Where Japan Goes Next

Inside Japan’s political upheaval

Editor Lily is in Bishkek next week! Drop us a message if you’re in town.

What is going on in Japanese politics? What do the election results mean for Japan’s future? Did Trump’s tariff pressure play a role in Prime Minister Ishiba’s rumored resignation?

To find out, ChinaTalk interviewed Tobias Harris, creator of the Observing Japan substack. Tobias first appeared on ChinaTalk in 2022 to discuss his excellent biography of Shinzo Abe.

Our conversation today covers…

The political mechanics behind Ishiba’s resignation and the trade deal with the US

Why the LDP fell into crisis after the assassination of Shinzo Abe, and how the Japanese public responds to scandals

What the latest results in the upper house election tell us about domestic Japanese politics

The political parties trying to capitalize on the power vacuum left by LDP decline, including communists, far-right populists, and pro-labor TikTok conservatives

How the US, China, and even Russia have influenced Japanese domestic politics in the post-Abe period

Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app.

Thanks to the US-Japan Foundation for sponsoring this episode.

Japan Makes a Deal, Ishiba Resigning?

[This bit we recorded weds afternoon]

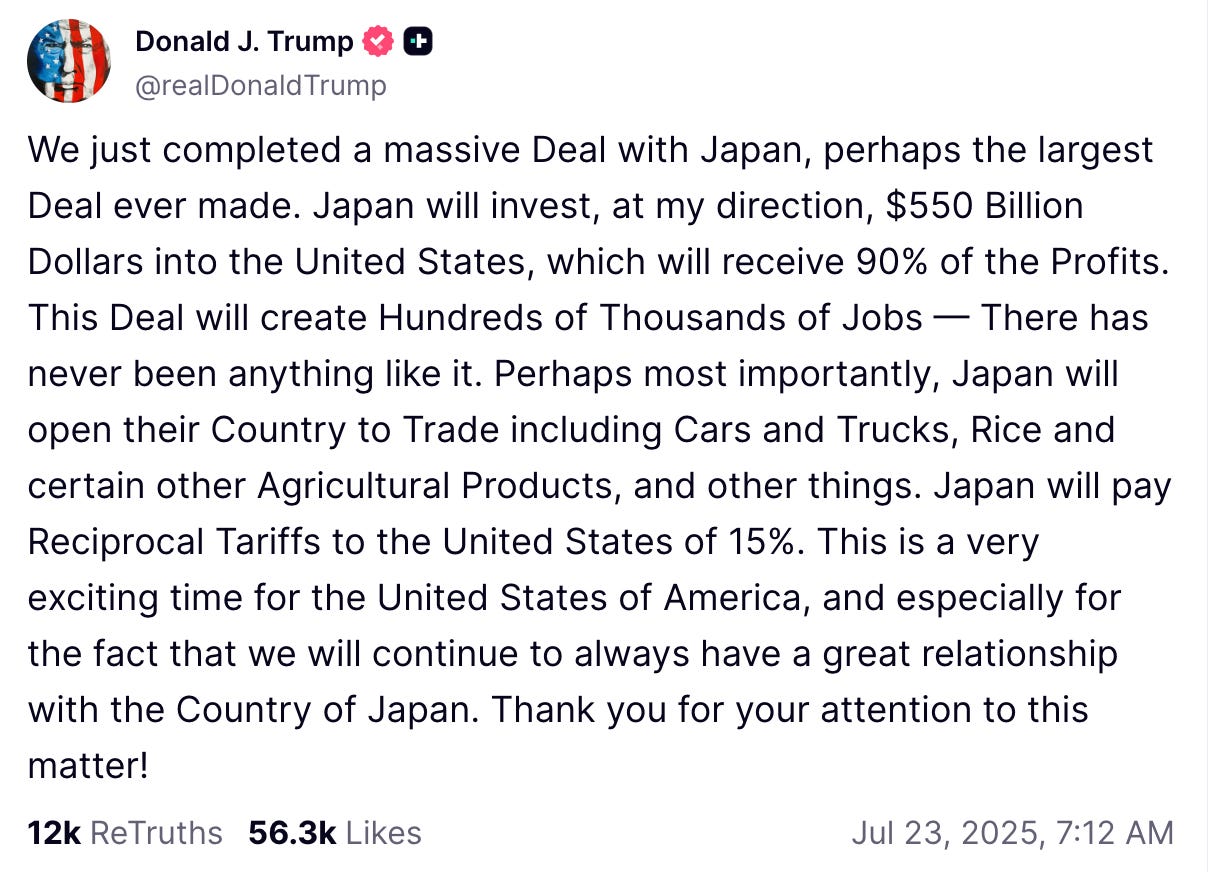

Tobias Harris: Well, the first thing that happened after we recorded was that a US-Japan trade deal was announced via a Truth Social post by the president. Everyone was wondering if we were going to get that deal, and then we did. At first, it looked like it was going to be an entirely one-sided deal, but then details started trickling out. It’s actually probably about as good a deal as Japan could have hoped for.

Then, a few hours later, I was getting ready to go to bed when my phone rang. It was Bloomberg in Hong Kong asking if I could be on TV in 20 minutes. They had just gotten news that Prime Minister Ishiba was going to resign. I looked at my phone and saw there was a scoop from the Mainichi Shimbun, a center-left daily newspaper. Technically, it wasn’t that he was resigning — it was that he had told sources he was planning to announce his resignation within the next few weeks. It wasn’t quite “I’m going to resign,” but it seemed pretty definitive.

It’s now been pretty much confirmed by other sources. Ishiba himself has not officially confirmed it, but it seems like it’s more or less a done deal that in a couple of weeks he will officially confirm that he’s leaving. The other thing that has happened in the interim is that his support in the party is collapsing. There are a lot of calls for him to quit, and they’ve become much more vocal after the story broke. He looks like he’s done, even if he doesn’t seem to entirely know it yet.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s do a little Japanese media literacy lesson. If you’re saying people got more vocal after the story came out, it seems like there are a lot of folks who have some incentive for a story to come out if they want to see change happen. Do you buy it? Is there a way for the tail to wag the dog here, where a story comes out even if it’s not actually what he was meaning, and then that emboldens the LDP membership in such a way that it’s hard for him to keep everything together?

Tobias Harris: I’m not ruling that out entirely, although I wonder whether the trade deal announcement was actually the more important development. To some extent, the fact that there hadn’t been a trade deal and that you had this August 1st deadline looming over everything made some people reluctant to say Ishiba should go because they didn’t want to jeopardize those talks while they were ongoing. There was hope that you’d get some deal done that would spare Japan from 25% tariffs on August 1.

But once that deal was announced, essentially Ishiba made himself obsolete. All the people who were holding back because they didn’t want to hurt the trade negotiations — well, now that those are done, you can focus on Ishiba’s shortcomings as a leader of the LDP and his inability to manage the Diet without worrying about the trade talks. That was really the more important trigger. Once that was announced, a lot of hesitant critics within the party now feel more emboldened because they don’t have to worry about those concerns.

Jordan Schneider: I guess Ishiba needed more of that Netanyahu energy of taking the country down with the ship in order to preserve his political future by blowing the trade deal up. But let’s look forward a little bit. How does one become the next prime minister of Japan?

Tobias Harris: You already now have a number of aspirants getting ready, waiting for the flag to go up when they can start being formal candidates. You had nine people run last year, and I suspect we’ll see a number of the same candidates who ran last year run again.

The question that the LDP is going to have to figure out this time around: normally when you have a leader quit midway through their term, the LDP has emergency rules in place to do a very abbreviated campaign that doesn’t leave a vacuum for a long time. That basically limits the role that rank-and-file dues-paying members have.

Normally, last year you had this month-long campaign where the candidates crisscrossed the country, held forums, and met rank-and-file members because ultimately the rank-and-file dues-paying members of the LDP would vote. Those votes would determine a portion of the votes in the first round of voting, with the other share going to LDP lawmakers.

When you have an emergency election because someone’s resigned, you would not necessarily have that public voting. It generally will be more the lawmakers and party officials at the prefectural level basically making the decision.

Given that the party is having a major loss of public confidence, there’s actually some pushback now saying that we should set the rules for this election to be like a normal election. They want to give the rank-and-file a say in the matter and try to have a full public vote again. The goal is to try to move toward reconnecting with the public to find someone who actually might appeal to more people instead of having this be a behind-closed-doors, proverbial smoke-filled room decision.

Jordan Schneider: That’s a good note to end on. As a note for the audience, the rest of this interview is still very much relevant to understanding the trade deal, the political pain the LDP finds itself in, and the national constraints the Japanese government is operating under.

LDP in Crisis and Japanese Political Economy

[starting from here we recorded Tuesday AM]

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start the clock at the Abe Shinzo assassination. What has happened in Japanese politics since then?

Tobias Harris: That was three years ago. During the last Upper House campaign, Abe was doing a campaign stop at a train station in Nara and was assassinated for reasons that at first were unclear. It quickly became clear that it had to do with his relationship with the Unification Church, which set off a whole discussion of the Unification Church’s role in Japanese politics.

We’re not going to talk about that because it’s less important than the impact the assassination has had on Japanese politics subsequently. I would argue that at the moment Abe was assassinated — even though at that point he had been an ex-prime minister for just under two years — he really was arguably the most powerful figure in Japanese politics.

That’s because he was the head of not only the LDP’s largest faction, but also really the head of the party’s largest ideological tendency. Basically, the right wing of the party was arguably dominant, even though you had a more liberal prime minister at that point in Kishida Fumio. Abe really was in a position to set the agenda because here was this very notable, prominent, powerful ex-prime minister who also was a faction boss and commanded a lot of media attention. When he opened his mouth, everyone was forced to listen and pay attention to what he was saying. He was a tremendously powerful insider political figure who controlled a lot of votes within the party and was instrumental in getting Kishida elected in the first place and then sustaining his government.

You’ll notice that when Abe died and was out of the picture, you essentially lost a fundamental supporting pillar of LDP governance. You had a few unintended consequences where his death meant basically the exposure of the relationship to the Unification Church. That was one scandal that hit the LDP that they weren’t really ready for.

Then you had a second scandal that came in the wake of that. When Abe was gone, the leaders of the Abe faction who followed him basically decided to start this practice that Abe had ended. Members of the faction had these fundraising parties, and they had this practice where everything that you raised in excess of a certain quota that went to the faction was kicked back to you. They decided to start doing that, but those kickbacks weren’t reported according to the requirements of campaign finance law. This turned into a huge scandal that destroyed the faction system essentially. It basically led the party to say, “Okay, that’s it, we’re done with the factions.” That was pretty much a direct consequence of his passing.

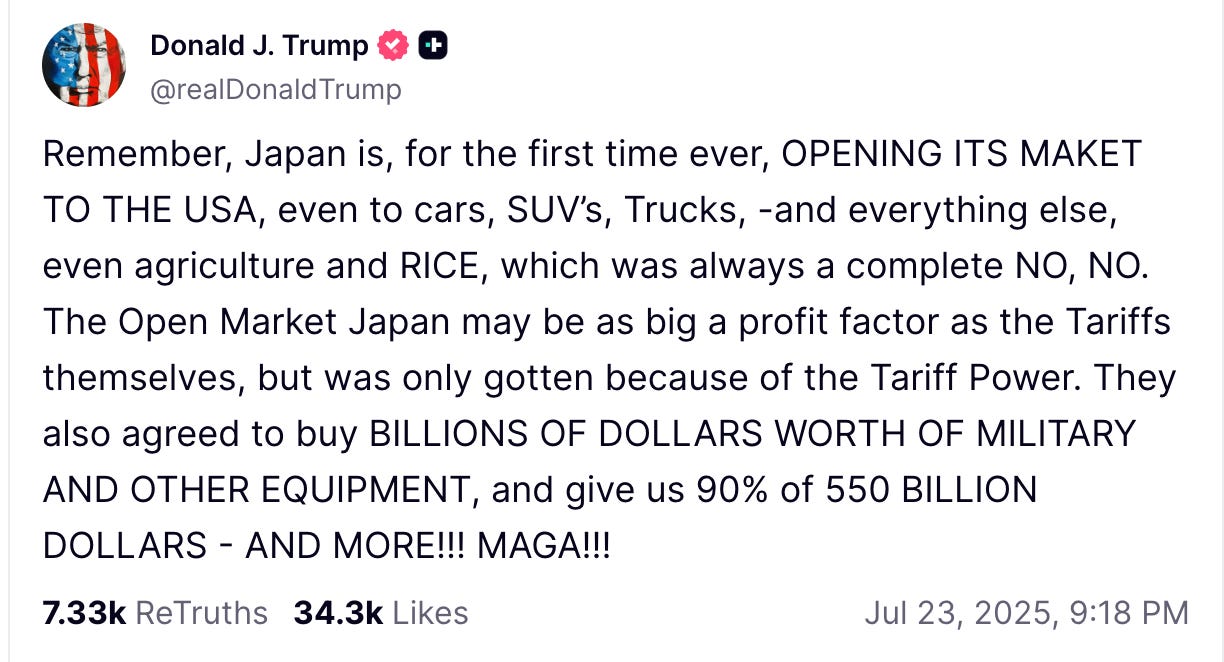

As a result, the LDP forfeited a ton of public trust and has performed poorly. They did fine in the 2022 Upper House elections that happened right after he was assassinated. But in the general election last year and now the Upper House elections this year, the LDP lost significant ground. The number of votes that it got in the national proportional election portion — the LDP got 6 million fewer votes this past Sunday than it did in 2022. That’s just an enormous collapse in trust in the party.

There’s some question about precisely measuring how many of those votes are from moderate people who are dissatisfied with the direction of the party versus people on the right who don’t like the post-Abe direction of the party and have been voting in protest. But there’s a real loss of confidence and trust in the party. It has basically meant that the LDP has not only lost public confidence — it now has lost control of both houses of the Diet. You almost have this death spiral feeling going on right now.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s step back and do a little more Japanese political economy fundamentals, because you just threw a lot at the ChinaTalk audience. Can you explain how the Japanese political system works, and what made the Abe era unique?

Tobias Harris: The main thing to appreciate about the Abe era — which was eight years of him in power, and then you have several extra years of him as a powerful ex-prime minister — is that this decade, when he returned to power in 2012 onward, was really the capstone of what had been at that point basically 20 to 25 years of attempts by reformers in Japan to make Japan a much more centralized, top-down political system.

When the LDP was in its Cold War era period of dominance, it was not a top-down system. It was very much — people at times talked about the LDP almost as a coalition government because its factions were very autonomous and competed for power and had different beliefs and different personalities. They were almost like mini parties in and of themselves. The LDP historically was strong, and the governments that it chose were generally pretty weak and had weak prime ministers who were considered first among equals, but they did not have a lot of agenda-setting power relative to other players in the system, including the bureaucracy.

At the end of the Cold War and heading into the end of the century and the beginning of the new century, you had a lot of reformers who basically said, “This is not sustainable. We need strong prime ministers who can navigate a challenging global order because things are changing. We have friction with the United States. We have China rising. There are challenges that require more capable leadership."

You had a series of reforms really going back to the early ’90s to try to make the system much more top-down, to create much stronger prime ministers. Ultimately, Abe was the product of those reforms. You had electoral change, administrative reform, and various other political reforms to basically ensure that the Prime Minister would have the ability to set the agenda, dominate the political system, and basically say, “This is what we’re going to do,” and then follow through on that.

It was a bumpy process to get there, and you had some two steps forward, one step back when it came to actually seeing the Prime Minister reach that point. But 2012 really is when Abe comes back, has really thought about how to govern and how to use the powers that these reforms have produced, and then sets about saying, “Here’s my agenda. I have large majorities in both houses of the Diet, and I’m going to set about doing that.” By and large, he did. He spent eight years saying, “Here are my economic policies, and I’m going to really work on putting those into practice. I’m going to strengthen Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. I’m going to press forward with — if not outright constitution change — some changes to national security laws.” He basically did as promised.

That really explains the 2012 to 2022 decade. What we’ve learned over the last several years was how much that depended on that political foundation, which was the LDP consistently winning national elections and ensuring that it had those majorities with which to govern. That in part also depended on a weak opposition. On all of those fronts, things have started to churn. Some of that is really — like in a lot of Japan’s peers in the G7 — the way in which COVID scrambled everything and changed the political landscape that the parties were operating in. What had been a very friendly landscape for the LDP post-2021 became a progressively tougher landscape for them to operate in.

Jordan Schneider: What are the frustrations of the electorate that are universal? And what are the more specific gripes that people have had over the past few years with the governing party?

Tobias Harris: Like in pretty much every other democracy post-COVID, the problem is inflation. Japan had wanted inflation for a long time. Abe was a reflationist — inflation was the thing they wanted. But the inflation they’ve gotten has not necessarily been the demand-pull, higher wages leading to higher consumption, leading to steady increases in inflation. It was more the supply shock kind of inflation from imports getting more expensive due to a weaker yen because you’ve got divergence in monetary policy between Japan and other countries.

The yen was weak, and Japan imports a lot of food and energy, and that was passed through to consumers. That really has hurt. Getting more of the cost-push inflation has really eroded household incomes. You’ve really seen a lot of pain from that, a lot of frustration, and that certainly contributed to the LDP losing last year. If you look at exit polling this year, it was overwhelmingly the issue that voters cared about most this time around.

The LDP hasn’t really had a good answer to that inflation — the Bank of Japan has started raising interest rates, but it’s still relatively slow, and you still have a pretty big divergence in monetary policy, so the yen has still been relatively weak. Households feel squeezed. You’ve had a lot of effort to try to get wages up, but it’s a difficult process. It is not something that’s happened fast enough to make people feel like they have more money in their pockets. The LDP has just been punished for appearing not to have done enough.

This was a problem last year in particular, where you had this big scandal that showed the LDP skirting campaign finance law and looking like it was taking care of itself at a time when people felt poor. The confluence of those issues really hurt the LDP. This year was probably pure inflation — inflation is up, real incomes haven’t kept pace, and the LDP really has suffered for that.

Jordan Schneider: The kickbacks, if I recall, were in the hundreds or thousands of dollars, right?

Tobias Harris: Yeah, like most Japanese political scandals, it’s more about the behavior than the amount of money involved.

Jordan Schneider: Is there an Epstein-Japan connection? I just asked ChatGPT. It gave me Joi Ito, who’s apparently a VC who took $1 million from Epstein, and then Suga was going to put him as the head of some digital agency, but had to pull it back.

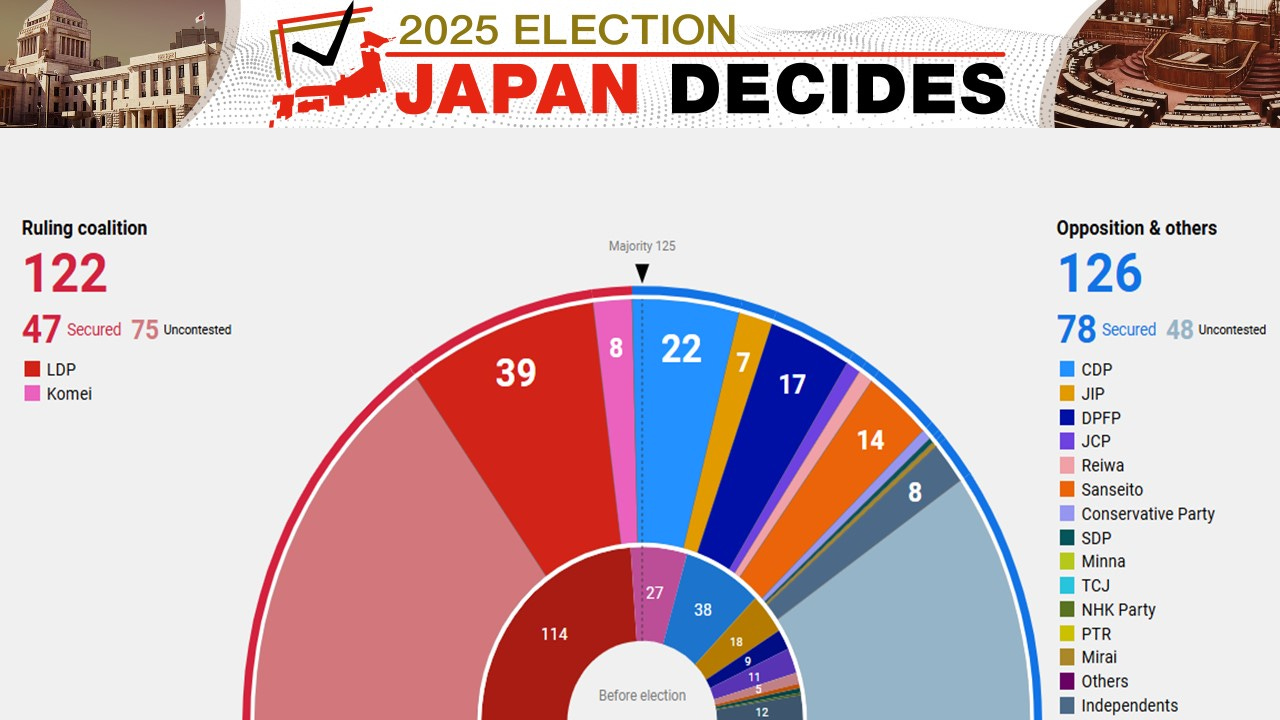

Tobias Harris: Maybe this is a good segue to talking about the party that everyone is talking about now, which is Sanseitō 参政党, the new far-right party whose leader says that he views his peers as the AfD, Marine Le Pen, and Reform UK. They are thoroughly steeped in online memes and online political discussion in the United States. They’ve trained their activists in English so that they can follow online debate. There is some leakage of American online political culture into Japanese discourse that way.

Sanseitō also — just going back to how COVID and its aftermath changed Japanese politics — is one very tangible way in which it changed because it really emerged as an anti-vax group, and anti-vax, and then from that, opposing anti-globalist conspiracy theorizing. It has now branched into other, more traditional Japanese far-right politics, and is now a new force in the political system.

Jordan Schneider: How weird is this?

Tobias Harris: There are a few ways of answering that because I personally have, on multiple occasions, pushed back against the idea that Japan has been uniquely resistant to populism. I just don’t think that’s true. Japanese populism has often looked different than it looks in other countries because it hasn’t generally been xenophobic, just because you haven’t had a foreign population to really target with it.

But you had populism, because when the bubble burst in the early ’90s, there were a lot of elites to get mad at. You had anti-LDP backlash, you had anti-bureaucratic backlash, you had Koizumi govern as a populist. The literature on Koizumi constantly talks about how he governed as a populist, but the elites that he was using populist tools against were members of his own party because he was targeting these rural fat cats who had relied on pork barrel spending and support for building bridges to nowhere and useless roads that nobody was using.

Populism in Japan has pretty much — certainly post-Cold War — been an urban phenomenon. It is urban voters who feel like they don’t have enough political power in the political system and that they’re slighted, their interests are slighted, that their quality of life has degraded and that the political system is skewed against them. Repeatedly you have had parties that are populist. You have Ishin no Kai, this Osaka-based party that emerged about 15 years ago and has tried to become more national — very much a populist party, anti-bureaucratic, anti-teachers unions, anti-national government. This is not a new phenomenon.

What is new about Sanseitō is the degree to which anti-immigrant, anti-foreign population rhetoric has been part of its appeal. That’s because you do have a bigger — you now have a bigger foreign population in Japan than they’ve pretty much ever had. Thanks to Abe, actually.

It’s on my to-do list of essays I want to write. I want to write the story of how Abe created Sanseitō through his embrace of — if not, he would not call it immigration — it was a de facto guest worker program. Opening the door, simultaneously opening the door, but as in many other countries, not really wanting to talk about it. Basically trying to put a lid on the issue and not have a big debate within the LDP about it, he basically allowed discontent over this to simmer and to grow.

Essentially the business wing won out, right? Because business in Japan wants — they’re basically having trouble getting enough workers to do a lot of jobs, and they wanted it. But Abe basically didn’t get enough buy-in from his own base, his own right-wing base, and let the problem simmer. Now the LDP is essentially paying the price for that set of choices that Abe made.

Jordan Schneider: What’s the complaint about immigrants if unemployment is zero?

Tobias Harris: For example, there’s a left-wing party, Reiwa Shinsengumi, that is also anti-immigrant because they think that relying on foreign workers suppresses wages. Basically, it’s a tool by the business community to suppress wages. There’s a bit of a horseshoe effect going on there where the left-wing populist and the right-wing populist both are opposed to foreign workers for their own reasons. This is not something that’s unique to Japan — you see similar politics in other places as well.

But it’s more about how they fit in, right? There have been some highly publicized stories about foreign communities in certain places where they’re not following the rules about garbage disposal or they make too much noise. There’s an issue with Japan’s growing Muslim population and the fact that they need a lot of space for their cemeteries. That is something generally that the local population — Japanese cremate more. There are just a lot of culture clash issues that come with this.

These issues come with Japan just having — yes, the foreign population is 3% of the whole, relatively small, but it’s increased pretty significantly in a fairly short period of time. There’s going to be friction as a result of that.

But it’s possible to overstate the degree to which that’s been a factor. A lot of the press coverage of this election outside of Japan has focused on this party that has xenophobic appeals and came out of nowhere, and clearly that shows that this is a big issue overall. You look at the exit polling and overwhelmingly it’s inflation, not the question of Japan’s foreign population.

Sanseitō forced other parties to talk about it more than they had been, and certainly their own voters care a lot about this. But I’m not necessarily sure that it’s the only reason that people voted for Sanseitō because they were also out calling for very big tax cuts and limits on Social Security premiums and basically trying to put more money in people’s pockets, which is the main issue for a lot of urban voters, which is where they did best. This keeps with this idea of Japanese populism being primarily an urban phenomenon.

It’s too simple to say that this shows Japan is now joining the anti-immigrant wave everywhere else and that it’s as salient as it’s been in other places. It’s too soon to say that.

Jordan Schneider: To what extent is the demographic crisis something that has seeped into political discourse? Something politicians actually try to have plans about?

Tobias Harris: It’s been part of political discourse for 30 years, and they’ve tried all different ideas and are constantly proposing this subsidy and that child allowance and lots of other ideas. I don’t think Japan has had any more success figuring out how to encourage people to have more children than any other democracy facing a demographic crisis. They’ve just been at it for longer.

There is a feeling, in some ways, that Japan has passed a point of no return to a certain extent, where just a certain amount of decline at this point is baked in. Every year, the number of new births is setting new records for numbers that you haven’t seen since the late 19th century.

The crisis is here. In some ways, now, there are two different sides of it because there’s the “how do we encourage people to have more children?” But then there’s also the question of how to deal with the consequences of demographic decline now, in the moment. “How do we deal with the fact that you have rural communities depopulating, and how do we ensure that there’s still service provision in these communities? How do we entice young people to actually want to go live there? That’s a whole other set of policies that have been debated for a long time.

It’s baked into politics — everyone has to talk about it, but I don’t know if anyone’s got any brilliant ideas for how to fix it.

Jordan Schneider: I think it’s just getting American YouTubers to continue making those incredibly viral videos of how they fix up the beautiful house in the valley or whatever, which is a shockingly popular genre.

Let’s talk Russia connections. There was a whole foreign influence arc in the most recent campaign. How did that play out? What’s your read there?

Tobias Harris: It kicked off when a Sanseitō candidate went on Sputnik News. Sputnik News posted that all over Twitter, and Sanseitō then basically said, “Oh, this wasn’t authorized,” and they fired someone and tried to sweep it under the rug.

Then you had the Ishiba government actually coming out and saying, “We have evidence that says there were foreign bot activities on Twitter promoting basically disinformation about the foreign population in Japan and basically trying to find these wedge issues to divide Japanese against each other and promoting Sanseitō.” Sanseitō denied that there was any connection or anything to do with this.

The LDP in the last few days was raising questions about what exactly was happening here. I have a pet theory that suggests that, compared to some of the polling that we saw, Sanseitō actually underperformed a little bit. It looked like they were actually on track to win at least a few more seats than they did. What I wonder is whether in the final days, the Russia connection may have pushed some voters on the margins away from them.

Basically, there was no polling after the Russia allegations came out, so we wouldn’t really have seen that show up until election day, until we actually saw the numbers. It’s possible that there may have been some races that went differently because of that, but we don’t know for sure.

But I think that’s something that the Japanese public is likely to take seriously. I don’t think there’s a lot of good feeling towards Russia at the moment. If it turns out that there is more there, it is likely to shape opinions of Sanseitō in a pretty negative way.

It’s probably also worth mentioning here — and this is something that maybe people don’t appreciate — Sanseitō ran in an election for the first time three years ago. It won one seat in the Upper House three years ago. It won four or five seats in the Lower House last year. This is a party that does not have a big presence or hasn’t until this election. As a result, it was very fringe. It did not get a lot of mainstream coverage. It did not get a lot of mainstream scrutiny. Everyone would just dismiss them as this goofy party on the fringes.

Most of the attention that it has gotten has been in the last five weeks. It really did not start climbing in the polls for this election until about five weeks ago. The Japanese media basically has not even begun combing through their dirty laundry.

Jordan Schneider: If people get scandalized by single $1,000 illicit campaign finance violations, then as long as that backbone of integrity in the electorate is there, then you wouldn’t be shocked to find other things going on with these fun YouTube influencer politician types.

Tobias Harris: There was certainly more smoke than just what the government was saying about bot activity. One of the big weekly tabloids actually looked through their finance records and found a series of payments over the course of a few years to some PR company called Vostok that basically changed its office location a few times. No one had any idea what this company was that they made payments to for PR help over the course of several years.

Jordan Schneider: How many Tobias Harrises are living in Vladivostok giving deep domestic Japanese political takes on how to position to win those seats?

Tobias Harris: That kind of information was out there for anyone to report on for years. Those were payments going back to basically the beginning of the party. That just tells you that they really are only now going to start getting more scrutiny.

It’s too early to say, “Oh, this is a party that’s definitely here to stay and is going to be a fixture on the landscape now.” We’ve seen a lot of parties come and go in Japanese politics for a long time, and a lot of populist parties that look like they have the wind at their backs and are destined to change everything. Building a sustainable, durable party is not something that can happen over one or two cycles. This is a longer-term process. We’ll see what happens with them after this.

Jordan Schneider: All right. We’re going to take a few more vitamins. How are parliamentary elections structured in Japan?

Tobias Harris: Well, if we’re talking about the Upper House elections that just were held, they’re a little complicated. The Upper House has 248 seats, like the Senate. You don’t get all of the Upper House elected at the same time — they serve six-year terms. Half the house is on one six-year cycle and the other half is on another six-year cycle. Half the house every three years is up for election.

What you have, like in the Lower House, is essentially a mixed system where a portion of the election is for PR seats. In the Upper House, it’s a national proportional representation list. Each party has its slate. Voters have the option of voting either for a party or for a candidate on one of the party’s lists. That’s 50 seats for PR.

For the remainder, it’s a mix of single-member constituencies, basically representing each prefecture, but the prefectures get more seats or fewer seats depending on their population. Tokyo elects six members at a time to the Upper House, but most of the country only elects one member at a time. In fact, there are four prefectures that essentially elect half a representative because they’ve been fused with a neighboring prefecture because they have too few people.

That’s 32 single-member constituencies and then the remainder — the remaining 13 prefectures have multiple members ranging from Tokyo’s six to some that have two. Every voter gets two votes: one for their constituent representative, one for someone from the PR list or for a party in the PR list. That makes up the constituency for the Upper House. We can talk about the Lower House too, but if you want to pause and talk about a little more about the Upper House, we can do that as well.

Jordan Schneider: What can parties who aren’t in power do?

Tobias Harris: They can try to get more seats. In terms of their role in policymaking, it’s complicated because generally Japan — historically, we were talking about the 30 years of reform and trying to change the system and making the system more top-down — historically Japan was not a textbook Westminster democracy where the prime minister, if they have a majority, is an elected dictator and can do whatever they want as long as they have a majority. Precisely because the LDP as an institution was so strong and the prime minister had to defer to other players in the system.

There were stretches during LDP rule where actually there was a ton of backroom negotiations between the parties, between the ruling and the opposition parties. It was never just a textbook “government has the votes, it can do whatever it wants.”

What happened under Abe was that you did get more of a textbook Westminster-style democracy where you did have the Prime Minister wanting to do this, he’s got the majorities, he’s going to do what he wants. Maybe he’ll defer if public opinion is negative — he’ll make some concessions to public opinion — but basically was not conceding much to the opposition. There wasn’t really that much the opposition could do about it.

Now, it’s changed again because after the general election last year, the LDP-led government does not have a majority in the Lower House. It has had to actually concede quite a bit of power to the opposition. In practice, that has meant the leading opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party, controls several very important committees in the Lower House. That gives it a lot of agenda-setting power and a lot of ability to control how legislation moves, the pace that legislation moves, when votes get scheduled, how long debate takes.

The opposition actually at the moment has quite a bit of power. Now, after Sunday’s results, you’re going to see something similar, at least for the time being, in the Upper House where if they want to do anything, they’re going to have to negotiate with the opposition parties to get something on the legislative agenda to ensure that the votes exist to pass it. The opposition parties actually have quite a bit of power to slow things down and to block the government’s agenda in a way that they did not have during the Abe years.

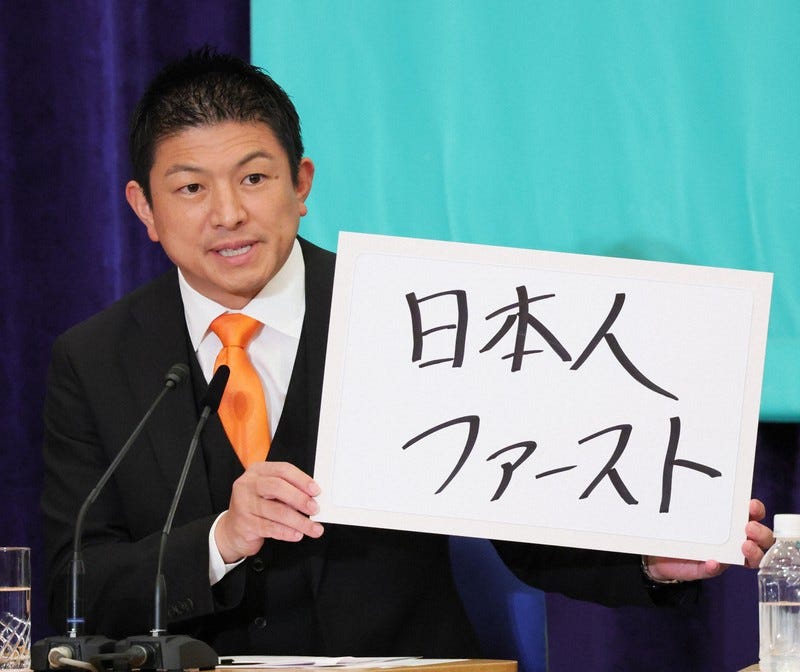

Jordan Schneider: All right. Back to the horse race, folks — Tobias’s favorite new entrant to the scene, Democratic Party for the People. What’s their deal?

Tobias Harris: They’ve been around for about seven or eight years now. They are a splinter from the former Democratic Party of Japan, which was from when Japan had this brief flirtation with two-party democracy and even had an actual change of ruling party via an election — crazy idea, doing that in a democracy.

In 2009, when the Democratic Party of Japan won a huge majority and swept the LDP into opposition, and when they went back into opposition in 2012, they basically were almost powerless. Abe ran roughshod over them. They had no appeal to the public. Eventually what happened is that it split into competing post-DPJ parties. You have the Constitutional Democrats as the more center-left party, and then the Democratic Party for the People is a smaller, more center-right splinter party, basically.

It’s actually funny because both the CDP and the DPFP (some people abbreviate it as “DPP,” but that’s already taken by the Taiwanese Democratic Progressive Party) are both still backed by organized labor.

The big organized labor federation, Rengo, is always calling the leaders of the DPFP and the CDP into her office, basically, and saying, “You two have to cooperate more. You two have to stop fighting. You two have to stop working at cross purposes,” which is just funny.

What the DPFP actually has tried to do in recent years is essentially trying to do this identity change where it started as this party backed by organized labor, but a little more conservative on some things. More conservative on national defense, they’ve been pretty pro-nuclear energy, just more friendly to Abenomics-style policies instead of welfare state center policies like the CDP.

What they’ve been trying to do is pivot to become a party of the urban, young working class. The same voters that Sanseitō was trying to appeal to. Basically trying to be a voice for these urban working young workers who generally aren’t well served by the existing parties. The political system has generally not given much voice to these people. They don’t really have a political home.

They’ve been trying to make this acrobatic move where without alienating the organized labor supporters, which are still important in some particular constituencies for the DPFP, without losing that support, they’re trying to make this pivot to being this party of young urban voters. It’s actually worked pretty well now for the last couple of elections.

They have generally been much savvier at social media. They really have tried to do this thing where they try to do campaign rallies almost in the hope of producing viral content that they could then post on YouTube and get shared a lot and get people talking about it. Their leader, Tamaki Yūichirō, is always doing these things where he’s holding his phone out and riffing and taking questions from people. They’re trying to be a little more like meeting young voters where they are.

They’ve had a lot of success with it. Their success this election was bigger in important ways than Sanseitō’s. Because they have more seats in the Lower House, they’re a much more important player going forward than Sanseitō will be at the moment.

They’re part of the picture. They’re an important player. They may end up as part of a ruling coalition depending on how things break. We’ve got to keep an eye on them as well.

Structural Stagnation and the Impact of Foreign Policy

Jordan Schneider: All right, back to the LDP. What happens next with them?

Tobias Harris: The party’s in crisis.

Jordan Schneider: To start off, who’s voting for them? Everyone seems upset with the LDP.

Tobias Harris: They’re still the biggest party in the country by a long way. Don’t underestimate that — they still have the most seats and wield considerable power in many different areas.

What’s happening now is that they’ve gone through several phases since 2012. Abe tried to make it a much more coherent, ideologically conservative party that could still compete nationally and win in many places. To some extent, he was successful in that. But his success depended heavily on voter apathy.

If you look at all the elections held from 2012 onward, turnout was really low. This allowed Abe to win elections on the strength of the electoral machines of the LDP and its coalition partner Kōmeitō 公明党. Both parties are very good at organizing their votes and getting their voters out to the polls. With low turnout — particularly when independents stay home — the LDP has been able to win. That’s how Abe won six national elections with record low or near-record low turnout in pretty much every one of those elections.

He was basically taking advantage of voter burnout. During the first decade of the century, you actually had many very high turnout elections. People were excited about Koizumi, and then they were excited about competition between the LDP and the DPJ, which produced some pretty high turnout elections. But after the DPJ failed in office and left in 2012, there was a lot of exhaustion. Voters were fed up with the DPJ. Many independents weren’t terribly excited about Abe and the LDP and didn’t feel like they had anyone to vote for. Turnout fell.

The LDP can’t take that for granted anymore. Turnout rose six and a half percentage points this election compared to 2022’s upper house election. Independents are paying attention again. The LDP has struggled to keep its own supporters and get them turning out for a mix of reasons: the corruption scandals, and conservatives who think that both Kishida and Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru are too liberal and have turned from the true way that Abe had outlined. They’re punishing the party.

You have many voters who might have voted for the LDP in the past, but have decided to start punishing the party. You also have voters who sat out previous elections who are now coming back. Many of those appear to be younger voters, and they’re also voting to punish the LDP because they feel their lives haven’t gotten any better. The party has been in power uninterrupted for 13 years — what do they have to show for it? All of this has created a situation where the LDP does not have a majority in either house of the Diet.

Jordan Schneider: Is it a personality thing? The fact that we’ve got Tarō Asō at 84 years old still trying to call shots doesn’t give me a ton of confidence.

What’s the incentive structure for a young, upcoming charismatic politician to try to revive this giant carcass of a party, as opposed to going somewhere different that’s maybe more nimble and more easily bent to the things they’re interested in? Are there deep structural reasons for the LDP not to be able to get it together, or are there people with views and enough folks who see the writing on the wall that you think this organization has the capacity to rebuild a mandate?

Tobias Harris: The first part of that question is important — there is a feeling that generational change has not happened. Look at when people entered politics — Abe was elected in 1993, Suga in 1996, Kishida in 1993, and Ishiba entered politics in 1986. There’s definitely a feeling that the party has been led by people who’ve been around forever and are refusing to release their grip. This sounds familiar in some other contexts we could discuss.

There’s a feeling that they’ve really frustrated the ambitions of younger people. In some ways, this was one of Abe’s shortcomings — he ended up filling his government with people who were loyal to him, people he trusted. These were largely people who came up in politics around the same time as him. He didn’t do enough to really cultivate that next generation, to foster talent, or to raise up the next generation of leadership.

It’s ironic that last year, the young, shiny face of generational change — one of the faces of generational change in the nine-person leadership election — was Kobayashi Takayuki, this young, hawkish guy. But he’s 50 years old. That’s what counts as young and as the voice of generational change in the LDP.

There’s a real feeling that the party has not confronted this issue, has not cleared out some of these voices who’ve been around forever, and they’re paying a price for it. It means they’re out of touch. It means they don’t really have a way of using social media effectively. All these other parties are running circles around them when it comes to actually communicating with younger voters and meeting younger voters where they are — delivering information in ways that are relevant to them. The party just feels very out of touch in that way.

The ironic thing is that when I was looking at the general election last year and the candidates that were running, the LDP still has a shocking ability to recruit young people as candidates. That’s probably a hangover from the fact that the party was as dominant after 2012 as it was. During the years when you had this nascent two-party competition, the DPJ actually did have some success attracting young people who wanted to enter politics because they could say, “We might actually have a chance of making a difference in politics and winning. Here’s this new and up-and-coming party, and there’s a place for me in that.”

After 2012, everyone said, “This party’s going nowhere. Why would I want to run for them?” That actually created a problem for the CDP, where not unlike the LDP, they also haven’t had generational change. The CDP is now led by Noda Yoshihiko, the last DPJ prime minister who came back into the CDP’s leadership last year. There’s this feeling that the party is still dominated by all these people who were around leading the DPJ when it was in power. You haven’t had generational change there. They haven’t had an influx of new talent.

One question going forward now — you do have these new up-and-coming parties among the opposition ranks. Does the DPFP get a big surge of new people wanting to run? I’ve seen that. If you look at the candidates they’re running, you are getting people in their twenties and thirties who quit their business jobs and say, “Yeah, I’ll run for office. Why not? I’ll give it a shot."

You are seeing more of that. Of course, Sanseitō has this huge digital grassroots organization that is bringing outsiders into politics. Now, as the LDP is in this crisis and maybe headed into opposition at some point, you may see more of that and more second-guessing: “Oh yeah, maybe I will go run for a different party instead of joining the LDP.” That’ll be something to watch. Is there more diversity in the choices that political aspirants take?

Jordan Schneider: How does one get to run for office for the LDP? Are there the equivalent of Open Primaries? Is it all decided by party central? How does it work? And once you’re elected, how much agency do you have to fight the man or kick out a prime minister?

Tobias Harris: Traditionally in Japanese politics, to enter politics you had to have the “three bans” 選挙の三バン, which refers to jiban 地盤 (a local support base), kaban 鞄 (financial support, basically referring to the bag of money you have, since kaban means bag), and kanban 看板 (name recognition).

What these have added up to is basically hereditary dominance, because the easiest way to enter politics was having name recognition because you’re the son of a politician who’s retired. Jiban — your father (usually father, maybe very occasionally mother) has passed down a support group, basically the electoral machine that’s going to get out the vote for you. Kaban — your parents have been raising money for a long time and are able to pass down that fundraising prowess to you.

You had really prominent hereditary politics for a long time. To some extent that has continued even after electoral reform in the 1990s when Japan switched to predominantly single-member districts in the lower house. You still have many hereditary politicians and many seats being passed down to children, particularly in the LDP.

Gradually, that process has changed. The LDP doesn’t have a primary system, but essentially has a casting call process. If you’re interested in running, you put your name in, apply, and they’ll review your application. That happens with the prefectural party, which reviews applications and then works with the national party to figure out who the candidate in a constituency should be. Sometimes, if you’re a powerful enough politician, you can overrule that process or dominate it.

At times, this has actually hurt the party. It probably hurt the LDP in this election that just passed because Nikai Toshihiro — a big power broker in the party who had been secretary general — wanted his son to inherit a seat and supported his candidacy last year. This was actually against an LDP member who had been kicked out of the party for his part in the kickback scandal. Nikai’s son lost that election.

Then Nikai pushed for him to run for an upper house seat in the prefecture during this election as the LDP candidate against a candidate who was backed by the ousted LDP member Sekō, who was an Abe ally. The independent won against Nikai’s son again — a second straight election where he was unable to win.

There’s a feeling that people are fed up with hereditary politics, feeling that politics has become this family business that people can’t break into. Even a few years ago when Abe’s nephew [Kishi Nobuchiyo] ran for the seat that was vacated by Abe’s brother, Kishi Nobuo — Nobuo’s son ran in a by-election for his seat. He won, but it was closer than you would think given the prominence of the family. You had many people in exit polls saying they didn’t want hereditary politicians. In fact, the number of people in exit polls saying they didn’t want hereditary politicians was bigger than the number of people who voted for Kishi. This suggests that some people who voted for him still didn’t like the idea that this was the choice they were being given.

There’s considerable frustration at how the political system has been dominated by familiar names — that the system hasn’t been open to new blood, to new voices, to people with different perspectives. That frustration is boiling over, and it explains at least part of the problem that the LDP is having. It has explained why there’s openness to voting for different parties. There’s a real sense of a democratic deficit — that the establishment, the LDP, and it hurts not just the LDP but pretty much any established party — these parties have dominated the system, they’re not allowing new people in, they’re not listening to younger voters, they’re not listening to the downtrodden urban working class. Something has to give, and we’re seeing that pressure start to boil over right now.

Jordan Schneider: Well, maybe they’ll just need to add another ban — viral-ban or buzz-ban, the ability to go viral. Thank you, ChatGPT, for allowing me to make jokes in a language I don’t even speak.

Kishida — is there anyone else who can fix this? We have Polymarket at 65% that he’s gone by the end of 2025. Maybe contextualize that number and what it would mean if he stayed or what happens if he goes.

Tobias Harris: I’m skeptical that Ishiba is going to stay on. He gave a press conference yesterday where he said, “I acknowledge that we were dealt a defeat and it was a message from the people, and I humbly accept that. I’m grateful to the supporters who’ve turned out for us, and I apologize to the public that we have not earned your trust."

The LDP doesn’t like losing. No one likes losing, but the LDP doesn’t like losing. The LDP has throughout its history shown that it’s willing to be quite ruthless when it comes to staying in power. It has now lost two straight national elections with Ishiba as its leader and has lost control of both houses of the Diet with Ishiba as its leader.

Beyond just the electoral defeats, there are the reasons for the electoral defeats that we’ve discussed today. You have these new threats on the right who are pulling away the party’s voters. There’s a feeling that the party is closed to new voices, is not listening to young people, and is not really delivering for many voters. Ishiba is likely to bear the blame for much of that, and there are plenty of people in the LDP who would like him gone.

The problem, of course, is what then? There is not an obvious successor. They have many challenges and many things that his successor would have to do, and some of those things are somewhat conflicting. You need someone who can maybe bring back some of the voters who defected to the right. You need someone who can maybe generate some buzz around the LDP more broadly. You maybe need someone who can signal that you’ve taken generational change seriously. You need someone who can negotiate well with the opposition parties who potentially hold the balance of power in both houses of the Diet now. You also need — not to diminish this at all — someone who can sit across the table from Donald Trump and negotiate with the United States and navigate a pretty difficult international situation.

It’s hard to think of any likely contender for the LDP’s leadership who checks all or even most of those boxes. You also need someone who can really build a consensus behind their candidacy that they are the person to solve the problems that the party is facing.

At this point, if Ishiba survives, it’s most likely just because there’s no agreement on who best resolves the party’s problems and they’re better off just sticking with Ishiba. We’ve even heard in the last couple of days that some members of the LDP are suggesting maybe it’s best for the party just to go into opposition and have out the infighting that’s going to have to happen — to do it while they’re in opposition, get themselves sorted, let the opposition parties destroy themselves and mess up, and then the LDP rides back to the rescue, like in 2012.

This is a real perspective being discussed. It would be very uncharacteristic for the LDP to just willingly say, “Fine, you guys can have power.”

Jordan Schneider: That’s true of nearly all political parties.

Tobias Harris: Yes, I don’t expect that to happen. But it tells you something about the state of the LDP’s crisis that someone is even willing to talk like this — that they recognize we’re at a stalemate. We can’t really control the governing process or the legislative process, and we’re also deeply divided internally about the direction of the party.

The right wing wants to be a pure conservative ideological party. The more reformist wing of the party — Ishiba, the younger Koizumi — they want the party to be more of what I think of as almost like one-nation Toryism. We can be the party for all people. We’re not going to be narrowly sectarian. We’re the responsible governing party and no other party can fill that role. We have to be able to do that.

That conflict is essentially irreconcilable. The right wing isn’t strong enough to impose its will on the rest of the party. The reformist part of the party has the premiership, but basically can’t force the right wing to give up their vision for what the party should look like. Until you can figure out what the party should be, they’re all just stuck together in this big tent and unhappy about it.

I do understand where this idea comes from — that going into opposition could be purifying. The LDP almost needs what happened in 2009, where they lost to the DPJ. What actually ended up happening then was that many more moderate incumbents lost in 2009. Abe comes back to the leadership in 2012. Many of the candidates that ended up coming back into the Diet when he won in 2012 were newcomers to the LDP who were much more conservative, who were closer in their politics to him, and they also owed their seats to him.

They were called the “Abe children,” and that basically helped remake the party into this much more ideologically coherent force that was Abe’s instrument for governing. Subsequently, many of the Abe children have lost their seats. It’s a much more diverse party again. Essentially what you need to happen is some sort of —

Jordan Schneider: Some sort of purification rule that only the voters are going to be able to deliver, because there’s not enough party discipline or strong leadership to make that happen.

Tobias Harris: Yes, that’s right.

Jordan Schneider: Is that a function of party rules or incentives, or just not enough charisma in the building?

Tobias Harris: Some of it is the numbers — just the numbers game. There are still enough of these Abe loyalists that they can make a lot of noise and they have ways of being obstreperous and annoying and being a thorn in Ishiba’s side.

I’m a believer in this theory that came out of the study of British politics called the Rubber Band Theory of the Premiership, which was used to talk about Thatcher’s tenure. A Prime Minister’s power stretches and contracts for idiosyncratic reasons. There are the formal powers of the office, but in practice, how big is your majority? What do the opinion polls say? What issues are prominent? What’s the mood of the country? All these issues can affect how much power the prime minister has in practice.

What’s ultimately happened is that when you lose elections, you have less power. When you don’t have the public behind you, you have less power. Ishiba’s approval ratings have been underwater for almost his entire time in office. He just doesn’t have the political capital to really impose his will on the party.

The reason it took him a bunch of tries to win the leadership after a bunch of unsuccessful attempts was that he always had this reputation of being happier as a critic on the back benches than someone who was good at making friends and making allies. Repeatedly, it didn’t do him any favors when it came time to run for the leadership because he just wasn’t good at making friends.

He was a constant thorn in Abe’s side. All of the Abe loyalists hate him. They have not forgotten, because for Abe, one of the most important things about his approach to politics was loyalty. He was very loyal to the people who stuck by him and repaid loyalty with loyalty. The people who stuck with him after he resigned in 2007 — when he came back into power, they came right with him. He stuck with them and they were Team Abe.

There’s no Team Ishiba. Ishiba does not have this group of people around him who are really populating the key positions in his government and are going to stick with him. Team Abe also meant Abe had this group of people around him who helped him make decisions and ensure that those decisions were followed through. Ishiba doesn’t have that. There’s not a Team Ishiba running the show and keeping things on track.

The result has been that there’s been a lot of oxygen for the critics to run wild with. There’s been a lot of room for the bureaucracy because they’re not getting the top-down direction from Ishiba that they would need to loyally implement the Prime Minister’s agenda. The fact that Ishiba hasn’t been able to govern with a majority means that he doesn’t really have a coherent agenda he’s pursuing. He’s basically governing from week to week based on what he can get the votes for.

If his rubber band is not very elastic, it is very contracted at this point. For a party that got used to decisive leadership during the Abe years, it’s been really hard getting acclimated to the idea of a prime minister who actually can’t do very much and doesn’t have a whole lot of power and hasn’t really articulated a positive agenda.

Jordan Schneider: We centered domestic politics partially because selfishly, I just find it so fun to talk about East Asian politics where there’s this much transparency into what the hell is going on. But also, all politics is local. I imagine a lot of what is transpiring in the US-Japan and Japan-China relationships is driven by these dynamics. I don’t know, maybe I’m wrong. But Tobias, let’s close with what the current domestic political dynamics mean for Japanese foreign relations.

Tobias Harris: Domestic politics has absolutely been a factor in what we have seen between the US and Japan over the last four months or so, certainly starting on April 2nd onward. You have had a prime minister with not a lot of flexibility domestically and facing an election and being very conscious of what was at stake in that election. Now we’re on the other side of that election, and in some ways his situation is not all that much improved because he’s still the head of a minority government.

He has spent months talking about how he’s not going to make a bad deal. He’s not going to make a deal just to keep the US happy. He’s going to defend Japan’s equities in these negotiations. Getting auto tariffs reduced is a fundamental national interest. Protecting Japan from rice imports is a fundamental national interest. He hasn’t left himself with a lot of room for compromise.

It’s worth mentioning as an aside that we have actually seen a change in the politics of US-Japan relations since Trump took office. Whereas in the past, the politics of US-Japan relations were that the first duty of a Japanese prime minister is to ensure that the relationship with the United States is going well. Successful Japanese prime ministers have understood that, and unsuccessful ones have decided to poke the bear and they’ve paid the price.

The incentives are different now. There’s a lot of anger in Japan over how they’ve been treated by the Trump administration, and the fact that Japan has gotten no credit for being the largest source of FDI in the United States and being a loyal ally and actually doing a lot to increase their defense capabilities. They feel like they’ve gotten no credit for that. They feel that in 2019 when the US and Japan signed an FTA, supposedly, there was this oral promise from Trump to Abe that he wouldn’t raise automobile tariffs on Japan. There’s a feeling that that promise was broken.

Trump talks about his great friend Abe, and yet this was how he treats Japan. In fact, it did not go unnoticed that the letter he delivered about raising tariffs to 25% on August 1st actually was delivered on the third anniversary of Abe’s assassination. That did not go unremarked by Abe loyalists. There’s a lot of bitterness.

Jordan Schneider: How much do you want to bet that they were not aware of that in the White House?

Tobias Harris: Oh, they probably weren’t. Actually, they probably didn’t think about it at all. They sent the same letter verbatim to a bunch of different countries. But no, it was noticed when the letter came through.

There’s a lot of frustration. There was a poll in the Yomiuri Shimbun either late June or early July where something like only 20% said that they trust the United States going forward. That’s an extraordinary number to see in Japan. There’s anger.

We saw the tenor of politics where Ishiba actually was criticizing the United States on the campaign trail and said he’s not going to let the United States push Japan around. I don’t think he says that if it’s not a message that wouldn’t be politically useful and wouldn’t go over well. I don’t know if it ended up being a huge issue ultimately in how people voted. But it’s worth noting that public opinion in Japan on the relationship with the US has changed. In general, the public doesn’t want the government to just make a deal to get the US off Japan’s back. They want Ishiba to stand up for Japan’s national interest and to not just make a bad deal.

All of that has shaped the circumstances that Ishiba is facing now, where he has basically a week to try to avoid 25% tariffs. I don’t know if the Trump administration is going to go easy on him — here you have a prime minister who looks like he’s on the way out. Also, if Ishiba did sign on to a deal that basically betrayed the promises that he made about the kind of deal that he was going to fight for, I don’t think that helps his survival either.

Maybe he saves himself if he actually convinces the US to sign on to a more mutual reciprocal agreement. Barring that, I don’t see a way that this helps him at all.

Jordan Schneider: We have George Glass over there as ambassador right now. Looks like he was ambassador to Portugal and a bond trader for his career. It’s a different vibe from Rahm Emanuel, but we’ll see.

Any Japan-China updates you care to share, or should we leave that for another guest?

Tobias Harris: I would say that China was almost conspicuous by its absence during the campaign in a lot of ways. There might have been hand-wavy stuff about the security threat from China. But it’s interesting — if you look at Ishiba’s stump speeches, he talked a lot more about Russia. It was a standard line in his stump speeches, right near the beginning, where he talked about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he talked about North Korea joining in, and then pivoted to talking about North Korea’s missile threats, and Russia and North Korea cooperating in East Asia. Interesting that Ishiba was consistently talking more about Russia than China.

China also is a factor in what we’ve been talking about, where one of the big dividing lines between the right wing of the LDP and Ishiba and Kishida before him, as well as Ishiba’s chief cabinet secretary, Hayashi Yoshimasa, is that they’re too soft on China. That part of the party can’t be trusted because they’re too willing to make a deal.

We have seen gradual reopening of political communication between the two governments — a lot of exchanges of visits now at a high level. The Ishiba government got a ton of heat at the start of the year when there was an agreement reached on relaxing visa requirements for Chinese coming to Japan. It’s also connected to the foreign population question because there’s a lot of Chinese buying property in Japan now. Now there’s talk about putting restrictions on foreigners buying property.

When I was in Japan in March, everyone I talked to mentioned that everywhere in central Tokyo, it’s just Chinese buying things up, coming in with cash, buying things. It’s touching Japanese politics in a lot of different ways — they’re ever present, but they weren’t necessarily front and center during the campaign, per se.

Jordan Schneider: Do Japanese political parties have theme songs in general or for each campaign in particular? Like, walk-on music?

Tobias Harris: Not generally speaking. Abe’s ads always had these exciting, dramatic, movie trailer fanfare kinds of music. The party to look at is the Japanese Communist Party — they always put out songs. They actually have some real bops. You can look for those. Actually, I should send them to you. They had one for each of their policy issues. Oh my god, they had some really good ones actually. Basically every election cycle, they’ll have a playlist.

Jordan Schneider: Amazing. We’ll definitely have one of those as outro music. I’ll pick my favorite from the recent cycle. But Tobias, what is their deal?

Tobias Harris: The Japanese Communist Party. They are a pretty old, well-established Communist Party, and generally they have fielded a lot of candidates. Obviously they never win that many seats. They are like some other more established parties, though — demographic change is hitting them hard. They have an aging base.

Jordan Schneider: Sorry, what does communism mean to them?

Tobias Harris: They’re just an extreme left party. They’re anti-big business. They are very committed to defending Article Nine. They are very opposed to the remilitarization of Japan. They’re big on gender equality. In fact, one of the better songs they have from this election cycle is their gender equality song. In some ways they’re just a progressive party. In some ways it’s Cold War era leftism brought into the 21st century.

What they have had to do in recent years is try to become a more normal party, where for a long time they were like, “We are going to run candidates everywhere. We’re not going to cooperate with any other parties. We’re not interested actually in ever taking power.” They just haven’t wanted to be a normal party.

What’s happened actually in recent years is that they’ve been more willing to cooperate with the Constitutional Democratic Party. Sometimes to the Constitutional Democratic Party’s detriment because the communist brand is still toxic in some quarters. But they’re willing to play with others more than they ever have because they recognize that they now have a superannuated base and they’re not getting any younger. If they’re going to have a role in the political system, they’ve got to be a little more creative and experimental and try to find new ways of being involved.

Jordan Schneider: Do they meet with the Vietnamese and Chinese and Cubans as brothers in the international, or not really?

Tobias Harris: They have tricky relations with China. This was actually interesting. During the Cold War, the Japanese Communist Party was more Russia-oriented and the Japanese Socialist Party was more China-oriented. Actually, the Japanese Communist Party is very critical of China and Chinese militarism — very critical of China’s human rights practices. They put out statements that would be indistinguishable from some China hawks on certain issues and in certain language, which is remarkable. They’re not always what you would expect as a communist party.

Jordan Schneider: All right, I think we’ll just have to invite one of their politicians on the show. We definitely need more communists on ChinaTalk.