert dilemma, which we’re seeing play out with Laura Loomer in this administration?

Orville Schell: Remember that during the Cultural Revolution there were many, many struggles going on. One of them was the struggle between being Red and an expert. Experts, of course, were people who knew how to do something. They were the intellectuals, they were the scientists, the technicians, people who ran institutions and could be accused of bureaucracy.

The Reds were the people who wholeheartedly embraced Mao Zedong and were dedicated to overthrowing institutions of the experts. In that period, not only was expertise disdained and diminished in standing as a societal avocation, it was a hallmark of those first people being insubordinate. It was a different kind of loyalty — not to Mao, not to Maoism and Marxism-Leninism, but to rationalism, to scientific experiment, or these other things that had a kind of a logic that defied complete and total loyalty to the Great Helmsman, whatever he represented at the time.

Whether the party was intact or not during the Cultural Revolution, it was not loyalty to Mao and the revolution versus loyalty to whatever other thing you might be — a scientist, a businessman loyal to profit, and policymakers who are loyal to trying to figure out the national interest. That was a huge divide.

We see that now with Trump. What he wants is not people who know something in the FDA or the FAA. He wants people who are loyal. So you got Laura Loomer, like Kang Sheng or Chen Boda or someone running around firing people and putting people in prison for Mao.

Jordan Schneider: What was the upside for Mao of getting rid of the experts?

Orville Schell: Liu Binyan, the great writer of the 1980s, wrote a book called A Higher Kind of Loyalty. This was an analysis of people who felt a loyalty, whether it was through religion, technology, science, intellect, or just ideals, to something other than the revolution and the leader.

What Mao rejected and recoiled from was professionals who were experts, who said, “No, this revolution does not make sense economically, scientifically or in any other way. It’s mayhem.” That put them immediately on the enemies list. That’s why intellectuals, and they categorized them into many different categories, were pilloried because they couldn’t be totally loyal as religious people were, because religious people owe a different loyalty to their God and to their principles and to their morality, not to the leader.

Mao couldn’t stand that, so he waged war against those people. We see sort of, I think, hints of that happening now in America where people like Fauci in the first administration of Trump were not respected at all. He was a very good scientist, very devoted public servant. We see attacks on vaccines, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., science has proven measles vaccines work. We see a lot of things like this looming up again where what’s important is not logic, but it’s loyalty to the leader.

Alexander Boyd: But Mao also resented his need for these bureaucrats, for these technical experts. And chief among them was his own Confucius, Zhou Enlai. Even though he was fighting against these empiricists and scientists, cultural leaders and everything during the Cultural Revolution, probably the number one empiricist of all was right next to him. Although at the same time many Chinese spoke about him like we spoke about John Kelly in the first term. “Oh, he’ll be able to restrain Mao’s worst instincts.” How do you read Zhou Enlai?

Orville Schell: Zhou Enlai was a restraining influence. He was also a complete factotum. When you see what he was put through, like in the rectification campaign in 1942 where he sat before the Politburo for five days, wrote self-criticism, self-immolations, humiliating, pusillanimous kind. He paid a bitter price as a human being to keep in Mao’s good-enough graces. Still, Mao endlessly tormented him and humiliated him — very smart man. And he took it. Why? That’s an interesting question.

Did he think he was doing good like Matt Pottinger in the first administration of Trump, that if he just kept his head down and tried to do a good job, he could restrain the leader? But there was also probably a lust for power, an urge towards power which kept him there. He once got that needle in his arm, it was very hard to get out or he’d end up like his friend Liu Shaoqi — imprisoned or dead.

These kinds of leaders demand not one-time propitiation declarations of fealty and loyalty, but continuous. The leader keeps ramping up the ask. If the lieutenant wants to stay in their graces, they have to keep becoming more and more genuflective. We see an awful lot of people left the first administration of Trump and now he’s already lost all the people he’s lost. I mean, Rubio, everybody. He’s taken over positions of Waltz and others who drop like flies because it’s very difficult to satisfy the demands of autocrats who require 200% loyalty.

Alexander Boyd: Is part of this the “Coalitions of the Weak” thesis put out by Victor Shih about how Mao would often rehabilitate disgraced cadres? You saw that with Deng Xiaoping, you saw that with Zhou Enlai, he’d constantly send people down, bring them back, criticize them, humiliate them, purge them, restore them, and it ended up necessitating their loyalty. They created psychological dependence, but also political dependence.

Especially with Victor Shih, he’s talking about the Fourth Front Army in the Long March, I believe Zhang Guotao. Is that a similar coalition with Trump and Mao? And how did Mao’s coalition of the weak work? And is that an effective governance tool? We might be skeptical of it, but Rubio, who has no basis left in the GOP, has basically been entirely kneecapped, was humiliated in his run — he’s Zhou Enlai exactly. But he could also be our Deng Xiaoping.

Orville Schell: If you want some good reading, go back and read Deng Xiaoping’s self-criticism during the Cultural Revolution. He just abased himself and said over and over again, “I didn’t know Chairman Mao. I didn’t appreciate the brilliance of Chairman Mao.” Even he went through the ultimate humiliation but survived intact.

I was in Washington and went on the whole trip when Deng arrived in 1979 to normalize relationships. And you did get the sense of somebody who had his own sense of gravity about him, wasn’t a deeply insecure person just craving slavish loyalty. Deng Xiaoping was different. I would say Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 and Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 were also different. When you look through the different leaders, you want to get back and judge their character. Yes, times were different, but Deng Xiaoping was special because he had seniority. He did get cashiered twice, but he never lost his fundamental sense of himself, which I think many other people did.

Alexander Boyd: Let’s be optimistic here and say there’ll be a post-Trump GOP. How did those Chinese survivors like Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang, etc. make it through Mao’s Cultural Revolution? And what could that tell you for an aspiring politician today hoping to make it through Trump 2.0 and still have a political career?

Orville Schell: Xi Jinping made it through and he’s done alright. There’s no simple answer. In the good old days when you also had imperial autocracies in the form of emperors, if you ran afoul of the government, you could run up into the mountains and become a Buddhist monk or a Taoist priest, and mind your own business. But that wasn’t possible under Mao.

We’ll see about what happens in America. I suspect we won’t get to such a state in America, but who knows? The question is, during autocracy, authoritarian rule, what should good people do? If you stick your head up, it gets chopped off. You can run abroad, you’re just in waiting. There’s not much you can do. It is a good question, and I’m not sure I know the answer to it. Keep saying what we need to say as we are here today. In China, that was not possible under Mao. It was not possible under Mao ever since the early 1940s when he began lowering the boom, wanting to create a new man and a new era, bringing on thought reform, rectification, and all the rest of it.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on this dilemma of the officials who know that they are living in crazy times but still want to help the people. What’s the right way to kind of look at what Deng and Zhou and others did in the Mao period?

Orville Schell: They’re always dancing on a razor’s edge. You know, it's not a, a dance I would care to know how to get out of. Fair enough. Some of these people — and Zhou Enlai had a measure of this, I wager — you want to do good by the people but the cost of staying in the game is very high.

The people in the Trump administration, in the first go around, there were a few, some quit and they did in some significant measure keep their integrity intact. And they did do some good restraining things. I think this administration is much harder. He’s bringing in the — Elon Musk is like a leader of Red Guards and the Proud Boys are Red Guards equivalent.

It’s a very difficult human dilemma to know if you want to be in government and you are drawn to political power, how do you do it now? Can you do it? Or should you just become a Buddhist monk or a Taoist priest and just go up on your mountain and wait? I don’t know the answer to that. Us who are writers? Who have not been in political power, don’t want to be in political power. We’re not drawn to that flame. So we do what we do.

Jordan Schneider: Comparing America 2025 to anytime in Mao’s reign, the downsides of recording a podcast like this are much lower.

Orville Schell: For now Jordan, but people have long memories and there are archives and there are a lot of people. The way Xi Jinping’s father fell the second time was over a book about a big leader in northwest Shaanxi province, Liu Zhidan 刘志丹, that he allowed to be published. Mao said, “Well, you’re trying to put too much emphasis on him as the hero, not me.” Anyway, it’s a long, complicated story, but simply to say that sometimes small things done in past, to autocratic regimes like China, are grounds for you being pilloried in the future.

Jordan Schneider: We’ll get into that arc with Joseph later this summer. I’m still feeling okay about our freedom to podcast.

Orville Schell: I’m glad you’re doing it. My virtue is that I’m a little older. I don’t need to be so worried about my future.

Alexander Boyd: Michael Berry talks about this in his writing about Fang Fang — the term míng zhé bǎo shēn (明哲保身) means, “Don’t speak out in order to preserve yourself.” I personally think that in the United States, we have a great privilege to be able to speak out, and we should exercise that privilege.

Orville Schell: We still do. The government in sort of in the shape it’s in, it puts all the more burden on the institutions of civil society. Universities, think tanks, libraries, and community organizations do not owe fealty to the central government, but owe fealty to what they do. Media would be another very important example — cultural organizations, orchestras, operas, whatnot.

Alexander Boyd: Trump has shown an immense fascination with the Kennedy Center in D.C., which is where I’m based. I think it was Cats that was his favorite.

Bach and Bloodlines

Alexander Boyd: Let’s talk, Orville, about bloodline theory. What was bloodline theory during the Cultural Revolution? Why did it matter? Mao himself wasn’t an endorser of bloodline theory, but it did have a lot of influence.

Trump always talks about genes. “It’s all in the genes.” Quite recently, he weighed in on the NFL draft about a quarterback who’s sliding, Shedeur Sanders, and saying, “He has phenomenal genes. They should have picked him because his dad was such a good player.” Is bloodline theory another parallel with the Cultural Revolution ?

Orville Schell: During the Cultural Revolution, the notion of bloodlines worked like this: if your father was a hero, so you were good to go. But on the other hand, if your father was someone of questionable background, then you bore that stigma. You were placed in that class category because families were categorized based on their class background.

As you all remember, Mao had this notion that certain classes had rights and were revolutionary, while certain classes — like the bourgeoisie and landlords — didn’t have rights. The bloodline concept was very pernicious because it meant that if your father was labeled as a counter-revolutionary, a rightist, a capitalist roader, or a bourgeois element, the children inherited that stigma through blood.

That’s why it’s fascinating to delve into familial relationships in any Chinese family. Xi Jinping is the most important case here because he’s now the leader. But I should also mention that in my experience — and this may be better explored in literature than in nonfiction — there’s a cascading effect. All the harm, damage, and attacks that occurred throughout the fifties, sixties, and seventies in China have endured across generations in the Chinese families I know, going from grandfather to father to son to grandson. They persist like microplastics in the ocean — they’re forever chemicals in a way.

We’ve paid no attention to this phenomenon. The way these experiences deranged families, destroyed people’s ability to respect and love their parents, caused betrayals of friendships, and led to the savage attacks that people inflicted on one another — Red Guards attacking their teachers — all of this continues to reverberate.

This trauma isn’t something you get over the next day, and it lives on in ways that are very difficult to analyze. There’s no data, and China doesn’t have a vigorous psychoanalytic tradition to help people understand what influences may have been passed down to them through their experiences with parents who suffered.

The Cultural Revolution was deep, and its consequences are enduring. That’s why, when Deng Xiaoping came to power and waved his wand to rehabilitate people, saying it was a new era, I felt incredibly skeptical. I believed there was a whole residue of impact deeply embedded within society and human beings.

There had been so much damage — not just Mao and the party treating people badly, but people being forced to treat their spouses badly, their children badly, their relatives, friends, and colleagues. This is something that endures.

Alexander Boyd: This endures in China to this day, you argue. When was your most recent trip back to China, and how do you see it enduring today?

Orville Schell: My most recent trip was just as the COVID pandemic hit. All you have to do is talk to your friends. I have a friend who went to Harvard, had a very difficult time with her parents, grew up in China, and she set up a group for Chinese women similar to her to discuss this. I found that incredibly interesting.

Some of the things that they stumbled upon as they were trying to analyze the relationships they have with their parents — how are they influenced by the relationship their parents had to their parents and to society, and power. Very few people have wandered into this field.

Robert J. Lifton, a wonderfully brilliant psychoanalyst who wrote Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism in the 50s and then Revolutionary Immortality about Mao’s quest to make himself immortal so that his legacy would live on. There have been very few people — Lucien Pye, Richard Solomon — who’ve actually looked into the human element. That’s why I wrote a novel, because I felt I couldn’t touch it as a nonfiction writer. I didn’t get to the question of the role of religion, music, culture, love, family. All of these things are abiding human concerns.

Alexander Boyd: You titled that novel after a Lu Xun 魯迅 essay. How come?

Orville Schell: I love that essay, My Old Home (故鄉). It’s a very wistful essay about returning home after things changed. My novel was about a classical musician and what happened to him when he returned back to China in the 50s as a lover of Bach.

If I may say so, there is no human being whom I think is more antithetical to Chairman Mao than Johann Sebastian Bach. In fact, I want to write a play called “My Dinner with Johann,” where they have a conversation. Because Bach was all about religion. Mao Zedong was all about the external. Something’s wrong? It’s out there, not in here.

Yes, Confucianism did have a notion of self-cultivation, but it’s not like Christianity.

Jordan Schneider: Well, we have to end with the ChatGPT imagined conversation between Bach and Mao.

Orville Schell: There was a show Henry Kissinger went to, and Robin Williams started wandering down the aisle afterwards. He passed Kissinger, and he was saying things to people as he went. He said, “Oh, Henry, love all your wars.” I could imagine Bach starting off by saying to Mao, “Love all your revolutions.”

Jordan Schneider: This is how we’re going to start. Rewrite with Bach saying sarcastically to Mao, “Love all your revolutions. ” Alex, you’re Bach. Let’s go.

Alexander Boyd: Love all of your revolutions, Chairman. Tossing the world upside down seems to be your favorite key signature.

Jordan Schneider: Upside down is where history finds its balance, Herr Bach. The masses must turn the old order on its head to set it upright.

Orville Schell: Now you’re talking like a robot, like a propaganda minister. I think Mao would say, “Tell me, Johann, what’s all this about Jesus? Why are you so obsessed with Jesus?” That would get Bach rolling. You remember when Clinton was in China, where he went into the Great Hall of the People for the press conference. At one point, Jiang Zemin, completely sui generis, said to Clinton, “Mr. President, I have a question. Why are so many Americans so interested in the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism?” He was speaking in Chinese. Of course, Clinton went on a tear. But I thought that was a sort of interesting question to ask. You can’t imagine Xi Jinping asking such a question.

Alexander Boyd: What did Clinton say?

Orville Schell: Clinton said something like, “Chairman Jiang, I think if you had a chance to meet the Dalai Lama, you’d really like him.” Jiang, who’d been off script and bantering in a very nice human way with Clinton, grabbed the podium and, as I recollect, he said, “With your permission, Mr. President, shall we close this section?”

Jordan Schneider: What are you reading right now?

Orville Schell: I’m reviewing this Torigan book for Foreign Affairs. I’ve also been reading William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Timothy Ryback’s book about 1931 and ’32 in Germany, and a Robert Paxton book on fascism.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about Rise and Fall of the Third Reich for a second. What stuck out to you about that book?

Orville Schell: I’m very curious where we are on this sort of scenario — how Germany headed off into fascism and the Third Reich. It’s pretty frightening when you look back at the various steps, at what happened and who didn’t say anything, who just shut up.

There’s a wonderful diary of Victor Klemperer, who was the cousin of a famous conductor. He kept a daily record of what happened. He was Jewish, his wife was Catholic, and he lived in Potsdam. They keep saying, “Surely something will happen, surely someone will come, and that can’t be it. Surely the Allies will come in.” Of course, they didn’t. We ended up with Hitler being elected Vice Chancellor, then we’re off to the races.

I’m very interested in how things slide into this state where you end up with an autocracy. Remember that Germany was the highest form of European civilization, and yet you ended up with Hitler.

Alexander Boyd: I’m also reading Hitler-specific these days. I’m reading Ian Kershaw’s two-part, two-volume biography of Hitler. I just finished Hubris and now I’m onto Nemesis.

Jordan Schneider: Orville, do you know Ian Kershaw? I’ve been trying to find his email address.

Orville Schell: I don’t know him but he would be great to get on and just walk him through the steps. There are some wonderful, wonderful books about that period that we need to know more about. Because you see how a slow erosion step by step, step by step with a kind of charismatic crackpot leader leading the charge and how it happens and how people just don’t rise to the occasion to stop it. They think, “Oh the courts will do it, oh something will do it,” but sometimes they don’t.

This is why I think comparing Trump to Xi is interesting and worthwhile doing. Although some of your more rigorous scholars may think there’s no data, no theoretical constructs, but for me it’s the heart of the matter. It has a lot to do with how people grow up. Autocratic leaders write themselves as very large — democratic leaders don’t have that opportunity as much. When you’re in big leader culture land, whether Putin, Kim Jong Un, Xi Jinping, Orban, whoever, it really matters who they are and where they came from and what their sort of operating system is, who installed it and when.

You can say fairly safely, although there are a lot of amazingly wonderful people in China — I have to say, and I married one — but the Cultural Revolution created massive amounts of personal, psychological, intellectual damage. It wasn’t just people got killed, people got in jail for a little while, and then Deng waved his wand and it was all over. That’s not how historical trauma works.

That’s why I find Torigan’s book so interesting. To his credit, he doesn’t do what I’ve just done, which is draw conclusions or try to draw gratuitous conclusions. He just tells the story. It’s a monumental job of research. You can draw your own conclusions, and that’s what I intend to do in Foreign Affairs.

Alexander Boyd: Any hints on those conclusions that are coming out soon?

Orville Schell: I want to make some surmises about what growing up in the Cultural Revolution meant to the formation of Xi Jinping, his form of governance today.

Alexander Boyd: According to the book, Xi Zhongxun, upon hearing of the Cultural Revolution, actually asked for his soul to be lit afire by it, which I found to be incredible research, obviously, on Torigan’s part to get this. Does that indicate that Xi Zhongxun, for whom the Party always came first, was unable fundamentally to connect with Mao because the Cultural Revolution was ongoing? He was already purged, but he yearned desperately for this. It’s kind of like a priest who doesn’t hear God’s voice calling. Is that a correct analysis?

Orville Schell: The Party — and Zhou Enlai suffered from this too — they all did. Some of them did have a sense that something was deeply awry. But there was no other show in town except the Party and the Revolution. They were veteran revolutionaries.

Xi Zhongxun, no matter what they did to him, and what they did to him was pretty horrendous, though not the worst, he never lost his belief in the Revolution and the Party. That’s what he imbued his son with. Yes, bad things happen. We can’t have chaos again. But the party is fundamentally right. The revolution cannot be questioned.

It’s a classic case of where people have no other place to turn except run off into the hills if you can. And we see this in our own government now. People desperately wanting to be in the limelight, in power, in government. And they have all kinds of rationalizations. Rubio, my God, he used to think Trump was a buffoon. Now he’s sold his soul. Read Doctor Faustus.

Jordan Schneider: My favorite line with Rubio is there’s an old New Yorker profile of him where he reads The Last Lion, the Churchill biography. And he said he read it twice and that he saw himself as Churchill, like warning about the Nazis. The analogy was Iran getting the bomb or something. But to go from that to where we are today is something.

Orville Schell: Power is an incredible intoxicant. Once you get that needle in your arm, that’s your currency and that’s your realm. It’s very hard to imagine what else you’re going to do with yourself. That’s why as a writer, I’ve always said, “No, not going there.” I’m just going to stay a lowly scribe. I don’t even particularly yearn to go to China now because I know if I did yearn to go, that would circumscribe me, it would make me feel I couldn’t say certain things because I’d know there’d be consequences.

I told you this, Jordan. In 1991, I did a year-long project with 60 Minutes on forced labor and the Laogai system. It aired. It was incredible. We got into prison camps. I kept a diary of it, and I edited it and sent it to The New Yorker. They edited it and were about to go into print and I looked at it and said, “I can’t publish this.” I was a younger man, I had a Chinese wife, and I had parents-in-law in China. I threw it in a box.

I pulled it out two years ago and thought, “My God, the question of forced labor in Xinjiang is more relevant than ever.” I took it out. That will be the end of me in terms of grace from the Chinese Communist Party. But that’s okay. I’d rather that than I can’t write and say what I think. I think I was right to put it in a box then. But that’s not a healthy tendency for any society. You remember chōutì wénxué (抽屉文学), “drawer literature,” things that people could only write and put in a drawer.

Jordan Schneider: Benjamin Nathan just won the Pulitzer Prize for this really awesome book To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement, which folks should also read.

Orville Schell: Perry Link is sort of the avatar of the Chinese version of that. I recommend his book on Liu Xiaobo, and he’s just written another book, The Anaconda in the Chandelier. I think that’s a really important question.

You know, intellectuals are poor, weak creatures, and those who stand up — read Blood Letters. Alex, will you send Jordan the Elaine Pagels program we did on the comparison of Jesus and Lin Zhao? We had them both on stage talking about the role that faith plays in adversity and revolution. We started off with Bach, a beautiful aria. I wanted Bach as the avatar of being in the mix. You’ll enjoy this, Jordan.

Jordan Schneider: All right, well, we’ll put it in the show notes as well.

Orville Schell: It’s hard to explain to people, but if you watch it, you’ll understand.

Alexander Boyd: On Orville’s note on publishing and not publishing, we just published an excerpt from Perry Link’s forthcoming book, The Anaconda in the Chandelier.

Jordan Schneider: All right, thanks so much for being a part of ChinaTalk, Orville.

Orville Schell: As always, it’s a great pleasure. You have a great program, Jordan.

The sections on the “Red-vs-Expert” problems and the “Coalition of the Weak” really got to me—I’ve been thinking a lot about my role as one of those young non-Red experts trying to be useful but looking at a government that wants loyalists.

I get Fang Fang’s line on not speaking out to preserve myself. I’m blogging, but this is a fake name. I’m not ready to torch my career yet…

I might pick up that Benjamin Nathans book! I’m reading up on post-Stalin Soviet Russia for completely recreational and non-preperatory reasons, and that book on dissidents would pair well against Alexei Yurchak’s account of people who just unplugged from the politics.

Gents:

This is an enjoyable conversation, but I fear that the talk of personalities, albeit important, somewhat occludes the trajectory of actual ideas.

Marxist views about the alignment, or not, between economic base and superstructure—key to a deeper understanding of Yan’an, the Great Leap and the CR—offer insights into the real anxieties of Mao and his ideologues, in particular Zhang Chunqiao, the main thinker behind the Socialist Education Campaign and the CR.

This also deserves discussion vis-a-vis Chris Rufo’s “American Cultural Revolution” and Russell Vought’s “Project 2025”.

Xi Jinping’s “restoration” is a similar idea-led “correction” related to the economic and ideological spheres… a subject I have rabbited on about for the past decade. But, many thanks for this sprawling and insightful exchange. Orville, he of ten-thousand years, remains formidable.

Geremie