When Arafat Met Zhou Enlai

History Sunday!

Zhao Gu Gammage is a recent graduate from Haverford College, where she majored in East Asian Languages and Cultures, and minored in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies.

Arafat Arrives in Beijing, March 1970

Thousands waited by the time Yasser Arafat stepped onto the tarmac of Beijing Capital Airport. Vice Premier Li Xiannian 李先念, along with other Chinese bureaucrats, orchestrated the whole affair: soldiers waited to enthusiastically wave Palestinian and Chinese flags, civilians waited to chant slogans expressing support for Palestine, and even foreign diplomats waited to shake hands and exchange greetings.

The Chinese people called the Palestinian people “heroic” (向英勇) and their struggle for liberation “just” (正义).1 They connected the Palestinian struggle with liberation movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, denouncing American imperialism and Zionism.

Arafat championed Palestinian nationalism through his decades-long leadership of multiple Palestinian groups, including the Palestinian Liberation Organization and Fatah, which he co-founded. He had recently returned from the USSR, where his 10-day stay was low-key, with no Soviet media coverage or meetings with upper-level officials. His trip ended with a devastating blow: Soviet aid was announced to support “Arab states,” an obvious snub that excluded guerrilla “liberation groups,” like Fatah.2

In China, however, he received front-page features in the People’s Daily (人民日报), a meeting with Zhou Enlai, and a promise that the People’s Republic of China would send cash and arms to the PLO.

The ongoing war between Israel and Hamas dominates news coverage and demonstrates America's sustained influence in the region. However, very little is known about China’s diplomacy in the Middle East, much less with Palestine. Even among scholars, China-Middle East research has just begun to emerge, with China-Palestine relations only recently becoming a hot topic because of the war. To find accounts of Arafat’s first China visit, l paired Mandarin-language digital archives of the People’s Daily with English-language academic publications.

China’s Developing Stance on Israel-Palestine

Immediately after the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, the PRC focused more on domestic stability and stability with their neighbors than with places like the Middle East. At the time, Arab countries were either struggling for independence or maintaining ties with the Nationalists in Taiwan.

China remained decidedly neutral on Israel-Palestine even after Israel’s recognition of the PRC in 1950 – the first in the region to do so. It would be another 40 years until China returned the favor.

On the eve of the Bandung Conference, the 1955 affair that assembled leaders from Africa and Asia, China finally developed its stance. China gave unequivocal support to Palestine in the hopes of gaining Arab allies. They noticed the importance that Palestine held to Gamal Abdel Nasser, then-president of Egypt and leader of Arab nationalism, and considered support for Palestine as key to winning over the Arab world.

The conference presented an opportunity for China to circumvent American containment — by 1955, American troops were in Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Forging international alliances was a useful tool for gaining recognition at the United Nations. Here, Zhou Enlai bonded with Nasser over their shared goal of Palestinian statehood, which led to the recognition of the PRC by the Arab world not long after. The PRC compared Palestine and China as two places with a common struggle against American imperialism. Like how the PRC claimed Taiwan as historically belonging to China, so too with Palestine and Israel. The PRC viewed Taiwan and Israel as agents of American imperialism. Portraying the Israeli state and Zionism as one facet of American imperialism paired with support for Palestinian freedom allowed China to build solidarity with Palestine and, on a larger scale, with the Arab world.

China and Anti-Imperialism

From the moment Arafat stepped onto the tarmac, he immediately understood that China viewed Palestine as the anti-imperialist struggle in the Middle East.

The anti-imperialist rhetoric from the “revolutionary masses” (革命群众数) had two sides.3 One expressed Chinese solidarity with countries to rule independently of colonial ties. The slogan “Firmly support the liberation struggle of the Asian, African, and Latin American people!” (坚决支持亚洲、非洲、拉丁美洲各国人民的解放斗争!) does exactly this.4 It placed Palestine within the larger global context of other liberatory struggles happening simultaneously. Thus, the slogan enables China to cast itself as supporting not just Palestine but the whole world.

Arafat played into this anti-imperial rhetoric as well. He considered China as the “fundamental pillar” (基本支柱) of the Palestinian revolution.5 He cited China’s military support for Fatah — and China’s status as the first country to offer such support — as a reminder of the struggle and friendship (战斗友谊) between them.6 Additionally, he coined the phrase “revolution grows out of the barrel of a gun” (胜利只有通过枪杆子才能赢得), a nod to Mao’s famous saying, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” (枪杆子里面出政权).7

Portraying Western imperialist countries as the enemy was something Arafat and the Palestinians easily agreed with. Arafat repeatedly heard the slogan, “Firmly support Palestinian and Arab people’s just struggle against American imperialism and Zionism” (“坚决支持巴勒斯坦人民和阿拉伯各国人民反对美帝国主义和犹太复国主义的正义斗争”).8 Through united opposition to Zionism and American imperialism, this slogan created a common enemy between the people of China with the people of Palestine.

Coincidentally, when Arafat was in China, the Chinese Red Cross’ donation finally arrived in Palestine. The donation of medical equipment, medicine, and clothes worth around 100,000 RMB was dispatched the previous year to the Palestinian Red Crescent Society. In return, the Palestinians thanked the Chinese, reiterating their shared struggle and writing, “Our two countries both suffered from the common force — the pain caused by American imperialism.” (我们两国都遭受到共同的武力——即美帝国主义所造成的痛苦).9

Throughout his visit, Arafat saw China’s ability to mobilize the masses towards “grasping revolution” (抓革命).10 Arafat saw the blue knee-high socks and matching uniforms dance across the stage of the Red Detachment of Women, the ballet epitomizing the Chinese Communist Revolution and revolutionary spirit under Mao. At the Huangtuguang’s People’s Commune, tucked in the Beijing suburbs, commune members repeated to Arafat the same anti-imperialist slogans that he had heard on the tarmac. Here, Arafat and his delegation observed the commune’s health center, factory, and school. At the PLA unit, Arafat again saw the PLA troops waving flags and chanting slogans, along with a coordinated weapons shooting.

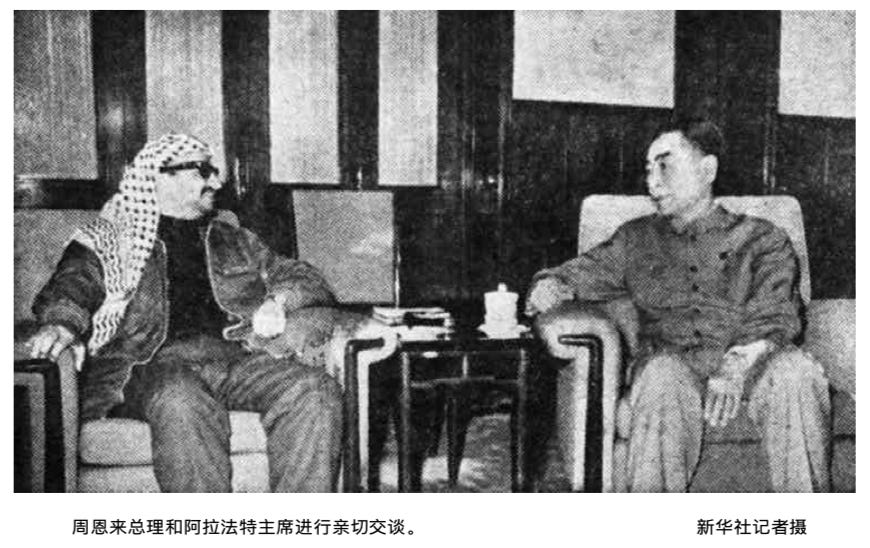

Arafat’s meeting with Zhou Enlai on his penultimate day in China was perhaps the culmination of his visit. Despite little news coverage of the conversation, the talk was “cordial” (亲切).11

Limits of Solidarity

Arafat’s week in China was marked by banquets and handshakes, but what did it actually accomplish? While the Chinese media created fanfare around his visit, he was in reality given a modest reception. Five years prior, in 1965, Ahmad Shukeiri, the then-chairman of the PLO, met with the top of the CCP, including Mao, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, whereas Arafat was handled by lower-level officials, such as Li Xiannian, meeting only briefly with Zhou Enlai. Arafat left China for North Vietnam, but returned to China many times before his death in 2004.

“巴勒斯坦民族解放运动(法塔赫)代表团到京李先念副总理设宴热烈欢迎贵宾,” People’s Daily, March 22, 1970.

Gwertzivian, Bernard. “Arafat at Ends Soviet Visit Without Sign of Success,” The New York Times, February 21, 1970.

“巴勒斯坦民族解放运动(法塔赫)代表团到京李先念副总理设宴热烈欢迎贵宾,” People’s Daily, March 22, 1970.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“支援救助受伤的突击队员和巴勒斯坦难民工作,” People’s Daily, March 24, 1970.

“巴勒斯坦民族解放运动(法塔赫)代表团参观北京黄土岗人民公社受到热烈欢迎,” People’s Daily, March 27, 1970.

Ibid.

Great historical recount, especially the consistent China policy against American Imperialism, which still exists today. We Americans are soooo naive!