Betting on Chaos: Professional Political Gamblers

101 on Polymarket and Kalshi

What does it take to make a living betting on politics? Can prediction markets offer insights about the future that other analyses cannot?

To find out, ChinaTalk interviewed Domer, a professional prediction markets bettor. Domer is the number one trader by volume on Polymarket, and he’s been trading since 2007. He initially entered this world through poker, but now makes bets about who will win foreign elections, whether wars will start, and which bills will become law.

We discuss…

Why some issues — like Romanian elections, the NYC mayoral race, or Zelenskyy’s outfit choices — can attract hundreds of millions of dollars in trading volume,

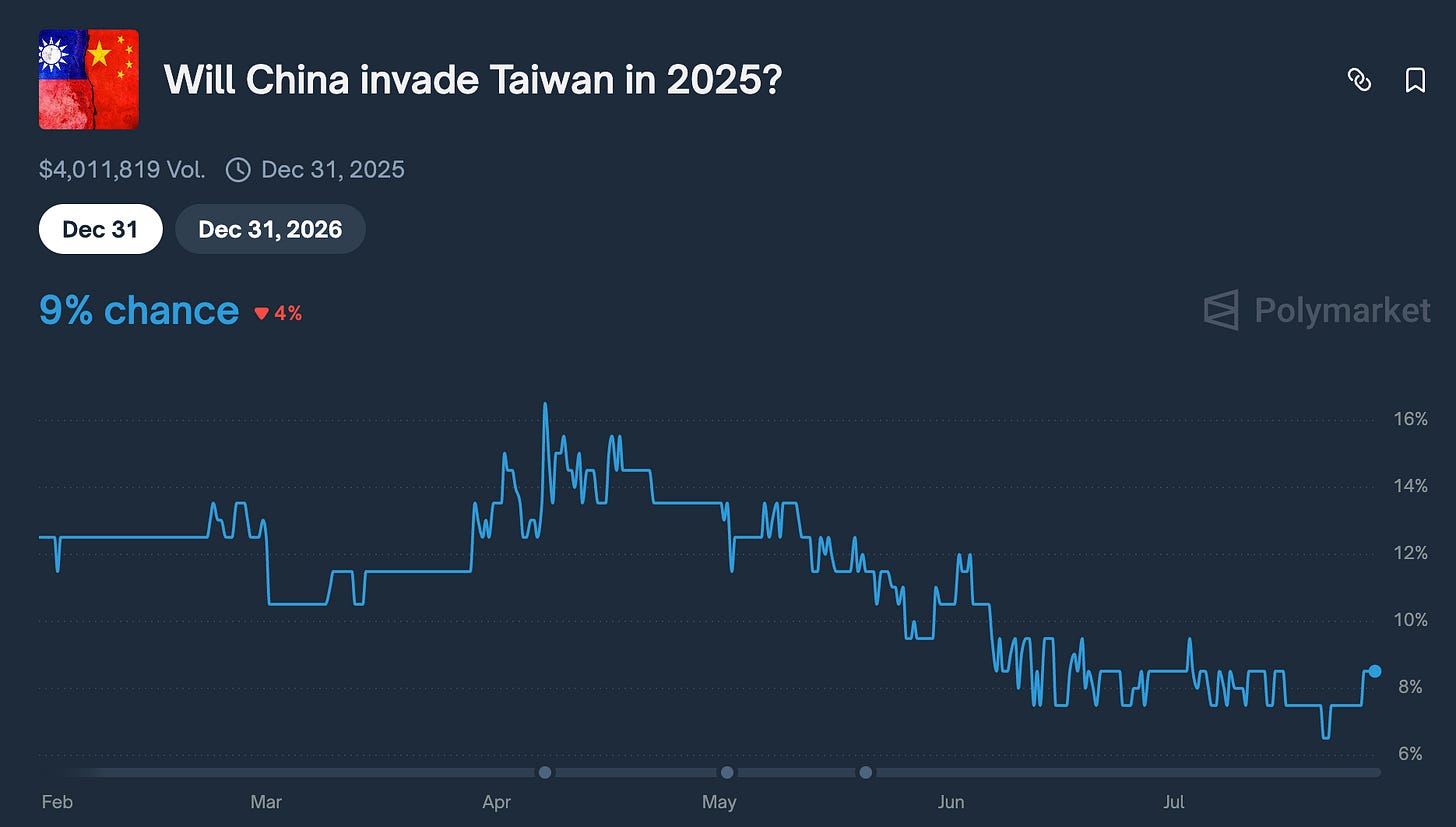

Systematic biases in prediction markets, including why they overestimate the likelihood of a Taiwan contingency,

What happens to prediction markets in the absence of insider trading regulations,

Why prediction markets are still a solo endeavor, and what a profit-maximizing team of traders would look like,

Bonus: How betting markets backfired on Romanian nationalists, what AI can teach you about betting, and other insights on winning from one of Domer’s contemporaries.

Listen now on iTunes, Spotify or your favorite podcast app.

This episode is brought to you by ElevenLabs. I’ve been on the hunt for years for the perfect reader app that puts AI audio at the center of its design. Over the past few months, the ElevenReader app has earned a spot on my iPhone's home screen and now gets about 30 minutes of use every day. I plow through articles using Eleven Reader’s beautiful voices and love having Richard Feynman read me AI news stories — as well as, you know, Matilda every once in a while, too.

I’m also a power user of its bookmark feature, which the ElevenReader team added after I requested it on Twitter. ChinaTalk’s newsletter content even comes preloaded in the feed.

Check out the ElevenReader app if you’re looking for the best mobile reader on the market. Oh, and by the way — if you ever need to transcribe anything, ElevenLabs’ Scribe model has transformed our workflow for getting transcripts out to you on the newsletter. It’s crossed the threshold from “95% good” to “99.5% amazing,” saving our production team hours every week. Check it out the next time you need something transcribed.

The Rise of For-Profit Forecasting

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with the basics. How do these markets work, and how are they different from buying Apple stock or betting on a sports game?

Domer: It’s somewhat similar to betting on a sports game. The most popular market by far is predicting who will win the US presidential election. This happens every four years, and it’s not just Americans who are interested — people around the world like to participate.

The system works on a 0 to 100 scale that assigns odds. For instance, in the 2016 Hillary versus Trump race, Trump had about 30% odds to win going into election day. If you wanted to bet on Trump, you might bet $3. If he loses, your bet goes to zero. If he wins, it goes up to 100, so you’d get $10 back.

It’s basically a binary outcome — you either win zero or you win 100, depending on whether your prediction comes to fruition.

Jordan Schneider: For context, we now have eight figures being bet on the outcome of the New York City mayoral election. We have $200 million of volume traded on whether Zelenskyy will wear a suit before July. These markets are extremely liquid, with millions or tens of millions of dollars in volume. We reached billions during the presidential election, but even niche topics like a Romanian mayoral election saw $6 million in total volume traded.

This is no longer a niche phenomenon. Dismissing these numbers as lacking proper price discovery compared to the trading volume of NVIDIA or Apple isn’t necessarily accurate. How have you seen the relative efficiency of these markets change as they’ve grown larger and more popular?

Domer: They’ve grown tremendously since I started. When I first began, a $10,000 bet made you a big whale. Now you’re just a small fish in the ocean. As they’ve gotten bigger, they’ve also expanded significantly in scope.

When I started, there were basically two major markets: who would win the presidential election, and who would win Best Picture at the Oscars. Now it’s become this widespread phenomenon that encompasses many countries, numerous races, economic predictions — like what the Fed will do. The breadth of topics and the level of participant interest have exploded.

Jordan Schneider: I’m curious about the professional approach to this. How would you describe your process? Let’s pick something more esoteric than a presidential election — maybe you could walk through the Pope example or another market you’ve been analyzing. What does it take to develop an edge in these topics?

Domer: At the basic level, succeeding in these markets requires two things. First, you need to be a curious person who’s eager to learn. Second, you need to enjoy following the news and staying current with daily developments in various stories.

Take the Pope example. Papal conclaves only happen every 10 to 15 years. These aren’t areas where people maintain expertise — you have to dig into archives to understand what happened last time and read stories from 15 years ago about how these events unfold. You need to train yourself to examine all the contours of an event.

When a pope passes away and they’re selecting a new one, everyone interested in betting starts at the same point. You’re competing against perhaps a thousand other people, all beginning from the same starting line. Success comes down to whether you can research faster, better, and more accurately than your competitors. That’s essentially what my job entails.

Jordan Schneider: What’s interesting, as you’ve mentioned in past podcasts, is that even with niche topics like a Romanian election or Israeli politics, the betting pool isn’t dominated by Romanians or Israelis reading local news sources. Even when there are locals involved, the center of gravity consists of international observers. The local knowledge advantage isn’t as pronounced as you might expect.

Domer: That’s mostly accurate. The center of any election market will be people who aren’t necessarily subject matter experts. However, it will attract a minority of people who live in the region or are directly impacted by the event. This brings in additional interest and new participants, though that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re more informed.

Being closer to an event might actually create bias. If you have a personal interest, you might bet on someone you’re rooting for, whereas as an American, I’ve never heard of this candidate, so I don’t have a rooting interest. Various factors come into play regarding whether someone directly impacted by an event will participate and how that affects their judgment.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss the social utility argument for these markets. Having accurate betting lines on the Knicks and whether they’ll win on any given Tuesday night — providing a price discovery function for that — doesn’t seem particularly beneficial for the world. But it’s very different when you’re talking about whether wars will start or end, elections, and similar events. As prediction markets have grown in prominence and sophistication, how has your thinking evolved about their broader utility?

Domer: That’s an excellent question. Consider a world where prediction markets don’t exist at all. If you’re trying to figure out whether there’s going to be a recession this year, you’ll typically rely on pundits to inform that decision. The world of punditry doesn’t reward you for being right, nor does it punish you for being wrong. It revolves around entertainment — is this pundit convincing? Is he entertaining? Is he saying interesting things? That’s the nature of punditry. It’s not necessarily punishing you for being wrong or rewarding you for being right.

Prediction markets are essentially the next level of punditry. They’re not a perfect solution — if Polymarket says the chance of a recession is 25%, that doesn’t mean we have the definitive answer. Nobody came down from heaven and declared it’s 25%. We have no idea. But it’s a more advanced form of punditry where you are punished if you’re wrong and rewarded if you’re right. It’s punditry with skin in the game.

Obviously, prediction markets encompass more important topics than sports games, though that’s not to say betting on sports isn’t fun or important for people who are interested in it. It’s just a different facet of predicting outcomes.

Jordan Schneider: As you start to see news stories about prediction markets and politicians feeding off those stories — particularly with Vivek Ramaswamy over the past few months, as his number crept up from 1% to 5% to 10% — this became a tangible way for him to demonstrate his momentum. Are you seeing more of these feedback loops where prediction markets manifest in reality, which then manifest back in prediction markets?

Domer: It’s a fascinating question because it raises the possibility of the tail wagging the dog. If this happens, it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy where someone with deep pockets goes onto one of these markets and bets themselves up. Then they can say, “I have momentum. Here’s proof. Someone’s betting on me. My price is going up."

There’s a perfect example from 2012 during the GOP nomination, which was essentially a clown car with multiple candidates going up and down — Herman Cain, Mitt Romney (who ultimately got the nomination), Rick Perry, and others. Every week brought a new frontrunner — Newt Gingrich, and so on. Interestingly, during the summer, someone on InTrade

was buying massive amounts of Donald Trump contracts — ridiculous amounts, way above where the market should have been. I was thinking to myself, “This might literally be Donald Trump or one of his associates.” Back then, the market wasn’t as liquid, so maybe the person was spending $50,000 on this, which is significant but essentially functions as a commercial. Was this guy preparing to run and trying to boost himself? I thought it was an interesting case study.

Going back to your question about whether the tail wags the dog — yes, I think there are interesting feedback loops. The other factor is market liquidity. Sometimes these markets have more liquidity than the event’s apparent importance would suggest, like the Zelensky wearing a suit market.

Jordan Schneider: What’s interesting is the story from the 2024 election about the “French whale” who was buying up Trump contracts, basically driving the price up five or six points for only $25 million. In the context of a presidential election, that’s equivalent to a handful of ads, which might win you a few votes. Instead, it created an entire news cycle about someone knowing something others don’t, and voters tend to vote for winners.

This dynamic seems very affordable, especially in something like a New York City Democratic primary, where it would cost only $50,000 to $100,000 to get Brad Lander’s name on the map as having momentum. I’m surprised it isn’t happening more frequently. I guess we’ll reach that world eventually. Maybe these markets just need to be liquid enough for someone to make enough money on the other side to buy it back down.

Domer: You mentioned the French whale — I was actually one of the people who helped break that story. One really interesting aspect was that people would DM me their guesses about who it was. The number one guess by far when the story first broke was that it was probably Elon Musk, because he had started a super PAC and has enormous wealth. To him, this would be a drop in the bucket. It made total sense that one of the benefactors would be the one doing this, rather than some true believer who had been investigating and conducting polling.

Jordan Schneider: What’s interesting is that the narrative reinforcement cycle seems most relevant for elections. But there are markets where it’s basically one person making a decision — will Trump bomb Iran? Will Netanyahu bomb Iran? Will Hamas and Israel make a peace deal? Will Zelensky wear a suit? The momentum behind these predictions is unlikely to influence outcomes, or maybe it does. Perhaps we’ll reach a point where these numbers become so prominent that a president will feel they’re letting people down if they don’t do what the markets expect, which could become self-reinforcing and factor into their calculations.

Domer: That’s a fascinating and relevant question, and I’m not sure I have a good answer. It’s something I grapple with — whether the markets could theoretically get too big for the actual events they’re trying to predict.

Jordan Schneider: The other issue is there’s no SEC oversight — no insider trading regulations. There are plenty of people who know whether many of these things will happen. No one knows who’s going to win a presidential election, but there are many markets involving specific decisions where insiders exist. If I’m some random person in Iran working in the IRGC and this is my one opportunity to make $10 million because I know whether we’re going to attack America back, why not? How do you think about the insider trading dynamic, and has it manifested at all?

Domer: What’s interesting is that I’ve been doing this for such a long time, and from the beginning, people’s first reaction to big swings is, “Oh, some insider is betting on this market.” 99.9% of the time it has nothing to do with an insider. It’s a true believer or somebody who clicked the button by accident or similar.

But lately, with the markets getting so big, I’m becoming more suspicious. There were a few markets recently asking what Israel would do, and these accounts that were newly created and funded with $100,000 or so came in. They only bet on this one market — Israel’s going to do XYZ. It happens, and then they withdraw. This behavior seems exactly like what an insider would do. As the markets become bigger, my initial assumption that 99.9% of the time it’s never an insider starts to break down given how much money is involved.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting because specifically on international relations, there are DOJ indictments showing how much money people make when they’re caught spying. If you’re a really good spy selling secrets, you probably make a few million dollars. Once these markets are big enough where you can make $10 million in an afternoon through crypto with no one knowing, or you can convince yourself you won’t get caught, this creates a new dynamic.

Not many national security establishments or intelligence agencies have processed this yet: why sell my secrets to the Chinese when I can tell the world 24 hours or even three hours before something happens by making a bet on it, then retiring six months later and moving to Bermuda?

Domer: You’re exactly right. It’s untraceable. But I do think the arc of these markets is toward regulation. This might not be a 20-year problem, but it could be a problem over the next few years as we figure out regulations.

Jordan Schneider: What would that look like? Would you have to trade with a driver’s license? That would probably solve some of those issues, right?

Domer: It could. This is a fraud issue not only with crypto, but trading in general regarding the depth to which you examine your customers and their funds. If you’re going to put up markets sensitive to national security and trade in a country where those national security issues are very important, then the arc of these markets seems to be toward disclosure rather than obfuscating what’s actually happening.

Jordan Schneider: What’s your take on the broader ethics and where you would draw the line? We already have markets that are pretty close to death markets — asking when a leader will lose power. It’s not phrased literally that way for smart legal purposes, but where would you draw the line on what’s not acceptable to trade on?

Domer: It’s a hard question. If you think about a straight war market — will Russia and Ukraine get into a war — and you rewind four years, this was a really important question. People should know the answer to this. We should be trying to figure out what the answer is, and prediction markets are really good at figuring this stuff out.

I see both sides of the argument because it does feel distasteful. Obviously, it’s not just economic impacts or world impacts, but people on an individual level are going to be hugely impacted, possibly in negative ways. In that aspect, it feels unseemly. But to me, the importance of the event overtakes the unseemliness because we’re answering questions that need to be answered. We need to assign a probability to some of this stuff to an extent.

Jordan Schneider: One class of questions that makes me really uncomfortable — and it doesn’t really exist on Polymarket yet, but occasionally shows up on Manifold — are these very personal ones about people who aren’t celebrities. If you’re in high school and you can make a betting market on whether this couple will break up, that seems problematic. It’s similar to how no one’s allowed to bet on high school sports, and you can’t do prop bets on college athletes. You don’t need to expose anonymous individuals to this stuff.

Then you have this sci-fi arc where a lot of those Biden markets were kind of like Biden death markets. The assassination connection to some of these feels unseemly, but having some sense of the probability that Putin will succeed in assassinating Zelensky is useful. But then you have horrible incentives where someone bets on it and commits an assassination. There are enough crazy people out there, right?

Domer: It’s definitely something we need to grapple with. I’m not sure I have the answer. I do agree that not everything necessarily deserves a market, and where we draw the line between what gets a market and what doesn’t requires careful consideration.

Jordan Schneider: As you trade and see these markets move, I’m curious about the balance between slow versus fast thinking. On one hand, you mentioned the Pope earlier — how you want to understand how past conclaves played out and get the backgrounds of all the different players. But once news starts happening, these markets can move very quickly. It seems there’s a lot of money made and lost in responding to breaking news and processing it correctly. How do you think about that conceptual difference, and how has the speed of these markets changed over time?

Domer: It used to be that if you read some tweet and logged into the market, it might take minutes for that tweet to be fully incorporated. By tweet, I mean some breaking news event, which is usually encapsulated in a quick tweet. But if you look at what’s happening recently — in the past few months — if you take more than three seconds to react, you’re glacially slow. The speed of these markets adapting to news has become so much faster than it used to be.

You have to be very careful and quick in how you react to things. But then the second-order effect is that once the quick reaction has happened, you need to think slower about it. You need to figure out whether this actually makes sense, because sometimes the initial move isn’t necessarily correct.

A Rōnin’s Game

Jordan Schneider: Is there algorithmic trading like there is on public financial markets, or is it just more people who click faster?

Domer: Someone at a VC firm was actually asking me about this the other day because they’re looking into it. I know at least two people have tried it, and there wasn’t much success. I know in one instance — because I invested in this guy, and he now works for an AI company — it didn’t work out for us, but it worked out for him.

It hasn’t been successful yet that I know of. Who knows? Maybe there are people with secret Polymarket accounts using AI agents, but it’s coming.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting because we’re now very much in a world where AI processes quarterly reports and listens to earnings conference calls in real time. It does it faster and probably better than the analyst sitting there. But the fact that this hasn’t come to Polymarket yet is partially a function of there being less money to be made. Maybe there’s also something about these markets being much more idiosyncratic than comparing this quarter’s Walmart returns to last quarter’s.

Domer: There’s a very strong qualitative element to it, not necessarily quantitative. Not that AI is amazing at quantitative analysis yet either, but there are idiosyncrasies, intricacies, and little things in the rules that may alter a market one way or another. AI isn’t quite at that level yet.

Jordan Schneider: Are there teams trading yet? Is it still mostly an individual game?

Domer: At the high level, yes, it’s individual. I know teams have been created around the presidential election because there’s a lot of information out there and you need to get it very quickly. Teams were created for the US presidential election. I was on a team for that in the previous two elections.

But most of the time, I describe it as being rōnin — we’re individual samurai going about our lives. We talk to a lot of the other rōnin, but we are not necessarily coordinating with them.

Jordan Schneider: This is the financial parallel of hedge funds, right? Now you have entire — almost all of the most successful hedge funds have dozens, if not hundreds, if not even a thousand-person research teams. Can you talk me through an example of a market you traded where you felt like if you could duplicate yourself and had more research, you could get more of an edge? Is it wider coverage where you think there’s more alpha? What could a 10-person outfit potentially do in this space?

Domer: People have approached me about forming a team, so I know a little about it. Where you would really want to focus is making sure everybody has different strengths. If I were building a 10-person team, I would want somebody really strong on politics, somebody really strong on foreign politics, somebody really strong on quantitative things and statistical modeling. Then I would probably want to duplicate each of those people so there are two people doing the same things.

The other thing about prediction markets that doesn’t get much focus compared to financial markets is that prediction markets are 24/7. The news doesn’t sleep. If you’re trading financial markets, you can safely get your eight hours of sleep. You could theoretically do that and not miss any news whatsoever, but in prediction markets, sleep is the enemy. It’s very dangerous to sleep. If you’re building a team, you would probably want redundancies and widespread expertise in many different areas.

Jordan Schneider: You said you talk to a lot of other people in this space. Give us a little anthropology — who are these folks who make up the majority of trading in the market?

Domer: I come from a poker background, and a poker player is probably a good benchmark to think about these players. It’s mostly young men who like taking risk, who are good at math, good at analyzing things, and interested in the world. That describes 95% of people using prediction markets.

Jordan Schneider: That’s interesting because poker is about getting better at this very closed system, right? There’s an aspect of reading human beings, but every new market you explore, you’re learning something novel — about a new country or situation or politician or something about the economy. There’s a different type of curiosity between someone who wants to memorize all the openings in chess or all the hands and ratios in poker versus someone willing to play in such an open-ended space as political prediction markets.

Domer: A poker player or chess player is very math-focused and very good at pattern recognition, which includes reading the opponent and reading patterns. That’s an element of prediction markets. But to your point, the other element is creative thinking and being able to pivot from one topic to another that may be very disparate and may not be related at all, but you can notice similarities and quickly come up to speed on a new topic. It’s not only the chess or poker element, but also creative thinking.

Jordan Schneider: Another thing is that there’s not a lot of emotional valence and connection that you have with any given poker hand, aside from your personal investment in it, as opposed to a war starting or a presidential election. I’m curious how you and other folks have trained — or maybe anesthetized is not the nicest word — but how you divorce yourself from the actual developments in order to be a more clinical analyst of this stuff.

Domer: I was nodding nonstop to that question because it absolutely applies. You have to divorce yourself because I’m a person who reads the news. I watch a lot of news. I follow the news. I’m well aware of the world. I talk with other people. I talk with my spouse, and I have very strong opinions. You have to leave those opinions at the door, which is very hard to do.

If you’re trying to predict something that you want to happen, maybe limit yourself to only a couple hundred bucks and not really try to make a living betting on things that you want to happen or betting against things that you don’t want to happen. You have to both put it at the door and self-limit yourself — not get too involved in something that you want or don’t want to happen.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of a topic people have strong feelings about, a lot of politics in these markets involves modeling the thought process of Donald Trump. What are the mental models of his decision-making that you’ve found most helpful over the years?

Domer: The big-level view of Trump is that he’s very chaotic, and chaos is great for prediction markets. If you just have a president like Biden, Biden didn’t fire a single cabinet secretary. The only cabinet secretary that left was going to become the commissioner of the NHL. If you have this very boring presidency versus this very chaotic presidency, obviously the chaotic presidency is going to be much more conducive to predicting what’s going to happen next and people following what’s going to happen next.

But the interesting thing about Trump is he’s changed between his first presidency and his second presidency. In his first presidency, he was firing people all the time. He probably had three cabinet secretaries fired within six months. Left and right, there was controversy after controversy. This time, he’s weathering through it.

The interesting model of this presidency is he’s moved to an Elon Musk type of over-promise, under-deliver, especially on trade deals. He’s constantly threatening to “whack this country,” but when it comes down to it, he pulls back. It’s interesting not only trying to get into the mind of Trump, but also how Trump has changed from one presidency to the next. He’s gotten less chaotic in some ways, but more chaotic in others, particularly in how he’s dealing with economic policy. It’s very hard for a company to plan if they think there’s going to be tariffs one day and no tariffs the next day. It’s a very different type of chaos in this second Trump presidency.

Jordan Schneider: How have you applied the reality television framework in the past?

Domer: Somebody smarter than me said a long time ago that if you want to figure out who Trump is going to pick for something, print out pictures of everyone he’s considering. Go up to a random person and ask, “Who would you cast for a TV show if you were casting a Supreme Court justice?” The person they point to is probably who he’s going to pick because he’s casting his show.

That’s how I think about Trump — a lot of what he’s doing is focused on presentation. He’s the star of a TV show and that’s how he treats much of what he’s doing, not only personnel decisions (are they good on TV?), but also policy. Does this sound strong? Do I look strong? A lot of what he’s doing is entertainment-focused, and that’s obviously his background as well. He’s been a showman since the 80s when he took over from his father. I think that’s a very strong core tenet of Trump — the entertainer, somebody who’s trying to keep people engaged with what he’s doing, a marketer.

Jordan Schneider: What are your heuristics for separating fact from fiction — dealing with fake news?

Domer: What do you mean by that?

Jordan Schneider: What you have to do as someone who works in prediction markets is essentially high-stakes news literacy with money on the line. You have this mental model of what you think is happening, and then there are new data points that you have to process and react to. At the same time, you’re watching these markets move as other people react and process them. Are there news literacy heuristics that you think are broadly useful as a citizen? Or maybe category errors that you’ve seen these markets make over time, where they overread or underread into specific types of new data points?

Domer: That’s a really interesting question. There are two facets that come to mind. Number one is fake news. One of the markets recently is whether Elon Musk will form his own party. He’s made this big announcement with a lot of fanfare, but whether he actually does the paperwork is TBD — that’s what the market is about.

Recently there was this filing with the FEC pretending to be the American Party. It wasn’t actually true, but someone new to prediction markets might see this FEC filing, which looks very official. It’s on the FEC website. Somebody actually filled it out and put Elon Musk’s name on it. They’re going to see that and think, “Oh, the market’s over. He formed it. Yes. Easy money, free money.” But somebody who’s been doing this a long time knows that people make fake FEC filings all the time.

It comes from experience and being able to distill fact from fiction. If you’ve been doing it a long time, you’re definitely on the lookout for fake news because it happens all the time. Actually, it’s increased in frequency lately, especially with people trying to create fake news in order to profit from it, whether in financial markets or prediction markets.

The second part of your question that struck me was knowing which reporters to trust. This is very important, especially if you’re predicting American politics, because there are dozens of reporters covering Congress, the presidency, etc. A lot of the focus is on day-to-day drama: Is this bill going to pass? This person just said this, that’s happening. You have to be very careful about who you trust.

The longer you’re doing it, the more you learn. For instance, the Punchbowl guys — people in this space get tons of newsletters every single day. Punchbowl is one of the main ones, along with Politico. If you’re getting the Punchbowl newsletter and you see that the head of the Republican Party in Congress is saying this and that, and it looks like maybe the bill is in jeopardy — well, Punchbowl constantly slightly exaggerates whether a bill is in danger of passing or failing. They really play up the drama.

The longer you’re in this space, the more you realize the intricacies of reporters — who you can trust, who is reliable, who is constantly exaggerating what’s happening. It’s very important as a trader to be able to distill between what’s happening and what people are trying to pretend is happening.

Jordan Schneider: It is an ineffable thing that only really comes from following these stories in real time and seeing how people behave. It’s more nuanced and sophisticated than just giving any Punchbowl headline a 20% discount factor in your model.

As I’ve dabbled a little in the legal markets open to US citizens, it has been a remarkable and humbling learning experience. As someone who has been following news pretty closely and professionally since at least 2013, only trading in markets where I think I know something and being wrong a lot has taught me about probabilities and degrees of confidence. These markets are real now and liquid enough to have a lot of signal in them.

It’s a really useful exercise for people who work in and around politics to go from being a pundit to someone who’s forced to discipline their thinking and opinions about the future with a market. That didn’t really exist until relatively recently, whereas financial market participants were able to have that learning experience of taking views and seeing them play out correctly or incorrectly and gaining context and experience over time.

Don’t get addicted. Don’t spend a lot of money on this stuff. I don’t endorse gambling here on ChinaTalk, but as a learning tool to understand what the world is like, putting $10 in an account and trying to size markets and react to news is a worthy experiment to do for at least a month in a topic you’re interested in.

Domer: I would second that. It’s fun to do, even if you’re just doing five or ten bucks, because if you’re following it anyway, it gives you a little rooting interest, like watching a sports game. From that aspect, it’s really fun.

The other thing is that prediction markets are easy if you know what you’re doing, but it’s also very easy to lose a lot of money very quickly. For instance, if you rewind to last year during the Trump versus Biden debate, there were whole accounts that are just gone now because they didn’t think there was any chance that Biden would drop out even after the debate. I was thinking, “I don’t know, I’m not going to stake my account on this. It seems sketchy."

It’s not just about being able to predict things correctly, which isn’t that hard if you’re familiar with the space. The really hard thing is being able to avoid the pitfalls and not betting against things that are actually more likely than you think they are.

Jordan Schneider: Domer, there were three lines in one big beautiful bill that got a lot of professional gamblers very worried. Why don’t you give the audience some context?

Domer: In the House version, it didn’t exist. In the Senate version, nobody noticed it until after it passed. It was three little lines saying that for people who are betting professionally or even non-professionally, you can only deduct 90% of your losses.

What does that mean? If somebody is gambling recreationally and they win $10,000 and lose $10,000 — so they’re an even recreational gambler who didn’t win any money — if you can only deduct 90% of your losses, you can only deduct $9,000 from that $10,000. All of a sudden, even though you didn’t make any income, you now have $1,000 of taxable income.

You can imagine some professional gamblers — if you multiply that times 100, all of a sudden they have phantom income that is very large and they go from maybe owing $20,000 to owing $120,000, depending on the circumstances of the specific gambler. It can have a very deleterious effect on not only sports bettors but also poker players.

It’s TBD whether it impacts prediction market traders because there is some leeway where you can count it as a capital gain, mark it as a future, or whatever. It really depends on how the IRS classifies prediction market winnings in the future. But anything that’s bad for poker players or sports players, I view as akin to prediction market trading. It’s very, very not good.

Jordan Schneider: Maybe your markets are about to get a whole lot more liquid, Domer. If all the unproductive, socially unproductive sports gambling gets shifted into more efficient trading on markets that are actually useful for the world to have numbers on.

Domer: More competition is coming, which is not necessarily a great thing, but we’ll see how it goes. One thing that’s interesting about prediction markets is that often there are rule fights over things that you cannot possibly see coming, like this Zelensky suit where he wore a suit, but he didn’t wear a suit, and then it devolves into a rule fight and you’re arguing over the judges.

It’s easy to imagine that happening with Taiwan if China says, “Okay, this little outlying island that nobody lives on, we’re going to take it over.” But Taiwan says, “Well, that’s our island.” Did they invade or did they not invade? It’s easy to see how these markets that are important — we should have a market on whether China invades Taiwan — could get railroaded by very minute details.

Jordan Schneider: Currently, “Will China invade Taiwan?” has three and a half million dollars of volume and an 8% chance of happening in 2025, according to Polymarket. It’s defined as resolving to yes if China commences a military offensive intended to establish control over any portion of Taiwan by the end of the year. What are the things you’ve seen move that market in the past? What does 8% even mean?

Domer: You have to look at things not only from the event itself, but also the risk-free rate. Markets that don’t expire for a long time are going to trade in the mid-single digits no matter what. You can factor that into your analysis. What it’s basically telling you is it’s a very, very low chance of happening.

But the other interesting thing about that market is that it’s correlated with what’s happening with Russia and Ukraine. As Russia has more success, that market may start to push up — not necessarily this year, but if that market existed for 2030, maybe it’s trading at 25%. If Russia starts to have a lot more success, maybe it moves up to 30%, because these events are correlated and the US reaction to what’s happening in Russia-Ukraine also has a lot of impacts on that market as well. The interesting thing is how it correlates with other things happening in the world.

Jordan Schneider: The risk-free rate concept is important because when I see 8%, I think that’s insanely high. But you don’t earn the treasury rate for holding a position on Polymarket.

Domer: “Will aliens invade the US?” is probably trading at 4%. “Will Jesus return to Earth?” is trading at about 2.5%. There are markets where you can figure out what the risk-free rate on the site is. This is 0% chance of happening or a very, very small percent chance of happening. Everything pivots off of that. I would view the real odds [of a Taiwan invasion] as probably closer to 4 to 5%, which is still way too high in my opinion. But people disagree.

Jordan Schneider: You can earn about 3.9% by owning a treasury bill for a year. Getting to 2.5% for aliens or Jesus being resurrected — it’s like people will pay 2.5% to have a meme stock. Walk me through the logic of how we have these markets where you will not make any money and it sits for a long time.

Domer: I’m not sure what the logic is for the people who are buying yes, but bonding as a general concept is very popular in prediction markets where you’re betting on events that you think are impossible. For instance, aliens landing — that’s not impossible, but it’s so unlikely that it’s very close to zero. Plus, if you lose the bet anyway, I’m not sure you need to worry about money.

The risk-free rate on prediction markets usually sits in the mid-single digits for a year. It’s usually maybe 2 or 3% above the bond rate in the US.

Jordan Schneider: What would you say to policymakers or folks working on this stuff in Washington about how they should think about and interpret what they see on Polymarket?

Domer: First of all, I would focus on the liquidity. If it’s a liquid market with a lot of volume, then there’s been a lot of thought that went into this market and there’s a lot of money involved. It’s not just random people making bets and trying to move prices around for fun. People treat this very seriously. Number one, assuming that the volume is substantial and it’s pretty liquid, treat it seriously.

Number two, it’s advanced-level punditry. It’s not just people being paid to have opinions. It’s actually, “This is very important whether I get this right or wrong.” It’s the next level of people figuring out what’s going to happen in the future.

Number three, there can be some quirks on prediction markets that cause events to not necessarily be reflective of reality. For instance, “Will the US get an Air Force One jet from Qatar?” Looking at that from six months ago — actually taking possession of the jet may not happen for three years, but the big announcement may happen immediately. Sometimes there’s a little bit of lag between announcement and event happening, and that can cause prices to be a little askew from what you think they would be. It’s always important to pay attention to what the rules are in terms of what the event’s trying to predict.

Jordan Schneider: What’s been the most fun for you? Are there particular countries that you’ve really enjoyed getting to learn about, or questions that have — aside from the money-making aspect — what learning journeys have you gone on that you found most intrinsically rewarding?

Domer: I’m not sure I think about intrinsically rewarding versus monetarily rewarding. I have more fond memories of monetarily rewarding, I guess. But the countries I enjoy following the most are the most chaotic countries. If you look at Israeli politics or Italian politics or, a few years ago, South African politics — things are very chaotic.

It’s not like what’s happening in Canada, for instance, where they just rejected a populist and reelected the technocrat. They’ve had the same party in leadership for a very long time — it’s a very stable country. Whereas if you look at Israel, there’s elections every nine months maybe at this point, or in Italy where they’re switching parties from year to year.

The chaotic countries are far more fun because there are more events, they’re repeatable, and you know the ins and outs. People who joined the site a year ago don’t know about these six other Italian elections that you’ve predicted in the past seven years. I’m drawn to chaos in general — not necessarily in a negative way, but in a fun, dynamic way.

Jordan Schneider: It’s the oil trader energy when it comes to prediction markets. If everything’s too predictable, what’s the fun in that? It’s interesting how homework pays off. As an American who doesn’t speak Hebrew or Italian, what’s it like getting your handle on a foreign country’s politics? Or do you speak Italian?

Domer: No, I only speak English and un poquito de español. Number one, you’re subscribing to newspapers in foreign countries, which can be hard to sign up for because you’re not sure what to type in the sign-up fields. You’re also trying to get to a base of knowledge — you have to pretend that you’re a prediction market trader in Italy. Who are the top political people I need to follow? Who are the smart analysts? What accounts do I need to be following? You have to get up to speed.

The other facet is often I’ll be watching Israeli TV, and I have my phone out, literally holding my phone up to the TV and translating the chyrons in real time so I can understand what they’re saying. It can get ridiculous sometimes, but it’s fun. It’s funny. It’s a lot of work, but it’s rewarding.

Jordan Schneider: If you were going to teach a college class on learning how to make money in prediction markets, what would you put on the syllabus?

Domer: That’s a really good question. In my Twitter profile, I have a list of books. Going back to what I was saying earlier, it’s easy to teach people how to read politics and learn about politics. If you immerse yourself enough, you can get caught up. If you get the Politico newsletters, if you’re following people on Twitter, if you watch Meet the Press, if you’re watching the nightly news, you can get into it pretty quickly.

The harder part is knowing how to react quickly and not making big mistakes. From that perspective, I would probably teach very quick reacting — more the poker element and managing your bankroll. There are a lot of intricacies that would go into it beyond just the knowledge element. It’s how you think and how you react and how to not make mistakes.

Jordan Schneider: The mental ability to be calm when you have those big market swings, especially because AI can’t do it for you yet, apparently.

Domer: Yeah, I don’t know.

Jordan Schneider: We’ll throw some meditation classes in there, too.

Domer: The number one mistake I see people making, especially when they first join these markets, is being afraid to take a loss. Loss aversion is such a strong thing. It’s like, “Oh, I put 100 bucks in. I’m gonna try my hardest to get 100 bucks out.” They’re averse to taking that $20 loss and being at $80, whereas me, who’s been doing it a long time — if I think I’m wrong on something, oh my God, I’ll gladly take that $80 and maybe put it on the other side and try to get my money back that way. Being averse to taking losses is probably the number one mistake that people make.

Market Manipulation in Sen. Collins Votes and a Reckoning in Romania

For another perspective on prediction markets, we interviewed Jonathan Zubkoff, otherwise known as ZubbyBadger, who is also a full-time prediction markets trader.