AI Slopaganda in the KMT Election

Would the generalAIssimo be proud?

Mandarin Peel is an International Relations graduate student based in Taiwan. His work focuses on U.S.–China tech competition, Indo-Pacific geopolitics, and Taiwan. You can find more of his writing on X and on Substack, where he also publishes work from fellow researchers.

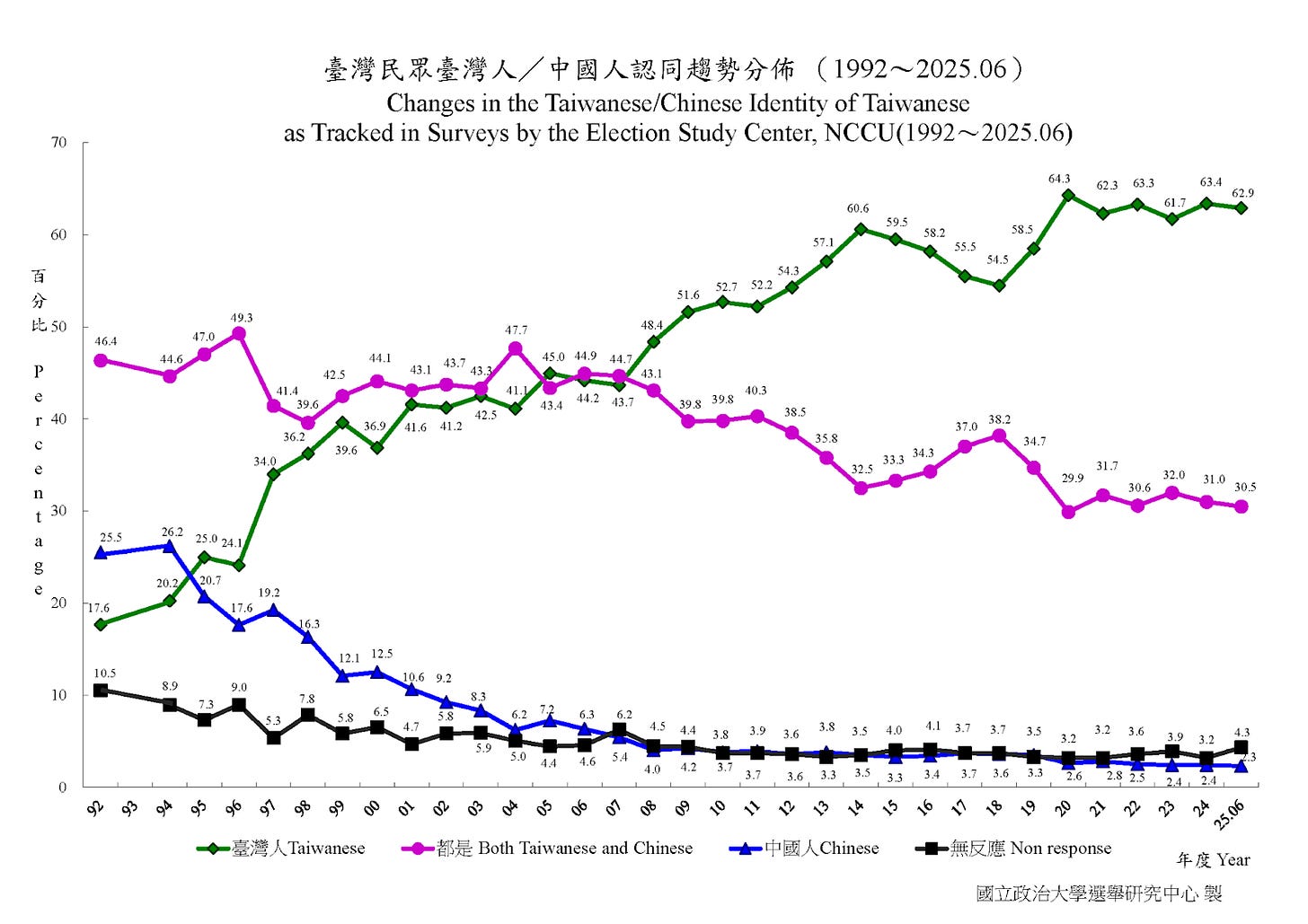

The October 2025 KMT chairmanship election came at a time of reckoning for the party. The KMT faces a difficult challenge — being the party that regards Taiwan as Chinese — trying to get elected by a public whose own identity conceptions trend the opposite way.

At first, 73-year-old Hau Lung-pin 郝龍斌, a central figure of the deep blue wing of the KMT’s old guard, was the favored candidate for the position, having built a strong network within the party over his long career. Though he has historically leaned pro-China even for the KMT, he was running to help the KMT win elections. Toward that end, his vision for the party’s new core message would step more in line with the current trends in Taiwanese identity conception: “Pro-America, not kneeling to America; Peaceful with China, not sucking up to the CCP” “親美不跪美,和中不添共.”

His main competition, and the eventual victor, was Cheng Li-wun 鄭麗文, a 55-year-old candidate with fewer connections but not without charm or vision. A brash and charismatic campaigner, she instead sought to use growing mistrust of America, brewing since the beginning of Trump’s second term, and convince voters to be unapologetically pro-China and Chinese while refusing to be a “piece in the chess game of two great powers” — a favorite metaphor of Taiwanese America-skeptics (疑美論). “This is my promise, and it’s not just elected as party chair: in the future, all Taiwanese will proudly and confidently say ‘I am Chinese.’ This is what the KMT needs to do!”

Perhaps as controversial as Cheng’s remarks was a deepfake video that emerged of Hau Lung-pin and city councilmember Liu Caiwei 柳采葳 kissing at a press conference. Hau said that posts like this were coming from “overseas” accounts seeking to influence the election. His close ally Jaw Shaw-kong 趙少康 even directly accused China of election interference. This marked a turning point as officials of the party that had previously disputed such claims are now making them too. Hau cited a National Security Bureau report that found over 1,000 videos about the election on Chinese TikTok over 20 YouTube accounts — at least half of which were posting from outside of Taiwan.

“False flag” operations, in which an actor attempts to actually convince the public that a fake event is real, are a much smaller piece of the pie, however. Jerry Yu, senior analyst at Taiwan’s Doublethink Lab, told me in an interview that the main function of AI generation for propaganda has not been to increase quality or to convince viewers that the videos are real, but to increase scale by speeding up the creation process.

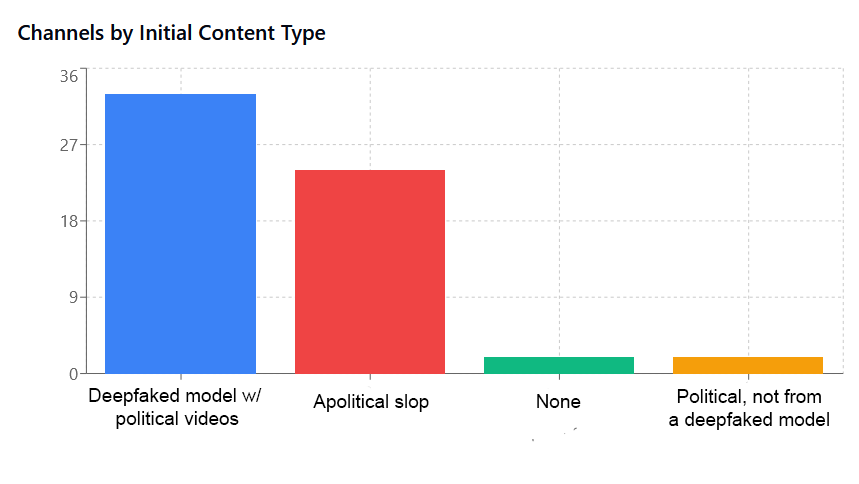

YouTube DeepFake channels

Disinformation sloperations are, however, using AI to boost their strategic sophistication, if not video quality. For example, most of the channels did not begin by posting propaganda. In the months prior to the KMT chair election, numerous accounts sprang up praising Taiwan’s natural beauty or culture. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, the channels would suddenly switch to posting pro-Cheng propaganda via DeepFakes realistic enough to fool your grandparents (and maybe even your parents). These channels exemplify the speed-over-quality strategy of AI propaganda; if the makers of these videos are trying to convince people they’re real, they’re certainly not trying that hard.

The accounts build up viewership and favor with the algorithm before eventually posting content about Taiwanese politics. One such case is 萤火 (Firefly), whose earliest available post is a full-stack AI slop story about the kind-hearted Taiwanese strangers who volunteered to help an apparently homeless American. For three months, the channel pursued its niche of faceless voiceovers retelling heartwarming stories of the Taiwanese people’s magnanimity toward foreigners. Then, after months of buttering up Taiwan, it switched to the most common model for YouTube DeepFake channels: a woman who looks like a Chinese model sitting in front of a camera and praising Cheng Li-wun and Han Guoyu 韓國瑜 at the expense of DPP politicians and the KMT old guard. Other channels — whose niches include documentaries about wild animal species, post-travel reflections on the dark sides of Japanese culture, and erotic stories about wife swapping — all switched to videos of one of several deepfaked women sharing identical political views.

Yu noted that many of these channels write their subtitles in simplified characters, which is strong evidence that the accounts come from Mainland China. The uniformity of their style is also indicates that they are part of a coordinated effort.

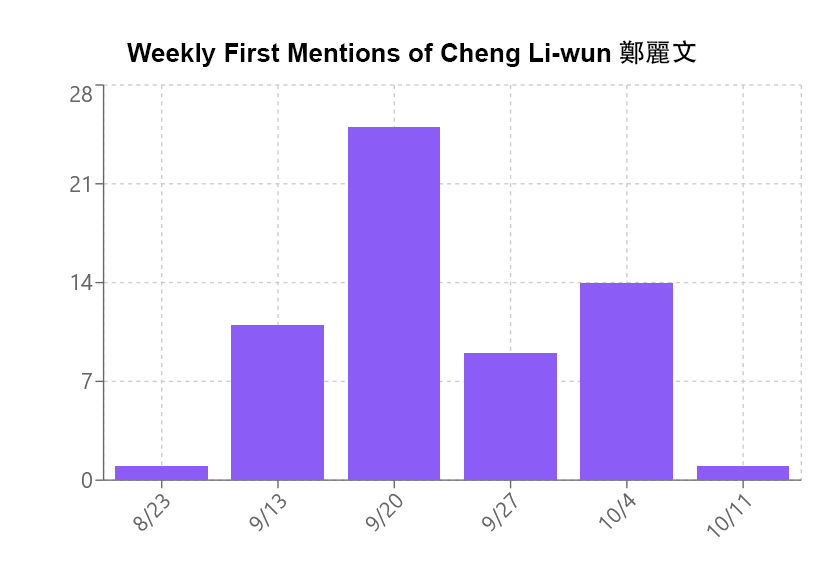

I took a look at the database of Taiwan-facing, pro-Cheng Li-wun, AI-based videos created by a partner of DoubleThink to see when these channels started cropping up, when they first began posting videos about Cheng, and where the channels have gone since.

The timing of the video proliferation gives us information as to whether the accounts were astroturfing or simply riding an existing pro-Cheng wave. At least one account with the same essential style as all of the rest released its first deepfake model Cheng Li-wun video on September 17th, the day that Cheng Li-wun announced her candidacy. Just one channel mentioned her before she announced her candidacy, arguing in late August that Cheng would be a good candidate. The new mentions of Cheng reached their peak just the week after her announcement. That they came out in droves and copied the exact format of those that had already supported her suggests strongly that this is a coordinated campaign.

Before they began posting videos of Cheng Li-wun, most would have videos from the same deepfaked character that they used to talk about Cheng Li-wun, also talking about Taiwanese domestic politics — even if they started out as political, they’d typically not start by talking about Cheng. Or, they’d switch to apolitical slop, the vast majority of which now seems to focus on Chinese entertainment industry gossip.

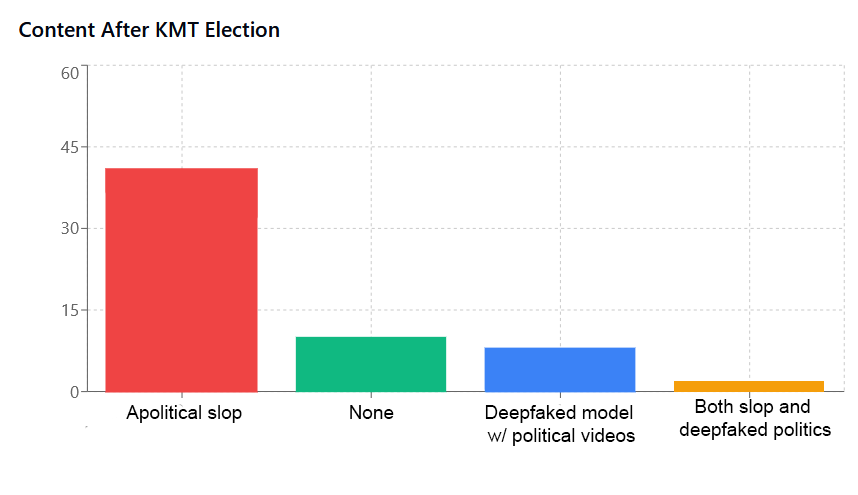

Following the election, the majority of the channels have switched to posting apolitical slop — presumably to continue growing their audiences until the next election comes around and it’s time for them to go back to politics. We have an army of accounts that were once Cheng Li-wun keyboard warriors and will almost definitely return to influence an election when needed.

Though there are no methods to definitively measure the influence of these campaigns, Yu points to how much of an underdog Cheng was when she entered the race: “She was not popular in the KMT.” He claimed that if the videos were not making a “big difference,” then Cheng Li-wun would not have won. That’s a pretty strong statement, but altogether, the evidence shows a serious and impactful operation. Some of these channels got millions of views, and they started in earnest early on during Cheng Li-wun’s campaign, when Hao Lung-pin was considered the clear favorite.

One common topic for the video is essentially “why Cheng Li-wun is the best candidate.” One video speaks about her “four trump cards” 四張王牌: (1) her grasp of the KMT’s innerworkings combined with her campaigning experience; (2) her understanding of the DPP, being a former member; (3) her ability to promote “blue-white cooperation” 藍白合作 between the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party; and (4) her tacit support from Lu Shiow-Yen 盧秀燕, the popular mayor of Taichung. Another appeared more neutral, respectfully critiquing each candidate’s debate performances while describing Cheng Li-wun as “steady, accurate, and decisive (穩,準,狠)” and saying that she showed the best prospects for attracting young people to the KMT.

On the other hand, Cheng ran an excellent campaign. Even if she was a dark horse, she had a lot going for her aside from just the campaigns — she gave strong speeches, won over important KMT figures like Ma Ying-Jeou 馬英九, and pushed a more inspiring vision for the party and won with a sizable 14.3-point margin. Her margin above a majority, however, was slim at only 0.15 percentage points.

Going above 50% of the vote has permitted pro-Cheng sources to call the election a strong mandate for Cheng to shape the party’s direction. Lu Xiaodan 陸小蛋, a Deepfake channel with nearly 1.5 million views and ~12 thousand subscribers, said: “More than half of the vote – that’s a key number. It’s not a close call; it’s overwhelming support. It represents the will of the grassroots” (超過半數的得票率,這個數字很關鍵。不是險勝,是壓倒性的支持。這代表基層的意志). That Cheng’s supporters have taken this small threshold and run with it as a mandate for change demonstrates the impact that a psyop can have, even if it only moves the result by a fraction of a percent.

TikTok

Also released in September, though having no clear connection to the KMT election, has been a remix of DPP legislator Wang Shijian 王世堅 on the Legislative Yuan’s floor slamming then-Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je 柯文哲 for his supposed failure to properly prepare the city to host the 2017 Summer Universiade. Of course, political remixes in the same vein as “Good For Nothing” 沒出息 have been around at least since Schmoyoho’s “Auto-Tune the News” — such songs have been popular for over 15 years, and voice-altering technology this good has existed since at least 2024.

But LLMs now let you make dopamine-inducing political content like never before — such as a music video where DPP legislator Wang Shijian 王世堅 impersonates Elvis and grooves out to “Good For Nothing”. The account that posted that video has posted multiple versions of the same song and also demonstrates how Sora 2 — which came out during the height of the race — may provide a leg up for election-influencing operations.

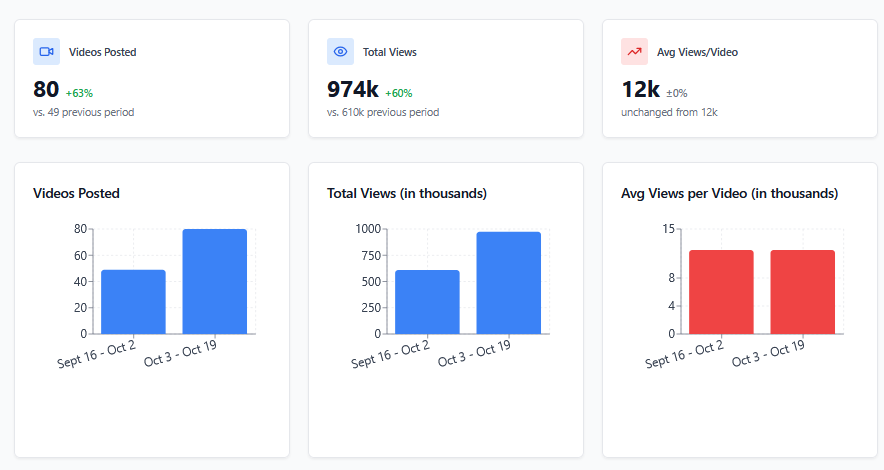

The account behind these videos, ‘gourmet.cookathome,’ seemed to switch from manual edits of the news to mostly posting AI-generated videos on October 3rd, shortly following the release of Sora 2. I compared the viewcounts from 16 days after its adoption of AI-generated videos with the equivalent period prior and found that while the average viewcount showed almost no change, the number of videos released increased by 60% — bringing the total viewcount from just over 600 thousand in the previous period to nearly one million.

As for the viral song “Good for Nothing,” Yu speculates that it at least has potential to be part of a longer-term operation. In addition to being memeable, Wang Shijian 王世堅 is known within the DPP to call out his party when he believes they have done wrong. So, if following Wang Shijian’s establishment in the Chinese and Taiwanese meme canons, we start to see a mass of Douyin and TikTok videos of Wang criticizing his own party, there will be a case that the song itself was part of a misinformation op. The video already seems to have reignited support for him, including renewed calls for him to run for mayor of Taipei City.

The Betting Website

Another piece of the AI-generated puzzle came in the form of a gambling website whose creation coincided closely with the lead-up to the election. Its X account is an apparent dummy come to life: created in January, it made a few posts about soccer and then went quiet before beginning to promote its AI-based prediction market platform in late September.

The website’s homepage was dedicated to the chair election during the final days of the race. The company is clearly run from Mainland China, with the announcement post as evidence: It specifies that Taiwan is part of China and then spells Cheng Li-wun’s name in mainland pinyin rather than the Wade-Giles romanization.

The website’s interface is pretty slick, but contains the hallmarks of being designed by an LLM: the rounded edges of the boxes, the emojis beside the text, and the text animations make it look like any standard 2025 AI startup website with a casually vibe-coded front end.

The timing of the website’s release coincides with the creation of most of the Deepfake accounts. The KMT chairmanship election was one of the first bets announced on the website, and some of the previous bets showed signs of being fake. For example, the only event under “Chess” was the “2025 World Championship”, a match that doesn’t exist (chess world championships only take place every other year). If the website was indeed vibe-coded just for this election, it’s a strong case study demonstrating the potential of the newfound ease of creating a professional-looking website for election manipulation.

Of course, it could have been a coincidence, and the fake posts of previous events exist to demonstrate their intentions to continue expanding their project, which has only just taken off. But that still begs the question: Why would a mainland Chinese prediction market startup pick a Taiwanese political party’s internal election as one of its first actual bets to run?

Professional political bettor Domer theorized on ChinaTalk about the possibility of prediction market numbers influencing a candidate’s chances to win an election: “[T]hey can say, ‘I have momentum. Here’s proof. Someone’s betting on me. My price is going up.’” What he didn’t predict was that one could accomplish the same ends by simply creating a betting website that can say, whether true or false, that a certain candidate is winning.

Conclusion

More striking than the quality or the persuasiveness of this wave of slopaganda is its rhythm. Deepfake accounts that oscillate between algorithm-friendly nothing-burgers and slews of videos from kind-of-obviously-fake beautiful women with AI-generated voices, scripts, and body motions. Innocuous remixes potentially intended as sleeper psyops making their way into your feed. An AI startup with an unusable product or a fake website with a scarily good interface. All done in broad daylight, with little attempt to hide the seams.

What a strange kind of invisibility: It’s easy to provide probabilistic evidence but impossible to provide conclusive proof. Even as those disseminating the information barely even seem to be trying to cover it up, they know that even if they’re found out, there will be no consequences, and they will still have garnered the positive feelings they needed. At least those behind the apparent campaign must have thought that their messaging would be influential, but no one can prove the sway definitively. The ambiguity feeds the machine and allows it to keep generating more of the same. Influence campaigns target social media users who keep eating the slop no matter what it’s filled with — like pigs to the slaughter.

川普就比較實際了,為何遲遲不肯關閉TIKTOK,沒有抖音,川普也別想上位。

沒有TIKTOK,就沒有異議。在串文、臉書,INSTRANT到處取消文化假正義演算法下,抖音剛好只是另一個共產主義演算法平台,提供異議機會而已。