Bullshit Jobs in Chinese SOEs

"I jokingly called myself ... the 'chamber maid of the Party building office'"

Mia Zhong, who holds an MA in East Asian Studies from Stanford University and currently works in the tech industry, is our guest contributor today.

China’s State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) ecosystem primarily controls the country’s fundamental sectors, including energy, infrastructure, education, and telecommunication. A 2022 study estimated that there are more than 300,000 wholly state owned SOEs and around 1.5 million enterprises partially owned, counting all-in for roughly 68% of total capital of all Chinese firms in 2017.

Since Xi Jinping assumed power, the Party’s grip over SOEs has grown stronger. In his 2016 speech, he emphasized on “enhancing and refining the Party’s leadership over SOE.” In 2020, the central government issued a regulation that formally designate power to the Party committee over the board of directors in SOEs in “major business and management matters.”1

The following translation is a story originally published on Zhengmian Lianjie 正面连接, now deleted, which provides a rare personal account of work within an SOE and how the routines are heavily influenced by the Party building requests. The author Zhao Shuxin (赵书信) – likely an alias – is a young woman with a graduate degree and former employee in a provincial-level SOE. She started working on internal propaganda in the general affairs office in 2023 and extended her scope of work to external propaganda and other ideology-related areas.

It was a “stable, decent, easy job, an iron rice bowl,” that “gradually transformed from a spectator watching an absurd play, to an actress in the absurd play herself.” 从一个旁观荒诞剧的看客,逐渐成了荒诞剧的演员本身。In 2025, she resigned from the company and wrote a series of three articles recording her time there. The following translation is an excerpt of the second in the series, elaborating on her project to manage ideological risks on social media platforms.

Zhao’s response to the work is also characteristic of her generation: she called them “bullshit work.” The term was widely embraced by young workers after David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs was translated into Chinese in 2022, right when the working generation’s loathing for toxic work culture grew louder and fresh graduates were facing increasing unemployment.

“Ysxt” Work and My Power

It all began with what they called “online front ideological management work” (线上阵地意识形态管理工作). The so-called “online front” really just meant social media accounts. Ideological management meant monitoring the content of those accounts.

Put simply, on social media, any account that included our company’s name plus location within our province had to be managed, whether it was set up by employees or unknown individuals who simply registered in our company’s name. (for example, “N Province A Company Jiajia,” “Flower of C City A Company,” “N Province A Company F City Branch_908,” “XX Market North Gate A Company Service Hall,” or “Xihuayuan A Company Service Hall”)

Specifically, for accounts officially registered and operated by company departments, I had to monitor them in the following aspects: first, whether there was any content that were incompliant with set standards, such as content endangering national territory or sovereignty; second, to check for misuse of symbols like the Party flag, Party emblem, or Tiananmen. As for accounts created by unknown individuals in the name of our company, their mere existence was considered an ideological risk.

Interestingly, the term “ideology” sometimes turned out to be a risk and taboo itself. In all kinds of written expression, unless it was a formal institutional document, the Party-building department always referred to it as “ysxt work” (ysxt 工作).

“ysxt” are the first letters of the term ideology in Chinese Pinyin (意识形态, yi shi xing tai). Using the first letter in Pinyin is a popular rendering of certain terms online. The most used words are usually for fun and convenience, such as “xswl” (笑死我了, xiao si wo le), meaning “lol”, and “dbq” (对不起, dui bu qi), meaning “I’m sorry.” The method was later adopted to address terms that might trigger censorship for their political connotation, such as “zf” (政府, zheng fu), meaning the government, and “zzzq” (政治正确, zheng zhi zheng que), meaning political correctness. These renderings are borne out of speculation and self-censorship rather than concrete rules.

I remembered clearly how this task landed on my shoulders. One afternoon in November 2023, the Party-building department (党建工作部) suddenly demanded that a number of departments attend a meeting on “ysxt risk control across different fronts” (各个阵地ysxt风险把控). In the meeting room, the Party-building leader sat at the head of the table. Before my supervisor got a chance to talk, he spoke sternly: Internal or external, you must take serious actions against any ‘non-compliant’ new media activity. Set your rules! Clarify your measures! Swing the big stick first! As he spoke, he swung his hand forcefully through the air and clenched it into a fist.

That’s the Party-building department’s way of working. As the lead unit, they had the authority to break down their own tasks, pass them on to other departments, and act as the overall coordinator who regularly requested reports from these departments.

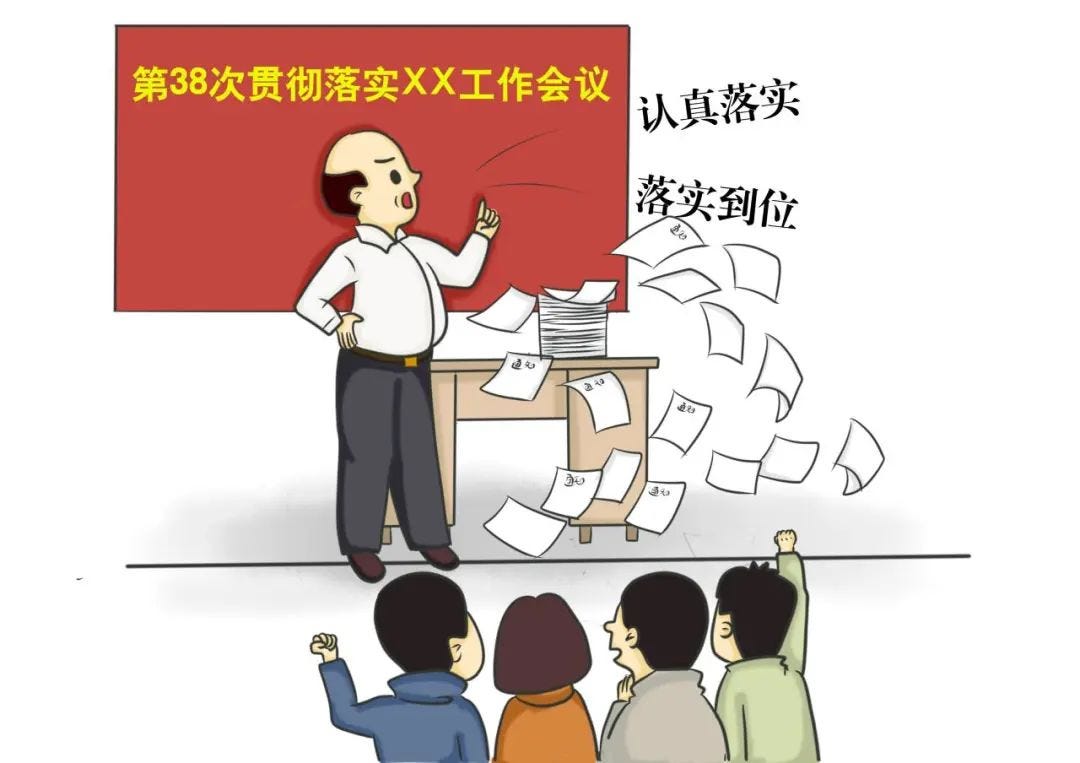

This way of working is an example of campaign-style mobilization 运动式治理. This type of governance breaks the formalized functional system and organizes resources and personnel to prioritize a designated task based on political purpose and mobilization. This mechanism can be observed on various campaigns and movements during the Mao era. More recent instances include mobilization control schemes during the Covid pandemic.

The social media management process went in three steps. The first was research, meaning manually searching across social media platforms to identify accounts whose names, profile pictures, or verification included our company name but were not official accounts.

The second step was rectification. We had to contact these unofficial “risky” accounts one by one through private messages, informing them that they could not use our company’s name, and requiring them to change their names or close their accounts within a set deadline. If there was no response, we had to report the account to the platform and request to close it.

If neither of these methods worked, then came the third step: recording the account in a “ledger” (台账) (what the government calls a spreadsheet) and placing it under “dynamic monitoring” (动态监管), which referred to checking the account regularly for new content posted.

Personally, I found this project utterly absurd. What right did we have to manage the social media accounts of people who had nothing to do with us? But because the task came from the Party-building department—and because Party-building evaluations and inspections could affect the company’s ratings, honors, and ultimately employee performance rating—there was no choice but to carry it out.

Upwardly, I had to report to the Party-building department and other inspection units. Downwardly, I had to lead different departments and branch offices to implement the task. My decisions would directly impact how much work each unit had to put in. Every time I asked them to submit materials, I always repeatedly expressed my apologies and gratitude.

In the first quarter of 2024, Miss Li from the D City branch company called me for advice. She wanted to know whether accounts whose owners she could neither identify nor contact still needed to be placed under dynamic monitoring.

I knew she wasn’t really asking for advice. It was more of a complaint. After all, we had already been working this way for half a year, and the rules were made clear. Out of guilt, I absorbed all her frustration and tried to appease her: I understand how everyone feels, but these are the work requirements. I’m watched closely by the Party-building office too. That wasn’t an exaggeration. In private, my self-deprecation was even sharper: I jokingly called myself an unofficial member of the Party-building office, their subordinate department, the “chamber maid of the Party building office” (党建部的丫鬟).

The departments in the provincial company were less implicit when showing their impatience. It was common for them to ignore my request for materials, and when I followed up, the person just replied with a cold snort: What can we do if they just don’t change their name or delete their account? Out of guilt and diffidence, I didn’t know how to respond when I first heard the question. But after repeatedly hitting a snag, I grew frustrated too and simply relied on the Party-building office: the Party-building rating would be deducted if issues were found, and your department manager would take you to speak directly with the head of the Party-building office. It's your choice.

Every time I compiled the spreadsheets of other departments and local branches, the hardest part was always aligning numbers. In theory, the total number of accounts in the current quarter should equal the newly added accounts plus the accounts carried over from the previous quarter. But in practice, it was common to have unmatched numbers. Sometimes there would be one or two more, sometimes one or two fewer. I knew no one would ever check the details of each account across the ledgers, so I just made up a couple accounts to smooth out the numbers.

However, the launch of the inspection and supervision work marked the end of my perfunctory work. The very same Miss Li who asked me for advice was flagged by the inspection team as an ideological risk: a non-official social media account using the company name was not included in the monitoring ledger. Our department received a “risk notice” issued by the Party-building office.

The email was sent to me and my supervisor, Miss Yuzhen, was cc’ed. At the end of the notice, it stated: “For repeated occurrences of similar problems, the Party-building office will request a meeting with the responsible person of the General Affairs Department; for issues of incomplete rectification during self-checks and self-inspections, and for repeated discovery of the same problems, the Party-building office will recommend the Party organization secretary to issue accountability measures” (对于屡次发现同类问题,党建工作部将提请对综合部相关负责人进行约谈;对于自查督查问题整改不彻底、问题屡查屡犯等情况,党建工作部将对党组织书记提出问责建议).

That threat infuriated Miss Yuzhen. She immediately called the Party-building office and sternly questioned: You said you wanted to summon my supervisor for a meeting—on what grounds? You talked about ‘repeated discovery of the same problems;’ why not ask yourself how much of the material for this work comes from us every year? This whole process of yours is nothing but formalism! She had once worked in that office, and the person who picked up the call was an old colleague of hers.

The meeting is considered a threat because it’s not a simple work meeting but a yue tan (约谈), an administrative pre-investigation meeting. It is used for information collection, warning, and investigation. Although the meeting itself doesn’t formally enforce regulatory or lawful actions, it is a strong sign of impending reprimand or actions, and therefore is taken very seriously. It started as a means of market regulation, land control, real estate control etc., and now already a procedure all state-owned institutions find handy.

Miss Yuzhen’s accusation of formalism was not referring to the artistic genre, but excessive procedural formalities (形式主义) in the context of the Party-state bureaucracy. The term refers to the idea of prioritizing formality over getting things done, and encompasses a broad range of behaviors. For example, initiating projects that might appear good on record but generate no actual benefit in reality, or designing an itinerary with performative work routines for the inspection team.

I never found out what the colleague replied, but as soon as she hung up, Miss Yuzhen dialed another number—this time, to Mr. Ren. He was now the VP of the Party-building office and was in charge of ideology work. The two of them had practically swapped positions. Her tone grew even sharper as she scolded him for being reckless: When you were in the General Affairs Department last year, did I ever send you a risk notice like this? And now, without even a word ahead of time, you start off by saying you’ll summon my supervisor? Is this really the right way to do work?

I knew that Miss Yuzhen was always tough when it came to drawing the line of responsibility—“clarifying the boundaries of one’s responsibility field” (厘清责任田) was something she often emphasized to me. But I had never seen her this furious.

Her anger, however, had no effect. The Party-building Department’s final response was: why could the inspection team find the problem, but the General Affairs Department could not? In the end, the matter turned inward and landed back on my shoulders.

Miss Yuzhen translated the inspection team’s message for me—they believed we didn’t put enough effort into this work. She guided me on how to implement the correction:

“Little Zhao, remember this: for this rectification of workflow, and every quarter from now on, you must send the work requirements by email. You need to make sure that every trace of work is fully documented. And in the third-quarter news bulletin, we must publicly criticize the branch offices tied to these accounts, so that they take it very, very seriously!”

In the Chinese workplace, especially conventional industries, it is a common way to address people who are younger and rank lower than you with “little” (小) plus their surname. For people who are older and/or rank higher than you, it’s common to add “big sister” (姐) and “big brother” (哥) after their name. I translated Yuzhen sister to Miss Yuzhen to avoid misinterpretation given how sister is used in the English context.

Miss Yuzhen kept one hand in her pocket, while her other hand shot forward, index finger jabbing the air. The words “very, very seriously” seemed to be squeezed out through gritted teeth.

I learnt from a few bloggers who write about workplaces to treat leaders as partners at work whenever possible, especially when facing other departments together. I complained: what exactly does it take for this work to be considered “done properly”? How could we possibly explain the platform’s search mechanisms? Even Disney allows people to register accounts with those three characters in their names—how could we stop others from registering accounts with our company’s name? Wasn’t the inspection team just demanding that we prove the impossible? Where would this kind of work ever end?

Miss Yuzhen waved her hand, giving the same reply I had once given to the branch offices: this is the way our work is done now—there’s no way around it.

I gave a bitter laugh and said nothing more. I opened the office software, ready to start drafting the rectification plan. Miss Yuzhen’s guidance was clear: when writing something for others, the most important thing was not to dig a hole for yourself—you had to write measures that could be carried out in practice. I wanted to ask Kimi to generate something for me but quickly realized I couldn’t even explain what I needed to a large language model. What kind of event was this, exactly? Could a LLM understand what “rigorous, but not digging a hole for yourself” (严谨而不给自己挖坑) looked like in practice?

The following week passed in endless rectification work. Rectification of the functional workflow naturally required the cooperation of everyone involved. To my surprise, at this point, Miss Li reached out to “discuss” with me again: couldn’t we simply exclude non-company accounts from our monitoring scope?

I had never expected her to bring up this question again right when her inadequate work had already caused me to have to rectify my work. Anger surged up inside me, and I shot back: on what basis?

She pulled out a regulation that had nothing to do with the matter. I finally dropped the patience I used to show low-level executors when I had the space to be generous. My voice turned sharp as I scolded her: why are you still asking me this? Haven’t we already made this clear? Even if you can’t identify who in the company opened the account, as long as it carries the company name and can be found through a search, it has to be monitored. After working on this for so long, how could you not know such a basic standard?

She faltered into silence. I couldn’t be bothered to say more and hung up with a “That’s it, then.” But the moment I tossed my phone onto the desk, regret set in. Just because I was being held to account, I passed on harsher demands to those below me. What else was that, if not the banality of evil? For so many moments in the past, I had been a nobody, forced to comply with rules that were inexplicable and meaningless, even suffering undeserved consequences. And now, I too had become a part of a small ecosystem of that very banality of evil.

An Endless Proliferation of Dirty Work

Shortly after, spreadsheets and data from different departments across the company were all submitted to me. I immediately set up three new folders on my computer: “Zero-Report Departments”(零报告部门), “Official Account Checks” (官方账号排查), and “Departments with Issues” (存在问题部门). Inside each folder, I created a ledger, and each ledger contained three sheets. Sheet 1 was named “Supervision, Self-Inspection, and Rectification Ledger”( 督查、自查及整改情况台账), which meant to reflect the process-oriented steps of rectification. Sheet 2 was called “Accounts Requiring Dynamic Monitoring” (需动态监测的账号) Sheet 3 was the dynamic monitoring ledger for each department, with check marks under each account by date to show it was being tracked.

After compiling the master sheet, the worst-case scenario happened. The latest spreadsheet showed 89 accounts in total, but when I added last quarter’s total to this quarter’s new accounts, the number was ten short. I didn’t want to believe it, so I reopened the spreadsheets from each unit, copied, pasted, and dragged down to sort. I tried twice, but the missing accounts still didn’t appear. Now resigned to my fate, I turned to Kimi to learn how to cross-check data in Excel on the fly, then began calling the departments whose numbers didn’t add up one by one.

One. Three. Five… By the ninth account, I got stuck again. It was already an hour past the end of the workday. Feeling overwhelmed, I pulled off my glasses, tossed them onto the desk, and slumped back in my chair with a groan. On the other end of the line, a colleague from Branch B—probably in her early thirties, usually the type to reply crisply with “I’ll handle it” or “I’ll ask around”—hesitated for once: If it really won’t add up… I still have two accounts on hand…

What kind of account is it? I straightened my back slightly.

The profile picture contains our logo, but the name doesn’t show it. The colleague from Company B replied.

I almost leapt out of my chair: Send it over, I’ll add it to last quarter’s existing accounts. Finally, that’s enough!

Seeing the numbers in the two spreadsheets finally match, I hung up the phone elatedly. I couldn’t help clenching both fists and drawing them through the air into my chest, like the final flourish of a symphony conductor.

But my celebration came too early. The next day, Miss Yuzhen came up with a new way to demonstrate our diligence: add columns for the creation date of each account and the date of its most recent post, to show the leadership that these accounts didn’t post for long, and are therefore “harmless” (无害) dead accounts.

This form of cengceng jiama(层层加码) is a typical phenomenon of policy implementation in China. Orders of policy implementation usually come top-down and in order to ensure the completion of goals and avoid punishment or failure, each layer in the system adds extra requirements or sets a higher goal for work when delegating to the lower level, eventually imbuing the grassroot level with unreasonable requests or unsustainable volumes of work. The most apparent example is the pandemic prevention during Covid, when local authorities added extra rules to prevent mobility regardless of one’s actual health status or risks of carrying the virus.

If her request hadn’t been specifically for this task, if it hadn’t been raised right before the end of Friday, if it hadn’t come after I had already finished consolidating everything, I might not have broken down. But at that moment, when I was full of hope thinking I could finally finish this dirty job, my supervisor taught me another lesson: the dirtiness of dirty work lies partly in its resilience—it always proliferates in unexpected places.

I only had enough control over my emotions to make a small “hmm” sound. The moment I sat back down, my throat felt blocked, and tears slid down my face. I didn’t want to make a sound. I randomly dabbed at my tears with tissues while notifying colleagues across the province to add the two extra columns.

A completely meaningless task got elevated to the level of ideology and was normalized, included in performance assessments and inspections, transformed into risk notices and supervision orders, and eventually turned into self-checks, audits, and spreadsheets. As long as I remained in this system, I would have to confront and solve the issues raised. Even if I didn’t want to solve them, I still needed to put in tremendous effort just to fully prove that “the responsibility isn’t mine” (责任不在我).

Because the functional departments of the provincial company did not directly bear responsibilities for production or business, they didn’t need to create new media accounts to promote operations. In practice, the bulk of investigation and correction fell on local branches. Every move I made turned into real additional workload for these grassroots units, endlessly pestering the branch secretaries who were already juggling multiple roles alongside this bullshit work.

Was it really that hard to stick only to the necessary work without adding excessive quota, and keep everyone’s lives easy? I was crushed by guilt, frustration, and helplessness all at once. The office was finally empty, and I couldn’t help but start crying out loud.

I Want to Change the System

By October, the rectification process was finally complete. In November, the Party Building Department planned to revise the company’s “Position Management Measures” 《阵地管理办法》, and Director Xiaoli reminded me that this was a prime opportunity to redefine responsibilities.

It was only then that I truly felt the reach of a “management department’s” power. If everyone in the company involved in this work had to follow my directives, the kind of work environment I could create for everyone became critically important.

I realized I had to stand up for my line and defend its boundaries. What I needed to do was straightforward in principle: prove that the General Affairs Department was “not responsible for unofficial new media accounts created in the past”. But in practice, it was far from easy. Our company’s principles meant that reasoning based on common sense alone wouldn’t suffice; that would be seen as avoiding responsibility or shirking difficulty. I had to both quote existing policies issued by our business line and identify loopholes in the Party Building Department’s rules and potential areas that could work against us.

I pulled all relevant documents, reviewed publications from the Party Building Department, consulted with the Group Office on how this work was assigned and executed at headquarters, and communicated with other provincial companies. I marked all my evidence carefully with a pen and sticky notes. Then I began drafting the materials for Miss Yuzhen to present at the meeting.

This was perhaps the most serious study of company policies I had undertaken since joining. And as I drafted the materials, I finally realized the most fundamental absurdity of this work: power had exceeded its boundaries. A company’s managerial authority only applies to its own employees—stretching one’s hand into someone else’s field, how could such work ever function? With that in mind, I drew the following conclusion in my first draft:

"According to the Group’s division of responsibilities, the General Affairs Department is responsible for managing official accounts created by various departments of the company based on business development and brand-building needs. For unofficial new media accounts whose creators are unclear, under the principle of clear accountability that ‘whoever manages is responsible, whoever uses is responsible, whoever approves supervises,’ the General Affairs Department has no approval or management authority over these accounts or their owners and bears no management responsibility. It is recommended that the Party Building Department coordinate with the Group to address these accounts."

Miss Yuzhen was generally satisfied with my materials but asked me to place the Group-level division of responsibilities at the very beginning. Since the Group Office did not handle the investigation and rectification of unofficial social media accounts, provincial companies should not be responsible for implementing Party Building Department’s related requests. The final report was therefore adjusted to two points:

1. The company’s Party Building Department should communicate with the Group’s Party Building Department to clarify the province’s ideological management responsibilities according to line management duties, implement these responsibilities, communicate management tools, and ensure consistency in line management duties.

2. According to the Group’s division of responsibilities, the General Affairs Department is responsible for filing and overseeing the province’s official accounts. For unofficial social media accounts with unclear creators, the General Affairs Department has no approval or management authority over these accounts or their owners and bears no management responsibility. It is recommended that the Party Building Department coordinate with the Group’s Party Building Department regarding these accounts.

There was nothing more I could do as an employee. I sent my leader into the meeting like a parent sending her child into an exam room. A few hours later, the moment Miss Yuzhen stepped into the office, she called out loudly: “Little Zhao, it’s settled with the Party Building Department!”

I instantly stood up and saw her fling a stack of meeting materials onto the table, announcing the result: from now on, this work would be assigned according to local responsibilities—if a municipal branch had problems, it would bear its own responsibility. The provincial company would no longer share joint responsibility for rectification.

Before Miss Yuzhen went into the meeting, I had expected that the outcome might not go entirely as I wished—but I never expected her news to diverge so completely from my intentions. I had hoped to clarify the responsibilities for the entire line and reduce the workload for municipal branches, yet the result became a way for me to shirk my own responsibilities. What faces would those who reported to me make upon seeing this new rule?

I could not accept that this work appeared as if I were “passing the buck” to subordinate units. The space atop had disappeared, and I had to start with what I could still manage to regain some control over the situation. At the end of the day, I still had decision-making power over how our line executed its work. I decided to revise the relevant internal management policies myself, removing the parts that were unfavorable to our management.

At first, I approached it by analyzing the various characteristics of the accounts. Besides the inclusion of our company’s name, another shared feature was that their follower counts were almost all in the single digits. Even if they posted content, the likelihood of anything going viral was extremely low. My proposal was conservative: “Accounts with fewer than 50 followers and no updates for over a year shall be considered low-risk zombie accounts and require no special supervision.”

But this idea was rejected during Director Xiaoli’s review: for the Party Building Department, leaving accounts unmanaged would create gaps in the work and inevitably invite criticism.

I accepted the director’s opinion and decided to return to the root of the problem: to keep authority within its proper boundaries. If an account, after verification, was found not to have been created by internal personnel, the General Affairs Department would have no management authority and bear no responsibility. This idea was eventually formalized in writing as follows:

Article 17 – Standardize the Social Media Account Investigation Mechanism. The General Affairs Department shall lead the investigation and cleanup of social media accounts. The scope of investigation primarily covers official company social media accounts and accounts created by employees related to the company. For unofficial social media accounts discovered during the investigation, if they were indeed created by company employees, the principle of local responsibility applies: whoever uses the account is responsible, and whoever manages it is responsible, and corrective actions shall be taken accordingly.

Article 18 – Strengthen Line Management of Social Media Accounts. The Marketing and Operations Department, as the department responsible for distribution operations, shall establish a management mechanism for the creation of social media accounts by distributors, ensuring full oversight down to the individual level and achieving closed-loop management.

The director approved this version, and I continued to report the revisions to Miss Yuzhen. Yingying was also called over to listen. Miss Yuzhen looked at me earnestly and asked, “Little Zhao, I just don’t understand—after all this time of rectification, why do these accounts keep popping up? Why do we need to tackle them all the time?”

This wasn’t the first time I encountered this question. Every time a new account appeared, Miss Yuzhen would ask in frustration: “I told them not to register, I told them not to register—so why are people still registering?!” At these moments, my mind would automatically recall concepts from my graduate exams: the emergence of new media, nodal behaviors… I never imagined that after leaving the exam hall, I would have to use these concepts to explain real problems. But academic explanations were meaningless here. Usually I just answered directly: Anyone can register now with just a phone number. Our name isn’t patented, so there’s nothing stopping them…

By now, I understood that what the leadership wanted was a more concrete answer. So I replied firmly: “Mainly the distributors.” Yingying added on the credibility of this claim: “Exactly—their business is a company consignment store, so it’s reasonable for them to do so.”

“Yes,” I said, “so last quarter we coordinated with marketing. They’ve already added this requirement into the distributor evaluations. If a distributor is found to have opened an account using the company’s name without authorization, they lose one point.”

The point deduction was the outcome of my discussions with colleagues in distribution management at the marketing department. When we negotiated possible measures, I only suggested vague terms of “serious handling”. My colleagues turned it into two concrete actions: first, provide relevant training for distributors; second, implement a point-deduction system. The evaluation scores determined how much funding each store would receive, which meant that opening an account would lead to a financial hit.

Of course, I knew that such strict control ran counter to the grassroots need of business development. But I ran out of energy to feel guilty. If blame was to be placed, it belonged to the Party-building office’s assignment itself. I was simply relieved to have finally found a genuinely effective way to prevent the endless appearance of new accounts, so my colleagues and I could get less entangled with this dirty work.

Miss Yuzhen said, “Now we need to be clear on one crucial point, making sure that no new accounts are opened by our own employees. If they do, we will call them out in a public notice.”

The problem had circled back to the starting point. The real difficulty was that I could never interfere with or control how any individual chose to use their personal social media accounts. I gave up any euphemism and said flatly: “That can’t be guaranteed, Leader.”

Miss Yuzhen was dissatisfied: “That won’t do.” The three words flew out of her mouth quickly. “Why? Distribution accounts are handed over to marketing, municipal accounts are handled under the principle of local responsibility, so the only ones left are the provincial company’s employees. We’ve made it clear that they’re not allowed to register accounts in their official capacity. If they knowingly break the rule, doesn’t that mean our negligence?”

I began explaining to her: in theory, social media accounts containing our company’s name could have been created by anyone living in this region or country. “Our authority only extends to company employees, not to people in society at large. If an account wasn’t registered by our employees, then it’s not our responsibility. So can’t we just leave it alone?”

“I see what you’re thinking now,” Miss Yuzhen said. “Because the Party building office pushed the responsibility onto us, you want to use this logic to remove the responsibility of municipal branches, is that right?” She still ignored common sense and returned to the framework she knew best—responsibility allocation—and directly pointed out my intention.

“Yes.” I knew the reporting was successful. As expected, she followed with: “All right, then we’ll report it to the leaders this way. You’ll come with me, Little Zhao.”

“What?” That was a surprise. I had never attended a special meeting with the leadership before. I made a joking comment about being afraid. Miss Yuzhen laughed: “Don’t be afraid. You think this is the right way to do it, so we’ll go and report it to them. Right now, the company’s leaders are still very tense about this matter. As long as we are right, it doesn’t matter even if we get scolded. We’ll just say it again and again—eventually, things will change.”

For the first time, I felt a solemn respect for Zhou Yuzhen.

More than ten days passed between drafting of the policy and its final approval at the leadership meeting. During this time, Miss Yuzhen once asked me to remove the phrase “if indeed created by company employees.” I did so. I guessed she felt that the line carried an undertone of shifting blames, which could irritate the leadership.

But right before we submitted the meeting materials, I hesitated and brought it up with her again: “Miss Yuzhen, can we keep that sentence?” I still wanted to make the boundaries of our work clear, so that colleagues in the line would not waste effort on meaningless tasks. By then, there was no one else in the office. Miss Yuzhen looked at me, weighed it for a moment, and agreed with a sigh. She figured that the leaders might not even notice that sentence.

I felt a wave of relief. Happily, I added the sentence back in. I clicked “send” on the meeting materials, then shut down my computer, stuffed my charger, glasses, and other belongings into my backpack before walking briskly out of the office building. I was filled with a sense of satisfaction: I had utilized my authority with conscience, and I had done everything within my power to create as much space as possible for the subordinate units that would have to carry out the work.

The next day I attended the meeting. though I only sat in the back row to listen to Miss Yuzhen report, I still put on my polyester work uniform and sat up straight. A few days later, however, an argument between Miss Yuzhen and a colleague from the Inspection Office plunged me into self-doubt again.

The matter itself was simple. To make one of their tasks “look good,” the colleague from the inspection office asked our department to produce a related ledger. Miss Yuzhen flew into a rage; the dispute finally ended with both sides conceding a little. Afterwards, as her anger subsided, she muttered—perhaps to comfort herself or the other colleague—that Little Zhou (the colleague from the inspection office) was a conscientious person and that he was only doing it for the work.

I had originally watched the scene for fun, but I was unexpectedly struck by the phrase “for the work.” My mind went back to the policies I drafted.

I was a conscientious person too. I was also pressured by certain people, certain systems, and certain powers, and resolved to solve this problem. But which was better: a lump of chaotic shit, or a lump of carefully thoroughly analyzed and organized shit? Had I really done something good for everyone, or was what I was proud of actually an unwitting aid to something evil? Did I leave a legacy or calamity?

“in six areas—including the implementation of decisions and plans of the Party Central Committee, the fulfillment of national development strategies, and the enterprise’s development strategy—must first be studied and discussed by the Party Committee (or Party Leadership Group) before being decided upon by the Board of Directors or the management.”

Interesting insights into the low-level working experience within the SOE structure!

Feels like from the comments Mia read Zhou Xueguang’s book on the organization of China’s Governance hahaha

Very confused by this article...

First, I think that this task she is doing is useful and reasonable. Even in the US it makes sense that Frito Lay would not want "Doritos Philidelphia" posting "Trump/Kamala is evil". Nor would they want random people making random Doritos instagram accounts.

Then it seems reasonable that to manage this risk, Frito Lay would have a social media manager who communicates with regional social media managers to make sure that these accounts don't get created or get reported if they are created.

THEN it seems reasonable that the social media managers at every level should keep a robust spreadsheet that allows them to track their work. The complaint about the added columns was bizarre to me because I would have just assumed that those columns would have been added in the first place. It also makes perfect sense that the managers at each level should be accountable for their work, that the work should be audited, that discrepancies should be explained, etc.

This reads like a complaint about having to do work. Am I missing something?