Xi and Putin Weaponize WWII's Legacy

From Joseph Torigian

A guest post by Joseph Torigian Professor at American University as well as the author of the new Xi Zhongxun biography and a book exploring succession politics in the USSR and CCP.

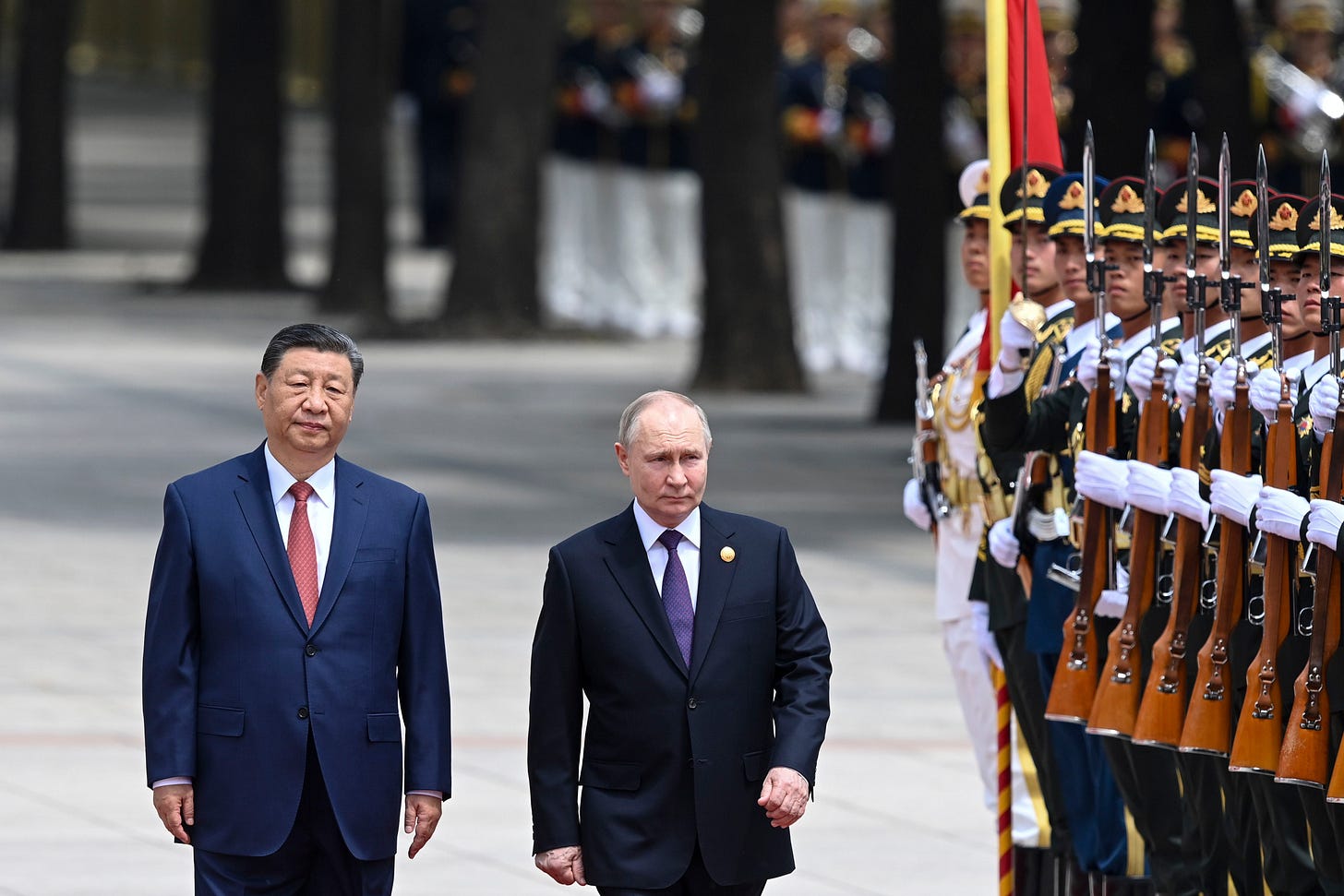

September 3 will mark the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II, and Xi Jinping will host Vladimir Putin in Beijing for a military parade to mark the occasion. For both men, it will be an opportunity to assert the civilizational agendas they are pursuing.

Xi and Putin see themselves as men who inherited a baton from their forefathers to continue a struggle against outside enemy forces who have always wanted to eliminate their countries’ distinct national characteristics and subjugate them.

For both, the war was personal. During World War II, Xi’s revolutionary father Zhongxun concentrated his energies against the Nationalists and was never near Japanese forces. Yet Jinping’s mother Qi Xin personally witnessed the Japanese seizure of Beijing, was nearly killed by enemy cavalry, and witnessed atrocities committed by imperial forces. Xi Jinping even lost a first cousin, only an infant, to the fires of war.

Putin’s family also suffered. His father was severely wounded in combat against the Nazis and survived the Siege of Leningrad, where an elder brother died. His maternal grandmother was slain by Nazi occupiers.

For both Xi and Putin, victory then was costly, but incomplete. Although the war concluded before they were born, it resonates with them differently from other contemporary world leaders. Xi and Putin believe that “hegemonic forces” still want to impose a foreign model upon them and block their rightful place in the world. Now, they want to use the memory of the war to inoculate future generations against Western values and legitimate the global order they envision.

Having witnessed the chaos their nations faced for much of the twentieth century, both are deeply preoccupied with the question of political order. Xi Jinping was incarcerated and exiled during the Cultural Revolution and feared state collapse during the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. Vladimir Putin famously saw the collapse of Soviet power in East Germany as a young KGB officer. Both Xi and Putin believe that their rise to power stopped centrifugal forces, supported by the West, that threatened to tear their nations apart before they came to power.

Commemorating World War II serves that mission. Both men clearly believe that their nations need a sense of idealism, sacrifice, and commitment to survive. History as moral education is a powerful tool for that purpose. World War II was a moment that showed their nations could achieve extraordinary victories.

Xi and Putin see the suffering their peoples experienced as something that deserves only the most profound respect both at home and abroad. The anniversary has been turned into an instrument to instill loyalty to the state among a younger generation. That message is especially significant for their militaries, as Russia continues its war against Ukraine and China prepares the People’s Liberation Army for a possible war on Taiwan.

It is also a time to remind the outside world what China and Russia think they deserve as major contributors to victory in World War II. At the war’s end, both nations were recognized as major powers. For Putin, Yalta meant Russia was given special rights in its so-called “near abroad.” For Xi, the defeat of Japan meant Taiwan should rightfully return to the Chinese mainland. Beijing and Moscow see American activities in their neighborhoods as a return to the power politics that led to war decades ago.

That is why Xi and Putin obsess over a perceived grievance that diminishes the contributions of the countries' role in the war. Control over history is literally a matter of regime security and strategic imperatives.

The Chinese Communist Party opposes any attempts to deny the Nanjing Massacre and the horrific biological and chemical warfare experiments on human beings at Unit 731 in Manchuria. Two movies, one on each of those topics, are being released this year in China. The party also opposes the largely accurate narrative that the communists sat out much of the war against the Japanese.

In Russia, former Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky used the words “human scum” to refer to anyone who debunked the legend of Panfilov's Twenty-Eight Guardsmen, who allegedly all died fighting off the Nazis outside Moscow.

Yet questions remain about the long-term efforts by Xi and Putin to immortalize their regimes and their use of the memory of World War II for that purpose. The story of Chinese and Russian history is often one of unintended consequences. Mao Zedong launched his Cultural Revolution to prevent capitalism from appearing in China. It was such a disaster it triggered Reform and Opening. Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempt to save the Soviet Union destroyed it.

Putin sees the war against Ukraine as a sort of sequel to World War II that can help him recast another generation of Russians according to his vision. He sneered as young people fled the country to avoid the draft, describing them as “scum and traitors” that Russians would “simply spit out” “like a gnat that accidentally flew into their mouths.” He seeks to politically empower veterans – for instance through his Time of Heroes program to get them elected on his party’s ticket. Patriotic education has contributed to the militarization of society. The economy is now hardened against sanctions and geared to fight a long-term war. Yet what will Russia do without its most talented young people if they flee or die on the battlefield? Will Russians become exhausted by the war? And how long can prolonged competition with the West last with an economy whose future has been mortgaged on the war?

Xi can only use the memory of war and the possibility of potential war in the future. He uses the revolutionary legacy, of which the war against Japan was a part, to achieve what he calls “self-revolution.” It is a call to vigilance, a call to “eat bitterness,” a call to yet another young generation of Chinese to devote their lives not just to themselves but also to national rejuvenation. Yet Xi does not want his relationship with the West to go completely off the rails. Unlike Putin, he wants to benefit from economic, financial, and technological ties while he can. The question is whether Xi can achieve both struggle and pragmatism at the same time.

As for the international community, the commemoration in Beijing will likely not fundamentally change any feelings in the West towards Russia or China. No Western nation is convinced that the Ukrainians are Nazis, as Putin falsely alleges. And although China has sought to avoid economic and reputational costs, it has unambiguously been a major facilitator of Russia’s war machine. The military parade, along with the recent treatment of Japanese citizens and military exercises around Taiwan, might frighten China’s neighbors more than win them over with the memory of China’s role in the defeat of Imperial Japan.

No historian can deny the contributions of China and Russia in the defeat of fascism in World War II. But the war’s role in justifying authoritarianism at home and expansion abroad is not a tribute that will inspire everyone.

For more with Joseph Torigian, check out our podcast on his first book on CCP power struggles.

Elite CCP Power Struggles

Joseph Torigian’s Prestige, Manipulation, and Coercion: Elite Power Struggles in The Soviet Union and China After Stalin and Mao is one of my favorite China books. Books that deeply engage with both Soviet and CCP primary sources around elite politics basically never come out nowadays.

And the two-part five hour epic we did covering his monumental biography of Xi Zhongxun.

Xi's Father

Joseph Torigian’s The Party’s Interest Comes First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping is a monumental scholarly achievement — easily a contender for one of the best China books of the decade. Joseph’s goal, in his own words, was to “shine as much light into the darkness of the past as possible” to understand the nature of authoritarian polit…

Xi Zhongxun’s Second Act

This is part two of our series with Joseph Torigian, author of the definitive biography of Xi Zhongxun. This episode traces the inner world of a man navigating power politics, exile, and reform, and the legacy he left his son, Xi Jinping.

This was insightful beyond all the news about the military parade

Excellent insight. Thanks 🙏.