The Long Shadow of Soviet Dissent

Disobedience from Moscow to Beijing

To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement — the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Professor Ben Nathans — is the sharpest, richest, and funniest account of the Soviet dissident movement ever written. Today, we’ll interview Nathans alongside the legendary Ian Johnson, whose recent book Sparks explores the Chinese dissident ecosystem.

We discuss…

The central enigma of the Soviet dissident movement — their boldness in the face of hopeless odds,

How cybernetics, Wittgenstein, and one absent-minded professor shaped the intellectual backbone of post-Stalinist dissent,

Why the Soviet Union was such fertile ground for dark humor, and why humor played a vital role for Soviet resistance movements,

How the architect of Stalin’s show trials laid the groundwork for, ironically, a more professional legal system known as “socialist legality,”

Similarities and differences between post-Stalinist and post-Maoist systems in dealing with opposition,

Plus: Why Brezhnev read The Baltimore Sun, how onion-skin paper became a tool of rebellion, and why China’s leaders study the Soviet collapse more seriously than anyone else.

Listen now in your favorite podcast app.

The Dissident’s Playbook

Jordan Schneider: I want to start with the title. It’s pretty much the best title I’ve ever come across because Soviet jokes are the best things that exist in the twentieth century. Where did it come from and how did you choose it?

Ben Nathans: Long after all the physical remnants of Soviet civilization have deteriorated into dust and no physical traces are left of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Soviet anecdotes — or anekdoty (анекдоты) — will remain as the single best, most compact and pungent guide to what that place and time was about. I couldn’t agree with you more about Soviet humor.

I deserve no credit for the title of the book, “To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause.” It’s literally borrowed from a toast that dissidents would make, typically sitting around kitchen tables in cramped apartments in Moscow, Kyiv, Leningrad, and other cities. For me, besides the sonic resonance of that phrase, it captures with amazing efficiency the central enigma of that movement and these people — their ability to be bold and despairing at the same time.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s take it back to the death of Stalin. None of what happens in this book — the court cases, personal dramas, and legal maneuvering — happens in a Stalinist Soviet Union because if anyone plays around with this stuff, you’ll get shot or go to the Gulag and no one, much less Amnesty International, ever hears from you again.

Let’s talk about that transition and why those who came after Stalin decided to take a different approach than Stalin to political dissent.

Ben Nathans: Whenever you have a system where power is highly concentrated at the apex of society and where the personality and predilections of the ruler are so decisive — and this applies in many ways to modern China as much as it does to the Soviet Union — “biological transition events” (fancy language for the death of the leader), are fraught with uncertainty.

It’s worth remembering that the Soviet system really was formed under Stalin. During his twenty-five years in power from roughly 1928 to 1953, the fundamental characteristics of the system came into focus and were fixed, not in the sense of made better, but anchored and became more or less stable.

To speak to your question directly — the reason why things changed so fundamentally after Stalin’s death in March of 1953 is that the system of state-sponsored political terror, the use of state resources to go after real or perceived enemies, was incredibly damaging to the political elite itself. The riskiest position you could occupy under Stalin was to be a high-ranking member of the Communist Party. What was really dangerous was to be a member of the security apparatus, because many of the people who were carrying out political terror fell into the vortex of this enormous punitive machine themselves, or they committed suicide because of the psychic stress of having to sign death warrants for thousands of people.

If only as a matter of self-preservation, Stalin’s successors decided that this system could not continue and it needed to somehow stabilize itself. When you look back at the twentieth century and ask what leaders or what systems were most effective at killing communists, it wasn’t Hitler’s Germany — it was Stalin. Stalin killed way more communists than Hitler did. It’s also possible that Mao killed more communists than Stalin did. Ian would have to weigh in on that. It’s worth keeping in mind what kind of autocannibalism this system was capable of exercising.

Jordan Schneider: Ian, can you draw a parallel to how the post-Mao leadership began thinking about ways to prevent the political system from becoming a complete blood sport?

Ian Johnson: The parallels and the differences are quite striking. While I was reading the book, I kept thinking how it was similar but also different to China. In China, everything was delayed until Mao died in ’76. There was no real de-Maoification in the way there was under Khrushchev with de-Stalinization. People say the main reason for this is that for the CCP, Mao was Lenin and Stalin rolled into one. You couldn’t get rid of Mao without calling into question the entire revolution, whereas that could happen in the Soviet Union.

There was a push for a bit of de-Maoification in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but it wasn’t sustained. The structure of the system may have changed in the ’80s and ’90s, but the guts of the repressive system was still there. You end up with something quite different in China than what happened in the Soviet era under Brezhnev.

Jordan Schneider: Now is maybe a nice point to introduce Volpin, perhaps the century’s most impactful autist. What a character this guy was.

Ben Nathans: Alexander Volpin was a Moscow-based mathematician, who ended up becoming what I describe as the intellectual godfather of the dissident movement. He was the absent-minded professor to end all absent-minded professors, someone who was famous for walking around Moscow in his house slippers, who had an extreme interest and ambition for what cybernetics could do for the world. Cybernetics was the movement unleashed by the MIT professor Norbert Wiener in the 1940s and ’50s that attempted to translate every known phenomenon into the language of algorithms. It’s a clear predecessor of computer science and software engineering.

Jordan Schneider: Which also has an afterlife in China and is famously the intellectual superstructure for the one-child policy.

Ben Nathans: It also has an afterlife in the United States, where algorithmic attempts to refashion society, human life and human beings themselves — that impulse is very much alive in certain pockets of the United States today.

Volpin was not just a mathematician, but a mathematical logician, which is to say he was interested in the nature of truth statements in mathematics and how we know that this or that given proof is rigorous or not. He also was a keen student of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Wittgenstein’s quest for what he called “an ideal language.” This goes back to the analytic philosophy movement that was centered in Oxford in the interwar period. Wittgenstein was an Austrian Jew, but he made his way to Oxford and made his first mark in the United Kingdom.

Ideal language philosophy is based on the idea that many philosophical problems stem from the messiness and ambiguity of the language we use to think. Human languages like English, Russian, and Chinese are just inherently messy. They use one word to describe many different things, some of them having nothing to do with each other. For example, the word “patient” can mean the person who a doctor sees, but it can also be an adjective meaning someone who has the capacity to wait without getting agitated. There may be some deep Latin-based etymological connection between those two, but for all intents and purposes in English, that one word performs multiple, essentially unrelated functions. This is an example of how human languages are just really bad for thinking clearly.

Volpin’s quest was to develop a language that would be free of those ambiguities and lack of clarity. He obviously looked at mathematics as the gold standard for clarity and rigor when pursuing truth or trying to make statements about reality. But he, like everybody else in this movement, including Wittgenstein himself, ultimately failed to come up with an ideal language that could fulfill those criteria of clarity and rigor.

Over the course of his life in the Soviet Union under Stalin, he, like tens of millions of others, had a number of nasty encounters with the police, the secret police, the broader punitive apparatus, and, in his case, with the practice of sending certain inconvenient people to psychiatric institutions against their will. These run-ins with the Soviet legal system were deeply traumatic and difficult for him to process.

But he had a lot of time on his hands, while in prison and in exile in Central Asia, in Karaganda in Kazakhstan. One of the things he spent time doing was reading the Soviet Constitution and the Code of Criminal Procedure. To his surprise, he found a parallel attempt at an ideal language — something most legal systems strive for. The goal is to clearly map out what you are allowed to do, what you are required to do, and what is forbidden: the three fundamental moral categories

Having failed, along with everybody else, to produce an actual algorithmic ideal language, he realized that Soviet law was a plan B for this quest. He gradually developed this approach that if the Soviet government could be held to its own laws, which he thought were actually pretty good, the civil liberties that were enshrined in the Soviet Constitution and the various procedural norms that were encoded in the code of criminal procedure — things would be a lot better.

This became the disarmingly simple grand strategy of this movement, which was: make the government honor its own laws. We’re not out to change the government, we’re not out to topple the government, we’re certainly not out to seize power ourselves. It’s impossible for me to imagine someone like Volpin running anything because of how abstract and literal his thinking was. He was not a social creature. But this quest for the rule of law in a society that had gone through some of the worst episodes of lawlessness and state-sponsored terror. This became the master plan for the movement.

Jordan Schneider: Ian, from a personality perspective and strategic perspective, what echoes did you see in the Volpin story to what you covered in China?

Ian Johnson: Interestingly, Ben mentioned in his book that this was picked up by other Soviet satellite states, especially in Eastern Europe. Notably, it was also adopted in the ’90s by the Chinese rights defense movement, the Weiquan movement (维权运动). This core idea — if activists hold the government to its laws, they can’t be easily labeled as subversive or counter-revolutionary. They’re not trying to overthrow anything, to subvert the state. This approach was largely successful for the movement and its lawyers for about fifteen years, roughly from the late ’90s to the early 2010s. While the dynamic shifted later, we can see clear parallels between the Chinese movement and its Soviet counterparts.

Significant foreign funding and NGO support were channeled into this movement, creating a small industry focused on rule of law dialogues, judicial training, and legal workshops. This strategy was partly inspired by the perceived success of similar initiatives during the Soviet era, leading many to believe a comparable development could occur in China.

For a period, it did. A flowering of civil society emerged, for about a twenty-year-period, if you want to be optimistic, from the 1990s into the early 2010s. However, the party abruptly decided this was ridiculous, and they cracked down on the movement in a notably more severe way than the Soviet authorities had done.

Ben Nathans: I’m interested in whether what you described is a function of Soviet-style regimes producing a specific kind of opposition movement. One that favors the rule of law, one that is essentially conservative and minimalist rather than revolutionary and innovative. Or were there actual lines of influence? Were people reading texts produced by the Soviet dissident movement or coverage of it, where we could really talk about cause and effect rather than just typological repetition?

Ian Johnson: Well, they were very influenced by the Czech movement. For example, a very well-known public intellectual in China named Cui Weiping (崔卫平) — she’s a film critic and activist – translated many things by Václav Havel which were widely read. They weren’t published in China, but they circulated in a Chinese version of samizdat (самиздат).

In the Soviet Union, you had the old-style samizdat where somebody hammered through multiple pieces of carbon paper to copy it, and then others made more copies. In China, the movement took place during the digital revolution, so they simply made books or magazines into PDFs and emailed them.

While they were influenced by the Soviet movement, I don’t know whether the construction of the rule of law was influenced by the Soviets. I wonder if any authoritarian states, Soviet-style or not, have to rely on laws to some degree because society is too complex otherwise. Not everything can be decided by the party secretary. You have to have some kind of legal system for disputes among companies or minor issues between people.

A quick word from the sponsor of today’s episode:

Jordan Schneider: Smita, a friend of the pod and co-founder of Alaya Tea, has successfully lured me away from Chinese to Indian tea this past month. Smita, how is your tea so good?

Smita Satiani: Thanks, Jordan. I'm glad you’re liking it. We started Alaya Tea in 2019 because we learned that most of the large box tea brands that you purchase are actually getting their teas from layers of middlemen, brokers, and auction houses in India. They typically sit for a couple of years in warehouses before we get to drink them.

We started Alaya because we wanted to go directly to the source and cut out many of those middlemen. We get our teas directly from tea estates and farms. They’re all regeneratively and organically certified, and we do multiple shipments a year, to ensure you get the freshest cup of tea. It’s also only loose leaf, so we leave all of the dusty tea bags behind.

With loose leaf, you're actually getting a full leaf tea. When you brew it and steep it, it unfolds in your cup, and you get so many more flavors that you normally wouldn't taste in a ground, bottom-of-the-barrel tea bag. The last big thing is that it's plastic-free. There are no microplastics, which are often in tea bags, so you don’t taste any plastic. There’s no plastic in our packaging either.

Jordan Schneider: I love the Assam black tea in particular — I’ve been making milk teas out of it all week, and it’s been fantastic. Go to alayatea.co and use the code CHINATALKTEA for free shipping.

Smita Satiani: Enjoy!

Jordan Schneider: Ben, could you talk a little bit about going from revolutionary justice to more boring justice with laws and statutes?

Ben Nathans: That transition happens, at least aspirationally, in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. This transition was overseen by an unlikely figure — Andrei Vyshinsky, who was Stalin’s Minister of Justice. He was the architect of the infamous show trials in Moscow, in which some of the most prominent Old Bolsheviks – people like Nikolai Bukharin who had been close to Lenin and had been members of the party long before the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 – appeared on witness stands and confessed to the most outlandish crimes. They confessed to spying for Great Britain, Nazi Germany, and Japan, often simultaneously.

These confessions were entirely scripted and detached from reality; nearly all defendants were subjected to torture or threats against their families. These tactics are the hallmarks of show trials.

But the irony is that Vyshinsky, who oversaw these trials, was also the person who essentially oversaw the transition away from revolutionary justice toward a more professional legal system, which he called “socialist legality."

Revolutionary justice is the idea that you don’t need professionally trained lawyers the way bourgeois societies do, societies that place much of the legal decision-making process in the hands of people who have degrees, pedigrees and credentials from elite, usually conservative, educational institutions. Revolutionary justice holds that real Justice — capital-J Justice — flows most profoundly and reliably from the instincts of people who are on the right side of history: members of the working class. You don’t need professional jurists. What you need are workers whose gut instincts about right and wrong are the most reliable (some have said infallible) means to decide guilt or innocence.

In the 1920s, the most revolutionary period of Soviet history, all kinds of experiments were being carried out — some breathtaking, others absolutely horrifying. During this time, revolutionary justice was seen as the highest form of adjudicating issues in courts, applied in everything from divorce cases to questions of political justice, high, low, and everything in between.

But the Bolsheviks soon learned that revolutionary justice was really unpredictable. Workers did not always produce the results that the party leadership wanted or expected. As in many other arenas, by the 1930s, Soviet leaders began to retrench. They decided it would actually be a good idea to have professionally trained judges — people who could retain certain standards of legal procedure, including precedence, the proper use of evidence and what a confession should look like.

The actual practice of justice was nothing like what we would call professional. These show trials were travesties of justice according to Western standards. But we have to bear in mind — and Ian will be able to speak to this in the Chinese case — that the term show trial itself is often used condescendingly, like this is all just pretend, this is a bullshit trial, this is not real justice being meted out, this is all scripted in advance. The Soviets called it pokazatel’nyy protsess (показательный процесс), which translates more accurately to “demonstrative trial.” A demonstrative trial had a pedagogical goal: to teach the population about right and wrong and, above all, about the state’s power to punish the guilty.

Once we move away from the condescension that the term “show trial” conjures up, we’re in much more complicated terrain. Western legal systems are also engaged in the business of teaching. That’s why trials are public. It’s not just that the actions of the prosecution, defense, judges, and to some extent the jury can be subject to scrutiny. It’s because trials are also classrooms where certain lessons about right and wrong are broadcast and where state power is on display.

It’s much more complicated when you realize that Vyshinsky was presiding over a transition away from revolutionary justice. It wasn’t just about these farcical show trials — it was also about a Soviet version of a professional judiciary.

Jordan Schneider: The Chinese echoes of this are fascinating. On one hand, you have revolutionary justice meted out in land reform and Cultural Revolution struggle sessions. Then sometimes you’re dealing with malfeasance like the Gao Gang case in the mid-1950s behind the scenes. But most famously with the Gang of Four, where Deng said, “No, we’ve got to put these guys on TV and show everyone that we’re never going back to the Cultural Revolution.” More recently, Xi put Bo Xilai (薄熙来) on trial. I don’t think it was live-streamed, but there were definitely clips of that trial that circulated for instructive effect.

I’d like to ask Ian for any other thoughts.

Ben Nathans: Ian, how successful do you think these overtly pedagogical, spectacular trials were in China? In the Soviet case in the 1930s, most people seemed to believe the defendants were guilty of the insane crimes to which they confessed.

Ian Johnson: That’s a good question. I’m not sure exactly how much people in China believed what they were seeing, but the government certainly used similar tactics — holding trials in football stadiums, staging mass trials and public executions, and forcing people to attend.

But for those who attended — I think it’s a universal human tendency to believe that there must be some truth to a statement someone makes. Where there’s smoke, there’s fire. Maybe it’s exaggerated a bit, but it’s got to be somewhat true. It can’t be all made up.

That mindset likely held during cases like Gao Gang’s in the 1950s and others from that era. But sometimes these trials elicited a different reaction — solidarity. I remember an example from 1960 involving one of the students who published the underground magazine Spark (星火). She attended a show trial in Lanzhou, in Gansu Province in China’s far west.

The famous filmmaker Hu Jie (胡杰) later interviewed her for a documentary. She recalled being deeply moved by the defendants — by the way they held themselves, by their refusal to concede to making any mistakes. She found their dignity inspiring. So I wonder whether, at least in some cases, the spectacle backfired — eliciting sympathy rather than submission.

Ben Nathans: The trials of the dissidents in the ’60s backfired to a great degree. Ironically, the government was actually much more responsible about the kinds of evidence that it introduced in these trials, and they didn’t torture any of the defendants. They didn’t even beat them. It’s weird to think that the procedurally more respectable trials were less convincing than the stage-managed show trials of the ’30s.

A Hysterical Day in Court

Jordan Schneider: The split screen of 1960s Chinese Cultural Revolution stadium denunciations and executions, and then what we’re about to talk about with Sinyavsky and Daniel — this kind of absurdist comedy of two writers — is something to keep in mind. Ben, why don’t you transition us from Volpin to this literary scene, which has its completely hysterical day in court?

Ben Nathans: Yes, in both senses of the meaning of hysterical, very funny and also nuts. Volpin has this strategy that he’s developing privately, and you can find the evolution of his thinking about the legal strategy in his diaries, which are housed in the archive of the Memorial Society in Moscow. I worked with them when one could still do that, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Volpin loved to write a long entry on New Year’s Eve every year. He was big into taking stock and taking account, not only reviewing what had happened the previous year, but setting out goals for the next one. In one entry, I think it was 1958 or ’59, New Year’s Eve, and having arrived at this legal strategy, he says in essence, “I’m just waiting for the right opportunity to put this into practice.”

That opportunity arrived in the fall of 1965. This is one year after Khrushchev had been yanked from the top position as General Secretary of the Communist Party, allegedly for mental health reasons, but the real reason was that the rest of the party elite couldn’t stand how unpredictable and erratic his policies were. Khrushchev had been out of power for a year and everyone was wondering: What comes next? Are we going back to Stalinism? What kind of future can we imagine for this country that has just gone through this epochal transition away from mass terror?

When these two figures — Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel — were arrested in September of 1965, it sent shockwaves through the intelligentsia because this seemed very ominous. Many people had not heard of these guys and were unaware that they had been publishing short stories, novellas, and essays under pseudonyms outside the Soviet Union — all completely hush-hush. When it came to light that they had been arrested and were going to be charged with anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, there was a kind of panic: “This is the first sign of a return to the kind of repressive state that we knew in the 1930s and ’40s under Stalin.”

Volpin decides this is an occasion not to demand the innocence of these writers, not to insist that they be released from custody, but simply to apply the demand of the rule of law to this particular case. They were arrested in conjunction with each other because they had been operating together. They used the same person to smuggle their works abroad.

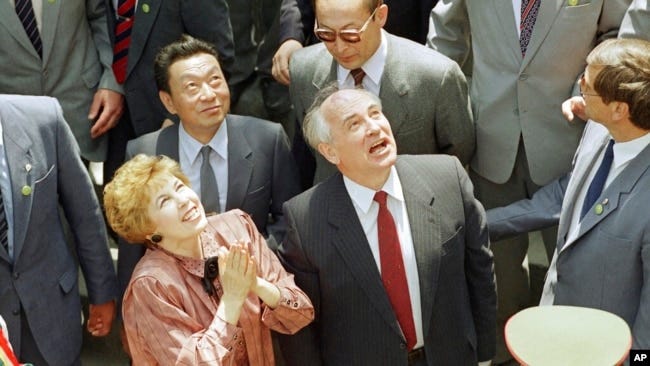

He came up with something that had never before happened in Soviet history, or anywhere else. That was organizing a meeting in the name of transparency — a meeting for glasnost (митинг гласности). The word itself is not new. It goes back at least to the 19th century, maybe even the 18th century. It means transparency, publicity, or openness. People of a certain generation are very familiar with this word because it was one of Mikhail Gorbachev’s key words during the glasnost era — the era of transparency and reformation, perestroika. But Volpin was the one who mobilized the word in a new way, as a way of responding to the arrest of these two writers.

The demand of the meeting that he was going to call was very simple: an open trial for these two writers and everything in accordance with the Soviet Constitution and the code of criminal procedure. Nothing more, but also nothing less.

In the book, I detail how, in fits and starts, the planning for this glasnost meeting — this transparency meeting — came into focus. It’s an absolutely fascinating story, and in some ways it was, for me, parallel to the histories that have been written about the coming into existence of the Declaration of Independence. It’s a slightly grandiose analogy because the Declaration was the launching pad for not just a new country, but a new kind of political system. But people have done fantastic work on the various drafts of the Declaration of Independence, not only by Thomas Jefferson but by other authors. And I tried, in my own small way, to do something similar for the opening salvo in what would become the Dissident Movement — namely, this appeal to Muscovites and others to meet on December 5th 1965, which is the anniversary of the ratification of the Soviet Constitution, to make this very minimalist demand: open trial.

You can watch Volpin’s thinking evolve in real time over the course of the fall of 1965. Even more interesting, you can watch other people enter what was originally a kind of monologue on his part, entering the conversation about this new rule-of-law strategy. There was enormous skepticism, not to mention just derision of this idea. Most people’s initial response to Volpin’s approach was: “Are you nuts? Have you lost your mind? This government doesn’t care about law. Why are you being naive, thinking you can use Soviet law against the Soviet state?” It’s counterintuitive to take Soviet law seriously because everyone grew up thinking that it was just window dressing.

Volpin’s response to those criticisms was always: “You’re part of the problem. There are too many people like you who don’t take law seriously and who aren’t ready to hold the government accountable when it breaks the law. If there were more people like me who insisted on the literal application of the law — not only to the behavior of Soviet citizens but to the behavior of the Soviet state — we’d all be much better off.”

Ian Johnson: Let me ask you: Why did the government agree? Why didn’t they just make these people disappear? Why did they feel this need to conform? Was it because they were concerned how it would come across in the West, or was there something else going on internally?

Ben Nathans: I think it’s both. First of all, this was a government, not only under Khrushchev, but also under his successors (principally Leonid Brezhnev, who governed for the next 20 years), in which all of these leaders shared Khrushchev’s sense that they couldn’t go back to Stalinism. It was just too lethal, and above all, too lethal to the party elites themselves. Everybody wanted stability and predictability, and the new benchmark of success and power was no longer, “How are we doing compared to tsarist Russia, say in 1913 on the eve of the First World War?” That’s a fixed benchmark — it’s not changing over time. But under the conditions of the Cold War, the comparative framework was always, “How are we doing in our competition with the United States?”

The United States was not set in amber. The United States was probably the most, or at least one of the most, dynamic societies on the planet. To be able to claim that the Soviet Union was getting closer and closer to generating the kind of wealth that the United States could generate and was superior to the United States in the way it distributed that wealth required certain forms of predictability, of stability at the top of the system, and of the ability to satisfy the needs of the Soviet population. That’s why you have creeping consumerism in the Soviet Union starting in the 1960s.

Part of why the Soviet government didn’t just execute Sinyavsky and Daniel is that it wanted to showcase itself now on a global stage — that it could compete and essentially outcompete its rival. But there were also internal reasons that have often been overlooked.

In Stalin’s time, the name of the security apparatus was the NKVD. This is the predecessor to the KGB, the name that everybody is familiar with, if only because Vladimir Putin himself was a KGB agent. KGB stands for the Committee for State Security (kомитет государственной безопасности).

This is the crux of what you’re getting at, I think. The KGB itself wanted to become more professional, more modern. It wanted an image of a professional kind of intelligence service that didn’t keep dungeons and torture chambers for its victims, but was fully consistent with modern governance. That’s why the dissident trials of the 1960s and to a lesser extent in the 70s demonstrate how the Soviet system was really trying to have modern professional trials, not show trials. They don’t torture the defendants in advance. They don’t hand them a script and say, “This is what you’re going to say.”

Now it’s true that the judges and the prosecution are always working together, but that’s not specifically Soviet. That’s the way most continental judicial systems work. It’s the United States and the Anglo-American world with an adversarial system that’s the outlier historically.

The Soviet Union was trying to have a professional judicial system. It wanted to broadcast an image of itself around the world, not just to the West, but to the newly decolonizing states in the developing world that faced this kind of choice. There’s a fork in the road: Are we going to go the American route — capitalist, multi-party systems — or are we going to go the Soviet route — socialist economy, a planned economy, single-party rule? One of the ways of competing is to show that you have a modern judiciary with procedures that everyone can respect.

So there are performative elements, but there are also internal elements that have to do with the attempted self-professionalization by the KGB.

Jordan Schneider: It’s hard to do. You have this great closing metaphor in the book of stage and actors playing their parts, with some people who don’t want to play their parts. This dance between what’s real and what isn’t, and how much you want to commit to the bit, creates a lot of tension throughout the book.

Volpin picked a great test case. Sinyavsky and Daniel played their role to the T and were on a very different script than what the prosecutors and judge had any idea they were going to go up against. Granted, if you pick some absurdist, creative fiction writers pushing the bounds of form to put on trial, then maybe you should be ready for the unexpected.

This trial was my favorite of the ones you profile. What were they called in for? What were the facts?

Ben Nathans: The facts are that for the course of nearly 10 years, these two were publishing works abroad using pseudonyms, and the KGB took a decade before it could figure out who the actual authors were. It’s an amazing detective story. The initial thought was, “These are émigrés who harbor this lifelong, biographically driven grudge against the Soviet Union because it destroyed tsarist Russia, the country they grew up in and loved.” So they hunted for émigrés. As you know from current events, when the Soviet intelligence services decide an émigré is acting against the interests of Moscow, they’re not shy about going after them no matter where they live.

But they couldn’t find émigrés. They also started to think, “Whoever these guys are, they write about Soviet reality with such incredible specificity and tactile familiarity. Maybe they’re living inside the country because they seem to know this system from the inside out.” Their humor and satire was on target. It was hard to believe someone who doesn’t live here and know the system intimately could produce this kind of fiction.

They’re looking all over, and it literally takes them 10 years before they crack this case. Meanwhile, Andrei Sinyavsky had been working as a literary critic and an instructor at the Gorky Institute for World Literature. One of the most delicious ironies in this story is that in its attempt to ferret out who the real authors were, the KGB actually shared some of its classified material with the faculty of the Gorky Institute. The thinking was that these guys really know literature, and maybe their stylistic analyses of these pseudonymous publications abroad can help with this investigation. Sinyavsky was literally being consulted about his own case at one point. I can’t imagine what was going through his mind when this happened.

Yuli Daniel was less well known professionally. He worked mostly as a translator in his day job and produced satirical stories, which are amazing. If I may be permitted a brief detour, one of Daniel’s stories is called “Murder Day.” It’s a counterfactual science fiction story about an experiment that the Bolshevik leadership runs in the early 1960s.

The idea is that the Bolshevik revolution is not just about creating a more just society. It’s not just about abolishing private property and greed and selfishness and cultivating collectivism and solidarity. Ultimately, it’s all for the creation of a new kind of human being — Humanity 2.0. People who will have been born and grown up under this new system will have different characters from people who grow up under capitalism. That’s the most radical agenda of the Bolshevik Revolution: to create new kinds of human beings, not just a new kind of society.

Daniel’s story runs with this idea and imagines a day in the early 1960s when the government declares that murder is now legal because it wants to find out: What do these new human beings do when there are no institutional constraints on their behavior, there’s no sword hanging over their head saying, “If you kill someone, you’re toast”? They’re going to remove that entire incentive and disincentive structure and see how people behave. Will the new Soviet person refrain from this most heinous of crimes if left to their own devices without the threat of punishment? The story plays that out. It’s just this amazing, not just thought experiment, but a way of thinking through the Bolshevik experiment and wondering if it actually succeeded in creating new kinds of human beings?

Needless to say, the Soviet government didn’t like this. It didn’t like anybody saying anything satirical or funny about it.

Sinyavsky and Daniel are eventually found out. It’s like a whodunit detective story that involves analysis of the typewriters that were used to disseminate their stories. It turns out the conduit to the West for their stories was none other than the daughter of the French naval attaché at the embassy in Moscow — a woman who’d formed very close friendships with both Sinyavsky and Daniel and others, named Hélène Peltier. She went on to become a professor of Slavic literature in France. She eventually married someone and took on a different last name, Zamoyska. But this is an amazing story of a kind of platonic smuggling love triangle, and then the whole thing unravels and these two writers are arrested.

You mentioned the trial itself. Thanks to the wives of the two defendants, particularly the wife of Yuli Daniel — a woman who had a PhD in linguistics, Larisa Bogoraz, who went on to become, I would say, a more important dissident than Daniel himself (and we can talk about her later, and also why it’s the men who became famous rather than the women in general) — she and the wife of Sinyavsky, a woman named Maria Rozanova, as spouses were permitted to enter the courtroom. That was a small form of transparency that the state allowed.

They were able to create verbatim transcripts of the trial, and those transcripts were eventually reproduced under the technique known as samizdat, which is just a Russian neologism that means “published it myself.” What it means in reality is people with typewriters, carbon paper, and onion skin paper just multiplying — like a chain letter — a text of anywhere from 1 to 500 pages. The transcripts of these trials started to spread around the Soviet Union. They were also smuggled abroad and published in all of the major European languages as well as Japanese, I believe.

These trial transcripts were dynamite. Like a lot of historians, we all want to bring our protagonists to life. We want to create, within the realm of the factually verifiable, stories that bring the past to life. We want to do what the great historian Bill Cronon described as carving stories out of what is true. At some point it hit me when I was working on this book: I have dialogue that I can reproduce in my book. I don’t have to make up people talking to each other. I actually have dialogue that was captured in two forms — trials (the back and forth between the prosecution and the defendants or the witnesses) and interrogation transcripts (the dialogue between the interrogator and the victim or the witness in any given case). It’s a dream come true for a historian to be able to say, “And then he said, and then he said, and then she said,” and it’s literally something you can document.

To make it even better, I discovered something when I was working at the archive of the Hoover Institution in California at Stanford. For all these years we’ve known that the two wives created this transcript of the trial, and that transcript has been read very widely — people have written about it. But always in the back of my mind was: How accurate is that transcript? Larisa Bogoraz was a linguist, she was very skilled at shorthand note-taking, but we have no way of knowing whether that is a full and accurate record.

Then I found the KGB dossier on Andrei Sinyavsky at the Hoover Archive. During the early post-Soviet period, any dissident or the descendant or spouse of a dissident had the right to request a copy of their KGB dossier. Andrei Sinyavsky did this for himself, and after he died, his widow, Maria Rozanova, sold that dossier to the Hoover Institution.

There is — talk about a Eureka moment — amazing material in that archive. Interrogation records from before and during the trial. But among other things, I found that the government produced its own transcript of the trial. If you look carefully at photographs during the trial, you’ll see that on the defendant’s dock where Sinyavsky and Daniel are sitting are two things that look a lot like microphones. I’m pretty sure that the KGB was making a recording of the trial. The plan was that they would release the transcript in an attempt to damn the defendants.

But they were kind of rookies at trials that weren’t scripted. They were rookies at trials where the defendants hadn’t been tortured in advance. What they got with this recording was: “Oops, this is a transcript that really doesn’t make us look good. It makes the defendants look good."

The key point is that I compared the official transcript, which had never been released, with the one that was created by the wives of the defendants. Lo and behold, the transcript that circulated in samizdat and eventually in the West was about 95% accurate. It was extremely close to a transcript that was made from what I am convinced was a tape recording. In some cases, the unofficial transcript was more accurate because it recorded the audience reaction — there are moments where it says “stormy applause” or “grumbling in the audience.”

Jordan Schneider: It’s like stage direction.

Ben Nathans: Exactly. It’s just like “you are there” text. I can’t make up anything better than this transcript. It’s like the interrogation transcripts — I can’t do better than that. This was a dream.

Jordan Schneider: I think we owe it to them to do a little reading session. Here are my two favorite excerpts from this. This is the interrogator speaking — “The majority of your works contain slanderous fabrications that defame the Soviet state and socialist system. Explain what led you to write such words and illegally send them abroad.”

The defendant responds, “I don’t consider my works to be slanderous or anti-Soviet. What led me to write them were artistic challenges and interests, as well as certain literary problems that troubled me. In my works, I resorted to the supernatural and the fantastic. I portrayed people who were experiencing various maniacal conditions and sometimes people with ill psyches. I made broad use of devices such as the grotesque, comic absurdities, illogic, bold experiments of language.”

The interrogator continues, “In the court session and in the collection published under the title ’Fantastic Stories,’ the Soviet Union is described as a society based on force, as an artificial system imposed on the people in which spiritual freedom is impossible. Is it really possible to call such works fantastic?”

The defendant replies, “I don’t agree with this evaluation of my works.”

It’s brilliant because he’s getting the interrogator to essentially admit that what he’s saying is true — that the Soviet Union is a crappy place to live.

Ben Nathans: Yes, there are many layers going on here. But I want to push back a little against what you said earlier. The purpose of Sinyavsky’s and Daniel’s self-defense — and they’re amazingly eloquent when they’re on the stand — was to make the case for the autonomy of the literary imagination. They were trying to say that literature is outside the sphere of ideology, politics, and also the law. That’s very different from what Volpin wanted to make out of this trial.

The two writers in the dock were trying to assert the freedom of the literary imagination — in other words, to defend the vocation of the writer of fiction. What Volpin wanted to show was how the government couldn’t put together a consistent legal case and how important it was for the details of this trial to be made known to the public.

Even though Volpin wasn’t the one who arranged for the codification and dissemination of the unofficial transcript, the people who did came up with a very clever strategy. The trial lasted roughly three days. What they did was punctuate the unofficial transcript with coverage in the Soviet press. You’d have day one of the trial — here’s what was said verbatim by the judge, witness, defendants, prosecutor, whatever. Then here’s what the Soviet press said about the trial for all the tens of millions of Soviet citizens who couldn’t be there.

When you saw this juxtaposition and how warped and skewed and tendentious the Soviet media coverage was, the effect was devastating. Anybody who read this could only conclude that the Soviet media was a completely unreliable reporter on what had actually happened in this trial. It was a devastating document in its time.

Jordan Schneider: One more excerpt on the literary aspect. This is the judge speaking to Daniel — “You wrote directly about the Soviet government, not about ancient Babylon, but about a specific government, complaining that it announced a public murder day. You even named the date, August 10, 1969, right? Is that a device or outright slander?”

Daniel responds, “I’ll take your example. If Ivanova were to write that Sidorova flies around on a broomstick and turns herself into an animal, that would be a literary device, not slander. I chose a deliberately fantastic situation. This is a literary device.”

The judge asks, “Daniel, are you trying to deny that ‘public murder day’ supposedly announced by the Soviet government is in fact slander?”

Daniel replies, “I consider slander to be something that at least in theory, you could make other people believe.”

Ben Nathans: Yes! If you find it credible, you’re an enemy of the Soviet state. But if you recognize it as fantastical, like I do, then you’re not. Brilliant argument, absolutely brilliant.

Jordan Schneider: This tactic of making the system risible — are there parallels in the Chinese context that come to mind?

Ian Johnson: In some ways the avant-garde artists in the 1990s were trying to achieve that with some of their art, but I don’t think there’s anything quite the same as what happened here.

It made me very envious because I kept thinking, “These are such colorful characters and there’s such a richness of data that you have because of the archives being open, at least for a certain amount of time — enough time to get the stuff out in a way that hasn’t happened with China.” Perhaps we’ll see stuff like that happen in the future.

Ben Nathans: It’s actually, as always with humor, a seriously interesting subject — why things are funny, what makes them funny, what context allows these things to be perceived as funny. The question for me is: was it the absurdity of the Soviet system that generated so much dark humor?

Jordan, first of all, I’m delighted that you picked up on the funny parts of the book, because it would be tragic if that got missed. But I want to be clear: it’s not only dissidents that made jokes about the government and the Soviet system. Joking was pervasive. This was a very widespread coping mechanism and also a meaning-generating mechanism.

I could rattle off any number of Soviet anecdotes that have nothing to do with dissent per se, but are meant to capture the absurdity of some aspects of life in that system. My favorite one is: “First learn to swim, then we’ll fill the pool with water.” (“Учимся плавать…нам воды нальют.”) This captures the out-of-sync-ness of so much of the patterns of life in that country.

When I tell these jokes to my students at Penn, the result is usually a sea of blank faces. The minute you explain a joke, you have executed that joke, and it loses its frisson or energy. These are culturally specific jokes, but what they capture is profound and deep.

I don’t know enough about Chinese culture to say, but there’s some combination of the predecessor to the Soviet Union — namely the Imperial Russian substratum — and the absurdities of the Soviet way of organizing society that produced this bottomless reservoir of dark humor. It really is the thing that I think will abide after all the other traces of that civilization are gone. The humor will still be there.

Jordan Schneider: There’s just this aspect of earnestness that you see in the Chinese post-imperial political tradition where... perhaps this is a ChatGPT query. I’ll try to find the funniest stuff written by Chinese people about Chinese politics. But none of the dissidents today are particularly funny in the Chinese context.

Ian Johnson: Chinese people, of course, are funny and they love to tell jokes, but there’s this phrase in Chinese, “you guo you min” (忧国忧民) — “worrying about the nation, worrying about people”. One is essentially a Confucian official, concerned about the country and concerned about people, and therefore it’s your duty to do this, as opposed to this scallywag, ne’er-do-well aspect that comes out a bit in the Soviet era.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, you have Taoist holy fools, but the Taoist holy fools aren’t there to make fun of the emperor. They’re just there to be drunk and have a good time.

Ben Nathans: It’s worth noting that when the Soviet dissident movement was covered in real time, above all by Western journalists, they almost never mentioned humor. People like Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn were not perceived as having any sense of humor. It’s only when you start digging below the surface, and especially into the memoirs and the diaries and the letters and other less well-known sources, that you realize there is this substratum of coping through humor and satire. It’s very deep.

Ian Johnson: That’s a good point because when journalists are trying to sell the story, they’re trying to sell it as a big serious story about people standing up to authority, and humor doesn’t fit into that narrative well.

Disseminating Defiance

Jordan Schneider: Ben, let’s take it back to this incredible trial of these authors. How does anyone end up hearing about it? How does this get disseminated?

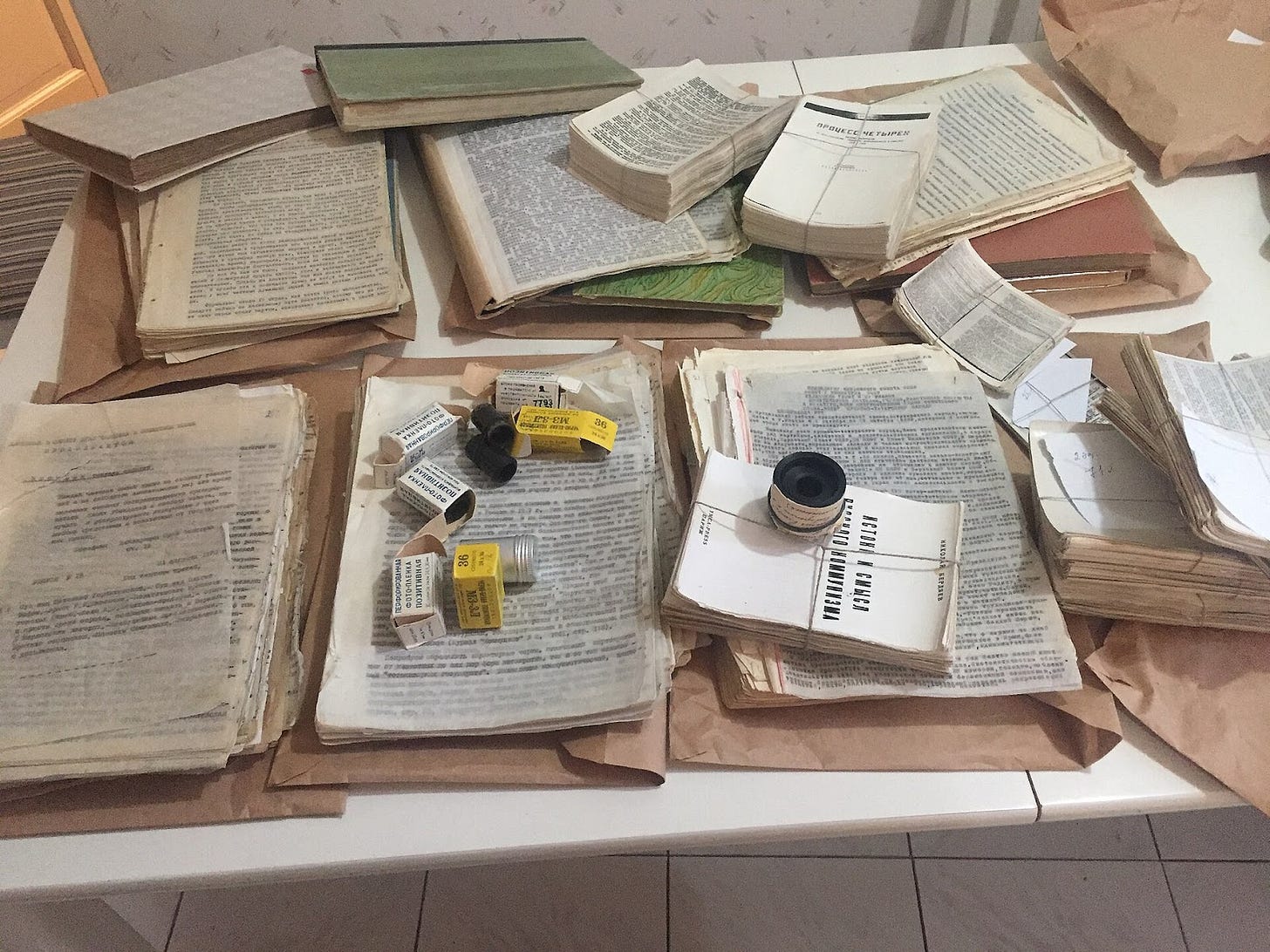

Ben Nathans: Samizdat (Cамиздат) is a DIY technology where people create copies of restricted literature in their bedrooms. The two wives of the defendants produce their own unofficial transcripts. They do this day in and day out over the course of the trial. Eventually it becomes part of an anthology of documents — the transcript of the trial, coverage by the Soviet press, letters from various observers. It circulates through this technique known as samizdat, which is just a Russian neologism that means “I published it myself.” The implication is: I never could have published this in any of the state-sponsored publishing houses, where everything has to pass through the censor’s office.

The technique is almost unbelievably simple. All you need is a typewriter and very thin, preferably onion skin paper, and carbon paper. You create a stack of alternating onion skin and carbon paper. It could be three deep, five deep. Some people say it could be as many as 10 or 12 sheets deep. You wind it around the platen in your typewriter and you pound on the keys. When you’re typing, you’re actually making three, five or ten copies of the document. One of the typists said that by the time you finish typing a novel on samizdat, you’ve got shoulders like a lumberjack because you’re just pounding the keys.

Then it disseminates the way a chain letter disseminates. You give one copy of this text to someone and that’s essentially a gift. You’re saying to that person, “I’m allowing you to read this uncensored text which is technically illegal” — although that’s a gray zone — “and could get you into trouble.” In return for the favor of granting you access to this forbidden fruit, you yourself have to create multiple copies of it and distribute it again to people who you trust.

It seems very primitive, but a couple of things were happening around samizdat that made it much more efficient than it might first appear. One is that samizdat texts were often — not always, but often — smuggled abroad, and a certain proportion of those smuggled texts were taken up by publishing houses in the West. They were either translated and published for Western readers or translated by an émigré press in Russian or Ukrainian or Lithuanian or whatever indigenous Soviet language they’d been composed in. Typically they would be published in small pocket-sized editions and smuggled back into the Soviet Union in a technique known as tamizdat (tamиздат), which means “published over there."

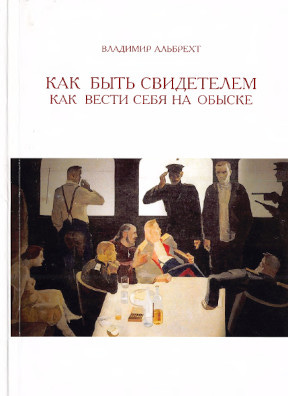

I have an example that I purchased years ago of this little book. It’s a handbook for dissidents or anybody who thinks they might be called in for an interrogation by the KGB. It’s by another mathematician named Vladimir Albrecht, and it’s called How to Be a Witness (Как Быть Свидетелем). It’s literally a manual for: “What do you do? What do you say? What do you not say? How do you say it?,” if you get hauled in by the KGB in a trial. It’s a fantastic book, well worth reading now. In fact, it’s been reproduced on the internet in Russia now for protesters starting in 2011, who also were getting hauled in by the KGB’s successor, the FSB.

Tamizdat significantly amplified the reach of samizdat publications. The true power emerged when these smuggled samizdat texts reached the research divisions of shortwave radio stations broadcasting to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. This included broadcasters like Voice of America (which Trump is in the process of obliterating), Radio Free Europe, the BBC, Deutsche Welle, and Kol Yisrael. Many foreign countries used shortwave radio to broadcast what we would now consider audiobooks.

Samizdat texts themselves were typically homemade books, crudely bound perhaps with a paperclip. The networks involved in producing and distributing samizdat encompassed tens of thousands of people. I can say that with some confidence because the KGB did my research for me in this case. As you can imagine, there was no institution in the world that was more interested in the dissident movement and in what it was doing and producing than the KGB.

The KGB conducted an incredibly thorough investigation of the most popular underground samizdat periodical, A Chronicle of Current Events. Their findings demonstrated that samizdat was available in every medium to large size Soviet city, from Moscow to Vladivostok, across all 11 time zones. They compiled lists of tens of thousands of individuals involved in these distribution networks — people who were creating, distributing, or just reading samizdat. That’s a significant number of people.

When considering “radizdat” (radio publishing through shortwave radio stations), then we’re talking about millions, probably tens of millions of listeners. I don’t know that we’ll ever be able to calculate the number of Soviet listeners, but the anecdotal evidence from diaries and memoirs is overwhelming that this was a very widespread phenomenon all across the Soviet Union.

These distribution networks start looking a little less backward and inefficient than they might at first glance. Between 2000 and 2010, in the heyday of the internet when all kinds of utopian aspirations were being read into the internet and what it would do in terms of creating a globally transparent information society, people liked to say, “Oh, the internet is the samizdat of the 21st century. It leaves samizdat in the dust because now we’re talking about billions of people able to communicate below the radar screen with unmediated contact to each other. Isn’t that wonderful?"

Well, it turns out that in some ways samizdat was far superior to the internet. The most obvious way is that samizdat was an ownerless technology. Nobody owned it. There was no platform belonging to Meta, Google or to anybody else. That meant samizdat couldn’t be disrupted, controlled, or censored in the way internet platforms are — and trust me, the KGB tried many times. In that respect, while it may be technologically backward, it was far more effective as a medium for true freedom of expression.

Jordan Schneider: I want to read my two favorite paragraphs of your writing in the book that describe the experience of what it was like to be a samizdat reader and creator:

“Samizdat provided not just new things to read, but new modes of reading. There was binge reading: staying up all night pouring through a sheath of onion-skin papers because you’d been given twenty-four hours to consume a novel that Volodia was expecting the next day, and because, quite apart from Volodia’s expectations, you didn’t want that particular novel in your apartment for any longer than necessary. There was slow-motion reading: for the privilege of access to a samizdat text, you might be obliged to return not just the original but multiple copies to the lender. This meant reading while simultaneously pounding out a fresh version of the text on a typewriter, as a thick raft of onion-skin sheets alternating with carbon paper slowly wound its way around the platen, line by line, three, six, or as many as twelve deep. “Your shoulders would hurt like a lumberjack’s,” recalled one typist. Experienced samizdat readers claimed to be able to tell how many layers had been between any given sheet and the typewriter’s ink ribbon. There was group reading: for texts whose supply could not keep up with demand, friends would gather and form an assembly line around the kitchen table, passing each successive page from reader to reader, something impossible to do with a book. And there was site-specific reading: certain texts were simply too valuable, too fragile, or too dangerous to be lent out. To read Trotsky, you went to this person’s apartment; to read Orwell, to that person’s.

However and wherever it was read, samizdat delivered the added frisson of the forbidden. Its shabby appearance—frayed edges, wrinkles, ink smudges, and traces of human sweat—only accentuated its authenticity.75 Samizdat turned reading into an act of transgression. Having liberated themselves from the Aesopian language of writers who continued to struggle with internal and external censors, samizdat readers could imagine themselves belonging to the world’s edgiest and most secretive book club. Who were the other members, and who had held the very same onion-skin sheets that you were now holding? How many retypings separated you from the author?”

Ian Johnson: That really demonstrates a fact of civil movements or civic movements — that it’s smaller groups that are bound together in some way that have a much more lasting impact. The problem with social media is it’s good at creating a straw fire. Let’s all go out to protest, to “take down Wall Street” or whatever it is, but two months later, how many people are still with you? After somebody gets arrested, who’s with you? Immediately people drop away. But people who are bound in this collective act are much more likely to have some impact.

Jordan Schneider: It was scary, but also fun, exciting, and cool. They’re all hanging out together, drinking till five o’clock in the morning. It was a lifestyle in a way that just being on Twitter and posting is not. Because there was this thrill of the chase and excitement.

Ben Nathans: To the list of qualities that you just mentioned, I would add something essential to this movement from start to finish: the intense adult friendships that kept these face-to-face communities together and the kinds of trust and loyalty that those friendships entailed. These are meaningful things in any setting, but they are especially meaningful in a setting like the post-Stalinist Soviet Union where the level of public or social trust was really catastrophically low.

People were afraid of informers and people who might denounce them, whether they were neighbors or co-workers. The counterpart of these little islands of trust and friendship among men and women in these groups was a high degree of suspicion and cynicism about society as a whole. Those are legacies that are still at play in Russia today. They were certainly enabling for the dissident movement, because to engage in these kinds of activities — which could get you arrested, could prevent your children from ever getting into a university — you really had to trust the people that you worked with, whether it was on drafting a document or taking part in a demonstration or simply housing and disseminating samizdat texts.

Those were really important qualities, and the intensity of friendship and trust within the movement had a dark side which made the movement rather elitist. It made the participants skeptical of people that they didn’t know. One of Volpin’s criteria for success for these demonstrations was always, “Did I see people there that I don’t know?” Because he wanted that. He recognized that to become an actual social movement, one needed to move beyond these circles defined by friendship and intimacy. But that was easier said than done. For many people, the suspicion of strangers never went away, and they preferred to work in small groups with a lot of mutual knowledge and the ability to work together creatively.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting because on the one hand, unless you can have a chain reaction — real exponential growth — it’s hard to have real change. But on the other hand, for a lot of these people, what triggered them down this path was the KGB putting them into a position where they had to start incriminating their friends. That was the ethical fork in the road. Most people chose to comply, but for a handful of folks who became the core among the thousands who challenged the system, that was the thing that brought them to a moment of truth about how they were going to relate to the regime.

Ben Nathans: Yes. It’s what I call, and I borrow this from Andrei Sinyavsky himself, the “moral stumbling block.” It could take many different forms. For someone at the elite level of the system like Andrei Sakharov, this great physicist who was the architect of some of the Soviet Union’s most lethal nuclear weapons, the stumbling block was when he realized that he was going to have no say about how those weapons were used, including how they were tested and the environmental damage that resulted from the above-ground testing of nuclear weapons.

But for many people it was more like what you described, where they’re brought in to the KGB in whatever city they live in and they’re told that they are going to become informants for the KGB and they’re going to have to tell the KGB in weekly or monthly meetings what their friends are up to. For some people that was such an ethical crisis that they couldn’t live with themselves if they adopted that role. Yet they were loyal citizens; they had been brought up to respect the KGB as the protector of the revolution. These created crisis moments. Most people ended up making their peace with the system, adjusting to it. But for certain very high-minded Soviet citizens, that was morally impossible. Those are the people who sometimes found their way to the movement.

Jordan Schneider: In the post-Stalinist context, you’re not getting shot, but this is not costless. There are lots of examples in your book of people losing their jobs, people being sent away from their kids, of not being able to care for elder relatives. It’s still a very aggressive step to take, even though the KGB is not going to take you behind the shed.

Ben Nathans: Yes. All of those things that you mentioned are terrible. They disrupt lives, they ruin lives. But to really assess their historic significance, you have to see them in comparison with the kind of punishments that were meted out under Stalin. Under Stalin, the people who populate my book would have been shot. These dissidents would have been shot in dungeons in the KGB headquarters in Moscow and in the various provincial headquarters, or they would have been sent to the gulag for hard labor for up to 25 years.

The last thing I want to do is whitewash the punitive system under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, but it’s a sea change from what preceded it. That was noticed by the dissidents themselves. Sinyavsky writes about his interrogation based on his own father’s experience that he was expecting to be beaten and possibly tortured. Instead, he describes the KGB agents who interrogated him as astonishingly polite. They’re trying to get him to talk.

“Redder than Red” Dissidents

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about someone who had some gulag stripes, Grigorenko. There’s a really interesting parallel with the line he takes, because a fair number of folks in China also have this “redder than red” justification for their issues with the regime.

Ben Nathans: Early on in the history of both of these regimes, the typical worldview of someone who became a protester or a dissident was Marxism-Leninism. They held this idea that the regime had somehow jumped the tracks and was no longer living up to the ideals of the revolution. This, after all, was Mao’s great criticism of the Soviet Union after Stalin: that it had somehow slipped into a very pernicious form of revisionism, and that Khrushchev, under the guise of de-Stalinization, was actually turning the Soviet Union into a reactionary bourgeois country. Therefore it was incumbent upon Mao and China to take up the banner that Lenin had led and to become the vanguard of the world socialist revolution.

Similarly, domestic opposition in the Soviet Union in the 1940s and 50s generally advocated a return to Marxism and Leninism. It’s when that ideological worldview starts to run out of gas, starts to lose its energy and its mobilizing capacity, that a space is opened up for a new approach. That new approach is the legalist philosophy, which is much more minimalist. It’s not about toppling the regime, it’s certainly not about any kind of revolution. Volpin and other rights defenders were fed up with revolutions and their accompanying violence. They wanted incremental, fully law-abiding change.

Someone like Grigorenko was a convinced Leninist. It’s only very late in life, after he has played out his part in the dissident movement and has been forced to leave the country and settle in New York, only then does he really adopt a new worldview of Christianity and give up the Leninism that he had advocated for most of his professional life, both in the army and as an important member of the dissident movement.

Ian Johnson: That’s really true for China as well. A lot of the people would always talk about reading or ransacking the collected works of Marx and Engels for the footnotes, because that was their way of finding out more about Western philosophy and outside ideas. It was inspiring to them as well, but in different ways.

Ben Nathans: Somebody should do a history of the various modes of reading Marx, Lenin, and Mao. It’s a particularly good group of authors to do such a study for because their works were produced in mass state-subsidized editions of tens of millions. That means that we have an unusually large readership. The work of the historian will be to recapture the nature of those readings and the receptions of those works.

Any work that has even a minimal level of complexity lends itself to different ways of reading and misreading or creative misreading. This would be a fantastic case study of texts that were read by millions, maybe billions of people. They’re a touchstone for how people read — what they make of a given text in any given time and place.

Jordan Schneider: It makes you feel for Xi Jinping printing all those books with no one reading them. I want to do a reading from some of the Grigorenko transcripts. This is the prosecutor saying: “We’re not here to lead a theoretical discussion. You created an underground organization whose goal was to topple the Soviet government. Fighting against that is the task of the organs of state security, not of party commissions.”

"That’s an exaggeration,” he responded. “I didn’t create an organization with the aim of violently overthrowing the existing order. I created an organization for the dissemination of undistorted Leninism, for the unmasking of its falsifiers.”

The prosecutor: “If it was only a matter of propagating Leninism, why were you hiding in the underground? Preach within the system of party political education and its meetings.”

His response: “You know better than I that that’s impossible. The fact that Leninism has to be preached from the underground demonstrates better than anything that the current party leadership has deviated from Leninist positions and thereby lost the right to leadership of the party and has given to communist Leninists the right to struggle against that leadership.”

Ben Nathans: Bravo. This is Grigorenko who is a major general in the Soviet army. When people talk about dissidence as coming from the fringes of society, I always bring up Grigorenko because he is as embedded in that society and as much a product of its educational system as anybody you can imagine. I hope this is one of the deep themes of the book that emerges over time: orthodoxies produce their own heresies.

It’s impossible to imagine a person like Grigorenko existing in any society other than that of the Soviet Union. He is a poster child for Soviet values. These people are the products of their own system. They’re very Soviet in a way, but they’re repurposing the cognitive categories and the moral ideals in directions that the state had not anticipated.

Jordan Schneider: Ian, in a lot of the more recent protests in China as well, you have this critique from the left as much as from a small-l liberal right. The contemporary Chinese government is not living up to the ideals of socialism as defined in a different way than Xi would.

Ian Johnson: When looking at these people also in the Chinese context, similarly, it’s a mistake to think of them as just coming from the fringes. There are people firmly embedded inside the system — as they say in Chinese, tizhinei (体制内), inside the system — who are critics and who write these things. Certainly in the Mao era, but even now, these are people who often have access to more information and have a better idea of the way the system works. They become that much stronger and more effective critics.

PR with Chinese Characteristics

Ian Johnson: Something else I noticed in reading the book is that the Soviet leadership seemed more sensitive to the West than I would expect in a Chinese context. In the Chinese context, maybe in the 90s when they were trying to get into the World Trade Organization, people paid attention to what Western governments said. But the Soviet leadership seemed much more concerned about how they were perceived in Western countries. Is that accurate? How much of a role did that play in the leeway that these people got in your book?

Ben Nathans: It’s accurate, and it was an extremely significant fact — this sensitivity to Western opinion. This came home to me in a moment during my research that I didn’t include in the book, but I’ll share it with you now.

Among the many genres of documents that I drew on are transcripts of Politburo conversations. During the time when the post-Soviet Russian Federation was more open to researchers, you could get your hands on quite a few transcripts of Politburo conversations, including conversations about human rights, dissidents and Western criticism.

There’s one moment where Leonid Brezhnev is on a rant about Western coverage of Soviet policy, and he starts to cite a critical article from the The Baltimore Sun. Now, I’m a native of Baltimore. I was born there and grew up there and The Baltimore Sun’s a great newspaper. It’s probably a second or third tier newspaper in the American hierarchy of papers, clearly less important and influential than The New York Times or The Washington Post or The Miami Herald or The LA Times.

So I’m thinking, “Okay, just take a deep breath here and realize that the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, one of two superpowers in the world, is getting upset by an article that was published in The Baltimore Sun.” Has there ever been an American president who could even name a Soviet newspaper other than Pravda and Izvestia? I seriously doubt it. This brought home to me the extraordinary prickliness of Soviet leaders when it came to Western criticism.

Why is that? Why does Brezhnev even care what The Baltimore Sun is saying about him or his government? It’s a clue to the idea that the Soviet Union saw itself as coming out of the same enlightenment modernizing tradition as Western countries. It didn’t see itself as civilizationally different or superior. Marxism-Leninism and socialism was seen as civilizationally superior to capitalism. But the point is that the story they were operating within is a succession story. It’s like Christianity emerging from Judaism or any of the other religious stories of religious evolution over time.

To Soviet leaders, it really did matter what people in the West thought, not just because they were competing with Western societies and attempting to outdo them, but they saw themselves as essentially genetically emerging from those societies. Therefore it was just unacceptable to be described as inferior or having lost their way in this historical trajectory that begins with the French Revolution and the revolutions of 1848 and all the things that formed the traditions of socialism and social democracy.

Ian would know much more about this than I do, but having read a little bit in the debates about Asian particularism when it came to defending Asian countries against charges of human rights violations, and the idea that human rights are a Western cultural code, and they’re not really — the individualism that is embedded in human rights thinking is not appropriate for societies in which the family and the collective is the preeminent unit. The Soviet leaders never took that defense the way the leaders of, say, Singapore or China have been known to do. They saw themselves as having a superior set of human rights norms than that of the West. They had outdone the West at its own game.

This is a really crucial difference and remains true today, although the contrast is not as sharp because Putin and his entourage are fed up with criticism from the West that they just don’t care anymore. They no longer defend their values on a continuum that includes the West. Now the talk is of the Russian world, of Russia as a civilization unto itself. That way of thinking is much older and much more familiar to the Chinese.

Ian Johnson: The Chinese government's response to human rights criticisms is purely tactical. They might issue white papers highlighting human rights issues in the United States, for example, but this is often a way of “thumbing their nose” at the U.S., essentially saying, “You think we have problems? You've got equally big ones.” Unlike countries that signed agreements such as the Helsinki Accords, committing to specific benchmarks, China has never truly agreed to external human rights standards. Fundamentally, they don't value Western opinions on these matters as much.

This highlights significant differences between the two systems. In the Soviet Union, deep-seated economic problems fueled a groundswell of support for dissidents. In China, however, economic conditions improved relatively quickly after the Mao era, which meant less grassroots support for dissident movements. This echoes something you write in the conclusion about the German historian Mommsen’s observation about the Nazi era — “resistance without a people.”

China's success with economic reforms, something Gorbachev couldn't replicate, effectively undercut much of the potential dissident support in China compared to what existed in the Soviet Union.

Ben Nathans: Yeah, that’s super important. If you ask yourself what was the single greatest, most resonant achievement of the Soviet state across its entire history, everyone from that country will tell you the defeat of Nazism in World War II. That was the shining moment. If you listen to Putin talk, he just reinforces that point — that it’s the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War, this epic struggle that cost the Soviet Union roughly 25 million lives.

The problem with having a peak performance like that is that it’s fixed in time and it’s constantly receding in time from the current generation. The Chinese government’s greatest achievement is having lifted 700 million people out of poverty. It continues to provide a form of material well-being — it’s the gift that keeps on giving. It’s not stuck in time. It’s not an event that ended in 1945, the way the so-called Great Patriotic War ended. As a source of not just legitimacy, but prestige, the Chinese government has a product that is much more effective than the Soviet government or today’s Russian government has.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, the theme of prestige is something that has come up on past episodes of ChinaTalk. We did a four-hour two-part series on the new book, To Run the World. Ben, the sheer level of embarrassment among Soviet leaders is remarkable. You frequently mention how the Politburo would hold 30 or 40 meetings just to discuss handling someone like Sakharov. It's remarkable how worried they were about individuals making funny jokes at their expense and pointing out to the rest of the world that they’re a society where the emperor doesn’t have any clothes.

Ben Nathans: Yes, it’s something that I continue to struggle to understand. On the one hand, there was a tremendous degree of self-confidence. The Soviet Union won the war, they launched the first human into space, they were the largest country on earth, feared and respected by everyone, they were no longer alone in the socialist camp, it had a series of allies in Eastern Europe and was gaining more in Asia and in Africa, it even had Cuba in the Western Hemisphere. There were many markers of success and achievement.

This isn't even considering their performance in elite pursuits like chess, physics, math, ballet, poetry, and literature. In terms of high culture, all the benchmarks were met. Yet, as you point out, these apparent symptoms of insecurity were completely out of proportion to the actual threat. One gets the feeling there was a deep, subterranean anxiety they simply couldn't shake.

Henry Kissinger famously stated during détente that if a kiosk in Moscow could sell The New York Times or The Washington Post — effectively breaking the Soviet state's information monopoly — it wouldn't matter. It wouldn't make any difference. Evidently, the Politburo thought otherwise. They believed they couldn't afford any disruption to their control over what information Soviet citizens could access. That's why they tried to jam Western shortwave radio broadcasts, punished dissidents, and conducted thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of apartment searches in a completely quixotic attempt to literally destroy all samizdat. This was impossible because it was an entirely decentralized system of textual production; you simply can't control it, and the KGB failed miserably.