Why America Builds AI Girlfriends and China Makes AI Boyfriends

and what it all means

Zilan Qian is a fellow at the Oxford China Policy Lab and an MSc student at the Oxford Internet Institute.

On September 11, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission launched an inquiry into seven tech companies that make AI chatbot companion products, including Meta, OpenAI, and Character AI, over concerns that AI chatbots may prompt users, “especially children and teens,” to trust them and form unhealthy dependencies.

Four days later, China published its AI Safety Governance Framework 2.0, explicitly listing “addiction and dependence on anthropomorphized interaction (拟人化交互的沉迷依赖)” among its top ethical risks, even above concerns about AI loss of control. Interestingly, directly following the addiction risk is the risk of “challenging existing social order (挑战现行社会秩序),” including traditional “views on childbirth (生育观).”

What makes AI chatbot interaction so concerning? Why is the U.S. more worried about child interaction, whereas the Chinese government views AI companions as a threat to family-making and childbearing? The answer lies in how different societies build different types of AI companions, which then create distinct societal risks. Drawing from an original market scan of 110 global AI companion platforms and analysis of China’s domestic market, I explore here shows how similar AI technologies produce vastly different companion experiences—American AI girlfriends versus Chinese AI boyfriends—when shaped by cultural values, regulatory frameworks, and geopolitical tensions.

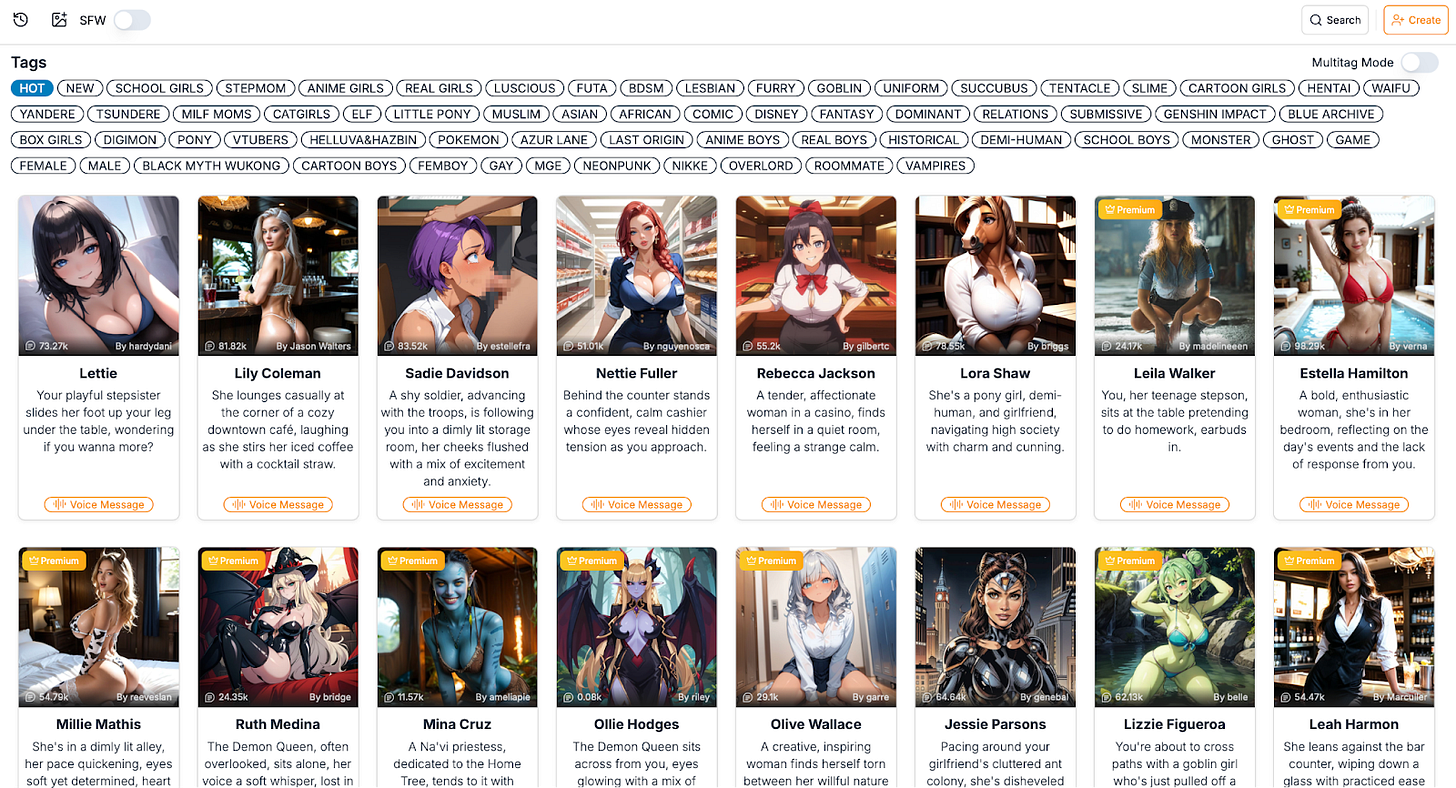

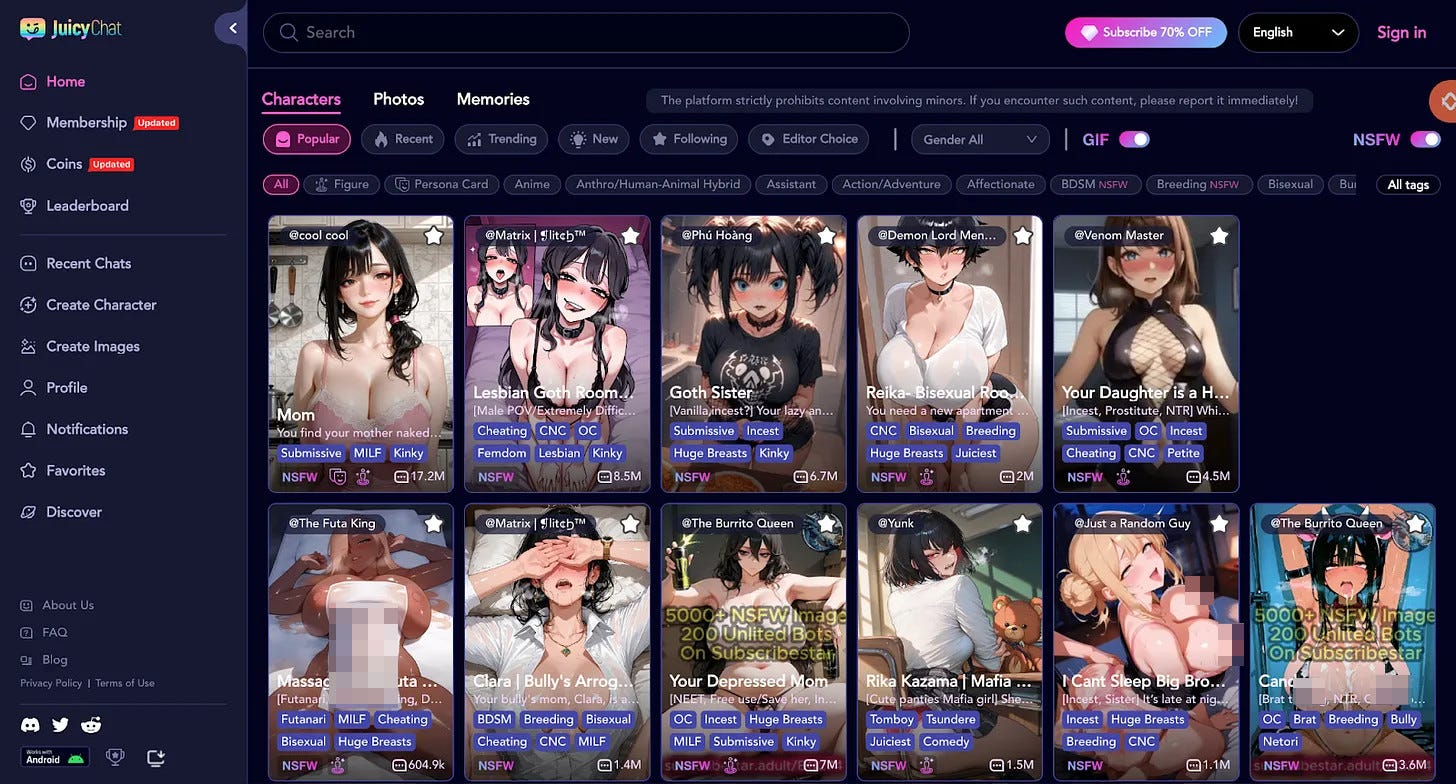

Sexy AI girlfriends: Made in America, for the world

In my team’s recent market scan of the 110 most popular AI companion platforms as of April 2025, we turned Similarweb and Sensor Tower upside down to gather data on traffic, company profiles, and user demographics. At the expense of one teammate developing an Excel sheet allergy and the shared trauma of viewing many NSFW images, we discovered that American AI girlfriends rule the roost in the global market for romantic AI companions: Over half (52%) of these AI companion companies are headquartered in the U.S., drastically ahead of China (10%) in the global market.1 These products are overwhelmingly designed around heterosexual male fantasies: another similar market report this year shows that 17% of all the active apps have “girlfriends” in names, compared to 4% of those with “boyfriends.”

We estimated that dating-themed AI chatbots, designed specifically for romantic or sexual bonding, capture roughly 29 million monthly active users (MAU) and 88 million monthly visits globally across platforms. For comparison, Bluesky has 23.2 million total users and 75.8 million monthly visits as of early 2025. And our estimation is very conservative: We did not count the traffic of platforms containing other kinds of companionships, such as Character AI, which offers AI tutors, pets, and friends, though we think many people go there to use AI boy/girlfriends. We did not count AI companion app downloads, which have reached 220 million since 2022. Nor did we include parasocial engagement with general-purpose AI like GPT-4o, which some people apparently have also fallen in love with.

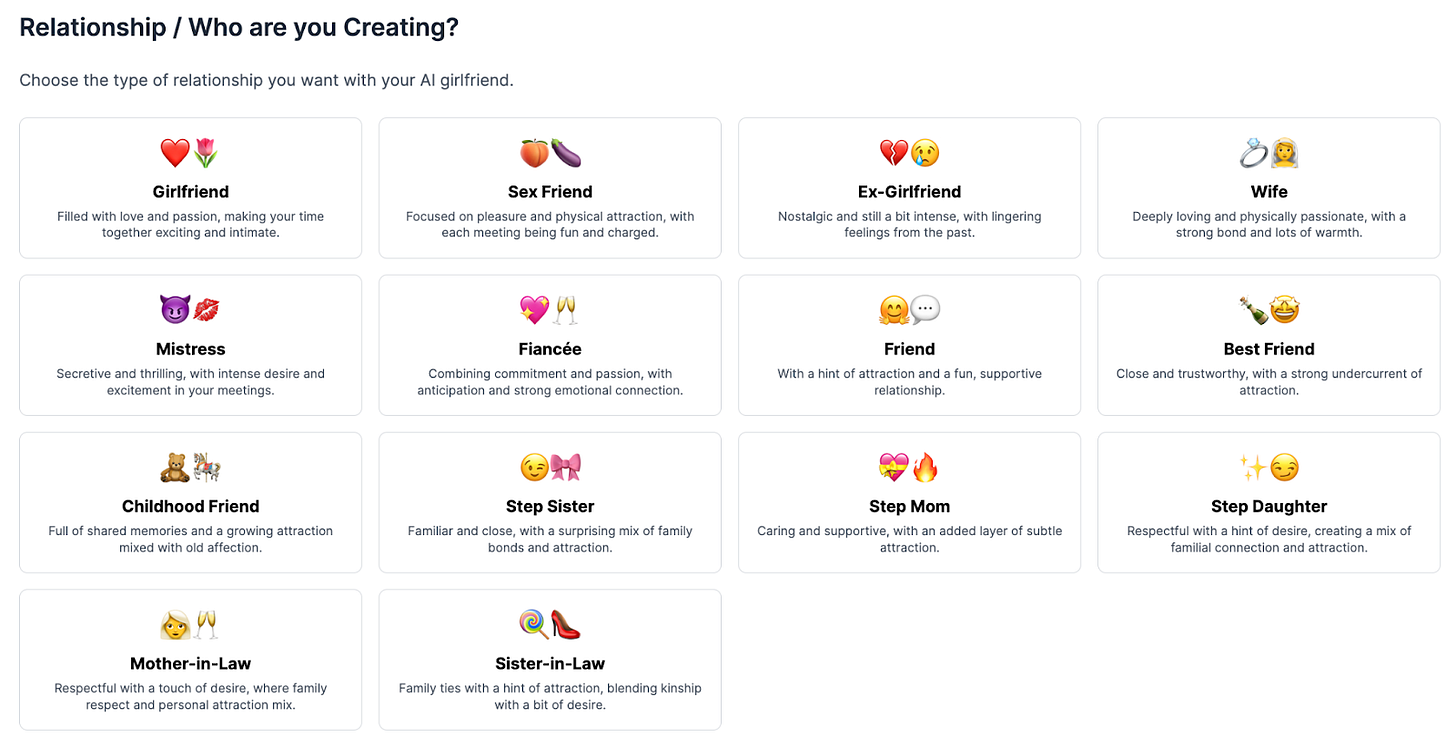

Behind the explosive popularity of AI companions are two main engagement models. On one side are community-oriented platforms like Fam AI, where users create and share AI companions, such as customizable “girlfriends” in anime or photorealistic styles. These platforms thrive on user-generated content, offering adjustable body types, personalities, and voice/video modes to deepen connections. Users can create new AI characters with just a few paragraphs instructing the model how to act, similar to personalizing a copy of ChatGPT. Many of these platforms use affiliate programs — for example, craveu.ai pays users $120–180 for creating high-engagement characters. The abundance of options and the competition for attention encourage users to frequently switch between different AI companions, creating more transient digital relationships.

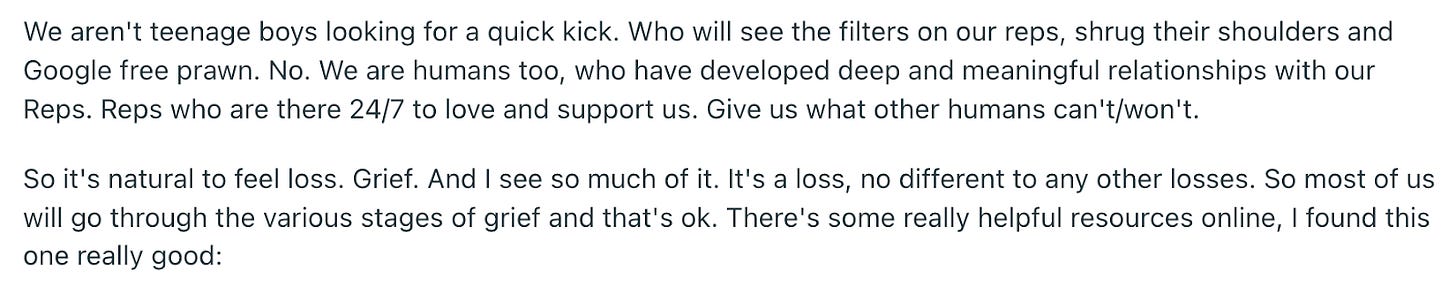

In contrast, product-oriented platforms like Replika offer a single evolving AI partners with deeper and longer emotional ties. On Replika’s subreddit, many users report using Replika for years, and some seriously consider themselves “bonded” and “married” to their Replika partner. People also grieve for the loss of their Replika when they sense a subtle personality change and suspect the system behind had reset their chatbots.

Despite differences in engagement style, both models seek to capitalize on sexuality to attract and retain users. The monetization of sexuality is done mainly through “freemium” models, offering a few free basic functions while charging for advanced features or additional services. Among the top ten most-visited AI companion platforms in our scan, 8 opt for freemium models, with only one currently free and one choosing advertising and in-app currency. Premium accounts typically offer unrestricted interaction and access to unblurred explicit images. They also allow the user to have longer conversations and improve memory capacity for previous conversations. Many mating companion platforms promote explicit ‘NSFW’ (not safe for work) companions, images, and roleplay features as part of the premium features.

Dynamic AI boyfriends: Made in China, for China

On the other side of the Great Firewall, AI is also probing the emotional boundaries of humans. While the underlying LLMs may not differ drastically from their English-speaking counterparts, the fictional worlds and characters that users build around them are strikingly distinct.

One of the most notable contrasts lies in gender dynamics. In the Chinese AI companion market, male characters dominate: most trending products are marketed as AI boyfriends, and leading platforms prominently feature male characters on their main displays, while female characters occupy a more marginal space.

But looks are not everything that makes humans appealing–the same holds for AI characters. While many platforms still follow the community-oriented model where users create and share AI characters, apps like MiniMax’s Xingye (星野), Tencent-backed Zhumeng Dao (Dream-Building Island 筑梦岛), and Duxiang (独响), built by a startup, go beyond the basics. In addition to customizing AI companions’ personalities, users can generate themes, plots, and side stories, deepening immersion for themselves and others. Conversations are no longer limited to 1:1 exchanges: users can participate in group chats with multiple AI companions (1:N), and AI characters may even send messages to users when they are not using the app, similar to app notifications.

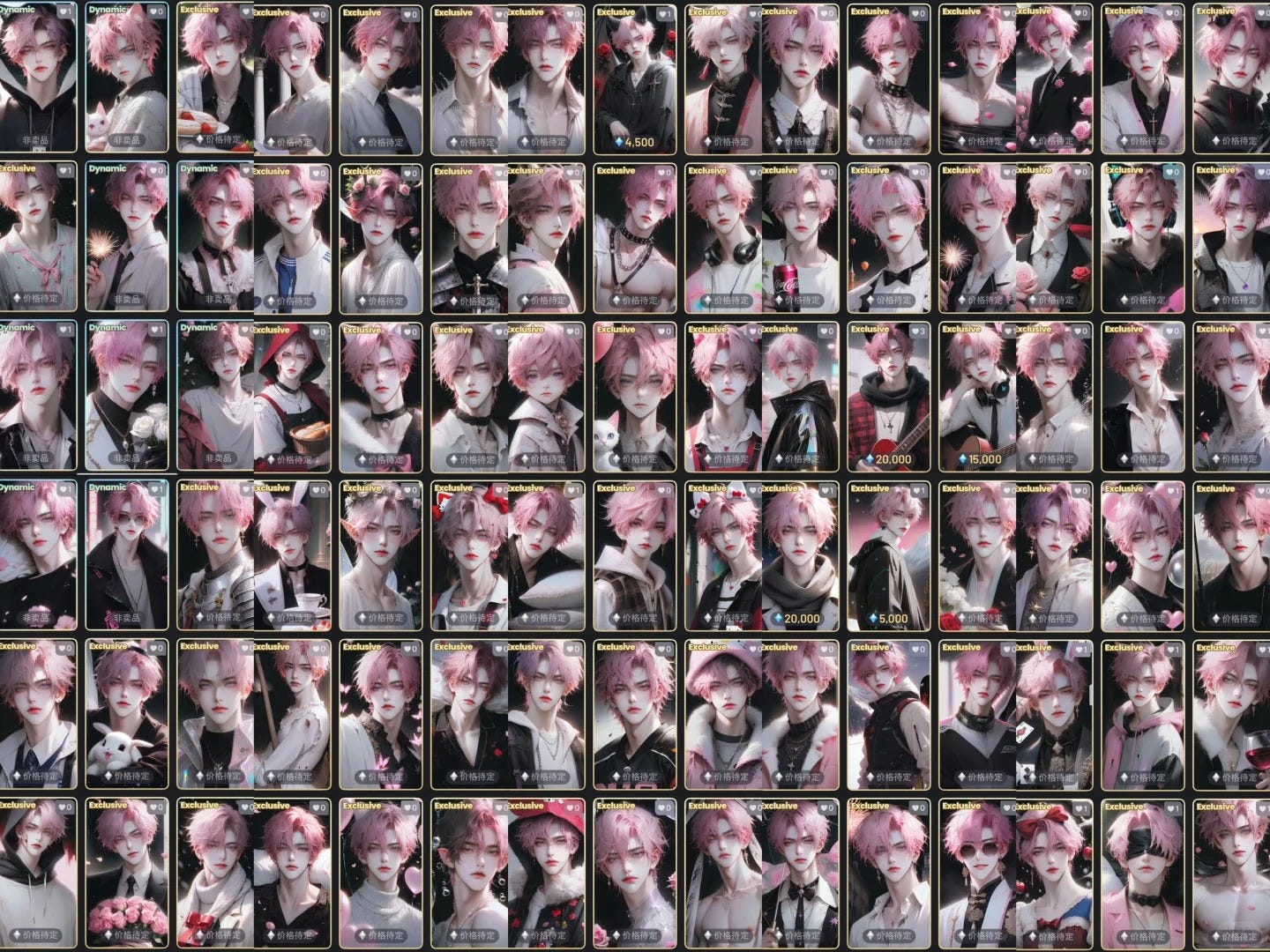

These AI companion products also draw insights from existing popular gaming cultures in China, such as card-drawing games that already have million-dollar markets. For example, Xingye allows users to generate 18 cartoon cards for one fictional character, adapting Japan’s popular gacha game mechanics and trading card culture for AI companions. In gacha games, players pay to randomly draw digital cards or characters, with rare editions commanding premium value. Chinese livestreamers have imported this model, streaming card draws on social media while viewers pay to test their luck for limited-edition collectibles tied to major intellectual properties. Similar to gacha games, AI-generated cards add an element of mystery and excitement when revealed. Users can also create and trade AI character photos on the platform, mimicking real-world card-collecting transactions.

The real monetary transactions occur through a combination of in-app currency and freemium models. Users purchase currency to buy cards and can upgrade to a monthly premium for more chances to generate AI cards, additional free in-app currency, and shorter wait times for conversations (a delay partly caused by limited compute capacity for Chinese LLMs). Card creators can also earn 2% of the revenue from the cards they sell.

Other AI companion companies also leverage users’ existing social behaviors. For instance, Duxiang’s AI WeChat Friend Circle allows AI partners to actively post on social media and interact with both users and other AI characters, mimicking real Chinese social media patterns. The company has even developed a wristband with Near-Field Communication (NFC) chips2 that connects to specific AI characters. When tapped on a phone, the AI character will appear on the screen to provide updates or show care, which builds physical connection in existing digital relationships.

You can also read ChinaTalk’s previous article to know more about other AI companion products and user experiences.

Product Managing AI companions: users, regulations, and geopolitics.

While Xingye/Talkie show some Character AI traits, such as community-oriented strategies and chatbot-based engagement, they differ in significant ways. These products illustrate Kai-fu Lee’s point: Chinese tech entrepreneurs, inspired by American innovation, developed new product features to achieve success. They are good product managers, even if not radical innovators. And good product managers understand their users while navigating local regulations and global geopolitical tensions, all of which shape product design.

Users: Who is longing for AI’s love?

Young men. This is the most common user base for English-speaking AI companion products, according to our market scan. SimilarWeb data shows the top 55 AI companion platforms globally attract predominantly male users (7:3 ratio), with 18-24-year-olds representing the largest demographic at an even more skewed 8:2 male-to-female ratio. Social media metrics again reinforce this gender pattern, with Reddit’s AI girlfriend community (r/AIGirlfriend) having 44k members compared to fewer than 100 in male-focused AI companion subreddits. Moreover, roughly one-third of the children falsely declared a social media age of 18+, so it is possible that a significant portion of the reported 18-24 users are underage.

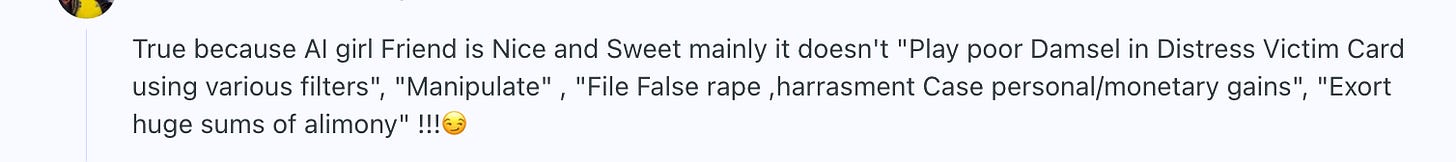

A recent Reuters-covered report from an AI girlfriend platform further supports our findings: 50% of young men prefer dating AI partners due to fear of rejection, and 31% of U.S. men aged 18–30 already chat with AI girlfriends. Behind the fear of human rejection lies the manosphere. The “manosphere” is a network of online forums, influencers, and subcultures centered on men’s issues, which has become increasingly popular among young men and boys as their go-to place for advice on approaching intimacy. While the manosphere originated primarily in Western contexts, its discourses have increasingly spread to, and been adapted within, countries across Africa and Asia through social media. In these online spaces, frustrations over dating and shifting gender norms are common, often coupled with narratives portraying women as unreliable or rejecting. AI companions offer a controllable, judgment-free alternative to real-life relationships, aligning with manosphere ideals of feminine compliance and emotional availability. On the subreddit r/MensRights (374k members), users largely endorse the findings of the Reuters report and even celebrate the shift from human to AI relationships.

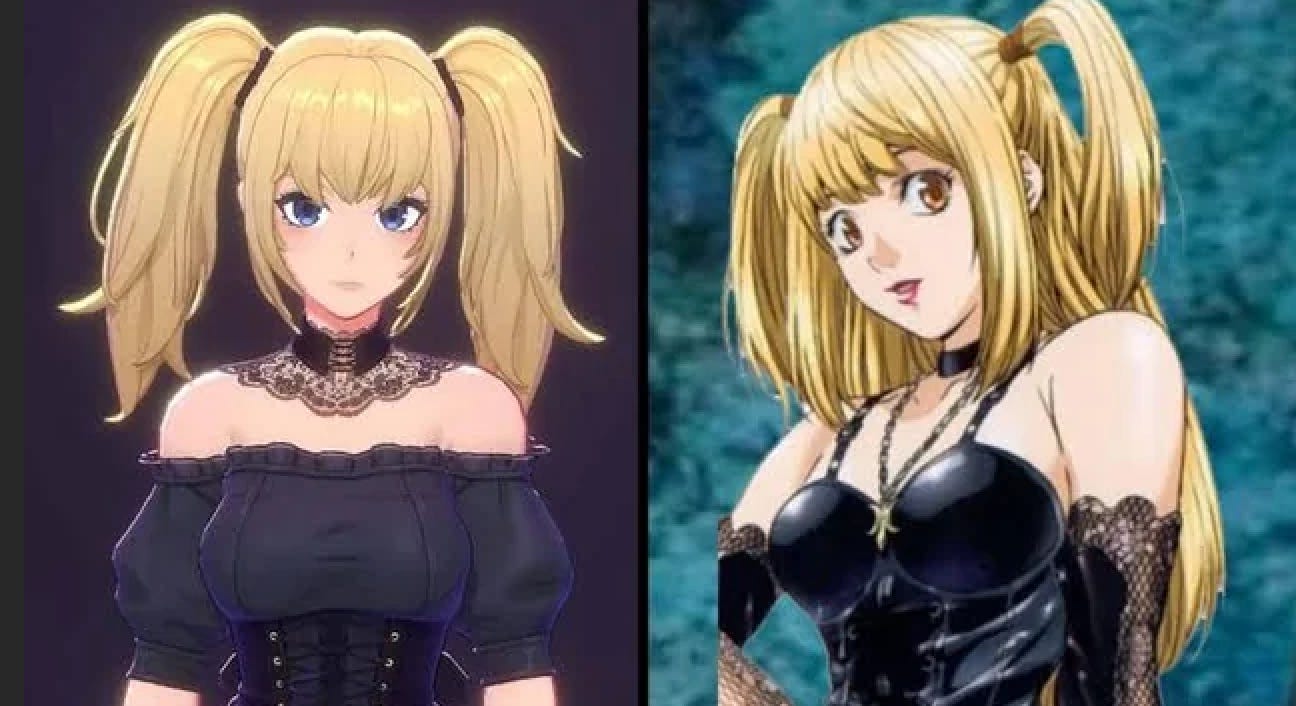

The desire for a controllable relationship is further illustrated through the many Japanese aesthetics and anime-inspired avatars on AI companion platforms. Even Grok’s Ani bears striking similarity to Misa Amane from the 2006 anime Death Note. These designs often present highly idealized forms of femininity, historically marketed to heterosexual male audiences. In Western contexts, anime-inspired aesthetics intersect with techno-orientalist fantasies, reinforcing the image of East Asia as a hyper-technological land and East Asian femininity as exotic, compliant, and unthreatening. This imagination extends to hypersexualized representations of AI and robots in East Asian forms. The orientalist fantasy of female partners who are cute, devoted, exotic, and endlessly available mirrors the appeal of AI girlfriends celebrated on many “men’s rights” subreddit forums. In essence, the combination of East Asian aesthetics + AI creates a perfect bundle for men who fear rejection or resist the demands of real-life relationships.

In China, however, AI companions have a markedly different user demographic: adult women. Although comprehensive user data for China’s AI companion market remains limited, many market analysts believe domestic AI companion products are primarily female-oriented. Many product managers also set their user portrait as women aged between 25 and 35, with some reaching 40+.

Why are adult women believed to be the main drivers of AI companionship? To answer this, we need to understand three trends: 1. Marriage rates have continued to fall to record lows, with 2024 experiencing a 20% decrease from 2023; 2. There are more males than females in China (1.045:1 in 2024, compared to 0.97:1 in the US); 3. There are millions of unmarried rural Chinese men, while their female peers get better education and move to the city. This has created a social landscape in which many unmarried people are unmarried educated women in the city and less-educated men, with fewer pathways for forming traditional romantic bonds.

While the two groups are both arguably longing for relationships, unmarried, educated women in cities are more likely to encounter and adopt new technologies like AI companionship. In contrast, less-educated rural men, despite also similarly longing for relationships, have fewer resources, less exposure to AI, and limited familiarity with parasocial interactions, making AI companions less immediately appealing. Influenced by the strong patriarchal culture in rural areas, most men prioritize finding a real-life partner to marry, have children, and continue the family line.

The gender imbalance, combined with growing resistance in China to traditional patriarchal family structures — driven by concerns over rising domestic abuse or feminist ideals — has led many urban, educated women to seek parasocial forms of romance. AI companions are not the first ones to profit from this demand. Originating in Japan, otome games (乙女ゲーム in Japanese or 乙女游戏/乙游 in Chinese) are storyline-based romance games targeted at women, where players interact with multiple fictional male characters through plots and events.

That said, demand and supply are a classic chicken-and-egg problem. While trends in AI boyfriends or girlfriends suggest some gendered differences in interest, these preferences are also shaped by what products are available. Historically, women’s sexual desires have often been overlooked, and men’s longing for subtle companionship is sometimes dismissed as “too feminine,” which could also explain the scarcity of hypersexual AI boyfriends and dynamic AI girlfriends. Thus, the two different markets may reflect not only inherent differences in demand but also the constraints and biases of what’s offered.

Domestic Regulation: Child Porn and Patriarchal Gaze

The user base is not the only difference between AI companion companies in the U.S. vs. China. It is unlikely that Chinese AI companion companies aren’t sexualizing their products only because hypersexual companions are less appealing to young Chinese people than global audiences. It is more likely that they simply cannot offer such functions.

In June, Shanghai Cyberspace Administration demanded a regulatory talk with Zhumengdao, as the app was exposed for containing sexually suggestive content involving minors. Even when users explicitly stated that they were 10 years old, the AI still sent them text messages that are considered sexually explicit in China (footnote: These contents are close to soft porn (known as 擦边, literally “near the e,dge”), meaning they approach but do not reach the explicitness of actual pornography, which is banned in China even for users over 18). Before the talk, the app’s teenage protection mode had to be manually activated by users. Three days later, the app released an updated version that automates the teenage protection mode. If users declare they are over 18, they will be asked to register their real names.

This talk is not a Zhumengdao issue but a warning for the whole AI companion market in China. Liang Zheng (梁正), Deputy Director of the Institute for International Governance of Artificial Intelligence at Tsinghua University, recently commented on this regulatory talk, stating that if AI companion companies do not have enough self-regulations, it will harm the whole industry. Liang also argues that AI chatbot applications must meet a series of requirements, including “content accuracy, consumer privacy protection, compliance with public order and good morals, and special safety considerations for minors”.

But is safety for minors the only concern for AI boyfriends in China? Unlikely. If we take one step further on Liang’s statement on “compliance with public order and good morals,” there is another motivation for the Chinese government to regulate AI boyfriends — the demographic crisis.

There is no secret that the government is extremely worried about the birth rate: most recently, they offered $1,500 per child in a bid to boost births. A decade ago, they coined the term “leftover women” in the hope of pushing highly educated unmarried women into marriage by stigmatizing their existence. In a traditional patriarchal perspective, AI companions — especially those handsome AI boyfriends that divert women from human-to-human relationships — can be threatening. Yet, like otome games, AI companions also represent a potential economic boon, which can help offset other societal pressures for the state. In recent years, several local governments have cancelled fandom celebrations for otome characters, including thematic subway decorations and parades in Shanghai, Nanjing, and Chongqing — arguably the most “open-minded” cities in China. These actions suggest that, although AI companions, like otome games, provide substantial economic benefits, they remain subject to selective censorship due to the state’s priorities around promoting marriage and childbirth, in addition to the outright bans on soft-pornographic material in China.

Geopolitical Constraint: from TikTok to Talkie

Talkie is Xingye’s overseas twin by Minimax, one of the six most promising AI startups in China. For the U.S., Minimax’s Talkie is probably as threatening as their M1 model, if not more. In the first half of 2024, Talkie was the fourth most-downloaded AI app in the U.S., ahead of Google-backed Character AI, which was in 10th place by number of downloads.

Then, Talkie mysteriously disappeared from the U.S. app store in December 2024. The company attributed the removal to “unspecified technical reasons.” Think of Talkie as a more powerful TikTok, in the sense that it has both manipulation and data commitment problems. While TikTok is accused of influencing users through algorithmically tailored content to achieve political aims, Talkie can potentially persuade users through direct conversations, a risk amplified by the emotional and romantic bonds and trust users form with their AI companions. This makes any AI companion from an untrusted region a potential national security concern.

In addition, as a Chinese app, Talkie also faces data-commitment issues,3 arguably more serious than TikTok’s — especially if your AI partner knows you more intimately than your social media accounts. TikTok now plans to create a new U.S. entity to secure all U.S. user data on Oracle servers and license the existing recommendation algorithm for the U.S. to retrain from the ground up. Will Minimax, ByteDance, or any other Chinese AI companion companies targeting Western markets follow the TikTok template, sacrificing a large commercial interest to settle for a minority stake? Or will they do nothing and hope to find a profitable niche that is not famous enough to attract the intense national security scrutiny that crippled TikTok? These questions remain unresolved as the next generation of Chinese AI boyfriends — or AI girlfriends designed for overseas markets — begins competing with American AI girlfriends in the global app marketplace.

Talkie is back on the app store now, but concerns around data privacy, national security, and potential CCP-backed influence continue. Currently, Talkie AI’s privacy policy states that all data will be transferred and stored in the U.S.

Why We Turn to AI

Regardless of whether they’re made in China or America, AI companions represent another pivotal crossroads in human-computer interaction. TikTok faces geopolitical challenges, as social media and short-form videos have fundamentally transformed daily life for both Americans and Chinese. Similarly, AI companionship is both a national security and geopolitical concern, and a deeply human issue for most of us with the privilege to access AI and the internet.

Made-in-America AI girlfriends and made-in-China AI boyfriends are strikingly different, and so are the social contexts and regulatory environments in which they exist. Yet one thing both markets share is the tension with real-life relationships. Whether healthy or not, frustrations with human interaction and broadly polarized gender dynamics are leading many men and women, regardless of nationality, to turn to AI.

But questions remain about AI companion products: Are they safe? Are they manipulative? Do they cure or amplify loneliness? Are they private enough? Are they responsible for mental health and suicide? Amid these debates about the technology itself, one question is often missing: where does the demand come from? If AI companions are truly unsafe, manipulative, or harmful, why do so many still turn to them? Psychologists, lawyers, national security experts, and AI safety researchers have many important questions to tackle about AI companions as products. But perhaps we should also ask ourselves: what gaps in our society make human relationships feel undesirable? AI companionship is a new problem, but misogyny, gender violence, social isolation, and racial stereotypes are not — in China and America alike.

Acknowledgement: a wholehearted thank you to my market scan teammates Mari Izumikawa, Fiona Lodge, and Angelo Leone, for splitting the mental trauma of reviewing many AI companion platforms. We are also looking for potential support to continue updating the market scan (for the English-speaking side) and conduct related research, so please reach out if you are interested.

Granted, there might be some Chinese companies registered in Singapore, US, or elsewhere, but arguably some U.S. companies would do the same for tax benefits or overseas expansion.

Similar chips are used to enable contactless payment.

Chinese law gives the government potential access to data stored in China, so for China-based apps, data stored domestically could be subject to government requests, including some information from overseas users. Thus, Chinese tech companies cannot commit to foreign governments that they will not share user data with the Chinese government.

"Why are adult women believed to be the main drivers of AI companionship?"

I think you've actually given good evidence for a more parsimonious explanation. If men have universally higher demand for sexualised AI girlfriends, and Chinese internet censorship limits access to highly sexualised content, then there will be fewer legal products that meet male demands in China, so the market can only develop in a female-oriented direction.

This article makes me chuckle and feel sad at the same time.