Biotech

A Feature: China's Coming of Age

In 2011, China’s drug regulator cleared the nation’s first home-grown targeted cancer pill. Fourteen years later, a Chinese bispecific antibody is aiming to knock the world’s top-selling oncology drug off its perch.

Those two bookends frame twin contests now running in parallel. One is humanity’s decades-long fight against cancer, a disease that still claims one in six lives worldwide. The other is China’s effort to move from importing medicines to inventing them. This article seeks to follow these battles in real time by tracing the stories of four milestone therapies and their makers.

Founded in 2003 in Hangzhou by a team of returnee talent, Betta Pharmaceuticals launched the first targeted anticancer drug developed in China to reach the market. The success of its drug Conmana1 in China dovetailed with sweeping policy reforms aimed at making home-grown medicines more trusted, innovative, and affordable. The drug did not, however, make it outside China, despite Betta Pharma’s best efforts. Conmana is an example of “me too” innovation: a variation on an existing drug that performs just as well but not quite better enough to make it globally competitive.

Created through a rigorous internal drug development program in 2012, BeiGene’s Brukinsa did what Betta’s Conmana could not – it went global, becoming the first Chinese cancer therapy approved by the US FDA. A “me better” innovation targeting blood cancer, Brukinsa now reaches people in over 65 countries, bringing in over US$2 billion in sales annually.

Betta’s Conmana and BeiGene’s Brukinsa are both small-molecule drugs, meaning they are created through chemical synthesis. The real frontier of innovation that excites biotechnologists is biologic drugs, biomolecules such as engineered proteins or RNAs that act with greater power and precision inside the body.

Carvykti is one of the first innovative biologic drugs created in China. Initially discovered and tested in Xi’an Jiaotong Hospital by Nanjing Legend Biotech, the drug reached global markets with the help of Johnson & Johnson. First gaining US FDA approval in 2022, Carvykti now has regulatory approval across over 36 countries and has treated over 5,000 patients, with more to come.

The last story is unfinished. It’s about Akeso’s ivonescimab, an icon of Chinese biotech innovation in mainstream media. A biologic drug with a novel method of targeting cancer, ivonescimab received approval by the Chinese NMPA in April 2025. In countries like the US, where Akeso has passed the baton to US-based Summit Therapeutics to develop the drug, ivonescimab is still in the clinical trial phase, meaning it has yet to pass through the regulatory gauntlet. What’s exciting and undecided about ivonescimab is its potential to go head-to-head with the world’s best-selling drug, Keytruda. Whatever happens to ivonescimab over the next few months in trials outside of China will send a signal of exactly how successful Chinese biotech innovation has become. The world of biotech will be watching closely.

But let’s start from the beginning. Betta Pharma’s milestone achievement of Chinese regulatory approval for a new innovative drug (2011) happened only 11 years before Akeso’s ivonescimab earned a US$5 billion deal with Summit Therapeutics (2022). How did we get here?

Betta Pharma: The “Me-too” Era

In the 1990s, biopharmaceuticals — specifically oncology, the study and treatment of cancer — entered a new era of innovation. Up until the early 2000s, doctors primarily combated cancer with broad-stroke methods like surgery and chemotherapy. Now, new and improved methods were emerging: targeted therapies that zeroed in on cancer cells while minimizing damage to healthy cells and immunotherapies that helped the body’s immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.2

This revolutionary effect of molecular biology captured the attention of many bright scientists and doctors in China, including Dr. Wang Yinxiang 王印祥. Born in rural Hubei, he spent three years working in public health and three years completing a Master’s degree at the Chinese Academy of Medicine before he could truly follow his passion for oncology to the United States, where he earned a doctorate from the University of Arkansas.

Dr. Wang got his wish to do cutting-edge research as a postdoc at Yale, where he dove into one of the first targeted cancer therapies, Novartis’ Gleevec. Sharing his apartment was Ding Lieming 丁列明 – another Chinese transplant with a University of Arkansas MD. On strolls through New Haven’s Science Park, the two friends along with medical chemist and entrepreneur Zhang Xiaodong 张晓东 bonded over more than just science. They shared a bigger dream: to bring the newest in biotech to China.

Dr. Wang and Dr. Ding would ultimately join forces in 2003, when they founded Betta Pharmaceuticals to develop targeted cancer therapies in China. Betta opened its doors with a shoestring team – just 13 people, many of them what Dr. Wang affectionately called “kids,” fresh from bachelor’s or master’s program and learning on the fly. Nevertheless, they managed to develop icotinib (later sold as Conmana), a drug engineered to target EGFR proteins as a way to inhibit cancer cell growth.

In those years, China’s pharmaceutical industry hadn’t left the nest. Manufacturing of cheap, generic drugs dominated. To domestic investors, companies, and physicians, a business model built on new drug development was unthinkable: the costs and risks were too high, the regulatory process was a mess, quality and safety were still iffy, and previous such attempts had failed. Winning a clinical-trial slot for Conmana (a prerequisite for proving the drug could outshine current care) was nothing short of herculean. When the Peking Union Hospital director declared the study too risky and tried to dismiss him, Dr. Wang stood firm for ninety minutes, knocking down every objection until the approval stamp finally came down in his favor.

In 2009, Conmana made it to Phase III clinical trials, the make-or-break test of wide-scale efficacy. In Phase III, the team pushed the envelope again: rather than testing against a placebo, they pitted their molecule against AstraZeneca’s gefitinib (the world’s first targeted anti-cancer therapy) in the first Chinese study to challenge an imported standard head-to-head.

The study’s results, announced by leading academic Sun Yan at the 2011 World Lung Cancer Conference – also the first time a China-developed drug headlined an international academic forum – showed that icotinib could match the cancer-fighting power of the imported benchmark while causing fewer side -effects. Conmana, in other words, was a successful “me-too” drug, an incremental improvement on an existing pharmaceutical innovation.

After six grueling years, Conmana earned its first regulatory approval from China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA; although at that time it was still the CFDA).

Betta’s success as a fast follower of a next-generation cancer therapy was a triumph for Beijing’s returnee talent and national innovation programs. Conmana’s success had been fueled by funds from the Yuhang District Government of Hangzhou, the “863” Program, and the “11th Five-Year Plan” National Science and Technology Major New Drug Special Project.

The government showered Betta with accolades: the China Overseas Chinese Contribution Award, the gold prize for patents, first prize for the National Science and Technology Progress Award, and more. Chen Zhu, then Minister of Health, praised their achievement as “an emblem of ‘Two Bombs and One Satellite 两弹一星’ in the field of public health,” referencing a techno-nationalist ideal of a whole-nation project for science and technology development.3

However, for all its homegrown glory, Betta’s blockbuster never crossed the border.

In 2014, with the help of Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Betta filed to run a clinical trial for Conmana in the US, the first step towards seeking US FDA approval. However, the trial was shortly withdrawn. Newer, later-generation EGFR inhibitors were eclipsing Conmana’s performance, and there was no sense investing in trials when the product was unlikely to sell.

Though just a “me-too” innovation, Conmana was a landmark accomplishment for China. On the domestic market, the drug was meaningfully cheaper than its imported alternatives. Given the rapidly growing incidence of lung cancer in China, Conmana’s improved affordability made a real difference in patients’ lives. Still, it would take almost another decade before a China-developed cancer drug would make a global impact.

BeiGene: A “Me-Better” Drug Goes Global

China’s mix of capital, talent, and policy reforms was turning its budding biopharma sector into a global magnet.

Among the first drawn in was Pittsburgh native John Oyler. Familiar with China through his work at McKinsey in the 1990s, Oyler was stunned by the country’s science and technology progress when he returned the next decade. By the mid-2000s, regulatory harmonization, returning talent, and improved manufacturing infrastructure enabled China to meet the needs of global pharmaceutical companies, leading to the growth of contract research organizations (CROs), which provide outsourced medicinal science services. Oyler co-founded one such Chinese CRO, BioDuro, in 2005.

But serving foreign pharma clients wasn’t enough. As China moved toward deeper healthcare reform, Oyler saw an opening for homegrown innovation: “[China] had the capability to pour tens of billions of dollars back into the global industry to help pay for more research, which would not only make drugs more affordable in China, but across the globe.” Rather than repeat the trajectory of BioDuro, which was eventually sold, he wanted to create something enduring. “I wanted to build something here — in China — that is lasting, impactful, involved in great science, and can really help people,” he said. He aspired to create a company capable of developing world-class cancer therapies from a country many still underestimated.

To bring his vision to reality, Oyler needed scientists. He connected with Dr. Xiaodong Wang 王晓东, a top Chinese American academic biologist who recently returned to China to lead the new Beijing Institute of Life Sciences. The chance to work with Dr. Wang — a superstar scientist admired widely enough to impress parents at Chinese New Year — proved an effective tool for attracting talent. Together, they founded BeiGene in Beijing in 2010 to become the “Genentech of China.”

Early on, BeiGene focused on BTK inhibitors, a targeted cancer therapy that works by blocking cancerous B-cells’ ability to grow. The first BTK inhibitor, synthesized in 2007, showed promise but caused significant side effects. In 2012, BeiGene initiated a discovery program in San Mateo and Shanghai to develop a better BTK inhibitor. After screening over 3,000 compounds, the team identified the highest-potential molecule that would eventually become Brukinsa (zanubrutinib).

BeiGene aimed to take Brukinsa global from day one. To support worldwide approvals, the company built a 25-country trial program in which approximately 90% of patients were enrolled outside of China. The numbers delivered: Brukinsa consistently beat first-generation BTK inhibitors on safety and efficacy, turning a presumed “me-too” into a clear “me-better” that is now the standard of care for B-cell cancers.

Momentum snowballed. In 2019, Brukinsa set a precedent as the first Chinese-developed cancer therapy to win FDA approval, months before China’s own NMPA signed off. It has since secured clearances in 65-plus markets spanning the US, EU, Canada, Australia, Japan, and China, and now supplies more than half of BeiGene’s revenue with US$2.6 billion in 2024 sales. The company (rebranding as BeOne) has likewise gone global, conducting trials in over 45 countries.

Legend: A True Chinese Biologic

Witnessing the breakthrough of firms like BeiGene, Beijing set its sights on higher-value innovation. The State Council’s 2016 13th Five-Year Plan therefore called for “leapfrog development in the biopharmaceutical industry,” spotlighting cell and gene therapies, antibodies, and vaccines.

These platforms fall under biologics — large molecules derived from biological processes such as insulin and hormones — rather than small-molecule drugs such as Betta’s Conmana and BeiGene’s Brukinsa. Because biologics are bigger and more structurally complex, their effects are harder to predict and their manufacture far costlier, but they open therapeutic doors that chemistry alone cannot.

Founded in 2014 as a subsidiary of GenScript, Legend Biotech embodied the kind of biologics leadership the state now prioritized.4 After losing his father to cancer, co-founder Frank Zhang 章方良 united with Chief Scientific Officer Dr. Frank Fan to create the firm with the goal of advancing oncology.5

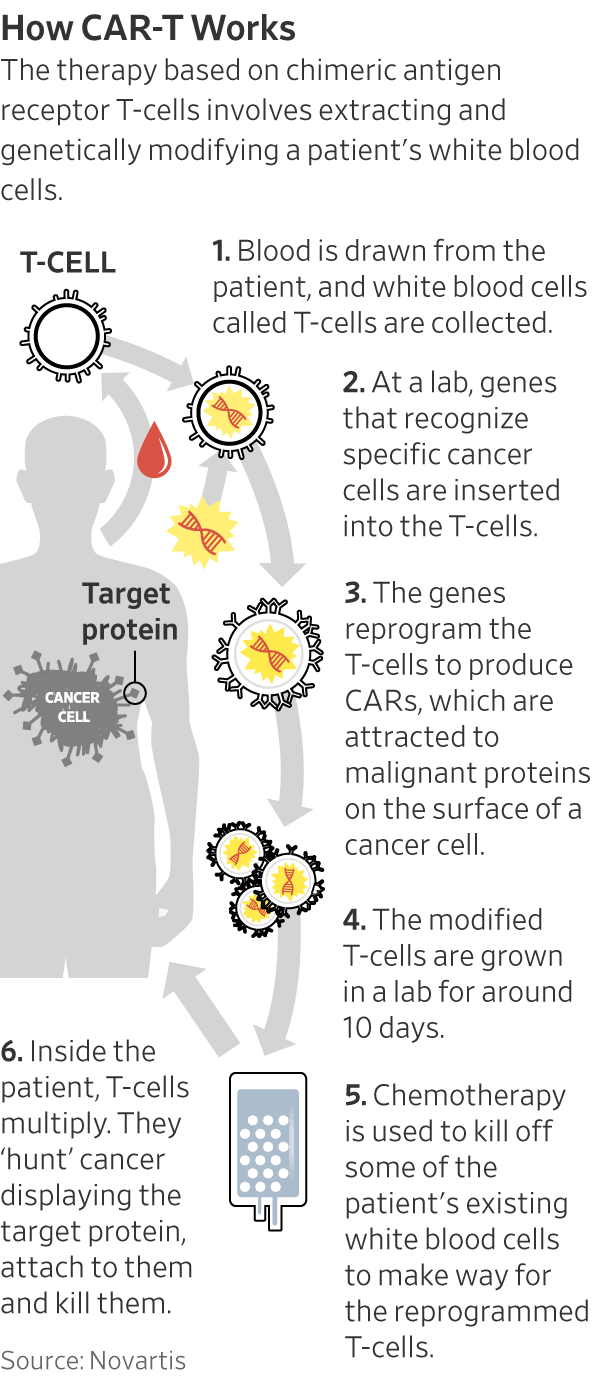

At that time, influential scientific journals, Big Pharma deals, and first-in-human successes had converged to position cell and gene therapies as the vanguard of biopharmaceutical innovation. Early successes led by the University of Pennsylvania highlighted the potential of CAR-T therapy,6 a type of treatment in which a patient’s disease-fighting T-cells are genetically engineered to seek and destroy cancerous cells.

Driven by the promise of next-gen cancer therapy, Legend’s 19-person team, working in “a room the size of a freight elevator,” crafted a second-generation CAR-T treatment targeting multiple-myeloma tumor cells (later sold as Carvykti). Leading the research was Dr. Frank Fan, who had studied at Xi’an Jiaotong University and worked at the Xi’an Jiaotong Hospital. Leveraging those ties, Dr. Fan was quickly able to initiate Legend’s first CAR-T clinical trial at Xi’an Jiaotong Hospital, turning the startup into a “dark horse” contender in the CAR-T space.

At the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Legend presented early-phase data from its trials in China: durable remissions in multiple-myeloma patients with only mild side effects. The first of its kind accepted for review by China’s NMPA, this CAR-T candidate signaled that the country could innovate well beyond small-molecule chemistry.

Such promising results drew members of the global life sciences community. J&J’s Janssen signed a partnership with Legend Biotech in 2017. This was a case of an outlicensing deal: when a company (such as Legend) sells or grants rights to a drug candidate, passing the baton to a different company (such as Janssen), which who takes on the responsibility to bring the drug through testing, approval, manufacturing, and commercialization. Such transactions are the lifeblood of the industry. However, the high-potential molecules worth such high-profile deals didn’t historically come from China.

With the combined efforts of Legend and Janssen, Carvykti won FDA approval in 2022, soon followed by clearances in the EU, UK, Japan, and Canada. Though not first-to-market, Carvykti’s superior clinical value crowned it best-in-class. This then completed China’s rapid climb from “me-too” copies, through Brukinsa’s “me-better” gains, to a world-leading biologic breakthrough.

Akeso: a top challenger emerges

Now, Akeso Biopharma’s new molecule is drawing notice as a likely first- and best-in-class therapy from China.

Akeso started as the dream of Dr. Michelle Xia, a Gansu native. While working for California-based Crown Bioscience and in other roles in the US and UK, Dr. Xia grew frustrated with the eight-to-ten-year delay it took for innovative overseas therapies to reach Chinese patients. So she and three partners founded Akeso in 2012, naming it after the Greek goddess of healing, with a mission to develop home-grown therapies for cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Akeso’s edge is bispecific antibodies (BsAb), a type of next-generation cancer treatment involving engineered proteins that strike two targets at once, such as igniting immune cells while starving tumors. The first proof arrived in 2022 when China’s NMPA cleared Akeso’s Kaitani (PD-1/CTLA-4), the world’s first commercialized BsAb.

Next came ivonescimab, a PD-1/VEGF bispecific now pushing Akeso onto the global stage. By jointly blocking an immune checkpoint and tumor blood-vessel growth, it qualifies as first-in-class – an industry term for a drug that introduces a truly novel therapeutic approach.

In June 2022, Akeso unveiled the Phase II results of ivonescimab at the annual ASCO conference, showing strong responses in non-small cell lung cancer. Just months later China’s NMPA granted the drug Breakthrough Therapy status for three medical use cases, enabling closer guidance and fast-tracking its review.

Sensing ivonescimab’s scientific and commercial potential, US-based Summit Therapeutics inked a massive deal in December, licensing Akeso’s innovation for up to US$5 billion.7 The corresponding press release hailed Akeso’s innovation as “the PD-1 / VEGF bispecific antibody that is most advanced in the clinic,” noting that neither the FDA nor EMA had yet approved any PD-1-based bispecific therapy.

The size and significance of this agreement marked a bellwether moment in Chinese biotech innovation. Blue-chip investors and multinationals began scouting the country for genuinely novel assets rather than low-cost manufacturing plays.

China’s slice of global out-licensing has since tripled to 12%, with deal value leaping from US$35 billion in 2023 to more than US$46 billion in 2024. This trend seems set to continue through 2025 and beyond.

The fate of ivonescimab and most other compounds covered by these recent deals is uncertain. Many drug candidates are purchased in the preclinical or Phase I stage of development, requiring another 5+ years and US$300+ million dollars before they pass the clinical and regulatory hurdles necessary to make it to market – or, they will fail, like roughly 90% of compounds that enter human trials. Only five China-originated drugs have ever cleared the US FDA (BeiGene’s Brukinsa and Legend’s Carvykti are two of them).

Ivonescimab could be next. Akeso’s molecule has already completed Phase I and Phase II, and is in the midst of several high-stakes Phase III trials. Its Phase III trials with Chinese patients have already demonstrated success, leading to two recent NMPA approvals in the spring of 2025. The defining test comes next: a Summit Therapeutics-run Phase III study spanning 108 locations in 12 nations, where the drug candidate must outshine oncology’s gold standard, Keytruda.

Keytruda (drug name pembrolizumab) has been described as “era-defining,” the “800-pound gorilla” of the class of drugs to which ivonescimab also belongs. Developed and commercialized by American multinational Merck, the drug has been approved for 41 indications8 across 18 types of cancer. It’s the world’s best-selling drug, raking in about $29.5B in 2024 – nearly half of Merck’s total revenue. Its upcoming 2028 patent expiry opens the field for new challengers.

Akeso’s ivonescimab could be one such challenger. If its global Phase III trial confirms that the drug’s positive risk-reward results can extend beyond China’s borders, Akeso’s first-in-class molecule may eventually also prove to be best-in-class, making it one of the biggest biotech stories of the decade.

On the horizon

Together, Conmana, Brukinsa, Carvykti, and ivonescimab trace a clear, but incomplete, arc: China’s pharma sector has evolved from reverse-engineering proven ideas to originating drugs that can contend for global standards. Each milestone marks a step from “good enough at home” to “competitive abroad,” showing how policy shifts, capital inflows, and returning talent have reshaped the industry’s ambitions and capabilities.

Those four successes are only a sliver of the story. Dozens of other firms have logged incremental wins, and many more have stumbled in clinical trials or overseas filings. With financing tightening, patent cliffs approaching, and regulatory expectations rising, the next crop of candidates will test whether China’s momentum is structural or situational. The outlook could range from steady gains in select niches to a broader slowdown if capital or policy tailwinds fade.

Whatever the trajectory, one fact persists: cancer is indifferent to where a molecule is conceived. Progress depends on tapping every credible lab and idea, whether in Boston, Basel, or Beijing. If Chinese innovators add new options to the world’s oncology toolkit, patients everywhere stand to benefit — and that, ultimately, is the benchmark that matters.

Author’s note: drugs that have already received market approval will primarily be referred by their trade name, i.e. under what name they are distributed to patients. When discussing the molecule itself, especially during its history and phases of development prior to commercialization, the drug name may also be used. Since they are chosen for intellectual property and marketing purposes, brand names tend to be shorter, more memorable, and more easy to distinguish than the drug name. Akeso’s ivonescimab, because it is still in earlier stages of trial, will only be referred to by its drug name.

See this chart:

The slogan “Two Bombs, One Satellite” points to three milestones: China’s first atomic bomb (and later hydrogen) bomb tests, its intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), and its inaugural artificial satellite.

Legend Biotech has since removed its subsidiary relationship with GenScript in the face of geopolitical scrutiny in 2024.

Not all parts of this are a success story. In 2020, Zhang resigned after being investigated and arrested for breaking import and export regulations by smuggling human genetic resources. In 2022, mere months after Carvykti’s first approval, CSO Dr. Fan suddenly left, sparking speculation around internal power struggles.

Akeso received an upfront payment of US$500 million and eligibility for milestone payments (based on specific goals like successful clinical trial results, regulatory approvals, and sales targets) worth up to US$4.5 billion. Summit received the rights to develop and commercialize ivonescimab in the US, Canada, Europe, and Japan.

An indication refers to the specific medical condition or disease for which a drug is approved to treat, prevent, or diagnose. To secure FDA approval for a particular indication, a pharmaceutical company must demonstrate that the drug is both safe and effective for the intended use. Importantly, each new indication requires a separate approval process, even for already approved drugs. This ensures that the drug's use is supported by robust evidence for each specific condition.

Nice piece. The summit results at ASCO looked slightly worrying so we will have to see