Third Plenum Industrial Policy: US-China Mirror Imaging

The Emperor's New Clothes Are Just Vintage

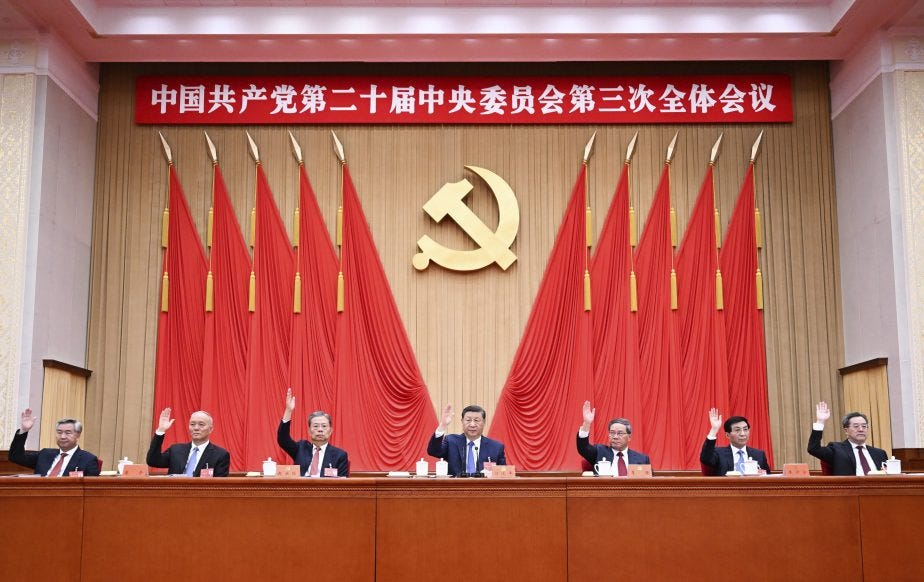

Kyle Chan is an American postdoctoral researcher in the Sociology Department at Princeton University and the author of the excellent High Capacity substack. Kyle’s guest post unpacks the industrial policy implications of China’s Third Plenum resolution. The Third Plenum is a high-level meeting of the CCP Central Committee, during which the Party’s decision-makers announce their vision for the national economy.

Between an assassination attempt and a last-minute candidate swap, betting markets are having a field day with US political uncertainty. Chinese politics, by contrast, appears quite stable. The latest Third Plenum resolution — a crystalized overview of China’s all-out effort to dominate the industries of the future — represents a doubling-down in the Sino-American industrial policy showdown.

From economic complements to competitors

The US and China used to be economic complements—or so the story goes. China did low-wage manufacturing while the US focused on higher-value services. American companies would come up with products, make them in Chinese factories, and then sell them around the world. “Designed in California, assembled in China” originally seemed like a win-win relationship.

Now, the US and China increasingly see each other as direct economic competitors, fighting for slices of the same pie. This is partly because China has moved up the value chain, challenging the US, Europe, and Japan in high-tech industries from electric vehicles to machine tools.

But this is also partly because the US has decided—or realized, depending on how you see it—that letting China take over manufacturing is no longer acceptable. Production of furniture, toys, and clothing will never come back. But for industries like semiconductors and solar cells, the US has started to put up a fight.

Both the US and China are reaching deep into their economic toolkits to outcompete each other. They are dusting off old tools, like tariffs and large-scale government funding programs, as well as coming up with new ones, such as China’s government guidance funds and the China Chips Guardrails. They are using diplomatic and foreign policy measures to shape global supply chains in their favor, with the line between economic policy and national security now more blurred than ever.

The Third Plenum: dominate the industries of the future

The industries of the future addressed by the Third Plenum resolution include information technology, AI, aviation and aerospace, new energy, new materials, biomedicine, and quantum technology. “Made in China 2025” was just the beginning.

I suggest treating the Third Plenum resolution (along with most CCP documents) like a burger and looking for the meat in the middle. There, you’ll find the section on “high-quality development” (高质量发展) and “new productive forces” (新质生产力). These two concepts, taken together, are part of a broader shift in China’s development strategy from catch-up economic growth to pushing out the technological and industrial frontier. (Arthur Kroeber has a great analysis of “new quality productive forces.”)

“High-quality development” focuses on the “hard economy.” This includes building up advanced manufacturing, industrial upgrading, and shoring up supply chains. It also includes infrastructure from railways to the new “low-altitude economy” of drone delivery systems. Digital technology is featured prominently but almost always in the context of enhancing or supporting the so-called “real economy” (实体经济). This lines up with China’s lukewarm attitude towards generative AI, which the resolution only mentions briefly in the context of cyberspace governance (as Kevin Xu has pointed out).

“New productive forces” focuses on science and technology. China doesn’t just want steady improvement but also “revolutionary breakthroughs in technology” (技术革命性突破). These breakthroughs are supposed to give rise to new industries that will become new drivers of economic growth going forward.

[Jordan: this line of thinking has Soviet origins! See Brezhnev and his bet on the scientific-technical revolution as the deus-ex-machina that he hoped would save him from having to do deeper structural reforms to the economy. Excerpt below from Yakov Feygin’s excellent new book Building a Ruin.]

To achieve this, China wants to build up its “comprehensive innovation system” (全面创新体制机制), providing stronger incentives and more flexibility to individual researchers and research organizations. At the pinnacle of this system are China’s top research institutions and universities as well as its “leading high-tech enterprises” (科技领军企业) — think Huawei, CATL, and BYD. The cultivation of human talent (人才), both homegrown and foreign, is also a key pillar in this strategy, which fosters not just top researchers in science and engineering but also a “first-rate industrial technical workforce” (一流产业技术工人队伍) to build and operate the high-tech factories of the future.

A Warped Hall of Mirrors

As I read the Third Plenum resolution, I couldn’t help but tick off the commonalities with Jake Sullivan’s speech on US industrial policy: strategic industries, supply chain resilience, innovation, long-term investments, infrastructure, clean energy. Analyzing American and Chinese economic policy these days feels like looking down a hall of warped mirrors. China and the US have clearly drawn policy inspiration from each other.

China wants to replicate the venture capital ecosystem of Silicon Valley. Efforts to loosen up research institutions and give individual researchers a greater share of the fruits of their innovations are clearly inspired by the American academia-to-commercialization pipeline.

The US, for its part, has become much more open to large-scale state intervention in critical sectors of the economy, like the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act. US efforts to leverage access to its large market to compel foreign firms to invest domestically is a classic Chinese tactic (as I’ve written about). American policymakers have a renewed interest in the “hard economy,” often drawing comparisons with Chinese manufacturing and infrastructure.

The Persistence Gap

One major difference between American and Chinese industrial policy is what I call the persistence gap. The Third Plenum resolution lays out the next phase of an industrial strategy that China has been pursuing for years — if not decades. China’s persistence in areas like electric vehicles, lithium batteries, and even aircraft manufacturing seems to be paying off.

The US, on the other hand, faces the risk of sharp pivots in its industrial policy. The sizable progress made in bringing in foreign investment and building up American manufacturing through the IRA and CHIPS Act could be in jeopardy if a new administration decides to abandon these programs. This policy uncertainty and instability creates a “policy discount factor” that undercuts the crowding-in effect of industrial policy when it comes to attracting long-term private investment.

The Elephant in the Room

China and the US are the elephants in each other’s policy rooms. Parts of US industrial policy is a response to China’s industrial policy and economic statecraft in areas like legacy semiconductors and critical minerals. China’s industrial policy in turn is driven partly by a desire to reduce its economic vulnerability to the US and its network of allies and partners, such as US-led export controls on GPUs and lithography equipment. Both countries are trying to de-risk from each other.

While the US has been vocal about China, China’s focus on the US has been quieter but arguably deeper. Xi Jinping’s explanation of the Third Plenum resolution uses stronger language than the resolution itself. Xi cites “intensifying international competition” (日趋激烈的国际竞争) and states that “external efforts to suppress and contain China are continuously escalating” (来自外部的打压遏制不断升级). Later, Xi is harsh in his assessment of China’s lack of progress in countering these threats, stating that “the ability of others to control key and core technologies has not fundamentally changed” (关键核心技术受制于人状况没有根本改变). The US is the silent backdrop to so many of China’s policy efforts.

As this economic contest heats up, it’s worth appreciating the irony of how China and the US keep defying each other’s ideological beliefs and expectations. Washington is annoyed that an authoritarian single-party system like China can innovate and produce global industrial leaders. Beijing is annoyed that a messy democracy like the US keeps churning out world-changing technology and industrial policy to boot.