With private tutoring banned for core subjects, parents in China are looking for new ways to help their children get ahead. Today, we’ll explore the rollout of AI-enabled educational tools in China, from government initiatives encouraging teachers to adopt AI tools, to the standout startups making waves in classrooms across China.

The Need for Change

To understand the adoption of disruptive new technologies into education in China, you need to start with the recognition that there are two Chinas. There is the China that looks like this:

And then there is the majority of Chinese schools, where students won’t work on computers at all until they obtain that elusive university admissions letter and buy a laptop with their first financial aid deposit.

Chinese schooling is exam-oriented. Students spend vast amounts of time taking pen-and-paper exams in preparation for major entrance exams that determine admissions for middle school, high school, and university. While their Western counterparts’ after-school homework often involves self-driven projects, question sheets, and essays that count partially toward final grades, Chinese students usually practice past-paper questions and compilations of exam problems. This form of pedagogy does not incentivize the experimental adoption of disruptive technologies, whether in well-resourced urban schools or remote rural institutions. Of course, high-resource families recognize the importance of technology, and wealthy Chinese kids have laptops and coding classes just like their Western counterparts. But technology-driven learning largely takes a backseat compared to traditional preparations for entrance exams.

Chinese teachers rarely need to revise syllabi based on new technologies. Chinese schools award teachers bonuses based on their students’ exam performances; therefore, teachers aren’t motivated to plan activities not directly aligned with boosting exam performance. In poorer-performing schools, teachers might just “lie flat” 躺平 instead. For a more vivid illustration of the problem, take this excerpt from Peking University professor Lin Xiaoying 林小英’s well-reviewed 2023 book, Children of the County High School 《县中的孩子》:

Let us now take Provincial Demonstration High School “P High” — a school with nearly a century of history but now in decline — as an example to understand the working attitudes of teachers and their perceptions of school management. … In economically underdeveloped counties, stable high school jobs are generally considered good employment. But the infrastructure and logistics departments easily become breeding grounds for corrupt interests. At P High, encroachment by various factions has led to underfunding and outdated equipment, falling far short of national model school standards. In the eyes of students and parents, this gap is justification for demanding that teachers act not just as instructors, but also as managers, protectors, and scapegoats.

Once this cause-and-effect chain is established, teachers become increasingly distracted from teaching, channeling their energy into complaints against the school and the education bureau. This emotional drain contributes to career stagnation.

… In this environment, teachers competed not in teaching effectiveness but in laziness. Procrastination, complacency, and hedonism formed a toxic subculture among the faculty.

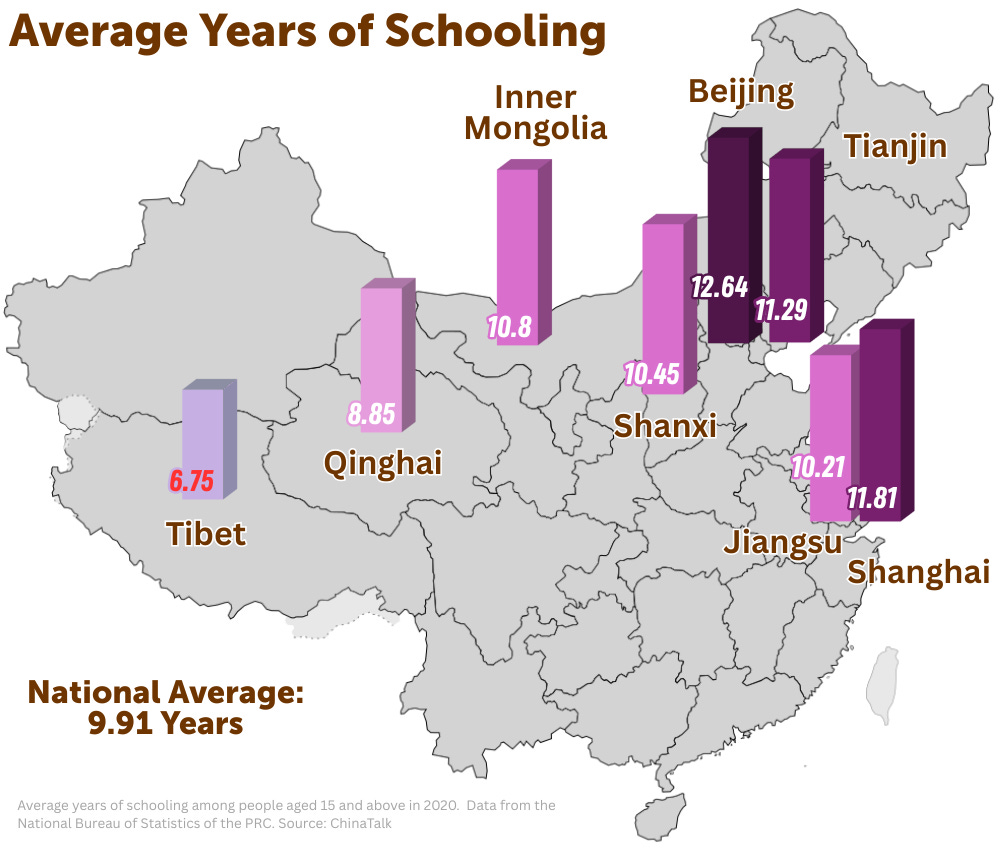

China’s education system is also highly unequal between localities. Students in Tibet spend, on average, about half as many years in school as students in Beijing:

As explained in a study by Zhang Yiwen and Liang Boren1 in 2021:

Urban schools usually have indoor gymnasiums, more formal stadiums, swimming pools, basketball courts, and other venues, while rural schools rarely have these advanced education facilities. Moreover, the rural school buildings accounted for 86% of China’s nearly 20 million square meters of dangerous school buildings. Therefore, teachers across the country will prioritize urban schools with better conditions when choosing jobs. Thus rural schools have to reduce the requirements for the recruitment of teachers, resulting in the low overall quality of teachers in rural education.

China also has fewer teachers per capita than the United States. In 2023, there was one primary school teacher in China per 16 students. For the United States in 2022 (the most recent year available), the figure is one primary school teacher per 13.26 students. (If this seems high, it’s because this number includes part-time/substitute teachers and instructors for art, music, gym, etc. This data comes from the World Bank.)

Even in primary school, Chinese class sizes are often quite large — the central government has declared that the standard primary school class size is 45 students, but there are still some regions where “large” and “super-size” (“大班” and “超大班”) classrooms of 56+ students persist.

China’s Ministry of Education is betting that technology is the key to remedying the rural-urban divide.

In April 2025, the Ministry of Education and nine other ministries released a document titled “Opinions on Accelerating Education Digitization” 关于加快推进教育数字化的意见, which argued for setting up preferential investment systems to digitize rural schools:

Establish a diversified investment mechanism. Adhere to the principle of public welfare, give play to the leading role of the government, and establish a diversified investment mechanism with the participation of the government, society, and enterprises. Ensure funding for the construction of new educational infrastructure, the purchase of high-quality digital resources and services, and give preferential support to rural and remote areas as appropriate. Basic telecommunications companies will provide preferential network usage charges for schools of all levels and types. Coordinate the use of various channels, such as market financing, to guide social capital to support the development of digital education. Schools will strengthen funding coordination to ensure digital education expenditures. Build a unified national digital education resource supply market, guide enterprises to develop digital education products and solutions that meet application needs, and protect the intellectual property rights of resource contributors.

While these recommendations don’t yet have the force of law, there are signs that the central government is preparing formal plans to integrate AI into the education system. While these moves don’t change the fundamental incentive misalignment preventing the adoption of technology-enabled tools in Chinese education institutions, they are a sign that the government is increasingly interested in digital education — and such measures could meaningfully shape demand for AI-enabled ed-tech products.

Government AI Education Directives

Long before DeepSeek mania, China’s Minister of Education Huai Jinpeng 怀进鹏 was advocating for AI educational tools. During the March 2024 National People’s Congress, he said:

In the future, we must cultivate a large number of teachers with digital literacy, strengthen the development of our teaching workforce, and deeply integrate AI technology into every aspect and stage of education, teaching, and administration. We must study its effectiveness and adaptability, so that the younger generation of students can learn more proactively, and teachers can teach more creatively.

More recently, Huai has argued for AI-enabled “smart campuses” and the need to create a national LLM for education. He also announced his intent to release a white paper on AI for education this year.

Perhaps taking the cue from Huai, the city of Beijing launched two municipal-level platforms for AI+education products — one for primary and secondary schools, and one for colleges and universities. The former is called the “AI App Supermarket” 基础教育AI应用超市, and features 23 AI products for teachers and administrators, with functions ranging from essay grading to mental-health support.

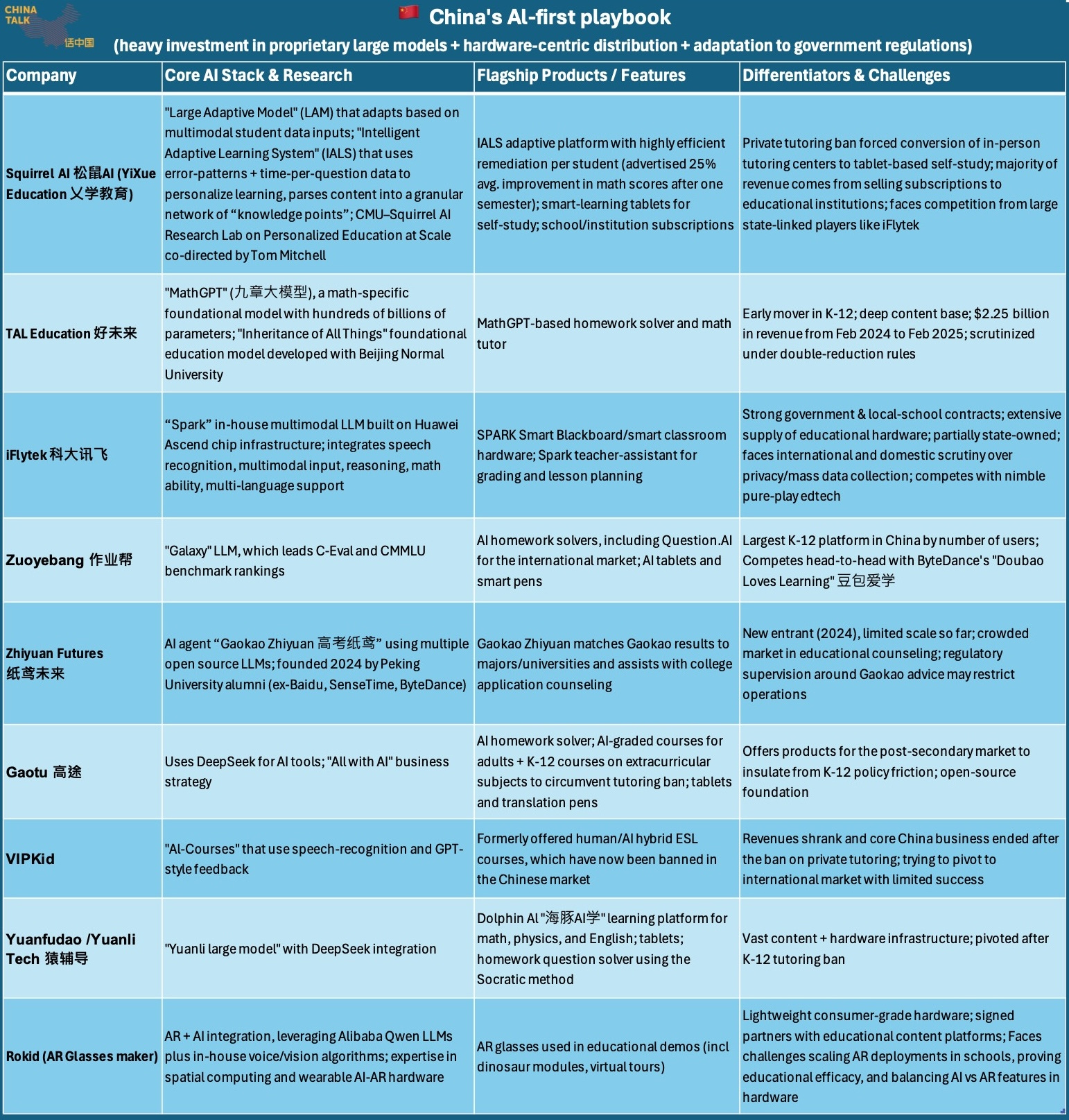

In January 2025, the CCP Central Committee and the State Council announced “China’s Education Modernization 2035” 中国教育现代化2035, a plan to build a world-class education system in China by 2035. To this end, the plan includes provisions aimed at uplifting rural schools, as well as a strategy to digitize education by “using modern technology to accelerate the reform of talent training models and achieve an organic combination of large-scale education and personalized training.” While this plan doesn’t explicitly mention artificial intelligence, Huai Jinpeng’s stance and parallel AI education initiatives at the local level could mean that AI integration will eventually be part of national education reform. If that happens, the following Chinese companies are most likely to lead the charge:

No Silver Bullets

China leads the world in popular positive AI sentiment, but the Chinese education system is still dominated by pencil and paper assignments and chalk blackboards. Meanwhile, most schools in the United States have spent the last decade issuing laptops to students, polarizing teachers and parents in the process, and perhaps fueling skepticism about using new digital technologies like AI in the classroom.

China’s push to digitize education reflects both a technological ambition and a social imperative to close the gap between rural and urban students. From smart tablets to multimodal LLMs, private companies are happy to capitalize on government initiatives like “Education Modernization 2035.” But without central government guidance on AI specifically, these new educational tools could just end up furthering inequality. While the ban on private tutoring was supposed to equalize the playing field, wealthy families largely ended up circumventing the ban by hiring one-on-one private tutors.

For AI to be a true equalizer in China’s education system, it must be paired with sustained public investment and access to digital infrastructure. Regardless of the path Beijing takes on AI, the rapid rollout of digital education tools ensures that other countries will study China’s experience going forward.

The next article in this series will cover Chinese homework-solving apps in the Chinese and American markets (looking at you, Gauth!).

You might be wondering who these people are, and that’s a fair question! This article was published in English for a conference by two Shanghai educators. I would have liked to provide a translated quote from official government research on educational inequity, but unfortunately, those reports have a lot of trouble acknowledging the problem.

Thank you for this detailed and thoughtful post. I have been working with Chinese education organizations (Beijing Normal University, Moonshot Academy, SKT Education Group, Beijing National Day School, Dandelion Education Think Tank, etc.) for more than a decade so your analysis is of great interest to me. If you would every like to discuss these topics one-on-one please let me know.