What Drives China's Foreign Ministry Today? Drinking with Xi, foreign ministry fan clubs, and modern diplomacy in the age of the Wolf Warriors

The wolf is the wolf, not the lamb. BTW, China is not a lamb

The Foreign Ministry is currently under serious pressure, trying to manage its messaging on the Russian invasion of Ukraine while keeping its distance from events - but it may not be able to continue like this for long.

With reports suggesting that some Foreign Ministry officials even asked FT journalists whether the invasion was really happening or merely fake news, as discussed by Adam Tooze in a recent show, how the Chinese government chooses to address this crisis may impact their international standing for decades to come.

Can China be a player on the world stage without choosing sides? Will attitudes towards Russia have a knock-on effect on attitudes towards China? Does its reluctance to condemn Russia undermine its supposed belief in the territorial integrity of sovereign nations? And even if it gets the top level policy right, is today’s Foreign Ministry up for the challenge of execution?

Late last year I had a chat with author Peter Martin (@PeterMartin_PCM) discussing his new book China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy. In the first half of our conversation, which I encourage you to check out here, we go into the historical origins of Wolf Warrior diplomacy. In the transcript below, we turn to the contemporary players and trends in its diplomatic scene today.

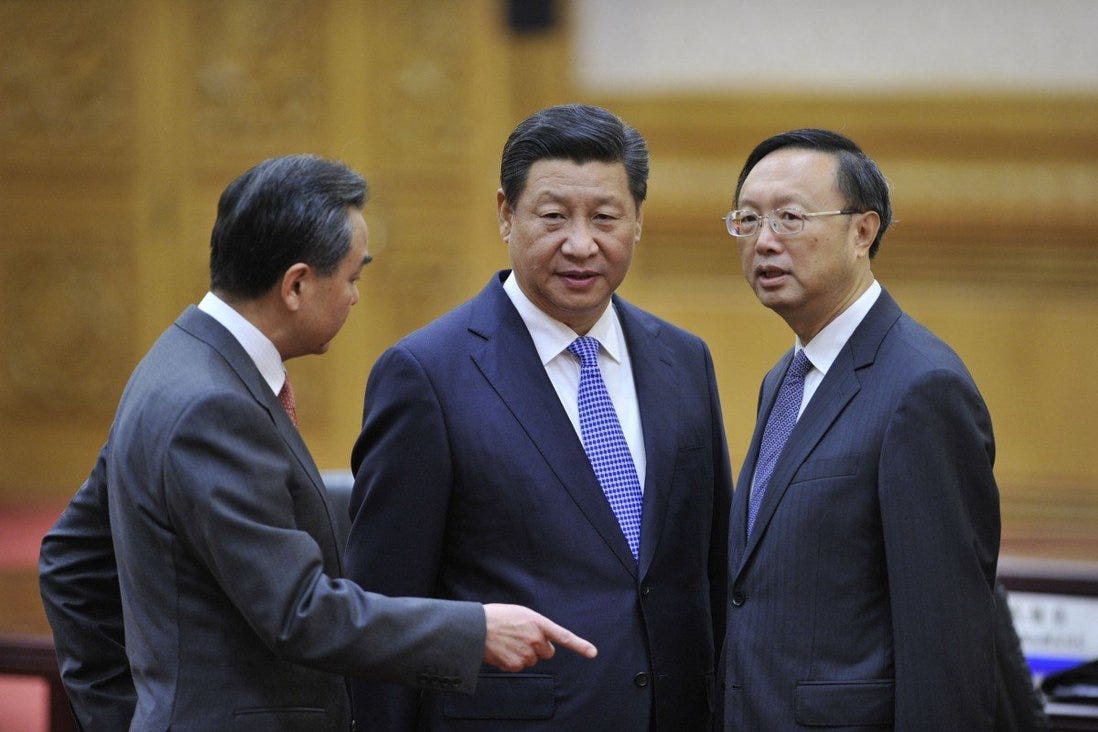

From whether Wang Yi and Yang Jiechi are friends with Xi Jinping to how the Foreign Ministry has been forced to play catch-up in overt displays of nationalism, a new generation of Chinese diplomats who have only ever known China as a strong power is entering onto the world stage. Understanding this new context will be critical for analysts and policymakers hoping to parse what they see out of the Foreign Ministry.

Also returning as co-host is Schwarzman scholar Jason Zhou (@DukeOfZhou).

Transcription and editing by Callan Quinn. This episode was recorded pre-Ukraine invasion.

Which officials drink the most Maotai?

Jordan Schneider: Going down our list of our favorite modern Chinese Foreign Ministry officials: Wang Yi. How did he get to the position he's in today? What's it like taking a plane ride with him and some other Politburo members flying off to Geneva or Washington DC?

Peter Martin: Unfortunately he doesn't take any foreign press with him on overseas trips so I can only speculate from great distance.

I heard this anecdote about Xi and Wang drinking Maotai together on the plane, which I think is is probably true. By all accounts, Xi Jinping has enjoyed Maotai on many occasions.

Jordan Schneider: But apparently he doesn't like Desmond Shum enough to drink [with him]. It was detailed Red Roulette that Xi wouldn't drink around him.

I love someone telling you that not only did they [Xi and Wang] drink a lot together, but they would drink more than the other officials.

I wonder if there's a thing going on where all the other officials after two shots feel they have to be like “oh I can't do it anymore” just to make Xi look good, or if these guys are actually really killing themselves and stepping up to the alcoholic plate.

Peter Martin: My impression is that Xi Jinping can really take his liquor but [I don’t know about Wang Yi].

I enjoy putting ChinaTalk together. I hope you find it interesting and am delighted that it goes out free to eight thousand readers.

But, assembling all this material takes a lot of work, and I pay my contributors and editor. Right now, less than 1% of its readers support ChinaTalk financially.

If you appreciate the content, please consider signing up for a paying subscription. You will be supporting the mission of bringing forward analysis driven by Chinese-language sources and elevating the next generation of analysts, all the while earning some priceless karma and access to an ad-free feed!

Wang and Yang’s replacements

Jason Zhou: Earlier this year, Kurt Campbell, who's the top US official in the Asia Indo-Pacific area, said that Wang Yi and Yang Jiechi are not within 100 miles of Xi Jinping’s inner circle.

I'm curious to what extent you agree with that statement, especially given some of the the research and anecdotes you've related about Wang and Xi? How close do you actually think they are? And if they aren't that close, where do you think Xi is getting his foreign policy from and who are the closer confidants?

Peter Martin: Kurt Campbell in a subsequent event semi-retracted that statement. I think it's a little bit off, but it's accurate in the sense that both of them are career Chinese diplomats and are never going to have the same standing inside the system as someone who has come up on a purely political track inside the communist party.

Neither of them are really elite political players in the sense that they're not particularly involved in making deals over who gets to govern what province or what happens to the Chinese economy. They are both very much in the diplomatic lane, and I suspect they will stay there.

In that sense, it's true that they're not especially close to the inner circle. I think the place where it's probably off is that both of them, as far as I understand, do have Xi Jinping's ear on foreign policy issues.

I've heard accounts of other officials being ushered out of the room when Xi wants to have a one-on-one with a foreign counterpart and Yang being asked to stay behind to advise Xi and listen in on the details of those conversations.

That to me does suggest that Xi recognizes his value, at least as an advisor and someone who understands the outside world.

The simple fact that he was promoted to the Politburo shows that Xi Jinping thinks that foreign policy is important and that it's very important to have a US expert at that very high level.

I think the same thing when it comes to Wang Yi on diplomacy in general but especially on Asia and Japan, where his primary expertise lies.

So they have this dysfunctional role. It's very important and does involve some real closeness to Xi, but they're not sitting down in the intersections of elite politics.

Jason Zhou: Both Wang Yi and Yang Jiechi are nearing 10 years in their current positions, Wang Yi as foreign minister and Yang Jiechi as director of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission. It seems Yang Jiechi will probably have to retire given his age. Do you have any thoughts on who is likely to succeed them?

Do you think Hua [Chunying, assistant minister of foreign affairs] will just pick up Yang's current role? Any thoughts on possible changes in foreign minister leadership going into the 20th Party Congress?

Peter Martin: Obviously I have no idea what's going to happen, but that shouldn't stop me trying to answer the question.

One person who's spoken about a lot is Le Yucheng, who is one of the vice foreign ministers and has shown up in a variety of settings that suggest he might be poised to take over from Wang as foreign minister at some point.

Five years ago, there was a lot of speculation that Song Tao from the International Liaison Department was going to replace Wang Yi. That didn't happen so you never want to trust the Beijing rumor mill too much, but I think there's a lot of focus on Le as someone who might take over.

You can see it just from his being teed up for a lot of high-profile media appearances at home and abroad, and he's making very wide-ranging speeches on Chinese foreign policy.

So there does seem to be this indication that he's being prepared for some high-level role. Perhaps he will be foreign minister, perhaps it's something else.

“They have to listen to us”

Jason Zhou: Do you think that we're going to see larger changes in the culture at the Foreign Ministry given that we're moving away from the generation that experienced the hardships of the Cultural Revolution to a generation that came of age a bit later on during the Reform and Opening periods? Will that affect anything or do you think that they will still have to stay close to the party line?

Peter Martin: I think that one of the really striking things about the Foreign Ministry is the consistency in its culture from 1949 all the way through to today, which is incredible when you think about the changes that China has gone through during that time.

The idea that this one institution could maintain such a similar approach in the way that it conducts itself - I think the reason for that is the civilian army model is very well suited to conduct a diplomacy system with the peculiar expectations and limitations that the Chinese communist party places on the conduct of foreign policy.

I don't really expect that to change. I think it's very well suited to China. It held up during the period of international communism and it held up during the Reform and Opening era.

One of the things that Wang Yi had to deal with when he became foreign minister was this new role that China was taking on in the wake of the global financial crisis and this new leader, Xi Jinping, who had these startling new ambitions for China in the world.

In his internal speeches, Wang went back again and again to this theme of working like the People's Liberation Army in civilian clothing. Because it's been so successful and so useful in so many periods, I don't really see that aspect of it changing. But I think maybe some of the cultural assumptions of Chinese diplomats will change along the way and I guess we've already started to see that.

But we will now increasingly have generations of Chinese diplomats who have only ever known China as a strong power.

They have only ever known the Reform and Opening and the Xi Jinping era. They haven't seen China at its weakest, haven't seen the dangers of the Cultural Revolution and only know about them second hand. You've got to think on some level that will have an impact.

I remember talking to a young diplomat in Beijing and asking him whether it felt good to come from a country that's becoming more and more powerful. And he said: “oh it feels great. When I first started here we always felt like other countries didn't respect China and you could feel that they looked down on you. But now when we walk into the room, you can feel the mood change and they know that we're a powerful country and they have to listen to us.”

So I would think that those kinds of experiences would just amplify this existing trend towards assertiveness and confidence on the part of Chinese officials, but we'll have to see.

China is neither a wolf nor a lamb

Jordan Schneider: Another new dynamic over the past 30 years is social media and the ability of the Chinese state to drive the discussion, at least on foreign policy.

You didn't have revolts from below due to people being angry about certain foreign policy moves, but now, particularly from the right, you have these anecdotes of people sending the Foreign Ministry calcium because they think they need more backbone to stand up to folks.

And I think even more apparent in the domestic regulatory context - in the tech sector in particular - is you're seeing once something goes viral that the government is almost taking a reactive stance and trying to catch up.

What's your take on the dynamic between internet nationalism and the embodied Wolf Warrior diplomacy we've seen over the past few years?

Peter Martin: I think that this is a pretty mutually reinforcing dynamic between the two. In the 1990s and the 2000s there was this feeling, but public opinion got out ahead of the Foreign Ministry.

It was much more nationalistic, had much higher expectations for the role that China was going to play in the world. Chinese diplomats were scrambling to keep up and they didn't want to match the tone that many internet users used because they knew it would be damaging for China's international reputation.

And at that time they had cover from the Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao leaderships, which on the whole, at least until 2008-09, wanted to cultivate a popular image in the world and improve China’s reputation. But that's changed recently.

We've seen this melding of popular nationalist discourse and the way that the government expresses itself.

Ten years ago, if you read an editorial in the Global Times or read the rantings of a nationalist on an internet forum in China, they would have seemed incredibly different to the relatively restrained tone of the Foreign Ministry. That's just not true now. I think the Global Times sounds pretty similar to the Foreign Ministry on your average day.

There's still light between them. When the China-India border tensions were at their peak, there were internet users suggesting Foreign Ministry officials were being weak and traitors and weren't standing up for the motherland.

There's still pressure on that front, but a lot of it has been solved by firstly Xi Jinping's move toward nationalism and the tone that that's helped set for China's foreign relations, but then also the Foreign Ministry has embraced Wolf Warrior diplomacy.

You can see just how popular that seems to have been, from t-shirts with Yang Jiechi’s nationalist slogans on them to viral clips and fan sites for senior Chinese diplomats.

Jason Zhou: I guess one last question I have is whether over the last six months we've seen a decline in some of the more undisciplined or unhinged social media presence by Chinese foreign diplomatic accounts.

I remember [in 2021] someone at the embassy in Ireland posted something about a wolf and a lamb and about China not being a wolf but also not being a lamb or something.

I feel like there's been less of that in recent months so maybe they've actually realized how unprofessional it looks and tightened up on it?

Peter Martin: The embassy tweet you're referring to was a classic of its genre, and really, really, confoundingly confusing.

Anecdotally, I think that there probably has been a tapering of Wolf Warrior tactics on Twitter. I know there's a study being done at the moment at University College Dublin on how far that change has been real and in particular how far Xi Jinping's remarks at a Politburo study session over the summer, where he talked about how China needs to cultivate the more lovable image, has influenced the tone.

My impression is that some of that has been reduced a little bit. But you still hear statements from senior Foreign Ministry officials saying that America is sick or America's political system is sick - things that really wouldn't have been at home in Chinese diplomacy five, 10 or 15 years ago.

I think the theater, abrasiveness and assertiveness have continued, but on that tactical side, especially on social media, things have come down a little bit.

That's a tactical decision but it's also a reflection of policy as well. After a period of great uncertainty at the beginning of the Biden administration, where the two countries were trying to suss each other out, they're starting to have more regular meetings for senior leaders and have the militaries talk to each other.

I think from Beijing's perspective it's not helpful to have diplomats derailing that process. It's a tactical decision and it also reflects policy.

Want more? Check out the full podcast here, as well as the part one podcast and transcript.

Thank you for reading. ChinaTalk grows only through word of mouth. Please consider sharing this post with someone who might appreciate it.