How Hangzhou Spawned Deepseek and Unitree

No, it's not another silicon valley, it's something different and more interesting

Zilan Qian is a fellow at the Oxford China Policy Lab and an MSc student at the Oxford Internet Institute.

What conditions made DeepSeek possible? Despite widespread debate, much of this discussion remains concentrated at thce macro-level of nation-states or the micro-level of tech companies. In prevailing narratives, DeepSeek is either seen as a symbol of China’s rising technological prowess or a lone disruptor challenging a top-down innovation system. Hangzhou 杭州, the city where DeepSeek is based, rarely takes center stage.

A closer examination of Hangzhou’s emerging tech ecosystem reveals that DeepSeek did not appear by chance. Hangzhou is the home of six other emerging tech companies — nicknamed Hangzhou’s “six little dragons (六小龙)”: Unitree (宇树科技) and Deep Robotics (云深处科技), two of China’s leading robotics companies; Game Science (游戏科学), which produb cced China’s first AAA game Black Myth: Wukong; BrianCo (强脑科技), a brain-machine interface innovator; and Manycore Tech (群核科技), the world’s largest spatial design platform as of 2023. Even earlier, in 2000, the city saw the emergence of the Alibaba Group — now the second largest e-commerce platform in the world and the developer of another leading Chinese AI model (Qwen).

So, how much does geography matter for the emergence of these companies? After DeepSeek made headlines, the media started to name Hangzhou “China’s Silicon Valley [1] [2] [3].” This convenient comparison is often used to imply a zero-sum U.S.-China rivalry, as if Hangzhou is China’s secret AI and robotics hub designed to challenge the Silicon Valley-backed U.S. The label also projects a misleading image of Hangzhou as a hyper-technical, Silicon Valley-style hotspot, which obscures the fundamentally different comparative advantages and strategies at play.

The Missing Ingredients

Silicon Valley has many essential ingredients that Hangzhou lacks. Researchers argue that Silicon Valley's model has six interconnected elements: (1) venture capital, (2) human capital, (3) university-industry ties, (4) direct and indirect government support, (5) industrial structure, and (6) support ecosystem. Compared to Silicon Valley, and even to most tier 1 cities in China, Hangzhou lacks at least four of these elements, with no clear advantages in venture capital, human capital, university-industry ties, or industrial structure.

Firstly, the venture capital system in China has always been weaker than that in the US, and the gap has significantly widened in the past few years. Overseas and domestic VC fundraising for Chinese companies has drastically fallen, with RMB-denominated funds falling from 88.42 billion USD in 2022 to 5.38 billion in 2024, and USD-denominated funds from 17.32 billion to 0.75 billion during the same period. Within China, Hangzhou did not stand out as a recipient, with venture capital investment mainly flowing into Beijing, Shenzhen, and Shanghai from 2000-2022. Although Zhejiang province (which houses Hangzhou) was the biggest recipient of venture capital funding in 2024, this capital poured in only after companies like Game Science and Unitree had already begun to gain national attention. In fact, Zhejiang saw 41 new corporate venture capital funds registered in 2024, the highest among 18 mainland provinces, which highlights how investment responded to, rather than catalyzed, the region’s tech momentum.

Likewise, Hangzhou lags behind not just Silicon Valley but also major Chinese cities in terms of human capital. The city does not have a strong university cluster. Although some would hype up Zhejiang University as China’s Stanford, in reality, Hangzhou’s higher education is not even competitive among other top cities in China. Zhejiang University (ZJU) is the only elite university included in the national 211 project in the whole of Zhejiang province. In comparison, Beijing has 26 such universities, Jiangsu 11, and Shanghai 10. This shortage has broader implications. Although talent can migrate, the lack of top universities also makes a Hangzhou hukou (household registration) less appealing. Due to the provincial nature of China’s university entrance exams, living in a city with prestigious institutions (like Beijing and Shanghai) offers more educational opportunities. That’s because top universities allocate a larger share of admissions quotas to local students. For example, in 2024 Peking University and Tsinghua University recruited 580 out of 68,000 students from Beijing, compared to 380 out of 405,000 from Zhejiang province. The admission rate for Beijing students (0.85%) was 9.5 times that of Zhejiang province (0.09%).

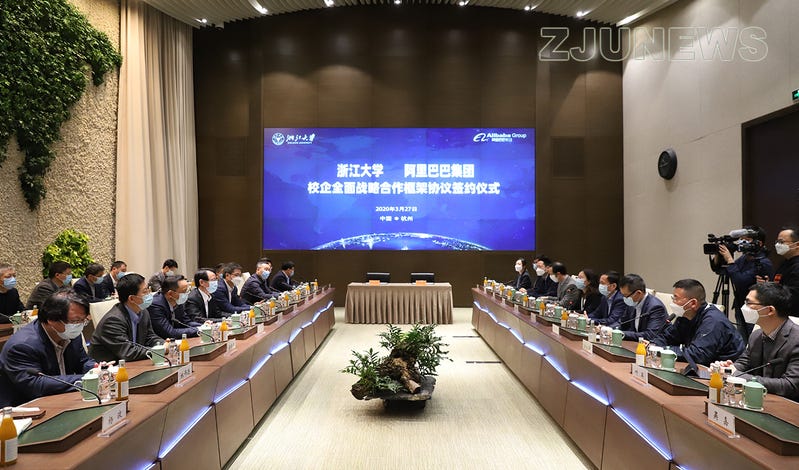

While university-industrial ties do exist in Hangzhou, they are far less rigorous than the “Silicon Valley model.” The few cases of cooperation between ZJU and Alibaba1 are incomparable to the numerous startup accelerators and the wide range of university-industry collaborations offered by Stanford or the University of California, Berkley. Overall, China has relatively weak university-industry ties compared to most prominent research universities in the U.S. Even within China, Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University precede ZJU in terms of unicorn incubation capacity.

Moreover, although almost all founders of the “six little dragons” and Alibaba have ties to universities in Zhejiang, the successful tech companies did not directly spin out from the universities themselves. Liang Wenfeng founded High-Flyer, the hedge fund behind DeepSeek, eight years after graduating from ZJU. Alibaba founder Jack Ma applied and got rejected from 30 different jobs after graduating from Hangzhou Normal University. BrainCo was a spinout from Harvard’s Innovation Lab during the CEO’s postgraduate studies at Harvard, although he completed his undergraduate degree at ZJU. After graduating from Zhejiang Science and Technology University, Wang Xingxing, the founder of Unitree, went to Shanghai for master studies and joined DJI, China’s leading drone company. The distance between these entrepreneurs and their Zhejiang academic backgrounds makes it challenging to prove a causal connection to Zhejiang’s university innovation capacity.

Lastly, unlike Silicon Valley, which developed on a base of the Cold War defense industry, the city does not have a strong industrial history. In 2023, Hangzhou’s industrial gain was 2107.4 billion RMB, 12th among major cities in China and less than half of what Shenzhen (4851.0 billion RMB) made that year. Moreover, Hangzhou’s industrial structure is largely dominated by light industries such as textiles (i.e., Silk) and food & beverages (i.e., the F&B giant Wahaha).

The Special Sauce: Market-Driven Flexible Governance

If Hangzhou can’t compete with Silicon Valley — or even Beijing and Shanghai — on venture capital, elite talent, or deep university-industry ties, then maybe we’ve been asking the wrong question. What if Hangzhou’s strength lies not in what it has, but in how it works with having less? Because Hangzhou doesn’t hold the same political, financial, or industrial significance as China’s top-tier cities, it may have more room to exercise agency at the city and provincial levels in shaping its tech industry and broader innovation ecosystem. This relative autonomy has allowed local officials more space to shape the city’s tech sector and broader innovation environment. Rather than taking a top-down or directive stance, the government has adopted a more service-oriented approach.

Hangzhou fosters a policy environment that actively supports small and micro enterprises, enabled by what Liang Chunxiao of the Pangoal Institute (盘古智库) calls “flexible governance (柔性治理).” In contrast to Silicon Valley’s boom-and-bust cycles that favor survival of the fittest, Hangzhou’s bottom-up orientation encourages experimentation and decentralization, allowing grassroots innovators to flourish without being eclipsed by state-backed giants. Rejecting the traditional image of government as a top-down authority, Hangzhou officials have openly embraced a “waiter” (店小二) and “nanny” (保姆) mentality that positions them as facilitators, not enforcers, in the city’s innovation ecosystem. Unitree once faced an urgent need for systematic protection of its intellectual property rights. In response, Hangzhou promptly rolled out a fast-track patent pre-examination service, sending officials directly to the company to explain the process and offer guidance. Similarly, during the seven years Game Science spent developing Black Myth: Wukong, the local government helped with licensing applications and connected the company with animation studios, and even arranged daily meal deliveries to their cafeteria.

Moreover, Hangzhou’s flexible governance is closely aligned with market principles, making the city especially attractive to a wide range of domestic private enterprises beyond just technology companies. This broader foundation helps explain why a company like DeepSeek, which originated as a spinout from a financial services firm, could emerge and thrive. As Qin Shuo 秦朔, a Chinese business thinker and former CEO of China Business News (CBN), notes, DeepSeek stands out for its market-driven innovation model: rather than depending on state research institutes or tech giants, local firms like DeepSeek have succeeded by identifying unmet market needs and responding swiftly.

This market-oriented environment has deep roots in Zhejiang province’s governance philosophy. As early as the 1980s, during the early phase of China’s economic reforms, Zhejiang — of which Hangzhou is the capital — pioneered efforts to encourage private enterprise and entrepreneurial experimentation. This legacy paved the way for Alibaba’s eventual rise. When Alibaba was founded in the late 1990s, Jack Ma tried but failed to headquarter in Beijing or Shanghai, due to expensive rent and bureaucratic barriers. He later moved the company back to Hangzhou and has received government support since. In 2015, Ma remarked on his decision to headquarter in Hangzhou: “Beijing favors state-owned enterprises, Shanghai prefers foreign companies, and Alibaba (as a domestic private company) was nothing in the eyes of Beijing and Shanghai. If we return to Hangzhou, we become the local only child (独生子女) (who receives all attention and support from parents).”

The success of this “only child” has in turn strengthened the city itself, creating a mutually reinforcing relationship. Beyond e-commerce, Alibaba has provided Hangzhou with vital infrastructure: digital financial services, cloud computing, an ecosystem for entrepreneurship and innovation, and a foundational employer and taxpayer. This ecosystem has laid the foundation for successive waves of tech companies to grow and thrive, reinforcing Hangzhou’s position as a leader in China’s digital economy.

Market-Driven Innovation… with Hangzhou Characteristics

Although the “market-driven” innovation model is generally regarded as a typical U.S. innovation model, Hangzhou’s “market-driven” model is different in that it still maintains a level of centralized governance, rather than relying entirely on market forces and entrepreneurial dynamism. Unlike the government support in Silicon Valley, which sometimes prioritizes tech innovation at the expense of public living conditions, Hangzhou’s government sees quality of life as a critical strategy for attracting companies and talents.

But this governmental support is also different from a stereotypical Chinese “state-driven” innovation model, as the local government positions itself as an enabler, rather than a controller. The lack of state-backed research institute clusters, traditional national champions, and strong industrial foundation contributes to the government’s humble attitude and the desire of private enterprise. If Hangzhou were more strategically important, more industrial, or more academically prominent, DeepSeek might not have had the creative space to emerge.

Is the Hangzhou model replicable in other Chinese cities? When DeepSeek first emerged, local governments and media were frantically seeking the answers to this question. On February 7, Jiangsu province’s official media platform published a three-part series: “Why Did DeepSeek Emerge in Hangzhou?”, “Why Can’t Nanjing [the capital of Jiangsu Province] Produce Its Own ‘Six Little Dragons’?”, and “Hangzhou Has DeepSeek — What Does Nanjing Have?” On February 10, the Jinan government published “What Can Jinan Learn from Hangzhou’s ‘Six Little Dragons’?” And on February 12, Hefei Daily ran a front-page editorial again asking: Hangzhou has DeepSeek — what does Hefei have?

To summarize those reports:

The Jiangsu government concluded that Nanjing companies lack customer sensitivity, which is crucial in sectors like EVs, AI, and e-commerce, but emphasizes that Nanjing firms can benefit from their strong ties to government and industry.

Hefei attributes Hangzhou’s success to its reconfiguration of production factors, which enabled a swift transition from the internet economy to AI. Hefei is pushing to grow sectors like EV, photovoltaics, and biopharma, in part by increasing investment in the province’s prestigious University of Science and Technology of China.

The Jinan government notes its similarity to Hangzhou in terms of pro-innovation policies, but notes that Hangzhou invests beyond national champions and takes a pragmatic, rather than bubble-chasing, approach to tech. Citing Hangzhou’s brain drain and weak regulatory oversight, the report warns against copying innovation models wholesale: “A city's innovation ecosystem requires both passion and cool-headed reflection. When the capital frenzy subsides, only those technologies that truly cross the ‘valley of death’ will endure.”

But the Silicon Valley model is not replicable in every region. As much as one might want to create ChatGPT-like innovations using fixed recipes and ingredients, the kitchens and cookware differ everywhere. Granted, one cannot cook without rice (巧妇难为无米之炊): talent is essential to innovation, just as compute is to training LLMs. But the condiments and methods of cooking vary depending on the kitchen — that is, the political environment — and the amount of staple ingredients like compute, talent, or funding. It makes sense for Silicon Valley to thrive on venture capital and a deep industrial base, just as it makes sense for Hangzhou to develop through its distinctive governmental support. After all, innovation ecosystems aren’t like LLMs that can be ranked through benchmark tests — even benchmark tests are increasingly not reflective of the actual capability and nuances of LLMs.

Tasting the Dish

The most beneficial thing DeepSeek has brought to my life is that it makes introducing where I’m from much easier — especially when “I’m from China” doesn’t satisfy the listener.

“So, where in China?”

Over the years, I’ve tried introducing Hangzhou through various achievements I thought were important: “The city that hosted G20”, “The city with UNESCO sites West Lake, Grand Canal, and Liangzhu City,” or “The city that hosted the Asia Games”. None of these worked better than “a city near Shanghai” until January 2025. Now, I simply say, “The city where DeepSeek is from.”

“Oh,” replied many people, “so it’s like China’s Silicon Valley.”

“No. It is nothing like Silicon Valley.”

Yes, ZJU has an innovation center under its international business school; yes, ZJU does try to credit Deepseek and other Hangzhou tech companies’ success to its “entrepreneurial spirit and innovative thinking”; and yes, Alibaba, China’s largest e-commerce company, does have long-time and diverse collaborations with ZJU on digital healthcare, quantum physics, and other frontier technology.

Listening, and caring seems to be two key elements in Hangzhou's success. Sweet!

"Unlike the government support in Silicon Valley, which sometimes prioritizes tech innovation at the expense of public living conditions, Hangzhou’s government sees quality of life as a critical strategy for attracting companies and talents."

"Hangzhou lacks at least four of these elements, with no clear advantages in venture capital, human capital, university-industry ties, or industrial structure"... Please, you should check on this. Have you heard about Zhejiang University, N3 of China and N1 in overall budget? Precisely, ZJU has developed a model of building specific ecosystems with the tech, medical, space, and other key industrial sectors. These ecosystems are linked to banks and massive donors (like Alibaba) that have developed huge incubators for start-ups like DeepSeek. Anyway, great piece, catching some of Hangzhou essence and incomparable charm.