Ben Buchanan on AI and Cyber

How the White House learned to fear compute

Happy New Year! This is your reminder to fill out the ChinaTalk audience survey. The link is here. We’re here to give the people what they want, so please fill it out! ~Lily 🌸

Ben Buchanan, now at SAIS, served in the Biden White House in many guises, including as a special advisor on AI. He’s also the author of three books and was an Oxford quarterback. He joins ChinaTalk to discuss how AI is reshaping U.S. national security.

We discuss:

How AI quietly became a national security revolution — scaling laws, compute, and the small team in Biden’s White House that moved early on export controls before the rest of the world grasped what was coming,

Why America could win the AI frontier and still lose the war if the Pentagon can’t integrate frontier models into real-world operations as fast as adversaries — the “tank analogy” of inventing the tech but failing at operational adoption,

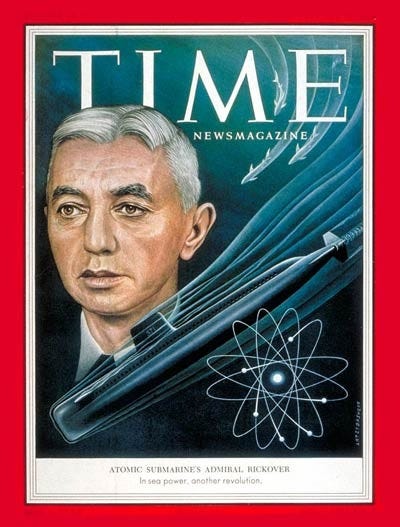

The need for a “Rickover of AI” and whether Washington’s bureaucracy can absorb private-sector innovation into defense and intelligence workflows,

How AI is transforming cyber operations — from automating zero-day discovery to accelerating intrusions,

Why technical understanding — not passion or lobbying — still moves policy in areas like chips and AI, and how bureaucratic process protects and constrains national security decision-making,

How compute leadership buys the U.S. time, not safety, and why that advantage evaporates without building energy capacity, enforcement capacity, and world-class adoption inside the government.

Listen now in your favorite podcast app.

The Biden Administration’s AI Strategy — A Retrospective

Jordan Schneider: We’re recording this in late 2025, and it’s been a long road. What moments, trends, or events stand out to you looking back at AI and policymaking since you joined the Biden administration?

Ben Buchanan: The biggest thing is that many hypotheses I held when we arrived at the White House in 2021 — hypotheses I believed were sound but couldn’t prove to anyone — have come true. This applies particularly to the importance of AI for national security and the centrality of computing power to AI development.

You could have drawn reasonable inferences about these things in 2021: AI would affect cyber operations, shape U.S.-China competition, and continue improving as computing power scaled these systems. That wasn’t proven in any meaningful way back then. But sitting here in 2025, it feels validated, and most importantly, it will continue in the years ahead.

Jordan Schneider: Maybe there’s a lesson here, going back to the 2015-2020 arc. People think many things will be “the next thing.” Was this just happenstance? Was there some epistemic lesson about how folks who identified AI as the next big thing recognized it?

Ben Buchanan: I’d love to say I knew exactly where this was heading when I started exploring AI in 2014-2015. The truth is, I simply found it intriguing — it raised fascinating questions about what technology could achieve. At the time, I was working extensively on cyber operations, which is interesting in its own right.

Fundamentally, though, cyber operations are a cat-and-mouse game between offense and defense — cops and robbers on the internet. That’s valuable as far as it goes, with plenty of compelling dynamics.

But around 2015, I thought, “AI is conceptually driving toward something bigger, forcing us to grapple with questions about intelligence and humanity, with an impact broader than cyber operations.” That’s what drew me in. Once I started digging deeper, it became clear this technology was improving at an accelerating rate, and we could project forward to see where it was headed.

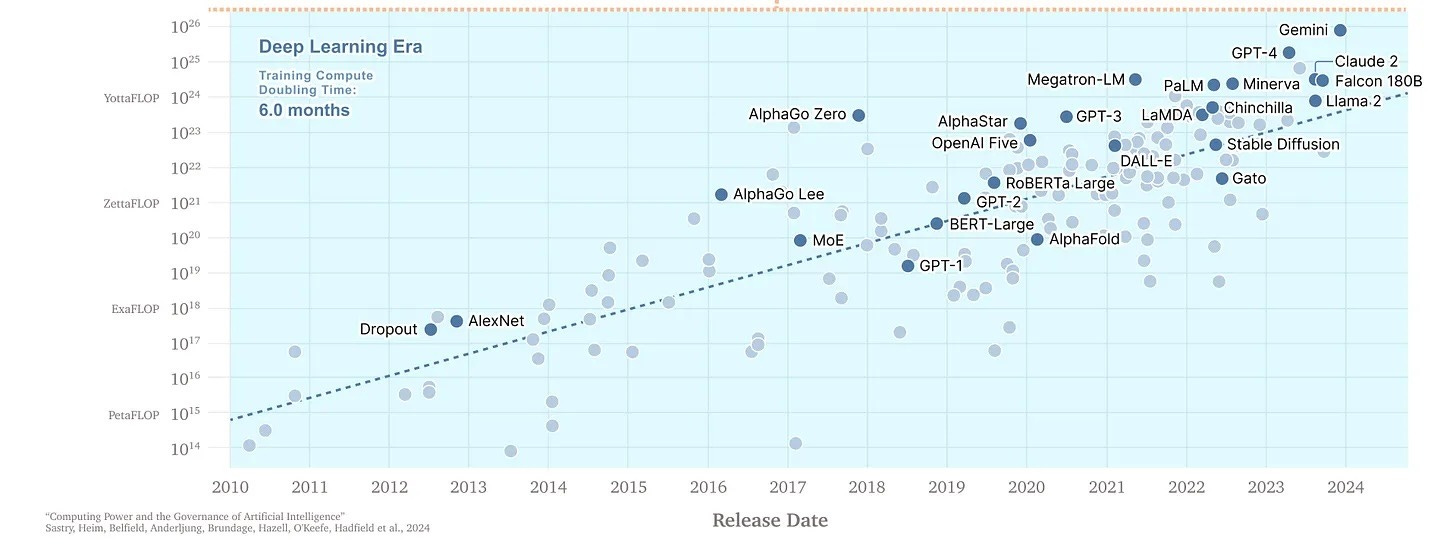

The real turning point came somewhere in the 2018-2020 period when the scaling laws crystallized. That’s when I developed the conviction that AI would fundamentally matter for international affairs and that computing power was the fulcrum. I wrote a piece in Foreign Affairs in the summer of 2020 called “The U.S. Has AI Competition All Wrong,” which argued that we should stop focusing on data and start focusing on computing power. For the past five years, the scaling laws have held.

Jordan Schneider: Can you reflect on how different pieces of the broader ecosystem woke up to AI? This is now a front-page story constantly. Nvidia is worth $5 trillion. The world has caught on, but looking back, different lights turned on at different times. What’s interesting about how that happened?

Ben Buchanan: Probably the strongest technical signal came in 2020 with the scaling laws paper from Dario Amodei and the team that later founded Anthropic. That paper put real math behind the intuition that a few people had about the importance of computing power in rapidly accelerating AI performance.

Then GPT-3 came out in May 2020 — a crazy time in America with COVID and the George Floyd protests. GPT-3 provided even more evidence that you could make big investments in this technology and see returns in terms of machine capability. That was enough for me and others heading to the Biden administration to have conviction about the importance of computing power.

We spent 2021 and 2022 getting the export controls into place. ChatGPT was released in November 2022. Since then, it’s been a parade of even bigger developments. The Kevin Roose article in the New York Times in 2023 brought AI to a new set of non-technical people. The increasing AI capabilities since then have only accelerated awareness.

I’m proud we got some of the biggest actions done before the whole world woke up. When that happened, we could say truthfully, “We’ve already done some of the most important policies here — there’s much more to do, but we’re already taking big steps.”

Jordan Schneider: The CHIPS Act wasn’t necessarily an AGI-focused policy from the start, was it?

Ben Buchanan: I’d differentiate between the CHIPS Act and the export controls. The CHIPS Act is the legislative step — I get no credit for that. Tarun Chhabra and Saif Khan deserve tremendous credit for working on it. That’s not an AGI-focused policy at all. It’s a supply chain policy recognizing that chips are important for many reasons, and we need domestic chip manufacturing like we had decades ago but no longer have. You can reach that policy outcome without believing in AGI or even really powerful AI systems.

On the chip control side, those policies don’t need AGI assumptions to be smart policies. When we justified them, we talked about nuclear weapons, cryptologic modeling, and all the applications possible with those chips before even considering really powerful AI systems. Everything in that justification is completely true. It’s a robustly good action given the importance of computing power — a long-overdue policy independent of AGI considerations.

Jordan Schneider: We had Jake Sullivan on recently discussing the Sullivan doctrine about maintaining as large a lead as possible. But the implementation wasn’t the maximalist version of “as large a lead as possible” regarding controls. Other considerations mediated where they landed in October 2022 and how they evolved over the following years. What are your reflections on bringing these policies to the table?

Ben Buchanan: The process started in 2021 when a small group of us arrived at the White House. Most of us have been on the ChinaTalk podcast before — folks like Tarun Chhabra, Chris McGuire, Saif Khan, Teddy Collins, and myself. We had these convictions about the importance of computing power.

Jake honestly gave us a lot of rope and deserves tremendous credit. At a time when not many people cared about AI — when the world focused on COVID, Afghanistan, Ukraine — Jake and the senior White House staff heard us out. Eventually in 2022, we reached the point where we were actually going to do it.

Everything in government is a slog sometimes, and this was an interagency process. Something like this shouldn’t be done lightly. It’s good there’s at least some process to adjudicate debates. As you mentioned, Jake gave a speech in September 2022 about maintaining as large a lead as possible in certain areas. My view was always maximalist — we should be very aggressive. But I recognize there are many constraints, and someone in Jake’s chair has to balance different concerns that a dork like me doesn’t have to balance. I’m just focused on AI, chips, and technical issues.

Everyone can draw their own conclusions about what we should have done and when. But I’m very proud we got the system to act even before AI became the mainstream phenomenon it quickly became.

Jordan Schneider: The hypothetical Jake entertained was doing the Foreign Direct Product Rule on semiconductor-manufacturing equipment from the beginning. You wouldn’t have this situation where, for example, BIS lists a company with some subsidiary, and one of their fabs is listed, but the fab across the street isn’t. Ultimately, you have this dramatic chart showing semi-equipment exports actually doubling after the controls came into place. Is that the big fork in the road? What else is contingent when looking at how China can manufacture chips today?

Ben Buchanan: On chip manufacturing equipment, the more aggressive option would have been using the FDPR to essentially blanket ban chip manufacturing equipment to China — rather than negotiating with the Dutch and Japanese — the way we did with chips. That’s probably one option.

If we were doing it again, we probably would have been more aggressive earlier on things like High-Bandwidth Memory. Or we would have used a different parameter. The parameter we used in 2023 related to the performance density of chips we would have targeted in 2022.

Anytime you’re doing something this technical, I’d love mulligans to get technical parameters right. But the core intuition and motivation for the policy has held up well, and most of the execution has been good from a policy perspective. I wouldn’t second-guess much of it. I wouldn’t change much except to say I would have loved to do even more, even faster. But that was my disposition throughout this process.

Jordan Schneider: What are the broader lessons? Is the key just “trust the nerds who are really excited about their niche areas”? Is there anything repeatable about the fact you had a team focused on this back when Nvidia was worth a lowly $500 billion?

Ben Buchanan: This is something I thought about in the White House. Jason Matheny asked this question well — “Okay, we found this one. How many other things like this are out there? Can we do this for 10 other things?” We did do something similar eventually in biology and biology equipment.

There probably were others. But there’s also a power law distribution for this kind of thing. The semiconductors, chip manufacturing equipment, and AI nexus were by far the highest leverage opportunities. I’m glad we found it. I’m glad we acted when we did. But I don’t know of another thing at that level of scale. There were probably others at lower impact levels that we could have pursued, and some we did pursue. But this was the biggest, highest leverage move available to us.

Jordan Schneider: What did you learn about how the world works sitting as a special advisor on AI in those final years?

Ben Buchanan: I learned a lot about process. I had this concept that someone — maybe the president — just makes a decision and then it all happens. Anyone who’s worked in government can tell you there’s much more process involved. Some of that process is good, some is annoying, but there’s a mechanism to it that’s important.

I recall a moment when I made some point in a meeting, and someone said, “Well, that’s great, Professor Buchanan, you’ve worked out the theory, but what we’re doing here is practice.” It turns out in many cases, the theory isn’t that difficult. Many of us had written about this in 2019 and 2020 — the theory was worked out long before. But it was still a cumbersome process to get the system to act. Sometimes for good reason.

Jordan Schneider: Why?

Ben Buchanan: I don’t know what the export market was at the time, but we’re talking about a company worth hundreds of billions of dollars — Nvidia. We’re talking about very important technology. We’re talking about essentially cutting off the world’s largest country by population from that technology. Those aren’t things that should be done lightly. It’s fair that there should be a gauntlet to run before the United States takes a decision like that.

Jordan Schneider: What are your state capacity takes after doing this work, in the vein of Jen Pahlka?

Ben Buchanan: There are real questions on enforcement. The best counterargument I never heard to our policies was simply, “The United States government isn’t capable of doing this. Maybe we could write the policies eventually, but the enforcement isn’t there. There will be subsidiaries. The Bureau of Industry and Security in the Department of Commerce, which carries out enforcement, is chronically underfunded.”

I don’t buy that argument. The U.S. Government should do this and could do this. I’m all for building state capacity in basically every aspect of AI policy. When I moved to one of my later roles in the White House — working with the Chief of Staff’s office and the domestic side where I had more control — this was a big priority. We hired probably more than a thousand people in 2023 and 2024 across a large variety of agencies to build that state capacity.

Jordan Schneider: If you had — maybe not 100% but 65% — the level of top cover that DOGE had in its first few hundred days to take big swings without worrying about getting sued two years later. I know you’ll say rule of law is important, but if you had your druthers and things worked out fine, what directions would you have liked to run harder on?

Ben Buchanan: Rule of law is important, but it’s actually easier to burn things down than build them up. We had substantial top cover — Jake Sullivan, Bruce Reed, and ultimately the President gave us top cover at every turn. But on the China competition front, I would have wanted to do more things faster and more aggressively, especially given what I now know about how correct the general theory was.

You mentioned chip manufacturing equipment — that was one. HBM is another that didn’t come till a couple years later. Obviously I would have bulked up enforcement capabilities with that kind of control. Much of that still holds up. The China Committee in the House did a good report maybe a month or two ago on things that could be done on chip manufacturing equipment. Those are robustly good actions. We should be doing them as soon as possible. If we could have done them earlier, that would have been great, but we certainly should be doing them now. That’s in the Trump AI action plan. This isn’t a partisan issue. They just haven’t done it yet. The Rickover Imperative

Jordan Schneider: Setting what Trump is going to do aside, what do you think the federal government is capable of? What do you think the federal government could really do if they put their mind to it?

Ben Buchanan: Wearing my AI hat more than my China hat, the most fascinating question of the moment is, what is the relationship between the public sector and the private sector here? This is a time when you have a revolutionary technology, probably the first one since the railroad, that is almost exclusively coming from the private sector. Nukes and space and all this other stuff, it’s coming from the government. Maybe the private sector is doing the work, but the government’s cutting the check.

This is a question that we just started to get our hands around, but if I had this level of control you’re talking about and I was still in the government, I’d be going to places like DOD and the intelligence community and saying, “You have to find ways to develop this technology and build it into your workflows and take what the private sector has built and really make sure we are using this for full national security advantage.”

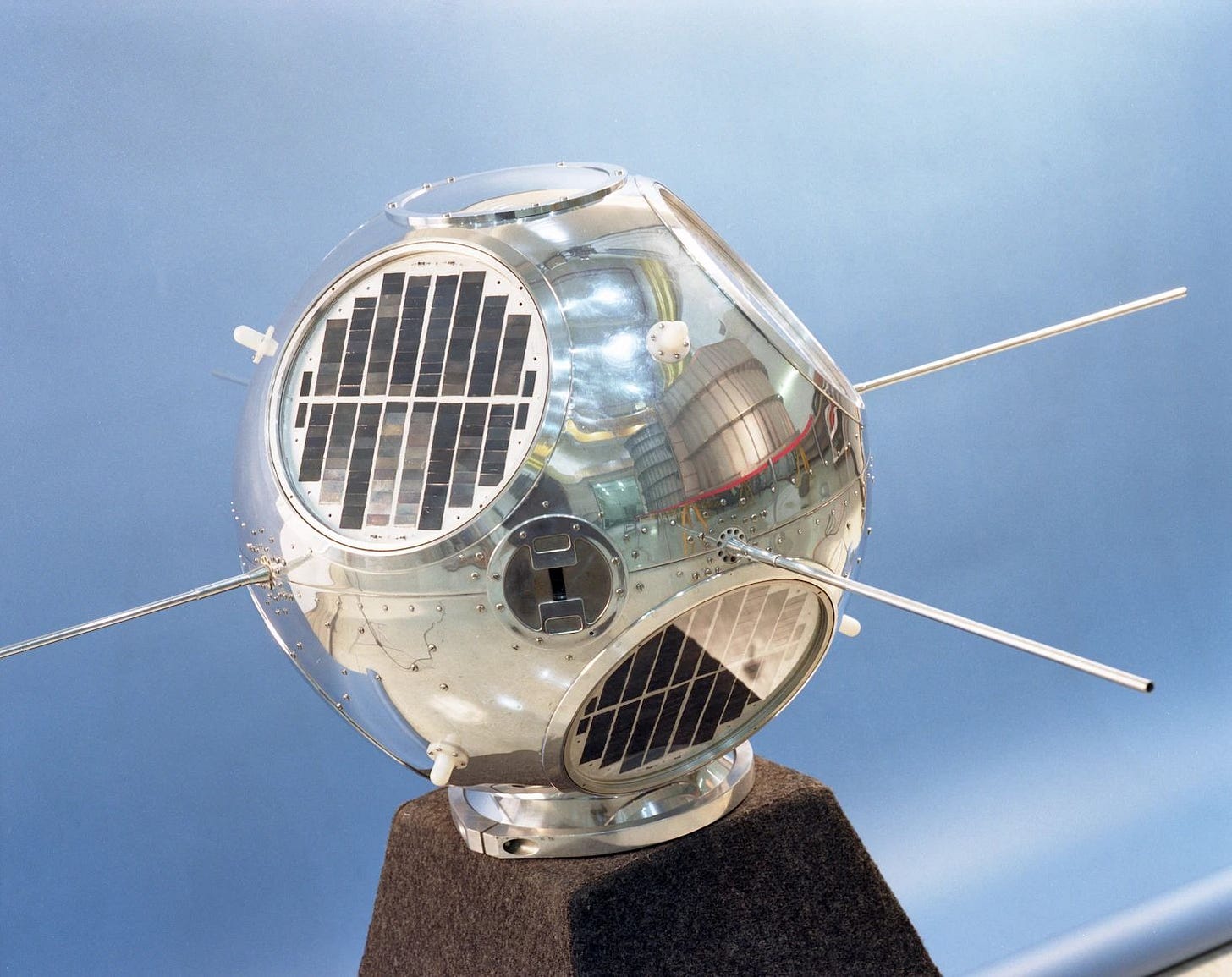

I actually think the analogy there is maybe less like DOGE, though there’s some of that, and more like, who’s the Rickover of this era, and what does that look like? What does the Rickover look like for AI? Someone who’s taking the technology and really integrating it into military operations? The CORONA program and what the American spy agencies did were incredibly impressive, pushing the boundaries of the technological frontier. They basically took early spy satellites and dropped the film canisters from space. It’s just insane that it worked. That’s the kind of stuff that requires a lot of air cover, a lot of money in some cases, and a lot of ambition. I would be really pushing, and we did push to get government agencies to do that kind of work, to have similar levels of ambition, taking a private sector-developed technology and putting it to use for our very important missions.

Jordan Schneider: Are there too many structural bounds on doing Rickover-type stuff for the national security complex as currently established to take those big swings?

Ben Buchanan: As someone who’s never worked in DOD or the IC, I don’t know that I have a high confidence view. But the answer probably is yes. We worked on the President’s National Security Memorandum on AI, and there’s a line in the introduction of that document which says something like, “This is not just about a paradigm shift to AI, but this is about a paradigm shift within AI.”

I think if you go to DOD or you go to the intelligence community, a lot of folks will say, “No, no, of course we do AI. We’ve done AI for a long time. Don’t you know, we funded a lot of AI research in the 1980s?” But really what we’re talking about is, how quickly after Google drops Gemini 3 or Anthropic drops Claude 4.5 can we get that into the intelligence community and DOD workflows, including classified spaces, and put it to use for the mission? How much can we redesign those workflows to accommodate what the technology can do in the same way that, in the early days of the industrial revolution, everyone had to redesign factories to account for the engines and electricity? I’m not saying I’m qualified to do any of that, but that’s where I’d put a lot of focus if I want to benefit American national security.

Jordan Schneider: Private sector firms will be able to outcompete other private sector firms by doing a better job of employing AI and whatever capabilities it unlocks. If that is automating low-level stuff, if that is informing strategic C-suite decisions, then you have a sort of natural creative destruction element going on. As Sam Altman said at one point, “If OpenAI isn’t the first company in the world to kick its CEO out of a job and hand the reins over to AI, then we’re doing something wrong.”

It is inevitable that governments all around the world are going to be slower adopting that than, you know, the five-person startup that’s worth $5 billion because they can be incredibly nimble and are really technically proficient in working at and even beyond the frontier of what is commercially acquirable. But the question is, aside from people sitting in the White House telling agencies to get their shit together, or just being scared of being outcompeted by China or Mexican cartels or whatever, what could the forcing function be to drive some of the legislative and executive branch action to have that stuff actually happen?

Ben Buchanan: There are a couple of points here.

First, the stakes are higher for DoD in the intelligence community than they are for the five-person startup. It is reasonable that, to some approximation, those places would go a little bit slower because we’re dealing with life and death and not cat yoga or whatever the startup is these days.

Second, the forcing function for students of history should be what you said, which is the fear of being outcompeted.

Jordan, you have sent me enough books on World War II over the years to know that the tank offers a very illustrative analogy here and that it was the British and the French who invented the tank in the waning years of World War I. They didn’t really know what to do with it. They didn’t know how to apply it. And then it was the Germans in the early days of World War II who figured out how to use it. And it offers the lesson that, you know, this technology was invented at the end of World War I and it kind of sits dormant, then the Germans pick it up, and then they use it to just roll across Europe with blitzkrieg. I am deathly afraid of that happening in AI, where it is America that invents this technology, the American private sector, but it is other nations that figure out how to use it for national security purposes and create strategic surprise for the United States. That should be the forcing function.

Realistically, you are going to need significant DoD leadership and intelligence community leadership to drive that. I’m worried we’re going in the wrong direction. Laura Loomer got Vinh Nguyen fired. He was the Chief AI Officer at NSA and one of the best civil servants I ever worked with. So I’m worried we’re going in the wrong direction on that front. But I do think that’s the imperative.

Jordan Schneider: The corollary of that, which makes it scarier, is this — America’s lead in compute suggests a world in which we could get away with not doing a good job on the operational level reimagining of intelligence and defense. But there are also many futures in which, even if America ends up having two or three times the compute power, the downstream creativity when it comes to employing that compute for national security purposes is such that you can’t just rest on your laurels of having more data centers. We aren’t just good because Nvidia makes better and more chips than Huawei.

Ben Buchanan: Emphatically not. Even the best defense of our policy to buy a lead or build a lead over China in terms of computing power is to say it buys us time. And then if we don’t use that time, we get zero points. It’s not like, “Oh, well, you get a B-plus because you built the lead and then you blew it.” You still blew the lead.

I view the AI competition with China as coming down to three parts.

The competition to make the best models, the frontier. This is where compute really helps. The private sector is taking the lead.

The competition to diffuse those capabilities out into the world, to win the global market, to win over developing nations and the like.

National security adoption. To say, “Okay, we’re going to take this technology that we’re inventing, that only we are inventing at the frontier, and we’re going to put it to use our national security missions.”

It is entirely possible that we win the lead to the front, we win the race to the frontier. We have success in that competition. But if we don’t get our act together on the national security side, we still fall behind, just as the French and the British fell behind in the early days of the tank.

Jordan Schneider: The other thing folks don’t necessarily appreciate is that if you just win A, or you win part A and part B, it doesn’t solve everything. There are always other moves you can do if you feel like your adversary is winning in this dimension of the conflict, like data. America has 10 times more data centers. What happens when the lights go out? Or what happens when some drones fly into them? I mean, there’s just so much asymmetrical response. To bank your entire future on superintelligence seems like a rather foolhardy strategic construct.

Ben Buchanan: I would never advise a nation to bank its entire future on superintelligence. On the other hand, I would never advise a nation to cede preeminence in AI. Preeminence in AI is a very important goal for a nation and for the United States in particular, and shows up in all parts of economic and security competition. But definitely it’s not the case that, “Oh, we have more data centers and we’ve cut China off from chips. We’re good.” That is the beginning of the competition. It is far from its end.

AI and the Cyber Kill Chain

Jordan Schneider: All right, let’s do a little case study. Your first two books, The Cybersecurity Dilemma, a bestseller, and The Hacker and the State, which we were almost going to record a show on until Ben got a job. They’re all about cyber. What’s the right way to conceptualize the different futures of how AI could change the dynamics that we currently see?

Ben Buchanan: The intersection of AI and cyber operations is one of the most important and one of the most fascinating things I’ve been writing about for a long time. There’s a bunch of different ways you could break it down. Probably the simplest conceptual one is to say we know what’s sometimes called the kill chain — basically the attack cycle of cyber operations — looks like. We know what the defensive cycle looks like. For each of those steps, how can AI change the game?

There’s been so much hype here over the years, and we should just acknowledge that at the outset. But there is a reality to it, and as these systems continue to get better, we should expect the game of cyber operations will continue to change.

You could break that further into two parts. If you look at the offensive kill chain, I think you could say one key piece of this is vulnerability, discovery, and exploitation. That is a key enabler to many, though certainly not all cyber operations. We’ve seen some data that AI companies like Google are starting to have success doing AI-enabled program analysis and vulnerability research in a way that was just not the case a few years ago. The second one is actually carrying out offensive cyber operations with AI, moving through the attack cycle more quickly, more effectively with AI. We can come back to that, but let’s stick with the vulnerability for a second.

When I was a PhD student, a postdoc, DARPA ran something called the Cyber Grand Challenge in Las Vegas in 2016. It was an early attempt to say, “Could machines play Capture the Flag at the DEF CON competition, the pinnacle of hacking?” And the answer was, “Eh, kind of.” They could play it against each other, but they were not nearly as good as the best humans. This was so long ago, we weren’t even in the machine learning paradigm of AI.

Then, when I was in the government and we were looking for things in 2023 to do on AI, I was a big advocate of creating something called the AI Cyber Challenge, which essentially was the Cyber Grand Challenge again. We were saying, “Now we’re in a different era with machine learning systems, what can be done?” DARPA ran that in ‘24-‘25, and I think that told us a lot. There probably is something there about machine learning-enabled vulnerability discovery and either patching or exploitation. That’s probably where I’d start.

Jordan Schneider: Okay, let’s follow your framework. Let’s start on the offensive side of the divide that you gave. What is the right way to conceptualize what constitutes offensive cyber power, and how does AI relate to those different buckets?

Ben Buchanan: At its core, offensive cyber power is about getting into computer systems to which someone does not have legitimate access and either spying on or attacking those systems. A key part of that is this vulnerability research that we were talking about — finding an exploit in Apple iOS to get onto iPhones or in critical infrastructure to get onto their networks.

We are at long last starting to see machine learning systems that can contribute to that work. I don’t want to overhype this — we have a long way to go. But Google has used its AI system called Big Sleep to find significant zero-day vulnerabilities. Now they’re using the systems to patch those vulnerabilities as well. We’re starting to see evidence in 2025 of that kind of capability. It’s reasonable to expect that this is the kind of thing that nations will, if they’re not already interested, will before long be interested in because of how important that vulnerability discovery capability is to offensive cyber operations. That is a key part of national power, insofar as cyber is a key part of national power, getting access to AI systems that can discover vulnerabilities in your adversary networks.

Jordan Schneider: Presumably, this just comes down to talent. Just how many good folks can your government hire and put on the problem?

Ben Buchanan: Before you get to AI, it definitely comes down to talent. These are some of the most important people that work at intelligence agencies, those who can find vulnerabilities. It’s a very, very cognitively demanding, intricate art. Again, I don’t want to overhype it — but the argument goes, “Well, I can start to automate some of that,” and to some degree, that will be true. And to some degree, you’ll still need really high-end talent to manage that automation and to make sure it all actually works.

Jordan Schneider: It’s talent and it’s money, right? Because you can buy them as well. I guess we’re left with a TBD, like we are in many other professions, thinking about to what extent the AI paired with the top humans is going to be more powerful, whether it allows more entry-level people to be more expert, or whether we’ll just be in a world where the AI is doing the vast majority of the work that was previously a very artisan endeavor.

Ben Buchanan: It’s TBD, but there’s also a direction of travel that’s pretty clear here, which is towards increasing automation, increasing capability for vulnerability discovery by machines. And we should expect that to continue. We can debate the timelines and the pace, but I don’t see any reason why it wouldn’t continue.

It is worth saying that it might not be a bad thing. In a world in which we had some hypothetical future machine that could immediately spot insecure code and point out all the vulnerabilities, that would be a great thing to bake into Visual Studio and all the development environments that everyone uses. And then, the theory goes, we’ll never ship insecure code again. It is totally possible that this technology, once we get through some kind of transition period, really benefits the defensive side of cyber operations rather than the offensive.

Jordan Schneider: Staying on the offensive side, though, let’s go to the exploit part. I’m in Ben’s phone. I don’t want to get caught. I want to hang out there for a while and see all the DoorDash orders he’s making. Is that more or less of an AI versus a human game?

Ben Buchanan: Just to make sure we’re teeing the scenario up here — you have a vulnerability in a target, you’ve exploited that vulnerability, you’re on the system, then you want to actually carry out the operation. Can we do that autonomously? We are starting to see some evidence that hackers are already carrying out offensive cyber operations in a more autonomous way. Anthropic put out a paper recently where they attribute to China a set of activities that they say autonomously carried out key parts of the cyber operation.

It’s worth saying here, as a matter of full disclosure, I do some advising for Anthropic and other cyber and AI companies. I had nothing to do with this paper, so I claim no inside knowledge of it, but I think it’s fair to say OpenAI has published threat intelligence reporting as well, about foreign hackers using their systems to enable their cyber operations. There is starting to be some evidence essentially that AI can increase the speed and scale of actually carrying out cyber operations. That totally makes sense to me.

Jordan Schneider: There is a rough parallel between offense and defense — attackers want to find and exploit vulnerabilities, while defenders want to find and patch them. Is there any reason to believe AI will have a different ‘coefficient’ of impact on these distinct phases? Will AI be significantly better at finding flaws than it is at exploiting them, or should we expect these capabilities to develop roughly in parallel?

Ben Buchanan: I think it’ll roughly be in parallel. If we play our cards right, we can get to a defense-dominant world. Because if we had this magic vulnerability finder, we would just run it before we ship the code, and that would make the offense’s job much, much harder. Chris Rohlf of Meta has done good writing on this subject, and has made the case for it most forcefully. But we have to get there.

Best practices would solve so many cybersecurity problems, but no one follows the best practices — or at least, not enough people do. That’s why cybersecurity continues to be an industry, because it’s this cat-and-mouse game. I am cautiously optimistic that we can get to a better world because of AI and cyber operations, offensive and defensive. But I’m very cognizant we’re going to have a substantial transition period before we get there.

Jordan Schneider: Are there countries today that are really good at one half of the equation, but not the other?

Ben Buchanan: There are limits to what we can say in this setting about offensive cyber, but I think America has integrated cyber well into signals intelligence.

Jordan Schneider: I meant the split between finding the exploits and using the exploits. Is that basically the same skill?

Ben Buchanan: I think they’re very highly correlated. If anything, using the exploits is easier than finding them, and finding them is a very significant challenge. There are not that many found per year. But there’s a notion we have in cybersecurity of the script kiddie, someone who can take an off-the-shelf thing and use that themselves without really understanding how it was made. So, yeah, I think that’s the difference.

Jordan Schneider: And then, the net assessment on the defense side?

Ben Buchanan: It’s worth just saying that on the defensive side, huge portions of cyber defense are already automated with varying AI technologies. The reason why the scale of what we ask network defenders to do is so big is that you need to have some kind of machine intelligence doing the triaging. Otherwise, it’s just going to be impossible. This is a huge portion of the cybersecurity industry. It’s a huge portion of things as basic as spam filters and things that are more complex in intrusion detection. The picture you painted before about this race between offense and defense, and both sides using machine learning in the race, I think that’s basically right. It’s even more fundamental to the defensive operations than it is to the offensive side.

Making Tech Policy

Jordan Schneider: Broadening out theories of change for policy. What inputs matter and which ones don’t?

Ben Buchanan: In the current Trump administration or just more generally?

Jordan Schneider: More generally. Well, we’ve already talked about — one is individuals who are really passionate about a thing, get into the government and then convince their principals that their thing is important. But there clearly are other things going on besides staffers’ passions that end up in the policy, right?

Ben Buchanan: You shouldn’t win policy fights based on passion. You should bring some data. On subjects like technology policy, in a normal administration, there is still a lot of alpha in actually understanding the technology, or if you’re in a think tank, teeing up an understanding of the technology for the principal, because it is really complicated. If you’re looking at something like the chip manufacturing supply chain, there are so many components and tools — it’s probably the most complicated supply chain on earth. This is a case where technical knowledge — either on the part of the policymaker or on the part of a think tank author — is just a huge value above replacement. When my students and others come to me and say, “What kind of skills should I develop such that I can make contributions to policy down the line, either in the government or advising the government?” My answer is almost always, “Get closer to the tech.”

Jordan Schneider: It’s kind of a bigger question though. I mean, there’s money, there’s news reporting, etc. but what should you do as an individual? Just reflecting on the way debates have gone over the past five years around this, what is your sense of the pie chart of the different forces that act on these types of questions?

Ben Buchanan: Certainly, other forces include money, lobbying, and inputs from corporations that have vested interests. To some degree, that’s legitimate and part of the democratic process. And to some degree, that can become a corrosion of national security interests. We were able to push back on that a fair amount, and our record shows that. But it’s undeniable that that is a very key part of how the U.S. Government makes its decisions is just the incoming and lobbying from people who have a vested stake in what those decisions turn out to be.

Jordan Schneider: You know, the answer you gave is the one that we want to hear on ChinaTalk, like, “Oh yeah, you just learned the thing, and it’ll be good.” But what else ground your gears then?

Ben Buchanan: Maybe I’m presenting too rosy a view to ChinaTalk, but that was kind of my experience. Again, the process was longer than I would like and so forth, but big companies, Nvidia chief amongst them, were not happy about the policies that we put into place. I get that. But the policy stuck, and there’s becoming a bipartisan consensus on this that even lobbying has not been able to overcome. This is the case where I do think, with important exceptions, the facts have mostly won out, and I think that’s good. Now, there are probably a lot of aspects of national security policymaking where that’s not the case that I didn’t work on. But I feel lucky that I’m speaking about my experience here. And for the most part, my experience has been fair-minded. People in the government heard us out and made the right decision.

Jordan Schneider: What are the other big questions out there? What do you want? What do you want the kids to write their PhDs on?

Ben Buchanan: One of the most important questions at the moment is just how good AI is going to get and when. I see no signs of AI progress slowing down. If anything, AI progress is accelerating. One of the really interesting papers from earlier this year, something called Alpha Evolve from Google, which provided the best evidence we’ve seen thus far of recursive self-improvement, of AI systems enabling better and faster generation of the next generation of AI systems. That is really significant. In that case, the AI system discovered a better way of doing matrix multiplication, one of the core mathematical operations in training AI. No one in humanity expected this. We’ve done matrix multiplications the same way for the last 50-plus years. And this system found a way to do it 23% better. That kind of stuff suggests we are at the cusp of continued progress in AI rather than any kind of meaningful plateau.

Another subject that maybe is a little bit closer to the ChinaTalk reader is energy. You know better than I do the way in which China is just crushing the United States on energy production, which of course is fundamental for AI and data centers. I expected the Trump administration to be much better in this area than they actually were. They talked a very big game. Republicans in general are pro-building and so forth, but Trump has cut a lot of really important power projects, basically because they’re solar projects. Michael Kratsios, Trump’s science advisor, said, “We’re going to run our data centers on coal.” That’s obviously not realistic. That’s another fulcrum of competition with really clear application to AI between the United States and China.

Jordan Schneider: What have you been reading nowadays?

Ben Buchanan: I read a book recently called A Brief History of Intelligence by Max Bennett. It came out a couple of years ago. I thought that was a fascinating book on thinking about intelligence, because it’s not about AI, but basically how human intelligence developed. You can see over hundreds of millions or billions of years, depending on how you count the development of intelligence, you can see how evolution was working through a lot of same ideas that humans had to work through when we were developing AI systems over the last 70 or so years, in some cases picking many of the same solutions to some of the same or similar problems. What is it we’re actually talking about when we talk about intelligence? So much focus is on the artificial part. Let’s put some focus on the intelligence part. That was a great book.

Jordan Schneider: I feel like I would have trusted that book more if it came out in 2020 or 2019. I don’t know the field, and there was a whole lot of, “Oh, look how these models actually worked, just like the organelles.”

Ben Buchanan: I mean, sure, there’s some of that, but I think the bigger point is just put aside the analogy to AI if you want. It’s just a really interesting story of how our own brains developed and how human intelligence developed. I don’t know enough about neuroscience to say — maybe there’s a great rebuttal to it. But I found that history of intelligence development in the biological sense really interesting.

But one question that’s important, maybe for the ChinaTalk reader and analyst, is — what’s the relationship between the Chinese state and the Chinese tech industry? We talked a little bit earlier about how much of a challenge it is to get the U.S. private sector and public sector work together, at least canonically. It is easier for China to achieve that. I would love to know the degree to which that’s true in practice. And to what degree are companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and DeepSeek working with the PLA or working with the Chinese state? Or to what degree are they creating some space for themselves? There was some media reporting a week or so ago. I forget exactly about Alibaba working with some part of the military apparatus. I would love the ChinaTalk treatment of the subject.

Jordan Schneider: I mean, my two cents are, it’d be weird if they weren’t. I mean, it’s fair to say that Microsoft and Google are part of the American military industrial complex in one way or another, at least on the cyber side, to be sure.

Ben Buchanan: On offensive cyber?

Jordan Schneider: Well, I think the Ukraine case is a pretty straightforward run about all the work that they ended up doing more on the defense side.

Ben Buchanan: I would draw a distinction because those companies are in the defensive cybersecurity business. But, I would love to know more about a company like Tencent, which is on the 1260H list, basically identified as working with aiding the Chinese military. ChinaTalk readers will be well served by a deep dive into those kinds of companies and what they’re doing for the state over there.

Jordan Schneider: Reflecting back, I think it’s fair to say that the story of export controls was that it took a lot of political appointee expertise to come in and be the subject matter experts. We’ve had a lot of shows, and there have been a lot of papers written about how to build in more of a long-term analytical body to serve both Congress as well as the executive branch to get in front of this stuff. You don’t necessarily need CSET to exist to pay people to do it for you. What are your reflections on the ability for the government to grok emerging technologies? How would you structure this thing?

Ben Buchanan: It’s nascent, and it got better during the four years I was there. I am worried it is getting worse, and I’m worried we’ve bled a lot of talent from the intelligence community, and some of the people who I thought were the sharpest at understanding this technology are no longer there.

The analogy that I often drew upon was if you think about the early days of the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union were each starting to push into space and spy satellites and all of that. We built entire agencies essentially out of whole cloth to do that analysis and build those capabilities. Getting our own intelligence capabilities up there and then understanding what the Soviets were doing, that was a totally new thing, and I think we basically have to do something like that here. Now I’m not saying it’s a new agency, but I do think it’s that magnitude of community-wide change to respond to just a completely different technical game than the IC is used to playing or historically has been used to playing. And I think we were lucky to work with a fair number of folks in the IC who, at leadership levels, got this. David Cohen at the CIA is one example. Avril Haines and Charles Luftig at ODNI are others. There were people who got it. It’s just a question of time and consistent leadership. The President signed a National Security Memorandum in October 2024 that provided a lot of top cover and direction. And then we were all out by January. I don’t know what the status is now, but a big change is required at the magnitude of what we did during the Cold War to extend the reach of intelligence to space.

Jordan Schneider: It’s tricky though, because even the space analogy, that’s a discrete technology. Then, it was like, someone’s going to have to build the satellites, and then we’re going to give the photos to the people who know something about Russian missiles and figure it out. But the sort of technological overhang that AI is presenting is that you have this tactical and operational stuff around our conversation with cyber, but there’s a broader question of how do you set up an organization?

The number of job descriptions that are going to change and the ways that private sector companies are going to evolve in their workflows has the potential to be extremely dramatic. And there is very little in the sort of regulatory or bureaucratic structure that gives me a lot of confidence that just having a sort of body over there is going to do it, and that these organizations have enough capacity for internal renewal to really do the thing.

Ben Buchanan: I agree. The answer I gave you was the answer to how the intelligence community confronts the technology itself, which is different from the question of how they confront their own way of doing business.

You’re right that AI will and should change key parts of organizational structures, including in the intelligence community, in a way that space fundamentally did not. And it is fair to say we articulated that question and sent the very beginnings of gestures of an answer to that question. But first of all, the tech wasn’t there in ’23 and ’24 when we were really working on a lot of stuff. You can only skate to where the puck is going. But it is something that if we were in now, I would hope we were spending a lot of time on.

Jordan Schneider: I had this conversation with Jake Sullivan about experience, and asked him something like, “In what dimensions did you get better in this job in year four than you were in year one?” And on one hand, he was like, “I was burned out. I needed a six-month break somewhere in there.” But also he was like, “Look, if you’re in, living through crises, being in this, there’s just, there’s no way to simulate it.” Then I got to thinking, we’re not that far from a world where I can tell GPT-7 to build me a VR simulation of being Ben Buchanan in the summer of 2021 and try to send some emails and talk in some meetings to convince people to do FDPR on semiconductor manufacturing equipment. From a sort of future policymaker education perspective, beyond doing a PhD, think tank reading, writing, analyzing stuff, what other skills would you have wanted to have come in? And is there a world in which AI can help serve as that educational bridge to allow people to operate at a higher octane than they would be going in cold?

Ben Buchanan: The first half of that question is very easy. The second half is very hard. The first half of the question, essentially, is where did I get better over four years? Or what skills did I wish I had that I didn’t have in 2021? It’s just understanding how the process works, understanding how the U.S. government makes decisions, understanding how you call people, how you run meetings, how you put together an interagency coalition. I was very lucky that I got to learn from some of the best people on earth in doing that. Tarun Chhabra is the obvious archetype. That was a skill that I did not have going in, though I felt confident on the technology side. And when I left, I felt much more confident, like, “Okay, I’ve learned this.” How could you learn that on the front end? I don’t know if it’s an AI thing. I guess you could, you could maybe do it. But there probably is something in there about, you know, role-playing to me always felt kind of hokey, but like, how would you role-play this, and how do you get people to practice this skill and so forth? Maybe there’s something there. I hope there is, because it’d be great if our policymakers could hit the ground running on that skill in a way that I definitely did not. But I don’t know what it looks like.

Jordan Schneider: You’ve had a year or a little less. You’ve had coming up on a year now to just have more time playing around with models. What have you been using this stuff for? What’s different now that you have more bandwidth and more time to read?

Ben Buchanan: It feels longer than a year, Jordan. I can tell you that it hasn’t been the fastest year of my life. I have more time, but also more access to this stuff. It’s crazy that basically for the whole time I was in the White House, this stuff was not accessible on government computers, even on unclassified networks. Again, back to the challenge we were talking about. We tried to make it a little bit better, but this is a heavy lift. I just have much more time to use this stuff now, and I can, I can use this. When I write something, I love giving it to Claude and saying, “Look, you’re a really aggressive editor, tell me all the reasons this is wrong.” And I don’t take all of its edits. But I do find that if you tell Claude to be really aggressive, it’ll go after your sentence structure. It’ll say this is unclear. It’ll say, “Have you thought about this counterpoint?” I really enjoyed just having access to tools like that on a day-to-day basis. I don’t do as much coding and the like as I used to, but if I were doing software development, it really does seem like that has just changed everyone’s workflow. And there’s probably a broader technology lesson from that too.

Jordan Schneider: You’re writing this book about AI. What are the parts that feel easier to write? What are the parts that you’re still noodling on, which feel harder?

Ben Buchanan: Writing about AI as a whole is harder than I expected because of the very same thing that makes AI so interesting — everything is interconnected. You have a technology story that’s unfolded over a couple of decades, but really accelerated in the last decade. That’s an algorithm story, a data story, but it’s also its own computing story and the complexity of the compute supply chain. You have a backward-looking story, but then you also have the forward-looking story of how this is going to get better and recursive self-improvement, etc. You have the core tech, and then you have its application to a bunch of different areas. We talked about cyber. And then you have a bunch of geopolitical questions. The United States, China, national security, adoption, chip controls, all of that. And then you have a bunch of domestic questions. Are AI companies getting too powerful? Will we have new antitrust and concentration of power issues? What’s the trade-off between privacy and security in the age of AI? The jobs question, the disinformation question, so forth.

I love it because it’s this hyper-object where everything is so connected. If I’ve got this huge hand of cards here and they’re all connected, what is the way in which I unfold these cards on the page? That has been the challenge in teaching it in the classroom and in writing about it. And it’s incredibly frustrating, and anyone who tells you otherwise has not done it because there’s no easy way to do it. But it does give me even more appreciation for just the depth and breadth of this subject. This is also why AI policy is so hard — it doesn’t fit in jurisdictional boundaries. All the mechanisms we’ve set up to govern our processes break down when you have something this all-encompassing.

Jordan Schneider: You will have written four books in the time in which I will have written zero. A lot of what ChinaTalk does is kind of live at the frontier of that hyper-object, whether it’s AI or Chinese politics. But the bid to write something more mainstream for a trade press about this is different from your older books. What was the appeal to you of trying to bring a more kind of holistic thesis statement that can be read by more people than already listen to ChinaTalk about this topic?

Ben Buchanan: There are three reasons, and I don’t know the honest weighting of which one’s the most.

This subject is incredibly important. ChinaTalk is going to reach a lot of people. I’m not comparing audience sizes, but I do think a book-length deep dive treatment into this subject that’s accessible to a lot of people has value because it’s going to touch on many aspects of their lives and of policy. In a democracy, we all kind of have to engage with the most pressing issues.

There’s a lot of value in refining my own thinking by trying to get it on the page and structure it in a book. And I think in many cases again, you can live in the milieu and feel like you understand the milieu, but your own thinking just gets so much sharper when you’ve got to structure it across 300 pages and say, “What are all the really important things I’m going to leave out and how do I prioritize this and how do I unfold the different pieces?” So that’s been incredibly frustrating, but I hope it pays off, not just for the reader, but also for me.

I just get great joy out of explaining it or trying to explain it. Insofar as the promotions I got in the White House and the responsibilities I was given by the end being the White House Special Advisor for AI, I don’t think I got that because I had the deepest knowledge of AI in the world. You could take someone from Anthropic who could go much, much deeper into, “How do we do the reinforcement learning step of reasoning models?”

I think my comparative advantage was that I could understand it enough, and then I could explain it to people who don’t work in AI — the President, Jake, Bruce Reed — who have to manage the entire world, but who know this is important and want the crisp explanation. I’ve just gotten a lot of joy from doing that. That’s why I’m a professor, and why I was a professor before the White House.

Jordan Schneider: That’s very wholesome. But on that first point — when do ordinary people actually get a say in all of this? AI went from something only a handful of Bay Area and DC nerds cared about to something that now affects people’s 401ks and is starting to reshape workplaces. Returning to your earlier framework about what drives competition, the potential democratic backlash to the social and economic upheaval AI will cause feels like one of the biggest unknowns in the U.S.–China picture. To get the full benefits of this technology, we’re probably going to go through real social weirdness and real economic dislocation.

Ben Buchanan: It will be a political issue. And I think there’ll be a lot of dimensions of AI policy that show up in the 2028 presidential race. Jobs being one, data center infrastructure being another. Probably some national security dimensions to it as well. Child safety, another really important dimension, not my field, but one that I imagine is going to resonate in 2028. I think this is the case where you will see a lot of this show up in the political discussion. And I claim no ability to actually influence the political discussion, but insofar as I can help make it a little bit more informed by the technical facts, especially on the national security side, where I have a little more expertise, I think that’s a really important thing to do.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk a little bit about regulation. Social media came and went without any real kind of domestic regulatory action, and we’re dealing with the consequences of that. The shockwaves that will come if AI hits seem to be an order of magnitude or two larger than what we saw from Facebook and Twitter.

What are the tripwires where Ben Buchanan wants the government to step in and shape this technology? And on the flip side, what are the tripwires from a public demand perspective — what will it take for the public to insist on regulation?

Ben Buchanan: I think a core purpose of the government is to manage tail risks that affect everyone but maybe no one else has an incentive to address. In AI, that’s things like bioterrorism or cyber risks as the technology continues to get better.

We took steps on that using the Defense Production Act to get companies to turn over their safety test results. President Trump has since repealed those, but I stand by them as robustly good things to do with very low imposition on the companies. One CEO estimated that the total compliance time for our regulation was something like one employee-day per year. Pretty reasonable, but it also had tractable benefits.

Where I don’t think the government should be is in the business of prescribing speech — outside of a national security context — telling companies, “You have to have this political view,” or “You’ve got to have this take when asked this question.” That strikes me as a road we don’t want to go down based on the evidence I’ve seen so far.

We tried to be very clear. Even on the voluntary side, we focused on national security risks and safety risks. That strikes me as the right place to start, and I would be hesitant to go too much further beyond those core, tractable risks.

Jordan Schneider: There’s an interesting U.S.-China dynamic here regarding the AI companion context. That’s where I can see a really dark future where we’re all best friends and lovers with AIs that have enormous power over us. The Chinese system has shown its willingness to ban porn or restrict video games for kids to 30-minute windows. It’ll be interesting to see if we end up having a new version of a temperance movement, or some big public demand for government controls — or even a rejection of what’s on offer in the coming years.

Ben Buchanan: Look, that may happen. I’m not even sure we can debate how it would be good or bad. There is probably some context in which we could say, for example, “AI systems should not be helping teenagers commit suicide.” This is not a complicated thing morally. But there’s a different question — should the federal government be the one doing this, and what does that look like?

We didn’t really go near any of that. We focused on the national security risks where I think we can all agree — yes, it is a core federal responsibility to make sure AI systems don’t build bioweapons. Frankly, the government has expertise around bio that the companies don’t. The companies were the first ones who told us that — they wanted a lot of assistance, which is why we created things like the AI Safety Institute.

Jordan Schneider: Well, that was a punt. But there better be an AI companion chapter in your new book, Ben.

Ben Buchanan: I don’t have developed thoughts on AI companions, except that I absolutely have concerns about the way in which AI will erode fundamental pillars of the social contract and social relationships.

Jordan Schneider: I mean, right now we’re all walking around with AirPods, playing music or books.

Ben Buchanan: And podcasts — mine play ChinaTalk.

Jordan Schneider: Great. But it’s still me on the other side of that, right? I worry about the level of socialization we’re going to end up with when it’s just optimized. Whatever is in your AirPods is perfectly calibrated for scratching that itch, making every neuron in your brain fire. It’s a weird one. But you said you don’t have thoughts on this, so we can move on.

Ben Buchanan: No, I don’t have smart thoughts on it, but I appreciate the concerns about “AI slop.” Ultimately, I think the trusted AI companies will be the ones that are explicitly humanistic in their values. These are questions that aren’t for the U.S. government to answer, but for U.S. society to answer.

Jordan Schneider: Sure. All right, let’s close on AI parenting. I bought the Amazon Alexa Kids the other day. They had some promotion. It was like 20 bucks. And I was so disappointed. You figure it could talk to you in a normal way? It’s still really dumb. It’s kind of shocking that there are not “smart friends” for children yet.

Ben Buchanan: I think there’s a lesson there about AI adoption and diffusion within the economy. You have a few companies — Google, OpenAI, Anthropic — inventing frontier tech, but the actual application of that tech to products is still very nascent, jagged, and uneven. I don’t know what LLM is in the Amazon Alexa, but the general trend is that we are in the very early innings of applying this stuff, even as we’re racing through the movie to invent more powerful versions of it.

Jordan Schneider: Ben, I used to ask people for their favorite songs, but we keep getting copyright struck. So we are now generating customized Suno songs based on the interview. I’m going to do one about creating export controls, but I need you to give me the musical genre.

Ben Buchanan: The musical genre? It has to be jazz. Clearly, there is an element in which every policymaking process is improvisation. You have some sense of where you’re going, but I certainly didn’t feel like I was reading from a sheet of music — not that I can read sheet music anyway. But it has to be jazz, Jordan.

The notions of the past carrying momentum to the present.

Scaling is dead. Several people were already point that there are fundamentals in generative AI - which is mostly what falls under this “AI” umbrella - leading to this collapse. It’s funny as we are on the verge of the possible AI bubble burst, an interview that still defends AI scaling laws & “AI the most transformative since the railway”… beyond those facts, the interview seems to me a good future historical artifact, capturing some ways of thinking with concrete impact in geopolitics …