Race for Space Law: Inside the Sino-American Cosmic Rivalry

Space exploration in the Cold War II era

As China prepares to select taikonauts for its first-ever manned moon landing, a new space race is quietly taking shape — not just over who will next set foot on lunar soil, but over who will shape the rules and norms governing humanity’s expansion into the cosmos.

What happens when 1960s space treaties meet 2020s tech? And how will Beijing and Washington compete to define space’s legal frontier? Pseudonymous contributor Ari fills us in.

Ari is pursuing a master’s in Chinese Studies with a focus on China’s international-relations strategy. Ari graduated with honors from Harvard with degrees in social studies and environmental science, studying in particular the geopolitics of energy and critical minerals in Latin America.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 was negotiated long before the technology to mine celestial bodies even existed. But our ability to extract celestial resources has grown exponentially since then, and the tech for a wide range of space resource activities — from asteroid mining and satellite telecommunication, to defense and space tourism — is now just decades, if not years, away from commercial-scale deployment. International law has not caught up to these developments, and negotiations to update space treaties in the United Nations have languished in the face of sticking points over dual civilian-military uses of outer-space exploration. In the absence of clear international guardrails, space-faring nations and private actors are rushing to develop the capabilities to mine lunar regolith and secure their access to valuable celestial resources.

Meanwhile, China has experienced a stunning transformation and become a space-faring nation over the past six decades. In the 1960s, China, still embroiled in the Cultural Revolution, was technologically inept, critically underdeveloped, and seemingly destined to watch from the sidelines as the United States and then-USSR battled to launch astronauts into orbit. Today, China has in most respects overtaken Russia as the United States’s chief rival in shaping international norms around conduct in the “final frontier” — and China’s increasing tech prowess has coincided with increasing assertiveness in influencing international norms and principles according to its interests.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the United States and China have gone about shaping international norms differently. Their divergent approaches have profound implications, not only in the contest for global influence, but also for national defense and the renewable energy transition — that is, requiring bountiful quantities of rare minerals.

In short:

The United States and China have both attempted to pass legislation and establish norms around outer space exploration and use within the United Nations.

When this has failed, though, the United States has continued its law-based approach, pursuing norm-building agreements and legal partnerships outside the UN system.

In contrast, China’s approach, when faced with UN setbacks, has shifted to pursuing project-based initiatives, including activities at the International Lunar Research Station.

Gaps in International Space Resource Governance

The space economy is valued at $630 billion globally, nearly doubling in size over the last decade, and is set to reach $1.8 trillion by 2035. Discoveries of water, helium-3, and rare minerals on the Moon and near-Earth asteroids have led to a surge in public and private interest regarding the mining and use of these resources.

Rights of appropriation and use are subject to significant debate in the corpus of law governing outer space. Article I of the Outer Space Treaty asserts that space is “the province of all mankind,” and all nations — regardless of developmental status — have the right to freely “explore” outer space and “use” its resources. (The drafters of the Outer Space Treaty, however, did not define the scope of the word “use.”) Article II stipulates that the Moon and other celestial bodies are “not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

Article II’s “non-appropriation” clause can be interpreted in two different ways:

As a prohibition on a state’s appropriation of an entire celestial body — ie. claiming the Moon or another near-Earth body as its sovereign territory, or

As a prohibition on claiming ownership over only celestial resources, including those extracted from the body’s subsoil. (Evidence from early drafts of the Outer Space Treaty suggests that the treaty’s drafters intended this more expansive interpretation.)

And even if space-faring entities can legally own resources they have mined, there is uncertainty about how they can legally be used:

In-situ mining entails using mining resources on the surface of celestial bodies asteroids to generate rocket propellants, energy, and life-support gasses necessary for lunar settlement and for propagating further space exploration.

There is also growing interest — and technological potential — for ex-situ resource extraction, such as bringing water, minerals, and other resources to Earth for additional processing and commercialization.

How can these disputes be resolved?

International norms often develop through customary international law. CIL “consists of rules of law derived from [1] the consistent conduct of States [2] acting out of the belief that the law required them to act that way”; the second prong of CIL is called opinio juris. CIL is developed not through written treaties between states, but through state practice. For example, when the United States first sent astronauts to the Moon in 1969, Neil Armstrong returned with moonrocks that became the property of NASA. But in 1973, Nixon ordered fragments of the samples to be distributed to 135 foreign heads of state and all 50 states. Whether Nixon’s worldwide distribution of the moon fragments developed CIL or not depends on whether Nixon distributed the fragments because he felt legally obligated to do so.

In this case, Nixon likely did not do so under opinio juris given the lack of historical precedent regarding property rights around space resources. Nevertheless, as cases of space-resource utilization become more prevalent, the paucity of clear international guardrails will both generate considerable uncertainty and present opportunities for space-faring actors to fill gaps in their stead.

The American Approach

The United States approaches outer-space norm-building primarily through promulgating domestic legislation and building multilateral voluntary codes of conduct.

Congress in 2015 passed the Spurring Private Aerospace Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship Act, or SPACE Act, which sought to address the growing liability facing private space actors. This law marked the first time any government legislated on the question of private companies’ legal right to space-resource ownership. Other countries have since followed suit. In 2017, Luxembourg passed the law “On the Exploration and Utilization of Space Resources,” which states that “space resources can be appropriated (Les ressources de l’espace sont susceptibles d’appropriation)” and also permits private corporations to explore and use space for commercial purposes. Japan, the United Arab Emirates, and Liechtenstein have also recently passed domestic space legislation guaranteeing property rights in space.

Meanwhile, the United States has leveraged its bilateral relationships to generate codes of conduct. In 2020, the United States launched the Artemis Accords, a series of multilateral agreements to build consensus and generate new international norms of conduct in outer space. The Accords seek to establish “a common vision via a practical set of [non-binding] principles” to govern the exploration and use of outer space outside of the UN system. The Accords emphasize the importance of reserving outer space for peaceful use cases, in addition to reinforcing the idea that “the extraction and utilization of space resources… complies with the Outer Space Treaty.” As of January 2025, 53 states are Artemis Accords signatories.

The Artemis Accords and domestic space legislation cannot themselves bind all states to shared rules and principles. Although the Artemis Accords are meant to shape state practice in theory, they are voluntary, and thus their influence on state activities in practice is yet to be determined. The Accords have also been criticized by key space-faring actors — such as Russia, Germany, and China — who are skeptical of attempts to act unilaterally to establish precedent over an issue of global concern. Nevertheless, although domestic laws alone cannot generate CIL, domestic space legislation may be replicated by other states hoping to foster a lucrative space industry — and these activities could generate norms that, over time, evolve into binding customs.

China’s Approach

While the United States is building customs outside the UN, China is generally committed to negotiating laws and establishing norms within the purview of formal international legal institutions. Even so, when conventional avenues for formal law-building are blocked, China isn’t opposed to operating within gray zones of international law to secure its access to critical space resources.

China has been a leader in outer-space negotiations at the United Nations, conducted mostly within the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). China is the largest voluntary contributor to UNOOSA, which allocates most of its funds to equip developing states with space data to mitigate and respond to natural disasters.

In response to gaps in international outer space law, China and Russia jointly submitted drafts of the “Treaty on Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects” (PPWT) to the plenary session of the Conference on Disarmament (CD) in Geneva. The PPWT proposed new legal instruments and a multilateral conflict resolution mechanism to prevent the weaponization of outer space, but the proposal was blocked by the United States. The U.S. representative to the CD argued that the PPWT is “fundamentally flawed,” in that it does not explicitly prohibit the deployment of space-based weapons disguised as civilian commercial activities, nor does it restrict the development, testing, or stockpiling of Earth-based weapons that can shoot down targets in orbit. Critics also noted the lack of verification mechanisms to ensure compliance — a death sentence given Russia’s abysmal track record of (not) complying with past arms control agreements.

Another point of contrast: unlike the United States’s highly law-based approach to international consensus-building, China is shaping outer-space norms through project-based initiatives:

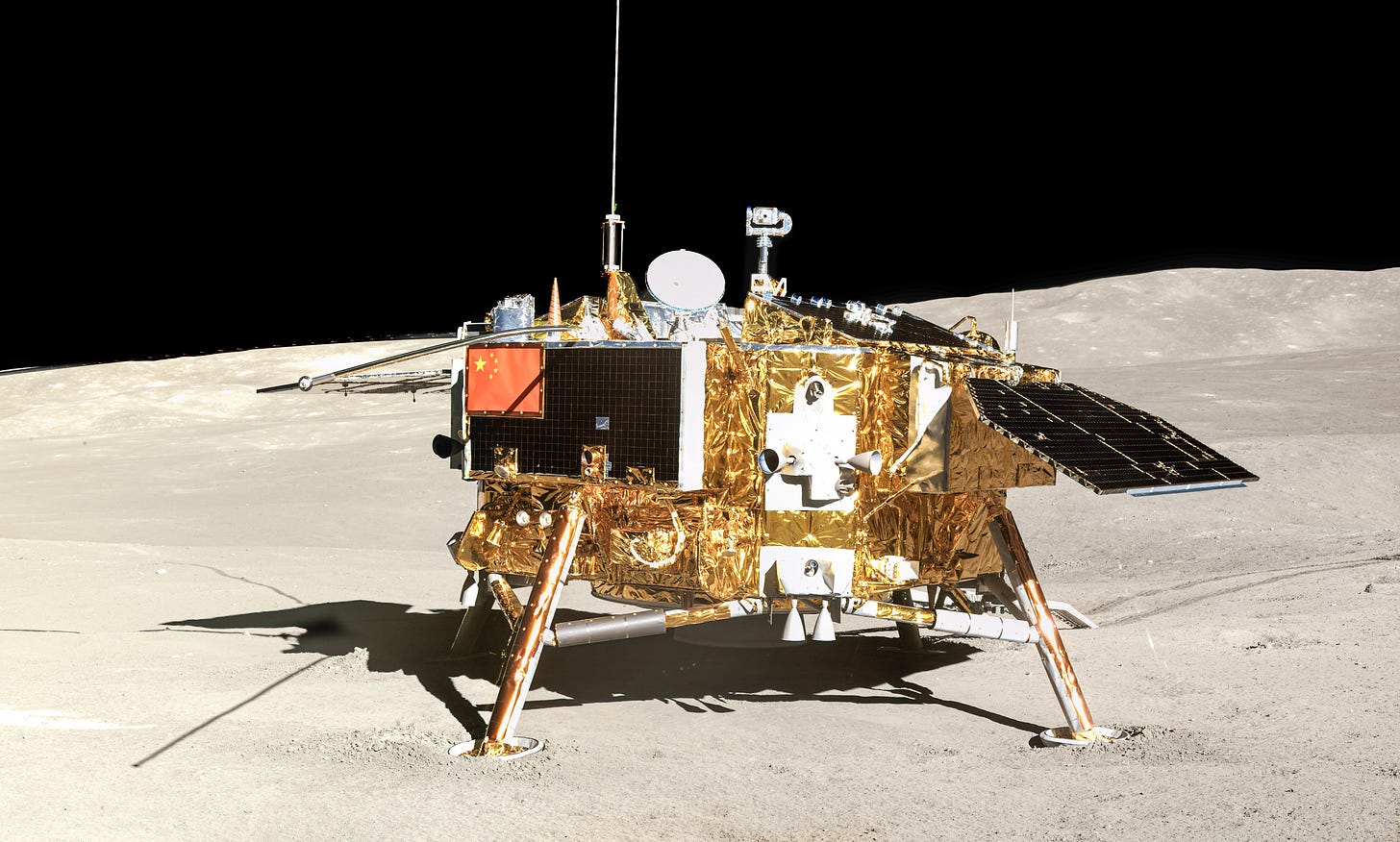

In 2004, China launched its Chang’e Lunar Exploration Program 嫦娥工程. In 2013, China successfully landed a lunar rover on the Moon — the first state to visit the Moon in 30 years. Six years later, in a historic moment, China landed a rover on the far side of the Moon, returning two kilograms of lunar regolith to Earth. The Chang’e program is an early stage of China’s long-term project to solidify a permanent economic and military presence on the Moon.

China has fostered bilateral agreements for project-based collaborations on the International Lunar Research Station. Thus far, the Chinese National Space Agency has over 170 such cooperation agreements, or MOUs, with more than 50 national space agencies and international organizations. The ILRS, on track to be finalized in 2028, will use lunar regolith to construct a base, mining ice and helium-3 to support permanent settlement.

China is not engaging in norms-based consensus building like the United States. There are no clear examples of China actively attempting to promulgate space norms internationally. China’s actions, though, will undoubtedly leave a significant footprint going forward — by being among the first to land boots on the Moon and leading project-based collaborations around lunar settlement, China will set the standard and lay the groundwork for other actors to follow.

China’s International Legal Approach in Context

What are the implications of these divergent strategies for shaping outer-space norms?

The United States is responsive to a blossoming private space sector seeking legal guarantees from their government to safeguard their capital investments. With avenues for providing those safeguards blocked at the international level, the United States has not hesitated to act unilaterally and leverage its web of alliances to develop norms toward peaceful, sustainable, and commercially viable uses of space — with or without the rest of the world on board. This strategy reflects the United States’s historical leadership in designing international law and institutions reflective of American interests, values, and free-market economic principles.

China’s outer-space strategy emerged from a different historical backdrop. China initially approached the international order as a “regime taker” in the post-Mao era, complying with laws and institutions shaped by European colonial powers. Since it acceded to the WTO in 2001, however, China has taken an increasingly assertive approach to international governance in alignment with its own values and interests. Yet, despite such increased assertiveness, the Chinese Communist Party remains at least nominally committed to promoting international decision-making within the UN system. China refers to this approach as “Upholding Multilateralism and the UN-centered International System” 维护以联合国为核心的国际体系.

China’s operations within the United Nations are strategically advantageous. The United Nations, in theory, has an equalizing effect on international law-making by providing all states with the opportunity to shape shared rules of conduct. As the self-proclaimed leader of the Third World, it’s unsurprising that China has refrained from leveraging consensus-building mechanisms outside of traditional multilateral institutions. Nevertheless, China may also uphold the UN system in service of realist aims; China has significant influence over UN decision-making as a member of the Security Council and as the world’s second-largest economy.

By virtue of China’s state-centered economic model, space innovation and commerce are highly regulated or outright owned by the state. Experts argue that China is not likely to promulgate domestic space legislation due to the risk of inadvertently restricting state ownership of valuable space resources and scientific data. China may promulgate a domestic regulatory regime in the coming decades — if economic factors and international trends toward widespread adoption of private property in space necessitate such measures.

At a fundamental level, China and the United States are realist actors working within loose international frameworks. Their strategies demonstrate not only their diverging visions for a future international order, but also diverging international imperatives. Without agreement on space-resource governance, outer space risks becoming controlled by a powerful few rather than benefiting all humanity.

Interesting angle covering the legal / rules side of Space... governance likely follows control. Incredibly important as Space and the Arctic rise in frontier prominence.

We firmly believe Space Race 2.0 is here: The Battle for AI Supremacy – ‘Space Race 2.0’ within Cold War 2.0 – composed of multiple building blocks (Semiconductors, Compute, Data, Algorithms) across multiple spheres (Arctic, Space, Ocean)...

Related piece on the rising importance of Space as a New Frontier - for Technology, Energy, & Money (collectively, Power): https://aquavis.substack.com/p/pop-space-and-the-new-frontier

As well as a summary thread: https://x.com/AquaVisX/status/1971319520603332798

I have a feeling this will be resolved by America slowly fading as a global power.

China is planning a base on the moon in the next decade. Their entire manned space program just started barely two decades ago.

America meanwhile has spent two decades and 90 billion dollars on a rocket that is supposed to fly three astronauts around the moon and back, not even landing there.