China Reacts to Export Controls

Wherefore export controls?

Last week, China’s Ministry of Commerce published new regulations governing the export of rare earths. It added five new elements — holmium, erbium, thulium, europium and ytterbium — to the list of elements under export controls. The Ministry now requires foreign companies to obtain licenses in order to export products containing over 0.1% of any of these elements or made with Chinese technology. The regulations also place a default ban on any rare earths exports destined for military use abroad, as well as applying stringent scrutiny over exports to buyers involved in manufacturing advanced semiconductors or “artificial intelligence with underlying military applications”. For more on this new chapter in the trade war, see the show we just did with the 2Chrises, former export control official Chris McGuire and Chris Miller of Chip Wars fame. Transcript, podcast, or YouTube below.

But how is China reacting to the current situation? Today, ChinaTalk rounds up leading analyses from industry experts and news media to dive further into the context behind these new restrictions. We look at:

How state media is shaping the narrative;

Why Chinese rare earth stocks rallied, and what the domestic industry thinks;

Distinguishing between the rocks themselves and the processing technologies;

And why this marks a milestone in Beijing’s approach to export regulations.

But first…we’re running our first personal classified in a minute! Michelle is a good friend of ChinaTalk who’s looking for love!

Hi! I’m a Taiwanese girl living in the Bay who loves her work, stays busy, is a homebody, and has a soft spot for all things beautiful and well-designed.

My simple pleasures: that rare text that makes me smile like an idiot.

The quickest way to my heart is: Witty banter, dressing well, forehead kisses, and good music. If you’re into Doja Cat, SZA, Tyler, or rap / chill Rnb we’ll vibe. Will that person be you? Respond to this email to connect!

State media: mining’s bad?

China’s new regulations have drawn many comparisons with the US’ Foreign Direct Product Rule and are seen as a response to American semiconductor export controls. Most commentary from Chinese state-run sources shied away from explicitly naming the US, preferring instead to describe these regulations as part of China’s pursuit of “major-country diplomacy” on the world stage. Xinhua News Agency’s op-ed on the topic opened with a rebuttal of strategic interpretations of the export controls:

Some countries’ media have labeled this move a “diplomatic card” or “strategic weapon” deployed by China amid trade frictions. Yet if we view this policy upgrade within the broader framework of global governance norms, China’s own industrial development needs, and international responsibilities, a fairer and more rational conclusion emerges: as a major global supplier of critical minerals, China is proactively aligning with widely accepted international practices, raising its governance standards, and fulfilling the responsibilities of a major power. This is not a spur-of-the-moment “tactical countermeasure,” but a step rooted in China’s deeper need for sustainable industrial development and in sync with the global trend toward standardized management of strategic resources. Its ultimate goal is the sustainable use of strategic resources and shared global development.

The People’s Daily’s Zhongsheng 钟声 column, usually seen as China’s authoritative diplomatic voice, similarly stresses that the export controls are about international security rather than US-China relations:

China has consistently fulfilled its non-proliferation obligations and responsibilities in the relevant fields, working to safeguard international peace and security. The fundamental rationale for imposing export controls on medium and heavy rare earths is to ensure that the resources are used for lawful, peaceful purposes; the measures do not target any particular country or region. By ensuring that rare-earth–related items are not used for military purposes or in sensitive domains, China demonstrates the responsible conduct of a major power firmly committed to world peace and security—an approach aligned with the shared interests of global security governance.

Interestingly, many state media reports and op-eds supporting the policy have focussed on the environmental consequences of rare earths mining. They seem to imply that with export controls, China will somehow be able to reduce the impacts of mining on Mother Nature. Also in the Xinhua op-ed:

Through reform, China is steering its rare earth industry away from the outdated model of “growth at the expense of the environment,” toward high-quality, sustainable development. In doing so, it safeguards its own ecology while providing the global supply chain with a more reliable and transparent foundation. Regulation is the path to long-term prosperity: a well-governed, environmentally responsible Chinese rare earth industry will ultimately benefit international users.

The Beijing News 新京报 (owned by the CCP’s Beijing Municipal Committee) goes even further, arguing that the environment is actually the Ministry of Commerce’s primary concern!

Beyond the necessary reciprocal responses, this round of rare-earth export controls is driven more by a holistic focus on resource conservation and sustainable development.

Rare-earth mining imposes substantial environmental costs, and prolonged, high-volume exports have continually increased China’s ecological burden. By enforcing stricter export management under the new rules, the policy aims to steer the rare-earth value chain toward higher value-added, lower-emission segments and to promote resource use that is greener and more intensive/efficient.

While rare earths are foundational to many technologies enabling our climate transition, the mining and refining of these elements do have negative environmental impacts. The process that extracts rare earths from the earth’s crust produces significant amounts of toxic waste. China, in part, obtained its world-dominating lead in rare earths mining through lax regulations surrounding the disposal of toxic waste — with severe health consequences for residents of mining areas like the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where some villages are known as “cancer villages”. Progress in making rare earth mining less harmful in China has been meaningful, but slower than ideal.

That being said, the link between controlling exports and reducing the industry’s environmental impact is tenuous at best. The regulations offer nothing in the way of actually protecting the land or people from the harms of rare earths extraction. Instead, this is probably a way for state media to set narrative guidelines domestically and frame the upcoming trade war as prosocial, in order to preemptively assuage concerns that such moves could make life harder for average Chinese people.

Industry is Annoyed

Chinese miners and refiners will find it harder to sell their products, which is probably bad news for their bottom lines. However, censorship makes it challenging for anyone to voice opposition. Some subtle references to export control violations of domestic Chinese origin can be found in this guide to compliance, published by e-commerce industry publication 勤曦运营 Qinxi Operations three days after the new regulations were published:

It’s important to note that this applies not only to foreign organizations and individuals. Even domestic operators must obtain the appropriate license if, after export, the goods remain under their actual control and they wish — once the goods have arrived in the stated destination country — to re-export them to other countries or regions, thereby changing the final destination country or end user.

In practice, there have already been multiple cases in which domestic exporters, without authorization, re-exported dual-use items that had been shipped to Country A on to Country B and were found to have committed smuggling. Such conduct is readily deemed by judicial authorities to constitute smuggling of rare earths by concealing the true export information through transshipment via a third country. Practitioners should take this very seriously: goods may still be subject to regulation even after they have been exported overseas.

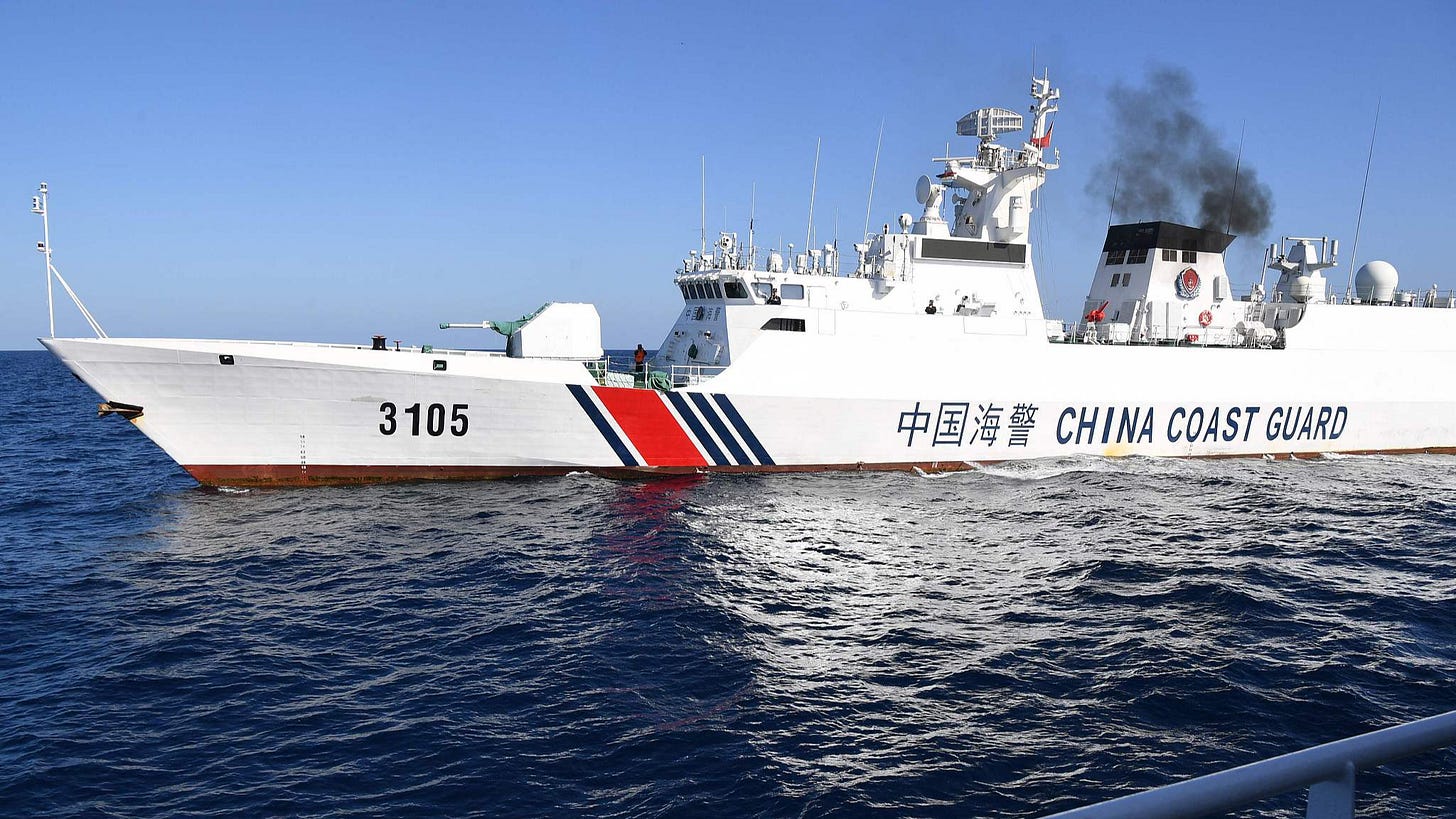

Enforcing new export controls is a multi-agency bureaucratic operation: Qinxi expects the Customs Administration, China’s Coast Guard, regional Public Safety Bureaus, and the national security apparatus to all be involved. Their guide also gives useful historical context to China’s securitization of rare earths exports:

Under Article 22 of the Export Control Law, China imposes export controls on dual-use items to safeguard national security and interests and to fulfill non-proliferation and other international obligations.

The four announcements issued on [October] 9th likewise state at the outset that the purpose of rare-earth controls is to “safeguard national security and interests” and to “meet the needs of fulfilling international non-proliferation obligations.”

This is also reflected in the control codes assigned to rare-earth-related items in the notices: the third digit in each code is “9,” indicating that these items are “related to other national-security factors.” It is thus clear that dual-use rare-earth items are closely tied to China’s national security, and the state will inevitably subject them to strict oversight. The regulatory measures being issued are trending toward increased stringency.

For example, beyond the strict control now imposed on the circulation of rare-earth items overseas (as noted earlier), in December of last year the Ministry of Commerce issued the “Announcement on Strengthening Export Controls on Certain Dual-Use Items to the United States” … The scope has thus shifted from restrictions limited to a specific country or region to an unqualified, global restriction: the target of control has moved from “the United States” to “the world.” Moreover, Announcement No. 61 uses the term “may” with respect to military end use, meaning that if regulators cannot be completely certain that a rare-earth item will not be used for military purposes, they are likely to deny a license. If an exporter proceeds without authorization, the export may constitute the crime of smuggling.

Given the wider context of unstoppable demand, CITIC’s equity research team remains optimistic about outlooks for rare earths and recommends continued strategic allocation to the rare-earth value chain. They write:

New-energy vehicles, wind power, and energy-efficient motors are aligned with low-carbon, environmental policies, and humanoid robots may become a new growth driver. We expect global demand for NdFeB (neodymium-iron-boron) magnets to reach 329,000 tons in 2027, implying a 2024–2027 CAGR of 13%.

By our estimates, the NdFeB industry’s CR4 (top-four concentration ratio) is about 29% in 2024; as leading companies bring new capacity online, we expect CR4 to rise to 42% by 2026.

Long-term perspectives on Beijing’s trade relations

Finally, some analysts have offered perspectives that place these regulations in a longer time horizon, in order to try to understand what might come next for rare earths, advanced manufacturing, and the trade war.

Ni Jianlin 倪建林 of Dacheng Law Offices, the Chinese law firm previously integrated with Dentons, wrote a blog post about the new regulations. He puts forth thoughts about China’s successful rare earths industrial policy:

Why can a single Chinese technical control leave the world’s major industrial countries on the back foot? The reason is that the core of modern industrial competition has shifted from “owning resources” to “commanding the ability to turn resources into value.”

In terms of reserves, the world is not short of rare-earth ore; the real bottleneck lies in the complex, high-barrier process chain between ore and functional materials usable in high-end manufacturing. Mining is only the starting point. The key is refining raw ore into high-purity rare-earth oxides, and then further processing them into high-performance magnetic materials for chips, electric motors, and missile systems. At present, roughly 90% of the world’s rare-earth refining and separation capacity is concentrated in China.

This pattern is no accident, but the result of more than three decades of continuous technological accumulation and policy guidance. In the 1970s, Chinese scientist Xu Guangxian developed the “cascade extraction theory,” achieving efficient separation of individual rare-earth elements at a cost just one-tenth of that abroad at the time. In the decades that followed, China kept innovating in separation and purification, environmental management, and energy-efficiency control — raising wastewater recycling rates to over 95% and overcoming the technical and compliance hurdles that Western countries struggled to clear due to high environmental costs. Today, China can achieve 99.9999% ultra-high-purity rare-earth refining and has mastered the core formulations and sintering processes for NdFeB permanent magnets, forming a closed-loop supply chain from resources and technology through to manufacturing.

Faced with this reality, the United States is not without responses. During the Trump administration, Washington rolled out increased funding and crafted plans such as the Critical Materials Strategy to rebuild a domestic rare-earth industry system. Yet these actions started too late and moved too slowly — projects typically take three to five years to go from approval to actual production — making it hard to ease supply-chain dependence in the short term. US firms have also tried to seek alternative supplies via allies such as Australia and Canada, but those countries’ output is limited, and the separation and refining steps still rely on Chinese technology and equipment.

Indeed, Chinese analyses tend to emphasize that not only does China want to flex its ability to control rare earths supplies, it also seeks to preserve its edge in refining technologies. CITIC’s report mentioned the construction of a “technological moat” for rare earths. 工业能源圈 Industry and Energy Zone, the industry-focussed blog run by Shanghai-based Jiemian News, reports on the novelty of technology-based controls in the Chinese policy context:

The “Technology Control Announcement” explicitly brings five categories of key rare-earth technologies and their carriers under control: rare-earth mining technologies; smelting and separation technologies; metal smelting technologies; magnet manufacturing technologies; and technologies for recycling and reusing secondary rare-earth resources.

According to the analysts cited, this is the first time that “technology control” [技术管控] has been clearly written into a domestic policy document.

As for the backdrop to the Announcement, they believe it is linked to current overseas efforts to poach rare-earth talent: “In recent weeks, you can see related high-salary job postings on recruitment sites in the United States, Australia, and elsewhere.” The core aim of tightening controls on technology is to achieve closed-loop controls across the entire industry chain.

The analyst further explained that China had already been controlling rare-earth items; the newly added technology controls are intended to close the loophole of “controlling items but not technology.” If foreign actors were to break through technical barriers by luring away talent with high pay, the earlier controls on items would be diluted. Therefore, the essence of technology control is to firmly regulate every aspect of the rare-earth industry chain and establish a comprehensive control system.

Excellent synopsis of the policy view and messaging from China.

https://open.substack.com/pub/thiagodearagao/p/five-things-you-need-to-know-about?r=2di31u&utm_medium=ios