Hovercraft Invasion, Labubu, Tea

Friday Bites!

RAND’s Compute Cluster is Hiring

We’re particularly excited about applications from ML engineers and semiconductor experts eager to shape AI policy as well as seeking excellent generalists excited to join our fast-paced, impact-oriented team. Find an overview here. More details below.

The team's work focuses on using compute as a governance tool, but extends to technical AI governance more broadly, including: technical mechanisms for AI governance (e.g., verifying AI agreements, hardware-enabled mechanisms), AI infrastructure (policies, trends, and forecasts), and export controls (designing effective restrictions, assessing their impact, and fixing them). We've achieved strong "product-market fit" for our work—our technical analyses inform major policy decisions and leading AI companies and governments regularly seek our input.

The roles are: Technical AI Policy Associate & Technical AI Policy Research Scientist (senior). Applications are accepted on a rolling basis.

Why China Wants to Steal the Secrets to a Chunky Soviet Hovercraft

Lily Ottinger reports:

Earlier this month, the New York Times obtained an internal document from the Russian Federal Security Service detailing the threat of Chinese espionage. The report specifically outlines a Chinese campaign to snag Soviet aerospace engineers:

China has long lagged behind Russia in its aviation expertise, and the document says that Beijing has made that a priority target. China is targeting military pilots and researchers in aerohydrodynamics, control systems and aeroelasticity. Also being sought out, according to the document, are Russian specialists who worked on the discontinued ekranoplan, a hovercraft-type warship first deployed by the Soviet Union.

“Priority recruitment is given to former employees of aircraft factories and research institutes, as well as current employees who are dissatisfied with the closure of the ekranoplan development program by the Russian Ministry of Defense or who are experiencing financial difficulties,” the report says.

An ekranoplan (literally “screenglider”) is an airplane-esque vehicle designed to fly closely above a body of water, utilizing the ground effect to reduce drag and achieve greater fuel efficiency. From 1966 to 1988, the world’s largest and heaviest aircraft was a classified Soviet ekranoplan dubbed “The Caspian Sea Monster,” which had a maximum takeoff weight of 544,000 kg and a wingspan of 37.6 meters. Since they fly just a few meters above the water, Ekranoplans operate outside the range of detection for many radar systems.

But why is China so interested in acquiring this technology?

Ekranoplans could possibly be used to ferry troops across the Taiwan Strait (the US Navy estimated that some Soviet ekranoplans could carry up to 850 troops or two tanks), although flying over the open ocean can be challenging for ground effect vehicles. The water below the craft must be calm, with waves below 1.25 meters in height; otherwise, the air cushion becomes unstable.1

Regardless, it would technically be possible for Ekranoplan-style warships to fly over the Taiwan Strait on calmer days, and the PLA isn’t considering launching an invasion in the middle of typhoon season anyway.2

With influence from Soviet designs, China has built smaller Ekranoplans like the DXF-100, the Albatross-5 (信天翁5), and the Neptune-1 (海王一号), which can hold 15 to 20 passengers. But it seems that China is more inclined to apply techniques of Ekranoplan design to other technologies. Ekranoplan engineers are intimately familiar with both hydrodynamics and aerodynamics, so perhaps China’s simply believes that these are the most cost-effective engineers to target. But apart from generic overlap with shipbuilding and aircraft design, there is a direct technological crossover between ekranoplans and wing in ground effect drones (WIG UAVs), which are basically like tiny unmanned ekranoplans. The first reports of Chinese military WIG drones surfaced in 2017, and were quickly recirculated by state media rather than being censored. WIG drones are also being developed by Gdańsk University of Technology in Poland and a Danish startup. These drones could be used for naval reconnaissance, transporting goods, or delivering payloads, all while flying outside the range of aircraft detection radar.

While the extent of China’s espionage activities in Russia doesn’t bode well for their partnership (I highly recommend you read the whole NYT article), China appears to have extracted plenty of value from Russian scientists already. Hopefully, Taiwan has a plan to deal with low-altitude amphibious drone swarms. Who knows? Maybe Taiwan has its own team of disillusioned Soviet scientists waiting in the wings.

How China’s Gen Z Is Exporting Chinese Soft Power to the World

Selina Xu is a writer and researcher on technology. She was a former China reporter at Bloomberg News.

Helen Zhang is the co-founder of Intrigue Media and a non-resident fellow in the United States Studies Centre's Emerging Technology Program. She was previously an Australian diplomat.

Since America’s “Liberation Day” tariff blitz, a lot has been said about China’s economic and technological self-reliance, which has given it more leverage in this trade standoff. Under Xi Jinping, China has steadily focused on reducing dependence on Western supply chains and the U.S. dollar, while swamping the world with goods.

Much less has been said about China’s growing cultural self-sufficiency and ability to export soft power. Just a decade ago, Marvel movies topped the Chinese box office while Japanese video games and Taiwanese soap operas occupied the pastimes of youths. In 2025, the highest-grossing movie in China (and in the world) is Ne Zha 2, an animated retelling of a traditional Chinese myth. On Youtube and other streaming platforms, historical costume dramas — often featuring palace intrigue or celestial romance — have gained traction with overseas audiences, especially in Southeast Asia. On phones and PCs, Chinese games like “Genshin Impact” are winning hundreds of millions of players at home and abroad.

The ascendance of domestic content is in part a result of the Chinese government’s push for national rejuvenation through restriction of foreign content—for example, a nearly decade-long unofficial ban on Korean entertainment, including K-pop, when South Korea angered China by agreeing to allow a U.S. missile-defense system on its soil. On April 10, China said it would cut back Hollywood films in retaliation for U.S. tariffs.

But part of this phenomenon is driven by China’s Generation Z, a 270-million-strong cohort born since the mid-1990s, who are more culturally confident and cosmopolitan in their tastes — and willing to pay for good content. Already, Gen Z accounts for 40% of consumption in China, and their influence will only grow, with spending set to surge fourfold to 16 trillion yuan ($2.2 trillion) by 2035.

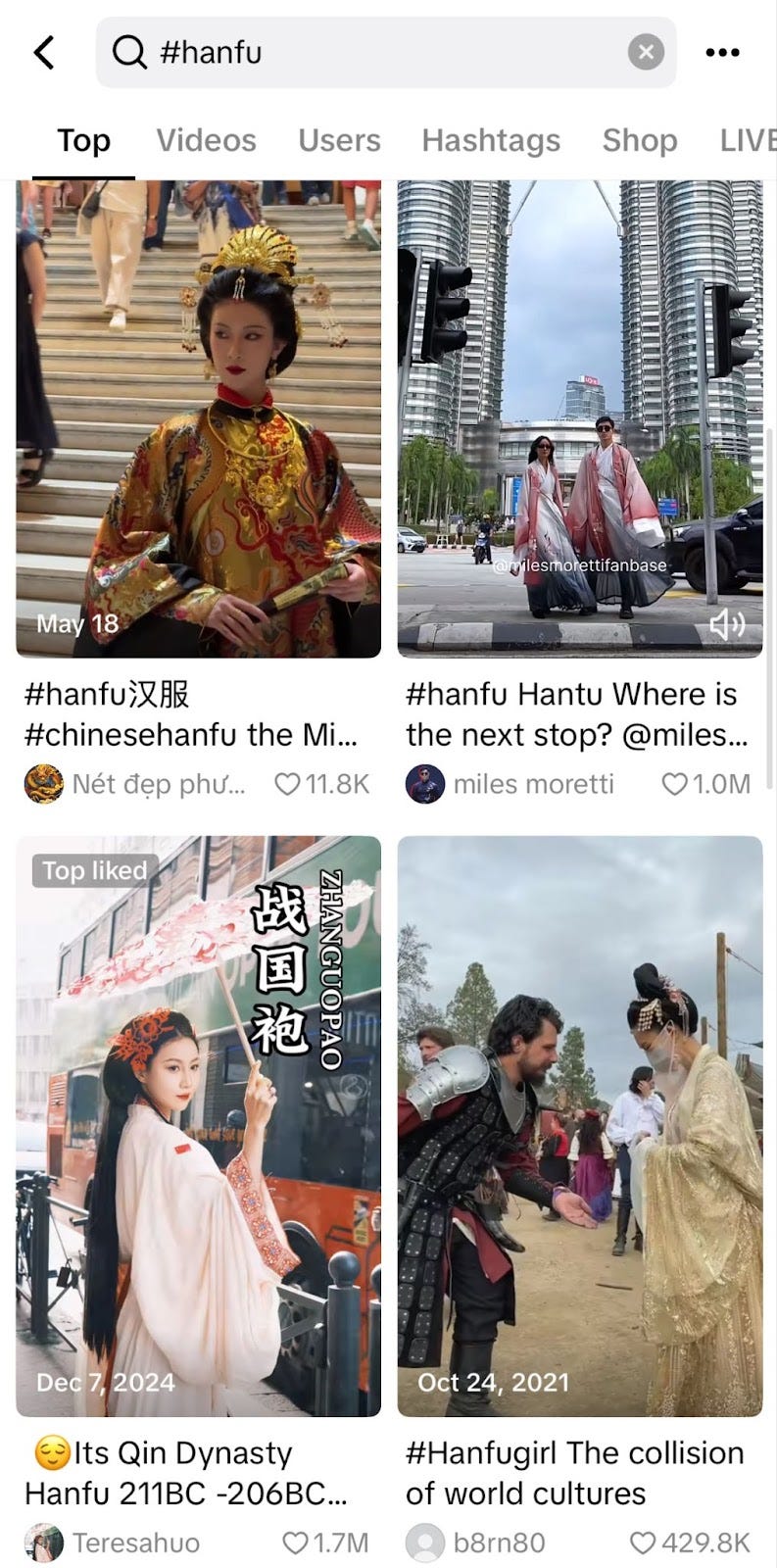

In recent years, blockbusters like Chang An and Jiang Ziya and popular TV series like Empresses in the Palace and Nirvana in Fire underscore how the youth are gravitating towards traditional Chinese heritage. Some of these draw from epics like Journey to the West, which is one of China’s most-read literary masterpieces, and The Investiture of the Gods, a 16th-century fantasy novel about gods and demons. Others are set in various historical dynasties, but one that comes to the fore is the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-907) — dubbed China’s golden age — when its empire was at its most powerful, and when the ancient Silk Road was at its peak. Some have attributed this solely to nationalism, but Gen Z’s love of history is authentic, imbued partly by an education system emphasizing “five thousand years of Chinese civilization.” In 2024, over 62 percent of visitors to China’s national museum were under the age of 35. Wearing hanfu — a style of clothing with flowing robes that dates back more than two millennia — has also ballooned from a niche hobby to a billion-dollar market in China and a global movement on TikTok. When one of us visited Xi’an last year, the ancient capital’s city walls were overflowing with young people dressed in hanfu.

China isn’t alone in indulging in nostalgic, domestic revival — in some ways, this isn’t too different from Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again,” Britain’s Brexit reminiscence of its pastoral and colonial past, or Putin’s harking back to imperial glory. But Xi Jinping’s ambitions go beyond a mere exercise in nationalism, and should not be construed as isolationism. In his April 16 essay in Qiushi Journal, the flagship magazine of the CCP, Xi wrote, “To build a culturally strong nation, we must more proactively present China’s perspectives, spread Chinese culture, and showcase China’s image — ensuring our soft power matches our hard power, converting our developmental advantages into discourse power.” Beijing is keen on deepening ties with regional neighbors, especially Southeast Asia, which has also been hard-hit by American tariffs but already has a glut of Chinese goods. To bind South-East Asia’s economy more tightly to China’s, soft power can grease the wheels.

One area where Chinese soft power is growing is the gaming industry. By some counts, over 500 million people in China are consumers of anime, comics, and gaming, most of whom grew up watching Japanese anime but are increasingly embracing local content. The rise of the genre can be seen in the trajectory of Bilibili Inc, a Chinese streaming platform that started off as a niche site for anime and gaming fans but has now become a $9 billion public company that dictates mainstream trends — the platform has about 30 million paid subscribers (that’s more than ESPN), who are mostly Gen Z. Young Chinese men are playing “Genshin Impact” and “Honor of Kings” — two of the world’s most lucrative mobile titles and both Chinese-made — while women are playing Chinese otome games that have interactive romance storylines. As local game studios beef up to cater to increasing interest at home, many of these games are also making waves abroad. For instance, the wildly popular “Love and Deepspace” became the most-downloaded and top-grossing interactive story mobile game in Japan last year. Four of the ten top-grossing game publishers in the world last year were from China, according to analytics company AppMagic.

After decades of importing content from abroad, China is now exporting culture to the rest of the world.

China Gen Z’s tastes in apps and brands are also making inroads overseas. Rednote, which has billed itself as a “lifestyle bible” and is especially popular among young women, is China’s fastest-growing social media platform. The company, a surprise winner of America’s early-2025 TikTok ban, has seen global daily active users up 28% in March from last December. On the app, users share lifestyle content featuring a dizzying array of Chinese brands — many of which are now coming to the West. One example is Pop Mart. The maker of Labubu dolls saw its non-mainland revenue grow by 375% in 2024, accounting for about 40% of its total revenue. Another example is Chinese bubble tea — including brands like Molly Tea and HEYTEA — which have popped up on the streets of New York and California, with distinctive aesthetics, lounge-like ambience, and some selling branded tote bags and cups à la Starbucks. In a sign of their growth, at least four Chinese bubble tea brands are preparing to go public in Hong Kong.

To be sure, the government has been a visible hand guiding tastes, though not often successfully. In recent years, alongside a tech clampdown, the Chinese government has tightened its grip on cultural industries, banning “effeminate” men and hip-hop culture on TV, cracking down on idol fangroups, and championing programs that “vigorously promote excellent Chinese traditional culture, revolutionary culture and advanced socialist culture.” More nationalist epics featuring Chinese resistance efforts during the Sino-Japanese War have dominated the silver screens, alongside anti-corruption TV series like In the Name of the People and The Knockout.

As the U.S. turns more isolationist, slashing foreign aid and imposing tariffs on developing countries that depend on export-driven growth, China now has an unprecedented soft-power opportunity to fill the void. While China’s ability to step in could be constrained by the economic challenges it faces at home (the country has scaled back on big infrastructural loans), cultural and technological exports — from games and movies to TikTok and RedNote — will be one way for China to draw closer to the Global South. As Beijing looks to find other outlets for trade, we expect it to wield more soft power, turbocharged by Gen Z consumption, especially in fast-growing markets like Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa. After decades of Hollywood and Silicon Valley’s dominance, the world is now standing on the cusp of China Inc.

Dissecting Taiwan’s Chip Industry

Aqib is a graduate of Harvard University from the Regional Studies—East Asia program. Today, he presents his research on Taiwan’s semiconductor industry.

With waves of export controls from the United States and economic pressure from China, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry — its crown jewel — has been facing the heat from both sides. But headlines often miss the mark by addressing the industry as a monolith. With lengthy supply chains including electronic design automation (EDA) software, equipment, design, manufacturing, and packing, the different sub-industries all have their own economics, and their experiences all vary.

So let’s look at a few examples from the most-discussed sub-industries: advanced manufacturing, mature manufacturing, advanced design, and mature design. Their realities have all been warped in different ways by the recent geopolitical landscape; some have been cruising while others have been collapsing, yet two factors commonly mark their experiences: the tenacity of Chinese companies to get the chips they want, and the AI boom creating profits for anyone who can latch onto it.

Advanced Manufacturing: TSMC

TSMC, has fared remarkably well since BIS export controls. Recent news of the U.S. banning TSMC from all AI chip exports to China in 2024 and a potential billion-dollar fine may seem frightening, but these incidents are overshadowed by TSMC’s continual growth in the Chinese and global market from AI demand. The reason for TSMC’s staying power in the Chinese market (as shown below) is that there is simply no other alternative. If you want to make an advanced chip for AI or other high-performance computing (HPC) applications, TSMC is the only company that can do so. Despite export controls, TSMC’s revenue from China has only increased, and the share of revenue from China has remained relatively steady.

In the face of export controls, how do Chinese designers place orders with TSMC? The answer lies in downgrading and going for so-called efficiency rather than raw power. Chinese AI companies like MetaX (沐曦) and Enflame (燧原科技) reportedly downgrade their chip designs to be just within performance restrictions enforced by BIS export controls. Besides simple downgrading, Chinese companies have begun to focus more on ASICs and FPGAs, less versatile yet still strong chips that can be programmed for specific applications. BITMAIN (比特大陸), which was the cause of TSMC’s recent explosion of sales to China, has been able to buy up leading-edge 3nm chips from TSMC by designing ASICs for Bitcoin mining and AI applications.

How effective these downgraded chips and ASICs are is still an open question. Of course, Chinese companies will say their chips are comparable to GPUs from NVIDIA, and, in theory, Chinese firms can go far with such chips. Basically, instead of asking for a juiced-up GPU that can do everything, they are designing an ASIC that can do a limited set of tasks just as well but flounder at everything else. This strategy could allow China’s AI push to persist despite export controls, especially if they can make up for the weaker semiconductors with better code.

But regardless of whether these chips accomplish their goals, Chinese firms continue to buy them, and thus, TSMC continues to prosper.

Mature Manufacturing: Powerchip

However, the same cannot be said for Taiwan’s mature manufacturing foundries. A perfect storm of COVID-19 and increased Chinese competition has plunged companies like Powerchip into darkness, as the graph below shows.

Mature node manufacturers like SMIC and Hua Hong have been running Taiwanese firms out of business. With subsidies enabling Chinese fabs to cut costs and pressure for Mainland companies to “buy Chinese,” Powerchip is losing the battle for the Chinese market, and Taiwan’s mature chip industry needs to find business elsewhere.

Despite the downturn, Powerchip has found a few growth strategies that serve as a model for Taiwan’s other mature foundries, like UMC. One of these ideas is the Fab IP model. As governments increasingly treat semiconductors as a national security product, Powerchip is attempting to monetize their experience in making and running fabs.

In the Fab IP model, Powerchip signs agreements with other countries and assists in fab planning and operations, while ideally avoiding the construction and operating costs. Powerchip signed such an agreement with India’s Tata Group, which agrees to pay Powerchip royalties for technology transfer while raising the funds for the fab itself. The Indian fab won’t be operational until 2026, but the Fab IP model opens doors for Powerchip’s business. They can no longer compete with Chinese firms on price, but maybe they can compete vicariously through Indian or other foreign fabs. Powerchip is reportedly in talks with Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Poland over similar agreements.

Powerchip’s other method for survival is latching onto the AI boom. For TSMC to make AI chips, they require CoWoS packaging technology, which relies on relatively unsophisticated silicon interposers. With CoWoS demand greatly surpassing supply, Powerchip has been able to insert itself into the AI supply chain. In 2024, PSMC opened a new fab in Tongluo, Taiwan, dedicated partially to manufacturing the silicon interposers required for CoWoS for TSMC. Thus, PSMC can still ride the advanced manufacturing AI wave. Advanced packaging demand has shown no signs of slowing down. With TSMC intending to ramp up CoWoS nearly threefold by 2026, Powerchip’s Tongluo fab will certainly be needed.

Advanced Design: Alchip

Taiwan’s advanced design industry has been able to thrive despite export controls. Let’s take Alchip, Taiwan’s #1 AI company, as an example. Their revenue has skyrocketed in recent years, and they have been able to pivot from the Chinese market to the American one as an engine for its growth. (This pivot accelerated when the U.S. placed their biggest customer, Pythium, on the Entity List in 2021.)

Alchip’s success is partially based on its unique position as an ASIC designer during the AI boom. Chinese customers, particularly automakers, still like to use Alchip, since their products are usually not restricted by export controls. However, although the cost of designing a leading-edge chip can run hundreds of millions of dollars, other Mainland designers exist at the leading edge.

Besides its specialty in ASIC design, Alchip has found success through a partnership with TSMC. As a “pure-play design company,” Alchip maintains a close partnership with TSMC, a pure-play foundry, and the design company has a knack for reserving limited fab capacity at TSMC. In particular, Alchip has often been able to gain “capacity support” for the critical CoWoS packaging mentioned earlier.

As American companies are chomping at the bit for AI chips, Taiwanese design benefit from being right next door to TSMC. Alchip has assisted Amazon and Intel in designing their own AI chips to compete with NVIDIA’s GPUs. For the next two years, Alchip orders are skyrocketing with chips for just these two companies, and these orders enable Alchip to keep pushing to the next node.

Taiwan’s advanced design companies have lost out on Chinese business either from customers getting Entity Listed or from Mainland competitors, but these losses have coincided with explosive growth from AI demand. The growth has greatly outweighed the losses, and advanced designers do not seem to be under fire.

Mature Design: Weltrend

The tragic character in Taiwan’s semiconductor soap opera is the island’s mature design sector. This sub-industry has historically been the most reliant on the Chinese market, and these firms are the ones facing the toughest fallout from Chinese competition.

These companies have limited options for survival. Some are attempting to switch to using Mainland fabs to manufacture their chips, risking unintentional technology transfer for only marginal benefits in cost. Mainland competitors can sell chips at a price that would only cover the production costs of Taiwanese mature firms, thanks to subsidies and government help. Taiwan’s mature companies are not as easily able to pivot to the world market either — in the mature chip market, cost is everything. No one wants their TV or microwaves or other analog products to be more expensive.

So how can these companies survive? Taiwan’s Weltrend puts forth one route for relief: taking advantage of the AI boom. Unable to design leading-edge GPUs or ASICs, though, Weltrend is attempting to cement its niche in server cooling fans.

By offering the best chips for server cooling by combining their design skills with developed algorithms, Weltrend hopes it can raise sales for its products as the rest of AI sales go up. These server cooling chips are needed in every data center. This kind of niche in the AI periphery is what some mature firms call the “garnishes for the steak.” They cannot compete with advanced nodes to be the main show, and they cannot compete with China on price. But by finding an irreplaceable position in the AI ecosystem, perhaps mature companies can survive.

Is This a Problem?

Is the collapse of Taiwan’s mature design companies a crisis that must be averted? Depends on who you ask. When speaking to some representatives of advanced design companies, I’ve heard people say that they “want mature designers to die” so that profitable companies can soak up their valuable talent. If this is the case, then perhaps it’s okay for mature designers to dwindle. Maybe Taiwan is simply moving up the supply chain to advanced nodes and leaving the cheaper mature nodes to China.

Of course, mature design companies don’t see it that way. Many are convinced that mature chips must be afforded the same protections as advanced chips. Perhaps it is a national security risk if all our server cooling chips can only be made in China.

If mature chips are just the garnish, then maybe it’s okay for them to fall, as long as we have the steak. But mature chip companies also tend to liken the industry to cars. The car needs its hood and headlights too, not just the flashy engine.

This plight opens new questions for policymakers in the U.S. and Taiwan. Should we be protecting mature chips? If so, how can we protect mature chips? It’s hard to ban based on performance without banning everything under the sun, so policymakers will need to find creative ways to protect the industry.

Tariff-proof Tea

Bryan Cheong is from Singapore, and lives and works on software in San Francisco. You can follow him on X here.

Most of the overseas tea merchants with sources or warehouses based in China that I love have paused their shipments to the United States after the latest tariffs were imposed and the de minimis exemption was struck. But the US has no shortage of tea collectors who have amassed vast stores of aged tea, who found customers even from across the Pacific. Two such collectors are based in the California Bay Area. Probably the second-largest of these belongs to Roy Fong, the founder of the Imperial Tea Court in San Francisco’s Ferry Building, who counts among his stores a 1980s puerh collectionfrom the Menghai Tea Factory, which crossed the border more than 40 years ago and is safe from additional customs and duties. This does not mean that the tea is cheap — aged puerh tea has been prized particularly by the Cantonese in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. Roy Fong had also previously invested heavily in trying to grow tea cultivars in California, but the arid conditions of the state proved a difficult environment for the plants to flourish in. Nevertheless, tea is an adaptable plant, and forcing it to try to grow under new conditions is how we get new cultivars like Taiwan’s high mountain oolong bushes. Fong might have succeeded eventually, but alas, a fire in 2017 destroyed most of his tea plants and a portion of his puerh collection, so California’s aspirations for domestically producing tea will have to wait for another pioneer. Notable among the Imperial Tea Court’s offerings are the Special Reserve Ripe Puerh, available in cake form and loose, which have been collected and stored in California for the last 40 years. Puerh tea is made from the large-leaf variety of the tea plant, and is grown in Yunnan province in China. Yunnan is the ancestral heartland of the wild tea tree, and ripe puerh is an artificially fermented tea that mellows the large and astringent leaves into an earthy plum-coloured brew. The Special Reserve Puerh can be ordered online, but if you are in San Francisco, I invite you to try it in person at the Hong Kong-style teahouse at the Imperial Tea Court. On the nose, it is like dry leaf litter mingled with moss, sprinkled with a dusting of Ceylon cinnamon. On the tongue, it is sweet and clean, its age has mellowed any muddiness or bitterness and turned the tea rich and smooth with mineral undertones, and it does not turn bitter no matter how long you steep it. In the stomach, it is comforting and warming. The leaves will survive many, many steepings.

Soviet Ekranoplans could at most accommodate sea states 2 to 3.

See Ian Easton for details: “PLA materials express a belief that there are only two realistic time windows open for invading Taiwan. The first is from late March to the end of April. The second is from late September to the end of October.”