The CCP’s Taiwan Strategy

Translation of a Taiwanese government advisor on how Beijing looks at Taiwan

Ming Chu-cheng (明居正) is a retired professor of political science at National Taiwan University; he has also served in several advisory capacities for the Taiwan government.

Earlier this year, Ming appeared as a guest on the television program 年代向錢看. In this fifteen-minute segment, he discusses recent personnel changes within the Chinese Communist Party and PRC government. Then, alluding to battles fought between on the Chinese mainland in the 1930s and 1940s, he describes three strategies — Tianjin, Beiping, and Suiyuan — that the CCP may call to mind in considering how to capture Taiwan. He concludes by commenting on what he views as the mainstays of the CCP’s Taiwan strategy today, and how Taiwan and the world should respond.

Special thanks to Sharon Kuo for her translation assistance.

Three Methods to Capture Taiwan

According to the CCP’s thinking toward Taiwan, or when considering the past civil war between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the CCP, there are generally three ways to go about it: the first is the “Tianjin method” (天津模式); the second is the “Beiping method” (北平模式) [Ed.: Beiping was another name for Beijing, used especially from 1928 to 1949]; and the third is one relatively few have heard of, called the “Suiyuan method” (綏遠模式). [Ed.: Tianjin and Beiping refer to battles fought in 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War; Suiyuan refers to a standoff between CCP and KMT forces which ended in 1949.] I’ll explain these three:

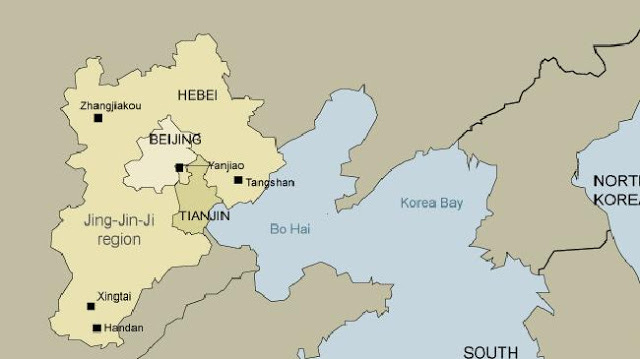

[Ed.: The above map illustrates the location and proximity of Tianjin and Beijing. The Japanese defeated KMT forces and captured Tianjin in late July of 1937; Beijing fell just days later, in early August, without further resistance.]

The Tianjin method is like what happened in Ukraine: our army invades, takes you by storm, and hopes you will be defeated or forced to surrender. That’s the Tianjin method.

The Beiping method is to destroy Tianjin, destroy your periphery, block all the escape routes of your defending troops — and then at that critical juncture (兵臨城下), force you to surrender. And what about Beiping? I didn’t start a war or begin fighting with large numbers of troops — but my troops, as it were, stood outside your city walls, forced you to surrender, and won. That’s the oft-propagandized Beiping method.

They talk about the Suiyuan method relatively infrequently. The Suiyuan method came into play when Beiping, Tianjin, and the northeast had been defeated, and the last remaining place was Suiyuan — basically an isolated island defended by an isolated army of about 60,000 to 70,000 troops, led by Dong Qiwu (董其武), then a KMT commanding officer. The CCP’s approach there was to draw a boundary line, thereby maintaining a stance of peaceful coexistence; they also kept commerce and traffic running, and from time to time made contact with the KMT. But at the same time, the CCP actively sent people to Suiyuan to convince them to surrender, in effect saying, “Look, I have wiped out hundreds of thousands of troops — almost a million — and all that remains are your 70,000. They’re useless. So how about this: you surrender, and we treat you well?” Dong Qiwu surrendered after a few months. That’s the Suiyuan method. (For what it’s worth, after Dong Qiwu surrendered, he eventually achieved the rank of general in the PLA.)

[Ed.: Above is a map of ROC administrative divisions from 1911 to 1949. Note that Suiyuan is to the northwest of Hebei, in what is now eastern Inner Mongolia, PRC; Suiyuan is not literally an island.]

Now the CCP is dealing with Taiwan. Its stance today is similar to a combination of Suiyuan and Beiping: “We mutually draw boundaries, at least orally maintain a peaceful coexistence, as far as possible keep traffic and commerce open, maintain communication — but we actively try to convince you to give in.”

But in achieving the next step, [the CCP should note that] today’s Taiwan situation is not the same as the Suiyuan or Beiping of the past. Back then, international factors obviously weren’t important. Even though [initially] the United States actively mediated [during those conflicts], eventually it gave up — which the CCP certainly noticed. Today, however, the United States, Japan, Europe, and other important countries all pay extremely close attention to Taiwan. So today’s strategy toward Taiwan can’t only take into account the Beiping or Suiyuan methods — it needs to consider international factors, too. So as I just said, Wang Yi’s role here is very important, because he is an important handler in international Taiwan-related matters.

So with that all in mind, what is [the CCP’s strategy] toward Taiwan?

The conversation continues with Ming explaining:

What is ultimately today’s CCP strategy toward Taiwan;

What factors will drive a decision to invade;

How the US and Taiwan should respond to reduce the chances of war;

How to read the tea leaves of recent government personnel shifts.