China and Taiwan on Venezuela

"The Chinese radar's quality makes you think they bought it on Pinduoduo."

Happy New Year! ChinaTalk is kicking off 2026 with an audience survey. The link is here. Please fill it out — your feedback is important to us! ~Lily 🌸

We just dropped a Second Breakfast Venezuela emergency podcast for a breakdown of the tactical, strategic, and legal implications of abducting Maduro (listen here). ChinaTalk’s Nick Corvino below explores the China angles to this story.

Statements from the Chinese government on the US actions in Venezuela were predictably critical. China’s Foreign Ministry condemned the operation as a violation of international law and the UN Charter, called for the safety and immediate release of Maduro and his wife, and accused Washington of acting like a “world judge” and a “unilateral bully.” Beijing also backed an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council, during which they reprimanded the US on their standard grounds of sovereignty, non-interference, and opposition to hegemony.

But beyond official statements, scholars, policy analysts, and online netizens have offered a wide range of interpretations that shed light on how Chinese audiences view US power, international law, and the implications for Taiwan.

Spheres of Influence

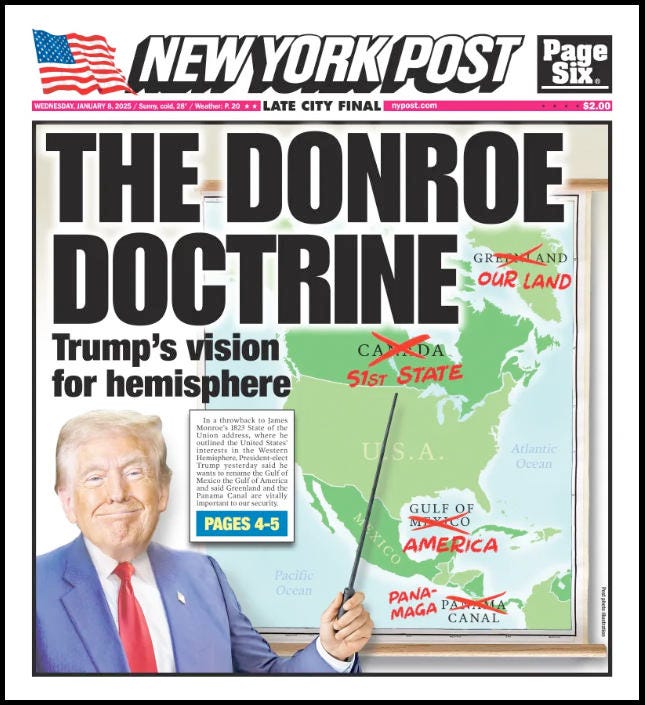

Chinese commentators have quickly embraced the neologism “唐罗主义” tángluó zhǔyì, a wordplay riff on Trump’s “Donroe Doctrine,” to frame the US move.

Niu Haibin (牛海彬), director of the Latin America research center at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, argued that while oil and sanctions matter, they are secondary: “The main objective is reflected in its new National Security Strategy, which is to rebuild US hegemony in the Western Hemisphere.”

Wang Yiwei (王义桅), the director of the International Affairs Institute at Renmin University, described the operation as evidence that the US is willing to overthrow governments it deems unfriendly to intimidate the region and reassert imperial control.

A key distinction scholars point out is that these actions violate the UN Charter and international law, which matters for Taiwan.

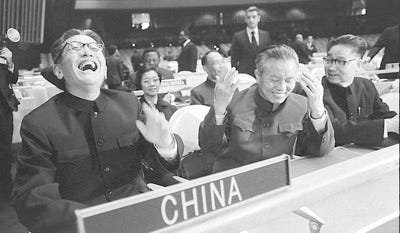

Beijing’s position rests in part on the ambiguity of UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 (1971), which recognized the People’s Republic of China as the sole legitimate representative of “China” at the United Nations and excluded the Republic of China (Taiwan) but did not explicitly resolve Taiwan’s legal status or state that Taiwan is part of the PRC. Chinese analysts invoke this ambiguity to argue that cross-strait issues fall outside the scope of international intervention, whereas US actions in Venezuela fall within that scope. Chinese scholars are therefore not arguing that the US’s actions justify carving out their own Monroe-like sphere of influence in the South China Sea or East Asia, but rather that the situations are disanalogous.

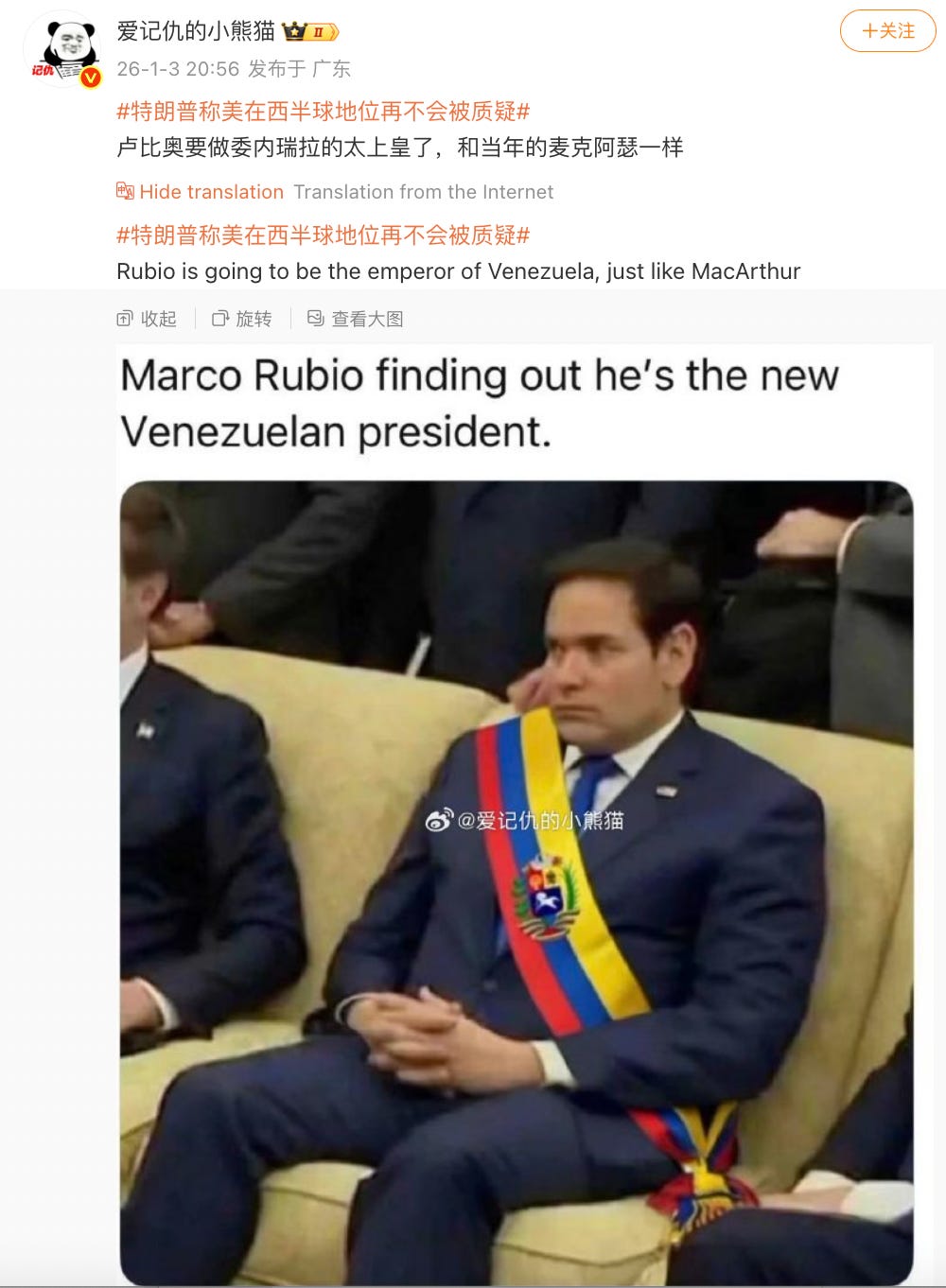

On Weibo (Chinese Twitter), some Chinese netizens have openly described the episode as a Taiwan template, arguing that it shows how quickly a great power can act, impose a fait accompli, and only afterward fight over legitimacy:

“The situation in Venezuela gives us an idea for unifying Taiwan: We could launch a special forces operation to capture Lai Ching-te, then immediately announce the takeover of Taiwan, change the identity cards the same day, and achieve a quick victory.” Source.

Others, however, pushed back against drawing a direct analogy. Some warned that equating the two cases was strategically reckless, stressing that Beijing claims far stronger legal and historical justification for Taiwan as an internal matter than the US does for intervening in Venezuela:

“Please be reminded that a US military strike against Venezuela would be a serious violation of international law and an act of aggression against a sovereign state. However, any action we take regarding Taiwan is our internal affair, and no other country has the right to interfere. These two situations are not the same, so don’t be misled by certain opinions.” Source.

For many commenters, though, the more salient takeaway was Washington reverting to a colonial or imperial mode of behavior, with netizens invoking histories of Western aggression in Asia and questioning why this intervention is treated differently from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In this telling, China’s restraint — whether in Venezuela or Ukraine — is recast as vindication rather than passivity: proof that Beijing, by staying out, avoids exposing the coercive instincts that Western powers reveal when they intervene abroad under ideological pretexts that critics say often mask more material interests, like oil.

On Taiwanese social media, the reaction has been different.

ChinaTalk Taiwan correspondent Lily Ottinger notes that much of the online discussion has focused on military performance. Bloomberg reported — later rewritten with direct quotes by Taiwan’s Central News Agency — that a senior Taiwanese national security official viewed the episode as helpful for deterrence, signaling that President Trump is willing to use force in defense of what he sees as core US interests, and that US forces can overwhelm militaries reliant on Chinese equipment.

From a PTT (Taiwan’s popular Reddit-like forum site) discussion of the comments:

“Chinese radar, Russian missiles, it’s really a joke.”

“It turns out Chinese radar is garbage; air superiority in the Taiwan Strait is basically firmly in Taiwan’s hands.”

“The quality of that Chinese radar makes one wonder if it was bought through Pinduoduo.”

Some Taiwanese legacy media went further. One article by the DPP-leaning Liberty Times (自由時報), titled “The Failure of the China Model,” argued that despite Venezuela being one of China’s closest military partners in South America — operating Chinese-made radar systems, K-8 trainer aircraft, and armored vehicles, and reportedly hosting Chinese military advisers — the operation revealed how little that partnership translated into real defensive capability. China’s “defensive shield” collapsed under pressure, and Beijing’s lack of response reinforced the perception that China is a limited security partner when confronted with US forces.

Venezuela’s Chinese-supplied radar network failed to detect or deter US aircraft and was quickly neutralized, overwhelmed by superior electronic warfare and precision strikes. But this says only so much about the quality of Chinese weapons. China has not supplied Venezuela with its most advanced systems, and many of the country’s more serious air-defense capabilities — such as surface-to-air missile systems — were sourced from Russia and poorly paintained. Seen this way, the episode could reflect less a failure of Chinese hardware than the limits Beijing has deliberately placed on how far it is willing to militarize partners in the Western Hemisphere.

Venezuela-China Relations

Over the past two decades, Beijing has persuaded a steady stream of Latin American countries — including Costa Rica, Panama, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras — to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China, often pairing diplomatic pressure with promises of investment and strategic partnership. Venezuela made that switch much earlier, in 1974. Ties deepened after Hugo Chávez took power in 1998, and when Maduro took power in 2013. Maduro even enrolled his son at Peking University in 2016.

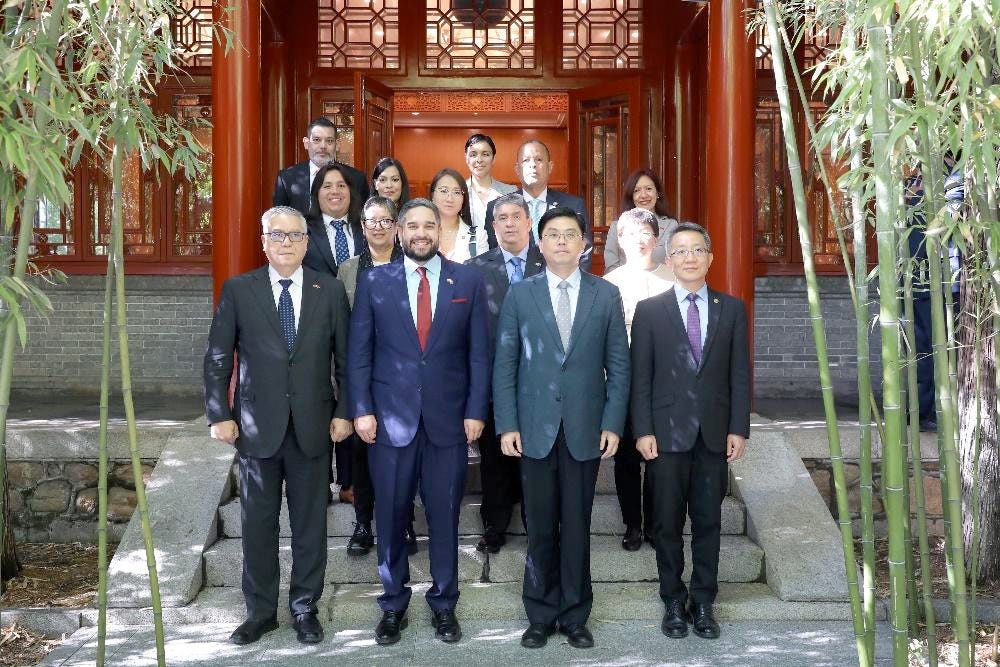

In 2023, China and Venezuela elevated ties to an “all-weather strategic partnership” during a meeting between Maduro and Xi in Beijing, a designation Venezuela shares with only a few other countries like Pakistan and Belarus. But that distinction apparently excluded taking action to defend Venezuela from the US.

The asymmetry in the relationship was visible even at the end. Maduro’s last publicly reported meeting — just hours before his capture — was with a Chinese special envoy sent to reaffirm Beijing’s support. But the meeting was with a relatively low-level Chinese delegation at a moment of acute crisis for Caracas.

The outcome may not be wholly negative for Beijing’s broader regional position. While China stands to lose a sympathetic government in Venezuela, the US move reinforces perceptions of American hegemony and unpredictability, potentially encouraging other Latin American governments to hedge by deepening ties with China.

Oil

Lots of the China-Venezuela coverage so far has focused on oil. Venezuela’s largest crude export destination has been China, and Chinese firms such as China National Petroleum Corp (中国石油天然气集团有限公司) have long been involved in Venezuelan extraction. After Washington tightened oil sanctions in 2019, China halted direct purchases of Venezuelan crude. The oil did not stop flowing to China altogether; instead, it was rerouted through independent traders via ship-to-ship transfers and often relabeled as Malaysian crude, allowing Chinese refiners to keep importing while giving Beijing plausible deniability.

But Venezuela’s oil importance to China should not be overstated. Venezuela accounts for roughly 4% of China’s crude imports, and the country’s overall economic weight is small relative to Beijing’s core energy interests in the Middle East and elsewhere. A US-approved government in Caracas could also plausibly make Venezuelan oil easier for China to access directly by removing the need for sanctions evasion altogether.

Debt

The more consequential material concern for Beijing is probably debt. Venezuela is estimated to owe China roughly $13-15 billion. That exposure helps explain why, following the US capture of Venezuela’s president, China’s top financial regulator reportedly asked policy banks and major lenders to review and report their Venezuela-related risks.

The risk is not simply default, but reprioritization. As The Guardian noted, a government under heavy US pressure could choose to place American creditors and claimants ahead of Chinese ones, leaving Chinese banks to absorb losses. The situation is further complicated by opaque loan terms, oil-backed repayment structures, and the political leverage that often accompanies debt restructuring.

This is where a US-engineered political transition could become thorny for Beijing. Would a new, US-aligned government honor existing Chinese loans and contracts? Would Chinese firms retain access to assets and projects they financed? Or would they be squeezed out under the banner of political realignment? How these questions are resolved could directly affect the US-China relationship amidst its ongoing trade war.

Nick, the "Pinduoduo Radar" line is great clickbait, but it reveals a dangerous complacency in Western analysis.

You are judging the PLA's domestic capabilities based on their "Monkey Export Models." In the arms trade, no Great Power sells its top-tier kit to a client with zero discipline. The radar in Caracas is to the PLA's integrated coastal defense what a 1990s Honda Civic is to a Formula 1 car. Furthermore, Hardware is useless without Software (Discipline). Maduro’s army had high entropy; the PLA has high order. Confusing the two is a fatal intel error.

On the "Failure of the China Model": You imply China failed because it didn't save Maduro. But System B isn't NATO. It doesn't sell "Security Guarantees" (Article 5); it sells "Mercantile Solvency." Maduro was operationally insolvent. He couldn't pump the oil to pay the interest. If the US wants to step in as the new Property Manager and spend billions in CapEx to fix the pumps? Great. The Senior Creditor (China) welcomes the liquidity. China doesn't need a friend in Miraflores; it needs a payer.

On the Taiwan Analogy: This is the most critical distinction. Venezuela was a Raid (Fast, Kinetic, Destructive) on a Commodity Asset (Oil). Taiwan would be a Siege (Slow, Strangulating, Preservative) on a Computational Asset (Chips).

You can snatch a dictator in a morning. But you cannot snatch a 3nm Fab without shattering the wafers inside. One is a police action; the other is a metabolic strangulation. The physics dictate the tactics.

"On Weibo (Chinese Twitter)" - this is a very silly and unserious critique but... 1. You don't have to call it "Chinese Twitter" - we know what it is, or can go find out on our own. 2. If you insist on providing a marker, "Chinese Twitter" is an actively silly way to do it. Twitter matured as a product (saturated market, flat growth, end of the S curve) in early 2016. It changed name to X in 2022.

It hasn't even *been* Twitter for 30% of its mature product life. If you're gonna insist..."Chinese X" would be miles more accurate, even if it punches older internet users in the feels and makes them momentarily sad for The Platform That Used To Be.