Seedance, Kling and the Chinese AI Video Ecosystem

A Regulatory Puzzle

It’s been a big week for Chinese AI video.

ByteDance’s Seedance 2.0 and Kuaishou’s Kling 3.0 are going viral. Seedance probably takes the cake, being promoted for smoother motion, stronger scene coherence, and watermark-free downloads.

My favorite trend so far: people making videos of themselves cooking Lebron James.

On the other hand, the Cyberspace Administration (CAC) just announced it’s pre-Lunar New Year crackdown by removing more than 540k pieces of illicit AI content on Douyin, Wechat, and Weibo and taken action against over 13k accounts, making a statement that it’s stepping up enforcement of unlabeled or “garbage” AI-generated content.

China’s AI video ecosystem is moving at hyper-speed, while the CCP, typically the world’s most adept and overbearing content regulator, is scrambling to tighten control in real time. This is a bit puzzling, since China already has one of the most ambitious frameworks in the world for labeling and managing AI-generated content. If the rules were put in place for a moment like this, why does it feel like they’re not working?

Today:

China’s new rules for labeling AI-generated content

How those rules are being poorly enforced

The domestic incentives behind this poor enforcement, including economic growth priorities

The geopolitical incentives, including the use of AI to spread pro-China and anti-US propaganda

Part two will give a broader industry overview of how Chinese models compare to Western ones, which companies are leading and targeting the Global South, and why video generation poses different training, open-source, and copyright implications for the Chinese ecosystem.

The Rules

China was the first country to introduce rules specifically for synthetic media—the Deep Synthesis Provisions (互联网信息服务深度合成管理规定), which took effect in the dark ages of 2022.

Fast forward to March 2025: the Cyberspace Administration of China released the Measures for Labeling of AI-Generated Synthetic Content (关于印发《人工智能生成合成内容标识办法》的通知). These rules require platforms to detect when content is confirmed, likely, or even just suspected to be AI-generated, and to attach both visible labels and embedded metadata by September 1st, 2025.

The accompanying national standard GB 45438-2025 spells out what those labels have to look and sound like:

Images: visible text label covering at least 5% of the shortest side length

Audio: spoken label at 120–160 wpm, or a Morse-code-style tone representing “AI”

Video: clear labels shown at both the beginning and end of the clip

Metadata: persistent, machine-readable tagging embedded in the file

China is essentially the only major country to enact a preemptive, upstream requirement that all AI-generated video be labeled, watermarked, and traceable across the stack.

Most other countries are still operating on a reactive, harm-based model. South Korea and the UK criminalize certain uses of deepfakes if they cause harm (mainly sexual or reputational). Singapore’s Elections (Integrity of Online Advertising) Amendment Act bans deepfakes in election advertising, with penalties up to five years in prison. Russia’s Federal Law No. 32-FZ tightens criminal-code penalties for the dissemination of “false information” about the armed forces, including deepfakes or synthetic media used to “misrepresent” military operations in Ukraine. The US has little beyond a patchwork of state rules for political ads and intimate-image abuse (e.g., the TAKE IT DOWN Act), though Google and Sora voluntarily watermark their content.

The closest comparison to China is the EU’s AI Act, which mandates AI content labeling as of August 2025. However, decentralized enforcement across member states with varying regulatory frameworks will lead to fragmented enforcement across the EU, likely limiting consistent implementation.

Bending the Rules

China’s rules were supposed to take effect on September 1st, 2025. Yet if you go on Chinese social media right now, you’ll find an abundance of AI-generated videos with no labels at all.

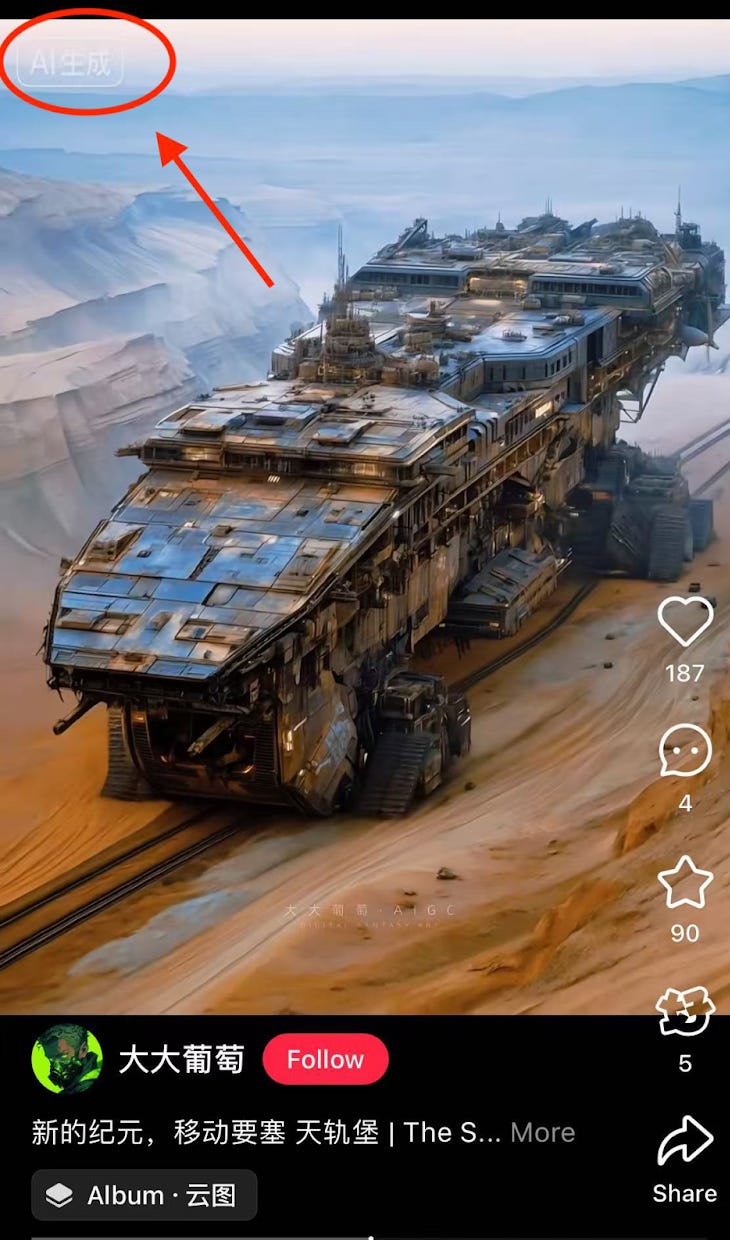

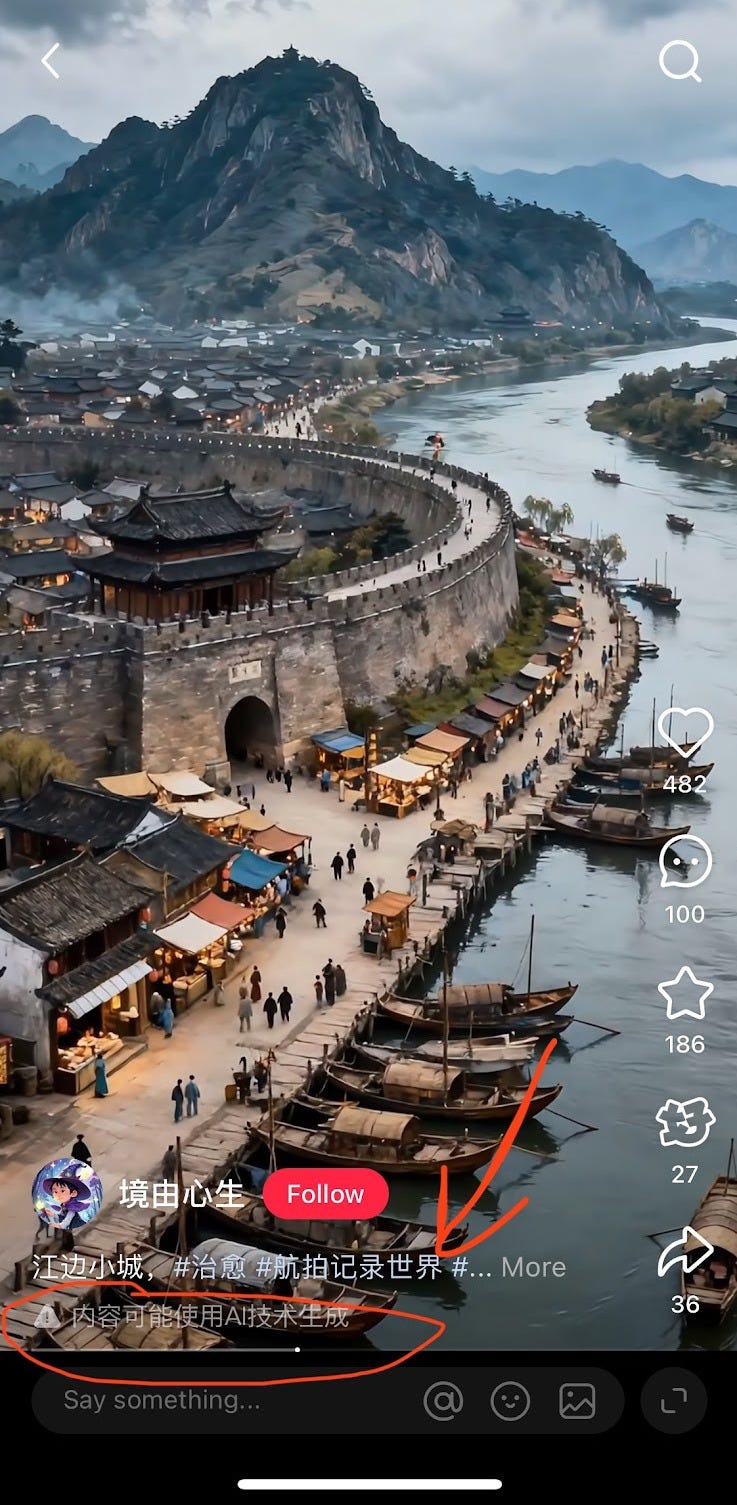

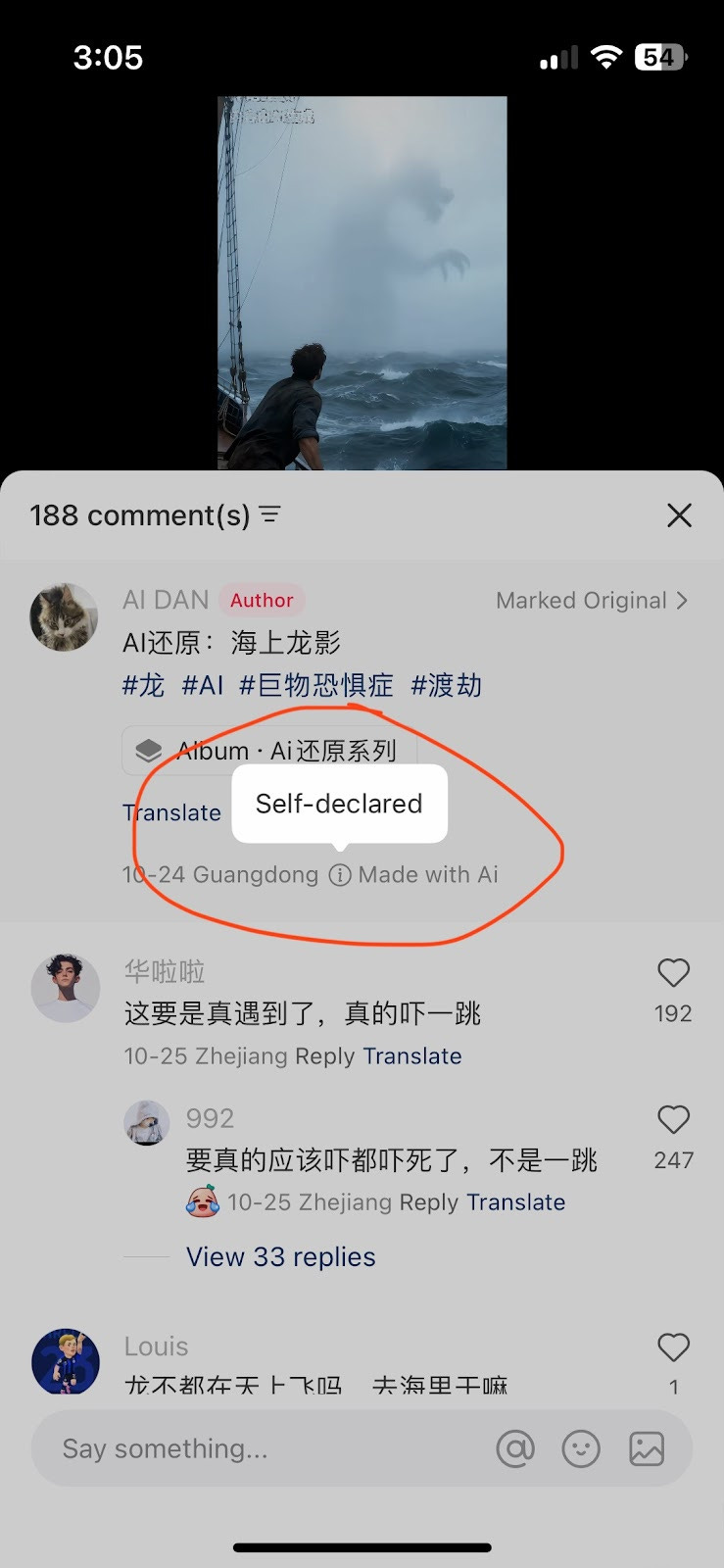

You’re supposed to see something like this label in the corner of every piece of AI-generated content:

You might also see something like this at the bottom, which reads, “This content could be AI-generated”:

Content creators can also choose to self-report when they’ve used AI:

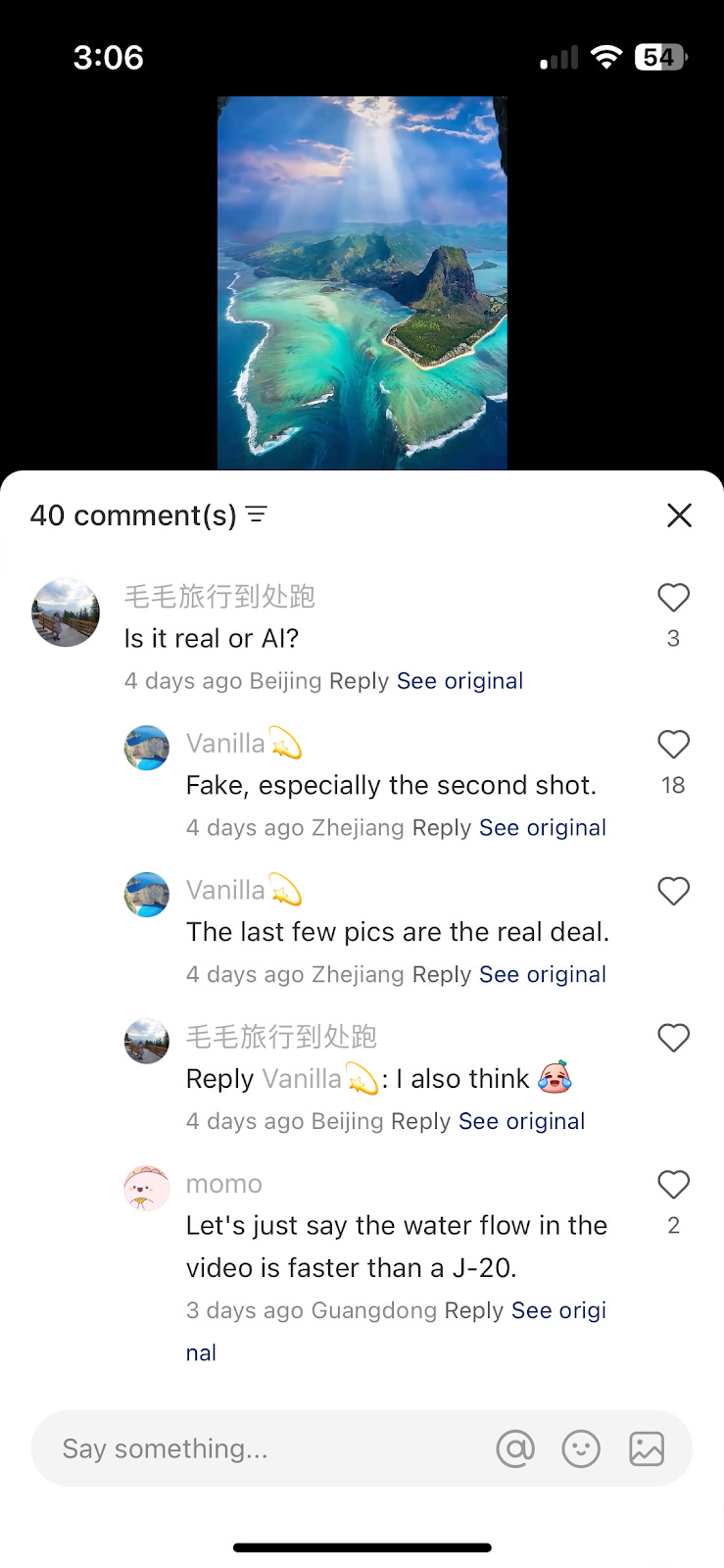

The government’s hope is that platforms will also detect this automatically through the video’s metadata. But in reality, only Chinese AI companies are beholden to including compatible identification information in their metadata, and Sora- and Veo-generated clips are quite popular on Chinese social media, usually producing the funniest content, since many Chinese models tend to avoid being subversive. Therefore, once exported and uploaded, platforms often cannot reliably determine whether a clip is synthetic. And with Chinese social media platforms locked in fierce competition, both with each other and the Western market, none wants to be the strictest enforcer while others let content flow freely.

As mentioned in the intro, the CAC says it removed more than 540k pieces of illegal AI content and acted against 13k accounts. That sounds big until you compare it to the roughly 34 million videos posted on TikTok or the 100 million throughout Meta just in one day! At that volume, 540,000 clips amount to well under 1% of a single day’s output — mathematically, a drop in the bucket.

Perhaps I’m being harsh. This announcement is meant more as a signal that the CAC is taking regulating AI content seriously rather than trying to single-handedly de-slopify the platforms. But at this scale, it risks sending the opposite message, making the CAC look less in control, not more, especially when companies like ByteDance are doing things like explicitly promoting watermark-free videos.

There is also a plethora of content online without any identification whatsoever:

You’ll commonly see AI-generated ancient towns, places in China that are subtly distorted, and landscapes that look believable enough to fool an untrained eye (all unlabeled). My mom sometimes sends me clips and asks me, “Have you been here?”

I have not.

There’s also a trend I’ve noticed of half-real, half-AI-generated content, which further blurs the precedent of whether it should be labeled. (This aligns with Part 2’s discussion of how Chinese companies are succeeding through AI-enhanced editing tools like CapCut rather than purely generative text-to-video models.) Scroll through RedNote and you’ll instantly find clips where the hill or building in the shot is clearly real footage, but the clouds shift and morph in a way that’s unmistakably artificial:

Domestic Incentives

What gives?

As Irene Zhang lamented in our Chinese AI in 2025, Wrapped:

“AI-assisted and -generated content is now so much more pervasive online than nine months ago, whether on global platforms or on the Chinese internet. It’s time to ask: what was the point of labelling as policy? Is it to actually protect users from misinformation and engender trust, or is it just a stopgap measure that lets platforms evade responsibility? What kinds of AI usage merit which kinds of mandated disclosures?”

One rationale is that China is tightening controls on misinformation while simultaneously pushing generative video as a pillar of its AI+ strategy for digital commerce and economic revitalization — a fine line to walk.

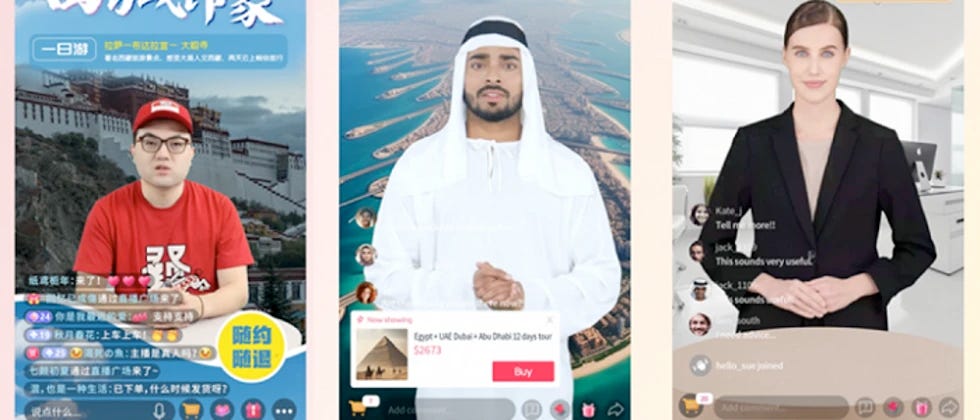

State media constantly praises AI-generated content’s potential as a new economic stimulant. The CCP is partially betting on AI video as a core part of e-commerce, short-form entertainment, and platform growth. Micro-dramas, digital-human product demos, and auto-generated marketing clips are widespread.

The government itself is generating slop. Chinese broadcasters have rolled out AI avatar news anchors, and the CCP has readily broadcast AI content through official CCTV programming; for instance, Poems of Timeless Acclaim 千秋诗颂, which uses the “CCTV Listening Media model” to transform classical poems into ink-wash animations.

Geopolitical Incentives

Those same tactics also underpin China’s AI push in the Global South, which accounts for a large share of its AI video user base. If its video-generation ecosystem restricts content too heavily, it’ll struggle to attract new users outside of China who expect the creative freedom offered by international competitors.

There have been reported cases of Chinese state actors experimenting with deepfake presenters to push pro-China/anti-US narratives in local languages, while others have promoted multilingual “AI anchors” (数字人主播) that can run 24/7 and auto-generate product videos or livestream scripts for cross-border commerce. (I was, however, only able to find a small number of documented cases of such practices, with no sign of widespread adoption.)

Beijing also doesn’t mind when the content helps give them a boost.

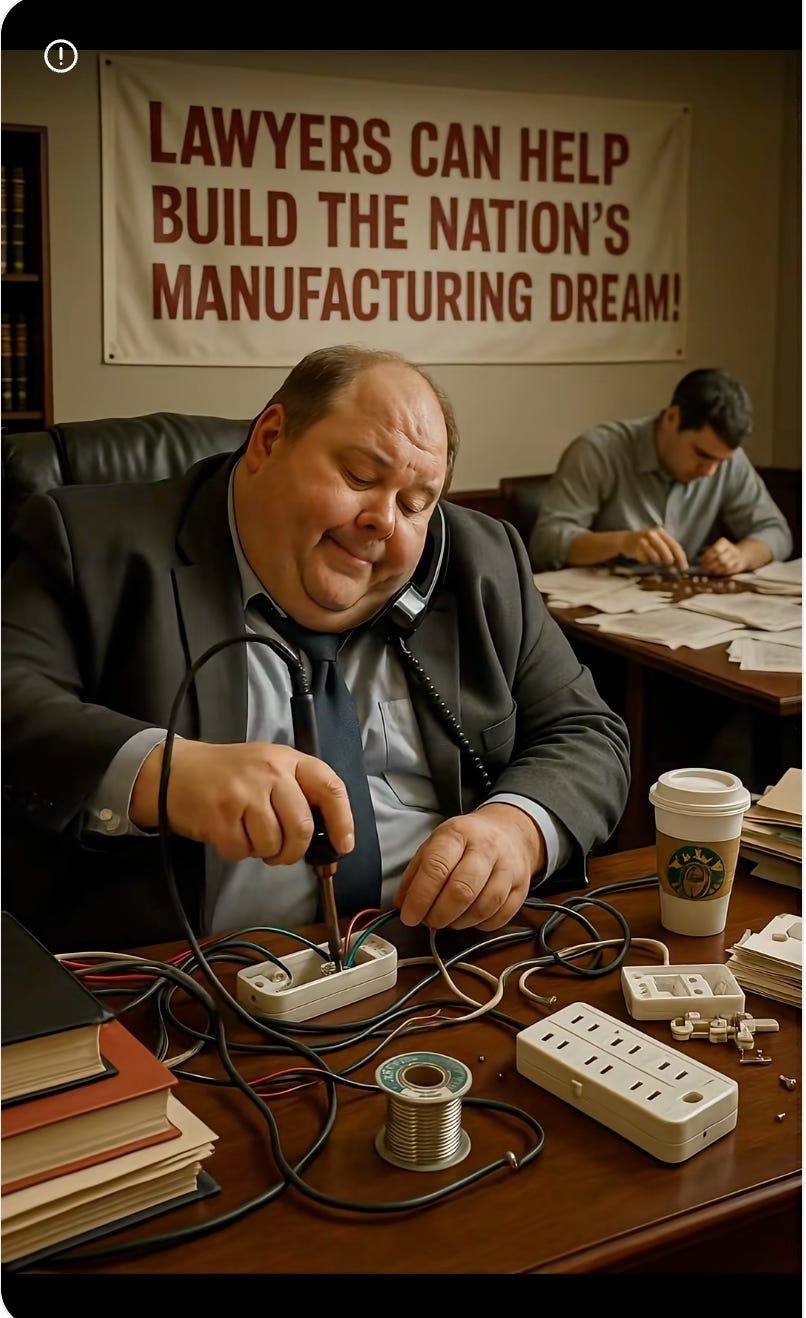

AI-generated clips that mock foreign rivals tend to circulate without much issue. This year, there’s been a wave of videos about US H-1B visa frustrations, military action in Venezuela, or overweight American factory workers struggling to revive manufacturing in the wake of Trump’s tariffs; content that flatters China’s self-image and reinforces familiar state narratives.

^A college student finally saves up enough money for her H1B visa. Source.

^‘Live-cam footage’ of US soldiers arresting Maduro. Source.

I’m not doubtful the CCP’s system is effective at blocking content it views as potentially destabilizing. You won’t find Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek sharing a beer or setting the Olympic pole vaulting world record (as I routinely do on my Instagram feed). And you’ll rarely see political dissent of any kind. But for the remaining slop, Beijing seems to tolerate a certain amount of slippage, especially if it can help grow the ecosystem and serve its other interests.

Vibe

An aesthetic observation to close.

After spending too much time on Chinese social media “researching” this article, I’ve come away thinking that AI video is seen in a more optimistic light overall than the doomerish perspective you’ll find pervading many of the comments on Western platforms.

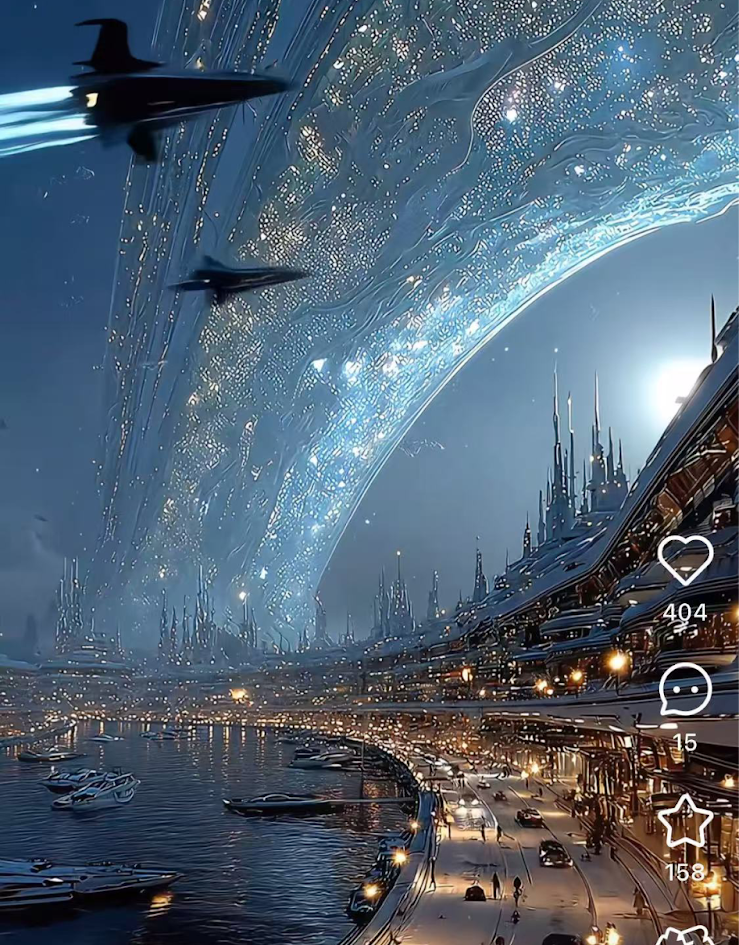

For instance, it’s quite common to find depictions of the future, often cyberpunk-esque, that fuse ancient Chinese civilization with radical future cityscapes. I’m sure this exists somewhere on Western social media beyond my filter bubbles, but it doesn’t seem as prominent.

This sinofuturistic temperament — the willingness to embrace rapid technological progress in a utopian or at least neutral register rather than an inherently dystopian one — imbues the trajectory of this technology with a greater sense of wonder. It foments an eagerness to see what worlds might be built, rather than fixating exclusively on the reality it might subsume.

Don’t worry, there’s also plenty of brainrot slop.

*Bonus clip: The ChinaTalk team tries out Kuaishou Kling’s image-to-video feature at NeurIPS 2025: