The Pacific War

How to write fantastic history with Ian Toll

For the 80th anniversary of the Allied victory over Japan, ChinaTalk interviewed Ian Toll about his Pacific War trilogy, which masterfully brings America’s bloodiest war — and the world’s only nuclear war — to life. Ian’s detailed scholarship creates a multisensory historical experience, from the metallic tang of radiation after the bombs were dropped to the stench of Pacific battlefields.

Ian’s forthcoming book, The Freshwater War, will explore the naval campaign the US fought against Britain on the Great Lakes between 1812 and 1815.

Today our conversation covers….

How Ian innovates when writing historical narratives,

Whether Allied victory was predetermined after the US entered the war,

Why the Kamikaze were born out of resource scarcity, and whether Japanese military tactics were suicidal as well,

How foreign wars temporarily stabilized Japan’s revolutionary domestic politics,

How American military leadership played the media and politics to become national heroes,

Lessons from 1945 for a potential Taiwan invasion.

Cohosting is Chris Miller, author of Chip War. Thanks to the US-Japan Foundation for sponsoring this podcast.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app.

The Pacific War — A Writer’s Guide

Jordan Schneider: I want to start with your closest scholarly forebearer, Samuel Eliot Morison. He was FDR’s buddy who ended up getting presidential approval to be embedded in the fight in the Pacific. Over the next 20 years, he published a 15-volume, 6,000-page history of United States naval operations in World War II.

For this show, aside from reading your 2,000 pages, I also read a few hundred pages of Morison, which — while there are echoes — feels like it was of a different time, era, and audience. When reflecting back on where you chose to spend your time in research and pages, compared to what he thought was most interesting and vital, what were the things that you both agreed needed the full treatment? What were things that you felt comfortable writing in the 21st century that you could spend less time on? What were some of the themes that you wanted to emphasize to a greater extent than he did in his book?

Ian Toll: Well, Morison will always be the first, if not the greatest, historian of the Pacific War. It’s an unusual case because Morison pitched the president of the United States — who was himself a former assistant secretary of the Navy — this idea. FDR ran the Navy day-to-day during the Woodrow Wilson administration and was fascinated with naval history going all the way back to the American Revolution. He was a collector and an antiquarian.

FDR was unique as a president in anticipating the importance of research and writing to document the history of this war, even before it began to unfold.

Samuel Eliot Morison, a historian at Harvard who was well-established in the field, said, “Why don’t you just put me in charge of this whole project and let the Navy know that I get an all-access pass to the Pacific War as it’s happening? I will produce a multi-volume official history — but really a history written by me, Samuel Eliot Morison, with all of my strongly opinionated views, having witnessed many of these events, in some cases from actually being aboard a ship in a task force as it went into battle.”

Morison’s concern was to write the first draft of the history, and he did a remarkable job. He had access in a way that no outsider could possibly have had. He became personal friends with many of the admirals who fought that war and was a direct witness to many events. That was true in Okinawa, where he was aboard a ship in the task force and could work his personal impressions into the narrative.

All of that is very unique. Morison was seeing the war through the eyes of his contemporaries. He was very much involved in the debates that the admirals had as they were rolling across the Pacific. He was probably less interested than I am in the way that the war was experienced by the ordinary sailor, soldier, and airmen, and more interested in grand strategy.

I like to pull those together — the way the war unfolded in the eyes of those who fought it, but then also returning to the conference rooms where the planning unfolded. I wanted to understand how the politics of inter-service rivalries in the US military affected decisions — that was an important story unique to the Pacific because of the divided command structure.

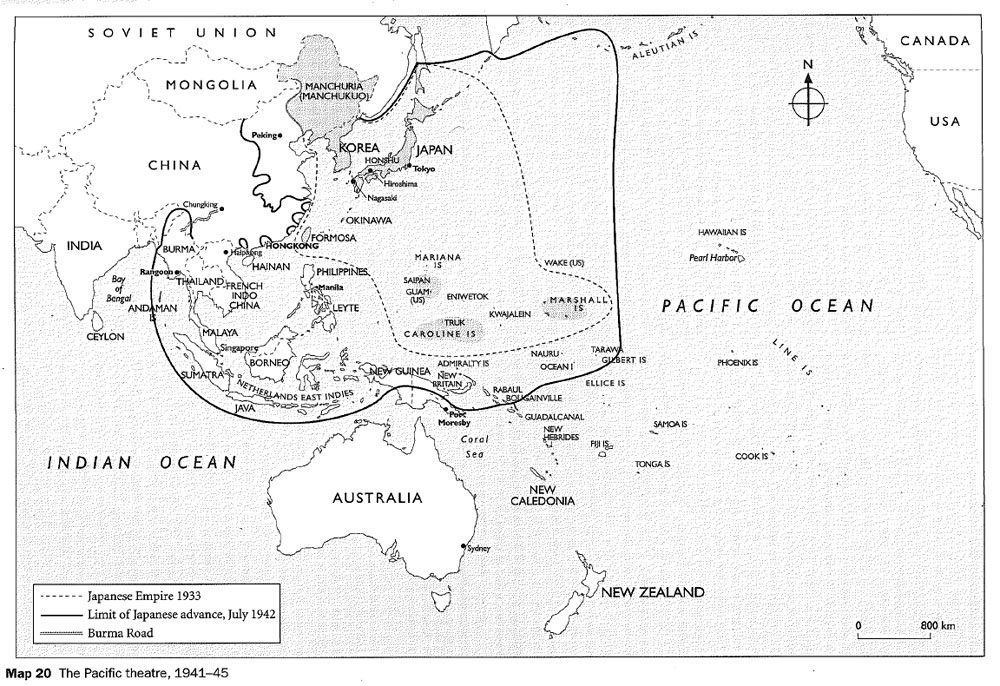

This Solomon-like choice to say the South Pacific will be MacArthur’s domain — the US Army will be in charge of the South Pacific, the Central and North Pacific will be Nimitz’s domain — meant we were really going to divide this enormous ocean into two theaters. We were going to let the Navy have one, let the Army have one. That was to establish peace within this large and fractious military.

In some ways, that was a suboptimal decision. In other ways, it seemed to work out fine because the United States had the ability to mobilize such an enormous war machine, such that we could fight two wars in the Pacific.

We fought two parallel counteroffensives — one south of the equator, one north of the equator. Because we had the ability to do that, the Japanese really were unable to concentrate their diminishing forces to meet either prong of this two-headed offensive.

Jordan Schneider: As you’re thinking about how to devote your research time and the pages that you allocate to these stories, can you reflect a little about your process of having all these simultaneous strains of the experiences of these individual soldiers, as well as these grand debates between MacArthur and Nimitz and the president about how to put all the pieces on the chessboard? What was both the research as well as synthesis process for you in this comprehensive history?

Ian Toll: My process, from when I first began doing this about 25 years ago, is to read everything. Now, with the Pacific War, you can’t literally read everything. The first book I wrote, Six Frigates, about the founding of the US Navy, I felt at times I was touching almost everything that had been written. That will never be the case with a war this big.

But to read very, very widely — histories, the original documents, the planning documents, the action reports, the memoirs, the letters, the letters of the military commanders and the lowest ranking soldier and sailor who experienced these events. Casting a wide net and spending years. before sitting down to write, going out and gathering up an enormous amount of material, and looking at the subject from every different angle.

Then there’s a middle step, which is important and often neglected by a lot of historians, which is to take all of that material and file it in a way that when you come back to the part of the narratives that you’re writing, you can immediately put your hands on that source to work it in. It is an information management issue, which requires a lot of thinking about how to do the research initially and how to organize it so you can then use it in the writing.

Eventually, it just becomes many thousands of documents organized in a certain way, a narrative that is going to unfold. The narrative is iterative in the sense that I may go down a blind alley and decide I need to throw that out. I throw hundreds of pages out. I’m doing it again with the book I’m writing now. To try to give the reader a sense that you’re shifting between different perspectives constantly — the perspective of Nimitz and his staff at Pearl Harbor planning an operation, then shifting immediately to the perspective of Marines in the Fifth Regiment who are landing on a beach and then carrying out the operation that you were just seeing how this was planned, then shifting to the Japanese perspective and shifting back to the US home front.

It’s a constantly shifting narrative, in which you’re looking at the same subjects from a different point of view, but then integrated into a narrative that unspools a little bit the way a novel would.

Chris Miller: How did you learn to do that, shifting perspective so smoothly? Because it’s easy to say, “Oh, shift from Nimitz’s room where he’s looking at the map, then shift to Iwo Jima.” But you do that in a way that few narrative histories do. Jordan and I both agreed that we’ve never read a 2,000-page history and wanted another page until we read yours. How do you learn that scene shifting? What were you looking at as examples? What were you reading that gave you a model for this type of vast, sweeping narrative history?

Jordan Schneider: To give a sense of what Ian does — one of my favorite scenes was Hirohito’s surrender speech, which covers 30 pages. First, there was a debate over whether or not to surrender in the first place. Then 10 pages of incredible palace drama — is there going to be a coup? Then, there was a coup, and it failed. Then the scene moves to NHK, and the phonograph is being placed, and the guy bows at the emperor’s photograph. Then you have these scenes all across Imperial Japan of different people responding to hearing the emperor’s voice in different ways.

The speech was in archaic Japanese, so people didn’t even know what it was saying. Some people decided, “Okay, if we’re going to surrender, then that means I need to do my final Kamikaze run.” Other people were saying, “Oh my God, thank God.”

It sounds overwhelming and kaleidoscopic, but it is actually one of the most incredible pieces of literature that I have consumed. Where does that all come from? How do you develop this skill?

Ian Toll: Well, I really appreciate the praise. It’s praise that keeps me going because this is hard work. I’ve been doing this full-time since 2002. That’s when I signed my first book contract. That’s 23 years, and I have four books to show for it. Part of the answer is that I take a lot of time. I throw a lot of work out. Probably a lot of that work is good, but it doesn’t work within the narrative pacing that I was going for. It’s a lot of following instinct.

I said in an author’s note that there’s room for innovation in this genre of historical narrative. It’s been a genre that has been trapped within certain ideas about narrative conventions — the idea that if you use the storytelling techniques of a novel or even a film, you might be compromising the scholarly purpose of the work. I don’t believe that’s true.

You can borrow from the techniques of novels or even films, in a way that may illuminate certain issues that you’re writing about, that may bring the reader closer to the way it felt for the participants to be there. I use research that I’ve accumulated over many years and have cast a very wide net to try to find material that hasn’t received as much attention as it should have in previous works.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about that filmic quality.. There are these moments of terrific awe-inspiring beauty that you point to — these ships blowing up and these massive artillery barrages, the sunrise over Mount Fuji that the admirals see as they’re pulling into the harbor, about to accept the surrender of the Japanese and the way that they see that as this flag that they’ve been fighting against and finding on people’s corpses for the past six years.

Your book made me watch some more World War II Pacific movies, and I was disappointed, honestly, with what I saw relative to the incredible Technicolor visions that you and your narrative painted in my head. How did you develop that sensibility and when did it become clear to you that you needed to make sure that your readers have some of the images that were in these soldiers’ heads in ours as well?

Ian Toll: As I’m coming through these sources, I often zero in on these images, descriptions of images. One of the things you’ll find if you start reading Pacific War narratives again and again is that you will have an American from Illinois who had never traveled beyond a few miles where he was born, seeing these extraordinary things in the Pacific, this exotic, remote part of the world.

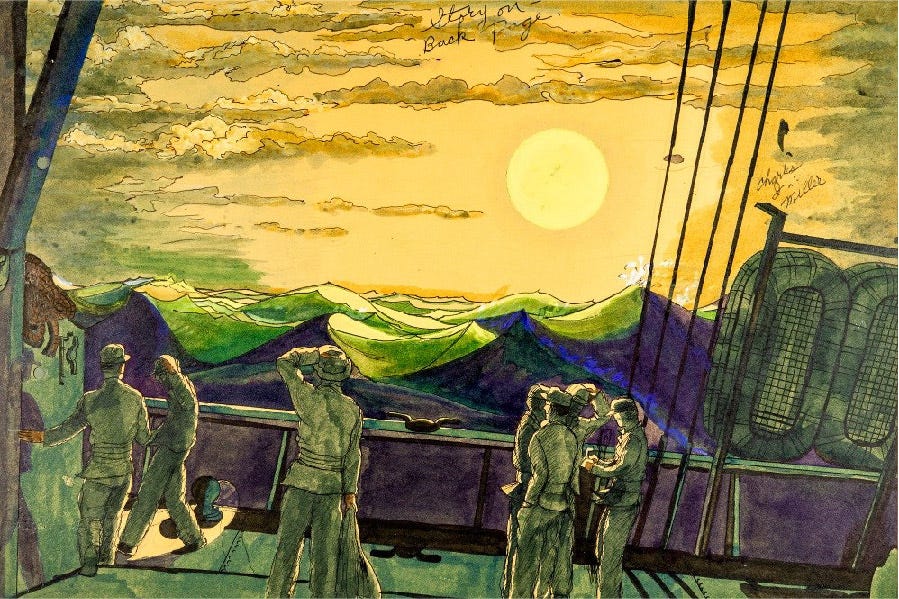

Often they’d describe the sunsets, and you’d get a sense that they are having a sublime, ineffable experience seeing these things. That grabs my attention when I see it. Then I want the reader to see that image, but then also get a sense of how that felt for people who had not traveled widely before being thrown into this extraordinary war.

On that subject, there’s a whole genre of wartime art. You have talented watercolorists working on a destroyer who took a sketchbook along and brought back images, which are particularly important because you weren’t permitted to take a camera with you in the Pacific War. You had to have special authorization to have a camera. The art sometimes is useful to see the war through the eyes of the people who were there.

Those aspects of the Pacific War narratives always jumped off the page for me. Then I tried to in turn weave them into the narratives.

Jordan Schneider: There’s beauty and there’s also horror. You spend a lot of time describing deaths. Even when people aren’t literally dying, the smell of some of these battlefields and the smell of the corpses is another thing that’s going to live with me for a while. That contrast struck me — these incredible sunsets and these spectacular displays of mechanical might and fleets that are extending farther than the eye can see. Then every once in a while, they blow up and people die horrific deaths because of what all these machines can do. How did you try to do justice to that as well?

Ian Toll: In the case of the Pacific War or any other war, really any other aspect of World War II, there’s plenty of carnage in the historical record. These things happened. The challenge becomes describing those in a way that gives the reader a sense of what it was like to be there. You’re right about the smell — that’s another thing that just jumps off the page. If someone describes a smell, whether it’s the awful smells that you get on a battlefield or even the smell of flowers on a beach, those tend to leap out at me, and then I try to find a way to work those in.

We have five senses. If you can get three out of four of the physical senses into a description of a battle scene, you’re able to reach the reader through more than one route. Those images, those impressions, tend to build on themselves. If you can get many of them into a narrative — not doing what a novelist does where you make it up, you need to pull these details from first-hand accounts that are reliable — but if you get many of them, that tends to build to where the reader gets a sense of what it was like to be there.

Jordan Schneider: This is my big note for the Chip Wars revised edition. Chris, we need more smell in it.

Chris Miller: You know, the place that really stood out for me in the book was on Iwo Jima, which everyone knows is this absolute bloodbath. But the discussion of the sulfuric volcanic ash all around in these subterranean caves — you got smells and also tastes, talking about the water being sulfuric in its taste. It felt like I was walking into Mordor, but it wasn’t made up in Tolkien’s mind. It was a hellhole on Earth.

Jordan Schneider: The smell and the taste that’s going to live with me forever is the Enola Gay dropping the bomb and the pilots tasting metal because of the radiation. They hadn’t looked back, but they knew that the bomb had gone off because they felt it in their molars. What more can you ask for from a historian?

Ian Toll: That detail really grabbed my attention too. That’s in one of the pilot accounts, I believe. You had this electric taste in your mouth from the explosion, from the bomb. They noticed that at the Trinity test, the first atomic bomb test in New Mexico, as well.

Chris Miller: You have these juxtapositions of extraordinary heroism and extraordinary barbarism on both sides. A lot of military histories tend in one direction or the other and don’t balance out both. You show them both being constantly present in different ways, competing impulses. Can you walk us through the ethics of what you’re recounting and how you, as a historian, try to properly balance these two competing impulses?

Ian Toll: You mean the impulses to acknowledge the humanity and suffering of the enemy — it’s part of what makes good war histories memorable, is that you have a situation in which it’s impossible for people on the battlefield not to feel a sense of hatred toward the enemy. This is murder on a mass organized scale. Then you have a war like the Pacific War, where, in some ways, that hatred reached a pitch that we haven’t seen, at least in any other American war — this dehumanization and hatred that was felt. Much of it was justified, honestly.

To evoke that for the reader, that sense of hatred, that sense that many Americans had that the Japanese were somehow less than fully human and that this justified wiping out their cities — to feel that in a visceral way for the reader because of the way you’ve shown how the war was experienced by the Americans who experienced it, by the POWs, by the civilians who were caught in the war zone in the way of rampaging Japanese armies. But then at the same time to acknowledge, to fully understand the humanity of the Japanese and the suffering of the Japanese.

It comes down to weaving these different perspectives together into one integrated narrative. Many others have done it well — such as John Toland’s book, The Rising Sun, which I recommend. He was one of the first to write the history of that war from the Japanese perspective in a way that was broadly sympathetic to the Japanese people and their suffering, while acknowledging that the Japanese militarists had tyrannized and abused that country and eventually brought on the immense suffering of 1944 and 1945.

The Kamikaze — A Problem of Scale

Jordan Schneider: The kamikaze dynamics that we get into in 1944 and 1945 are some of the most artful sections. The training system for Japanese airmen was incredibly selective, where a thousand people joined and only a hundred made it out the other side.

That led to this very elite core of fighter pilots, but ultimately, they were short of decent pilots such that pilots were so useless by 1942 and 1943 that the most efficient tactical maneuver to spend the least steel to deal the most damage on American ships was to use pilots as the 1940s version of guided homing missiles. It’s much easier to teach someone to fly into a plane than it is to dogfight with a Zero.

On one hand, it makes sense. On the other hand, you’re sending people to their deaths. On a lot of these missions, which aren’t literally suicide missions, you have Americans who are at some level doing the same thing, with flights that go off carriers where 12 planes go out and one or two make it back. But there is something that is particularly resonant and horrific about Kamikaze flights. My guess is, 500 years from now, if people are talking about anything when it comes to the Pacific War, the Kamikaze flights are going to be one of the three lines that people still remember.

How did you approach that? What are the different aspects of the story that you wanted to hit as you were describing the different parts of the Kamikaze story?

Ian Toll: The Japanese had trained what may have been pound for pound the best cadre of carrier pilots in the world at the beginning of the war. They were superb. There had been a national selection process, extremely difficult — tougher than getting into Stanford today — for getting accepted to naval pilot training in 1939-1940. Then they went through this extremely rigorous pilot training process that built these superb pilots. But they never thought seriously in Japan about the problem of expanding that training pipeline to produce many more pilots in order to fight a war on the scale of the Pacific War.

When their first team of pilots was killed off in 1942-43, with few left by 1944, they did not have a next generation of pilots to come in and carry on the fight. The decision to deploy Kamikazes on a mass scale was tactically correct in a sense. If you have pilots who you cannot afford to train — you don’t have the time, the fuel, the resources to train pilots to effectively attack ships using conventional dive bombing attacks, conventional aerial torpedo attacks, the kinds of attacks that the Japanese had used effectively in the early part of the war — then maybe what you do is train the pilot to fly a plane with a bomb attached to it into a ship like a guided missile. Maybe that’s simply the best tactical use of the resource that you have.

That is ultimately what persuaded the Japanese to go ahead and deploy Kamikazes on basically their entire air war — their entire air war was a Kamikaze war in the last year of the war. Then you have, on top of that, this question of the morality of sending 20-, 21-, 22-year-old men to their certain deaths in this situation.

The part of the story that has been neglected and forgotten in the West is that this was immensely controversial, even in Japan. The Kamikazes came to be revered. But at the outset, even within the military, within the Navy — the Navy was mainly the Kamikaze service that launched the Kamikazes — there was immense opposition to this within the ranks of the Japanese Navy. It took time for this to be accepted, but this was the way they were going to fight this war.

Trying to understand what it was like to be a Kamikaze pilot, to draw upon these letters and diaries that have been published, many of them in English, but then also what it did to the crew of a US ship to know that they were under this kind of attack. The unique sense of horror that they felt operating off of Okinawa in particular — the height of the Kamikaze campaign — where 34 ships were sunk, and many more were badly damaged with US Navy casualties running well into the thousands. Certainly, more Navy personnel were killed than Army or Marines at the Battle of Okinawa, as bad as the ground fighting was. That unique sense of horror and loathing that they felt as these planes came in making beelines, flying suicide runs, and doing terrible damage.

Chris Miller: I was struck by the other facet of how the Kamikazes emerged. There’s the logic of how you most efficiently use your limited number of airplanes and pilots to sink ships. But it also seemed like the Japanese army and all of its island defenses were pursuing a Kamikaze strategy. In all these island campaigns, 90% plus of the Japanese garrisons were killed. They would start the battle knowing they would lose, but trying to exact as much punishment as they could, which at a strategic level is rational, but tactically a brutal way to fight a campaign.

I found myself wondering, did the Japanese army have its own version of the Kamikaze mentality? Was the entire war effort on Japan’s side suicidal after 1942? It was obvious to everyone that the production differences were large enough that Japan would definitely lose. Is there something to that analysis?

Ian Toll: Absolutely. You could say that Kamikazes are a metaphor for the entire project of Imperial Japan, particularly after Midway and Guadalcanal when we reached the second half of the Pacific War, when it was clear that Japan was going to lose the war. Whatever that meant — losing could be many different versions of losing the war. But historians have traced a cultural change that occurred in the Japanese military after the Russo-Japanese War and then after the First World War, in which the Japanese Army leadership convinced itself, “We have got to do something about this problem of our soldiers surrendering. That’s not acceptable.”

They actually altered the military manuals and the standing orders to say, “You shall not surrender in any circumstance. There will never be any surrender in the Japanese Army.” That was a very fateful decision because once you’ve put your soldiers in that situation, which they know they’re not going to survive, that they’re going to fight to the last man, that alters the psychology on the battlefield and leads inevitably to a much more brutal environment.

On one island after another, starting most famously on the Aleutian island of Attu in the spring of 1943, you had entire Japanese garrisons fighting and dying to the last man. This being celebrated in Japan by a press that was being very closely guided and censored by the regime, building in Japan a sense that this is an extraordinary act of bravery, of commitment, of fanaticism that the allies, the Americans, would never be able to match.

This was going to be the secret weapon for the Japanese, showing that they were willing to make much greater sacrifices than their enemies were.

As the war went on and US forces drew closer to Japan, the story changed to, “This is how we’re going to protect the homeland. We’re going to show the Americans that the cost of invading our homeland, of trying to occupy our homeland, is so great that they won't want to pay it.” It became a question of whether they could force the Americans to the negotiating table to resolve this conflict in a way in which Japan would have to acknowledge its defeat. That would mean giving up some portion of its overseas empire, but preserving its emperor system and keeping American and allied troops out of Japanese territory. That became a driving obsession of the Japanese leadership in the last year and a half of the war.

These fanatical demonstrations, fighting to the last man on one island after another, the Kamikazes, all became a kind of theater. A way of showing the Americans, “This is what you’re dealing with. We’re different from other people. We’re willing to die — the whole country will die to the last man, woman, and child if necessary.” Wouldn’t it be better to sit down and negotiate some solution to this war, which leaves us with some vestige of the Imperial project intact?

Inside Japan’s Imperial Project

Jordan Schneider: There’s of course the irony that by the time the Americans land, MacArthur says, “Actually, when we got here, we were taking a big bet that they wouldn’t want to fight anymore.” Somehow, someone snapped a finger and the rebellion turned off, or we would be in trouble. We didn’t have enough troops to do this. But the fact was, once the war was done, the war was done. The only people still fighting were five guys in the hills of the Philippines who just didn’t get the message or something.

Another contrast is why Nazi Germany took it to the end and why the Japanese took it to the end. With Nazi Germany, it was one guy and all the generals. Definitely by late 1944, you had a whole plot. Everyone saw the writing on the wall, and there was a wide consensus — enough to have a whole conspiracy. You had these back-channel feelers to the English. But because of the lack of a focal point and because you had a consensus, even though you had dissenting voices, they weren’t able to mobilize even as much as the Operation Valkyrie folks were.

You have this thesis in Japan of, “If we just show them how crazy we are, then they’ll come to the negotiating table.” But they never really tried to do the negotiating in the first place, aside from this conversation with the Soviets, which anyone really could have seen wasn’t actually going anywhere.

Let’s talk about elite Japanese politics as well, starting in the second half of the war. Even though everyone was doing these suicide missions, even though everyone knew they were on this national suicide mission by 1943, a few million more people had to die before we got to the inevitable conclusion. Why is that?

Ian Toll: To understand what was happening in Japan’s ruling circle in the last year of the war, it’s necessary to go back to the beginning of the 1930s and understand how Japan descended into militarist tyranny. The story is one of extraordinary turmoil, chaos, revolutionary energy, assassinations, uprisings, and almost a complete breakdown of discipline within the ranks of the army, but also the Navy.

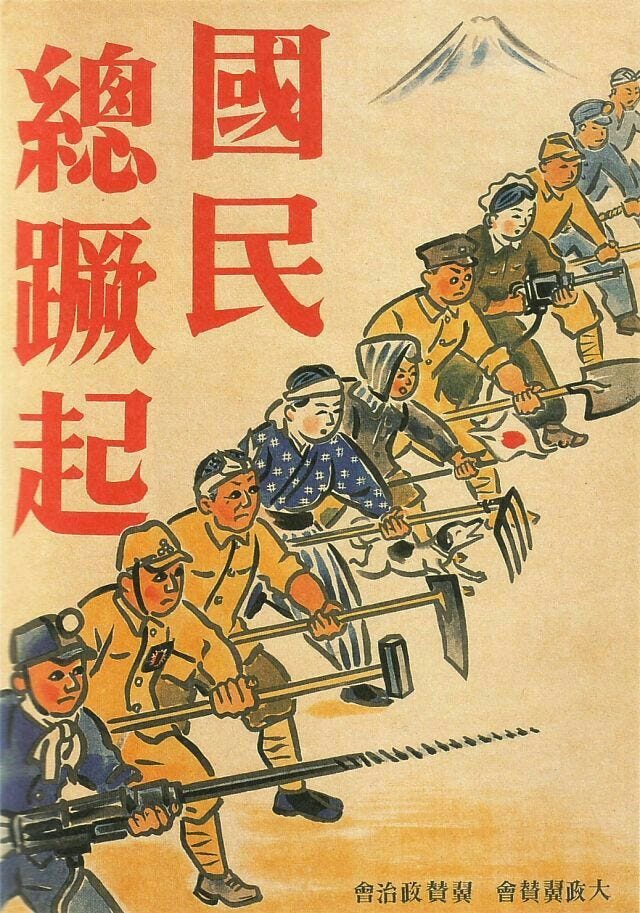

Again and again, hot-headed extremist officers and factions of younger mid-ranking officers threatened the Japanese leadership at gunpoint, forcing a much more right-wing, fanatical, imperialist, and aggressive foreign and domestic policy. Increasingly, the generals and admirals were running every aspect of military, foreign, and domestic affairs. The army took over the Japanese education system in the 1930s.

What happened with the China incident — the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 — and then the attack on Pearl Harbor and the war with Great Britain and the US beginning in 1941, was that these large foreign wars tended to heal, or at least stabilize, this domestic turmoil within Japan.

The leadership saw war as a way to maintain a fragile peace and stability within a society that was in many ways very revolutionary.

As you approach the end of the Pacific War, the problem isn’t whether to surrender or not. The problem is that whatever Japan did as a country — if they surrendered, if they initiated negotiations, if they tried to use diplomacy to get out of this war — there was the threat of a resumption of these assassinations, a civil war. You could have a civil war between different elements within the Army. You could have fighting between the Army and the Navy. This was seen in Japan as a real danger.

To complicate the picture even more, in the US we had a window — imperfect, but we had a window — into what was happening within the ruling circle in Japan because we were reading their diplomatic mail. We had broken their codes, communications between the foreign ministry in Tokyo and Japanese embassies throughout the world. We were intercepting those messages, decoding them, and reading them.

We were aware that the Japanese, by the spring of 1945, had seen their last hope as bringing Stalin and the Soviet government in to mediate between the US and Great Britain. The Japanese had a historical precedent for this. The end of the Russo-Japanese War ended with a negotiated peace between Russia and Japan, which had been mediated by the US. Theodore Roosevelt won a Nobel Prize for Peace for that mediation.

They were trying to replicate what they had seen as the acceptable end to the Russo-Japanese War — a negotiated settlement which allowed them to maintain and build their empire. Here, they would like to try to negotiate a truce. They were deeply divided within the ruling circle over what such a negotiated arrangement might look like. But the point often forgotten in the West is that it wasn’t just a division — it was a fear of a descent into complete chaos and civil war, which would make it impossible for the Japanese government to do anything in an organized way.

Our leaders understood enough of that dynamic that we saw the necessity of strengthening the peace faction within the ruling circle, and neutralizing the Army in particular, which wanted to fight on. The atomic bomb became a means to that end.

Chris Miller: But the violence of Japanese politics in the ’20s and ’30s ends up seeming like a really important driver of the violence of Japan’s war effort and even the suicide dynamics that we just discussed. You get some of that in Japanese army politics in the ’20s and ’30s as well. It’s almost as if the Japanese army took over the entire country not just in terms of running the schools, but in terms of running the culture to a substantial degree.

Jordan Schneider: Yamamoto famously was doing his best to talk everyone out of bombing Pearl Harbor. But then at a certain point, he says, “All right, you guys are dumb enough to do it. Might as well do the dumb thing the smart way.”

The thing that strikes me about the tension of this narrative history is that once you get to Pearl Harbor and the American political reaction to it, that is your turning point — America’s decision to fight this war in the first place. Regardless of whether Midway had gone this or that way, if the Marines had gotten kicked off of Guadalcanal, you have such an enormous material imbalance between the Americans and the Japanese.

If, because of Japanese politics, you’re taking off the table Japan ever wanting to cash in their chips and negotiate, then it seems like a US victory was inevitable. What do you think about that inevitability question? If it’s all inevitable, aside from the human drama of the smells and the visuals, what is the point of spending so much time and energy studying the Pacific War?

Ian Toll: It’s an issue that will never be resolved. It’s the question of whether we want to take a determinist approach to understanding WWII. I probably lean a bit more toward the determinist way of thinking about it.

Winston Churchill, in his post-war memoir of WWII, had a famous passage in which, as soon as he had heard the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he said, “So we had won after all.” Meaning that this entire conflict, including the conflict with Nazi Germany, was now going to be settled. It was just a question of the proper application of military power. Now, that was written many years later. I think it was deliberately provocative in that mischievous, Churchillian way. But I do think it is true that before the attack on Pearl Harbor, you had a deeply divided political situation in Washington in which the isolationist movement was perhaps gaining strength in the fall of 1941.

This is a movement that had strength in both the Democratic and Republican parties. It had strength in every region. It was a formidable force in our politics, a sense of real moral fervor around the idea that we were not going to be dragged into a global war. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, that movement collapsed overnight. When I say overnight, I mean literally overnight. FDR asked for a declaration of war against Japan the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It passed both houses of Congress. I think there was one dissenting vote in the house. There was a unanimous vote in the Senate.

It does not go too far to say that this one decision the Japanese made to attack and launch a surprise attack at Pearl Harbor completely altered the domestic politics around going to war against Japan. Three days later, Hitler made the curious decision to declare war on the United States when we hadn’t declared war on him.

Then it was a global war, and the largest economy in the world — the economy with the greatest latent military power — was a combatant.

Not only were we combatant, but we had the broad public political consensus that we needed to quickly mobilize our economies for war, which we did. I think that was the turning point. It was the attack on Pearl Harbor and the reaction — the political reaction within the US — that really made it inevitable that not just Japan, but Nazi Germany would be finished within three to four years.

The one other major contingency is that the Soviets were able to stop the German attack on the Eastern Front and stabilize that war and survive long enough so that Allied supplies could get in, allowing them to turn the tide. If there had been some surrender on the Eastern Front, that could have taken the entire war, including the Pacific War, in a different direction.

“What Becomes of a General?”

Jordan Schneider: Let's talk about the generals and admirals, starting with Chester Nimitz…

Paid subscribers get early access to the rest of the conversation, where we discuss…

The various command styles that shaped US military strategy in the Pacific,

How General MacArthur and Admiral Halsey became media darlings —controlling public opinion and war politics in the process,

The evolution of submarine warfare and Japanese defensive strategy,

Counterfactuals, including a world where the Allies invaded Taiwan,

Broader lessons for the future of warfare, especially in the Taiwan Strait.