Matheny on RAND’s Legacy and Future

“We live in an extraordinary period. If we can navigate these risks and put up guardrails, the upside potential is phenomenal.”

Jason Matheny recently passed his first anniversary as CEO of the RAND Corporation, the legendary federally funded research organization founded after World War II that now has nearly 2,000 employees and over $350 million in annual revenue.

Previously, Matheny led the Biden White House’s policymaking on technology and national security at the National Security Council and Office of Science and Technology Policy. He also founded the Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University and directed the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, which develops advanced technologies for the US Intelligence Community.

He is also great on the mic. We spent two hours together putting together one of my favorite conversations this year.

We discuss:

How RAND balances researcher freedom, long-term problem-solving, perennial budgetary constraints, and political imperatives.

Why Matheny looks for, of all things, kindness in hiring and promoting top-notch talent.

How RAND’s structure allows researchers to self-organize.

RAND’s sense of “optimistic urgency” and counterbalancing the weight of existential risk with existential hope for the future.

RAND’s tradition of methodological innovation in the shadow of catastrophe.

Why biosecurity risks are so prevalent … and likely to escalate.

How bureaucratic politics can lead to insane decisions and existential risks.

Takeaways on the drawbacks of the current methodologies driving decision-making on the NSC from his time in the White House.

The upsides and downsides to tech moonshots, and why OpenAI leads the pack.

How art informs our thinking on tech and public policy.

This interview is brought to you by the Andrew Marshall Foundation and the Hudson Institute’s Center for Defense Concepts and Technology. They’ve been generous enough to sponsor a series on the impact of technological change on bureaucracies and operational concepts.

Do check out the full podcast, I promise it will be worth your time.

The Flaring of Intellectual Outliers

Jordan Schneider: You pointed me to a 2014 paper published by the Andrew W. Marshall Foundation titled, “The Flaring of Intellectual Outliers: An Organizational Interpretation of the Generation of Novelty in the RAND Corporation.” This paper attempts to frame how RAND and other organizations like Bell Labs were able to do the seemingly impossible in generating novel research.

Albert Wohlstetter, one of RAND’s famous early social scientists, said he was attracted to the organization because of the enormous latitude it gave researchers, bridging practical and theoretical projects.

He was shocked to see RAND publishing on super random stuff like geometry, which was far from what the Air Force probably thought they were signing up to get when they just wanted better bombing targets and more efficient planes.

Today, RAND is mostly known for its practical policy research. What does research as a source of practical ideas mean to you?

Jason Matheny: There was a sense that to attract really smart researchers, RAND had to give them enough latitude so that they could do basic research on geometry or on causal inference. But you actually wanted them to work on practical problems that were going to be relevant to US policymakers.

In some ways, the freedom was a way to get people in the door.

A lot of the problems that had practical utility were also intellectually interesting and fascinating. Finding these attractants for really smart people is important. Self-determination is certainly one of those — the entrepreneurship that RAND has, where most of the researchers are picking their projects.

They’re self-organizing. They’re not given much top-down direction. That is an important part of the recipe for a place like RAND.

We’re pretty clear with folks when they’re applying to RAND that they’ll be spending their time working on policy analysis. They won’t be doing a ton of basic research, but you can do some. For people who come from academia and want to be working on hard problems that are actually going to matter, it’s great.

They didn’t just want to do publications for peer-reviewed journals that were making some methodological innovation that wouldn’t actually impact an important decision. They didn’t want to go through the whole tenure process in order to achieve institutional goals for a university.

What they really wanted to do was affect some consequential policy in national security or education or healthcare. There’s a selection effect.

The folks who want to join RAND might have come from an academic research background, but they’ve been dissatisfied with it because either it didn’t have enough practical relevance, or the mix of practical relevance versus research ambition, or because they just got frustrated with the incentive systems within academia that pulled them away from things with some policy impact.

One of the things that makes RAND unusual is our size. We have 2,000 people and we work across so many different disciplines.

Say a labor economist comes in because they want to work on labor displacement in the United States. But then they see a colleague who’s working on some really interesting analysis of labor and dependency ratios in China. Then they say, “Well, I’m interested in that project.” We do find a lot of people who come in the door because of one topic, but then quickly start working on a range of other topics.

It’s a great environment for informational omnivores, for people who are just broadly intellectually curious, even outside of the domain they specialized in, maybe in their earlier research career.

Jordan Schneider: Even in 1960 you had folks saying that going from 200 to 1,000 made multidisciplinary collaboration a lot harder. It became large enough that scholars from the same disciplines could get lunch together and not branch out. How do you keep multidisciplinarity alive even as the silos expand?

Jason Matheny: To what extent does size present opportunities versus costs? Early RAND wasn’t that small. We had about 500 employees with hundreds of projects at any given time. Bell Labs had about 15,000 employees in the mid-1960s.

You can have highly innovative organizations that are large and that draw on the infrastructure of large institutions.

For example, CSET is relatively small, but it’s within the much larger institution of Georgetown, which has thousands of people. It’s able to draw on that infrastructure.

You often see highly innovative groups within larger organizations. It makes sense to think about what makes those groups particularly good at doing research or analysis. There’s also a lot of bang for the buck in thinking about the mechanisms or processes that allow groups of different sizes to be effective in producing research and analysis.

One factor is having a sense of optimistic urgency — actually having a sense that the problems that you’re working on should be really important and can be really important, and you’re probably actually not duplicating other work.

We tend to overestimate the number of people who are working on the most challenging and important problems.

There was a guy at Bell Labs, Richard Hamming, who had a lecture on this topic that he would give. He was known for inviting himself to people’s lunch tables at Bell Labs and sitting down and asking people, “Are you all working on the most important problem? And if not, why?”

A lot of folks, just by inertia, aren’t necessarily working on the thing that they think is most important — just freeing up people’s sense that they could be working on the most important problem.

Living with Leviathan

Jason Matheny: We’re celebrating our 75th anniversary this year. One of the things I’ve been looking at are the periods in RAND’s history when we’ve had political backlash or policymakers who are unhappy with us.

I actually don’t think it’s been worse today in terms of the feedback or pressure we get politically than it has been historically. Part of the reason for that is the people who are generating most of the questions for RAND.

The folks within government are mostly civil servants. They’re folks who are not highly politicized. They’re folks who are not turning over from administration to administration. They’re people who have been spending 20 years working on a set of really hard problems related to defense policy or national intelligence or education policy or the other things in our portfolio.

Every once in a while, we’ll get some angry letters from folks about some analysis that we do, but we keep on working.

We have maintained our reputation and our credibility on both parts of the political spectrum pretty well over the last 75 years. We’re just generally viewed as being a set of nerds who are just really committed to getting the facts right.

Sometimes the facts are inconvenient. Sometimes folks don’t like the results. But that is not politically motivated.

One reason we’ve had this project on “Truth Decay” at RAND is because we realize this is not only an important issue for American society, it’s also an important issue for analytic institutions like RAND, whose entire business is organized around trying to figure out what the truth is.

Jordan Schneider: RAND initially had something of a blank check from the Air Force, and Open Philanthropy gave you a lot of latitude in the early years of CSET. But that’s not necessarily the same organizational structure that you’re living with today. What are your current constraints and how are you working around them?

Jason Matheny: As a percent of our total budget, it’s true that we’re more constrained than, say, early RAND or CSET. But in absolute terms, there’s as much or maybe even more unconstrained funding here right now. That’s all thanks to foundation funding or especially ambitious analytic efforts that we’re working on for places like the Office of Net Assessment. The work that comes out of that is some of the most interesting and effective work at RAND.

Mike Mazarr’s work on the social foundations of national competitiveness is as interesting as the work that Tom Schelling and others did at RAND.

I do think that the level of general government oversight over contracts has increased a lot since the 1950s. Much of that for the better, I should say. As a taxpayer, we probably did need more discipline on how we were spending federal dollars immediately after World War II, but that does have a cost for analytic organizations.

Now, there’re still a lot of open-ended projects at RAND, and we also have a lot of open-ended positions at RAND. We just recently put out a call for applications for a Technology and Security Policy Fellowship, which is open, and hope listeners who are interested in that topic will apply.

About 80 percent of the time is open to the fellows to decide how to spend it. It’s pretty great. There’re very few things like this in the research world. Then 20 percent of the time is spent working on policy analysis for actual policymakers.

You get the best of both worlds. You get the benefit of having some self-directed study, and the benefit of working on real projects that allow you to interact with an assistant secretary of defense or assistant secretary of state or other senior policymakers.

Jordan Schneider: This balance between independence and influence is another thing that Andy Marshall harped on as one of the keys to RAND’s success. How do you think about the trade-offs there?

Jason Matheny:

In some ways, RAND is probably more influential to more policymakers today than it was then.

RAND is known for pushing back on the questions we’re asked and saying, “You’re asking us the wrong question. The more important question is X, not Y.” We still do that.

When a federal decision maker comes to us with a question, and if we think it’s not framed well or there’s a bigger question that deserves to be asked, we’ll provide that feedback.

Now, ultimately, it’s the sponsor that’s paying us, and they own the question. We own the results. We don’t take direction on what the product of the analysis should be. That’s something on which we maintain a really fierce independence.

Maybe a third of the time we’re actually able to persuade the sponsor there’s a better framing for the question, that it can actually help them make a decision in a way that’s going to be more relevant.

There’s an Eisenhower line about this. Whenever you face a big problem, try to make it bigger.

If you can solve the more general class of problems, it not only can be more efficient analytically, it can also just prevent certain kinds of mental shortcuts. Whenever we can, we try to make the more general case on the topic of the analysis rather than the more tactical case.

The Best Time Was Yesterday

Jordan Schneider: There’s this great line in “The Flaring of the Intellectual Outliers” talking about the early years of RAND:

In some mysterious way, an urgent pressure for relevance became an urgent pressure for fundamental research and ideas that were relevant in the long term. It is as though a string quartet stranded in a winter snowstorm decided urgently to compose a new fugue rather than start shoveling.

How do you make sure that long-term focus is still part of RAND’s culture?

Jason Matheny: Andy had a very particular view. Not everybody at RAND felt that way about RAND.

Read Andrew May’s history of the early years of RAND. His dissertation is maybe the most complete history [of that period]. Or read, as I’ve been doing, memos from across the staff at RAND in the late 1940s and 1950s and even in the early 1960s. There were a lot of folks who felt like they were just turning the crank on analysis that wouldn’t be that relevant.

Certainly, the work done by Andy Marshall and other memorable figures at RAND had a more general approach to strategic analysis.

The sense of urgency was one that some RAND staff felt acutely. It was driven in part by the risks of the day that were collectively felt across the country.

There was a real risk of nuclear war. There were RAND staff who chose not to have a pension because they didn’t believe they would actually survive until retirement. They thought it was more likely that they would die in a nuclear blast.

It’s certainly hard to recreate that sense of urgency that was maybe felt broadly in the 1950s and 1960s.

But there are certainly parts of RAND that still feel that urgency. For instance, a lot of the folks here working on AI policy or biosecurity policy feel that sense of urgency. Folks who work on Taiwan analysis feel that sense of urgency.

It’s not to say that other folks are feeling sanguine about the portfolios that they’re working on. Education or healthcare policy are urgent in a different way. We’re not all going to die if we don’t get an education policy that’s more effective, but it’s a lower and slower existential risk if we don’t figure out those problems that are consequential for US policy and global policy.

There’s still a very high degree of mission focus and motivation at RAND. This is also a selection effect at RAND.

People who come here want to be working on problems that are consequential. Maybe they want to make a methodological contribution along the way. But the main reason that they’re here is because they want to solve a problem that’s important for humanity.

War Games, What Are They Good For?

Jason Matheny: We need to figure out how to design analytic tools and processes that are well-fit for the kinds of challenges we face in the 21st century. We had a set of tools and processes that we developed in the early years of RAND and continued to refine. Many of those are still just as relevant today.

I asked Andy Marshall once, “What are the most important methodological innovations that RAND made? Was it the advances in deterrence theory, game theory, rational choice, or some modeling and simulation work?”

He said, no, it wasn’t any of that.

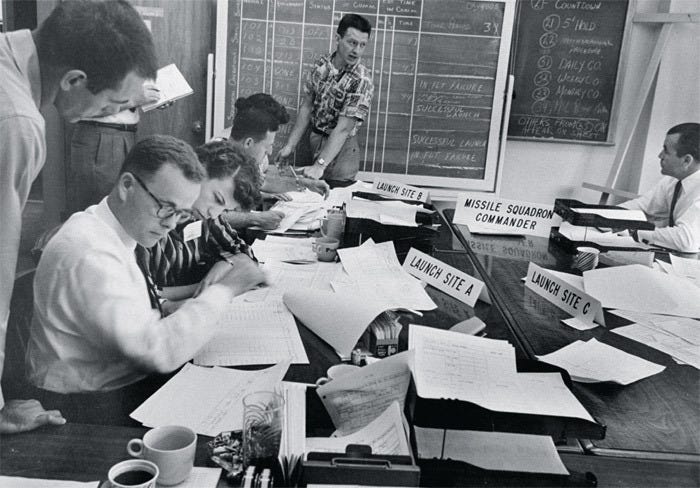

The most important methodological contributions from RAND were in war gaming. He said the war games were the things that actually got decision makers to realize that they had made assumptions that weren’t realistic.

They allowed decision makers to run through a variety of scenarios, test different strategies, see where they broke down. That was a really interesting insight.

It’s not the fancy analytic work. The war gaming work does not tend to involve something that you could publish as a new research methodology paper. It’s more about getting real decision makers to a table and having them work through a bunch of different scenarios. A lot of that work ends up being highly classified because the details of the war games actually matter.

We probably conduct more classified war games than any other think tank or institution. The output of that is something that continues to be among the most valuable things that RAND does.

That is an example of a 20th century innovation that is just as relevant today.

There are also other things that we can do now that we couldn’t do in the 1950s or 1960s, like massively crowdsourced analysis. We just didn’t have the tools for that. We didn’t have the Internet. We didn’t have a way of distributing analytic work or questions to widely distributed expertise.

We also need to be thinking a lot about how to fully leverage advances in AI for analysis.

Personnel Is Policy

Jordan Schneider: Building CSET from scratch and leading a seventy-five-year-old research bureaucracy seem very different. What have you learned from your past year as CEO of RAND?

Jason Matheny: I’ve worked within organizations that are brand new, like CSET, organizations that are new but already have a ton of processes that you have to work within, like IARPA, and organizations that are pretty old and have even more processes, like the National Security Council.

RAND is in that final category. We have 75 years of history. It’s a mid-sized organization. You have to be very careful about making structural changes that are going to affect 2,000 people’s lives. You’re going to take more effort to change or undo change if you find out it was a mistake.

Something common across those organizations is that hiring and promotion are incredibly important. Among the most important decisions we can make are just about personnel. There’s the line “personnel is policy.” Personnel is at the heart of any organization’s likelihood of success. Most of the variance and outcome of a project is related to the people who are working on it.

Spending a lot of time thinking about the people who are on a project — how to get the right team working on a project — is essential. For RAND, CSET, and other places I’ve worked, it’s a combination of finding people who are not just brilliant and hardworking, but also kind.

Kindness is often underrated. Sometimes managers think, “Well, so-and-so is a jerk, but they’re so brilliant it’s worth hiring them or keeping them on.” In my experience, that very rarely works out.

The work that I’ve done has been predominantly team-based. No one wants to be on a team with a jerk. If you hire jerks, you lose the other talent on your team.

It makes sense to have organizations with a high tolerance for eccentricity and quirkiness. It’s one of the things that I love about the places I’ve worked — IARPA, CSET, and RAND. RAND has a ton of quirkiness that I adore, but there is no unkindness. I don’t think there’s room for that.

Interpersonal compassion is highly correlated with impersonal, intergenerational compassion — the sort that we’re going to need a lot of if we’re going to safely navigate the challenges ahead.

So far, I found that the changes we’ve made within RAND to make processes more efficient — to figure out how to take on these big challenges — they’re not changes that have required me to give orders from the mountaintop on stone tablets.

It’s actually something the researchers here have been really enthusiastic about — taking on these big problems and reducing the amount of process and bureaucracy. It’s going pretty well. I’m really optimistic about the things that we’re doing here.

Jordan Schneider: How do you test for kindness in an interview?

Jason Matheny: We tend to do a fair amount of interviewing at RAND. Our researchers come in and have several different interviews in different settings with different groups of researchers. One question we ask is to describe a situation where somebody you were working with was really struggling with a personal issue. How did you help them with it?

We also have questions about interpersonal compassion in some of the interview panels, particularly for some roles that focused on long-term issues. How do you think about compassion towards future generations that are going to be affected by a policy decision?

I don’t think we have any magic solution to figuring out how to make sure that folks that we hire are kind and compassionate. There’s some amount of self-selection.

They’re given a lot of clarity that the work they’re going to be doing is team-based. They’re going to be interacting a lot with other people.

The Self-Organization of Inquiry

Jason Matheny: Somebody who’s your boss on a project one day might be working for you the next day because the teams themselves shift. You’ve got principal investigators on one project who are team members on other projects.

It’s relatively flat. The researchers mix up the hierarchy constantly depending on the project. That reinforces the need for compassion. You don’t know who you’re going to be working for or whether you’re going to be the boss on the next project.

Jordan Schneider: RAND’s early hiring practices wouldn’t necessarily fly today. They seemed to rely on “old boy” networks and hiring people they thought were smart but weird. Somehow this led to thirty-two Nobel laureates passing through RAND over the years. Maybe this was due to intellectual competition. Is there room for that kind of competition at RAND today? Can it be done in a healthy way?

Jason Matheny: To what extent does competition within an organization motivate good work? Does it lead to a lot of wasted effort in jockeying for position? There is a balance between competition and collaboration that RAND tries to achieve.

One interesting feature of RAND is our internal labor market where people self-organize to pursue projects. It’s competitive, but people are competing to be on a team.

The overall emphasis on team-based, interdisciplinary work means that the people who succeed here are pretty pro-social. They’re people who are capable of collaboration. We don’t have many projects that are solo efforts.

We do need to figure out ways of aligning incentives with analytic work, including outside of RAND. To what extent can we set bounties or prizes for certain kinds of analysis? Can you award money for analysis that makes a decision better?

I would love to see more prediction markets — providing incentives for creating greater accuracy in judgments. We don’t have a policy that allows large, well-funded prediction markets to be used by society. That’s probably holding back. A lot of opportunities for creating these incentives for accuracy would be really useful for policy analysis.

Jordan Schneider: The early days of RAND had an aggressively hierarchical structure with giants like John von Neumann at the top. But the average age in the 1950s was 27. I don’t think that’s what RAND looks like today. What’s the optimal mix of junior and senior staff?

Jason Matheny:

For a lot of research areas, you want a mix of senior, mid-level, and junior researchers working on projects.

Senior researchers cost more. On a given project, it’s usually less of their time that’s spent on it compared to more junior researchers. Often, they’re playing the role of mentor, helping to point out some similarity to another project that we’ve done at RAND.

Also, because we have a graduate school at RAND, there’s a pedagogical component to this that’s just embedded in projects. Many of our researchers also teach at the graduate school.

They just feel a certain responsibility for making sure the next generation of policy analysts are equipped — that they’ve got the analytic tools and the dispassionate approach needed to pursue the truth relentlessly.

That is reflected in the way our projects are run. We aspire to have a pretty uniform distribution in seniority. The very early years of RAND certainly had that. It skewed younger, but then after about 15 years it was starting to become more uniform. We now have a bit of a bimodal age distribution.

There wasn’t much hiring during the pandemic. We’ve grown a lot in the last ten or so years. Right now, a lot of our hiring is at the junior and mid-level. Other things like the introduction of fellowships to RAND will help hiring in some areas like AI and synthetic biology.

Wonks of Change

Jordan Schneider: What kinds of change are you hoping to drive within RAND in the years to come?

Jason Matheny: RAND has an interesting matrix structure. We have research departments where the researchers are hired and mentored, and then research divisions where the projects occur. This allows the researchers to mix and match along projects in different divisions.

RAND also manages four federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs), which are like think tanks for parts of the government.

We have FFRDCs for the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Air Force, the Secretary of the Army, and the Secretary of Homeland Security. Those operate a little bit differently in that there’s just a steady stream of funding.

There’s a set of strategic priorities that RAND works on with the respective secretaries and their deputies and staff. Those are groups of a few hundred people at any given time working on different projects.

We need to be thinking about the things that truly cut across our divisions. Our China work is in that category. So is our work in technology, climate and energy, and some of our work on strengthening democracies and resilience against truth decay, disinformation, political polarization. Our work on inequality and inequity cuts across our domestic and global work.

We have seven offices at RAND. Three of them are overseas in the UK, Australia, and Brussels, supporting our work with allies. We need to figure out ways of leveraging our reach across geography, disciplines, classified and unclassified work, and our own graduate school talent pipeline.

I’m mainly interested in how we can find enough diversification of operating models within RAND that we can run lots of micro-experiments, and we can have people self-organize based on project type, so that the organizational design matches what the project is attempting to do. There’s a ton of room for experimentation.

For any listeners or readers who are really interested in organizational experiments, RAND is a great place to conduct those. Historically, we’ve had all sorts of different designs. Today, we have at least a dozen different kinds of business models and operating models that are running in parallel.

It’s a great place to run experiments like this. I’m a really big fan of Heidi Williams, an economist who thinks a lot about innovation and organization. There’s so much to be done in this general category of organizational and mechanism design on how we can produce better research and analysis.

“Optimistic Urgency”

Jordan Schneider: In what ways might you have surprised RAND’s board and its employees?

Jason Matheny: Folks pretty much knew what they were getting. I was somebody who came in knowing a little about a few areas of policy and not being an expert in a lot of the areas where RAND works. We have so many areas. I won’t ever hope to be able to be an expert in most of the things we work on.

But they also knew that I was going to be fully dedicated to making RAND the best workplace that I can make it and to make the work here easier.

That means reducing process spending and trying to make sure that we can get research results faster and supporting staff so their lives are happier — so they can accomplish more with their time and take on incredibly consequential things for the future of the country and the world.

Having a sense of “optimistic urgency,” as Andy Marshall put it, is a key part of that.

We don’t need to feel that the world is about to end to have that sense of urgency. We can also just feel that the opportunities are so great that there’s not only existential risk, there’s also existential hope.

We live in an extraordinary period where so much technological change is happening that can have incredible applications to improving human health and human prosperity.

If we can manage to navigate these risks and put in the guardrails, the upside potential ahead of us is phenomenal.

Methods of Madness

Jordan Schneider: RAND made a lot of methodological innovations during the early Cold War. These efforts were downstream from a larger purpose — trying to stop a nuclear holocaust.

It’s not shocking they developed interesting theories on strategic bombing or nuclear weapons. But they also came up with more foundational innovations in modeling and computer science so they could construct those theories.

Given the specter of existential risk today, how is RAND continuing its tradition of methodological innovation?

Jason Matheny: Our current work on decision-making under deep uncertainty falls into that category of methodological innovation. It’s really important work.

This research program contrasts with work that I had been involved with earlier on generating precise probabilistic forecasts of events. This is sort of the other side of that.

Let’s say that you can’t produce precise probabilistic forecasts, and there are a lot of important problems in that category. How do you make decisions that are more robust? There’s a long line of research, as you note, treating methodology as a tool that supports high-consequence decision-making.

The Delphi method would be an example of this. It’s still one of the most useful and probably underused tools for judgment and decision-making. It’s a way of eliciting forecasts or probability judgments and combining them in ways that are less prone to groupthink and various kinds of biases. That type of work continues at RAND.

I’m really interested in building on this. Are there other tools and processes that can advance analysis on the most consequential problems in policy that we’re not yet widely using? That could be crowdsourced forecasts, prediction markets, or prizes and bounties for finding analytic information outside of RAND.

Figuring out how to leverage the 8 billion brains outside of RAND seems pretty important. We’re just 2,000 people here. There’s a whole lot more knowledge and expertise outside the organization. How do we leverage that? How do we incentivize it?

Applying advances in large language models to analysis is also important — everything from doing literature reviews to figuring out how to elaborate on an outline or generate hypotheses.

Large language models are just a really incredible new research tool.

Jordan Schneider: I wanted to pitch you on making RAND the AI-for-social-science hub of the twenty-first century. Universities are probably a little too fragmented to make the sort of institutional bets that you’d need to really do this.

Jason Matheny:

We are working at RAND to make sure all our staff have exposure and training to large language models, that they think about the ways these models can help their work — not just on the research side, but also on the operations side.

We’re already seeing researchers start to lean on these tools heavily in their work. That’s only going to grow. As we see these tools become more capable, the number of applications — the ways in which they can boost analysis and serve as sort of an amplifier for the cognitive work that’s being done by researchers here — is going to grow.

It still requires error checking. It still requires a lot of editing and a lot of checking citations to make sure they’re real citations and not hallucinations. But we’ve already seen the accuracy improve just over the last few months. We’re seeing fewer of these hallucinated references.

We’re seeing improvements in the ability to summarize a document well, create an annotated bibliography, and find and synthesize work in a domain we’re not actually sure will be particularly relevant to our main analysis.

We wouldn’t necessarily want to spend weeks surveying and summarizing a tangential domain, but we want to get the gist to know whether it’s worth a deep dive. Being able to do that analytic triage is something for which these models are very helpful.

We’ll know within two to three years if someone whose mind is nimble enough can do the RAND multidisciplinary approach as an individual. Hopefully you’ll be able to set it up, even if you’re not a trained economist or sociologist.

You could ask RAND GPT, “As a RAND sociologist, what are the sorts of things I should be looking at?” It could give researchers the power to load new methodological approaches and pick and choose methods.

Jordan Schneider: If you had a year to personally run your own RAND research pod, what topic would you choose?

Jason Matheny: I’d choose something like a strategic look at how we can put guardrails on AI and synthetic biology, comparable to the guardrails we put on nuclear technologies that can either be used for peaceful nuclear energy or for producing nuclear weapons.

We’ve thought deeply about how we create those guardrails for nuclear technologies so that we can get the benefit and reduce the risk. What are comparable guardrails for AI and synthetic biology?

If we didn’t have to worry about catastrophic risks, I’d want to spend more time thinking about how to design and deploy mechanisms for making better analysis and better decisions. I really loved the Phil Tetlock and Barbara Meller’s tournament on judgments around geopolitical events. Doing more of that would be something I’d love to see.

Unknown Unknowns

Jordan Schneider: I want to come back to decision-making under deep uncertainty. I’m worried about it being a very difficult thing for the voting public or politicians to internalize and accept. How does RAND communicate difficult, nuanced research in a way that’s palatable for voters and policymakers?

Jason Matheny: I’ll give an example. We have a research effort at RAND on something we call “truth decay.” We’re trying to analyze the general trend toward the erosion of facts and evidence used in policy debates.

There have been different measures of political polarization over the last few decades. There’s a decline in the way facts and evidence are used in debating policy substance, particularly in Congress. We’ve been doing a lot of work to understand the drivers of this and its remedies.

Even asking the question can be politicized. RAND is pretty nonpartisan. I couldn’t speculate on the broad political views of most of my colleagues I interact with every day. It’s a point of pride for RAND. But in some cases, even asking the question about what’s happening to facts and evidence in policy debates is viewed as politicized.

With decision-making under deep uncertainty, you want to find a set of methods that can help you make robustly good decisions, even when you’re radically uncertain about key parameters.

One example of this is the timelines for different AI capabilities. We don’t really know because researchers themselves are divided.

It was pretty stunning when the “Statement on AI Risk” from the Center for AI Safety was published. I saw the greatest degree of unanimity that I’ve seen among researchers describing AI as an extinction risk.

If you go a bit deeper and ask about extinction risk timelines and specific scenarios we should be worried about, you’re going to see a much greater level of disagreement. Is it AI applied to the design of cyberweapons? AI applied to bioweapons? Is it disinformation attacks? Is it the misalignment of AI systems?

But to see most of the top 50 AI researchers in the world — most of the authors of the canonical AI papers over the last decade — agreeing on this general point about AI posing potentially such a severe risk, that’s the sort of thing we should probably be thinking about.

Jordan Schneider: But Jason … you’re the Phil Tetlock prediction markets guy. You know we can’t simply defer to expert political judgments!

Jason Matheny: The main finding from Philip Tetlock and Barbara Meller’s work in forecasting tournaments isn’t that expertise doesn’t matter. It’s that expertise tends to be distributed in ways that might not always be correlated with conventional markers.

We organized this large global geopolitical forecasting tournament at IARPA, the largest of its type. It involved tens of thousands of participants, eliciting millions of judgments. What was really striking is if you want to make really accurate forecasts, you should involve a lot of people and basically take the average.

If you want to do even a little bit better than the average, you can assign more weight to people who have been more accurate historically, or find groups of so-called “superforecasters” who have a track record of accuracy. But even just taking the unweighted average of a large pool of people is really a pretty great improvement, overtaking the group deliberation of a group of assessed experts.

If you look at some of the surveys that have been done on AI risks, it’s pretty sobering. Robust decision-making in this case means thinking about the kinds of policy interventions that would help on different timescales, even if we don’t have a great detailed sense of what the specific risks are.

For example, are there policy guardrails that can help reduce AI risk, even if you don’t have enough details about the specific risks? Some suggestions might include improving red teaming and safety testing, investing in safety research or lab security, and thinking carefully about open-sourcing, because that’s something you can’t really take back if you detect some significant security issue or safety issue after a code release.

There are a lot of these robust approaches to policy that are helped by the decision-making under deep uncertainty approach — cases where we don’t have precise probability forecasts.

Jordan Schneider: It just seems like people in general and politicians in particular have a hard time internalizing and accepting that the future is uncertain. But there are many possible futures, and we don’t know how things like US-China competition or AI and employment will play out.

Recent congressional hearings on AI seem to follow a pattern we saw with social media. It’s very linear framing. Folks are not internalizing the potential for exponential increase in the power of these platforms.

Jason Matheny: You’re right. There is a general challenge in appreciating exponentials, even just in life. It’s just hard for all of us to see if we’re actually part of a hockey stick curve on an exponential, because it doesn’t look that way at first.

We’re just not good at grasping that. Our brains didn’t evolve to be able to understand changes that happen this rapidly. We see this not just in AI policy, but also in policy around synthetic biology — something that has its own version of Moore’s law happening right now, its own exponential improvements and effects.

We saw during the early part of the pandemic that it's hard to appreciate the doubling times when you have infections that spread, self-replication that is increasing exponentially. We still think linearly about this. We sort of think, “Well, we’ve got weeks to work this out.” But we’ve really only got days at the early part of a pandemic.

It’s the same thing with AI, cyber, and bio. They share this general property of self-replication and potentially self-modification. That makes policymaking especially challenging.

Life Finds a Way

Jordan Schneider: Biosecurity risks don’t seem to resonate with people as much, even though we just had a pandemic. How can we get voters and policymakers to think more deeply about this area?

Jason Matheny: Concern about this goes back decades. You had folks sounding the alarm on our vulnerability to infectious diseases going back even before the signing of the Biological Weapons Convention.

This is part of the point that Matt Meselson was making to Kissinger and Nixon for why we needed a biological weapons convention. We’re a highly networked society. We’re generally contrarian, so we don’t necessarily follow public health advice quickly as a society. We might be asymmetrically vulnerable to infectious diseases, whether natural, accidental, or intentional.

What’s striking is that — despite decades of prominent biologists, public health specialists, and clinicians sounding the alarm on our vulnerability — we have not invested in the things that are going to make the biggest difference for resilience and mitigation of pandemic risk.

Even after having over a million Americans die in a pandemic, we still have not made the kinds of investments that are going to meaningfully reduce the likelihood of future pandemics.

There is a pandemic fatigue right now in the policy community. Much was spent on addressing the economic impact of the pandemic. Some are saying, “Aren’t we done with this as a topic? Can’t we move on?” Of course we can’t, because the probability of something at least as severe as COVID happening again is non-negligible.

We’ve seen how costly it can be. Over a million deaths and over $10 trillion of economic damage — and this was a moderate pandemic with an infection-fatality rate of less than one percent.

We know of pathogens with infection-fatality rates that are much higher. Some are as high as 99%. We face the prospect of highly lethal, highly transmissible viruses with longer presymptomatic periods of transmission, something that makes viruses particularly dangerous.

Those characteristics now are amenable to engineering because of advances in synthetic biology. The risks of an engineered pandemic, whether intentional or accidental, have only grown.

The 1918 influenza, for example, killed somewhere between 50 to 100 million people in twelve months. It’s not clear that we would be any more capable of preventing such a pandemic today.

RAND on China

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned recently that you were excited about potentially setting up an analytic effort that takes a multidisciplinary approach to understanding China. You only have a dozen or so deep China experts on staff. How can RAND repeat its Cold War success in Soviet studies when it comes to China analysis today?

Jason Matheny: We did the math on this recently as part of an assessment of our China work. We have closer to about thirty China specialists at RAND. I still think it’s too small.

At the height of the Soviet studies program at RAND, we had a little under 100 Soviet specialists. We need something of that scale for China.

China studies has to be an interdisciplinary research agenda. It has to involve political scientists, economists, statisticians, linguists, sociologists, and technologists. RAND has comparative advantages here because of our scale and our disciplinary breadth. Having 30 China specialists might already make us the largest effort focused on China, especially in terms of military and economic analysis. But we need to be doing more.

The Soviet studies program at RAND is an interesting model. We had what was then the largest analytic effort in the US.

A large-scale effort with demographers, economists, and linguists focused on things like China’s economy, industrial policy, bureaucratic process — really understanding China’s internal decision-making and closely analyzing the type of advice Xi Jinping is probably receiving and the biases embedded within that process — that is going to be really vital.

We need to be doing more of that. We have some of the essential resources for doing that at RAND. We need to build the others.

Jordan Schneider: What are the limiting factors currently?

Jason Matheny:

One of them is flexible funding. We do a lot of military analysis of China. There is much less federal funding for understanding China’s bureaucracy.

The US Intelligence Community was slow to pivot toward China as an increased focus of analysis. Even within the China portfolio, really thinking about bureaucracy as a subject of intelligence analysis has been slow. Science and technology analysis has been faster, although not as fast as you or I might like.

But really understanding the forms of decision-making — the potential failure nodes in decision-making within Xi’s inner circle — is something really important for us to understand.

Where is Xi getting information about emerging threats and emerging risks? How is that balanced across bureaucratic politics within the PRC? How does it shape the mix of decisions on new technology deployment or Taiwan timelines? Increasing our clarity around those questions is going to be really important.

These are the kinds of questions that are harder to get government funding for. They often seem more abstract. Do we really need sociologists and political scientists trying to analyze the PRC bureaucracy?

Probably the most important work RAND did in Soviet studies during the Cold War was actually focused on these questions. How does the Kremlin actually make decisions? What are its red lines? What are the risks of escalation emerging from this strange bureaucratic politics? These are important.

By default, the research on bureaucratic politics is understudied and underfunded.

Reading Leviathan’s Entrails

Jordan Schneider: The Operational Code of the Politburo, the 1951 classic by Nathan Leites, is worth revisiting.

Books like that on China are the ones I like most. Researchers just interview 200 officials or so and try to piece together a little corner of how the Chinese party-state works.

But I don’t know. Only about one comes out every year, which is really depressing. It’s only going to get harder, if not impossible, to do that research.

Jason Matheny: That’s right. I’m worried our data sources are dwindling.

The analysis of bureaucracies is really important for thinking about strategy.

That’s one thing I really appreciated about Andy Marshall after he moved from RAND to run the Office of Net Assessment at the Pentagon. Thinking about bureaucracies as an important variable in decision-making was a common analytic line of effort that Andy pursued. It really influenced a lot of his thinking about the risks of nuclear policy, for example.

He was accustomed to thinking about how nasty things can get in the world, not because of rational strategies, but because of different kinds of bureaucratic pressures that happen within governments.

A lot of national security thinkers will say it wouldn’t be rational for a state program to do X or launch a nuclear attack or release a biological agent that could have blowback on its own population.

Andy Marshall believed we regularly underestimate the risk and pain tolerance of states and political leaders, especially autocrats. We underestimate the peculiar effects of bureaucracies on decision-making.

Take biological weapons as an example. The Soviet Union had a very large biological weapons program. Each of the laboratories in the program had their own interests in expanding programs. They created prestige. They created job security. They created a lot of advantages for those bureaucrats who could get promotions.

In order to do all that, you need to give scientists interesting problems to work on so your lab can attract the best scientists. You’ve got bragging rights then.

Some of the world-ending pathogens the Soviet biological weapons program worked on weren’t really the product of strategic analysis. Rather, they were something bureaucrats could brag about.

They were things that would be technically sweet for the biologists to work on. If you want to bring together a bunch of smart biologists and say, “Build nasty weapons,” it can be a pretty irresistible intellectual property to have this modified pox virus.

So, they end up with this arsenal that doesn’t make any strategic sense. It only makes sense given the sociology of bureaucracies and technical communities.

More sociological analysis of these communities could end up being really important for what happens in the next few decades. It’s really understudied.

Jordan Schneider: You have folks like Dr. Ken Alibek, who led a bio lab in the Soviet Union, talking about why the USSR, on the one hand, was helping to rid the world of smallpox while at the same time creating the killer smallpox that could end humanity.

When we’re talking about smallpox, plague, or biological weapons, they’d be used in total war.

The rationale which allowed the downstream bureaucrats to flourish was that they understood the US to be evil. “They want to destroy our country, so we need to do everything in our power to create very sophisticated, powerful weapons to protect our country.”

Once you have that premise, all the other stuff follows. It’s scary. We’re entering a timeline when that type of logic ends up having a weight it hasn’t really had for the past thirty years.

Jason Matheny: The risks of biological weapons being used intentionally or accidentally is increasing. We’ve seen lab accidents and biological weapons labs before that were close calls.

The 1979 Sverdlovsk anthrax leak was a close call. It was anthrax rather than smallpox. But the Soviet Union was developing smallpox that was resistant to vaccines and antivirals.

There’s lots of nastiness, unfortunately, in biological weapons programs that exist today — in labs that exist today that are making these sorts of weapons.

We underestimate the risk of either a lab accident or a miscalculation by either a desperate leader — maybe an autocrat who’s getting bad advice — or by an insider within a lab who decides to use this pathogen because of some nationalist fervor.

It’s a place within the security landscape that is just filled with risk.

Below is the final section of our interview, where we get into:

Why policymakers need more Tetlockian knowledge on human judgment and decision-making.

The upsides and downsides to tech moonshots, and why OpenAI leads the pack.

Jason’s White House years, and his takeaways on the non-stop S&T policy-making.

How art informs our thinking on tech and public policy.

The Science of Policy

Jordan Schneider: Past ChinaTalk guest Dan Spokojny of fp21 gets really frustrated when folks in government say foreign policy is an art, not a science. How can we get more scientific approaches into national security and technological decision-making?

Jason Matheny: For me, it was just exposure to the work in judgment and decision-making that had been done over the last forty or so years.

There’s just such a wealth of knowledge that we’ve generated over that time period about how human beings actually make decisions, what influences their judgments, and the kinds of practices that can lead to better judgments and better decisions.

Very little of that research has actually penetrated public policy decision-making.

I don’t know quite how to explain it. You would think that policymakers might be incentivized to make better decisions and that then they would use whatever empirical findings we had on how to make better decisions.

But there aren’t necessarily super strong incentives for improving our decision-making processes. We see the same kinds of failures in businesses that even have very strong financial incentives to make better decisions. Yet they also are not adopting some of the lessons learned from research on human judgment.

I asked Phil Tetlock and Barbara Mellers this question recently. They just pointed out that, in many cases, the incentives are not aligned for individual managers to make decisions that are objectively better.

Instead, they might be motivated to make decisions that appear better or safer, in some ways, to whoever determines their salaries or their professional futures. They’re thinking about something they can defend to a board of directors.

Jason Matheny: If you say to a board of directors, “Hey, I want more of our decisions to be made on the basis of betting markets, pre-mortem analyses, and crux maps,” the board of directors might be pretty mystified by all that. It’s not clear that they would necessarily want to endorse it.

There is just generally a challenge in overcoming the lack of awareness of some of these methods that test strongly when we evaluate them.

There’s also a challenge in that some of the highest-stakes decisions that we make in policy are not necessarily ones that have strong incentives for making the right decision or an accurate judgment.

I’m really interested in this. What does Moneyball for policy look like? How do we use science to help us make better judgments and better decisions?

We have spent a lot of time in cognitive psychology studying how humans actually make decisions under time pressure and under uncertainty. We know a lot more today than we did fifty years ago about this topic.

Let’s start using some of what we’ve learned. Let’s actually see whether these methods that appear to work well in other contexts can help us in policymaking.

Giant Steps Are What We Take

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about moonshot projects. Can the government do these anymore? Should they? How can RAND help build or rebuild that institutional capacity?

Jason Matheny:

We still do moonshots. A project like the F-22 cost more than the Apollo program. We still have these mega-projects or giga-projects. Maybe all told, some of the particular defense programs are terra-projects.

The value of moonshots, however, depends on a few things.

A moonshot in the wrong direction can be worse than a small project in the right direction. Small projects tend to allow more rapid error correction or course correction.

There’s increasing evidence that we underestimate the risks and overestimate the benefits of gain-of-function research. You wouldn’t necessarily want a moonshot for gain-of-function research.

A moonshot for AI capability might also end up being a net negative if you don’t already have a deep foundation in AI security and AI safety.

I agree with Richard Danzig who had a great paper called “Technology Roulette.” One insight from that paper is you want to make sure that you’re considering the risks of the technologies that you create.

You don’t want to jump too far in the direction of developing a technology that’s going to create asymmetric risk for yourself. You might want to focus on defensive technologies or ones that asymmetrically favor defense or safety.

You can think about differential technology development that’s focused on embedding safety and security from the start. We do need significant investments in things like as safety, biosecurity, lab security, judgment, and decision-making.

Some of those might deserve moonshots, but I’d even be happy with something even getting us to low Earth orbit on some of those topics even before getting to the moon.

OpenAI as Moonshot

Jordan Schneider: OpenAI, it’s fair to say, might be the most successful moonshot project we’ve seen over the past few decades.

What has made them so successful? What are your hopes and fears as OpenAI and other labs, both in the US and China, continue to explore AI’s capabilities?

Jason Matheny: OpenAI did a really admirable job with a lot of safety testing and red teaming. They published this thing they called the “system card,” alongside their main GPT-4 paper, that documented their safety and security work.

I’ve overall been impressed by the analysis they do on safety and security risks. Sam Altman, Miles Brundage, Jade Leung, and others on the team have been really thoughtful.

It’s also an interesting organizational design. You’ve got around 500 employees at OpenAI and it’s able to leverage the computing infrastructure at Microsoft. It links back up to what we were talking about earlier.

Sometimes when you’ve got a mid-sized organization able to leverage the infrastructure of a much larger organization, there can be some real benefits.

OpenAI didn’t need to spend a lot of time building its own computing infrastructure. It could leverage that elsewhere. That’s a big part of what makes these large language models practical now.

The F-22 Raptor as R&D moonshot.

The White House Years

Jordan Schneider: What did you learn from your experience in the White House, both at the National Security Council and the Office of Science and Technology Policy?

Jason Matheny: The people I worked with were some of the smartest, hardest working, most compassionate people I’ve ever worked with. The human capital there is phenomenal.

There are a few challenges working in the White House. One of them is the tyranny of the immediate. There are lots of urgent problems. Some are both urgent and important, and some are just urgent.

The Eisenhower matrix of urgent and important is really something we felt acutely all the time. We know there’s a problem that’s even more important, but carving out the time to work on it can be really challenging.

If you look at the amount of time spent in different policy processes as a proportion of the total, the fractions would not align with what you might think of as being the most important problems for the country to tackle. And it’s not because the people at the White House think, “Oh, well, the things that we’re spending the most time on are the most important.” It’s just that there are timelines for each of these.

If the President has a meeting with the ambassador from country X — even if country X is maybe not the most important thing that’s going to affect the United States in the next fifty years — he’s still got to have that meeting and you’ve got to prep him for it. A lot of that kind of timing influences how attention is budgeted in the White House.

I’d read about this in histories of the National Security Council, but I hadn’t appreciated it. It’s a really hard thing to figure out how to balance.

There have been various calls for restructuring the National Security Council so that it has a warning function and can do longer-range analysis. It’s just really hard to do that within the White House because there’s so many other time pressures.

I worked in both the National Security Council and in the Office of Science Technology Policy. OSTP had the luxury of being able to work on longer-range analysis. OSTP had sufficient room for analysis on things like supply chains or moves and counter-moves in technology competition. We could think a lot about AI safety and biosecurity on longer timelines than we typically would in the NSC.

Finding ways to leverage other parts of the White House — those that are able to have a little bit more room to think — is helpful.

I also think there are some problems that are likely to be thousands, maybe even millions of times more important than others.

I used to work on this thing called the Disease Control Priorities Project about twenty years ago when I worked in global health. One insight from that is there are interventions that are 10,000 times more cost-effective than other interventions. Malaria bed nets can be 10,000 times more cost-effective than building a new hospital in the middle of Egypt.

We don’t often appreciate just how cost-effective something can be. Doing the math to get even a rough order of magnitude for the consequence of policy decisions is something we don’t often do. But we could do more of it.

Another thing is incorporating more insights from people like Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Phil Tetlock, and Barbara Meller on human judgment decision-making and using these in the policy process itself.

We don’t do much pre-mortem analysis. We don’t do much adversarial collaboration, which is a really interesting approach to settling certain kinds of disagreement. We don’t do crux maps. We tend not to use probabilities.

A lot of the policy process could probably be improved if we used a little bit more of what we’ve learned from judgment and decision-making research over the last few decades.

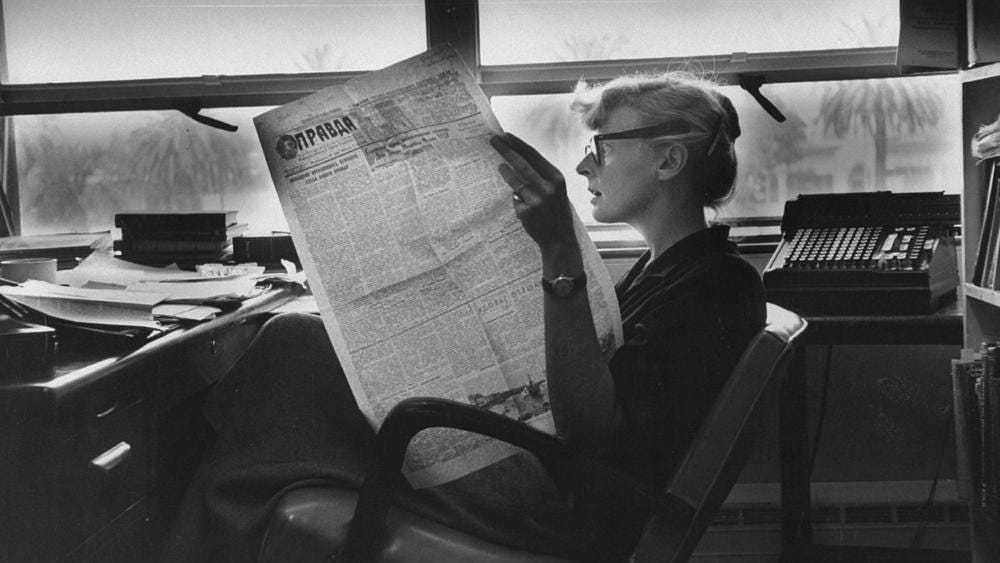

We need more red team analysis. Picture having a group whose permanent responsibility is to imagine how China would react to certain kinds of policies. Have that group thoroughly embedded in Xi Jinping’s thoughts.

It would be living day in and day out immersed in PRC media, doing its best to simulate the Politburo’s thinking. That’s probably really useful. It’s at least worth testing. Running these kinds of experiments on analytic and policy processes would be worth trying at least.

Jordan Schneider: I assume you were involved in one of the more consequential decisions of this first term of the Biden administration — the October 7 export controls on China. That must have been an enormous institutional lift to form that policy.

Jason Matheny: [We were] doing the analysis in a really detailed way — really understanding moves and counter-moves, costs and benefits. [We had] a team that was really deep on the technical details of chips — what they can do, what thresholds matter, how they could be used in the future.

[We had] enough technical expertise — both within government and from the national labs and elsewhere — that can help advise on that.

We were fortunate too in that some of the work had been done for us at CSET and other think tanks in advance. It’s really hard to do a lot of the thinking while you’re in the White House because there are so many demands on your time.

One of the advantages of places like RAND and CSET is that you sort of have the luxury of being able to do the math and work out the analysis. We were able to draw on that.

The other big lesson was that something like that doesn’t pass unless a significant number of departments and department heads agree with the approach.

So, that policy process was very inclusive. It involved a lot of agency heads. Their agencies reached the same conclusion for the same reasons on why the controls were warranted.

Semiconductors are pretty unusual in that they’re a real choke point with wide and deep moats in the global supply chain. They’re incredibly consequential for so many strategic issues.

In thinking about China’s ambitions in military modernization, cyber operations, and human rights abuses, chips play a major role in all three of those categories.

Old Executive Office Building in Washington, DC | The Thinking Insomniac

The Art of Policy

Jordan Schneider: You were an art history major? How did that come about?

Jason Matheny: I wanted to be an architect, and I went to a college that didn’t have an architecture school. I realized I wanted to be an architect after I had already started college. I worked as a social worker in Cabrini-Green, a housing project in Chicago.

As a social worker, I saw that building design can really impact the health, happiness, and security of families. I just wanted to design better public housing, social housing, or affordable housing.

Because the University of Chicago didn’t have an architecture program, art history was the way I could write a thesis on the history of social housing. Then I went to architecture school for a year.

In the library, I saw an orphaned copy of the “World Development Report” from the World Bank. It was the 1993 report, and it included these tables of statistics on preventable deaths due to infectious diseases.

I had never really had any exposure to that — just the millions of deaths caused each year that were completely preventable, especially childhood deaths. I was stunned. I couldn’t believe that these tables were right.

I asked some epidemiologists, “Is this true, really?” They were like, “Yeah, how did you not know about these basic facts about the world? We have about 4 million plus deaths for children under five due to these preventable diseases?”

Then I moved to start working in public health and infectious disease control and worked on that for several years.

Jordan Schneider: So, how did you end up working in defense and intelligence?

Jason Matheny: What brought me to national security was that in 2002, I was working in India on a global health project on malaria and tuberculosis and HIV. While I was working there, a DARPA project synthesized a virus from scratch just to see if it could be done.

That was an “oh, crap” moment for the public health community. It brought into focus that pathogens could be developed and could be much worse than existing pathogens. A virus that we had eradicated and controlled, like smallpox, could be recreated.

Some of the people I was working with in India were veterans of the smallpox eradication campaign. They were like, “Oh, man. Some sophisticated misanthrope is just going to recreate the smallpox virus. We’re going to have to go through this all over again.” That’s what shifted me to work in national security.

I cold-called Andy Marshall because he was the only person I really knew from the national security world. I had read a couple of these papers in college about RAND and its early work. I wrote every Andrew “something” Marshall at pentagon.mil.

I wrote twenty-six of those variants. Four or five wrote back, and one of them was Andy W. Marshall. I lucked out, and he encouraged me to come talk about the future of bio risks and other risks. That got me started in national security.

Jordan Schneider: Could you make the case for going to an art museum?

Jason Matheny: Have you been talking to Richard Danzig? When I was at IARPA — and he offered the same thing to DARPA — he’d say, “Why don’t we go on a tour of an art museum, and we can just point out the connections between depictions of technology and art — how it was viewed in its time and how we think about technology today.”

Art is a set of artifacts we can use to understand how society has changed.

It’s not a perfect sample. Only a tiny percentage of people are responsible for producing the art that sits in museums today. Only a tiny percentage of people were even able to see much of the art that exists in museums today.

But it is one instrument we have for recording how people valued different things within society over different periods. Taking an art tour with Richard Danzig should probably be on all of our itineraries.

The other case to be made is that you use a different part of your brain, so you can give some parts of your brain a rest. I spend an awful lot of time thinking about and working on depressing topics.

When I want to take a break, I often will walk down to the Hirschorn or the National Gallery and just try not to think about nuclear war or pathogens or cyberattacks and just think about these beautiful pieces of art around me just to put myself to rest for a bit.

I hope everybody has something like that that they can use to activate a different part of their brain.

Jordan Schneider: In another interview of yours, you were talking to a group of young people and told them that they should start working on catastrophic risk as soon as they could, because you wasted ten years of my life not working on catastrophic risk.

But look at you. You had all this runway ahead of you. The conversation we just had on organizational design and incentives, that ties into your early interest in designing better public housing.

I would not encourage everyone to have a laser-focused optimization function on whatever they think is the most impactful thing they can do today.

There's a lot of uncertainty. There's a lot you don't know as a young person. Bringing different perspectives to these important questions is the way we’ll probably end up having the most differentiated impact.

So, here’s my final question and maybe a suggestion. For your six-month pausing of the world, I'd love to see you pick up that drafting pen and redesign the White House and EEOB to help with better decision making.

I want to see what blueprints you have planned for the 2070 renovation!

Jason Matheny: Great. Okay, I'll get to work on an outline.