Notes From Korea

beauty, food, massacres

Last month, Irene and Lily went to South Korea to report on a twin set of robotics conferences. Here are a few notes from their travels.

On Korean Beauty

Irene:

Hallyu — the “Korean Wave” of pop culture that began spreading internationally in the 2000s — taught my generation of Asian Americans/Canadians how to style ourselves. We grew up with few relatable points of reference in mainstream Western culture, as our physical features rarely aligned with American beauty standards. K-pop built an alternative, affordable framework during our coming-of-age, and it was impossible to miss its influence even if you (like me) never consumed much of the music or TV dramas.

Goryeo (the royal dynasty that ruled the Korean Peninsula from 918 to 1392) began sending women by the hundreds as tributary gifts to the Chinese empire during the Tang dynasty. The Middle Kingdom, from then on, routinely scoured the Peninsula for beauties. The third Ming emperor, Yongle, was recorded to have favored a concubine surnamed Kwon from Joseon (the dynasty that followed Goryeo). After Kwon died at the age of 20 in 1410, the Yongle Emperor sentenced perhaps thousands of women from his harem to death on suspicion of poisoning Kwon, according to one Korean chronicle.

Japan’s colonial rule forced between 50,000 and 200,000 Korean girls and women into sexual slavery as “comfort women” for the army. After the Second World War, another vast sex trade sprang up around American-led army bases across South Korea, with girls and women trafficked by their own government to provide “morale” to UN troops and bring in millions of foreign money for the economy.

Beauty remains one of Korea’s most prominent exports. Multilingual advertisements for plastic surgery sprawl throughout Seoul’s affluent Gangnam neighborhood. There is seemingly an Olive Young on every street corner and endless high-end options in shining department stores. The industry works hard to conceal the dark historical context behind Korea’s coerced preoccupation with female beauty, while continuing to push what sociologist Rosalind Gill calls the “surveillant gaze”: symbolic images of measuring tapes, cameras, and microscopes that incite women to constantly monitor and regulate themselves. K-pop labels routinely debut girls as young as fourteen to appeal to teens, both locally and internationally. Appearance-based discrimination is endemic; journalist Elise Hu writes in Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital that for Korean women in the 21st century, looking pretty is “the price of entry in the labor market.”

Lily:

I’m a size small in America, a medium in Taiwan, and a large in South Korea.

For a country with such a famous beauty industry, the selection of lip colors and finishes is extremely limited. Nearly every Korean lip product is sheer, glossy, and pink, formulated to stain your lips for a longer-lasting effect. Eyeshadow palettes lack pigment and are similarly uninspired. While American makeup brands market their products as tools of self-expression, cosmetic advertisements in Korea use words like “perfection” 완벽 and “improvement” 개선 to draw consumers’ attention.

Korean sunscreen, however, is excellent, as are the face masks and jelly foundation cushions (provided you can find one in your shade). The products are very affordable compared to American cosmetics. I browsed many Olive Young stores that were packed with shoppers, yet the single aisle dedicated to American and European brands was always totally desolate.

Similarly, people seem to prefer beige or pink nail polish. I got a set of dark red gel nails done during my trip, and while the service was very fast with lots of attention paid to cuticle care, the final product was unfortunately lacking due to the technician’s lack of experience shaping stiletto (pointed) nails.

People don’t wear much color here either, and instead opt overwhelmingly for beige, white, black, brown, or muted shades of blue.

On Korean Food

Korea excels at making coffee taste good, and Korean people love coffee so much that we saw people sitting in cafes drinking coffee at 9 o’clock at night. In a similar vein, this country doesn’t rise particularly early — most businesses (including many coffee shops/cafes) don’t open until 10 or 11 am. Survey data indicates that South Koreans are highly sleep-deprived compared to other developed nations.

October is the peak month for gejang, raw crab seasoned with soy sauce. I was skeptical at first, but the crab we ate was incredibly fresh with a delicate and complex flavor.

One of my favorite dishes was North Korean-style cold noodles 물냉면, which are made of buckwheat and would fall apart if served hot. They come with julienned apples and a boiled egg, and are served in a refreshing broth with a bit of vinegar.

America supplied the ROK with food aid during the Korean War, and as a result, South Korea developed a serious taste for corn. Convenience stores carry cream-filled cornbread, corn-flavored ice cream, corn-flake-filled granola bars, corn chips, and rice balls full of corn and tuna. Teas made from roasted corn and corn silk are also popular beverages. Only 1% of this corn is actually grown in Korea — the vast majority is imported from the US.

Korea also consumes a truly staggering amount of fake sugar — ice cream proudly labeled “low sugar” is packed with stevia. The yogurt drinks and matcha lattes I ordered in cafes were sweetened with stevia by default, as were bottled teas and protein shakes in convenience stores.

Korean convenience stores have wonderful smoothie machines. For 3,000 KRW (US$2.10), you can pick out a cup of frozen fruit and have it blended in front of you. Be sure to purchase your fruit cup before you blend it to avoid violating smoothie procedure.

Chinese people have a joke that when you vacation in Korea, you get constipated due to the lack of green leafy vegetables. This joke ignores Kimchi and salads, of course — but it’s rare to find blanched greens of the sort that are ubiquitous in China and Taiwan.

Irene’s travelogue in Gwangju

I read Anton Hur 허정범’s 2022 short story “Escape from America” on the bus from Seoul to Gwangju. The great translator of contemporary Korean fiction writes his own dystopian tale: in a not-so-distant future, politics force him and his husband to flee America for South Korea, where democracy persists but their marriage is not recognized — a “reverse-Miss Saigon scenario,” the narrator notes sardonically. Fears of martial law, borders, gender wars — it all felt eerily prescient in the first months of new presidential administrations in both Korea and the US.

Korea’s Gwangju Uprising is often forgotten as an early chapter in the waves of pro-democracy movements that shaped postwar Asia. In part, that’s because the news simply didn’t get out. Only one Western reporter — Jürgen Hinzpeter for West Germany’s public broadcaster, whose experience was dramatized in 2017 by the film A Taxi Driver — was on site when troops began violently containing protesters on May 18th, 1980. Korean media was heavily censored at the time, and many outside South Jeolla Province, of which Gwangju was then the capital, did not learn of the killings until much later. The military dictatorship installed an effective blockade of the city for ten days, cutting off roads and phone lines, while local students and workers built a short-lived self-governance commune and organized themselves into citizens’ battalions.

Chun Doo-hwan 전두환, then-lieutenant general of the military and the main orchestrator of the massacre, officially became president three months later in 1980 and remained in power until 1988. For years after the massacre, Gwangju was a forbidden topic. The novelist Han Kang 한강, who became Gwangju’s most famous daughter with her Nobel Literature win in 2024, was in Seoul in 1980 and only found out about the atrocities from her father’s secret album of Hintzpeter’s photographs years later. The official death toll stands at 164 civilians, but many more disappeared or were not identified in time; the actual number of deaths may be in the thousands. An “unknown martyr” grave in the Gwangju May 18 National Cemetery contains the body of a 4-year-old child shot in the neck.

“That afternoon there was a rush of positive identifications, and there ended up being several different shrouding ceremonies going on at the same time, at various places along the corridor. The national anthem rang out like a circular refrain, one verse clashing with another against the constant background of weeping, and you listened with bated breath to the subtle dissonance this created. As though this, finally, might help you understand what the nation really was.”

— Human Acts, Han Kang (trans. Deborah Smith)

The “gwang”/광 in Gwangju corresponds to the Chinese character 光, which means light; Gwangju, then, is the Land of Light. I’ve never been to a city with as many commemorative statues as Gwangju. There is an entire park dedicated to statues in the western part of the main city, the government having commissioned artists to explore and immortalize the city’s history. A walk through the park crescendos with a large metal depiction of three students, their arms reaching forward and their faces bearing solemn expressions in a surprisingly socialist-realist style. Under their bodies is an entrance to an underground chamber, in which the names of all known victims surround another statue, this one of a mother holding the body of an agonizingly young teen — a modern Korean Pietà.

Gwangju is not just expressive about its past; it is passionately, thoroughly meticulous. The Jeonil Building, one of the city’s most iconic structures, has been renamed Jeonil 245 after the 245 bullet traces found on its top floors. The directions and depths of each trace conclusively prove that paratroopers shot at people from helicopters, a fact often disputed by those seeking to minimize the extent of cruelty inflicted on Gwangju’s people. Jeonil 245 contains an entire exhibition dedicated to repudiating false claims about Gwangju, including the oft-repeated far-right conspiracy that North Korea instigated the uprising. The nearby 518 Archives is a ten-floor building that houses documents about the events of May 1980. The top floor allows visitors to watch traffic underneath from the exact same windows where Catholic clergymen watched the military brutalize young students marching from Chonnam University. Some of those clergymen would later stage hunger strikes for democracy and clemency for protestors throughout the 1980s. The Old South Jeolla Provincial Hall, where resistance forces staged their last desperate fight, is currently being restored. Every single exhibit I went to was free to enter and had decent-to-excellent English signage.

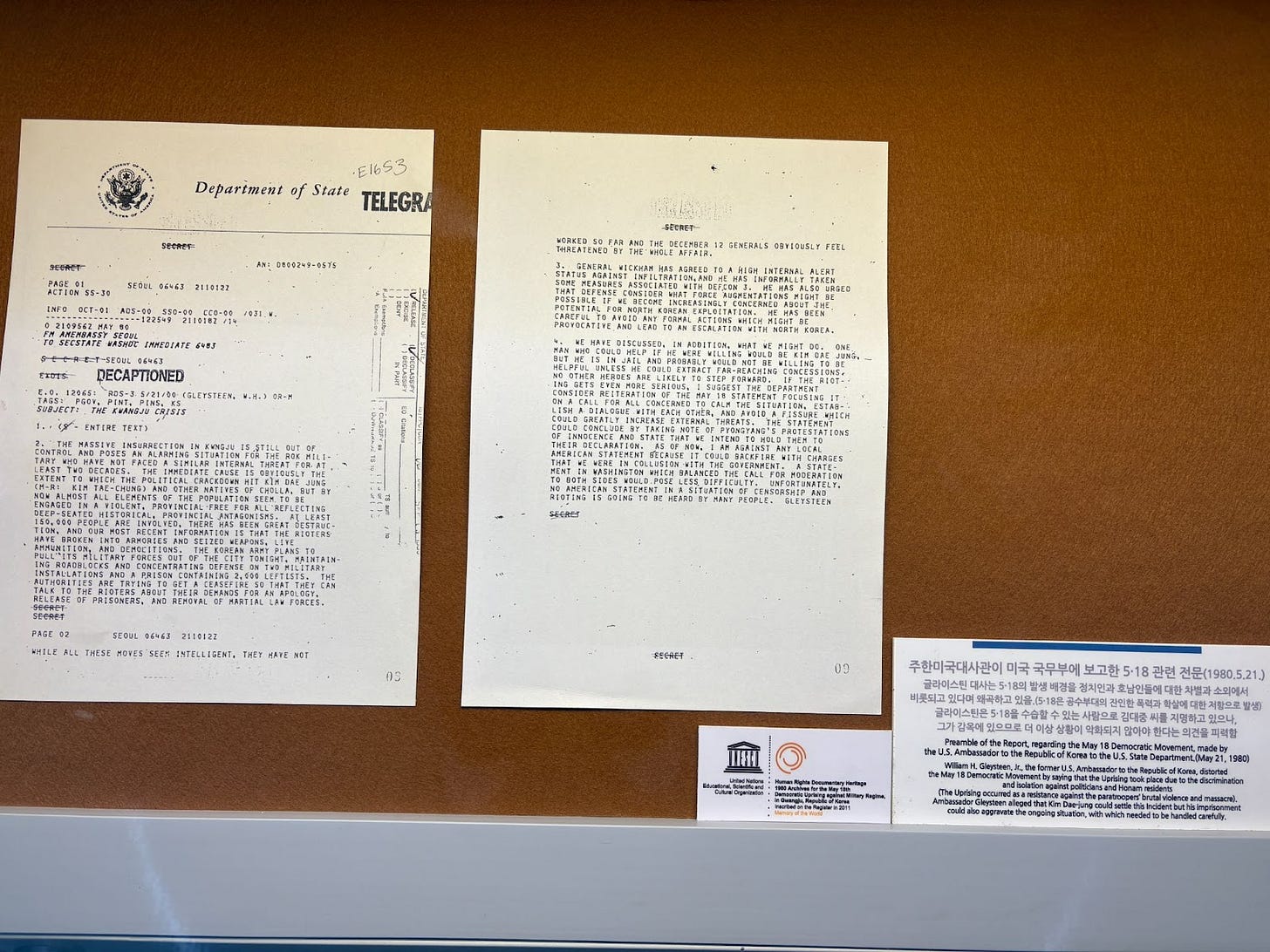

This is because Gwangju knows its memory can be inconvenient. In the South Korean narrative, Gwangju’s dead are now martyrs who gave their lives for today’s democracy, but that extraordinary achievement does not feel complete. President Yoon Suk-yeol 윤석열, who demanded the death penalty for Chun Doo-hwan while a law student in the 1980s, briefly imposed martial law of his own in December 2024. Korean politics today, haunted by the North-South division, still struggles to move past Red Scare paranoia. On the American side, Washington’s complicity in the Gwangju Massacre is a delicate topic for the US-ROK alliance. President Jimmy Carter’s administration, judging maintenance of the security status quo in the Peninsula to be more important than its people’s democratic aspirations, authorized the use of South Korean troops under the Combined Forces Command against protestors. Declassified documents show that US intelligence judged the protests to be “riots” caused in part by “deep-seated historical, provincial antagonisms” in Jeolla, and feared exploitation by Pyongyang even without any evidence of North Korean instigation. Gwangju became one of the darkest, yet most obscure, chapters of the Carter years; the legacy he left in Asia was barely acknowledged when he passed away at the end of 2024. And finally, across the East China Sea, Gwangju strikes too obvious a parallel with China’s own event that must not be named. Han Kang’s Human Acts has never been translated into Simplified Chinese by any mainland publishing house, so Chinese readers have to resort to pirating the Taiwanese translation.

Efforts by public history institutions and civil society have allowed the year 1980 to persist in Korean popular memory, even before Han Kang’s recent Nobel win. UNESCO officially listed documents of the Gwangju Uprising on the Memory of the World Register in 2011, prompting a wave of public commemoration. In 2013, the K-pop boy band SPEED released a two-part music video set in Gwangju for their song “That’s my fault” 슬픈약속, to popular acclaim. Note how, at the 11:30 timestamp mark, the second video directly quotes the last broadcast made by Gwangju’s citizen militia at the end of the Uprising:

Protest songs from the Gwangju era have also outlived the Uprising. March for Our Beloved (임을 위한 행진곡), the most well-known one, is now a social movement ritual across Asia, having been adapted by activists in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand, and mainland China for a variety of causes. Citizens in Seoul once again sung it while protesting Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration in December 2024:

Gwangju today is known as Korea’s progressive hotspot, and there is indeed a Portlandia-esque energy coursing through the city. Hipster cafes, lush green parks, and private museums weave around statues of death and survival across the city’s main arteries. The central square, where protestors gathered again to call for the ousting of Park Geun-hye 박근혜 during the 2017 Candlelight Revolution, doubles as a futuristic plaza for the Asian Culture Center (ACC), which showcases experimental art from across the continent. I visited on a rain-drenched day, and there were still large crowds at the ACC enjoying a pan-Asian food festival and open-air dance film screening. The ACC’s ten-year anniversary exhibition, Manifesto of Spring, sports a headline piece with a brassy premise: in a not-too-distant future, democracy collapses in the West and a political refugee tries to immigrate to “Seoul Land” by participating in a population growth program.

The Land of Light, like the rest of us, is surrounded by the haunted fires of history. It insists on sifting through the ashes.

“Why are we walking in the dark, let’s go over there, where the flowers are blooming.”

Tourism in Seoul

Lily:

Seoul is an underrated tourist destination. The city is full of beautiful green spaces connected by excellent public transit, and the early October weather was perfect for long strolls through the sloping streets.

The Korean writing system is a joy to learn, and just a little bit of study can really enrich your experience in Korea. It’s phonetic, and the letters elegantly fit together to form syllable blocks. The shape of the letters is also roughly based on the shape of your mouth when pronouncing each sound (for example, “ㄱ” makes a hard “g” sound, “ㄴ” makes the “n” sound, and “ㅈ” makes the “ch” sound). Irene and I had a great time sounding out menu items, buttons on appliances, and public transport signs, discovering tons of cognates with Chinese in the process. If you add a Korean keyboard to your phone, you can use the letter “ㅗ” to give someone the middle finger over text, and represent crying faces with “ㅠㅠ” and “ㅜㅜ”.

i had no idea about the gwangju uprising. Thank you for sharing.

omg so right about the shock of the lack of leafy vegetables! (except for the bbq wrapper leaves ofc). and thanks for the nod to Flawless!