Reading Abundance from China

Highlights from a Mandarin discussion group

afra is the author of the Concurrent Substack and host of the CyberPink podcast. Concurrent explores the parallel and colliding tech and cultural currents shaping Silicon Valley, China, and beyond. Her show 疲惫娇娃 CyberPink is a Chinese-language podcast about popular culture. From screens to the cosmos, it explores culture in its broadest sense—using women’s voices to expand the ways we engage with and imagine the world. It is very good I highly recommend!

I recently hosted a 2-session reading club for Abundance, bringing together paid subscribers of my Chinese-language podcast CyberPink and those of our sibling podcast American Roulette. Ours was conducted entirely in Mandarin Chinese, which meant that the participants, by default, were like me: born and raised in China, educated in the West, and now navigating the cultural and ideological fault lines between the two. Among the attendees were academics, lawyers, consultants, AI investors in Silicon Valley, and engineers in big tech.

When you discuss American politics in a group like this, perspectives shift constantly. As we dissected Abundance, we toggled between the imagined readers in Brooklyn, the Bay Area, and D.C., and a more distant, more foreign vantage point — one grounded in the trajectories of China itself. In short, we examine the U.S. as foreigners, as immigrants, as Chinese.

Somewhere along the way, our Signal group of book club organizers — my podcast co-hosts and friends — jokingly named the group *Ezra Thought Study Group* (Ezra思想学习小组), a parody of Maoist-era “Marxism Study Group” or more recent “Xi Jinping Thought Study Group.” It was tongue-in-cheek, of course, but it also captured something real: we all sensed that this book was both a techno-optimistic manifesto from central-left, and a piece of strong political persuasion to the reconfiguring Democratic Party.

In this article, I’ve selected fragments from the 100-page (!) transcript of two book clubs, each lasting 1.5 hours — but not the ones you’ve probably heard before. I’ve deliberately cut the standard U.S.-centric book analysis and policy talks; this article is some curated moments that I believe offer some fresh takes. Consider this: Reading Abundance from China.

Note:

The book club followed the Chatham House Rule: participants may use information from the meeting but cannot reveal speakers' identities or information sources. However, I received permission to include some speakers' names and occupations. I've tried to maintain the conversational rawness and haven't done extensive editing, so the transcript may contain factual mistakes. If you find any, please leave a comment. The transcript has been translated and made readable by Claude.

The poverty of American imagination:

Lokin (Lawyer, lives in NYC): I think there's this incredibly limited imagination about what the "good life" looks like in American culture—both among ordinary people and political elites. And this limitation becomes a huge obstacle to building a more abundant, more public, more sustainable future.

There's this perfect example: a Democratic delegation visited Japan recently, and several congresspeople toured the Shinkansen—which, by the way, was built in the 1960s with American funding.1 What's almost laughable is that even today, this public transportation system—which isn't exactly cutting-edge anymore—still managed to "shock" American congresspeople. This tells you that even the highest-ranking political elites don't really have opportunities to experience or understand the kinds of lifestyles other countries have built.

More broadly, American society's vision of lifestyle is still heavily dependent on this outdated American Dream: everyone should own a detached house with a front and back yard, white picket fence, and one or even multiple cars of their own. This individualized, anti-public understanding of the "good life" makes it hard for people to imagine, let alone accept, lifestyles based on public transit, shared spaces, and urban density. So we can understand why American rail infrastructure always struggles to move forward—it's not just technical and budget issues, it's cultural and imaginative barriers.

I was talking to a professor at Columbia—one who’s knowledgeable, well-traveled, worldly person. He told me how impressed he was by Beijing's public safety: at 1 AM, he saw a woman in fur and jewelry walking alone on the street, eventually taking the subway home without any worry. He cited this as positive evidence of modern urban life.

I politely reminded him: if you want to use an example to illustrate good urban safety, you should really mention Tokyo or Seoul instead. Because these cities are equally safe, but they're less likely to be misunderstood as depending on "authoritarian order" for maintenance. When you use Beijing as an example, in the American context, it easily activates this "authoritarian scratch"— people who are culturally inclined to believe order can only be achieved through strongman rule will instinctively equate urban safety with authoritarian governance. They'll think only highly centralized power systems can achieve clean, safe, orderly urban life. This imagination further reinforces their pessimism about democratic countries' inability to govern cities well, providing psychological support for rationalizing some kind of authoritarian governance logic.

But this is actually a very dangerous misreading. We have to dismantle this binary thinking: cities can be both safe and free; public life can be both efficient and democratic. This kind of life exists not only in Tokyo, Seoul, Amsterdam, Zurich, but could absolutely be realized in America, provided we first culturally change our assumptions about what "ideal life" looks like.

What's even more concerning is that even these elite intellectuals still lack basic concepts of what "modern urban life" should look like. They may have never truly internalized the daily experience of "stepping out and taking clean, safe subway, walking freely in dense urban neighborhoods." They still view "cities" as dirty, dangerous, anxiety-inducing places, while treating "suburbs" as safe, clean, ideal residential areas.

This deeply rooted cultural cognitive structure is the biggest resistance we face when promoting public lifestyle transformation. Under this cultural logic, even with sufficient resources and mature technology, it's hard to push for truly progressive infrastructure transformation.

Afra: The poverty of American elite imagination about "happy life" is a key factor preventing visions like Abundance from being realized. Even if we set aside structural obstacles like racial discrimination and economic interests, just looking at popular culture, America’s deeply influential soft power, the society has already fallen into a kind of imaginative local optimization.

As the world's most powerful popular culture exporter, Hollywood has long been continuously and repeatedly producing a specific kind of life picture, and this picture's singularity is actually quietly limiting public understanding and imagination of the possibilities for abundance and "good life."

For example, when Hollywood wants to show a big city's bustling scene, the template is almost always New York: broken-down subways full of rats, Manhattan's towering skyscrapers, a city that's vibrant yet dirty and chaotic. This "city equals anxiety" narrative has almost become American culture's default setting.

And when film and TV want to imagine "ideal life," the camera often turns to suburbs: spacious detached houses, white fences around front yards, two cars, a few dogs, quiet tree-lined neighborhoods, and a typical nuclear family. This repeatedly reinforced template creates a ceiling for cultural imagination, making it hard for people to conceive of a lifestyle that's both urban and livable, both public and high-quality.

It's precisely this imaginative pathway that's been constantly reproduced by the cultural industry for years that makes "abundance" futures largely misunderstood as extensions of consumerism or "upgraded versions of suburban dreams," rather than optimization of public spaces, infrastructure innovation, or reorganization of human relationships.

On environmental assessment in China and the US

T, (Economist): I'm an economist, and my main research area is causal inference. Right now, most of our policy evaluations are built on causal inference methods. The most common example would be A/B testing or randomized controlled experiments. Many policy evaluation paradigms, including things like environmental assessment, basically follow this same logic and process—they're all built on this scientific framework about what makes policy "rational."

But the problem is, this approach might be missing a crucial point: when we do A/B testing, we often can't capture general equilibrium effects. We don't have the ability to properly measure the chain reactions that policies create at the system level. What we get is often just a local impact—a primary feedback observed under specific settings. But this local effect might not be the most important first-order effect; the deeper structural impacts might be exactly what gets excluded because our evaluation methods are too reductive.

I think environmental assessment is a perfect example of being shaped by this paradigm. Many countries do environmental assessments—China has similar systems too. But China's environmental assessment often feels more like formalistic copying: seeing that the U.S. and other countries have environmental assessment mechanisms, so we "should" have them too. But for a long time, China's environmental assessment wasn't treated as a serious, scientific problem, so it didn't adopt the kind of rigorous processes based on scientific methods like America does.

The result is that in China, environmental assessment plays a very limited actual role in infrastructure development. And in America, while the environmental assessment system itself is more influential, the methods it relies on still tend to only capture partial effects while ignoring broader general effects. For example, opportunity cost might be a crucial variable in policy choices, but it's not something that's easily captured in our current mainstream operational inference frameworks.

So I think there's this really interesting, even ironic paradox here: our methodology is indeed getting more and more advanced, allowing us to make increasingly "scientific" policy evaluations. But at the same time, it's precisely these methods themselves that are making our understanding of the complex, multi-layered impacts after policy implementation more narrow. Maybe in trying to make policy evaluation more "falsifiable" and more "rigorous," we're also losing our sense of its holistic and long-term dimensions.

The "tech OS gap" between China and the US

Du Lei (tech investor, lives in the Bay Area): From my background—I originally did AI research and now I'm in tech investing—so I instinctively tend to look at problems from a "system design" perspective. My very intuitive feeling right now is: America is using an outdated institutional framework, this old governance "software," to deal with a real-world social system that has higher bandwidth, more complexity, and faster change. The result is—the whole system is starting to fall behind.

The deregulation that Abundance mentions frequently, in the short term, might indeed be an emergency measure to improve efficiency. But if it's just deregulation without actually rebuilding this institutional infrastructure, it's probably just "treating the head when the head hurts, treating the foot when the foot hurts."

It's like a programmer who just joined a company that's been using a ten-year-old system, saying: "This legacy code is too messy, just delete it." Deletion might feel good, but three months later the whole system could just crash.

Let me talk about the differences between China and America. I think China's execution advantage in certain areas doesn't necessarily come from so-called systemic superiority, but is more like a manifestation of a technological generation gap.

At the end of the day, China's bureaucratic system is more updated than America's. So even if both countries are equally bureaucratic, Chinese government departments use WeChat to communicate directives and share spreadsheets—at least at the tool level, it's faster and more efficient than America's approach which still relies on email and paper processes.

Of course, China has its own systemic problems too. Like this "layer-by-layer responsibility implementation" approach we've seen since SARS, all these "red line" administrative mechanisms often cause inefficiency and even suppress genuine local feedback. But from an operating system perspective, China is indeed faster at "hardware updates," even if the "software logic" still has plenty of problems.

I also want to respond to this topic about "industrial planning vs. basic research." My personal view is: I don't really believe the government can actually push forward much substantive breakthrough in "basic scientific research."

In another book our CyberPink listener’s community is co-reading, Nexus, it talks about how many real scientific breakthroughs actually come from a broad peer network—they need free, open exchange and sufficient resources. So a lot of times, the technological explosions we see are actually the result of long-term, multi-path, slow accumulation.

For example, America's AI explosion didn't just appear one day with a "lightbulb moment," but is the result of twenty years of big data accumulation, gamers pushing GPU performance, miners driving computational power—all these things stacking up over a long time.

It's the same on China's side. A lot of the technological progress we see isn't some policy suddenly deciding something, but the entire manufacturing system, craftsmanship system accumulating through massive iteration processes.

This is a kind of compound advantage. I think we can't misread this compound progress as achievements brought by "government systems." It's more the result of an ecosystem.

The economic-political split: ground-level contradictions in the U.S.

Amber (Consultant, lives in New York): Hi everyone, I'm Amber. When Afra mentioned America "wanting to catch up" or "wanting to lead" in areas like batteries and solar energy, I really resonated with that—there's this complex emotion behind it, both envy and a deep sense of being torn apart.

Let me give you some background. My day-to-day work involves directly dealing with local governments across America, investment promotion departments, including some global investment projects landing in the U.S. Many of the projects I handle involve building factories, offices, job creation, and so on. And in this process, I've observed a very obvious contradiction:

On one hand, local governments desperately want these investment projects to land because they bring tax revenue, jobs, can revitalize their communities and drive regional development. But on the other hand, they're extremely cautious, especially when facing investments from China—political agenda almost always gets put first.

Here's a simple example: it's not just Texas or those Southern states everyone's familiar with—even states like Southern conservative states and Midwest states that seem like swing states are now very sensitive about "Chinese property ownership." Many local governments explicitly write in their RFP documents that they won't accept investments from China—they just completely won't entertain it. For many of the projects we're working on, this is like a blow to the head.

What's more ironic is that many local officials are actually very conflicted privately: they really do want these projects to land, they know these projects are good for the local economy, but they can't help it because the governor, state legislature, and voter pressure require them to "stay aligned with Trump" politically, they have to put on a tough stance. So the whole system is full of internal tension.

And it's the same on China's side. Many Chinese investors really want to enter the American market, they see opportunities, but they just can't get in.

So what we're seeing now is this bidirectional tear: America and China are mutually wary at the policy level, mutually hostile in public opinion, but economically, they both want to get a piece of the pie from each other. America is worried about leaks on one side and unwilling to give benefits, but on the other side wants to take China's money; China is the same—worried about technology blockades on one side, but hoping to get American subsidies and market access on the other.

So on the surface, both sides seem "calm," but privately, the ground-level exchanges are full of struggle and distrust, like a relationship being pulled in two different directions.

This is also the most real state I've experienced when dealing with American local governments, especially some small-town industrial parks: they really are desperate for development on one hand, but on the other hand they're completely constrained by the upper-level political environment, stuck between a rock and a hard place.

The US and China spend too much time doomscrolling on each other’s social feeds

Yiting (tech worker, lives in London): I think China and America right now are exactly like two doomscrollers brainrotting on each other's social media feeds.

It's like America suddenly scrolls through China's feed, sees some superficially shiny stuff, and goes: "Oh? I want that too!" But they don't really understand what this "person" China is actually like—what reality they're facing, what their situation is, what their resources and challenges are. They don't care, and they don't understand. They just see a filtered photo and start envying, imitating, even getting anxious.

Then America's own actions start getting distorted, wanting to "become another person," without figuring out why that other person is the way they are.

Actually, China does the same thing to America.

Many Chinese people, maybe even including some people at the policy level, don't really understand America's political ecology, social structure, or how their institutions actually work. But they scroll through America's social feed—like some very free, very advanced, very prosperous moments—and think: "I want to be like that too."

So the end result is: both sides are looking at each other's highlight reels while ignoring each other's complex realities, and they both fall into this illusion of "everyone else is living better than me."

At the end of the day, I think both China and America should probably spend less time brainrot.

The blind spot of China envy

Luke (tech worker, lives in NYC): I want to ask a direct question—have you guys listened to the latest episode of Bumingbai podcast?2 They mentioned some huge problems behind China's prosperity. I'm particularly curious: if it's people like Derek Thompson or those centrist liberals, in their process of "rediscovering China," after learning about these problems, what kind of reaction would they have? How do they view these realities?

H (media professional, lives in NYC): Personally, I feel like they don't really understand China—many of them haven't even been to China. When they mention China in articles or podcasts, it's not because they really care about China's history, policies, or the situation of its people. They're using China as a mirror or reference point—not exactly a cautionary tale, and not a positive example either, but a contrast that can inspire Americans' imagination, fighting spirit, and policy action.

What you just mentioned, like solar panels—I'm not an expert in this field, but from some reporting and observations, China's rise in this industry did go through a complex process: from early government subsidies and factory expansion to gradually establishing a globally leading position. But in this process, many Western observers ignored the real costs behind it, like compressed labor rights, serious resource waste, and even corruption and benefit transfers. These realities, as people with Chinese backgrounds, we should of course pay attention to, but in the discourse of people like Ezra Klein or Derek Thompson, these are hardly mentioned. What they care more about is how to use "China's success" to inspire competitive consciousness within America.

When they talk about China-U.S. relations, they easily apply the Cold War framework, like comparing it to the Soviet Union's Sputnik moment: the Soviets launched the first satellite, which inspired America's systematic investment in space, education, research, and other fields. This kind of "being inspired" is the process they hope to replicate from China again. But whether this path is correct is itself a controversial political judgment.

Afra: I agree. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson are, after all, American political commentators working within that context. When Ezra Klein mentioned in his podcast that he went to China once about a decade ago, he mentioned that he was talking about having a lot of meetings with officials, with economists, with some business people. So naturally, his China experience draws from that particular slice of the country.

When H mentioned the lithium battery industry earlier, I also remembered chatting with a British scholar a few days ago. She said she attended an academic conference where a young female scholar shared her research on the environmental impact of a lithium battery factory in Sichuan or Anhui (I couldn’t recall). After this young scholar finished speaking, she told all the attendees: "I really hope this paper can be published in China, but I know it's almost impossible." This exposes a core problem: many environmental and industrial costs in China cannot be openly discussed.

A few months ago, I also read an article in Rest of World by Viola Zhou about Chinese lithium battery company Gotion wanting to invest in building a factory in a small Michigan town, bringing huge funding and job opportunities. But the project was ultimately blocked by small-town politics and strong opposition from local residents, where the main resistance was exactly concerns about environmental pollution. In contrast, in China we can hardly truly see these local costs of EV manufacturing or lithium battery factories—exactly how much wastewater was discharged, how much land was occupied, how many people's lives were affected. Much of this data is unknowable because of media lack of transparency and the absence of civil society, meaning these voices have no channels to be heard at all.

H (media professional, lives in NYC): Right, these American "China-envy" people only see the results, like Chinese electric car companies like BYD rising in the global market. But they often ignore the real problems behind these companies, like product quality issues, defaulting on supplier payments, and so on. These more detailed, more complex layers—they don't really care about them.

Debate about the secret sauce and manufacturing mobility

Afra: Ezra Klein mentioned, “the re-emergence of industrial policy in America is 100% about China. Take China out of the equation, and there is no re-emergence of American industrial policy.” Actually, going back to this American reindustrialization thing. Manufacturing: When you really interrogate what technology in manufacturing actually is, of course, you can say part of it is about patents, about things that can be written down, about hard knowledge in manufacturing.

But there's actually another huge part that's tacit knowledge.3 How do you manufacture an iPhone? You need many skilled workers going through many complete assembly lines to put this iPhone together. It's not like you can write the iPhone assembly steps in a piece of paper, and then have new American workers read that paper and immediately go into the factory and start working.

If America needs to reindustrialize, you might really still need to bring Chinese workers back to continue training American workers before you'd have a relatively effective production process. Is America's imagination about reindustrializing very arrogant? Massively ignoring this kind of tacit knowledge in manufacturing and China's accumulated experienced workforce.

X (ML engineer, lives in NY): I have a pretty different, pretty opposite view, because manufacturing itself has extremely high mobility. The reason it exists, the biggest reason it can scale, is that it can reproduce very quickly—the entire factory, the entire process, assembly lines can reproduce very quickly following a template. This is the essence of manufacturing.

At least we might see individual cases like Huawei in the news being a bit less common, or things like that Cao Dewang factory in America having trouble getting started being less common, but including—I don't know if that CyberPink listener is here today, he works in chip industry landing in America—this stuff being able to flow back is the norm.

Manufacturing being able to flow between countries, building a factory and being able to make stuff—this being possible in most cases is actually the norm. If this wasn't the norm, globalization wouldn't have happened. Shenzhen, I think, does have a very unique ecosystem, including its concentration of talent and concentration of knowledge and the existence of the entire ecosystem. I think Shenzhen is a unicorn, just like Silicon Valley itself is a unicorn. But I don't really agree with what you just said about treating manufacturing as something that needs secret sauce, because the essence of manufacturing itself is that it can land anywhere and you can follow the recipe to make it, because if this wasn't possible, this industry wouldn't exist.

So including why everyone in manufacturing, all people in the manufacturing industry, always have this strong sense of crisis about manufacturing mobility—it's still because its mobility is too strong. Including that article I posted before about India, about that piece Viola wrote about India, I found that article very familiar because all the problems they were discussing—Indians feeling like our Indian manufacturing will never get off the ground—but the problems they cited are exactly the same as what I think Chinese people said 20 years ago about how our Chinese high-end manufacturing will never get off the ground.

So I think many things aren't inevitable—it's the current state produced by globalization at this moment. And including my overall view—because I might have followed a few cases at work where a chip factory was moved over from start to finish—I think everyone's degree of exaggerating the secret sauce of many industries is still a bit much.

Afra: What I actually want to say isn't that China now has high-end manufacturing secret sauce that other countries don't have, but that I think this secret sauce cultivation is a very long process. And the reason China was able to cultivate this secret sauce is because China was in a situation at that time—early 2000s, late 90s—where everyone was sharing secret sauce without reservation in a very radical and idealistic state of globalization. But now in 2025, it's no longer that kind of state. Of course, I feel like secret sauce is a very inappropriate term—I'd rather use the term tacit knowledge.

Back in the early 2000s, if China's Foxconn built factories in China, Apple could send large teams of technical bureaucrats to help China build factories and educate the workers. But now if India builds factories saying they want to replace China in manufacturing iPhones, if they want to ask China for some high-end manufacturing help, China definitely say no, because globalization now is not the same as globalization back then. Everyone knows this tacit knowledge is very precious, everyone thinks this is to some degree a huge asset.

X (ML engineer, lives in NY): I think whether they give it or not depends on who's paying—that's also part of the... Back then I think Koreans weren't that willing to give us (China) technology either, but this thing... I think we're all old enough to remember China's manufacturing going from nothing to something, so I'm also very worried that it going from something to nothing is also something we could witness in our not-very-long lifetimes.

Afra: I'm not saying this transition won't happen, but what I quite agree with in Abundance is "America forgot how to build." I think that's a very precise statement, because in manufacturing, knowing how to build and deploy is a "practice makes perfect" technical skill. It's a state that needs more than a lab, more than a book. Just like if you don't exercise for a long time, your muscles gradually atrophy—America's manufacturing muscle has atrophied for decades.

The Deploy chapter in Abundance talks about the lithium battery case, which is really exactly about Americans inventing lithium battery technology and then forgetting how to deploy and scale. Now Chinese lithium battery manufacturers can compress prices in every single link to the lowest, optimize every aspect and every raw material of lithium batteries to the optimal state—this deployment optimization has gone through twenty years. If suddenly tomorrow a Silicon Valley company appeared saying: we're going to build a lithium battery factory from scratch without relying on Shenzhen to teach us, I don't believe it would immediately succeed.

Bay Area’s military-industrial startup renaissance, and China’s "crossing the river by feeling the American stones" innovation style

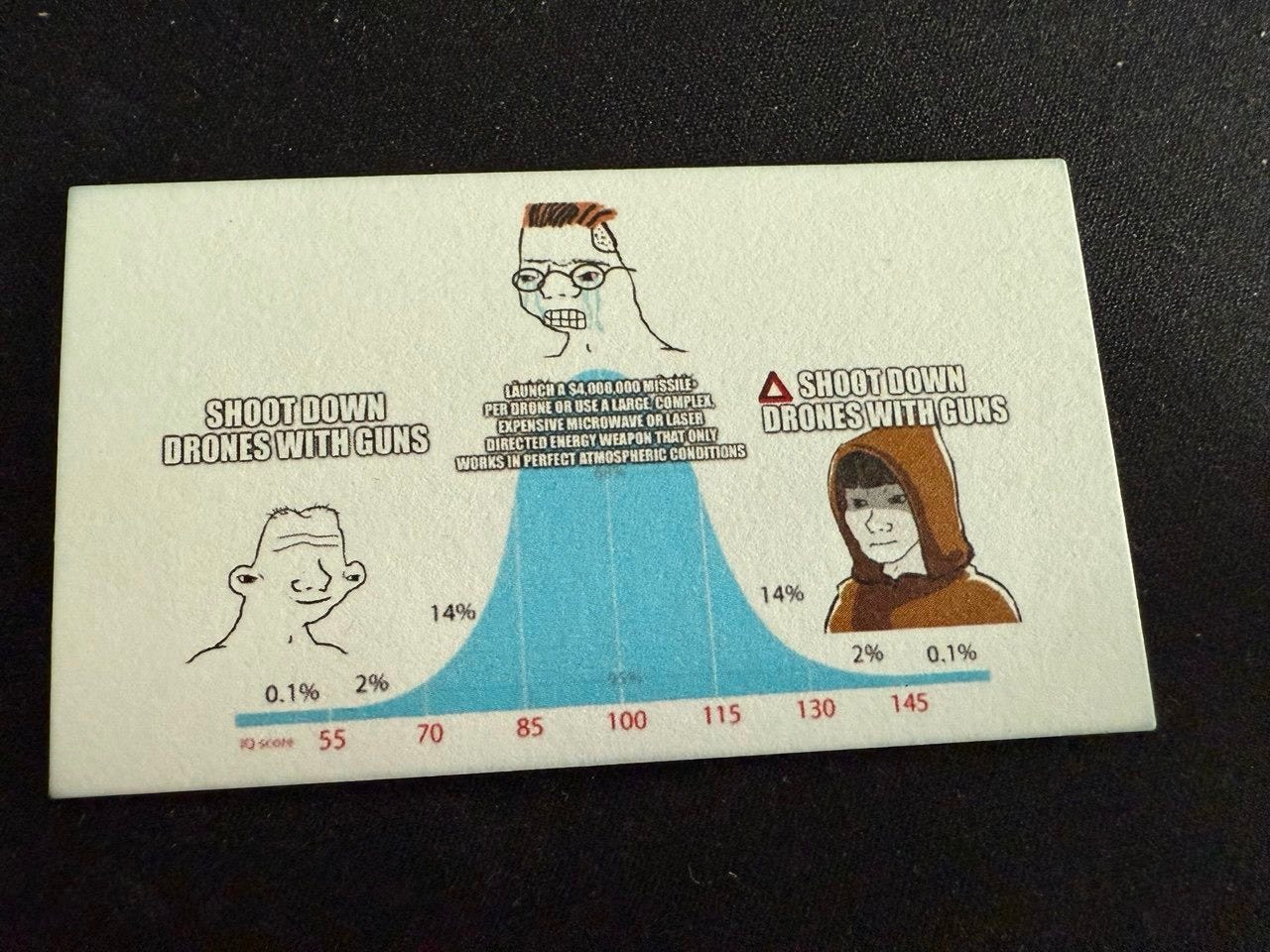

Du Lei (tech investor, lives in the Bay Area): When we think about San Francisco startups, we traditionally picture a software-dominated entrepreneurial ecosystem. But if you head down to the South Bay, there's still this atmosphere tied to traditional industry—especially over the past decade, we've seen the emergence of a whole batch of defense-related startups in America.

Companies like Anduril represent this trend. People are starting to realize that in this new phase of industrialization, defense startups can actually attract venture capital funding, and their returns and growth potential look pretty damn good. So we're seeing that in America, entrepreneurship isn't just limited to crypto or AI—even defense is becoming a new direction that VCs are paying attention to.

I just shared an image in our Zoom chat, it's the business card of a CEO from a startup that makes anti-drone defense systems. You can see a perfect example here: Reddit-style geek culture meeting the defense industry. This seemingly awkward fusion actually shows that America isn't completely hopeless when it comes to rebuilding its manufacturing and industrial base.

At the same time, fields like blockchain and robotics are gradually recovering too.

This highlights a fundamental difference between the innovation ecosystems on both sides. In America, the entire industrial structure and institutional environment is more encouraging of disruptive innovation. Entrepreneurs are more inclined to do things that are completely different, trying to solve old problems with entirely new approaches. Once this kind of innovation gets market validation, it can quickly attract massive capital, and America's institutional and capital mechanisms can give successful players decent returns.

In contrast, truly disruptive innovation is relatively more difficult in China. The path dependency is stronger—a lot of times it's still "crossing the river by feeling America"4, so incremental innovation is more common. This incremental approach actually has strong advantages, especially in large-scale industrial production industries. As mentioned in Abundance, much of real technological progress often doesn't come from some genius's "eureka moment," but from countless small iterations on the production floor, on the assembly line.

America definitely has advantages in excavating "innovation points" that have clear commercial value and market acceptance, but when it comes to those "1.1 improvements"—the continuous polishing and optimization—the gap compared to China is obvious. This actually reflects deep institutional design differences between the two countries: America's system encourages high-risk, high-reward winner-takes-all, while China's structure tends more toward stable returns and inclusive distribution. These institutional and cultural differences in risk appetite ultimately show up in the industrial realities and innovation models we see today.

X (ML engineer, lives in NY): I've been thinking about the past few years, and maybe as someone in the healthcare industry—at least from my own perspective—I actually feel like the reasons why these two countries can't achieve disruptive innovation in certain areas are quite similar: whoever's figuring out how to make money off the government, whoever's trying to optimize the bureaucracy, they can't do disruptive innovation.

The ones who can leapfrog across barriers, especially recently I've been reading Careless People. I've found that whoever can cleverly circumvent regulation, taking action before regulators even react, they're more likely to succeed. This viewpoint might sound a bit cliché, but that's really the situation now.

I think many industries in both China and the US are the same—they're all trying to figure out how to capture more government funding. These industries, as we just touched on, have fallen into a state of false innovation. Just like we discussed in our last book club, they're addicted to surface-level innovation, with all costs going into the bureaucracy. The people who can actually focus on innovation, focus on coding, are really few and far between, and these programmers spend every day in meetings.

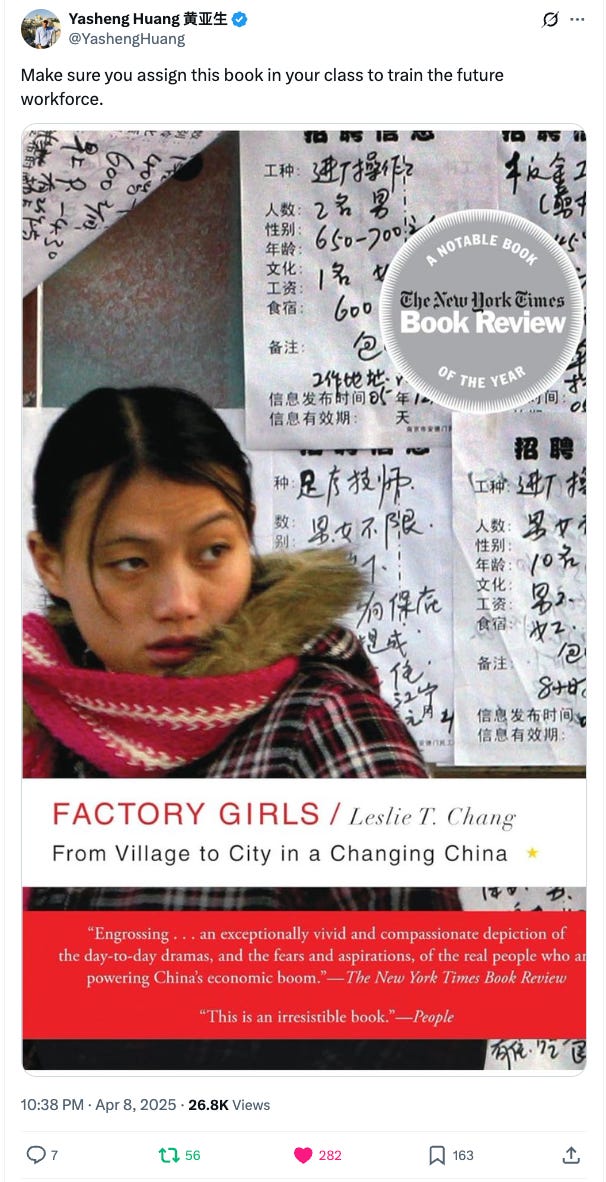

The hidden costs of re-industrialization: the Factory Girls nobody talks about;

Afra: Before the book club ends, let me add one more thing about American re-industrialization. Remember during that period when Trump and J.D. Vance were heavily promoting "American re-industrialization"—there were tons of memes on X. Professor Huang Yasheng from MIT posted a trolling tweet.

Huang Yasheng was basically suggesting that this book tells you some reality about manufacturing and re-industrialization. that you wouldn’t learn in the schools in the U.S. I found that tweet fascinating, so I tracked down the book, which I had heard about for many years, and read it. Many scenes in the book are shocking. Not just because they made me remember that institutionally chaotic China from over 20 years ago, but because they made me rethink the lived reality of ordinary workers under the factory system. The book spends extensive pages describing the real conditions of young female workers on assembly lines.

For instance, in the factories, many female workers (almost all come from rural areas) wouldn't tell their coworkers their real names. Because once you reveal your name, if you happen to run into someone from your hometown, information might get back home, and relatives—even parents—might find out about their income, leading to economic exploitation, with wages being demanded and controlled. These female workers were doing shift work day after day on assembly lines, twelve hours a day, while also facing "exploitation" from their families of origin. The book also describes how they struggled to establish their own identity in extremely compressed living spaces—in factory dormitories with no privacy, living in rooms with six or eight other female workers, where even just trying to make yourself "different from others" was difficult. There was no mobility, no prosperity. It was this state of people struggling to survive within the system, under the assembly line, within silent norms.

After reading this book, I went online to look up what Foxconn factories look like today. I was surprised to find that photos, videos, and even content shared by workers on platforms like Xiaohongshu that circulate on the Chinese internet really aren't that different from the lives of that generation of Shenzhen female workers that Leslie Chang wrote about in the early 2000s.

During my doomscrolling, and some of them really saddened me. If you just search keywords like "Foxconn," "assembly line," "factory girls", "factory boys" (厂妹,厂弟)on Xiaohongshu, you can see tons of real documentation: what workers eat, where they sleep, their shift conditions, what they do after work. There are also many factory veterans"giving advice to vocational school students and high school graduates preparing to enter factories.

Behind this content is actually a complete factory culture and factory logic; a grim way of organizing people, controlling time, and stripping away identity.

This made me think—if US wantS to replicate a massive, complex, comprehensive manufacturing ecosystem like Shenzhen, then the social costs and structural prices behind it are far beyond what American politicians are actually thinking about when they're currently discussing "re-industrialization."

Another related example: director Yu Xinyan made a documentary called Made in Ethiopia, about Chinese companies setting up textile factories in Ethiopia. They established what's called the "Eastern Industrial Park"—just the name alone carries this heavy self-orientalist flavor, plus some Belt and Road style developmentalism logic.

The first part of the documentary tells the success story—thousands of Ethiopian female workers employed, smooth cooperation with the local government. But the focus of the documentary is on how to expand the factory to the second phase, they had to requisition villagers' farmland and promote village-scale migration. It was about trying to "system-switch" an agricultural society into one that accepts factory labor logic.

The film is full of conflict and tension: farmers' resistance, government buck-passing, cultural misalignment, and how Chinese-style production logic, such as progress determinism, gets forcibly transplanted into a completely different social soil. These scenes are extremely similar to the pain points in China's early manufacturing development.

Speaking of transnational factory landing, there's another example really worth paying attention to (which was previously mentioned): NPR's Planet Money recently did a follow-up episode about the Gotion story with more details, including how several consecutive town hall meetings in this small town gradually evolved into strong opposition to "Chinese capital entry." The whole thing essentially became a collision between American grassroots democratic politics and global industrial expansion.

Through these reports, I really saw the complexity of "industrial projects" in the American local context: how small-town political culture operates, how the public expresses opposition, how policymakers struggle to compromise.

Subscribe to Afra’s great substack and check out her podcast!

The Shinkansen, Japan's high-speed railway system, was built in the 1960s with a significant portion of its funding coming from a World Bank loan, not direct American funding. While the US was not a direct source of funding, the World Bank, which Japan borrowed from, is an international organization with significant US influence.

Bumingbai Podcast, 不明白播客 is a Chinese-language podcast hosted by NYT journalist Yuan Li, often discussing censored topics in China.

Dan Wang's essay "Definite optimism as human capital" clarified many ideas about industrialization and progress for me. I find myself coming back to it repeatedly.

This is the highlight. Period.

Afra: what a great undertaking — and a huge amount of work. Rich, insightful and timely. Thank you. Geremie

“but because they made me rethink the lived reality of ordinary workers under the factory system. The book spends extensive pages describing the real conditions of young female workers on assembly lines.” - yeah but you have to consider the alternative. If these girls didn’t work in a factory they’d be stuck with their economically exploitative family in the shitty countryside. Countryside does suck. Its boring as all hell, stifling, economically unproductive and life is uncomfortable and short. There’s a reason why every single peasant that could ran as fast away from the countryside as possible. You say these girls are living their worst life? I’d say they’re living a version of their best life.