MP Materials, Intel, and Sovereign Wealth Funds

Addressing the rare earths challenge

We have a ChinaTalk meetup this coming Thursday in SF. Sign up here if you can make it!

Uncle Sam is taking a bite out of companies left and right. Today, we’re going to focus on MP Materials — the Trump administration’s answer to China’s restrictions on rare earth material exports to America.

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Daleep Singh, former Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economics, now with PGIN; Arnab Datta, currently at Employ America and IFP; and Peter Harrell, former Biden official and host of the excellent new Security Economics podcast.

Today, our conversation covers:

How China achieved rare earth dominance,

The history of rare earth mining and refinement in the US,

What the MP Materials and Intel deals do, and whether they can succeed,

The key ingredients for successful industrial policy and imagining a sovereign wealth fund.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app.

Broken Markets

Jordan Schneider: Why do deals like MP Materials even need to happen in the first place?

Daleep Singh: Critical minerals markets are broken for three main reasons.

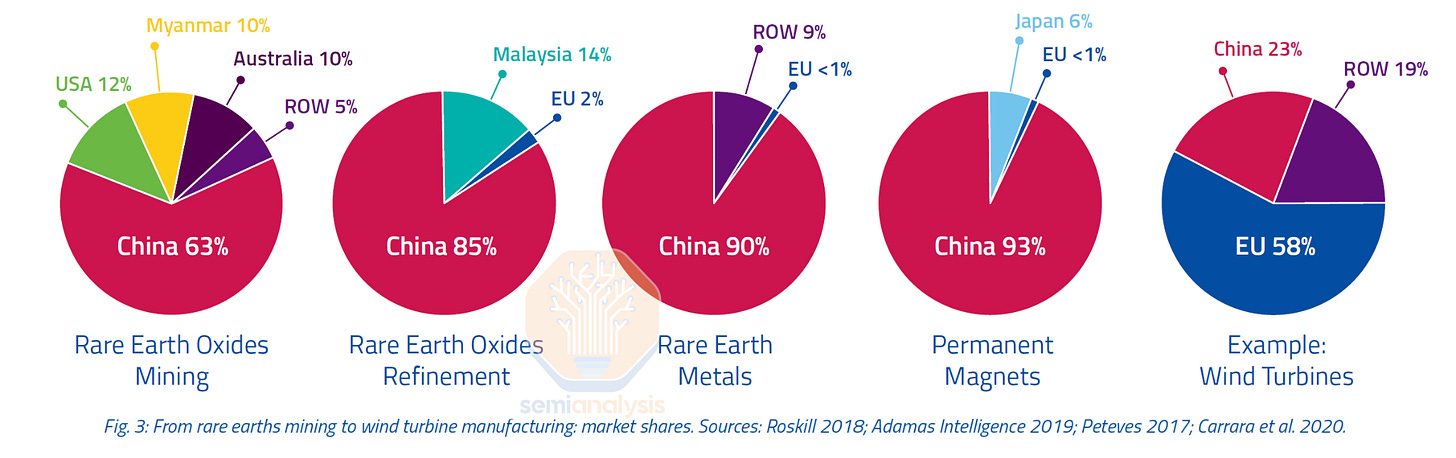

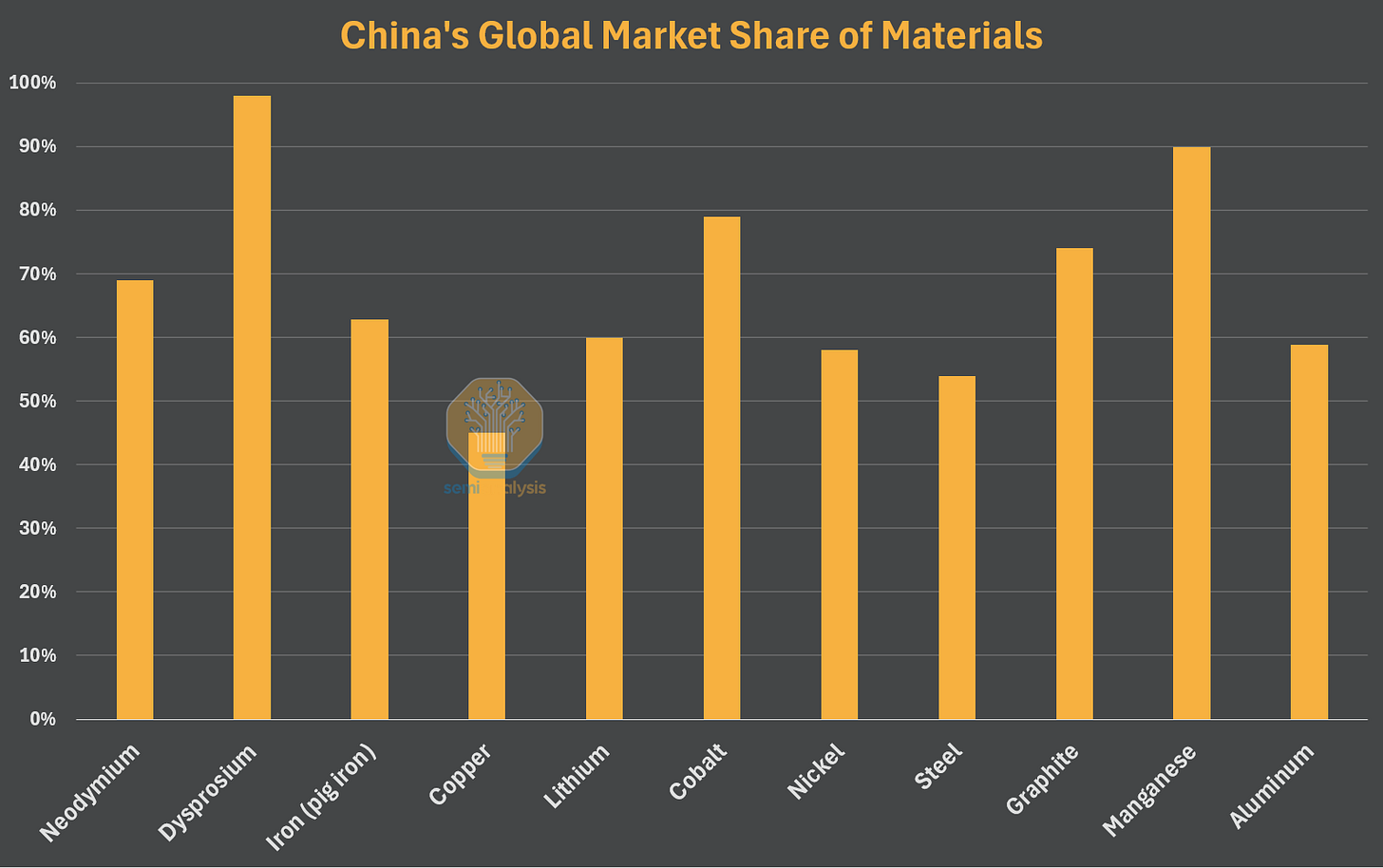

First, there’s concentrated market power. China refines 70 to 90% of most minerals that we need to power clean energy, digital infrastructure, and defense systems. They have enormous market power — not just over supply, but also pricing, standards, and logistics. No market can be resilient if one player dominates the entire market ecosystem.

Second, there’s extreme price volatility. Prices for minerals like lithium, nickel, or rare earths swing far more violently than oil and gas. For producers, this creates asymmetric risk — if you undersupply the market, you may lose some profit. If you oversupply, you may go bust. That asymmetry deters the investment we need to expand supply when quantities are low and prices are high, preventing the market from clearing.

The third problem is that we don’t really have market infrastructure for critical minerals. For oil, we have futures exchanges, benchmark prices, and deep liquidity. For most critical minerals, we don’t. Transactions are opaque, bilateral, and heavily distorted by state intervention, especially China’s. Markets don’t provide price discovery, and producers and consumers don’t have hedging tools. Investors lose confidence in these markets and walk away.

All together, we have chronic underinvestment, chronic gaps between supply and demand, and chronic vulnerability to geopolitical shocks. Those are the problems.

Jordan Schneider: Daleep, let’s dig deeper into the market infrastructure piece. What does this mean in practice — that it’s not like WTI, Brent, or something similar?

Daleep Singh: If you’re a producer, you need tools to manage price volatility. When prices fall dramatically, you need the ability to continue generating revenue to stay liquid. You need futures markets and option markets that you can use to hedge against downside price risk. Right now, if you’re a critical minerals producer for most of the minerals that matter for our economic security, you don’t have that option.

You also need price discovery — to know where prices are in the market. We really don’t have genuine price discovery from any of these markets. China can decide, just by virtue of its dominance in supply, where it wants the price to settle. If it wants that price to settle at a level that wipes out the competition, that’s its choice. That’s not a market.

Arnab Datta: One quick piece to add is that the market infrastructure problem Daleep mentioned was really an intentional strategy by China. In addition to very robust industrial policy that provided substantial subsidies to producers and refiners, they stepped into the market infrastructure gap that was retreating in the West, particularly after the global financial crisis.

When you saw liquidity leave Western markets partly because of regulations passed during that time, China seized the opportunity. They built exchanges and benchmark contracts on Chinese exchanges so they could control that market infrastructure and how these prices were constructed.

Peter Harrell: I’d add two important pieces.

First, America’s dependence on China for rare earths is actually a relatively new problem. Historically, going back several decades, the US actually produced, mined, refined, processed, and manufactured plenty of rare earths in the 1950s, 1960s, really through the 1980s and into the 1990s.

It was in the 90s and 2000s — the era of peak globalization — where China successfully expanded its rare earth refining in particular. You saw Chinese firms begin to outcompete American firms, and a real decline in US manufacturing related to this consolidation of Chinese control. This isn’t because the US never made rare earths. This is really a problem of economics that emerged in the 90s and 2000s.

Second, we saw just a couple of months ago the critical risk that dependency on China for rare earths gives us, because it became part of the trade war Trump launched with China. Back in April, China retaliated by threatening to — and then actually — cutting off its exports of rare earths to the US, which had the potential to really impact manufacturing here. It became much less of a hypothetical long-term risk and much more of an immediate threat that could actually hurt the United States in the near term because of how China responded to Trump’s trade war in April.

Arnab Datta: Just to add to the WTI comparison — if you think about how WTI is priced, it’s a physically cleared contract. You’re purchasing a barrel that will be delivered at Cushing, Oklahoma. The pricing incorporates pipeline transport, logistics, and a whole infrastructure of traders, logistics providers, and port managers — all of that goes into the price of that physically delivered barrel at Cushing.

That’s something we just don’t have in the context of many of these newer metals markets. It’s very difficult to properly price a material when the only analog you have is a Chinese benchmark that potentially has very different constraints and very different characteristics.

Strategic Resilience Reserve

Jordan Schneider: This became very acute a few months ago when Trump imposed tariffs. Something that people have been talking about in Washington for literally 20 years — China using its role in the global rare earth export market to punish countries for doing things they don’t want — finally manifested. Trump walked back, and now we have this as a central thing that China and the US are tussling over.

Peter, Daleep, you guys aren’t dumb. You knew this was an issue. People have been writing about this for a very long time. What is the activation energy required in the 21st century to do the kind of industrial policy necessary to really change the dynamics on an issue like rare earths? Why have we only seen small, half-formed efforts until spring and summer 2025?

We have a Washington that has talked about the problem for a very long time now starting to spend nine and ten figures to address it in a more direct way than the incremental efforts folks had been pursuing. Peter, talk us through this deal. What came out of the Trump administration and the DoD over the past few weeks?

Peter Harrell: As you said, this isn’t a new problem. Policymakers have been aware for more than a decade that there was US dependency on China for rare earths. The Chinese had cut off their exports of rare earths to Japan back in 2011 or 2012. We’d actually seen the Chinese execute this playbook once before on an allied country.

This isn’t a new problem, and it’s not that there were no efforts to deal with this issue prior to the deal that the Defense Department announced in July. There were some efforts — previous grants, including to MP (the company that got the deal in July) to try to restart manufacturing and processing of rare earths in California where there’d been a longtime US mine. Actually, the mine had reopened in 2017.

There had also been some grants to other companies and universities to look at other ways of mining and processing rare earths — for example, to extract them from mine tailings in West Virginia. There had been some government money to try to sponsor innovation to reduce dependencies on rare earths, maybe create magnets and other products that you need rare earths for but without actually needing the rare earth elements.

There had been some policy processes and policy money put into trying to address this problem. But there were a couple of challenges with those prior efforts. First is just the scale of the effort. Frankly, the way Washington works, until there is a very acute crisis, it can be hard to mobilize the scale of effort that is actually needed to solve it. These prior efforts were much smaller in dollar spend and scope because the crisis seemed less acute. That’s just a political reality of how Washington works.

Second, this is a very complex issue. I don’t even think this new DoD deal with MP is going to be the whole solution. It’s going to require several parts. It is, in fact, a very complex issue.

Third, related to mobilization: solving a problem like this is going to cost money. You get into big debates about who should pay for it — should US taxpayers come up with the money, or should you make the private sector bear these costs? That adds to why it takes time. It’s not that there was nothing — there was some foundation that this deal is now building on. Not that there was nothing before, but Daleep, I’d welcome you defending our work together in the Biden administration.

Daleep Singh: Jordan, I appreciate you suggesting that we’re not dumb. That’s nice — we don’t always get that. But look, there have been piecemeal efforts to funnel public money toward private sector companies that could help produce minerals we need. What we haven’t done is fix the market. That’s where we are now.

I started thinking about reimagining the Strategic Petroleum Reserve into a Strategic Resilience Reserve for 21st-century vulnerabilities.

When prices crash and China continues to flood the market, we have this recurring problem of producers going bankrupt.

A Strategic Resilience Reserve could be a buyer of last resort or provide bridge financing to companies that are solvent but illiquid. That’s what could allow producers to keep producing during downturns and keep production capacity alive.

What can we do about investors not having confidence in these markets? If you don’t have futures markets and hedging markets, and refiners can’t lock in predictable revenues, could a Strategic Resilience Reserve step in with tools like selling a put option that allows you to make money when prices fall? Could it provide a price floor or some type of demand guarantee? The point is: can you create enough certainty for private capital to keep flowing?

What do you do about concentration risk? Even with a deal like MP, no country is going to mine its way to self-sufficiency when we’re up against what China has. But we do have producers and miners in places like Canada, Australia, and Finland. They’re hesitating to expand production because they know China can tank prices tomorrow.

An SRR, if we got that authorized, could provide demand backstops and offtake agreements. Could it intervene in the market so that producers in allied countries know they’re not going to go bankrupt if Beijing floods the market? That’s the idea we’ve started to develop over time — probably with some mistakes — to change the market itself rather than a series of ad hoc transactions that don’t alter the economics.

Jordan Schneider: SRR — a Strategic Resilience Reserve — a topic we’ll get to in a few moments. I’d also like to say in defense of the last 20 years of American policymaking that this was a latent threat, and the trajectory of US-China relations that made this become an actual threat has manifested relatively recently.

The fact that the Biden administration was able to “get away” with imposing semiconductor export controls, implementing big tariffs, essentially banning Chinese electric vehicles, and a handful of other tariffs without triggering this response is important to recognize. This is only a problem in the context of the US-China diplomatic relationship. Without that relationship souring, then we just get to use some subsidized magnets and the world moves on.

Peter, what was your thinking about trying to inch forward with more and more aggressive economic tools while seeing things bubbling up in terms of new Chinese legislation but not wanting them to hit back for the efforts you were making?

Peter Harrell: When I think about how one can solve a problem like our dependency on China for rare earth elements — and then we can unpack what this deal will and will not do — you need to think about several different categories of policy tools that you need to mesh together to solve the problem.

We’ve had this history in American industrial policy over the past decades where we’ve focused almost exclusively on what you might think of as supply-side industrial policy. We’ve given grants to companies to build a factory or a mine to do something. In some cases, that can be sufficient because the problem we need to solve is one of startup costs. It costs more to get something off the ground in the United States, and you can provide a capex incentive to help get it off the ground.

But when you look at China’s dominance of rare earths — where they not only have already spent a lot of capex, but their operating expenses are lower than in the United States and they control the market infrastructure — if you want to break China’s control here, you can’t solve it simply with our own capex.

You also need to think about the market infrastructure, as Daleep says, and you need to think about what the demand side looks like. If US operating costs for producing rare earths are going to be higher than they are in China, you have to find some demand for that higher-cost US product. Otherwise, US companies are going to keep buying Chinese products because the Chinese products are going to be cheaper.

You need to create a market infrastructure that’s going to ensure stable demand for the US-made product. Layering these things together — these different sets of policy tools to address the different parts of the chain — is not something the US government has done in a long time. You have to get your reps in and spend some time in the gym before you can do it.

Daleep Singh: Peter and I used to sit in the part of the White House that was straddling economics and national security. For most of us, very early on in the term we understood — especially as Russia’s forces were mounting on Ukraine’s border — that we’re going to be in this incredibly contested geopolitical environment for the rest of our lives. China and Russia have now made it very clear and revealed they’re going to challenge the US-led order everywhere. Because today’s great powers are nuclear powers, our expectation became that this competition is going to play out mostly in the theater of economics, energy, and technology.

The question was, if we’re going to prevail, how can we harness the financial firepower of the world’s most dynamic financial system to advance strategic objectives? Do we have the right tools, do we have the right institutions to overcome this short-term profit motive that drives most of what’s going on on Wall Street? The answer is no. As time went on and we started to have time to breathe, we started to think about new ideas. That’s where the Strategic Resilience Reserve came up. We also started to think about whether the US should have a sovereign wealth fund. These are all ideas trying to solve the same problem: the private sector systematically underinvests in exactly the kind of projects that matter most for our economic security and for our national security.

Can the Deal Create a Market?

Jordan Schneider: What does this MP Materials deal do? What is interesting and exciting about it? And why is it not the systemic solution that Daleep craves to manifest?

Arnab Datta: One thing this deal does is treat the problem holistically. Peter mentioned that you need a mix of supply and demand side tools. The administration deserves credit for using the DPA, the Defense Production Act, in a robust way. They are applying a toolkit that includes loans, equity investments, price floors, and a guaranteed contract for offtake for the finished product. That’s just a recognition. Ultimately, if we’re going to deal with this problem over the next one year, five year, ten year, decades, we need a robust toolkit and we need a mechanism by which we can address these very challenges.

Jordan Schneider: Arnab, briefly, who did this? This is very sophisticated, impressive work. It’s a lot of puzzle pieces which haven’t been put together in a very long time.

Arnab Datta: It was done through the Defense Department. It pairs a number of different authorities. I would say the most creative, atypical interventions were through the Defense Production Act — this is Title 3 of the Defense Production Act. It has very wide authority attached to it. Peter did a recent piece in Lawfare examining this, but it basically allows you to engage in a number of different transaction types to achieve the goal of building our defense industrial base. There’s also some capital from the Office of Strategic Capital. That’s where the loan is coming from.

One thing to keep in mind is that some of these appropriations are not spoken for. Over time you could imagine funding coming from different parts of DoD from the national defense stockpile. They’re going into this with the commitment and a very clear interest and effort in continuing with this deal. But there are some risks and there’s also some structural challenges with this deal that I’d be happy to go into as well.

Jordan Schneider: Peter, give us the flip side. What doesn’t this accomplish and solve?

Peter Harrell: Let’s first walk through what this deal is, because there was some news last month when it came out. I think a lot of the news focused on the fact that the Defense Department, as a piece of this deal, was taking equity in MP Materials, which now looks like a precursor for the Trump administration going out and taking equity in Intel and maybe a whole bunch of defense companies and everything else. I think that was the piece that attracted the news. But the deal is a fairly complicated deal that has a couple of different parts.

Part one of the deal is the government gave MP Materials, this mining company, some loans and then some cash as part of the equity stake to expand its mine in California, not that far from Las Vegas — Las Vegas is the nearest big airport to this mine, but it’s in California. To expand production at the mine and then relatedly to expand and build a new facility to take some of the rare earths being produced in this mine and to manufacture them into magnets, because what we need is not raw rare earths. What you need are magnets that go into motors and turbines and all kinds of other things. There’s almost no magnet manufacturing in the US and in fact, previously this mine had been producing rare earth ore and then selling it to China to be made into magnets there.

Part of this is a capital injection to MP to expand the mine and to build some magnet processing — expand some magnet manufacturing capability here in the United States. They’re doing that with both a debt and equity stake.

Another part of this deal is the Defense Department set a price floor for the raw rare earths, where the Defense Department has guaranteed that when MP is mining and doing initial processing for the raw rare earths, it now has a guaranteed minimum price, which by the way, is about twice what the current Chinese market price is.

That’s how you guarantee that it’s economical for MP to make this stuff over the next ten years. Because DoD said, “Even if the market price is $54,” which is about what I think it is today, “We’re going to guarantee a price of $110 per kilogram. We’ll pay you the difference between $54 and $110 per kilogram.” You have this price floor for the minimally processed rare earths. Then on the magnet side, DoD also said, “We’ll buy all of your magnets. You can produce these magnets for the next ten years, and we’ll buy all of them.”

There are some interesting pieces, such as if DoD and MP jointly agree that some of the magnets can be sold to buyers other than DoD, then there will be some profit sharing and other provisions. But it’s actually a pretty complicated deal with interrelated parts, which very clearly does ensure the viable business for the next decade of MP. MP gets capital injection. MP gets a guaranteed price floor for its rare earths concentrates — minimally processed rare earths. And then MP has a guaranteed buyer for its magnet.

MP is taken care of for the next decade and will be able to scale up production of both the minimally processed rare earths and probably of magnets.

But that doesn’t mean we have a market here. What we have is a market for MP.

That’s where I think there’s some interesting questions about this deal. Are we right to bet all in on MP as a national champion, or should we be thinking more systemically about the markets and less about how we guarantee the success of this particular firm? Arnab, I know you have a lot of thoughts on that piece of it.

Arnab Datta: We have a forthcoming article on the topic. We’re hoping to get it into Alphaville there, but they’re working it up the chain. We’re not fully signed off.

Jordan Schneider: In this piece, Peter and Arnab, you point out that this is similar to Chinese industrial policy circa Mao era, not the version 2.0. You’re picking one winner. And by the way, this company is probably not the best managed company in the world, as opposed to the way that China does it, where you have lots of firms fight it out to be the top dog.

Once you whittle it down to not one, but five or seven, then you start really turning on the jets and pouring on the money to secure your position in the global marketplace. As Daleep alluded to, this is also a concern with Intel.

For what it’s worth, I do think that manufacturing at the leading edge probably doesn’t support as many entrants as opposed to just building some mines and making some batteries. But, there does seem to be some tricky incentives and a lot of risk that their head of mining doesn’t go to a Coldplay concert with their head of HR or something. Daleep, where are you on this as an approach?

Daleep Singh: It makes me think of Intel a lot and I realize that we’re talking about very different markets, but I have the same take on it. Let’s actually pivot for a moment to Intel. There definitely needs to be government intervention in both of these markets. With leading edge semiconductors, we don’t produce any of them. Intel’s the only US firm capable of making them. But it has no customers and without customers, Intel can’t scale its unit cost efficiency — remains low and its competitiveness lags. Market forces aren’t going to solve that problem, nor will it solve the problem for MP.

But what gets interesting is instrument choice. What I worry about is ad hoc improvisation about what tools of industrial policy to use for particular sectors with a different context and a different kind of problem to solve. What I come back to is the systematic stuff. We do need a playbook, a governance structure, a doctrine for industrial policy. Start with the strategic objective. What problem are we trying to solve? Whether it’s MP or Intel or any other company, what is the market failure? Is it a shortfall of demand? Is it a capital constraint? Is it a cost differential? Is there a coordination problem? Is there some national security externality?

Then the third step is: pick the policy instrument that remedies the failure. Don’t default to equity injections or subsidies if the problem is demand, for example. Can you actually intervene? This goes to Peter’s analysis on MP. Does the intervention sustain competition and does it avoid a single point of failure? I would try to avoid substituting a foreign monopoly for a domestic point of failure. Can you tie the support to milestones, objective milestones, so that you can claw back the support you’re giving from taxpayers if they underperform? Can you sunset the support to avoid permanent dependence?

The last thing is how are you measuring the strategic return? What is the metric for success with this deal? It can’t just be for financial gain. How are we going to measure the benefit in terms of resilience, security, technological edge? That’s what’s missing for me. Maybe it’s out there somewhere, I just haven’t heard it.

Arnab Datta: I’d add to that a couple of things. This is a national champion that’s crowned without contest. We do have a pretty robust, vigorous competitive process folding out right now in the magnets space. There are other companies. MP Materials has the Mountain Pass Mine, but it has never produced a commercial magnet. It has not sold a rare earth magnet at commercial scale. When you think about the challenges that go into selling commercially — automotive is a major purchaser of these magnets — you need to get your production facility warranted. That’s a long process. There’s no sense right now — we don’t know they could get warranted for automotive. They might not. It’s a very challenging process.

We do have competitors that are innovating. There’s a company, Niron Magnetics, that’s based out of Minnesota, they’ve produced a rare earthless magnet. This is the best of America in my opinion. You’re innovating yourself out of this vulnerability. I don’t know if Niron can scale at this point to the commercial scale that we need. But I also don’t know about MP Materials. When you start to get into some of these policy questions about is this intervention in this single company the right one, it raises a lot of secondary thorny issues.

This is a bet on vertical integration for rare earth magnets, that’s what they’re trying to build here. With MP Materials, that might be a good thing. A lot of the Chinese champions are vertically integrated, but there’s also a world where vertical integration on its own creates its own vulnerabilities. We see this a lot in the metals space where when we need to increase production because of some challenge, it’s not the vertically integrated producers that are responding quickly to price swings. It’s the marginal producers, the independent producers. This is something very common in metals markets. It’s something very common in the oil sector as well. These are really important policy questions.

My biggest concern globally with this deal is I don’t know what that reasoning is. It’s possible there are very well thought through reasons, but these are things that need to happen with some kind of a process that has technocratic democratic legitimacy to it. That’s why Daleep talking about the systemic solution is really important because we do need to make sure that these decisions are made in that context. I am not opposed to equity investments of all kinds. I think it’s an important tool for the government to have. It lets you push the risk frontier for your investments. If you’re a program, it lets you participate in the upside. But that needs to be done in a very thoughtful way. It’s a very powerful tool and we need to think about whether we are inculcating the things that make the American system dynamic — competition, innovation, technological innovation.

Daleep Singh: Can I ask Jordan, what is the exit strategy from the MP deal? Is it tied to production capacity or profits? How is the government going to sell down its public stake if at all?

Peter Harrell: The SEC filings talk about the government taking the stake. The government has also, in addition to the price floor, the guaranteed offtake agreement for the magnets. A belt and suspenders approach also guaranteed MP an annual profit of $140 million a year, which the government will pay as a cash payment if it’s not generated from the operations of the company. Presumably the government is intending to hold its equity for at least the ten year duration of the other elements of this deal. But there’s no specific language in the SEC filings about the government’s exit plan. It’s about the equity and then the duration of these other parts of the deal, which is a decade.

Arnab Datta: It’s structured as a ten year deal. I think ultimately the expectation is that the price floor and the offtake agreement will end at that point. But there’s no protection against the dependence. How do we stop this from becoming something that’s permanently dependent on this subsidy? It’s not clear.

It also doubles down on the Chinese market infrastructure. The benchmark that they are using is the Asian metals benchmark. That brings in the risk of manipulability too. China can bleed DoD for hundreds of millions more by flooding the market. How long is Congress expected to continue appropriations for that? These are not paid for. The one thing that was very clear in the 8-K is that they don’t have appropriations for all of this. How long can we expect Congress to keep paying? I think it is a very reasonable question as well.

Maximalist Industrial Policy

Jordan Schneider: I want to have this strategic question. What are reasonable goals over a three-year, five-year, or 10-year horizon when it comes to rare earths in particular. More broadly, what types of things would you want the Strategic Resilience Reserve to touch on?

Arnab Datta: There are a couple of key objectives that we’re trying to build here.

First, can we build a governance structure that is independent, technocratic and driven by market realities and not by political exigencies or other factors?

Second, can we build that robust toolkit that we talked about earlier for different markets? Rare earths we’ve talked about have particularly unique needs. They’re smaller than some of the bigger metals markets. We can’t be sure that you need a futures market for every rare earth that is on the market. But that’s a major goal as well.

Third, I would say the explicit purpose of what we’re trying to do here is build that competitive market. Are you supporting the buildout of a market infrastructure that is tied to market dynamics that US and allied producers face? Are we doing lending with intermediaries that can engage in more trading activity because they’ve got the leverage that left the market in the 2000s and 2010s, as I described? That’s an important piece of it because over five to ten years, if we can have a more stable market infrastructure for US and allied producers that reflects the costs they face, the logistical challenges they face, ultimately you’ll have a better stable foundation in place for those producers to compete.

Jordan Schneider: Beyond solving the market plumbing for things that would fall into strategic resilience, what is the big bold version of the systemic and thoughtful way to do the sorts of things that we’ve seen over the past few months with MP and Intel and we’ve seen over the past few years with the CHIPS Act and the IRA?

Daleep Singh: The maximalist version is a sovereign wealth fund. If you believe that the private sector systematically underinvests in projects that we need most for economic security and national security, then we’re not going to invest as a country at pace and scale to build fusion plants, dozens of semiconductor fabs, next-generation lithography, 6G telephony, or advanced geothermal. We’re also not going to invest enough in old economy sectors where we need to blunt a competitive disadvantage. Think about shipbuilding, or, lagging-edge chips, or mining.

What all of these projects share in common is that they require a lot of upfront capital and they require a decade or more of patience to generate a commercially attractive return. You need a huge tolerance for risk and uncertainty. The private sector venture investors, in particular, but also corporate America, are not likely to touch these in the size that we need them to because they’ve got plenty of other opportunities to make faster, higher, less risky returns. That’s why we have this valley of death right between breakthrough research and commercial scale.

I think the maximalist way to solve this problem is to create a flagship investment vehicle that gives the US patient, flexible capital, that can step in where markets won’t and that can crowd in private investment and back projects with genuine strategic value. That’s the case for a sovereign wealth fund. It’s not about picking winners, though. It’s about picking supply chains and technologies where our national security and our economic resilience are at stake.

It’s premised on the idea that left to itself, the US’ financial system is not designed to maximally align with our national interests. We need to intervene.

Jordan Schneider: I remember first reading you and Arnab’s piece on this a few years ago and thinking that was unlikely, but now Trump is into it. I wonder if it wasn’t called a golden share if he would have been as excited about this concept. But you do enough one-off ones and then you also learn that there are mistakes in the one-off ones and that you aren’t getting a systemic solution. It can go both ways. Either you give up on the project entirely or, given that the broader strategic purpose for these things keeps rearing its ugly head, you start to think in a larger and more systematic way at attacking these problems.

Let’s go level down. How are we funding this? What’s our governance structure? How’s the democratic involvement?

Daleep Singh: Whether you’re focusing on the MP deal or the 10% stake in Intel or the 15% revenue share from Nvidia or the golden share in Nippon, the point is we have a choice. Either we can improvise and experiment or we can develop a framework. Because I think the problem with improvisation is that if we just reach for different levers — an equity stake here, a profit share there, a golden share somewhere else — if we don’t have an overarching framework for why we’re using these tools and when and how and to what extent, I worry that this has the makings of a political piggy bank and a national embarrassment.

I understand some degree of experimentation is going to be needed. We haven’t done industrial policy in 40 years, and the muscles have atrophied. I get it, let’s take small steps and learn from those steps and then recalibrate. But I’m not in favor of ad hoc capitalism with American characteristics because that’s inevitably going to pick favorites and distort incentives.

You’re asking the right question. How do you govern a sovereign wealth fund or a Strategic Resilience Reserve the right way? How do you fund it? On the sovereign wealth fund idea, my thinking is we’re asset rich as a country. The federal government owns about 30% of the land. We have extensive energy and mineral rights. We own the electromagnetic spectrum. We have infrastructure assets all over the country. We’ve got 8,000 tons of gold that’s valued at 1934 prices. We’ve got $200 billion of basically money market assets that are sitting idle. The question is, are we maximizing the strategic bang for the buck on those assets? I would say no. That’s one potential source of funding.

You could also create new revenue streams to fund the vehicle. If you think that the US has too much Wall Street and not enough Main Street, that we financialize the economy into a series of boom-bust asset cycles, then let’s raise revenues from financial activities that serve no strategic purpose. I would say high frequency trading, for example, and fund vehicles that are explicitly designed to advance our national interests.

Jordan Schneider: As long as we stay away from fixed income.

Daleep Singh: Exactly. That’s untouchable. But the most appealing approach is the most straightforward one: ask Congress, be straight up about it. Ask Congress to seed the fund, authorize its existence as an independent federally chartered corporation authority. This is too important to leave entirely to the executive branch and have Congress set a clear mandate in terms of the objectives, the metrics for success, the oversight, the democratic accountability which Arnab was pointing at earlier. It’s a shame we didn’t do this ten years ago when our cost of capital was near zero. That would have made this effort far more affordable. But this is about our long-term national competitiveness. We don’t need to try to time the market.

Arnab Datta: One model that we think about a lot at Employ America is the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve has an independent board still, knock on wood. But that’s a structure that is well insulated from political day-to-day activities. It is not a 51-49 majority power structure. It has staggered terms, which, in my opinion, lends itself to depoliticization that’s helpful and has served us well over time.

In terms of the congressional point that Daleep made, we have had a version of this. We’ve worked with Senator Chris Coons’ office since 2020 on his proposal to establish an Industrial Finance Corporation. This is modeled off of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation that we had in the 30s, 40s, and 50s. We had then-Senator Vance on as a co-sponsor. I don't think the political viability of something like that is small. The way we structured that was we appropriated capital to it as a backstop against the borrowing that the corporation could do itself. This corporation could go out and raise capital by raising bond capital and then deploy that capital towards these investments that Daleep mentioned.

One value add about that is you don’t need to compete with the private sector on the rate of return, but you can generate a rate of return. Ultimately that type of a structure could pay for itself. There are a lot of technical accounting rules related to how you would structure that, particularly the Federal Credit Reform Act would come into play. But that is a structure that I think could be viable over time and we have the money to do it. Ultimately because a lot of these investments would be productive over 5, 10, 20 years, I think it would pay for itself.

The Right Tools for Intel

Jordan Schneider: I can’t let you guys leave without a few more Intel takes.

Arnab Datta: I’ve seen two separate conversations happening. One is on the legality of this and another on the policy justification. Peter did an excellent piece in Lawfare that came out a couple of days ago. This is possibly legal in a very technical sense, but does probably violate the spirit of the CHIPS Act in that the CHIPS Act is intended to incentivize manufacturing investments — they are giving this money to Intel but relinquishing most of those requirements. Earlier, we talked about milestones that companies should have to meet. Intel had a bunch of milestones attached to this money. They couldn’t get it all until they reached those milestones. They now have this capital, but they don’t have to meet those milestones. I think that’s a big problem.

Separate from the legality of the policy proposal here, why was this the best way, best thing for Intel? It’s not clear. As Daleep mentioned earlier, they need customers. An equity investment is not going to help them in that sense. For all I know, the share price could go down and our investment could go down because they can’t find customers. I think it’s a big problem that we’re not approaching the question of how can we make Intel more competitive? We seem to be approaching it in an ad hoc way — how can we get the best for our dollar in the form of a deal, an equity deal.

Daleep Singh: That’s my main concern — the right tools here. I agree with the intervention, but the right tools have to come from the demand side. Procurement guarantees, offtake agreements, sourcing mandates — all of those ideas make a lot of sense to me. It’s not clear how the equity injections fill the demand gap.

When you make upfront equity investments, you are foregoing optionality. I would have liked to see warrants or options that are tied to success. In general, I think policy support should be conditional. Conditional on whether you’re reducing unit costs or diversifying customers or hitting your production capacity targets. I do like the idea of clawbacks. The government has lost a lot of optionality with an upfront common equity injection. Maybe there’s a lot in the fine print that we don’t understand, but that’s what I found lacking.

Peter Harrell: I just echo what Daleep and Arnab said. The specifics of this deal are troubling. The idea of policy support, financial support to have onshoring of US semiconductors — clearly needed, clearly broad, bipartisan support. The idea that we shouldn’t be dependent on TSMC, the Taiwanese semiconductor firm for leading edge manufacturing, I think also has bipartisan and sensible policy support. You want to have some competition and some optionality at the leading edge of semiconductor manufacturing.

But what this deal did was take a grant in which Intel was getting $11 billion in exchange for Intel investing — call it $80 billion in fabs over the next decade. Intel was going to get the $11 billion in tranches as it built the fabs. If it failed to build the fabs, there was going to be a clawback. Now Intel is getting about $9 billion of the dollars in exchange for the stock. Plus they have to complete building certain DoD specialty lines.

Most of the obligations to build fabs went poof, and they got the cash in exchange for stocks.

I get why Intel might have done it. They get cash that’s largely unrestricted. They dilute their existing shareholders, but they probably decided the cash is worth it for us to do whatever we want with it. Reasonable call from Intel.

Arnab Datta: I’m also thinking about warrants. They’re using, in all likelihood, something called other transactions authority to legally justify the use of this deal. Other transactions authority is an incredible gift to the Commerce Department to be able to design very diverse mechanisms for policy here. In my opinion, wasting it on this equity investment that has little attached to it is a real mistake. They could put some effort into something creative that did go to the root of the problem about customers, and they’re squandering it, in my opinion.

Jordan Schneider: I think what you all said makes sense under a normal presidency living in the year of our Lord 2025. The way Intel survives is it gets customers, and the way it gets customers is Trump terrifies CEOs. If 10% of the company is what Trump can do to terrify CEOs, then all right, we’ll see. When we were talking earlier about MP Materials, it’s really not rocket science. You could have a beauty pageant with five different companies all trying to mine different places and have something. There’s one horse in this race and at a certain point you have to hope that they can execute as long as the demand’s there.

My sense and hope is that having a golden share owning 10% — Trump will care and be more invested and put more of his cycles and wrath into rounding up a handful of people who are going to spend the time to deal with Intel and help them get back on track. Regardless of whether it was warrants or a grant or equity, whether or not Intel is able to catch back up to TSMC is going to be a function of execution. And a president turning the screws on US fabless customer companies to play ball with Intel. The fact that Trump is caring about this and is focused on this, I would not have priced in completely from the get-go. He was literally talking about having to fire Pat Gelsinger — probably the only man who could, the person who I trust more than anyone else on the planet to actually execute this right who doesn’t work at TSMC currently. I’m more bullish on this than you guys are.

Arnab Datta: Can I offer one pushback on that, Jordan? One thing I would say is yes, there is a tremendous focusing mechanism — companies will, you saw this with MP where just a few days after the announcement Apple signed a big deal with them, a $500 million deal. The thing I would say is at some point the market has to trust that Trump’s commitment to this company will continue. President Trump is not going to be president forever. Intel is not going to be operating only on a four-year timeline. At some point Intel is going to require commitments from other companies and at some point they might turn and say this guy’s not going to be president anymore. We’ve got someone else to please here.

Certainly I take your bullish case. But Intel can’t survive only on that. They need an outside market and they need potentially capital from external sources down the line. At some point we’re going to be in a post-Trump world and it could look very different for Intel.

Great discussion. Must read the book “Elements of Power” by Danial Abraham to get detailed history of the situation. One key point that was left out of the discussion is that there is a giant shortage of mining engineers in the US. There is only one school of mining in the US with a high reputation… The Colorado school of Mines. You can have all the investment you want. If all the engineers want to do social media engineering and not get there hands dirty, then nothing substanial will happen.

All of this discussion and no mention of radioactive elements that occur with most, if not all, REE sources and what to do about that. Or the role that NRC plays in regulating extraction of REE when thorium, in particular, is 50% or more of production mix. Or the long story about our giveaway of thorium reactor tech to China on early days of WTO entry. Or, or, or. The lack of depth on minerals commodities is the biggest impediment to thinking and strategy in US and elsewhere.