Serious or Not

Anduril's Christian Brose on American Defense

Chris Brose is the President and Chief Strategy Officer at Anduril Industries. He’s been at the forefront of the debate about how America needs to change in order to win a future war against a high-tech adversary like China. He’s the former staff director for the Senate Armed Services Committee and the author of The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare.

We discuss:

Why the U.S remains dangerously vulnerable to low-cost drone attacks and what it would take to get serious about defending the homeland,

How bureaucratic logjams and budget dysfunction stall America’s adoption of counter-drone and other critical defenses,

What the Ukraine war reveals about the future of warfare and what the US has yet to learn from it,

Why confidence in American technological superiority is misplaced, and why state-of-the-art weapons may not guarantee a quick or decisive war,

How humans will make military decisions in the age of AI.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app.

Getting Serious About Defense

Chris Brose: We were out in Ohio for the Ohio State-Texas game, which was awesome. We’re sponsoring OSU because of we’re building a major factory in Columbus.

Jordan Schneider: You guys are building a factory in Ohio? Why are we not building factories in places that can’t be blown up easily?

Chris Brose: Ohio is definitely on the list of places that cannot be blown up easily. It’s inland in a good location. This doesn’t necessarily need to be a deeply buried target. If we’ve got foreign adversaries bombing the American mainland and our production facilities, we’ve crossed into really bad territory a long time ago.

Jordan Schneider: Fair enough. Speaking of being afraid of catastrophic homeland attacks, what Israel did to Iran, what Ukraine was able to do to Russian bombers — that hasn’t completely sunk in here. How freaked out should folks be about that sort of drone attack?

Chris Brose: I don’t want people to lose sleep over it daily, but they should be freaked out about it. We’re living on borrowed time in this regard. We’re looking at the proliferation of low-cost drones, the ability to make homemade drones with explosives integrated (very similar to what the Ukrainians or the Israelis have done), and orchestrate a similar type of attack in the United States against a critical military target or other types of targets. That is eminently in the realm of the possible.

This is a 9/11-style problem that we’re still adopting a September 10th mindset to. To some degree, those types of attacks have been a wake-up call for those who weren’t already awake to this problem. The US Government is putting more energy into thinking through what we need to do to get ourselves secure on the homeland against these kinds of proliferated potential drone attacks.

Jordan Schneider: What does actually being serious look like?

Chris Brose: Being serious means first recognizing the vulnerability we have, rather than hand-waving it away. Then it’s moving with urgency to solve the problem. Funding’s also necessary to buy capability and get it fielded to the critical sites that you need to defend. An enormous amount of policy and bureaucracy is going to have to be settled and broken through in order to do this.

When you look at counter-drone in the United States, there are multiple different government agencies that own different parts of the airspace. They have policy control over different functions in terms of what you can do to defend against assets from aerial attack. Typically, this has resulted in paralysis. Government agencies and congressional committees fight with one another and yell at one another, but they don’t solve the problem.

The real challenge is going to be, can we bust through all of that policy and bureaucratic logjam and actually start getting solutions fielded in an integrated way that protects the places that need to be most protected?

Jordan Schneider: Andrew Marshall had a quote on the development of new sources of military advantage:

“The most important thing is to be the first, the best in the intellectual task of finding the most appropriate innovations in the concepts of operation and making organizational changes to fully exploit the technologies already available and those that will be available in the course of the next decade or so.”

We also have this quote from Anduril founder Brian Schimpf talking to Ben Thompson on Stratechery:

“The fundamental thing that has to be true is that we have independent conviction on what the right answers are. As we’ve scaled, when we have a business unit that doesn’t have that, the results are trash. It’s obvious that they don’t have the vision.”

What is the right division of labor between the government and the private sector for imagining the futures that Andrew Marshall is alluding to?

Chris Brose: I agree with the Marshall quote, but I could also argue the inverse. He’s saying organizational and operational change enables government or the military to harness technological innovation and change. That’s true. But the reverse is also true — unless and until you have real technological change and adoption of new technology, it’s very difficult for the government to understand and envision new ways of operating and organizing.

The division of labor in that regard is that the government will understand its problems. To the greatest extent possible, they need to rely upon private companies, innovators, people who are thinking creatively about different types of solutions, who understand the available technologies that many in the government don’t fully understand or appreciate, and how they can be combined together into solutions that well-meaning people writing military requirements might not necessarily come up with on their own.

The role of the government then is taking those new capabilities and doing what they uniquely need to do — figuring out new ways of operating and organizing themselves to take maximum advantage of what these new capabilities offer and genuinely present new types of dilemmas to the adversary. Industry can’t do that for them. The best that industry can do is set them up and enable them with new capabilities, additional capacity, and basically other predicates that open up the opportunity for them to really rethink how they operate and organize.

Jordan Schneider: But this is a new dynamic. Anduril, the defense tech sector at large is saying that 30 or 40 years ago, this would all be happening in-house, more or less in the government.

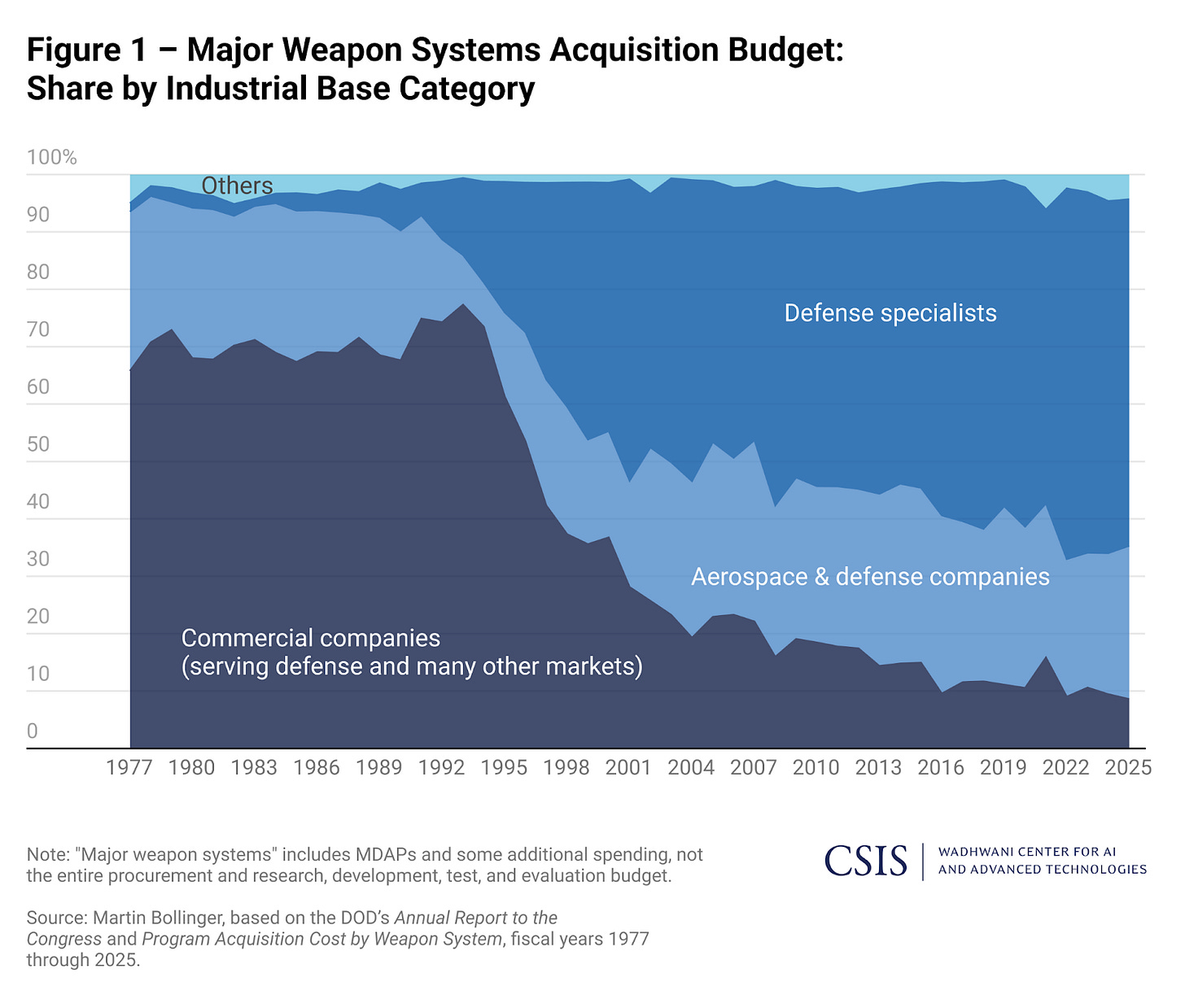

Chris Brose: Yes and no. You could even argue that less of this was happening in-house 30 or 40 years ago. We’ve gone through this period in the US where we had an incredibly vibrant industrial base, a defense industrial base, back during World War II, early-mid Cold War, late Cold War. What we’ve seen over the past generation is this hyper-consolidation — post-Last Supper things that people have talked about — that has really created something that has never existed in the United States from an industrial base standpoint: a hyper-concentration of defense manufacturing and development in basically five or six companies.

That is very opposed to the way our industrial bases traditionally functioned, where the government had a lot more diversity, a lot more partners, a lot more competition, a lot more pressure for innovation that was happening in the private sector because there was very much a perform-or-die type approach. Since the 1990s it’s been a bunch of companies that are too big to fail. The results of that are things that are now becoming very apparent to people.

Jordan Schneider: Staying on this, I’m curious about your sense of where the new doctrine comes from. You wrote about this in your book about how, at the end of the day, when you’re talking about great powers, people have roughly equal toys. It’s how you use them that ends up providing you the edge in a new military revolution or a new age of combat.

And it seems like what Anduril and this new defense ecosystem is envisioning is playing more of an active role in imagining what that doctrinal future is than defense contractors were 20 or 40 years ago.

Chris Brose: Because we’re at the cutting edge of technology, we absolutely understand the capabilities that we’re building and providing, and the opportunities that open up to operate differently and to structure and organize the military differently. We’re going to be less opinionated on those operational and organizational questions just because that is clearly the domain of the government.

To answer your question directly, the new ideas and the really game-changing ideas for operational and organizational change will come from the government and the military. In my experience, they will typically come from lower levels, not necessarily higher levels. It’s more of an organic bottom-up type of innovation as opposed to someone on high whose first name is “Secretary” or “Chief” mandating that the organization change.

But what I wrote about in my book and still believe to this day is that you have to have both together. Oftentimes, when you have bureaucratic disruptors — people in government who are seeking to change at a lower level — if they don’t have the top cover from political leadership or military leadership, they tend to get squashed. At the same time, you’ve seen many examples of well-meaning political leaders or military leaders who want to change their institution. They have a vision of where it needs to go, but they can’t bring the organization in line to follow them and to get it adopted in a way that when they roll out of their job in two or three years, it stays.

On the government side, there needs to be an empowering of lower-level disruptors, operational leaders and commanders who are going to oftentimes push those novel ideas up. But you need change agents at the top who are looking for those people and those ideas and really trying to drive it through.

Jordan Schneider: You had this very striking line in the conclusion of Kill Chain — “It is hard to escape the conclusion that America is still not serious.” How has the balance of serious versus non-serious shifted across different universes of organizations?

Chris Brose: Let’s first determine what we mean by “serious.” Seriousness is judged not by what people say, but by what they do in terms of actions they’re taking, money they’re moving, programs they’re starting — whatever the metric is.

When I wrote my book, as I looked back in recent decades, I was shocked by how many people have been saying more or less similar things to what I wrote in my book. Andrew Marshall is obviously a top example. These aren’t brand new ideas. What’s shocking is how often we have failed to do the very things that we said were necessary and important.

For me, the definition of “serious” is — are we actually doing the things that we say we need to do? Are we changing our institutions at scale, not just science projects and innovation theater? It’s impossible to argue that we haven’t made progress in the last five years, but are we as a country serious yet? No, I still don’t believe that we are. We’re getting there, and there are people who are doing their level best with the powers that they have to be serious and change their organizations.

But I look at, for example, the budget process, where the Department of Defense is on a full-year continuing resolution, which means they’re locked into the budget from a year ago and lose flexibility in what they’re able to do because we can’t agree as a country how much money we should be spending on defense. At the beginning of the fiscal year, the Department of Defense actually needs an appropriated budget so they can move out with the process of changing themselves.

It’s hard to argue that we as a country are serious when that kind of behavior is still happening and, frankly, becoming more mainstream. If we were serious and we started to get our act together, that wouldn’t happen. I’m not an expert on the Chinese Communist Party’s budget process, but I’m pretty sure that the Chinese military is getting its money at the start of their fiscal year.

Jordan Schneider: Well, they do have other problems, but let’s get to an executive branch example.

Chris Brose: The counter-drone example is a really good one. We have massive vulnerabilities in this country. Operation Spiderweb could absolutely 100% happen here today. I don’t think it would actually be that difficult to orchestrate.

If we’re continuing to remain vulnerable to that kind of an attack — a 9/11-style surprise, violation of sovereignty, loss of life, loss of critical military assets — if we’re still squabbling over the terms of policy and bureaucracy, if we’re not spending the money to a degree that we need to spend to solve this problem, if we’re not leaning on new companies that are bringing new technologies and capabilities to bear, not just in demonstrations but fielded and performant in operations, again, it’s hard to argue that we’re serious.

But there are people now that I can point to who are absolutely moving out with seriousness. Just as one example, the Secretary of the Army and the Chief of Staff of the Army should be commended for how much they are trying to do to change their organization. The Army is the largest military service with the most people, the most money, and the most things. It is a very difficult supertanker to turn around. In a matter of months, you have two leaders, civilian and military, who are trying to cut away from old legacy capabilities that they don’t need anymore, and are trying to reorganize themselves from a procurement and acquisition, and technology adoption standpoint. They’re rethinking how the Army needs to operate.

Nothing is off the table there. Obviously, the proof will be in the pudding and all of the actions that need to follow. But there’s an enormous amount that’s been done already. That’s an example of how much committed senior leaders can really change their organizations and adopt change for the better.

Lessons from Ukraine

Jordan Schneider: Williamson Murray and MacGregor Knox wrote, “Revolutions in military affairs take place almost exclusively at the operational level of war. They rarely affect the strategic level, except insofar as operational success can determine the largest strategic equation — often a tenuous linkage. So revolutions in military affairs remain rooted in and limited by strategic dividends and by the nature of war. They are not a substitute for strategy, as so often assumed by the utopians, but merely an operational or tactical means.”

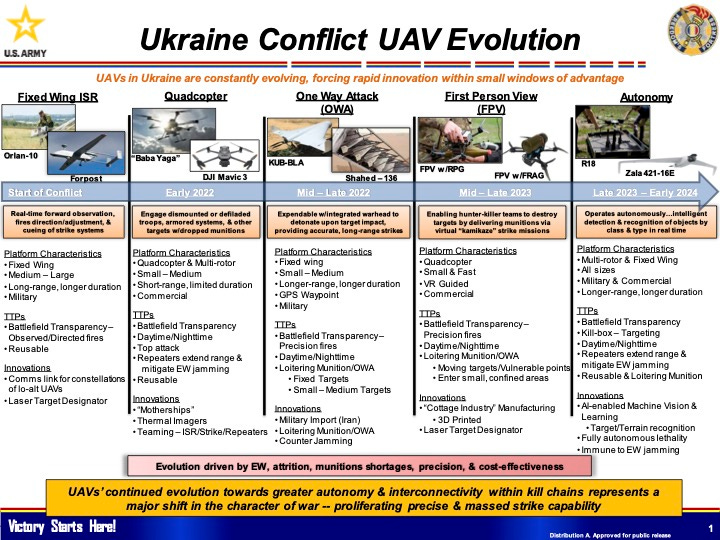

When people look at Ukraine and at the future of war in general, there is a bias to sell your thing, get attention, raise money, to envision something utopian or promise something that is like a complete game changer. But one of the big takeaways for me from Ukraine is that folks should have relearned the lesson that operational silver bullets don’t exist. You have this wild dance where things are changing all the time, and whatever you started with is not what you’re going to end up with two years later, much less six weeks later.

Chris Brose: There are examples of military technological revolutions that have a strategic impact. Nuclear weapons come to mind. A lot of what we’re seeing in the cyber domain is certainly something that has strategic implications. When you start looking at the reality of nation-state adversaries deeply disrupting and destroying in many respects the fabric of the way of life of another country, because they can target critical infrastructure, they can target the lifeblood of what we in this country frankly take for granted on a day-to-day basis. That has a pretty significant strategic impact.

AI and autonomy speed up and increase the scale of warfare, where it begins to take on a strategic implication. But your point about Ukraine is right. America has had to learn this.

For the past generation, we’ve assumed that we’re far ahead in terms of military technology, that we can afford to have a very small number of very exquisite things that are going to do the work for us. If, God forbid, we find ourselves in a conflict, it’s not going to last very long. We’re not going to shoot many of those weapons. We’re not going to lose a lot of things. We’re not going to have to replace a lot of things. That’s been a bit of our lived experience.

Ukraine is much more of a back-to-the-future type moment, where you realize that actually, every war that we’ve fought has lasted a long time. Where we’ve ended up is not even remotely close to what we started with. That pace of innovation and change and adaptation and learning is the whole game. How quickly can you understand the changing character of the battlefield, what your adversary is doing, what technology enables you to do, roll that into learning and development and fielding of new capability, operational and organizational change that comes from that? Recognizing that all of the gains that you might be able to eke out are themselves going to be fleeting. Whether that’s a matter of weeks or months or maybe a year, you’re going to have to keep that cycle incredibly tight and incredibly fast.

We’ve frankly missed an enormous opportunity as a country to really think about Ukraine as a catalyst for changing the way we operate. The Department of Defense, and the US Government in general, deals with things that it plans for, and it deals with things that it doesn’t plan for. For the latter, in my experience, it generally wants to say, “I didn’t see this coming. I don’t want to have to deal with this. I’d rather just get back to the regularly scheduled program.”

That’s how we’ve addressed Ukraine. We have provided a lot of support over a few years, but we’ve largely just grabbed things that were off the shelf — legacy programs of record, stockpiles of weapons, many of which have been very useful to them, but many of which have not been useful in the least.

We’ve really missed an opportunity to recognize that in supporting Ukraine, we have an opportunity to adopt that pace of change ourselves, to realize that this is the absolute frontier of warfare right now. If we can’t solve these problems for ourselves, let alone what they’re going to look like, God forbid, in a China scenario, which is all 10x worse, we are going to find ourselves on the back foot if we end up in a conflict like that.

There’s a lot more we could have done in terms of really looking at this as a proving ground for new technologies and new capabilities that could not just help the Ukrainians win, but help the US military change itself at scale with a lot more speed. Perhaps there’s still an opportunity to do that.

If, God forbid, we ever find ourselves in a conflict with China, all of the assumptions of Ukraine apply. It’s not going to be short. In all likelihood, we are going to lose a lot of things, we are going to have to replace a lot of things, and we are going to have to change and adapt at a speed that we’re really not used to as a country.

The Problem of Scale

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about scale for a second — another big lesson of Ukraine. We had a guest on the show a few weeks ago who left the CIA. I asked him, “What’s your favorite document?” He goes, “Well, this thing’s public. Each Chinese province has a war scaling exercise where they get all the companies in the room and work out, ‘Okay, how are we going to build 100x of this, 100x of that?’” America did that until 1947 and basically stopped. It was very striking to me. Another Brian Schimpf quote about how this was something that you guys are explicitly planning when you think about building things is finding partners that could go 10x or 100x. Reflections on that? Is this something that other people have going through their heads?

Chris Brose: I can’t speak for other people. The way we think about it is that the amount of capability that the United States is going to have to have for a peer fight is probably an order of magnitude larger than what we have become used to or accustomed to over the past 30 years. This isn’t a new insight. If you go back to World War II, for example, we won that by outproducing our adversaries. We were producing at a scale that was just eye-watering.

In the past 30 years, we’ve become enamored of the idea that we could basically build a military that is irreplaceable. It’s small, exquisite, and echnologically bleeding edge. And because we were far ahead of our competitors, if we ever had to fight, it was not going to last long. We weren’t going to lose much, we weren’t going to have to produce much or replace much. That’s just ahistorical in terms of what the experience of the United States at war has been since we were a country.

If the problem becomes, “All right, how do I 10x or 20x production of vehicles and weapons and not just do it once, but sustain it as a function of time — perhaps in mountains, perhaps in fields, perhaps on islands or at sea or in outer space — because I don’t want to limit options in the future,” then everything’s on the table. But the real question becomes, how do you actually design capabilities to be mass-produced?

If you look back at World War II, that’s what we were doing. You could take over the Willow Run automotive facility and go from making commercial cars and trucks to making B-24 bombers. Those bombers weren’t wildly different than the commercial vehicles that were being built on those lines prior. It’s impossible for me to believe that a Ford factory today in Michigan could build B-21 long-range strike bombers. Every aspect of it has just become completely different and divorced from commercial supply chains, manufacturing, etc.

But when we look at this problem, it is absolutely doable. When Tesla entered the automotive industry, they were laughed out of the room by Wall Street and by traditional automotive manufacturers because the production targets that they were putting on the board and the speed with which they were claiming to be able to do it had never been done before. Today if you look at one of those Tesla Gigafactories, they’re producing four to five thousand vehicles a week. Yet when you look at the production that passes for large scale in the defense industrial base, it’s a few hundred weapons a year, maybe a few thousand weapons a year, but it’s nowhere close to what commercial manufacturing is able to achieve.

The first premise needs to be, you need to leverage as much of the commercial industry as you possibly can. You need to design weapons and military capabilities to be mass-producible. If you don’t do that, there’s no way at all downstream that you’re going to solve that problem with more money or more feeling or anything else you might want to apply to it.

At the level of design, you have to simplify it. You have to make conscious decisions to lean on commercial manufacturers who have tons of capacity and, in the event of a war, could easily be flipped over from being 5% defense, 95% commercial to the other way around at the direction of the government. But if you’re not making those choices at the beginning, you’re never going to be able to produce at the scale that you want, and you’re never going to be able to sustain that over time.

Whether it’s autonomous fighter jets that we’re building for the Air Force or robotic undersea vehicles or weapons of all kinds, that design principle is at the core of everything that we’re doing. That’s why we’re going to be able to make good on the commitment we’ve made that we’ll be able to do 10x production of what typically passes for large-scale production in the defense industrial base.

Jordan Schneider: A provocation from Dan Wang’s new book Breakneck:

“AI can’t distract us from broader American deficiencies. As relations between the US and China become more hostile, the chances of a conflict grow. The US is facing a peer competitor that has four times its population, an economy with considerable dynamic potential, and a manufacturing sector that can substantially out-produce itself and its allies. If China and the US ever come to blows, they would be entering a conflagration with different strengths.” Would you rather have software or hardware?

Chris Brose: It’s a false choice. I say this as a company that is trying to be leading edge in both. At the end of the day you’re going to need hardware. There’s just no two ways around it. As long as human beings exist in the real world and occupy physical space, hardware is going to continue to be relevant.

At the same time, what’s really changing is that previously we’d always faced this choice between you could have mass, but it was going to be dumb, or you could have precision, but you weren’t going to have quantities of it. The real opportunity now is that you can put those two things together, and you can do it at an affordable price. You can have low-cost weapons, low-cost drones that are also enabled by highly intelligent, highly capable software. You get both mass and precision at an affordable price.

Putting aside the US and China, what this does is it opens up the level of geopolitical competition to countries that previously would not have had access to that level of throw weight in the international environment because they had been limited by size of territory, size of population, size of economy. What’s happening now technologically, both in terms of software, AI and autonomy, as well as in low-cost manufacturing and other kinds of product production changes that are occurring, is the ability for a small country to actually punch enormously above its weight from the standpoint of military capability.

Jordan Schneider: We have the floor being raised — precise mass or mass precision, we haven’t decided yet. Lots more people can do crazy drone attacks on a waste treatment plant halfway across the world. But there’s also this other aspect of what Dan was getting at: you’re trying to make production and supply chains that can go 10 or 20x, but it is hard to compete from that perspective with the world’s factory, right? What’s going to have to give there?

Chris Brose: Unless we’re prepared to just say at the outset, “We’ve really screwed this up for the past 40 years and we might as well surrender,” the question becomes: okay, you have to accept the reality of where you are, which people are starting to do. But it still seems the case that people haven’t wrestled fully yet with the implications of what 40 years of essentially US outsourcing and deindustrialization at a time of Chinese hyper-industrialization has really brought us to.

The shipbuilding example is a good one that’s often used — 220 times the capacity of shipbuilding in China relative to the United States. If we get into a conflict and we start losing ships, this is going to be a really hard problem for us to solve.

The answer isn’t to go back in time and try to recreate a bunch of old industrial muscle that we’ve lost. The answer is what we’re trying to do, what a lot of other new companies are trying to do, which is try to create new and different muscles that can actually be put in place much faster.

As I look at where we are as a company, we have millions of square feet of production capacity that are coming online all over the United States, in allied countries. It’s happened in a matter of a couple of years really. The ability to scale that as we become a larger company, as other companies become larger — it’s just that those factories are going to have to be building different things. They’re not going to be building aircraft carriers and destroyers and long-range strike bombers. They’re going to be building autonomous fighter jets and robotic submarines and low-cost cruise missiles and drones and other things that can be built quickly, where you have a workforce that is skilled enough to be able to mass-produce those kinds of things in the United States.

We are absolutely in a bad way from a hardware and manufacturing capacity standpoint. We have given up an enormous advantage in this country, and China has absolutely seized that. We are where we are. That being said, I don’t for a moment believe that all hope is lost. Going back to your point, if we are serious, there is an ability to create new production capacity in this country to mass-produce the kinds of military systems that we’re going to need to generate and sustain deterrence. If we end up in a conflict, God forbid, to be able to fight it, sustain it, and win it over time.

Jordan Schneider: Coming up to the strategic level, another way to answer China’s ability to manufacture is, as you alluded to, getting the rest of the world on board as well. You wrote pretty compellingly that on the one hand it would be nicer for allies to do more and spend more money, but let’s not forget that they are actually allies. It’s been a weird few months. We’ve seen Europe say they want to spend more, but also say they want to have their own homegrown stuff. Take this wherever you want to.

Chris Brose: There’s been enormous change in recent months — tariffs, political shifts, and upheaval of existing practices. But the sky isn’t falling.

We’ve made a clear break with the past, signaling to business, government, and allies that we’re moving away from the old order. Much of that arrangement wasn’t great anyway. The question is: what comes next?

Look at European commitments to increase defense spending, which are considerable. For years, we dutifully read talking points to NATO allies that they needed to spend more. Some did, most didn’t. Now they’re actually doing it seriously, and the administration deserves credit.

Unsurprisingly, with all this uncertainty, European governments want that investment creating sovereign, homegrown capability — employing their people and ensuring they’re not dependent on others. With the US speaking similar words, it’s not surprising to hear this from Europe too.

This still creates opportunity for US companies. If we can’t just produce in American factories and ship to Europe — because it’s politically problematic for our allies — there are other ways. We’re collaborating with major European defense companies like Rheinmetall and setting up indigenous operations in allied countries, genuinely becoming part of their industrial base. Look at Rolls-Royce or BAE. They’re British companies, but as much part of America’s industrial base as Boeing or Lockheed Martin.

The US has a great advantage in our dense network of allies bound by common interests and values. The question that’s always bedeviled us is how to operationalize that at scale, how to multiply the power of all these countries to generate offsetting mass to China, for example.

That’s imminently possible right now with all this churn and acceptance that we’re not going back to the past. We’re building something new. I’m eagerly awaiting government action to chart how we collaborate with main allies in Asia and Europe. It’ll look different than historically. That’s okay. There’s enormous opportunity for those thinking creatively and moving aggressively when people are serious about solving problems.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of sovereign capability and things looking different than they did before, how do you feel about nationalizing primes and putting the Defense Department on the Anduril cap table?

Chris Brose: I understand why the government is considering equity stakes in defense contractors. For years, a handful of hyper-consolidated companies have relied entirely on government contracts while delivering late, over-budget programs. The government owns all the downside without real control over performance. The market has become such that you can’t even call it a market. It’s hyper-consolidated with too-big-to-fail players that the government doesn’t really have options.

For the government to come in and say, “If you want me to build you another facility to produce more, right now I want a piece. I want to be at your board, at your table, with a real voice for how you’re running the company, how you’re using profits, how you’re structured” — I totally get why this is a conversation we’re having now.

But this would be catastrophically bad right now. Unlike Intel, which serves commercial markets, defense contractors operate in a monopsonistic environment where the government is the only customer. For the government to award contracts to companies it partially owns creates massive conflicts of interest. It’s the same reason defense secretaries must divest holdings in defense companies.

In an environment where you effectively had hyper-consolidated large defense companies you could count on one hand, it would make sense for the government to say, “In order to compel performance, in order to keep programs on cost, on schedule, I want to have more agency over how these companies are functioning.” I get that.

But the timing makes this doubly ironic. After a generation of walking away, we finally have an explosion of new defense tech companies. Dozens are being funded by billions in private capital, building innovative capabilities, competing against the legacy players. Taking ownership stakes in the largest incumbents just as this competitive renaissance emerges would undermine the very dynamism we need.

In a market with only a handful of players, government ownership might make sense to compel performance. But when energy, money, and talent are rushing back into defense to create real competition, this is deeply problematic.

Autonomy and Arms Control

Jordan Schneider: The future of command and control — what won’t humans be doing? What will humans still be doing, maybe five, ten, twenty years down the road?

Chris Brose: First, we need to separate command and control. They get bundled together and are often referred to as C2, but command and control are very different things. In a human setting, commanders who are providing their intent — their overall objectives and guidance — to subordinate agents, whether those are people or, in the future, could be robotic systems. Those commanders are not telling them every single thing to do.

They may trust certain subordinates more and give them a wider berth or more flexibility in what they’re able to do. But those commanders are providing the left and right limits under which the forces that report to them are making decisions and operating. Control is executed more at that subordinate level. There are instances where a commander will reach down and directly control an outcome because it’s important for that individual or for the mission. But the way the US military functions is very much around delegation of authority to the lowest level. It’s what makes us different than the Chinese military or the Russian military, and it’s a massive superpower.

This delegation of authority is the whole basis of command and control. This is why I don’t think it’s crazy at all to take that exact framework and apply it to how human beings in the future will be interacting with robotic systems or autonomous systems. You still have a human commander in charge who is fundamentally making a couple of big decisions.

One is determining whether some object on the battlefield is a legitimate military target. That is something I think we want a human being to decide. The decision may be enabled by a lot of technology like sensors and machine learning but at the end of the day, a human being needs to say yes, that is a legitimate military target that I want to do something about.

The follow-on action of doing something about it — the controlling or initiating an act of violence — is something that we’re going to want a human being to at least say, “This is a decision that I want to take.” My own view is that, beyond that, most of this can actually be automated. It can be a set of practices or robotic systems where human beings can still execute commands but be more reliant upon autonomous systems or processes to engage in the control of the decisions they’re setting themselves.

Jordan Schneider: Waymo, right? Everyone has this vision. The pitch they’re making is, “Look, this is better than 99.9% of drivers, or it’ll get there soon. You should trust us instead of driving.” There is a long and storied history of targeting decisions gone awry. Why do you think there should be human beings deciding which, I don’t know, Venezuelan boats to blow up?

Chris Brose: A human being will make the final decision. It’s a classification decision enabled by technology, but determining civilian versus legitimate military target — I’m not sure we’re ready to hand that off to robots.

But I would tell you that most of these decisions, all of these decisions, are highly contextual and circumstantial. I find the debate often becomes this very monolithic debate of, in the abstract, what are we willing to delegate to robots.

This conversation looks very different for offense versus defense. In defensive operations — protecting against inbound enemy drones, weapons, missiles threatening a ship, base, or city. You’re going to delegate a lot more because the speed at which you have to make that decision is much faster. The requirements are much faster, and the consequences of being wrong are much higher in terms of actual loss of life to your own forces or population.

For offense, for force projection — going out to find and destroy enemy targets — we’ll be more cautious about what we delegate to autonomous systems without human-in-the-loop supervision.

Another example — the way the US military operates is not that we’re going to go fight wars that are endless in time and space. We are going instead to identify very specific geographic locations that we are going to define as areas of active hostility. This is US military doctrine. It’s the law. Inside these carefully drawn zones, commanders relax thresholds for using force due to mission and force protection risks. This doctrinal framework can absolutely be adopted for autonomous systems. It’s not loose killer robots everywhere for all time. It’s communicating to the world: “Don’t go here because I’m treating this as a battlefield,” while giving our forces more leeway to use force they might not employ elsewhere because the mission must succeed and you must protect the humans operating there, military and civilian.

Jordan Schneider: It seems there’s a lot of competitive pressure in delegating more. Maybe the tech isn’t ready, and this is a 2040 or 2050 thing. But when you have autonomous systems that can escalate situations with strategic consequences you didn’t intend, that’s probably where you still want human oversight.

Chris Brose: That pressure is there. If militaries see an operational advantage to be gained by delegating more to autonomous systems, by removing human control that slows processes down, if it enables them to operate at larger scales because you can now have a human-to-machine relationship or ratio that enables one human being to deploy or supervise lots of robots or weapons — countries are going to do that.

I would say China especially is going to do that because, to the extent that I understand it, their entire military structure is based on the belief that senior leaders do not trust their subordinates. They do not want empowered lower levels with guns running around with their own ideas and opinions.

It’s not a huge logical leap for me to believe that the Chinese military, as a matter of doctrine, is going to be far more willing to delegate these kinds of decisions to robots that they believe they can control, as opposed to human beings who may have a mind of their own — a group of folks who are armed who decide that they might not want to follow orders, or they might not like the regime, or they might want to take matters into their own hands.

Jordan Schneider: I’m not sure how you spent your Tuesday night, but let’s do China parade takes. I’ve got one from the peanut gallery — their CCAs seem much bigger, and some are tailless compared to the Fury.

Chris Brose: I’ve been too busy this week to read deeply into all the moment-by-moment takes of what’s been coming through. The Chinese Communist Party puts on a hell of a parade, hats off. It was super impressive. The marching is very high level. I did not have a chance to see every piece of the military system rolling through.

I’ll offer an opinion related to a question I have. The benefit of these things is that you get to showcase your hardware. Arms control and verification are built around this idea of “I can see things in the real world, I can observe them, I can count them.” This is how we did arms control with the Soviet Union. How many warheads do you have? We’re doing open skies observations of deployed nuclear forces, et cetera.

But how do you verify the level of autonomy of a robotic system? How do you verify what the software of that system enables the drone or robotic submarine to be able to do? That is a massive operational advantage for a country. Their collaborative combat aircraft are probably not going to look wildly different than ours. Their fighter jets certainly don’t because they have a very long and effective history of stealing those industrial designs from the United States.

If you see two drones that look more or less alike, one of them may have a level of software that is 10x better that enables it to do wildly more effective things in operations than the other one that looks identical to it. How do you verify that? How do you understand what its capabilities and limitations are? How do you begin to even think about an arms control regime for these types of capabilities?

We’re all better off not getting into an arms race dynamic. But the reality that people have to contend with is that this is an incredibly difficult set of technologies to observe, to verify, to understand what it’s capable of doing and what the military advantages that each respective country is gaining from those technologies are.

I’m realistic/cynical about the prospects for getting into some type of arms control regime on AI-enabled systems or autonomous systems for those reasons.

Jordan Schneider: That’s the lesson of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s as well. You had arms control, but it was on stuff that didn’t matter because both countries could still totally blow each other up. And by the way, you had SALT, and then SALT ended three years later and they tried to do it again. Everyone was still trying to make new and better tanks and bombers and fighters at the same time. I share your pessimism on this one.

Chris Brose: People spend a lot of time thinking about arms control for AI. I’m all for having that conversation. I want the advocates of it to start from a realist understanding of the world in which we’re living, to understand the consequences of getting into a one-sided arms control negotiation, of limiting ourselves. The reason arms control worked between the United States and the Soviet Union, such as it did, was because both sides had nuclear arms.

Jordan Schneider: They weren’t giving them up.

Chris Brose: They were limiting them, fundamentally. Your point is right. They still had nuclear arsenals that could destroy the planet multiple times over. They didn’t necessarily need to build two and three times more, but they would have had that dynamic constraint not been put in place. But the point was that constraint, to the extent it was effective, was effective because you were counting things you could count. You were measuring and observing things you could measure and observe.

I don’t know how you do that on software. We’re going to be reluctant to hand all of our source code over to the United States government if they didn’t pay for it. Why in the world are we going to do that to the Chinese so they can verify the level of autonomy that our collaborative combat aircraft has, so they know what its capabilities and limitations are? It’s just never going to happen.

It’s fine to have that conversation, but let’s actually have a debate from a position of facts and reality rather than hopes and dreams.

Jordan Schneider: On the other side of this, you have stuff like chemical weapons or blinding lasers and stuff like that. It just seems to me to be a very different category than this all-purpose technology which is going to go into everything.

Chris Brose: Also true. The other little inconvenient fact about chemical weapons is the reason nations engaged in arms limitations for chemical weapons after World War I is that they realized they didn’t work very well. They were played out. By 1917, it was shoot mustard gas at the trench over across from you, and the wind changes and it blows it all back into the faces of your own soldiers.

There was an incentive for these countries to limit weapons that they themselves had developed, had used, and found to be not as effective as they had thought. There’s a realism governing why they engaged in these kinds of arms control in the first place. But to be very clear, they built them, they used them, and only then did they engage in a limitation.

Jordan Schneider: Now it’s like cluster bombs are back, landmines are back. You don’t use the thing until...

Chris Brose: You don’t use those things until you realize that you need them. Ask the Ukrainians about landmines and cluster munitions or area destruction capabilities. They absolutely have a need for them. What is the easiest way to clear a minefield? It’s not driving robotic bulldozers through it. It’s hitting it with a cluster bomb.

For a long time we had this luxury. We took this vacation from world history and we thought that we had somehow gotten beyond all of the lessons that we had learned in previous wars. We thought that we could do without this or we would never need to produce at the scale that we did in the past. And here we are, back to the future.

Orban’s Cannons

Jordan Schneider: Speaking about lessons from world history, you mentioned you were reading 1453, an account of the Ottoman siege of Constantinople by Roger Crowley, which is very well written. What struck me was the story of Orban, who’s this mercenary gun master. He was from Hungary or Wallachia.

He first goes to the Byzantines but they’re too poor. So he goes across the river and hangs out with Mehmed II, who signs a big contract. He makes the biggest gun the world has ever seen. His cannon could shoot 700-pound rocks. It was able to knock down this wall that had been improved upon over the course of 2,000 years. But Mehmed the Conqueror says, “Keep shooting it, keep shooting it.” Orban’s like, “I see these cracks, maybe we shouldn’t.” And it eventually blows up and kills him. What lessons does this story have for the future of defense acquisition?

Chris Brose: Pay attention to the limitations of your technology. To take a step back: Why am I reading this book? I’ve been on this weird Middle Ages kick for the past couple of years because I find that we do, as a country, an incredibly terrible job teaching history to kids. I have a 12-year-old and a 15-year-old and it is just shocking how bad their historical education is.

I find myself needing to be a history teacher to my children. It’s frustrating because history is literally the written record of the most interesting stuff that’s ever happened. How can teachers make this boring?

My dad was a historian. I’m not a history major, I’m not a trained historian. I’m just interested.

Jordan Schneider: What was his period?

Chris Brose: It’s actually very germane to this conversation — he studied and wrote on changes in technology, specifically 19th and 20th century Europe with a focus on Germany. He actually wrote a very cool book called The Kaiser’s Army, which is about how the German military learned all of the wrong lessons from the Franco-Prussian and Austro-Prussian Wars. That really didn’t set them up well for the opening days, weeks, and months of World War I. You can find it on Amazon. It’s not a bestseller, but it’s a great read.

As for the Middle Ages, people see it as a “dark age.” You had the Greeks and Romans, and then things picked back up with the Enlightenment and the Renaissance. In this thousand-year period, some stuff happened. Wars, plagues, barbarians, the Crusades, and then the Renaissance brought us into modernity.

But I find this period fascinating. To answer your question, there’s a through line in the siege of Constantinople that has everything to do with technology and innovation, with Orban’s guns being a great example of it. The Ottomans and the Arabs before them had broken their teeth on the walls of Theodosius for years and centuries. The reason Constantinople was able to survive, despite the protracted state of decadence of the Byzantine Empire, was because they were surrounded by water on three sides and these impregnable walls on the other.

But Mehmet realized that this innovation could smash through those walls. Beyond that, Mehmet literally dragged his fleet out of the water, over the mountains, and brought it down into the Golden Horn — it’s amazing. I traveled to Istanbul many times in my last job with Senator McCain, and I regret that I only appreciate all of the history now in retrospect. I’m very eager to go back.

Jordan Schneider: There’s a really good military museum, actually. It has the chain that blocked the Golden Horn, it has the Orban cannons…

Chris Brose: The panoramic painting of the whole siege...

Jordan Schneider: I was there on my honeymoon. I told my wife, “Can I just get one day to look at the war stuff?”

Chris Brose: Did you hike the wall?

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, you can walk on the side inside. The amount of stuff is incredible. You have some Roman stuff, you got the Byzantines. The mosques are spectacular. Hagia Sophia is overcrowded and a bit much. But the tier-two mosques, you have this experience of serenity of being one of ten people. Shehzade Mosque took the cake for me.

Chris Brose: It’s so fascinating. Everybody thinks, well, in the year 476 the Roman Empire just disappeared. No, it actually went on for another thousand years in Constantinople.

Jordan Schneider: More cannon lore from Crowley— “The psychological effects of the artillery bombardment on the defenders were even more severe than its material consequences. The noise and vibration of the mass guns, clouds of smoke and shattering impact on stone dismayed seasoned defenders. To the civilian population, it seemed a glimpse of the coming apocalypse.” Which one of your platforms is most likely to give us a glimpse of the coming apocalypse?

Chris Brose: I don’t think that we will be giving anybody a glimpse of the apocalypse. We’re certainly not building anything on the order of Orban.

Jordan Schneider: You’ve got to aim higher, man. I’m a little disappointed in that answer.

Chris Brose: But to the question of striking fear into the hearts of our adversaries, the work that we’re doing undersea — we’re building a large diameter and an extra-large diameter autonomous undersea vehicle. We have a phenomenal partner and program in Australia working with the Australian Navy on that. That is an incredibly cool and deeply scary system.

It’s electric-powered, it’s super silent. It can show up in places that are a long, long way away from where it went into the water. It’s wildly accurate, carries all kinds of very interesting cash and prizes. This is the kind of offsetting advantage that I would hope gives our adversaries pause. Every morning, they’d wake up and be thinking, “This isn’t the kind of day that I want to make a run at a US ally or partner or US interest or something else that we value.”

When AI is a Double Agent

Jordan Schneider: All right, I have a weird one — we’ve talked about mass precision. We have precise mass. I have this vision of mass intimacy. AI is coming. We talk to it all the time. And it is growing into less of just like Microsoft Word and more of a companion to lots and lots of people. The espionage and social engineering power that you could have by controlling a decent percentage of a nation state’s therapists, spouses, or best friends just seems wild and just as scary as a secret silent submarine.

Chris Brose: Absolutely. These are the kinds of things that sound like science fiction. Let’s say hypothetically that an adversary of the United States stole an enormous amount of classified information about people in the United States government who hold security clearances. They have a deep knowledge of who people are. Let’s say they have an active cyber campaign and operation to gather more of that information. They can build an AI agent that is capable of identifying and making contact with a person and, over a period of time, becoming intimate with them such that that person begins divulging information about themselves that is compromising.

This isn’t crazy at all. I would be surprised if it isn’t happening. These are incredibly precise, very strategically important, highly consequential types of operations that previously would never have really been possible. This is here now.

To your point about our increasingly intimate relationship with AI and AI agents, it’s only going to become more that way. The nefarious weaponization that is possible with those types of things — I don’t even think we’ve scratched the surface in terms of the level of creativity that people are going to put against this.

Jordan Schneider: Would I rather have an SF-86 or someone’s ChatGPT logs? ChatGPT logs every time. The SF-86 is a point in time. It’s everything you are willing to tell the government. But whatever problems you have in your life, in real-time, you are engaging with technology with those things nowadays. And by the way, 30% of the US AI companion market is currently owned by Chinese companies. We’ll see how that one plays out. If you’re worried, if you think TikTok is sketchy, there’s a bigger worry than just getting the assistant secretary of whatever’s stuff. You can do societal-level things.

Chris Brose: It’s absolutely “both and.” People have become more familiar with threats posed by platforms like TikTok or deep Chinese involvement in American technology and access to our daily data. When you consider things most Americans don’t think about — how this changes intelligence gathering, cultivating assets, and compromise — it’s an incredibly powerful tool.

The amount of information we put into the digital environment and our willingness to become intimate with systems that understand us deeply, that know how to exploit things we’d only share in intimate relationships — that’s all pretty terrifying. They know what to look for.

The Courage to Be Serious

Jordan Schneider: What’s the book that needs to be written? What would the Kill Chain sequel look like? New chapters?

Chris Brose: Writing Kill Chain was uniformly awful. I was working full-time at Anduril with a wife and two kids, writing in my free time on an aggressive ten-month schedule. It was just pain and suffering. I’m fortunate I don’t have to write for a living. I’m not currently working on another book and am probably looking to keep it that way.

What’s the book that needs to be written? There are plenty, but we’ve said all these things already. We know the problems, we know what’s wrong, we have an increasingly clear view of the threat. Washington gets caught up in process questions and mistakes changing a process for better outcomes. JCIDS was consigned to history and we’re better off for it, but nobody should think eliminating a process inherently gets better outcomes.

Jordan Schneider: Things still need to be joint somehow, right?

Chris Brose: I’d submit that we have absolutely everything needed to do what we say we need to do. All the authorities, plenty of money, phenomenal people, world-leading technology. There’s nothing missing. There’s no process, budgetary, or other roadblock standing in our way.

We’re fundamentally limited only by our imagination, will, and seriousness to conceive new capabilities and ways of organizing. It’s just a matter of senior leaders making their institutions do new things rapidly. There’s nothing standing in the way of our doing that.

It’s not to say more books, articles, and podcast don’t need to be published. It’s important to keep people focused on this. But too often, people want to believe that unless we reform procurement or change budgets or fix DoD funding, we can’t change. That’s almost a cop-out. It’s scarier when people realize they have everything needed to do what they say is important. Which begs the question: what are you going to do?

Jordan Schneider: I feel like not a lot of people would agree with you. Why do you believe that?

Chris Brose: I’ve participated in lots of reform, and I know a lot of the authorities that exist. In the Senate, we produced hundreds of pages of acquisition reform. I’m not sure how much was even needed.

When you look at the massive flexibility that exists for the government to acquire what it wants, it often comes down to political will. You could use that authority, but it’s risky, it’s hard. Someone won’t like it. Someone might protest. That doesn’t mean you can’t do it.

Too much of our defense world relies on a priesthood claiming magical knowledge of procurement. Senior leaders have disempowered themselves. A lawyer says you can’t do something. Then you ask them to show you the statute that says you can’t. If they can’t show it to me, I assume I can.

We have enormous authority to create new programs, field new technology, and scale it up. We obviously have talent and technology. We’re spending nearly a trillion dollars on defense annually. You should be able to build a damn good military for that.

I’m not sitting here saying we need to cancel all the traditional programs. We need both, the traditional ones and new, non-traditional, low-cost, mass-producible systems. We have the budget for all of it. If we don’t do this and keep pouring money into old programs, we’ll spend everything without significant increases in capacity or capability. And we will only put ourselves at greater risk in the future.

McCain Memories

Jordan Schneider: The reason things are not happening might come down to this very moving end of The Kill Chain, where you talked about John McCain, who you worked for for a long time, passing, and how dejected you felt.

“The same pessimism occupied me on my third occasion when my emotions about McCain overwhelmed me. It was an overcast and unseasonably cold October morning in Annapolis, Maryland, where McCain’s final resting place lies in a small cemetery on the coast of Chesapeake Bay at the US Naval Academy. It was the first time I had been back to his grave since his death. And it did not take long for all those old emotions and feelings of gratitude to come rushing back. But what was different this time was the overwhelming sense of sadness at the inescapable realization that things in Washington had not gotten any better since McCain’s passing. Indeed, they had gotten worse. Significantly, inexplicably, undeniably worse.”

Chris Brose: That was what I felt at the time. To put some context around it — when McCain passed, I had this hope, primarily when we were sitting at the National Cathedral at his funeral, that maybe this would help to galvanize a critical mass of people to say, “Hey, this guy had worked for literally decades to try to make these processes better, to try to make the DoD better, to make programs perform better, ultimately to get our warfighters the capabilities they need to deter conflict and win.”

I hoped maybe his passing would galvanize people to get their act together—stop fighting over budgets, continuing resolutions, government shutdown threats. All these costly, time-wasting distractions from arming our warfighters.

Part of me knew that wouldn’t happen — politics builds up cynicism. When I visited his grave a year later, I realized that moment of unity, reflection on his legacy, hadn’t led us to be more serious about hard decisions. When I went back up and visited his gravesite a year or so later, I realized, “Man, there was this hope, this moment that maybe we could have had where everyone was united, everyone realized and was reflecting on this guy’s legacy and what he did.” He wasn’t perfect, but he was way better than the rest. I hoped his memory would lead us to be more serious and make hard decisions.

The thing that I get asked about a lot with McCain, what was it like working for him? What was different about him? There are plenty of smart people in Washington. There are tons of decent and hard-working people. There aren’t a lot of courageous people. There aren’t a lot of people who are willing to take an action or a decision knowing that it is going to blow back on them, knowing that despite it being the right thing to do, they are going to suffer an immediate political or other type of consequence for their action. I don’t see that a lot.

That’s what these times call for. I hoped people would be more courageous about hard votes and decisions that let us function like a normal country. We’ve defined deviancy down so much. We’re just trying to get back to normal. Maybe we could have the courage to do that.

At the time that I was writing, the political uncertainty, volatility, and fighting were worse even than they had been when I left the Senate. Five years later, there are bright spots, but until we do more of what we say we need and stop doing unserious, detrimental things that tie our warfighters’ hands, it’s hard to believe we’ve reached a level of seriousness McCain would be happy with.

Jordan Schneider: For young listeners with little McCain memory, what else should they know?

Chris Brose: Watch his concession speech. When people didn’t want him to concede, wanted to keep fighting, he gave an incredibly moving statement about unifying as a country to solve real problems. He said, “It’s time to move on. It’s time to unify as a country and go solve the real problems that matter. We’ve fought over our differences. Now it’s time to focus on governing and moving into the future.”

The thing that was always cool was that he would do all the meetings, he would do all the work, but he always left time to do something fun and interesting and generally culturally and historically significant. On the many trips we made to Istanbul, we saw a lot of amazing history in that city. We went to Mongolia, had a long meeting with the president of Mongolia, who then invited us to go fishing out in the Mongolian steppe. We sailed down the river, paddled down the river with his security detail, and caught fish.

I’ve sat in a lot of meetings in my time in government. Meetings are meetings, and whether you’re working for this principal or that principal, they’re not wildly different. It’s those experiences that McCain always sought out — to do something interesting, to see something significant, to go to a place that he’d read about and see in person. Places that I know I’ll never go back to. I feel incredibly fortunate that I got to do that with a person like that.

Jordan Schneider: Last one for you. What’s the more ambitious version of ChinaTalk? What can I be doing better or bigger?

Chris Brose: What you’re doing is important. For those of us who are not as expert in China, who don’t spend as much time thinking about it, it’s a phenomenal service and resource with the diversity of guests you bring on and the focus and deep level of insight you provide. What’s bigger and better than that? I don’t know. You could get a primetime talk show. You could expand from China to Russia. I don’t think these are things that you necessarily want to do, but what you’re doing is terrific. Honestly, I wouldn’t mess with it because it’s working.

I’m sure you know, but the audio is only on the right channel for Christian. Sounds weird on headphones. 🎧