CCP Wartime Decisionmaking

Why leaders undermine their own foreign policy

Why do leaders with vast expert bureaucracies at their fingertips make devastating foreign policy decisions? Tyler Jost, professor at Brown, joins ChinaTalk to discuss his first book, Bureaucracies at War, a fascinating analysis of miscalculation in international conflicts.

As we travel from Mao’s role in border conflicts, to Deng’s blunder in Vietnam, to LBJ’s own Vietnam error, a tragic pattern emerges — leaders gradually isolating themselves from their own information gathering systems with catastrophic consequences.

Today our conversation covers…

How Mao’s early success undermined his long-term decision-making,

The role of succession pressures in both Deng’s and LBJ’s actions in Vietnam,

The bureaucratic mechanisms that lead to echo chambers, and how China’s siloed institutions affect Xi’s governance,

The lingering question of succession in China,

What we can learn from the institutional failures behind Vietnam and Iraq.

Listen now on your favorite podcast app.

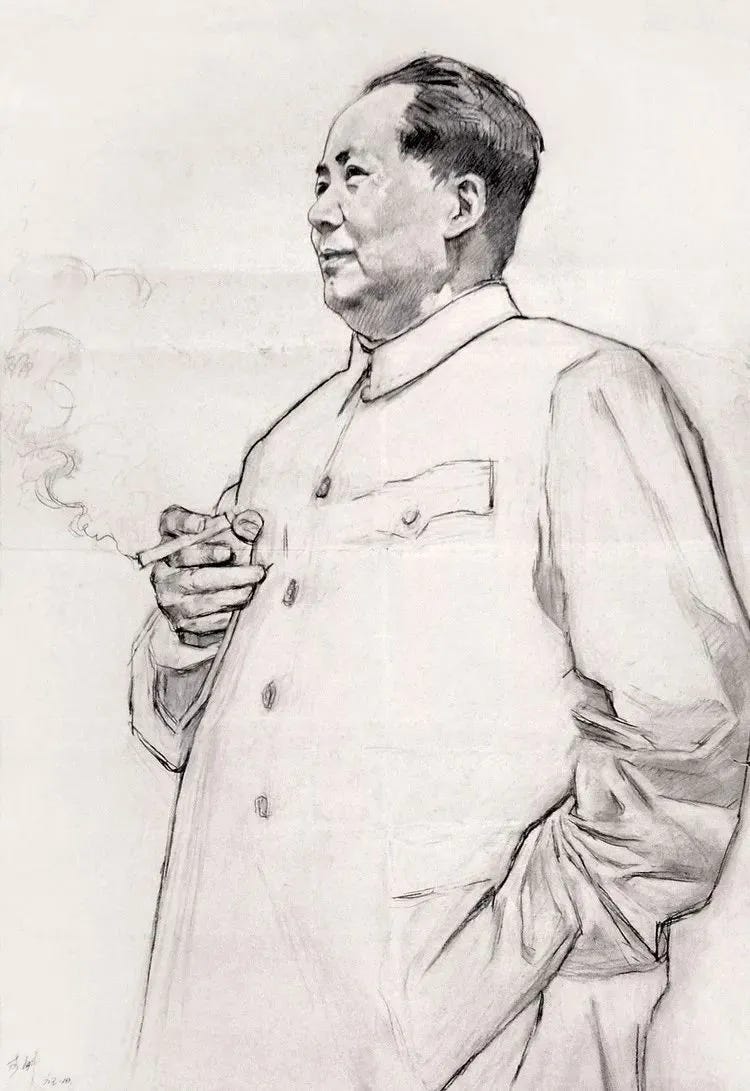

Mao, Hitler, and “Hot Hand” Leadership

Jordan Schneider: Let’s kick it off with Mao Zedong. You start the clock after independence. I’m curious, when you think about leaders like Mao who followed their instincts to achieve a remarkable place in world history — Mao bet on himself again and again and won. When Stalin pressured him to make a deal with the Nationalists, Mao said, “No, we’re going to fight and we’re going to win in the end.” Then the Japanese invaded and shifted the balance of power, and in the end, history worked in Mao’s favor.

Most leaders experience a series of successes and luck over the decades it takes them to reach power, which can build psychological confidence in their own instincts. As we think about the interaction between bureaucracies and leaders — when leaders trust their gut over other advice — how does that confidence in their instincts shape their later decision-making? When their instincts conflict with expert advice, do they trust themselves over the system?

Tyler Jost: That’s a great question. You could probably break it down into three categories of explanation.

First, some psychologists think human beings are hardwired to be overconfident. There’s a baseline tendency across the human population that when presented with gambles, people make riskier choices than they probably should, given a dispassionate look at the data.

Second, there’s a category which I think Mao probably fits into — certain personalities tend to be more risk-accepting than others. This could be because some people are comfortable with risks and taking gambles. It could also be because the way we perceive risk can vary among people. Some people might perceive the gamble of war as less risky than others. Mao probably falls into that category.

The third category has to do with the political phenomenon you’re talking about. In foreign policy decision-making, we often study the decisions of presidents, prime ministers, and dictators — leaders who have climbed up the political ladder. They’re already in office. That could trigger a “hot hands” phenomenon — “Look, I was able to get here, this must mean my views are good, and as such, I should trust those instincts as opposed to the data around me.”

Jordan Schneider: I’ve been going back to Ian Kershaw’s histories of Hitler. There are just so many calls in the 1930s where Hitler’s gut was right and the Allies folded. Invading Poland kind of worked out, and invading France went better than anyone could have imagined. There was a point when Hitler’s generals were about to kill him because they thought the calls he made in the late 1930s were too risky.

Then he made some epochal blunders — declaring war on the US, invading the Soviet Union — it’s understandable that someone who went from jail for a failed coup to nearly dominating Europe 20 years later could become overconfident and make terrible calls.

Tyler Jost: This is a book about miscalculation. Both historians and political scientists often try to evaluate individual decisions based on outcomes — if things turned out well, it must not have been a miscalculation, whereas if things didn’t, it must have been. That’s actually a problematic approach to history.

You can make a decision that ends up working out even though it was based on horribly inaccurate views of the world, and vice versa. If we really want to study the quality of decision-making, we have to start with temporal analysis. We have to look over time rather than examining any single decision.

If you had a 5% chance of things going your way according to the data, then that’s still a 5% chance. But if you keep making that bet over and over again, eventually it will catch up with you. For methodology— and this applies equally when doing historical analysis — you want to take a bird’s-eye view. What is the pattern of success and failure over time as opposed to specific instances in isolation? The book tries to go deep in particular cases to illustrate the mechanisms, but it’s important to start with base rates.

When Mao Stopped Listening to Bureaucrats

Jordan Schneider: You can tell a story of the 1930s where the international world is weak and ripe for toppling, but suddenly the most Jewry-Bolshevik infested one happens to be the one still fighting even after losing millions of people in the summer and fall of 1940. You can draw terrible extrapolations based on a limited set of data points.

Let’s return to Mao. From an epistemological perspective, you have a ton of material from the Nianpu 年谱 of what the daily leaders are discussing and the documentation of their decision-making. Were you surprised that all of this was out there for you to sink your teeth into once you started investigating?

Tyler Jost: The Chronicle of Mao Zedong or Mao Zedong Nianpu 毛泽东年谱 was released just before I started graduate school. I don’t think I realized then how lucky I was in my timing. The party archives publishes compendia of daily activities of senior revolutionary-era leaders, such as Mao’s meetings with his advisors and Mao’s meetings with the Politburo. Not just the ones that were released or publicized in The People’s Daily 人民日报, but the private ones as well, where the real action happened.

I stumbled into this, knowing I was interested in writing a dissertation about decision-making. It so happened that the most detailed records pertaining to Mao’s decision-making had just been released by the party.

Jordan Schneider: Give us an overview. You periodize Mao’s administration from 1949 to 1962 and from 1963 to 1976. Let’s start in that early era. What was the national security decision-making apparatus that he was working around?

Tyler Jost: Through all of these frameworks, start with the leader. I’m interested in miscalculations about questions of war and peace. The assumption at the starting point — this is a theoretical assumption you could question, but I try to show empirically that it’s sound — is that you have to get the leader on board. Leaders make the final call on big decisions in foreign policy. There could be other subsidiary decisions that low-level bureaucrats get to make on their own, but the starting point for any analysis has to be the leader.

This is an easy assumption that aligns with the historical understanding of Mao’s era. Mao was a dominant force in decision-making. The reason I say that the period between 1949 and 1962 was different from roughly 1963 to the end of Mao’s life is that the system Mao created when they founded the government in 1949 was, comparatively speaking, quite integrated.

What do I mean by integrated? There were many mechanisms by which the leader was able to reach down into the Chinese party-state and extract information needed to make decisions. There was an unusually high status of the Foreign Ministry, which was a function of the fact that many individuals who went into the Foreign Ministry early on had been part of the military and had revolutionary credentials. This included Zhou Enlai 周恩来, who was the first foreign minister and concomitantly the Premier 总理 of the country at the outset. His replacement, Chen Yi 陈毅, was similar — one of the Ten Marshals 元帅/大将.

So that’s a diplomatic core or critical mass of diplomatic information that Mao had access to. Then obviously there’s the military. The military already had a high standing and good access to get information up to Mao. From the late 1940s to the early 1960s, Chinese leaders’ ability to get the information they needed from the state system was pretty good.

Jordan Schneider: Okay, let’s take it to 1962. What was happening between the mainland and Taiwan?

Tyler Jost: 1962 is four years into the Great Leap Forward. The Chinese economy is doing incredibly poorly. There’s a suspicion that perhaps the regime is not fully stable. In the spring of 1962, Chiang Kai-shek, who had been monitoring the situation on the mainland very closely, got it in his head that this was his last favorable opportunity to take serious military action (“Project National Glory/國光計劃”) against the mainland to foment a revolt that would ultimately topple the communist regime.

He takes a series of actions, from writing in his diary about how serious he is about military action against the mainland to setting up internal Taiwan military bodies, convening military planning meetings, and reaching out to the Americans to see whether they would support something.

Unfortunately for Taiwan — and this is eventually what’s discovered by Mao — this is a year after the Bay of Pigs in the Kennedy administration. The US and Taipei had signed the Mutual Defense Pact a couple of years prior, which essentially gave veto authority to the US for any major military operations, including the one Chiang had in mind in 1962. Chiang essentially has to decide whether he’s going to go it alone, go back on the treaty commitment, or just back off. That’s the scene setter before we get to the mainland side of things.

Jordan Schneider: What did Mao know? When did he know it, and what was the decision space he was facing once he started hearing whispers of Chiang restarting the civil war?

Tyler Jost: Mao gets a pretty early wind that something serious is happening in the spring of 1962 through intelligence channels. He immediately engages with the bureaucratic establishment. There’s a series of Politburo, Central Military Commission, and Leading Small Group 领导小组 meetings, all of which are activated to determine what China should do.

What’s remarkable about this — because this is 1962, four years into the Great Leap Forward — is that the Foreign Ministry is at the table, military officers are at the table, and there’s pretty candid discussion, particularly given that Mao early on in the crisis seems to indicate he’s taking the chance of an invasion seriously.

Beijing eventually lands on a two-pronged strategy. One in which the PLA is going to mobilize, but do so publicly to showcase that it’s aware of what’s happening and prepared to defend itself militarily. But then critically — and this is where the Foreign Ministry and Zhou Enlai play a big role — they activate a diplomatic channel that the PRC has with the US.

Remember, this is the Cold War, so there’s no formal diplomatic recognition between the two countries, but there is an ambassador-level channel in Warsaw through which the two sides can communicate. The Foreign Ministry officials, including Foreign Minister Chen Yi, have this intuition that Chiang Kai-shek is probably going rogue, and it’s unlikely the US is behind it. If the US isn’t behind it, they’ll likely be able to rein Taipei in.

That’s exactly what they do. They reached out to the US in Warsaw in the summer of 1962, and received a message loud and clear that was personally approved by Kennedy. It’s fascinating — I trace that message from Kennedy to the US ambassador in Poland to Wang Bingnan 王炳南, the representative from the PRC side. We have both the US cable and now the Chinese cable. We know the distribution list for the cable on the Chinese side. It goes not just to Mao Zedong, but to all the senior Politburo members, members of the Diàochábù 调查部 (the domestic and foreign intelligence agency at the time), Foreign Ministry, CMC, and so forth.

Wang says in his memoir — and I think this is proven by Mao’s subsequent actions — that the information coming through the Foreign Ministry channel had a big impact on Mao’s thinking. You can imagine it breaking very differently. Think about the First Taiwan Strait Crisis or the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis — Mao had previously used violence to achieve his military goals. He doesn’t in ‘62 — he’s more circumspect, in part based upon the information the Foreign Ministry was able to gather for him.

Jordan Schneider: There were other times in the 50s where he saw the upside of escalating — in the Korean War and then in the Taiwan Straits, where he seemed to think, “We need to make sure our revolutionary fervor is still high.” It’s interesting that the Great Leap Forward, as you argue, has him calibrate down how aggressive he’s willing to be in running risks. So Mao, good job, you avoided World War III in 1962, but seven years later you’re back at it again. What was he thinking in the China-Soviet border disputes in ’69 that almost brought us to global thermonuclear war?

Tyler Jost: It’s probably an exaggeration to say either of those would have resulted in a world war. Things certainly were worse in ’69 compared to ’62.

Again, it’s important to provide some context. By 1969, the Sino-Soviet Split 中苏交恶 was well underway, and the two sides were increasingly confrontational, both vying for leadership in Africa and Southeast Asia, and also along their shared border. They had unresolved territorial disputes dating back to the founding of the PRC. A series of skirmishes, particularly on the northeastern part of China’s border, began to escalate in the late 1960s.

Alongside this is the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia under the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine in 1968. The combination creates real anxiety in Beijing about what might happen. Mao gets it in his head that some sort of Soviet military action needs to be countered, and the right strategy is through a clear demonstration of military force — hit first, demonstrate resolve, and the Soviets to back off.

Mao was wrong on two fronts. First, the Soviets would not back off. Second, he misjudged the severity with which the Soviets were contemplating military action prior to China initiating conflict in March of ’69.

From the behavioral indicators of the Soviet Union — what does the Soviet Union do in response to the ambush in March of ‘69? They escalate, both locally in the northeastern part of the border and by August, opening another front in the western part of China’s territory. By fall 1969, the Soviet Union was making veiled nuclear threats. How serious those threats actually were is debated quite fiercely among historians. But China took the threats seriously.

Based upon the Soviet records we have prior to March 1969, there’s no indication that military action was in the offing. In other words, Mao creates the type of military escalation he fears through his own actions. From that perspective, I argue that the Sino-Soviet border conflict in 1969 was a miscalculation on Mao’s part.

There are many ways of trying to rescue rationality or good judgment from disaster. There are potential ways to say, “Well, maybe Mao was after this or that,” and in the book, I try to address each one. But the argument the book makes about why this miscalculation occurs has to do with how institutions linking the leader to the bureaucracy had changed.

Unlike ’62, the lead-up to and then the Cultural Revolution 文化大革命 itself had decimated the connective tissue between Mao and the foreign policy bureaucracy. This begins around 1962 as Mao starts contemplating his own death. The quote nominally ascribed to him is “What will happen after I die?” Mao increasingly feared that what he observed during the Great Leap Forward was a premonition of the lack of revolutionary zeal that would overtake the Party after he was gone. In that regard, he was absolutely right.

How do you prepare for that? You need to begin attacking key leaders within the bureaucratic establishment who you perceive to be not revolutionary enough. This happened as early as fall 1962 and continued. The way Mao made decisions in ’63, ’64, ’65 shifted. The forums he used became more insular and exclusionary. All of this built up to the atomic bomb that Mao unleashed upon the foreign policy bureaucracy in the Cultural Revolution.

Jordan Schneider: Is it fair to consider ideology versus cold calculation as a variable? In 1962, he was burned by a dumb series of ideologically driven decisions that starved tens of millions of people, and he was reconsidering. By 1969, he was at a very different point, and he was seeing ghosts — both in the Party and around the world — which led him to read the Soviet Union poorly.

Tyler Jost: There are several ways to think about ideology. I want to emphasize that it’s important as a driving force in foreign policy decision-making, not just in China but in other countries as well.

One way to think about ideology is as a baseline set of left and right limits about what is permissible to political debate.

In Beijing, the Cultural Revolution narrowed the range of politically permissible opinions one could potentially have. This is bound up in how the institutions I discuss in my book are expressed. These institutions are the rules governing how a leader and a bureaucrat are supposed to interact. There’s a literal sense in which those rules can shape information flows between actors.

If I eliminate the Politburo, that removes a mechanism by which information flows upward to the leader. The transaction costs associated with getting information to the leader might be higher, but there’s also a strategic element to how bureaucratic actors respond to rule changes.

The rupture of connective tissues between leaders and bureaucrats — fragmenting the system — signals to bureaucrats about the political and ideological environment. In environments where this connective tissue has been stripped away, bureaucrats become more cautious in their reporting.

They end up spending energy not on determining the true state of the world, but rather on figuring out what they think the boss believes.

In that type of environment where information flow between leaders and bureaucracies is poor, bureaucrats focus on three questions: “How can I find out what the boss thinks? How can I find information that confirms that prior belief? And if I can’t do either of those things, how can I make my report so vanilla that no matter what the leader actually thinks or what actually happens, I remain safe?”

The result is either ideologically charged information designed to confirm what the leader has deemed ideologically correct, or reports so stripped of meaningful content and filled with ideological dogma that they’re no longer useful to the leader.

Jordan Schneider: This reminds me of Hitler. There was someone who walked around with what they called a “Führer machine” with big fonts because Hitler’s eyesight had deteriorated by the time the war started. Whenever they saw Hitler feeling down, they would print out an article saying how awesome and amazing he was and how everything was great. When you reach the point where you need psychological boosters of feeding leaders information that makes them feel good, you’re probably not in the best state for good, hard-nosed national security, analytical decision-making.

Tyler Jost: Indeed. One argument I encountered early in this project was that once leaders destroy this connective tissue, they know they’ve done so. They know their subordinates, being rational and strategic players, have incentives to provide biased information. Shouldn’t a rational leader then discount everything supplied to them?

In that fragmented institutional arrangement, it might seem to revert to a single leader making decisions independently, without necessarily making the situation worse. The argument I make in the book is that while this might theoretically be true, if we accept that human beings are prone to bias and enjoy hearing good news about themselves without properly discounting information that confirms their priors, then this situation can lead to an echo chamber.

Jordan Schneider: Another interesting dynamic you explore is fears of a coup. This was obviously relevant in Hitler’s case and very relevant for Mao as well. They began to wonder, “Are my generals going to shoot me and throw me overboard?” With Mao, Stalin’s case hung over him as the disaster he wanted to avoid — losing revolutionary edge and having the founder of the nation thrown under the bus.

Tyler Jost: Precisely. The book argues that these institutions don’t arise deus ex machina — they don’t appear out of nothing. They’re political choices informed by leaders’ calculations about how much threat the bureaucracy poses to their political survival and agenda, and how much they need that bureaucracy to accomplish their goals while in office.

The most troubling combination, exemplified by the Cultural Revolution, occurs when leaders perceive the bureaucracy as threatening.

In Mao’s case, he was concerned about what the bureaucracy would do after he was gone and felt the need to rekindle revolutionary fervor in the party. The worst scenario is when leaders both fear the bureaucracy and are inwardly focused on domestic rather than international policy.

You can imagine a different world where you fear the bureaucracy but face a threatening international environment and have ambitious international goals. In that case, you would need to balance your fear with the demand for information that only the bureaucracy can provide. The worst combination occurs when you fear the bureaucracy, but you’re inwardly focused and have no need for their expertise. In that situation, why assume any risk? You simply cut them out.

The Other Vietnam War

Jordan Schneider: Let’s fast forward to Deng Xiaoping in 1979. What was Deng thinking in ’79 when he ended up invading Vietnam?

Tyler Jost: The 1979 case is a forgotten war, but it shouldn’t be because it’s really consequential, both in terms of the geopolitics of the Asia Pacific region for the last stretch of the Cold War and what it tells us about decision-making in China and its potential pathologies.

China decided to launch a punitive war against its southern neighbor, Vietnam, in 1979. The logic that Deng consistently articulated both internally and externally was that China needed to punish Vietnam for its invasion of Cambodia and its growing relationship with the Soviet Union through a demonstration of battlefield strength.

The PRC planned to invade for a short period of time to display the power of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). They frequently used the phrase that they were going to “teach a lesson” to their southern neighbors. The analogy at the forefront of decision-makers’ minds, particularly Deng’s, was the 1962 war with India, where this strategy worked reasonably well.

In 1962, the Indians underestimated Chinese military capabilities. The battlefield demonstration that fall showed that the PLA was a force to be reckoned with. They had the upper hand at the border, and India revised its policies accordingly.

That success wasn’t replicated in 1979. To be fair to Deng Xiaoping, China did eventually achieve its tactical military objectives. However, the strategic motive — the real reason why China invaded in the first place — was not met. There are these quotes from newly available Vietnamese archival evidence where they state, “It was not China who taught us a lesson; it was we who taught them a lesson.”

Even though the PLA eventually reached its tactical objectives, the high casualty rate and slow advance demonstrated how severely the Cultural Revolution had damaged the PLA. The military prowess that the war was supposed to highlight in the eyes of Vietnamese decision-makers failed to materialize. From that perspective, the strategic calculation failed.

Jordan Schneider: What were the analytical errors that Deng made in this decision?

Tyler Jost: Part of it stems from misunderstanding the state of the PLA. Most evidence suggests that Deng eventually realized this prior to the invasion, around January. Ironically, most good information Deng received right before the invasion came through informal channels because people were afraid to speak candidly in more formal settings.

By that point, Deng had already committed himself to pushing this forward as part of his political agenda, making it difficult for him to back down by January.

There was another set of geopolitical and diplomatic errors: a lack of consideration for how Vietnam would respond if the PLA didn’t perform as well as it had in 1962, and a failure to assess what that would do to Vietnamese perceptions of PRC capabilities and resolve. That question was never asked. The debate around the war was very shallow.

In December 1978, the months prior to the war, they also misread the US. This is interesting because it’s sometimes suggested — partly as a political strategy Deng employed after the war failed to achieve many of its strategic objectives — that the war was a way of demonstrating China would be a good ally to the US. The narrative implies the US was secretly encouraging China to take this action, and Deng was taking one for the team to establish good credentials and secure normalization and healthy relations against the Soviet Union in the 1980s.

What we now know from US archives is that President Jimmy Carter actively discouraged the invasion. Deng Xiaoping took his famous trip to the US in January 1979, right before the invasion. Carter discouraged him both in small groups of advisors and in one-on-one meetings. Carter told Deng, “You have other options available to you. You could move your forces to the border and engage in a series of limited operations which might draw some Vietnamese forces north away from Cambodia without risking the international backlash this war will create.”

Jordan Schneider: The Vietnamese had defeated the Americans. Did the Chinese think the Vietnamese were unprepared? Regardless of the internal assessment of the PLA, the fact that Deng thought Vietnam wouldn’t be ready for a fight after spending 15 years battling the most advanced military in the world — and that they couldn’t stand up to China — is absurd.

Tyler Jost: It’s interesting. This dovetails with your first question about why people tend toward optimism in their assessments when they don’t examine data. This would be one potential data point supporting that first category of explanation.

Jordan Schneider: What do you think about Joseph Torigian’s argument that this was actually just a way for Deng to solidify power domestically? Hua Guofeng 华国锋 was leaving the scene, Deng was coming in, and almost everyone in the bureaucracy disliked the decision. But Deng said, “I’m going to show who’s boss. We’re going to do this anyway.” This was how he fully demonstrated to the system his control over the PLA — by forcing them into doing something they didn’t want to do, showing he was the new Mao.

Tyler Jost: There are two ways of thinking about this argument. Joseph’s book discusses it, but the most detailed articulation of this political motivation comes from Xiaoming Zhang’s excellent book Deng Xiaoping’s Long War.

The first interpretation, which Professor Zhang emphasizes, is that the PLA needed reform. Deng needed to demonstrate the military weakness of the PLA to drive organizational reforms within the military. The interesting thing is that the primary evidence for this logic comes from a speech given toward the end of the conflict.

There are two ways to read this. Deng was certainly aware of what he called “bloatedness” within the military in the 1970s. However, it’s very difficult to find anything in the historical record prior to the war where he states that the war would allow him to pursue this political agenda.

One interpretation of the fact that this document appears toward the end of the conflict is that perhaps he felt this way all along, which is certainly possible. We must be circumspect about asserting what leaders believed at certain points. But to me — and Joseph wrote this in his book as well — that speech reads quite defensive, as though Deng was trying to justify what he’d done. From that perspective, one could argue it was an ex post rationalization for what China gained from the war, rather than a belief Deng held throughout.

The second interpretation is as you articulated it — Deng knew the position would be unpopular, but pushing through an unpopular policy would demonstrate political strength, affirming his position vis-à-vis Hua Guofeng. That’s also possible.

The weakness in that argument is the intimate involvement Deng had in planning the war. If we accept that the war didn’t go as Beijing hoped and Deng was responsible for planning it, that’s an enormously risky move because he tied himself to the planning process. While possible, this explanation wouldn’t account for many other aspects of the overall decision-making process.

Jordan Schneider: More broadly, do you get more erratic decision-making when you have a leader who feels comfortable in power, or when they’re at the beginning or end of their reign, or when they perceive domestic threats?

Tyler Jost: Going back to our discussion about the Cultural Revolution, there’s an analogous argument here as well. The political contestation inside Beijing is important to the story I tell in my book.

Elite politics were quite contentious in the mid-to-late 1970s, making it beneficial to keep institutions fragmented.

The connective tissues ripped out from the Chinese system during the Cultural Revolution weren’t repaired. Most attempts to restore connections between leaders and the bureaucracy didn’t happen until after the Hua-Deng power struggle subsided in the 1980s.

Jordan Schneider: Fast-forwarding to 2025, much discussion revolves around whether Xi Jinping will stay in power. It’s important to internalize that China’s last major military action began right after a power transition. Xi will eventually die, leading to another power transition with volatility that might cause leaders to make terrible decisions. This insecurity appears in many of your case studies, causing people to narrow their information sources and make increasingly reckless decisions.

Tyler Jost: That’s exactly the right question to ask. While I don’t speculate about Xi Jinping and Taiwan, the succession problem and the institutional choices Xi must make to navigate those perilous waters deserve more attention. War could theoretically result from power balance shifts, perceived lack of American resolve, or miscalculations before that point. However, the succession problem remains the unnoticed elephant in the room that will become more obvious as time passes.

Jordan Schneider: Is there another case study of succession-driven decision-making?

Tyler Jost: Mao’s case is the primary succession example. You can view the 1969 conflict as rooted in institutional choices Mao needed to make to secure his legacy after his anticipated death in 1976.

The succession problem can also be viewed from the other side of the transition — whoever inherits power is likely in a politically precarious position because of the types of people that leaders, particularly personalist ones, bring into their inner circle toward the end of their tenure. These successors inherit foreign policy problems and dysfunctional institutions that make them prone to miscalculation. That’s what happened in the 1979 war.

Jordan Schneider: Toward the end of a leader’s tenure — whether democratically elected or autocratic — you argue, the quality of their advisors declines. Can you choose a case study to illustrate this?

Tyler Jost: One of the most fascinating aspects of foreign policy decision-making is how political selection institutions — what we typically describe as the difference between democracy and autocracy — both matter and don’t matter.

One benefit of democracy is that outgoing leaders don’t have to worry about what happens after they leave office and face constraints on how they can arrange the political landscape after their departure. In that sense, autocracy creates more opportunities for the pathological institutions my book discusses.

Nevertheless, democratically elected leaders can still fear what bureaucracies might do to them politically. Two cases examine this in depth. The first is the Indian side of the 1962 Sino-Indian border war and Nehru’s apprehensions about the foreign policy establishment, particularly the Defense Ministry and military and intelligence apparatus.

The second example occurred right here in the US — the reconfiguration of the National Security Council under Lyndon Johnson after he assumed office following JFK’s assassination in 1963.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss Vietnam. After JFK was assassinated, LBJ was suddenly in charge of JFK’s people, who hated his guts and were about to kick him off the ticket before JFK died. Take it from there, Tyler.

Tyler Jost: The argument in my book is that these dynamics you described — this unusual path to power in 1963, coupled with LBJ’s psychological predispositions — led Johnson to be tremendously paranoid that the bureaucracy threatened his political agenda. His primary focus was passing two hugely consequential pieces of domestic legislation pertaining to civil rights and the Great Society. We have him on record, both during and after his presidency, saying that these were his priorities.

Jordan Schneider: You quote him saying that Great Society legislation was “the one woman I truly loved.” As a serial adulterer, that statement carries weight coming from LBJ.

Tyler Jost: Earlier, we discussed the worst possible political environment for institutional efficiency and effectiveness. It’s a situation where you deeply fear the bureaucracy while focusing on domestic agenda items. The irony is that while Johnson inherited a reasonably well-functioning foreign policy decision-making apparatus, he intentionally took steps to undermine it.

Johnson established a very insular forum for his decision-making process known as the “Tuesday Luncheon,” which excluded a vast swath of the national security bureaucracy from important discussions. His reasoning was clear. In a retrospective interview quoted in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream, Johnson stated he knew the bureaucracy would punish him through information leaks that would make him look bad. He believed that when he held National Security Council meetings, information would “leak out like a sieve.” In contrast, these Tuesday luncheons never leaked anything.

Johnson’s logic for reorganizing the decision-making institutions was entirely political — a careful calculation he made. However, he paid a big cost for this approach. While making the most consequential choices of the second half of the Cold War for the US, he committed perhaps the biggest blunder in American Cold War history. It cost him politically in 1968, and he decided not to run for reelection because he knew he would lose.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s dive deeper into 1965. What information didn’t Johnson receive that might have led him to avoid escalation in Vietnam?

Tyler Jost: You can trace this back even further to the summer and fall of 1964. Several key individuals expressed deep apprehension about escalation in Vietnam — George Ball, Chester Cooper in the National Security Council, and others in the State Department’s intelligence apparatus (INR), like Allen Whiting.

All these individuals were systematically sidelined. There’s a myth that George Ball was given a voice in the spring of 1965, but in my book, I demonstrate that his influence was minimal compared to what he tried to communicate to Johnson earlier in the summer and fall of 1964.

As a result, all key decisions regarding escalation occurred in a very insular setting. LBJ was advised principally by McGeorge Bundy (National Security Advisor) and Robert McNamara (Secretary of Defense), with Dean Rusk present but clearly suffering from a degree of imposter syndrome. Johnson made the call for escalation based on a very narrow set of information and considerations, and the results speak for themselves.

The Making of Siloed Institutions

Jordan Schneider: Fast forward to 2016. Let’s discuss Trump’s national security decision-making in this context.

Tyler Jost: I should caveat this by saying that the study doesn’t consider the Trump administration’s decision-making institutions in any way, shape, or form, but it has a theoretical framework that we could apply. We can think about Trump’s position coming into office in 2017 and what happened within the decision-making structure.

Generally speaking, President Trump inherited a number of international problems in 2017, ranging from North Korea to Afghanistan to other parts of the Middle East. The demand for information and advice from political advisors or the national security establishment remained substantial. However, Trump came in with healthy skepticism and limited experience dealing with the foreign policy bureaucracy.

These two countervailing forces — the threatening aspect of his position and the demand for solutions to Afghanistan and North Korea — placed him in a middle ground that the book discusses.

I call it a “siloed institution” where you limit what any single bureaucracy can do independently while still depending on them.

It resembles a hub-and-spoke system with the leader at the center. Individual bureaucratic nodes gain access and relay information upward, but they don’t communicate effectively with one another or coordinate particularly well.

Some evidence suggests this might have occurred, at least at the margins. Journalistic accounts have revealed that lower-level components of the National Security Council system — which have existed for decades and serve as connective tissue at the deputies and sub-deputies levels for information sharing, policy coordination, and analysis — were perhaps less frequently utilized. This would be consistent with the arguments.

The outward-facing signaling or messaging strategy sometimes appeared confusing. While it’s possible Trump was orchestrating some strategic plan behind the scenes, from an outside observer’s perspective, it seems some foreign policy actions weren’t as well-coordinated as they could have been. That said, in the broader scheme, the first Trump administration doesn’t resemble anything like what we saw under LBJ, much less during the Cultural Revolution. It’s important to maintain this comparative reference point.

Jordan Schneider: What about in Trump’s second term?

Tyler Jost: It’s early days. Trump hasn’t revoked the National Security Council. He may have established some parallel structure behind the scenes that we’re unaware of, similar to the Tuesday luncheon, which would send signals to the bureaucracy with a chilling effect even at the highest levels. Within the framework of the book, which focuses on high-level institutional interactions between leaders and bureaucracy, it’s difficult to ascertain from the outside how much Trump has pushed things even in the direction of LBJ.

Warning signs exist, however. The reorganization of USAID is particularly informative to people within the bureaucratic establishment. To be fair, having a Foreign Ministry or Department of State oversee USAID’s responsibilities isn’t unheard of. Placing their personnel within the State Department isn’t outlandish. It’s entirely reasonable for a president to have a foreign policy agenda that curtails foreign aid distribution.

Whether we agree with that policy is separate from how it affects the decision-making process. The means, process, and scope of organizational change bound up in the USAID actions represent the biggest warning sign. We shall see what unfolds in the coming months and years.

Jordan Schneider: I take your point, Tyler, about it being early days on the bureaucratic reorganization front. However, you can also examine the personnel perspective regarding the types of senior advisers now in place, which presents a very different complexion than what we saw in Trump’s first term and feels more like late Mao than early Mao.

Tyler Jost: That’s a fascinating point. The book doesn’t focus centrally on appointing loyalists versus experts, but other areas of political science address that trade-off. They don’t necessarily conceptualize institutions as I did — they think more in terms of hiring criteria, whether it’s credentials for the job or absolute fealty to the leader. It’s an analogous political problem.

The book can’t speak as directly to this question, making it somewhat more difficult to apply the framework to the first versus the second Trump administration along this dimension. Nevertheless, it’s an important question we should continue to monitor.

The “red versus expert” debate is simply one way of articulating the standard expertise-versus-loyalty trade-off that many economists and political scientists have discussed. Some people think this debate is unique to China, but while the formulation may be uniquely Chinese, this represents a perennial political problem.

Jordan Schneider: It’s an LBJ issue, too — he didn’t want people leaking. What do you gain and lose by leaning “red” or leaning “expert”?

Tyler Jost: You can think about this issue in both functional and strategic terms. In the functional sense, imagine a stylized model where you have two candidates. One possesses all the indicators and benchmarks suggesting they’ll excel at the job. The other lacks those attributes but demonstrates complete loyalty — they’ll do exactly what you want once in office.

Often, these indicators aren’t so stark, and typically, you seek people with elements of both qualities. But keeping the model simplified — from a functional perspective, if you choose the candidate without expertise (defined by indicators of job performance), you’re reducing government capacity. You’ve screened candidates solely on loyalty rather than competence, limiting their ability to perform effectively.

The strategic dimension requires more nuanced thinking. Imagine both candidates secure positions and face choices about how to perform their duties and what risks they’ll take to advocate for what they believe is right. The candidate with strong performance credentials has something to fall back on when speaking truth to power. They can justify diverging from the leader’s view because they have experiences underpinning their judgment.

Contrast this with the candidate chosen solely for political loyalty. They have little foundation except the leader’s trust in their allegiance. This fundamentally shapes how they seek information. They’ll likely pursue data confirming what the leader wants to hear and demonstrate risk aversion in identifying new developments in the international environment. This leads to those bland, vanilla reports characteristic of fragmented institutions.

Jordan Schneider: It’s a leveraged bet on the leader’s gut instinct — if you go more “red,” you get more of the leader in whatever policy emerges, for better or worse.

Tyler Jost: Precisely. The book was inspired by a wave of political science literature examining how individual leaders shape foreign policy — something that captured my imagination in graduate school. Where my analysis intersects with this approach is recognizing that when institutions tear away the connective tissue between leaders and the bureaucracy, foreign policy increasingly shows the leader in absolute terms. This isn’t necessarily beneficial — that’s the twist my book offers. Only when institutions incorporating bureaucratic perspectives are established do outcomes begin to look substantially different.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s conclude with Xi. We discussed the post-Xi era, but let’s talk about Xi himself. How is he handling all this?

Tyler Jost: We should be even more cautious about drawing inferences regarding Xi than with Trump because the information environment is quite poor. I’ll make two points.

First, I’m reasonably convinced Xi Jinping inherited those middle-ground siloed institutions I described — the hub-and-spoke model where information reaches the leader but with limited horizontal sharing between bureaucratic actors. This conclusion stems partly from the system’s own statements justifying institutional changes they implemented, such as establishing the National Security Commission early in Xi’s first term.

Some argue that these institutional reforms solved all problems, but I’m skeptical for several reasons. The National Security Commission essentially renamed its predecessor, the National Security Leading Small Group, signaling Xi’s political power — similar to Joseph Torigian’s argument about Deng Xiaoping pushing for war with Vietnam as a power demonstration. But the composition of these groups didn’t change substantially. Additional staff may have been added, but public reporting indicates the National Security Commission has focused more on domestic issues than international security problems.

What made the system “siloed” when Xi took office was primarily the segregation of military decision-making via the Central Military Commission from the civilian bureaucracy. That division between these two systems remains the most prominent feature of what Xi inherited. His response hasn’t been to integrate the military with civilian bureaucracy at lower levels. Instead, he appears to have doubled down on direct, unilateral control of the military through the Central Military Commission. This gives him more control but at a cost — it allows the military to channel information directly upward without vetting by other bureaucratic elements.

Second, we might ask whether the system has deteriorated under Xi. Unlike the Cultural Revolution, where systemic changes were obvious to outside observers, the formal structures of decision-making haven’t undergone a dramatic transformation. However, the dismissal of minister-level positions in the Foreign Ministry and military apparatus operates at a different level — focusing on personnel rather than institutions. This likely creates a chilling effect. Lower-level bureaucrats report fear of speaking truth to power, which isn’t surprising.

We must be careful about these inferences, though. Most indications of the chilling effect from Xi’s anti-corruption campaign and personnel decisions come from very low levels. What remains unclear, at least publicly, is how the bureaucracy interacts with political leadership — the primary focus of my book, which argues this is the most important area to examine. We don’t know if the same fear of speaking truth to power shapes those higher-level interactions. It may be some time before we can conclusively characterize decision-making under Xi’s system.

Jordan Schneider: From a Western policymaker perspective, given these new uncertain variables about how information travels upward, what should officials be thinking or doing differently if they might be in this complicated situation rather than a clean information environment?

Tyler Jost: This is an important question with both assessment and strategy components — what we should think and what we should do.

On the assessment side, we should incorporate into our calculations the possibility that Beijing may develop a completely different perspective on the international environment. This could result from Xi Jinping’s independent judgment or from judgments based on the information presented to him, combined with his personal understanding of the situation.

Regarding strategy, the challenge is substantial. It requires a two-step approach: first, identifying early signs of misperception forming on the Chinese side; second, attempting to correct that misperception. However, if the institutional structures themselves are causing China to develop misperceptions, then direct interaction with the leader may be the only effective channel for shaping their worldview.

If the bureaucracy won’t transmit quality information for any of the reasons we’ve discussed — whether related to personnel, institutions, or other factors — then lower-level interactions won’t be effective. Military demonstrations, actions in the South China Sea or Taiwan Strait, export controls — all these signals get filtered through the bureaucracy in ways that may prevent belief changes at the top. This forces us to consider that altering beliefs on the Chinese side might require direct interaction with the Supreme Leader, making face-to-face diplomacy one of the few means available to meaningfully influence the situation.

“We Were Wrong, Terribly Wrong”

Jordan Schneider: Tyler, across all your case studies, is there one moment or meeting you wish you could have witnessed firsthand?

Tyler Jost: Probably all of them. There’s the meeting in fall 1961 with Nehru and his advisors, where foreign policy was pushed to its limit. There were meetings in January, February, and March in Beijing between Mao and his subordinates that led to the Sino-Soviet border clash.

There’s also January 29, 1965 — the date when the “Fork in the Road” memo was drafted primarily by Bundy and McNamara and delivered to LBJ. I believe they met that same day. While different theories exist about the true turning point of the Vietnam War, my personal assessment, as presented in the book, is that this was the decisive moment. It would have been fascinating to witness these meetings firsthand.

Jordan Schneider: Can we discuss how terrible that memo was? It was high school-level, B-minus work. It’s embarrassing.

Tyler Jost: What’s interesting is that, unlike the Iraq War generation of American leaders who maintained until their deaths that they did nothing wrong, the Vietnam era advisors were deeply troubled by what happened. McNamara states in his memoirs that, “We were wrong, terribly wrong.”

McGeorge Bundy, who didn’t publish memoirs but left a draft available in the Kennedy Library in Boston, makes two points. First, he acknowledges that communism in Asia could have been contained at much lower cost than the escalation in Vietnam — undermining the rationale that motivated him. Second, he identifies his greatest mistake as National Security Advisor as the shallowness of analysis he provided to LBJ, which is remarkable since that was his primary responsibility.

Bundy understood this was his job, particularly from his years with Kennedy. However, Johnson’s choices made it difficult for advisors like Bundy and McNamara to perceive the situation accurately. Bundy, in particular, was a hawk, so Johnson’s system allowed the analysis to excessively reflect Bundy’s personal perspective. This bias is evident in both the memo we mentioned and in several others Bundy wrote the following month, most notably after the attacks at Pleiku.

Jordan Schneider: It’s fascinating that these Vietnam era officials didn’t gaslight us, while the Iraq War ones maintained their positions until death. My assumption is that the independent variable is 58,000 versus 4,000 American military casualties. There’s an undeniable truth to that number and a shock to the societal fabric that might not have seemed as important when compared to Korean War, World War II, or World War I death tolls.

Vietnam crossed a threshold of public awareness in the US.

That factor, combined with the definitive way the war ended, made a difference. By the time Rumsfeld died, we had ISIS in Iraq, but the outcome remained somewhat unresolved, unlike in Vietnam where the Viet Cong clearly took over the country.

Tyler Jost: You should consult some of my colleagues who have studied the Iraq War in depth. This comparison between Vietnam and Iraq officials is an interesting point about the independent variable. I’ve used this comparison multiple times without explaining the difference. What strikes is how unusual it is for advisors to admit they made mistakes in the decisions they were most responsible for. This tells us something important was happening in the lead-up to Vietnam.

Of course, other explanations exist. There are more self-interested interpretations where they might have been trying to salvage their reputations. At certain points in his memoir, McNamara’s analyses about why they were wrong seem completely misguided. For example, he claims the US had extensive expertise regarding the Soviet Union but none regarding Southeast Asia. This is objectively false.

The problem wasn’t a lack of experts in the State Department or National Security Council. The problem was that when these experts wrote memos to be sent to the President, officials like McNamara blocked them, saying, “No, absolutely not. This isn’t going anywhere.” McNamara did this for specific reasons, and we can understand why he acted as he did.

Tragedy appears in the opening lines of my book. These events are tragic and with the benefit of hindsight, one wishes things had been different. The cold reality is that these outcomes are so firmly rooted in politics that even if we hope decision-makers would rise above such forces, politics remain powerful enough to ensure these patterns will continue perpetually as a result of contestation between political actors.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s close with your opening lines then:

“One of the tragedies of international conflict is that it often achieves so little. History is replete with examples of states charging headfirst into international confrontations that left them no better off and often much worse off than where they started.”

Here’s to hoping.

I enjoyed the mix of history, political science, and behavioral economics in this framing

This conversation was interesting enough that I will be buying Professor Jost's book. Thanks for the fascinating interview.