Xi Zhongxun’s Second Act

Power, Purges, and the Education of Xi Jinping

This is part two of our series with Joseph Torigian, author of the definitive biography of Xi Zhongxun. This episode traces the inner world of a man navigating power politics, exile, and reform, and the legacy he left his son, Xi Jinping.

Against the backdrop of the Great Leap Forward, the Sino-Soviet split, the Cultural Revolution, and reform and opening up, we discuss…

The moral dilemmas of a mid-level party cadre,

What it’s like to be purged, and why the party prescribes self-criticism as therapy,

“Frenemies” in the CCP, Deng Xiaoping’s autocratic side, and the unsung heros of the reform period,

How Xi Zhongxun instilled party loyalty and other values in his son,

Xi Zhongxun’s return from exile and his complicated relationship with reform,

How Chinese leaders think about redemption, guilt, and survival,

And a bonus: Why the PRC-produced biopic of Xi Zhongxun is so disappointing — and why his life deserves the Star Wars treatment.

Listen on Spotify, iTunes, YouTube or your favorite podcast app.

“The Blue Flame in the Taoist Stove” 爐火純青

Jon Sine: In 1949, Xi Zhongxun is king of the Northwest. This presages three to four years in which he will be moved into a very important position in Beijing. What is particularly noteworthy about his time in the Northwest?

Joseph Torigian: Two things stand out as interesting. First is how he’s dealing with ethnic minorities. The Northwest includes Xinjiang, but also Qinghai, Gansu, and other provinces with many Hui Muslims as well as Tibetan Buddhists. This process of incorporating these regions into the regime is very bloody — it’s the crushing of an insurrection. But we see that Xi Zhongxun is simultaneously learning certain things about how to deal with ethnic minorities. He’s recognizing the value of winning over local power brokers, of not going too far too fast, of pursuing socialism in a way that’s less costly.

In fact, in 1952, he purges two leaders from Yining who pursued land reform in the nomadic areas and were suppressing at a level that Xi Zhongxun thought was inappropriate. For him, to do work in the Northwest means doing ethnic politics and the United Front. This is an important moment for him because in later years, he would spend much time on ethnic politics and he drew lessons from this period.

The other significant aspect is that in the early years of the People’s Republic of China, Mao began mass campaigns, trying to figure out how the regime could solidify, but also prevent the party from becoming divorced from the masses. During the Campaign to Suppress Counter-Revolutionaries, it’s interesting to consider whether Xi Zhongxun was pursuing an agenda that was relatively humane and how much he was listening to Mao versus working on his own. There were anti-corruption campaigns as well.

Xi Zhongxun’s absolute priority is to intuit what Mao wants and deliver it better than anyone else can. He doesn’t do perfectly, but he does a good enough job that Mao says something very striking to this man named Bo Yibo, who is the father of the notorious Bo Xilai. He says that Xi Zhongxun is like the blue flame in a Taoist stove, used to creates elixirs by the alchemists.

Mao always uses phrases that can be interpreted in many different ways, deliberately as the Sage King. Part of it was this idea that Xi Zhongxun had spent much time at the grassroots, that he had really dealt with the peasants and had been forged by them. But he also knew how much suffering Xi Zhongxun had gone through, including at the hands of his own party, and yet remained loyal to the party. This was the famous phrase that people would associate with Xi Zhongxun as Mao giving him essentially the highest, most superlative way of describing him.

It’s around that time that Xi is brought to Beijing. He’s not the only one brought to Beijing from a major bureau — another person who was brought was Deng Xiaoping. To be among what were called the five horses who entered the capital, especially because once again he was by far the youngest, makes Xi Zhongxun’s career stand out.

Mao Zedong was doing this possibly to balance against people like Zhou Enlai and Liu Shaoqi, to make sure that these guys who had spent many years in these bureaus didn’t slip out of the control of the central government. So Xi is brought to the capital and he’s made minister of propaganda. His task is to figure out how to explain to hundreds of millions of people how they’re going to build communism and why they should believe in communism, which is both an ideological thing but also a very concrete, practical thing. How exactly do you achieve literacy? What are you going to have them read? How are you going to produce what it is that they’re going to read? Are you going to work with intellectuals and inspire intellectuals, or are you going to really scare them and tell them exactly what to do? They’re struggling and figuring things out, and Xi Zhongxun’s story is part of that.

Jon Sine: You mentioned the Xinjiang purge, and the two people you’re referring to are Wang Zhen and Dong Liqun.

Joseph Torigian: Very interesting people.

Jon Sine: Very interesting. But I would like to discuss the enmities that form in this period and that linger onward. Wang Zhen, Dong Liqun, but also Deng Xiaoping, who’s leading the Southwest Bureau — this is a point at which Xi runs into problems with them that you could argue linger on for the next 30-plus years of their lives. What do you make of that?

Joseph Torigian: One of the things I tried to get across with the book was the sprawl of party history — that’s the best word for it. These people knew each other for decades and often didn’t like each other, but they still had emotional attachments to one another. All of these feelings are refracted through the party, and it’s a party that is very leader-friendly. It’s a party in which if you act as a small group, if you act as a faction, it’s extremely dangerous for you.

Certainly people have affections for each other or they have dislikes for each other or they have career ties or they happen to have similar views of a policy issue. But at the same time, even when they hate each other, they’re still frenemies in a sense because they have to work with each other. They recognize this norm of putting the party’s interests first. Even when they’re really going after each other, there are certain limitations, especially in terms of how much they can do that in concert with allies, because as soon as you start forming a small group, you’re vulnerable to the charge of factionalism.

Charisma, Coercion, and Control

Jon Sine: This is a key area in which Xi Zhongxun comes across as a nicer guy, as something of a reformer. In the Xinjiang example, he wants to use the local power brokers who are religious figures, and he doesn’t want to excessively go after them because, for the party, religion is, if not threatening, at least backward and things could get out of hand. But Xi seems to want to turn down that flame. When it comes to Tibet, Deng is leading the Southwest Bureau and it ends up having responsibility for going in there as opposed to the Northwest Bureau — if Xi might have had a slightly less...I don’t know how you would phrase that, but...

Joseph Torigian: You’re asking whether we can characterize him in particular ways with regards to ethnic politics — is he systematically different from other people in a way that’s more humane, in a way that’s more moral, in a way that’s less radical?

I could give you lots of examples where he has differences of opinions with people in the elite, where he seems to want to take a more gradual approach, a less violent approach — an approach that’s more about economic growth, addressing grievances, bringing religion into the open so that it can be controlled, and forging alliances with people who have a preexisting status within their own communities as a vector for communist power.

But we should think about that in a relative sense. These are just other tools of control. Maybe they’re more efficient tools, but ultimately his final objective is the same as everyone else, which is socialist transformation and dominance of these borderlands and placing them under the control of the Chinese Communist Party. There are lots of examples where he doesn’t come off as a soft-liner.

You talked about Xinjiang, which is a rather obvious case. But on Tibet, what’s interesting is that Xi Zhongxun has this very close relationship with the Panchen Lama. The Panchen Lamas had a falling out with the Dalai Lamas decades before, and the 10th Panchen Lama is born in Xining — he’s a young person. The party, especially Xi Zhongxun, sees the Panchen Lama as more progressive and a more natural ally to the party who can be used to pursue transformation faster.

But people like Deng Xiaoping argued that the Dalai Lama was too influential to ignore — that the Party needed to work with him, and that relying too heavily on the Panchen Lama or pushing reform too quickly in Tibet would be risky.

In 1959, the Dalai Lama flees and the people from the Northwest, like Xi Zhongxun, feel vindicated because they never trusted the Dalai Lama and preferred to empower the Panchen Lama to achieve socialist transformation more rapidly.

While Xi Zhongxun is deeply involved in ethnic politics — now in the State Council in the late 1950s — the party is literally at war with these areas that Xi Zhongxun had incorporated into the regime. It’s literally fighting a war against people in Qinghai and Gansu, and Xi Zhongxun is working with the Ethnic Affairs Commission.

He had a sensitivity. At the very least, he had an intuition for how to work with people when he wanted to, which wasn’t a very common characteristic of these guys. When he interviewed the Dalai Lama, he talked about how people often were very rude to him and they would just say things about what he was wearing and make those kinds of remarks. Whether Xi Zhongxun liked him or not, the Dalai Lama felt like he did. That was a credit to Xi Zhongxun’s ability not only to do what the party wanted, which was to win over the Dalai Lama, whatever his views might have been, but because he could be rather charming when he wanted to — which is a somewhat rare talent in the Chinese Communist Party.

Jordan Schneider: In the theme of grays, you have this quote later on where he’s like,“We need to kill people to do revolution”? That was probably during the...

Joseph Torigian: Campaign against Counter-Revolutionaries — when he uses very Stalinist language about how the bad guys are going to become more brazen because we’re doing so well, which means that they’re scared, which means that they’re going to be more dangerous. This is a way of saying that there are enemies because we’re successful, not because we’re screwing up, which means that we need to kill them and not win them over because there’s something inherently wrong with them.

Jordan Schneider: As an illustration for moral judgments — he wasn’t the one to roll the tanks into Tibet, right? That was more of a Deng-Mao thing than it was a Xi Zhongxun thing. Yes, they’re killers, but they’re killers at scale and they’re killers in a very dogmatic way. It’s more a question of whether we can do this easier or more aggressively, which is the right frame to see his actions, as opposed to projecting our own image of this man as a liberal bulwark in a revolutionary time.

Joseph Torigian: One other thing to say about the United Front is that it demonstrates an inherent dilemma. The United Front was described by Mao as one of the three treasures of the party’s toolkit. It’s essentially a way of figuring out who likes you, who’s wishy-washy about you, and who hates you. Then you empower the people who like you, you win over the people that are in the middle, and you either isolate or destroy the dead-enders. It’s a very intuitive idea — it’s what politics is all about.

But for the party it’s really hard to get right. Judging which people fall into what group is totally arbitrary and often difficult to figure out. Then, when you are winning people over, you need to listen to them, making them feel they can speak out and not get punished. It means empowering them so that their communities still have faith in them. All of those things are dangerous because those people can actually take you at your word and say things that other people don’t like, and these people also don’t like you.

You’re the party, you’ve taken over the country, you’ve conquered the nation. A lot of people think, “Why are we paying attention to these people at all? Why don’t we just kill them or throw them in jail? We’re the ones who won. Why do we have any need to accommodate these people?”

For example, in 1957, the anti-rightist campaign — it was doubly embarrassing for Xi Zhongxun because he’s working at the State Council and there are lots of people who are not members of the Chinese Communist Party working there. He’s one of the people who tells them to speak out. They do and they get punished for it. The party is mad at him for not handling these people better so they didn’t complain in the first place. These people also feel betrayed that Xi Zhongxun told them that they would be safe and then they weren’t.

In 1962, one of the accusations against Xi Zhongxun is that he was too accommodationist to the Panchen Lama and that’s why the Panchen Lama made all of these criticisms of party policy. You get this question — they returned to it in the 1980s — which is when you give space for people within the party to speak up, at what point do you co-opt them, and at what point do they take advantage of you?

In the 1980s, there was this debate. “Why are all these people protesting now? We’re being so much nicer to them than we were in the past.” In a way, it’s clueless, because people protest — that’s what they do. Perhaps you haven’t gone far enough to give them other opportunities to complain, or you haven’t done enough to make them happy.

There’s this interesting quote by Hu Yaobang where he’s just stunned at people protesting. But also he’s someone who brought this whole new model that seemed insightful and open to possibilities. This speaks to the heart of authoritarianism — when you co-opt and when you repress, how you decide and how you do it, and how you interpret certain behavior as either threatening or the system working. It’s not easy to get right, especially when there are a lot of other people in the system who don’t like you and will, when you make a mistake, not work with you to figure out a better way of doing it, but accuse you of ideological heresy of being either too left or too right. Doing the United Front is really hard.

Jordan Schneider: The question of the rate of change, both for party discipline as well and in handling restive regions, is a really interesting one. It echoes de Tocqueville’s observation that revolutions happen when you give people a little bit and then you take it away. You let up a little bit and then people are like, “Oh my God, maybe they won’t kill me if I tell them that I would actually like to pray every once in a while."

But it’s a hard thing to process if you’re as abstracted away as you are as a Hu Yaobang. Maybe your soul is a little softer and you don’t necessarily want to be burning everyone’s temples, but you want to be in control too.

Jon Sine: United Front is one of DC Policy Circle’s favorite bogeymen hiding behind potentially every organization. But reading your book is very interesting because I imagine this might be replaying nowadays — nobody actually wanted to work with the United Front. Not only because it was low status, but also because you might run the risk of being associated with people who will get you in trouble.

Joseph Torigian: The vector can go in both directions. If you tell the party, “Hey, these people are telling me stuff that makes them unhappy,” and they’re like, “Why are you telling me that they’re unhappy and not telling them to stop being unhappy?” It’s an implicit criticism of the party when you voice their criticism for them.

I thought about this a lot, which is people are really afraid of the United Front. It’s hard to do it well, you get in trouble for not doing it well, and you just don’t like doing it because it means listening to people you don’t like that much. But on the other hand, intuitively and empirically, it is nevertheless a very powerful thing.

I hope my book shows that, at the very least, even though it is something that the party has used very effectively in the past, it’s not something that’s perfect. It’s actually something that it’s easy to get wrong and that the party does get it wrong pretty regularly.

Jordan Schneider: There’s a parallel there to actually listening to the masses, because on the one hand, yes, we’re the Communist Party, of course we’re going to listen to the masses, the masses are going to lead us. Can you talk about this in the context of Xi running the remonstration bureau and the challenges that he has bringing up these complaints to the central government?

Joseph Torigian: During the Mao era, Xi Zhongxun, as a Vice Premier, was an important person but not a leading figure per se. His work on the State Council, particularly his role in managing the Petition Bureau, is interesting because of his relationship with Zhou Enlai, the State Council’s relationship with the Secretariat, and with what happens to Peng Dehuai, who is a close associate with Xi.

He’s running the petition bureau management system for the State Council, in which Chinese citizens formally had a right to go to Beijing to complain or to write messages to the party center to complain. For a party that was deeply worried about becoming divorced from the masses, you can see why in principle this is something that they should take seriously and often did, because you want to know what’s going through their heads. There were a lot of tensions in Chinese society during the 1950s, and they accelerated in dramatic ways during the Great Leap Forward.

But then you get into the politics of information control in the Leninist system, especially at a moment of crisis, and especially at a moment where you have one leader who is dominant and frightening and mercurial. One of the themes of the book is how dangerous the politics of course correction are in the Leninist system.

Xi Zhongxun knows better than most people within the elite about how bad things are going, but he has to figure out when and where to pick his battles. He also appreciates that the information he’s getting probably often is not perfect, because as he admits in a rather remarkable speech that he gives, he knows that local party officials are arresting people who are trying to complain to the top leadership.

When there’s famine everywhere and you’re trying to get a sense of how serious it is, they return to the Petition Bureau saying, “We’re not getting nearly as many complaints as we used to.” Of course, if you’re getting a lot of complaints and you’re reporting on a lot of complaints, people might say, “The Great Leap Forward is going great. Why are you taking these complaints seriously and not hunting down the people who are complaining as saboteurs who are trying to destroy this wonderful thing that’s going so well?"

He’s watching Mao who often changes his mind not because of people who are high ranking and have a lot of information showing him the evidence, but sometimes it’s his family that actually changes Mao’s mind, which is quite revealing.

Then in the 1980s — we haven’t talked about this yet — but one of the most interesting roles for Xi Zhongxun is his two stints at the National People’s Congress. This is a moment when they’re trying to figure out whether the NPC can be something more than a rubber stamp, but they’re also thinking a lot about the rule of law and how you can use the rule of law, and what the rule of law means for the party and party control.

There are debates about whether it can be used as an effective tool, but there’s tons of crime in the 1980s because the Cultural Revolution had been damaging to society and reform is in trouble if you can’t get a handle on it. They decide to do the Strike Hard campaign. Even though Xi Zhongxun says remarkable things about how seriously he takes the rule of law, he’s also still sensitive to these exigencies of the situation and allows the party to do things that have negative effects on that trajectory.

The Art of the Purge

Jon Sine: Let's turn to the Gao Gang Affair. I'm curious about your perspective, particularly through the lens of factionalism. There are different academic views on CCP factions: some, like Victor Shih, see them as more fluid ‘coalitions of the weak,’ while others view them as more durable networks. It’s quite popular now, on some websites, to categorize figures into factions based on where they worked or where they grew up. Xi Zhongxun is often placed in a ‘Northwest Faction’ alongside Gao Gang, but your evidence doesn’t lead to that conclusion. What was the Gao Gang affair actually about?

Joseph Torigian: Faction is one of these words that, like ideology, depends on which definition you’re using. If you reify this idea of faction, you have this image of cohesive blocks that work closely with one another because they happen to have had career ties — that’s very misleading. But to say that historical ties don’t matter at all would also be misleading. People are paying a lot of attention to it precisely because it’s become easy to measure those career ties. It’s valuable, but needs to be put into the context of what the party is about.

What does the party do? It makes you put the party’s interests first, and factions are a violation of that norm. Factions are one of the great taboos of party culture. It’s clumpy, but it’s not blocky, if that makes sense.

The Gao Gang affair — this is a foundational moment in Chinese Communist Party history because it’s the first great purge of the People’s Republic of China. Gao Gang and Xi Zhongxun are both Northwesterners. They have a relationship with each other. Were they acting in a factional way? Not really. In fact, Xi Zhongxun was telling Gao Gang to be careful. He wasn’t really supporting Gao Gang’s machinations and thought that Gao was acting in a dangerous way.

Then, Gao Gang goes too far. Xi Zhongxun says, “I told you to be careful, you didn’t listen to me.” When Gao goes down, Xi Zhongxun is very upset, but nevertheless, he goes along with the party’s decision. He says these terrible things about Gao Gang. If they’re a faction, then why didn’t Xi Zhongxun go down along with Gao Gang? The reason for that is how far a purge goes, who’s included in the purge, how the purge is characterized is an art form that is shaped by a myriad of different considerations that are only fully understood by the top leader. In that sense, you can see that historic ties mattered, but if we take them too far, they can be very misleading.

Jon Sine: For people who maybe don’t remember what happened in the 1950s, Gao Gang was seeing if he could get support for displacing Liu Shaoqi as the presumed successor — if I have that right.

Joseph Torigian: What was going on was two things. First, Liu Shaoqi’s problem wasn’t that he was pursuing a different line than Mao Zedong. His problem was that he just wasn’t lining up with Mao Zedong, and Mao was really unhappy about this. He starts complaining to people like Gao Gang about Liu Shaoqi and Gao is motivated by his own historical antagonisms and his own distaste for Liu Shaoqi. But Gao goes too far. He whispers to the wrong people and they go to Mao and they say, “Mao, we’re worried about this. We think it’s going to split the party.” Mao then decides to give up on Gao Gang.

He’s accused of ridiculous things. The attacks on him are so vociferous that Xi Zhongxun is frightened and surprised. In fact, he says, “I’ve never seen the premier like this. I’ve never seen Zhou Enlai like this.” The way that the purge of Gao Gang was characterized foreshadowed many other purges that would happen in subsequent years because it showed that party members were not treated like they were in a court of law. It wasn’t like they were given a serious opportunity to explain themselves. There wasn’t an objective adjudication of the evidence. Mao decided what was going to happen, everybody lined up and that was the end of that, which was a violation of the party’s own alleged norms at the time.

Jordan Schneider: Let's discuss Mao and the concept of contingency. Under Mao, under Deng and now in the Xi era, the Party has consistently operated under a model where the top leader ultimately dictates its direction, including purges and promotions, despite occasional rhetoric about collective leadership. This is the institution that Xi grew up with in this time period.

Considering the Leninist system and Mao's personal influence, what’s your interpretation of how much of this current reality is simply a downstream effect of the Leninist structure itself, versus the unique impact of ‘Mao being Mao’?

Joseph Torigian: There are different ways of thinking about this. One is that a person like Mao tends to rise to the head of an organization like the Communist Party, that people who are unlike Mao wouldn’t be able to survive as heads of the Communist Party, or that once you’re the head of a Communist Party, you become a Mao-like figure. Those are ways of thinking about counterfactuals that are important.

This question of possibility is at the very heart of the study of not just China, but the Soviet Union. In the Soviet Union, the question was, what if Bukharin had been the successor and not Stalin? Or what if Mao had died in 1950 before the party had given up on this idea of new democracy, which was putting off socialism, putting off violent transformation before Mao changed his mind, which is one of the reasons that Liu Shaoqi got caught up because he didn’t realize Mao was changing his mind so quickly in that regard? Or in the 1980s, what if Deng Xiaoping had died in ’84 or ’85 and Hu Yaobang had become the top leader?

These are really tough questions. But one thing that does emerge from the book that’s relevant for this, even though it can’t give a definitive conclusion, is that these are such leader-friendly systems that make the leader behave in particular ways that are strikingly similar, no matter who they are. This emerges in particular in the story of Deng Xiaoping, because Deng more than anybody should have understood the pathologies of the two-line system where you have a top leader and a deputy that breeds all of this distrust. He should have understood better than anybody the pathologies of succession politics.

These two are related because if the deputy isn’t doing what you want and this person might be the leader after you go, then that’s a big problem because you don’t want them to do a Khrushchev thing and de-Stalinize you after you’re dead to violate your legacy.

Here we have Deng Xiaoping, who was purged by Mao twice. This view that Deng opposes Mao or is not as radical as Mao and that he was with Liu Shaoqi or more pragmatic — it’s just not been borne out in the evidence. We have a different understanding of this interim between the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, which is a story of Mao being distant and people misreading him as opposed to really a concerted effort to undermine him.

In 1975, Deng Xiaoping is brought back after he’s purged a few years earlier and told to get the country back on its feet. He thinks he’s doing exactly what Mao wants him to do. Then people like Ye Jianying say, “Are you sure you understand what it is that Mao wants you to do?” Deng says, “Oh, he trusts me. Of course he trusts me.” Then he’s purged again because he goes too far too quickly and Mao — mercurial as ever — changes his mind.

Later, Deng purges Hu Yaobang because he says that Hu is not listening to him enough, not obeying him enough. He’s incensed that Hu Yaobang agrees when Deng says that he’s going to resign. Then Zhao Ziyang gets purged, although he’s not even opposing Deng during the June 4 crisis. He’s trying to figure out a way of saving Deng and protecting his authority while also not allowing a violent crackdown to happen. Then in 1992, Deng Xiaoping almost gets rid of Jiang Zemin. This idea that Chen Yun and Li Xiannian reined him in and he didn’t do it because they opposed him — that’s not been borne out in the evidence that I’ve been able to collect.

The puzzle here is quite striking, which is that these deputies never oppose the top leader. That’s clear from the evidence. The problem is that they keep misreading the top leader, and the top leader interprets it in this way that makes a mountain out of a molehill than is really necessary. Whether they know that and they’re doing it anyways or whether they really believe it, whatever the reason, it’s one of the fundamental factors that explains why elite politics in China has always been so explosive and why it’s always been such a leader-friendly system.

Jordan Schneider: The muscle memory of the purges and how these “personnel changes” are the way to stamp your vision onto the system seems like something which is baked in from the very beginning. With Deng and all the personnel moves as well as Mao and all the personnel moves — it’s just age. These guys are old and they’re making these decisions. You can just imagine a cranky person who has lived through everything and is convinced that they have all the answers. If you imagine the most decisive, self-confident, temperamental person, and then add on to that 60 years of revolutionary history.. But interestingly, the transition between going from someone who is subordinating themselves to another leader to being the leader yourself — or even Xi Zhongxun at the very end of his life, once his career was over, being like, “Look, I’m an independent person. I have views on this, and there were some mistakes that maybe not everyone else agreed with, but I thought were really dumb.” It’s a very interesting and maybe a more human way to relate to these folks.

Joseph Torigian: One other thing to say about this too is the Mao of the 1940s and much of the 1950s was very different from the Mao that later emerged. Fred Teiwes writes about this very eloquently, which is part of it was the story of hubris. As you said, for Mao, think of what he had accomplished, the legacy that he had forged. When things start going wrong with the Great Leap Forward and then the Cultural Revolution — even for Mao these are clearly tragic failures. It was one of the reasons why he was so worried about his legacy and why elite politics was so explosive in so many ways.

Xi Zhongxun was always loyal to Mao, always loyal to Mao’s memory, always someone who believed that Mao was a titan of Chinese history who deserved respect. But Xi Zhongxun also was not totally incapable of reflection. When he’s talking about Mao as he’s getting rehabilitated after the Cultural Revolution, he’s talking about the Mao before the 1950s, or at least the Mao of the early 1950s. You can see how he would be loyal to someone who was able to save the revolution and actually for a very long time was known as someone who is rather pragmatic and flexible and was known as someone who would take people he had defeated and let them stay in the leadership. They were given sinecures, but they weren’t shot like they were in the Soviet Union. The Chinese took some pride in that for some time. Then the purges started getting more and more...

Jordan Schneider: They started shooting people.

Joseph Torigian: Well, even in China during the Cultural Revolution, most of the deaths were like persecution to death, not executions. For Chinese citizens, many of them were executed, but there weren’t many executions of leading Chinese party officials during the Mao era or the Deng era, really, which is very different from the Soviet experience.

Jordan Schneider: That’s interesting. Most of the senior leadership deaths were suicides?

Joseph Torigian: Or just the physical torment was overwhelming. Or you’re not given treatment. Or mentally it was not easy to experience.

Frenemies and Deng’s Culture of Fear

Jon Sine: If you have the pleasure of listening to Joseph on more than one occasion, you may notice that when he says Deng, sometimes he will put an adjective before it, which is “autocratic” — “autocratic Deng” — which is part of a project of reevaluating Deng because he’s been so lionized. Let’s say more on the Great Leap Forward, because another forms at this time. Xi Zhongxun is again in a role that could be seen as “reformist.” He’s in the State Council run by Zhou Enlai in 1957. But then in ’58, Mao basically moves control of the economy out of the State Council to the Secretariat that Deng Xiaoping was running and Deng becomes the chief implementer of the Great Leap Forward. Can you speak on that?

Joseph Torigian: Through the 1950s and early 1960s, there are a handful of areas where Deng and Xi saw some tension between each other. This has come up already, but just to refresh for your listeners: Xi Zhongxun was head of the Northwest Bureau and Deng Xiaoping was head of the Southwest Bureau. The Panchen Lama was living in the Northwest Bureau when Xi Zhongxun was head of the Northwest Bureau and they established their relationship. Deng Xiaoping, on the other hand, was someone who was more supportive of the Dalai Lama. He thought that the party should not think that they could use the Panchen Lama as a weapon to undermine the Dalai Lama and that that would just backfire and that they needed to recognize the stature of the Dalai Lama in Tibetan society and work with him and win him over and get him to have faith in the Communist cause.

In the 1950s, you see this kind of weird dance between the two of them. This is the closest part in my book to something resembling factions, because you have these cadres from the Northwest Bureau in the Tibet Autonomous Region with Xi as their patron, and you have these cadres from the Southwest Bureau in the Tibet Autonomous Region with Deng as their patron, and they don’t get along. In fact, they hate each other. Xi and Deng support their protégés, but they’re reining them in and not letting them go too far. Xi and Deng are expressing respect for each other and trying to work with each other, even though they have these different inclinations. It’s such a delicate dance.

Then you have the Gao Gang incident. As I said earlier, Xi Zhongxun had said to Gao Gang, “These are Long Marchers. These people aren’t going to take us seriously.” Deng was a Long Marcher who played a fundamental role in the fall of Gao Gang. When Xi Zhongxun was forced to do self-criticisms and write reports about his relationship with Gao, the person who read them and went through them, and asked Xi all these questions was Deng Xiaoping.

Deng Xiaoping would say, decades later, that when Gao Gang fell, “We protected certain people and we promoted them, including Xi Zhongxun.” He’s taking credit for being good to Xi Zhongxun and helping him survive, although I’m sure for Xi Zhongxun, it wasn’t an especially pleasant experience.

There’s also another area of tension between them, which is related to the relationship between the State Council and the Secretariat. The State Council is the government apparatus, and it’s run by Zhou Enlai. The vice premiers include Chen Yun and one of the party’s economic czars, Chen Yi. Xi Zhongxun is essentially the secretary of the State Council. He runs the daily affairs. He works for Zhou Enlai. Then there’s the Secretariat, which had been created to run party affairs, and that’s run by Deng Xiaoping. His right hand man is Peng Zhen 彭真, a very interesting figure.

Deng and Zhou basically get along. They respect each other. Peng Zhen hates Zhou Enlai and Zhou Enlai hates Peng Zhen for all of these historic and personality reasons. Then Mao decides that Zhou Enlai doesn’t get it and he takes control over the economy from the State Council and gives it to the Secretariat. People think Zhou Enlai might be removed from the leadership. He’s going through this mental torment and Xi Zhongxun is witnessing it. At this time, the Great Leap Forward is run by the Secretariat where Deng and Peng are really true believers.

Then in 1962, Xi Zhongxun is purged from the leadership and it’s a collective effort against him and Deng Xiaoping eggs on one of the people who goes after Xi Zhongxun in the first place, Yan Hongyan 阎红彦, who is from the Northwest.

In the 1980s, it’s impossible to say how much they’re thinking about these antagonisms. Xi Zhongxun is certainly not happy that Deng Xiaoping doesn’t allow Gao Gang to be rehabilitated. I’m sure that grated on Xi Zhongxun. There are all these rumors that Xi Zhongxun will be the general secretary of the party, but it’s Hu Yaobang instead, even though Hu doesn’t have the level of prestige and status as Xi does. Whether Xi Zhongxun was unhappy about that, we don’t know. Deng was possibly using Xi even though he didn’t fully trust Xi.

Over the 1980s, Xi Zhongxun is increasingly unhappy with Deng’s autocratic style. He’s unhappy with how Hu Yaobang is treated, and he’s certainly unhappy with how Tiananmen Square goes down. But again, these are stories of frenemies. It’s not a story of Xi opposing Deng. It’s not them having fundamentally different views of how the party should work. It’s once again a complicated dance.

On the big picture of reform and opening, Xi and Deng were quite close. I’m sure that Xi was thrilled when Deng did the southern tour in 1992 and restarted reform. It was a complicated sense of emotions. One last coda to this: in the 1990s, Xi Zhongxun said something very interesting, which is that we shouldn’t give credit for all good things to Deng Xiaoping alone. It wasn’t just Deng.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned this in the first episode — how your book gives a sense of the sprawl of party history across time, across geographies, and across these people who have these half-century of professional relationships, of purge and counter-purge and ideological arguments and policy arguments.

The book manages to contain all of this complexity, giving you a sense of the scale and scope of these people and their relationships to the party and to their colleagues over time, how it evolves, and how weighty and pressureful one’s experience as a person and as a professional becomes over the course of these decades. No other party history book has really given you that sense, because the ones people first gravitate to are the biographies of Zhou and of Deng and of Mao. In Deng’s early years, you get a bit of this sense, but in the middle tier — or the bottom of the top, which is where Xi Zhongxun ends up landing over the course of his career — there are so many forces being pressed upon them at all times. You’re on this religious mission, there are all these trials and tribulations, you want to be a better person, and then you have these enemies who you think are screwing you over, but also screwing the people over. There are these incredible decisions that you have to make. Can you illustrate this with the Great Leap Forward as a case study in how you respond when you see really horrific things happening, while understanding that you are just an atom in this broader system?

Joseph Torigian: The Great Leap Forward is interesting because Xi had very powerful insight into what was going on throughout the country because of his relationship with the civil ministries and the petition bureau. Nevertheless, at the same time he is trying to radicalize the government apparatus, and he’s saying all these remarkably leftist and extreme things about how individualism is a virus, that even if you’re a very heavy-set person, if the tiniest bit of the virus gets into you, it will engulf you and consume you very quickly.

There’s a constant inner struggle within every human being to destroy the individualist and bourgeois elements — and one of the ways you do that is through physical labor. You go help build a dam or you’re sent to the countryside. He warns people: “You think you’re such an expert, but really you don’t know nearly as much as the peasants do.” He’s facilitating this radicalization by calling for things like big character posters, by empowering non-technical people to criticize technical people. That’s foreshadowing something that I don’t need to describe to you as historians of Chinese politics.

Later on, in private conversations in the 1980s, Xi Zhongxun would talk about how he had tried to prevent things from getting even worse. He claims to have ended the campaign to kill sparrows, one of the most famous elements of the Great Leap Forward. He claims to have tried to protect people like Li Rui by giving him a less serious political categorization. He was involved in famine relief. He was going to the countryside and he could see people putting a mound of dirt and putting seeds in it. And people would say, “Oh, that’s creating more space for more growth.” He was a peasant himself and he knew it didn’t work that way. He would talk about how there were fields where the crops were on the outer rim, and then you look past the crops and the whole field is empty.

He’s learning essentially about what a culture of fear does to the party. He talks about how people would watch him as he tried to fix things and then feel grudges toward him and wait and then come back at him. He talks about some of his experiences during the Great Leap Forward and this habit of lying, how lying is dangerous for the party. But in the speech where he’s talking about the fall of Hu Yaobang after Hu has just been defeated [in 1987] — we know Xi Zhongxun is unhappy and he knows all of these alleged crimes against Hu Yaobang are false, and he knows that this is a violation of collective leadership — but he says all of these horrible things about Hu Yaobang that we know he didn’t believe. He’s praising Deng for being a collective leader and saying Hu Yaobang was not a collective leader because he would just make these sudden decisions. It’s almost certain he doesn’t believe these things. In that same speech he’s talking about the Great Leap Forward as a dangerous moment where people were lying too much. How do you explain that? I don’t really know, but it’s interesting that he was reflecting on the Great Leap Forward at that particular moment.

Jon Sine: Xi Zhongxun, as you mentioned, has a quite large portfolio in the book, and one of them is managing, at least in part, the Soviet experts at the time. One plausible partial interpretation of the Great Leap Forward is as part of Mao’s growing disillusionment with the idea of fully implementing the Soviet model in China. How Xi Zhongxun’s role as mediator with the Soviets play into this? At this point Xi is traveling and going mostly to the former Soviet Union.

Joseph Torigian: The story of global communism is a big part of the book. The relationship between China and the Soviet Union in the ’50s and early ’60s is part of that. The reason it’s part of Xi’s life is, as you said, he was managing the Soviet expert program, and he was visiting Eastern Europe semi-regularly. He’s also part of the Great Leap Forward, which as you mentioned, is part of a reaction to Mao drawing certain conclusions about the trajectory of the October Revolution and Mao’s preoccupation with how China can do it better — that the Soviets are no longer ambitious enough, aggressive enough, and that he is going to show them there is an even better model than the one that Xi Zhongxun had helped export wholesale for much of the 1950s into the PRC.

In 1962, it’s Mao’s preoccupation with class struggle that Xi Zhongxun gets in trouble. One of the biggest reasons Mao care about class struggle is because he’s worrying about what happened in the Soviet Union. He’s concluding that the reason the Soviet Union has become bureaucratic and privileged — the reason the Soviet Union isn’t aggressively opposing American interests (he’s unhappy with what they tout as peaceful coexistence) — is because of revisionism. Revisionism is another way of saying that they’re not really communists anymore, that they’re heretics. He’s worried about this happening at home. He’s talking and thinking a lot about class struggle. That’s one of the reasons he reacted strongly to this novel in 1962 that saw Xi Zhongxun purged. One of the many crimes that Xi Zhongxun found himself facing was that he was a spy for the Soviet Union.

Jon Sine: We talked about this when we had Sergey Radchenko on. He doesn’t think there’s a real ideological divergence between them when Mao uses terms like revisionism. It seems like when Mao is saying something like revisionism, he’s talking about obsession with material interests. Some source said that he had read The New Class by Milovan Djilas. Putting material interest first, even if it’s within a planned structure, is anathema to him. He’s more concerned with a true spirit for forging a new man and a new world. What are your thoughts on that?

Joseph Torigian: I admire Sergey so much and he’s right that in many cases when we would think ideology would matter, it didn’t. There are lots of cases where competing interests explain a lot. But ideology and factions — these two concepts have something in common with each other, which is that they can mean many different things. To say that ideology explains everything or that it doesn’t explain anything at all, is not the right way of thinking about it. Ideology mattered at certain times, in certain ways, and it shouldn’t be understated or overstated. The Sino-Soviet split wasn’t primarily for ideological reasons, but ideology made it severe and difficult to repair. This stemmed from Mao's characteristic way of explaining differences as manifesting something deeper than reasonable people drawing reasonable conclusions.

Introspection with Chinese Characteristics

Jordan Schneider: How did Xi get purged?

Joseph Torigian: There was the trigger, and there was the political background. The trigger was that a woman, Li Jiantong, a sister to another Northwestern revolutionary named Liu Jingfan, is asked to write about Liu Zhidan, who is also Liu’s brother and Xi Zhongxun’s first great mentor. At first, Xi Zhongxun tells her not to. He’s very cautious. He thinks it’s a mistake. Gao Gang’s purge a few years earlier is making it hard to talk about the Northwest. Another level of sensitivity is what happened to Peng Dehuai in 1959 because Peng Dehuai had a very close relationship with the northwesterners. He wasn’t just the commander to Xi Zhongxun’s commissar on the Northwest Battlefield. When Peng Dehuai was fighting in the Korean War, Gao Gang was head of the Northeast and the guy who got him all of the materials that he needed. He was the logistical machine for Peng Dehuai. They were quite close.

Li Jiantong keeps pressuring him. She enlists all of these other Northwest revolutionaries, and they all put pressure on him, and they say, “You’re the only one who hasn’t died or been purged and we really need you to give approval to this because we really care about Liu Zhidan.” Xi Zhongxun finally accedes, but he also gives all this advice about how and why she should be careful. He’s still not really all that enthusiastic. He says, “You should talk a lot about Mao,” and he also says,“You also need to go talk Yan Hongyan."

Who is Yan Hongyan? In the 1940s, Mao was trying to pick a Northwesterner to represent them as a group that he could then ally with. He picks Gao Gang. But this other guy, Yan Hongyan hates Gao Gang. He thinks that he, Yan, has the revolutionary prestige and status that should justify him as being the leader of the Northwesterners. He’s really unhappy about this. So when Gao Gang is purged in the early 1950s, Yan is thrilled. He’s hoping that this is going to facilitate a revision of history that recognizes what he thinks is his rightful place.

When parts of this novel are published, Yan Hongyan is furious because he thinks this is moving backwards from the direction that he hoped, which was to make sure that Gao Gang is never rehabilitated and people like him get the respect that he thinks he deserved. He doesn’t believe that Li Jiantong wrote it. He thinks Xi Zhongxun wrote it. He doesn’t think that this woman could have produced such a work, so he complains. It’s not exactly clear what he thought would happen, but people within the leadership take this novel and they go to Mao and they say, “Why is this novel being written right now?”

“Right now” is a very sensitive political moment because Mao, for many reasons, is preoccupied with class struggle. Many members of the elite are using this to show Mao that they can find trouble when it rears its head and they can warn him so that it can be resolved before it becomes a bigger issue. We don’t know whether Mao actually believed that this was a kind of revisionist novel. It may have just been useful for him to talk about it in that particular way. But for whatever reason it was, it led to 16 years of persecution.

Jon Sine: 16 years is insane.

Jordan Schneider: The craziest thing is Xi Zhongxun is spending years and years and years reflecting on what it is that he did wrong in this and he’s doing all this self-criticism and “Oh, did I misinterpret something? What was my part in this error?” Then 40 years later he’s like, “No, I actually didn’t do anything wrong. These people are crazy.” But it took him a while to get there.

Joseph Torigian: It’s interesting that my book is a book of history and much of that 16 years is Xi Zhongxun doing self-criticism about his history and then when he’s fighting for rehabilitation, which actually doesn’t happen fully until several years after he returns to work — it’s these constant battles about how his life should be understood by the party. It speaks to how much these people, their entire sense of self-worth, their entire worldview is shaped by how the party characterizes them.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about that turn for a second, because going from the self-flagellation to, “Let me do everything I can to convince these people my self-flagellation was wrong and I was not a bad guy the whole time.” It’s a weird turn, right?

Joseph Torigian: You’re absolutely right. When he was actually writing the self-criticism, whether he was forcing himself to believe what he was writing because he recognized that the party is always right, or he was just doing it to get by — that’s an interesting question. We can only conjecture what was really going through his mind. My suspicion is that he really did find the charges ridiculous. He thought they were outrageous. But gradually, painfully and emotionally he forced himself to come as close to acknowledging the charges as he could because he recognized the possibility that it was his individuality that was the problem. He had this faith in the party always being right and in Mao always being right.

When he saw the party moving in another direction and he saw space for his case to be revisited, you can see him seeing it from the other perspective, which is he cares so much about there being a better evaluation that he would fight tooth and nail for it. We can only guess as to what his interiority was during this time, but ultimately you put the party’s interest first and if that means self-criticism, if that means transforming yourself, then that’s what happens.

One other thing too is you want to do a good self-criticism because you don’t want to hurt other people. If you fight it, it just makes things worse because it drags in other people and the party decides that they need to do even more to punish you, to scare you and to get you to break, essentially.

Jordan Schneider: Who was the guy who tried to kill himself, and everyone was like, “Why did you try to kill yourself? These are only words. You could have just chilled out and things would have come back around.”

Joseph Torigian: There’s this interesting hope that if the party is always right and you have faith in yourself, that even if you’ve made mistakes, even if you’ve done something terribly wrong, you can still win back the party’s trust by going far to acknowledge that the party is right, even when they’re going after you, and then to work even harder to show how good you are at your job and how devoted you are. The quote is from Xi Zhongxun to Gao Gang. There might have been this hope that even if you are going to be persecuted, even if you are going to be attacked, that doesn’t mean that you can’t do revolution anymore. It means you do revolution on a smaller scale. Or it might mean that you can’t do revolution for a while and then later on you come back.

Xi Zhongxun makes a remarkable statement in the 1980s, where apparently he says to somebody, “People come up, they go down, it’s cyclical, you can’t hold grudges. It’s just how our party works.” It’s almost like Democrats and Republicans and political parties in Western societies. There is this hope that they will get your case right because even if you were wrong and even if you failed, your heart is still clean and you can still prove it to them if you work even harder to dig yourself out of that hole.

Jordan Schneider: Psychologically, it is easier to stay in that mode than it is to question the essence of this and whether all the decisions you’ve made leading up to that moment were actually fighting for something which is bad.

Joseph Torigian: Oh yeah, 100%. You’re faced with two choices. One is to say that everything you’ve done so far is wrong, and you know that now because the party turned against you. That’s much harder, exactly as you said, than saying that you weren’t good enough for the party. You were the one who made the mistake. You were the one who allowed yourself to be shot by the sugar-coated bullets of bourgeois liberalization. This is how they thought. Even Xi Zhongxun himself kept warning people that there’s no stasis, there’s no equilibrium, there’s no point where you are invulnerable to mistakes because bourgeois elements keep creeping back in. You have to keep fighting it. The more confident you are, the more vulnerable you are. It’s an interesting way of thinking about the world.

Jordan Schneider: These leaders are the most into-therapy people that you could ever come across. All they’re trying to do is reform themselves and shape themselves and interrogate what it was about them as individuals that led them to do this deviation instead of that deviation. On the one hand, they’re trying to create themselves into these automatons, but there’s so much dialogue with their own interiority and individuality, which they’re trying to squeeze out of but can’t because they’re human beings. You’re basically stuck in this weird version of — it’s almost like he has nothing else to do for 16 years, aside from screwing in iPhones and just meditating on himself and all his mistakes and how he thought this wrong thing at this time.

Joseph Torigian: That’s what makes him interesting, is that when he comes out the other end, it’s remarkable how reflective he is, but it’s also remarkable how many limitations still confine him.

Jinping, I Am Your Father

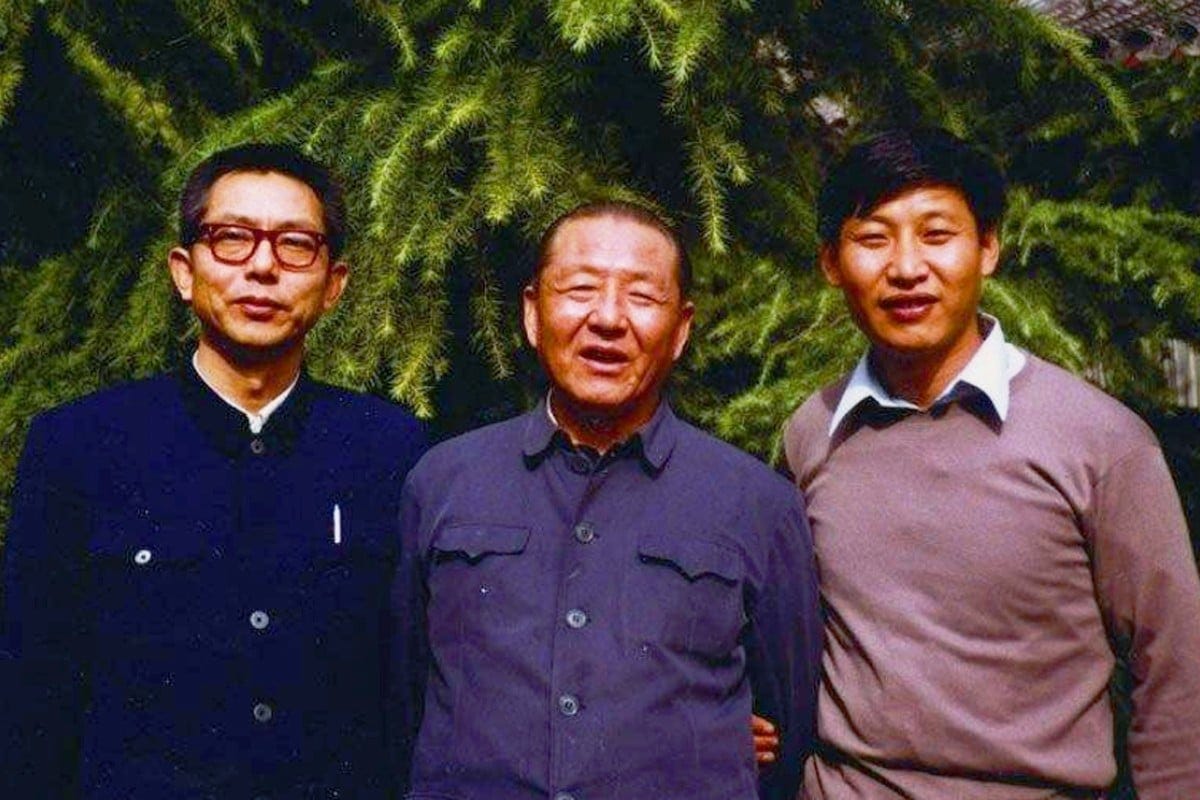

Jon Sine: This is one of the quotes that has stuck with me the most. A man named Yang Ping worked with Xi Zhongxun in a factory when he was exiled. I guess he was in Henan in Luoyang for close to a decade.

Joseph Torigian: He was there twice, both before and in the later years of the Cultural Revolution.

Jon Sine: This one is from 1976, the very late years, near the finale. At this point, Deng is being widely denounced and criticized. Yang Ping goes into Xi Zhongxun’s apartment at 8 p.m. one night:

“Yang was surprised to find Xi drinking strong cheap liquor and crying alone in the dark. Xi explained that it was his son Jinping’s birthday. Xi said, ‘Your father is better than I am; he took such good care of you. I am also a father, but because of me . . . Jinping only narrowly escaped death!’ Xi then proceeded to tell Yang about Jinping’s experiences during the Cultural Revolution. Yang later wrote, ‘That night, Old Xi spoke to me, and at the same time, he cried. He kept saying he had let down everyone in his family. He said that in terms of taking care of his entire family, his behavior had been criminal and so on. One could say that his emotional state was approaching a total lack of control. It made me feel extremely sad. Normally, his words would be very concise. He wasn’t verbose, and he didn’t repeat himself. He definitely was never incoherent.’”

At the end of this same paragraph is the thing that stuck with me the most — Xi Jinping comes to visit him a few days later. They’re both sweltering because it’s summer and they’re both sitting in their underwear smoking as Jinping recited Mao speeches from memory while Xi Zhongxun watched. At some point near the end of the book, you say that we shouldn’t necessarily think of Xi Jinping as thinking, “How could I be loyal to a party that treated my father so badly?,” but rather the inverse — “My father sacrificed so much for the party, yet still is this loyal, and still wants me to be reciting Mao speeches. How could I ever transgress that party?” In some ways, this underwear incident actually helped make that stick a little bit more for me.

Joseph Torigian: Yang Ping is struck by this. He knows Zhongxun cares about his son, he knows he feels bad about what happened to his son, and the son comes to see him on a rare visit, and what do they do? It raises questions about why this is the case.

One reason is the political background. Xi Zhongxun didn’t want his family to be a hotbed for privilege, entitlement and weakness, even though they were high ranking figures. One way of addressing that is by being tough. Xi Zhongxun had this view that if you’re not a very strict disciplinarian (and he was famous for being one), that when your children grow up, they’re not good members of society because they can’t live collectively.

But even if you are that strict and you see that strictness as a gift, as a sign of care and love, why you would have him recite Mao is an interesting question. One reason is that in 1976, Mao is still the lodestar of the communists’ sense of meaning for these people. Mao used to tell Xi Zhongxun, “You’re not reading enough. You need to read more, you need to improve your cultural side, you need to improve your ability to think ideologically.” In a way he’s doing to his son what Mao did to him, which was to tell him to read, and now he’s telling him to memorize Mao.

Xi Zhongxun is hoping is that if you’ve mastered Mao and can use Mao’s language, you can protect yourself in powerful ways. It allows you to think ideologically and not purely empirically. It allows you to be able to justify what it is that you’re doing because “I memorized Mao.” That’s a sign of political and social capital in this society. At this very same time, he’s telling other people about certain distasteful elements of the Mao era that stuck with him. Complicated person.

Jordan Schneider: It’s like a catechism, right?

Joseph Torigian: You have to memorize the ancient texts. That’s how it works.

Jon Sine: It’s kind of weird to me that Xi Jinping ends up going to Liangjiahe.

Joseph Torigian: Which happens to be Shaanxi, near where his father... I mean, the sense of historical sprawl, to use this word again, must have been palpable for him. Returning to the roots of not only communism, but of Chinese civilization, for self-revolution and for continuous re-baptism in Chinese traditional culture and revolutionary legacy.

Jon Sine: Victor Shih said in a recent podcast that the lesson that Xi Jinping likely learned from the Cultural Revolution is that what really matters is to make sure you’re on the winning side of political struggles, so that you can be the one who inflicts your will on the other side. Do you think that is a valid read? Is that interpretation in tension with the “getting redder than red” interpretation?

Joseph Torigian: That’s a false binary, frankly. I don’t think that Xi Jinping concluded when he was 15 years old that he needed to be a leader of the country so that he could protect himself and that nobody could ever hurt him. I don’t think that’s right. But I do think that he learned a lot about politics. He learned about the fickleness of human relations, the fickleness of human nature. He said that literally, in a remarkably candid moment.

How does someone who has seen the fickleness of human nature also have such a preoccupation with ideals and conviction? Stalin was the same way. Stalin was both an idealist and a realist at the same time. I don’t think that these are binaries. You need to be practical and flexible so you can achieve these idealistic goals. And you need to have faith in the final victory to motivate you to work hard and innovate and change so that you can meet the challenges as they emerge and transform.

Xi Jinping is the top leader. When he does things, we can see how it would fit the goals of a vainglorious person. I’m sure Xi Jinping has a healthy sense of personal ambition, but I don’t think he differentiates that from the party’s interests at all. He almost sees himself as an avatar for party interests. He probably almost sees himself as a person inside a machine pushing all those buttons, but the machine itself is a purposeful device that’s useful for the party to achieve its goals.

Both of those things are there at the same time. What’s good for him is good for the party. The party is an organizational weapon because it has a core. What the core does is it imposes discipline and cohesion on people who might have their own views, who might be susceptible to corruption and individualism and materialism and peaceful evolution, etc., and that he is there to stop that. That’s why he needs the power that he has brought into himself.

Jon Sine: I’m glad you call it a false dichotomy. I just spent two months of my life reading the Robert Moses biography by Robert Caro. Brilliant book. It exactly explains that this is an idealist who becomes a realist in one, but the ideals don’t necessarily match with what other people would want. The first volume of Niall Ferguson’s biography of Kissinger is titled, The Idealist. It would be quite wrong to put them as a dichotomy.

Joseph Torigian: You can be as utilitarian as you need to be precisely because you have so much conviction that the final goal deserves so much sacrifice.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about Xi’s experience during the Cultural Revolution and how his relationship to his father played into that.

Joseph Torigian: Now we’re doing this armchair Freudianism. If you want, we can put them on the couch.

Jordan Schneider: This is your time to shine.

Joseph Torigian: To be fair, Xi Jinping’s experiences during the Cultural Revolution are obviously formative. Xi Jinping, before he came to power, talked about them all the time. He talked about how when he went to the countryside, he brought these dogmatic ideas from the capital. He couldn’t get along with the peasants. He was too extreme. He ran away once because it was too hard for him. The physical labor was overwhelming. He was constantly getting bitten by bedbugs. He said that he doubted. But because he went back to it, his faith is much more unshakable than somebody who didn’t go through that process. He says that anybody who’s gone through that, nothing could make you tougher.

Now that raises an interesting question, which is, you need to go through doubt to have strong conviction. But what happens if you go through doubt and you don’t come out on the other side with strong conviction? Should you subject people to doubt? What kind of doubt is good and what kind of doubt is bad? What kind of suffering leads to dedication and what kind leads to alienation? Is it situational or is it dispositional? These are all very interesting questions to think about.

Jordan Schneider: You got this cute line in your acknowledgements. You write that this book will likely not be welcomed in the PRC at the time of publication. It’s a somewhat ironic outcome. Xi Jinping once said that his devotion to the legacy of the revolution was the result of undergoing a period of doubt when seeing the past at its worst. If the evidence shared in this book helps explain his own choices, why would the party doubt that others would not draw different conclusions about his family’s forging?

Joseph Torigian: I don’t know if you watched this TV show about Xi Zhongxun that was produced on the mainland. It was all these episodes, and I was pretty excited. I spent years of my life studying this guy, and now I get to see him on television, and I thought at the very least it would be exciting and that at least I could hear the clarion call through the show of Xi speaking to young people, and I didn’t hear it. Why? Because it didn’t have any grit, it didn’t have any sense of hazard, it didn’t have any sense of risk. It was kind of maudlin and sentimental, and there were a lot of monologues, and it was, the revolution was kind of a dinner party in a way, to turn Mao’s phrase on its head. I found that almost less inspiring than my book, where you have all the wars and everything. I can kind of get Xi Jinping a little bit when I look at the pages that I wrote, but I couldn’t get him watching this TV show. That should have been even more inspiring because you cut out all of the bad stuff.

Jon Sine: It’s what Kathleen Kennedy and Disney did to Star Wars.

Jordan Schneider: I’m going to have Tony Gilroy on to talk about Andor. He’s talked about how it was inspired by reading history and Stalin in particular as its protagonist. I’m going to pitch to him — you gotta do Xi Zhongxun next. He deserves his own Star Wars-inspired film. It’s a sad irony that the party has all this incredible material, which I think you can turn into something very inspiring from a “love the party” perspective. But the fact that they’re too scared to do that is very instructive of where we are in Xi-era China and how they view and don’t view history as an instrument.

Joseph Torigian: This is what I try to do with the book, to show that the party doesn’t just have coercive and organizational power, but that it has real emotional power. For people trying to figure out how to find meaning in their lives, Xi Jinping is telling young people to eat bitterness, telling them to go to the countryside, telling them to learn from their forebears. I’m sure that a lot of people are not going to react positively because they want to rùnxué 润学, meaning they want to learn how to live overseas, or they want to tǎngpíng 躺平, meaning they want to lie down. For Xi Jinping, those are existential problems, because if the young people aren’t on board, then that’s peaceful evolution, and you don’t want that to happen.

But his message is not totally unpersuasive for everyone. It’s human to want to be bigger than yourself and national rejuvenation is something that you would find meaningful to sacrifice for. Collective values are something that people are often attracted to emotionally. What emerges, however, from this kind of system is not just all of this excitement and meaning, but terrible suffering as well. Whatever conclusions people want to draw from that is up to them.

Jordan Schneider: That’s something that we struggle with a lot now, trying to understand the appeal that Communism had in the 1900s to the 1940s, both in the countries where revolution was happening as well as in the Western-educated world, which also found incredible inspirational power in it. Democratic socialism in America today is such weak sauce compared to what was being offered to Xi Zhongxun when he was a teenager in Shaanxi.

Joseph Torigian: There’s one way of living life, which is Netflix, dinner parties, brunch, consuming materialism, watching Andor. And there’s another where you’re a member of an organization that is leading your country to a rightful place in the world that had been lost for centuries. Choosing to support that kind of mission has repercussions, often tragic repercussions. I’m helping people understand these decisions and also helping people understand the implications of those decisions.

Return and Reform

Jon Sine: Let’s talk about how Xi Zhongxun finally comes out of the wilderness and makes it back.

Joseph Torigian: There’s this dramatic moment where Xi Zhongxun is crying again. This time he’s crying in front of a picture of Zhou Enlai who’s just died. It’s sobbing, it’s uncontrolled crying. I’ve wondered who he’s crying for, whether he’s crying for Zhou Enlai or whether he’s crying for someone else, or whether he’s crying for himself. Because the death of Zhou raises questions about what’s going to happen next. Mao is still alive. It’s unclear what the succession is going to be. There had been a brief moment when Deng had been brought back to power when it seemed like the nation was finally digging itself out of the hole in which it had found itself during the Cultural Revolution.

Mao dies, another wrenching experience again. No matter how much Xi had reflected, Mao was deeply meaningful to him in many ways. Then the Gang of Four are arrested. Mao’s initial successor is Hua Guofeng. Xi Zhongxun is rehabilitated primarily by Hua Guofeng and Wang Dongxing 汪东兴, who is in charge of the special case committees and propaganda.The decision to send Xi to Guangdong not made by Deng Xiaoping, but by Ye Jianying, who at the time was part of a triumvirate along with Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping.

It’s interesting that his first job is in Guangdong because it’s really obvious in Guangdong how bad things are, because the Gang of Four had connections there, Lin Biao had connections there, and all these killings that happened there.

It’s also right on the border with Hong Kong. Tens of thousands of people are fleeing to Hong Kong. Many of them are dying in the process. You can literally see across the street, across the river, how far behind China was.

But the case against him is not revised until 1980. He’s back to work, but on the books he’s still not fully rehabilitated, which is also kind of interesting.

Jordan Schneider: I want to stay on that moment. It must be disorienting where what you’ve devoted your life to, it’s taken 20 years out of your life and killing tens of millions of people is just losing to these colonialist capitalists, to the bourgeois people. He has to grapple with that. On the one hand, he says, “Look, we need to educate them spiritually that capitalism is bad,” but he also understands, “If we don’t step our game up, people want to eat, they want to provide for themselves and their family. Me telling them war stories about Shaanxi in the 1920s is not gonna stop folks from leaving my socialist not-so-paradise.”

Joseph Torigian: It’s another dilemma. On the one hand, you see the sources of political order and belief. On the other hand, if socialism means empty bellies, that’s dangerous. It’s a balance that’s hard to get right. You see him reflecting on it and thinking about it in real time — how you can achieve economic development without giving up on the ideology and how you can make sure people take ideology seriously even as their lives are getting better and even as you’re changing things in society that raise questions about what the heck socialism even is in the first place.

Jon Sine: The other important thing while Xi Jinping is in Guangdong, how much he’s responsible for the reforms, especially the special economic zones. He has a substantial role in the special economic zones, but initially he seems to be against the household responsibility system, which is one of the most important parts of China’s economic takeoff again in the late 70s and early 80s. Can you clarify, based on your deep research, Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping, and Xi Jinping’s respective roles to reform?

Joseph Torigian: How we think about their roles with respect to the special economic zones speaks to a lot of party historiography and how the party functions. The traditional story is that the special economic zones happened because Deng Xiaoping wanted them to happen. Xi Zhongxun played a big role too. That’s part of that story.

But actually, Deng Xiaoping wasn’t present for most of the work conference in the spring of 1979 that decided they were going to approve the special economic zones. It’s important that Deng gave his imprimatur because it was still a dangerous risk, because they could be accused of being revisionists and Trotskyites. I don’t want to discount the importance of having Deng’s approval, but it’s also very clear that Hua Guofeng was the main driver of the idea in the beginning.

We know from both memoir and archival accounts that when Xi Zhongxun went back to Guangdong, he was talking mostly about Hua Guofeng and the role that Hua Guofeng had played in this. There’s a coda to this, which is in the 1990s, Hua Guofeng tries to visit Xi Zhongxun and he’s not allowed for somewhat mysterious reasons. He’s finally granted an audience and says, “People say I’m crazy because I say that you [Xi] need to deserve credit for some of these reforms,” which is kind of a remarkable thing to say for a lot of reasons.

But the relationship between Hua Guofeng and Xi Jinping is interesting. When Xi is brought to Beijing to work on the Secretariat, he does what he’s supposed to do. He says all these horrible things about Hua Guofeng that he probably didn’t believe to signify that he was now on board with the new order that was marked by Deng Xiaoping and Hu Yaobang.

Jon Sine: It’s remarkable. People should reflect on this. You have this whole idea of the Mao-Deng transition and many people who write histories of it and make a clear delineation. Deng is the reformer and gets all the credit in the party’s details and the Western retellings of it. But here we have Hua Guofeng who is known in the West primarily for the “two whatevers,” of being Mao’s “running dog,” when there’s far more historical evidence of Deng Xiaoping serving as Mao’s right-hand man, being his “running dog,” and implementing the Great Leap Forward. The mental rejiggering this requires for some people is remarkable.

Joseph Torigian: Frankly, I don’t like talking in terms of who deserves credit for reform and opening, because there is a little bit of a historical element to it, of who did what and when. It is somewhat empirical, but it’s also such an easily weaponized and politicized debate because reform and opening is an inherently ambiguous idea and not even the Chinese could really explain it all that well. However, if not for Deng, would reform and opening look the way it did? I don’t think it would.

The bigger point here is that the through line of all these dilemmas went through Deng Xiaoping again and again. For example, the dilemma of “the three” versus “the four.” “The three” was the Third Plenum in 1978 on economic modernization. Just a few weeks later, Deng Xiaoping gives another speech where he introduces “the four” cardinal principles, which were very conservative formulations. So people were wondering, are we going to reform or not?

What’s interesting is when Xi Zhongxun saw those remarks, he was happy apparently, according to his secretary, and that Xi said, “We can’t do reform and opening right without the four cardinal principles because it sets a guideline, it sets a red line. It helps us be clear that there are certain things that aren’t going to be changed, which is very important.”

In theory this makes sense, but that in practice is hard to do at the same time. And so there are these extraordinary zigzags. We think of the Deng era as a stable era, an era of moving in one direction of economic modernization. But as I already mentioned in the previous episode, as soon as Xi Zhongxun goes to work in Beijing from Guangdong, people think another cultural revolution is happening because of a movie that people are criticizing.

Then in 1983, the campaign to eliminate spiritual pollution, people think another cultural revolution is happening. Xi Zhongxun is really unhappy with this campaign, but nevertheless he’s telling foreigners in meetings that spiritual pollution is a real problem.

The challenge of maintaining order without going too far, especially when the top leader is changing his mind and people are trying to figure out what he thinks was a formula for these really dramatic shifts throughout the entire Deng era. In some ways, Xi Jinping is a reaction to this. I don’t want to put him on the couch or anything, but Xi Jinping says, “We’re not going to be as radical as the Mao era, but we’re also going to recognize that reform and opening created real problems and we need to resolve them and I’m the one to do it.” We’re not rejecting either of these eras, but we’re going to find a happy middle. He’s saying, we’re not going to lurch back and forth. We haven’t seen quite as many really stunning things appearing under his rule as we saw during the Deng administration.

Jon Sine: Xi Zhongxun’s next spot is going back to Beijing and working under Hu Yaobang at the Secretariat. There’s a very interesting book by Julian Gewirtz, which is Never Turn Back. It’s a history of the 1980s as this possibility-hood of what could have been in terms of political reform. Hu Yaobang, there’s another good recent book, Robert Suettinger, The Conscience of the Party, Hu Yaobang. If you say reformer, Hu’s is the image that would be conjured to mind of this period. Xi Zhongxun is working under him. How does this get tied into Xi Zhongxun’’s own legacy as a reformer?

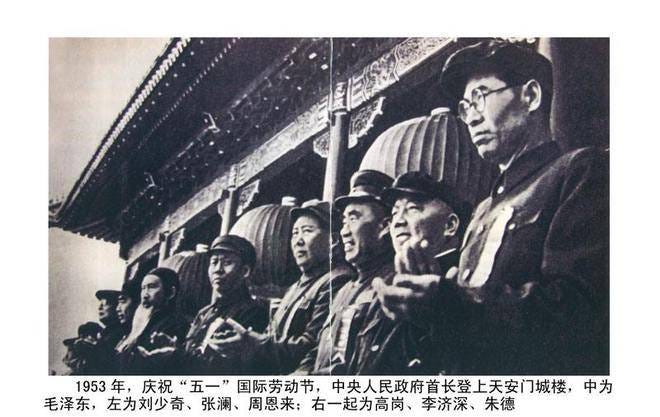

Joseph Torigian: At the Party Life Meeting that criticized Hu Yaobang, one of the individuals who was present said to Xi Zhongxun, “You went even farther than Hu Yaobang.” The question becomes, in what direction is he going even farther?