Xi Takes an AI Masterclass

Inside the Politburo's AI Study Session

From an anon

On April 25, observers of China’s AI scene got an important new statement of Xi Jinping’s views on AI in the form of remarks concluding a Politburo “study session” on AI led by Xi’an Jiaotong University professor Zheng Nanning. Couched in the turgid language of Partyspeak, the readout nevertheless merits close attention as one of precious few utterances direct from the General Secretary himself on AI. To read this new tea leaf, we need to understand some background on study sessions in general, and this one in particular.

What are study sessions?

Politburo study sessions, or 集体学习 (literally, “collective study”), are regular two-hour meetings of top CCP leadership devoted to learning about some topic deemed a priority by the General Secretary. Typically, most of the session is taken up by a lecture from an academic expert in the matter in question, but occasionally Politburo members themselves make presentations. The structure was originally established by Hu Jintao shortly after he was elevated to General Secretary of the CCP in 2002, and used to consolidate his power and promote his policy priorities.

These study sessions are a far cry from your undergrad TA office hours. The topics reflect key focus areas of the paramount leader, ranging from foreign policy to technology to stuff like “Opening New Frontiers in the Sinicization and Era-ification of Marxism”. The process for putting them together is extremely involved. Party functionaries choose an expert and work with them to ensure the lecture is pitch perfect for the leader’s priorities. A professor brought in to recant the gospel of historical materialism for the group in 2013 said it took over three months to prepare for his session. There can be as many as three dress rehearsals. Study sessions typically serve to solidify and broadcast the leader’s views on some developing policy topic, not to workshop or introduce new policy. However, they do sometimes signal further action coming down the pike — occasionally to dramatic effect. A 2023 July study session on “governance of military affairs,” for example, preceded a wave of PLA purges including the ouster of 9 generals in December 2023, and more in 2024. Leader’s comments in readouts are sometimes referenced in later policies, as with “guiding opinions” on blockchain from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology in 2021 that quoted a 2019 study session.

Why study AI now?

With plenty of other signs of attention to AI coming out of Beijing these days, it’s not surprising that Xi would want to get everyone on exactly the same page on this notoriously complex topic. The last time the Politburo had a study session on AI was in 2018, led by Peking University Professor and Chinese Academy of Engineering Academician Gao Wen. This study session followed the publication of China’s landmark New Generation AI Development Plan in 2017 and presumably served to clarify how that plan should be interpreted and implemented. It could be that this April’s study session was intended partly to inform the several new funding programs announced recently.

The obvious answer, of course, is Deepseek. DeepSeek’s impressive releases of late 2024 and early 2025 catapulted the previously “low-key” company to direct attention from the very top echelons of the CCP. If the process for organizing a study session was initiated in January 2025, then a few months of preparation time would land us exactly in April. (Perhaps coincidentally, last week’s study session also comes exactly 2 and a half years after the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 — almost precisely the same amount of time as between AlphaGo’s victory over Lee Sedol in November 2016 and the last Politburo study session on AI in October 2018. This gives some indication of the metabolic speed of the CCP system.)

What did Xi have to say about it?

Alas, the Politburo neither livestreams their study sessions on Zoom, nor even shares the slides after class. But we do have a summarized version of Xi’s closing comments for the session. Given the role of study sessions in communicating the leader’s views, this is at least as important as the content of the lecture itself.

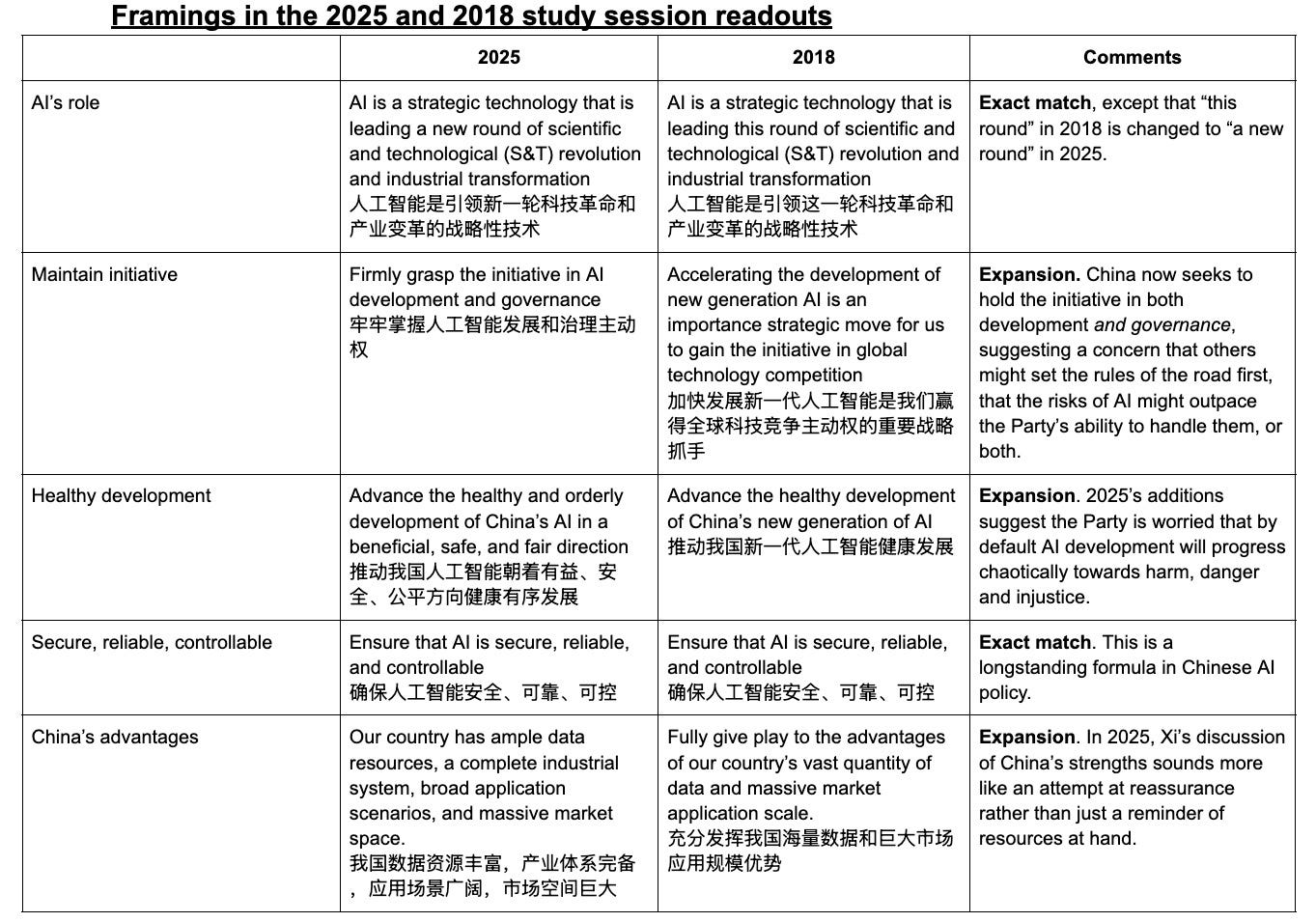

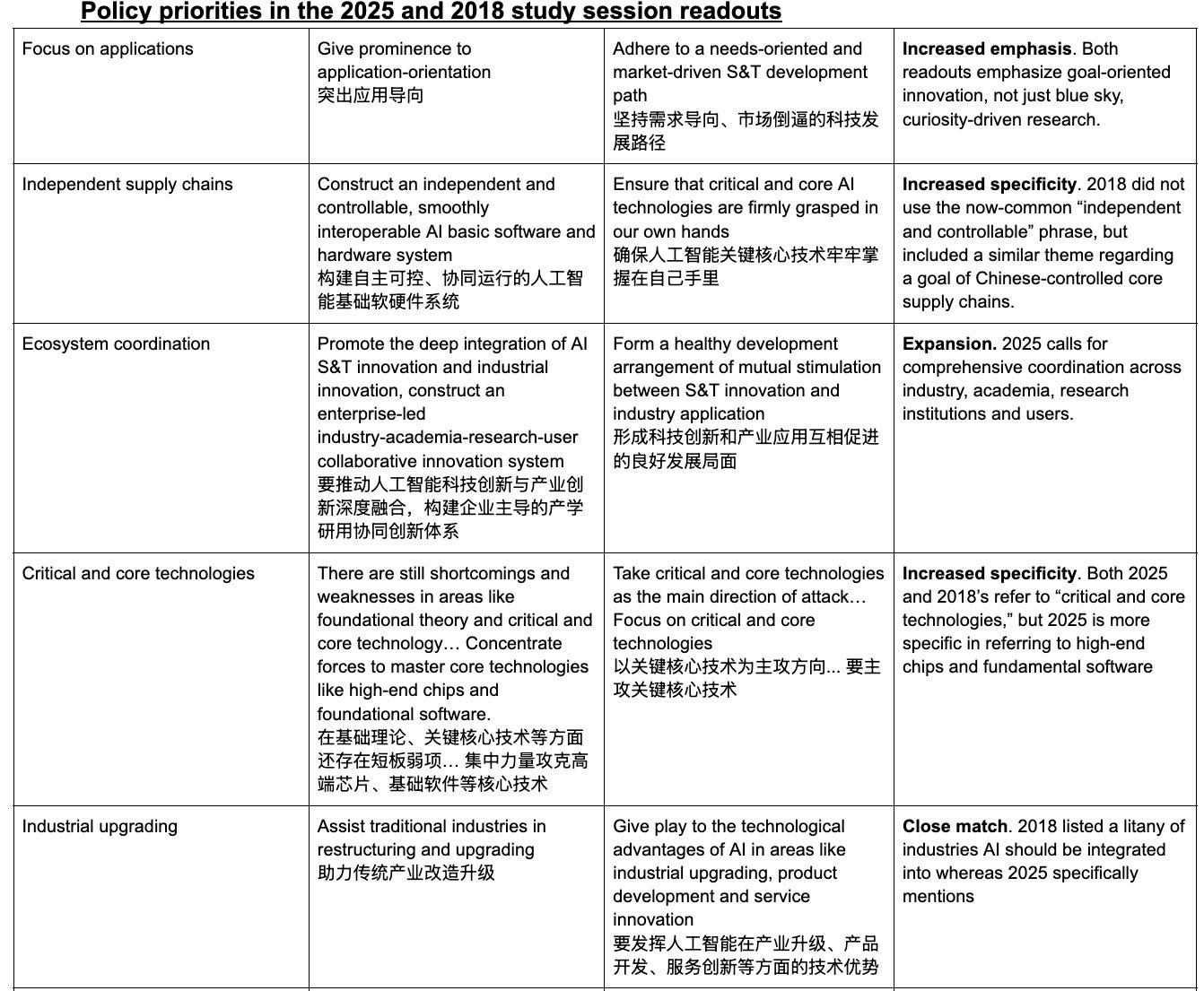

China’s approach to AI has demonstrated a lot of consistency since 2018, so Xi’s comments on this study session hit many familiar notes. The topline summary, as given in the first paragraph, is that China will use the advantages of its “whole of nation” system to persist in “self-strengthening,” with an orientation towards applications, promoting “healthy and orderly” development in a “beneficial, safe and fair” direction. Self-strengthening should especially target “core, high and foundational” technologies. Essentially, China will maintain aggressive industrial policy in an attempt to indigenize important tech supply chains, while also developing valuable applications of AI, but all subject to certain guardrails and, of course, the salubrious guidance of the Party.

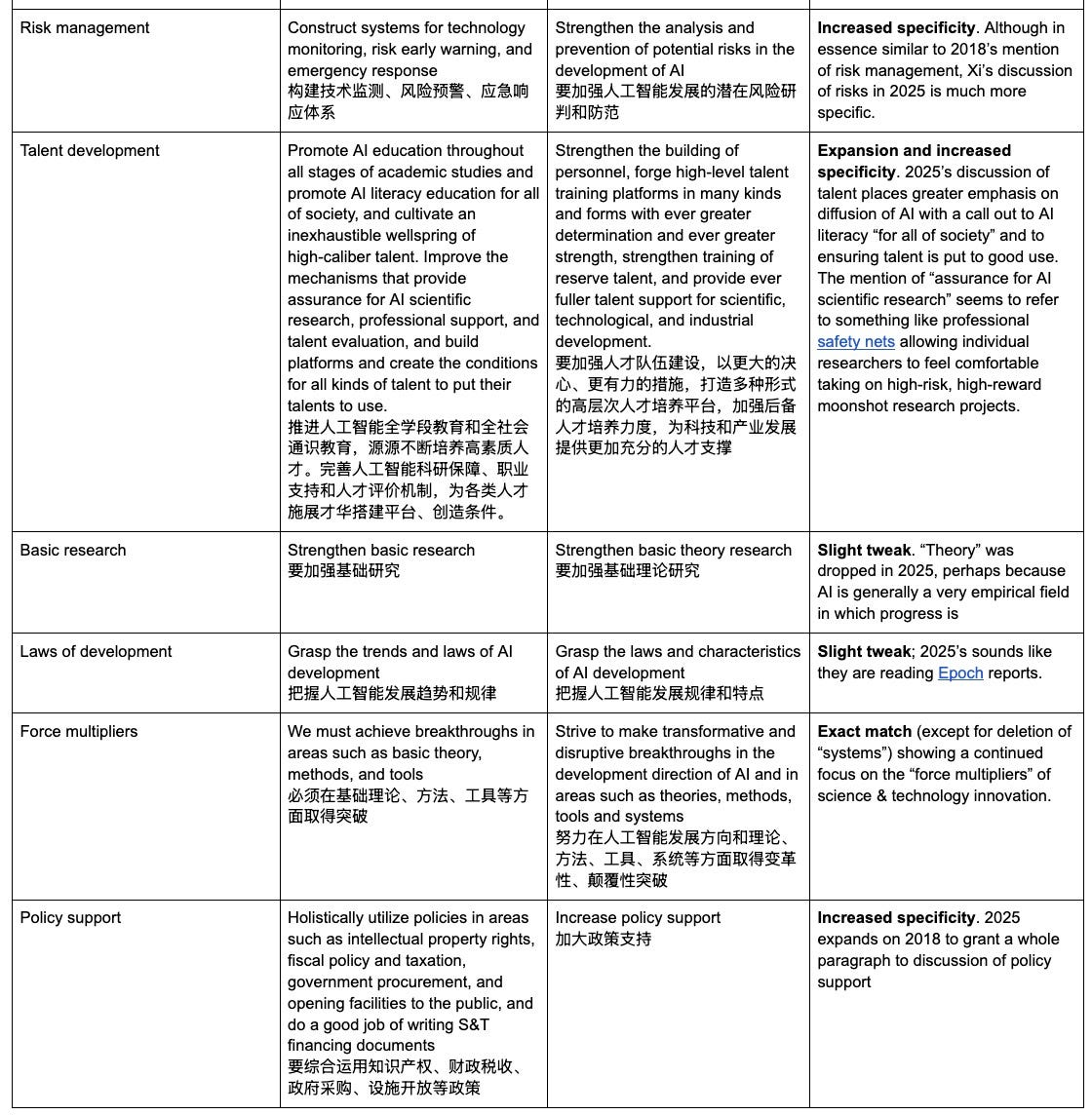

Similar themes through the two texts include concerns about China’s weakness in basic research and foundational tech but confidence about strengths in scale of data and market, a goal of properly integrating research and industry, and cultivating a thriving talent ecosystem. On many counts, however, the exact language is tweaked, often expanded or made more specific.

But some things are new! This year’s mention of “application-orientation” is similar in nature to mentions of “needs-orientation” or “problem-orientation” in 2018’s readout, but it’s now far more prominently placed, alongside “self-strengthening” in the title and in the one-sentence summary in the first paragraph. It also seems to imply more of a focus on diffusing technologies that already exist rather than creating new ones, even if “mere” engineering rather than fundamental breakthroughs, to serve national goals. This year’s readout also calls specifically for developing strategic emerging and future industries (战略性新兴产业和未来产业) and seems to give a nod to “AI for science” by referring to “a revolution in the paradigm of scientific research led by AI” (以人工智能引领科研范式变革).

As analysts have pointed out, Xi’s discussion of safety issues here is more forward-leaning than in 2018, or possibly any statement coming directly from the leader’s mouth. He describes risks from AI as “unprecedented,” and suggests implementing systems for “technology monitoring, risk early warning, and emergency response.” This is much more specific than previous policy statements calling to establish an “AI safety supervision and regulation system” or to strengthen “forward-looking (risk) prevention.” The study session readout’s language almost more closely echoes that of documents passed around at the recent Paris AI Action Summit by China’s new AISI-equivalent body, the China AI Safety and Development Association. Among a litany of priorities for the new organization, one of the more ambitious referred to setting “early warning thresholds for AI systems that may pose catastrophic or existential risks to humans.” Clearly, the thinking of safety-concerned AI experts such as famous computer scientist Andrew Yao and Tsinghua professor Xue Lan, who himself has lectured at study sessions thrice, most recently on emergency management in 2019, is finding resonance at the very top of the Party hierarchy.

A wholly novel component of the 2025 readout is the discussion of international engagement. While vague enough to be consistent with an intention to engage productively with the US and its partners’ efforts on AI governance, Xi’s focus on capacity building in the Global South and closing the “global intelligence gap” (全球智能鸿沟), as well as calling elsewhere to “grasp the initiative” in governance, suggests that this is also viewed at least partly as a dimension of international AI competition. We can imagine that Xue Lan, in particular, may have taken note of Xi’s description of AI as a potential “international public good” (国际公共产品) benefiting humanity. Xue was the lead author on a report that framed AI safety as a “global public good.” The same language later appeared in a statement from a group including Xue at the International Dialogue on AI Safety in Venice, and in a paper published by Oxford University including coauthors who work closely with Xue. Although it seems plausible that Xi’s language was influenced by this meme, there are two key differences here.

Here, Xi is referring to the benefits of AI development being a boon to the world. Though the paragraph does mention strengthening governance and creating a global governance framework, it is in the context of AI capacity-building. The most natural interpretation is that the idea here is to ensure a harmonized global regulatory regime to facilitate global diffusion and adoption of, and preempt backlash against, Chinese AI. This is distinct from the idea that AI safety is a public good, in that mitigating the downsides of AI development is beneficial to all by reducing transnational risks.

The second distinction is more subtle: Xi’s vision of AI as a public good is “international” (国际) rather than “global” (全球), notwithstanding Xinhua’s mistranslation in its English reporting on the comments. “Global” implies the whole world, taken as one single entity (especially in Chinese where the word is literally 全球 quánqíu “whole globe”). “International,” on the other hand, merely implies something that occurs between nations — and if we know one thing about nations, it’s that they don’t always treat all their fellow nations equally. In the context of a paragraph about diffusing AI technology in the Global South, a cynical read is that what this is saying is essentially: “work with China on AI, you’ll get a good deal.” In the past, the Chinese government has rhetorically promoted “open source” as a pillar of international cooperation and capacity building; here, Xi does not go so far as to use those exact words, but the fact that AI tinkerers in Indonesia can download and build on DeepSeek’s R1 may in fact be what he’s gesturing towards. The upshot here may be not so much that China hopes to save the world with, or much less from, AI, as that they are willing to cut deals with positive externalities to bind a sphere of influence together into a “community of common destiny.”

Whether in the intervening years or during their cram session, the Party has clearly learned some things about AI development.

What does this all mean for AI in China?

Although an important statement of policy, this study session may or may not indicate any significant change in policy. As discussed above, study sessions are typically less inflection points than moments of crystallization. Thus, it is most important as evidence for things we have the least evidence for otherwise.

Most striking here may be the surprising introduction of new language related to risk management. It is notable that both of the two experts to ever brief the Politburo on AI have been vocal on potential risks, with Gao Wen coauthoring a paper in 2021 on “Technical Countermeasures for Security Risks of Artificial General Intelligence” (though he is better known as the Director of the military-associated Peng Cheng Laboratory in Shenzhen). Let’s not forget either Xi Jinping’s personal letter of high praise to Andrew Yao, a key leader in the development of China’s STEM talent but also one of the key pillars on the Chinese side of the International Dialogues on AI Safety. Xi’s hand-chosen experts on AI seem more like the Yoshua Bengios and Geoffrey Hintons of the Chinese AI world than the Yann LeCuns. This would seem to bode well for the prospects of China making reasonable efforts to mitigate risks in AI development domestically, as well as via international coordination. However, besides the establishment of the China AI Safety and Development Association, a body seemingly mostly positioned currently as a talk shop to engage with the barbarians, the mention of “constructing an AI safety supervision and regulation system” in July 2024’s Third Plenum decision has yet to bear any substantive fruit. Whether they’re serious about risk mitigation will ultimately be decided by actions, not words.

For our recent debate on whether China is “racing towards AGI,” this study session is a continuation of ambiguity. Xi definitively did not signal any particular emphasis on AGI, and the focus on “application-orientation” and overall ecosystem development falsifies any kind of specific, singular technological goal for China’s AI policy. At the same time, it shows that AI is indeed a top priority for Xi. The intent to “comprehensively plan” compute resources and promote data sharing point towards the kind of national-scale mobilization of resources that would likely accompany a push for breakthroughs in general intelligence. And the Party clearly has very concrete ideas about how to compete in AI. Things are serious now.

What this study session should impress on us more than anything, however, is that top CCP leadership is not only thinking about AI, but may even be having relatively in-the-weeds shower thoughts about things like data resources, talent pipelines, and risk indicators. This attention may facilitate prudent action to avert catastrophe, but it is guaranteed to stimulate action to advance China’s long-standing goals of achieving supply chain independence and strategic technological breakthroughs. Their success will be decided by the cooperation or contention of millions of ordinary Chinese with their own hopes, fears and uncertainties for their lives in a world with AI, as well as the sharp strikes and careless fumbles of China’s geopolitical competitors, and the assistance of what partners they can muster.

But who is Zheng Nanning in any case?

Experts selected to deliver study session lectures are not so much chosen to bring something new of their own to the table as much as to bring exactly what Xi expects. So, what does the ideal avatar of Xi’s preferences for AI look like?

Zheng Nanning is an accomplished academic who takes his broader role in society seriously. His expertise lies particularly in computer vision and pattern recognition, but he has increasingly also been involved in robotics and industrial automation, promoting an idea of “intuitive intelligence” focused on enabling AIs to interact with an uncertain physical world based on semantic understanding. While we don't have the slides of the Politburo's study session, we do for a talk on “Machine Behavior and Embodied Intelligence” Zheng gave in 2023, with wide ranging discussion of machine perception, robustness, human-AI coordination and more. An academician in the Chinese Academy of Engineering, he has served as Chief Scientist in the Information Science field with the 863 Program, one of China’s longstanding key strategic technology development programs, as a member of the first Expert Advisory Committee for State Informatization, and as President of his alma mater Xi’an Jiaotong University. He has also been active in talent development efforts, leading the establishment of one of China’s first experimental undergraduate AI majors.

A profile on Zheng from last year paints him as empathetic and well-rounded: during a graduation speech in which he takes personal responsibility for the failings of super seniors and dropouts who didn’t graduate on time, he quoted from Lu Yao’s thousand-page novel Ordinary World, famous for depicting the struggles and aspirations of ordinary rural Chinese during the 1970s and 1980s. He is something of a fitness influencer, who claims to be able to do 50 pushups in one go and encourages students to set their hearts on “50 years of healthy work for the motherland.” Although it may seem cringe for your professor to try to get you to pick up a jogging habit, it instead reads as poignant in the context of a recent spate of early deaths of high-profile AI leaders in China which many attributed to the intense pressures of the field. Zheng even describes his educational philosophy as importing the “physical education spirit” into academics, saying that studies and research require the same tolerance for loneliness and constant pursuit of breakthroughs as athletics. Nor does he ignore imparting a moral formation on his pupils, stressing the importance of giving students “full and correct faith” in the CCP’s socialist core values.

Give him credit he practices what he preaches!

This personal history is a close match for much of China’s focus in AI currently: computer vision is key to the extensive surveillance apparatus of the Chinese state and a field where China leads the world technologically; “embodied intelligence,” and especially industrial robotics, is a core part of China’s bet on AI to produce “industrial upgrading” and escape the middle-income trap, called out as one of four priority “future industries” at the 2025 Two Sessions; talent development is a fundamental pillar underlying China’s goals in both basic research and diffusing AI into commercially valuable applications; and while Xi seeks to re-engineer China’s economy towards a high-end, high-tech structure, he is also attempting to re-engineer Chinese society towards cultural self-confidence, greater athleticism, and — as always — ubiquitous, intimate alignment with the Party.

There is one subtle surprise in Zheng’s profile, however. Though he attended Xi’an Jiaotong University for his bachelor’s and master’s, he did his PhD at Japan’s Keio University in the early 1980s. In recent years, foreign educational experience has flipped from a coveted asset in the Chinese professional landscape to arguably more of a liability, especially for roles with the government. In Xi’s increasingly nationalist China, a history of immersion in Western cultures suggests possible spiritual corruption. (In an overview of the study session, one Chinese blogger jokingly referred to recent comments from the chairwoman of appliance manufacturer Gree Electric that she refuses to hire such “returnees,” as there are “spies among them.”) We should not read too much into this, as education in Japan was very common for Zheng’s cohort and is generally viewed as less potentially problematic than education in the US. However, if Party planners had at all wanted to choose someone who was only educated domestically and is at least as impressive as Zheng, they probably easily could have. Under Xi, study session lecturers have increasingly come not even from academia, but from within the party-state system itself. It’s possible that, like the inclusion of an apparent foreigner in the audience at Xi’s recent visit to an AI hub in Shanghai, this weak signal of endorsement of international exchange was, though not actively sought, at least passively welcomed to communicate a marginally more open attitude to foreign and foreign-educated talent in AI. With the Trump administration giving anyone on a visa in the United States a new gray hair daily, China must certainly recognize an opportunity to win back diaspora STEM talent, and potentially even some from third countries.

Zheng also has a long history of giving comments on AI and society which appear to attune closely with Xi’s approach to AI. Already back in 2016 he was talking about the need to pursue both basic research and application-driven development as “grabbing with both hands.” He has discussed in detail the dilemma inherent in this two-pronged approach, where heavy pressure to produce scientific work can lead to researchers feeling “like ants on a hot wok” and choosing projects less ambitiously as a result. In line with Xi’s focus on attending to both safety and development, he has cautioned that AI is a double-edged sword, noting that technology has been used in the past to “stymie societal development and even cause disasters for humanity.” As a well-rounded scholar, he has pointed to the need for interdisciplinary contributions from the humanities, philosophy and law to address the risks of AI. He carves a middle path unfortunately rare also in the Western AI ecosystem in calling for scientists to neither buy into hype or spread unrealistic projects regarding AI, nor to engage in goalpost-shifting or downplaying advancements.

What does Zheng see for the future of AI? Since at least 2016 and as recently as 2021, he has described the field as facing three major challenges. The first is to make machines “learn without teachers.” Arguably, this has already been achieved by LLMs, pretrained on massive datasets via unsupervised learning and capable of impressively broad in-context learning with mere prompting. The second is to make machines perceive and understand the world like humans do. It’s unclear what exactly this would entail but it's hard to feel like we aren’t on the way there with, for instance, AI systems that can distinguish any arbitrary object in any scene. The final challenge in Zheng’s telling is to endow machines with “self-awareness, emotions and the ability to reflect on their situations and behaviors.” Hopefully, thoughtful AI researchers such as Zheng will reflect on the complex risks and philosophical questions which situational awareness and AI sentience may pose before the wrong edge of the sword cuts.

I would love to sit down with Xi and ask his genuine thoughts on AI? Does he view it as a potential threat to the Party and its hold on information? Does he view it as more of an opportunity for China? A combination of both?