China’s AI Landscape: a free-for-all, not a central plan

what 6000+ filings with regulators reveal

Zilan Qian is a programme associate at the Oxford China Policy Lab and holds a Master’s degree in Social Science of the Internet from the University of Oxford.

The dominant narrative about China’s AI race frames it as a government-backed sprint toward AGI capabilities, competing head-to-head with the US frontier. But examining more than 6000 records of generative AI models filed through China’s registry system (updated through November 2025) tells a different story.

Since 2023, all public-facing AI models must be filed with regulators before launch — creating an unprecedented window into China’s actual ecosystem. China’s AI registry system creates multiple datasets organized by service type and regulatory concern: internet information service algorithm (IISA), deep synthesis algorithms (DSA), and generative AI services (also known as AIGC, AI-generated content). This article draws on AIGC and DSA datasets — the ones capturing generative AI development — while leaving aside IISA data, which focuses on non-generative technology like recommendation algorithms.

In this piece, I focus on quantitatively analyzing the records in the registry system, which challenges the “AI race” narrative where China as a whole is tightly united under central government guidance. Instead, the analysis will show that:

Private companies, rather than the state, drive development

Frontier developers are pursuing specialized models rather than converging on a single path for scaling LLMs

Geographic concentration reveals local governments actively shaping innovation clusters through fiscal competition.

For a comprehensive look at the development of China’s AI regulations into a formal registry system, I have prepared a full explainer. This analysis covers the system’s key focus areas, the types of AI content regulators seek to censor, and the processes used for conducting broad security assessments of AI services. I believe this explainer offers valuable insights for China watchers, as well as AI governance and safety researchers, by detailing the strengths and weaknesses of China’s approach to AI registration.

Understanding the Data

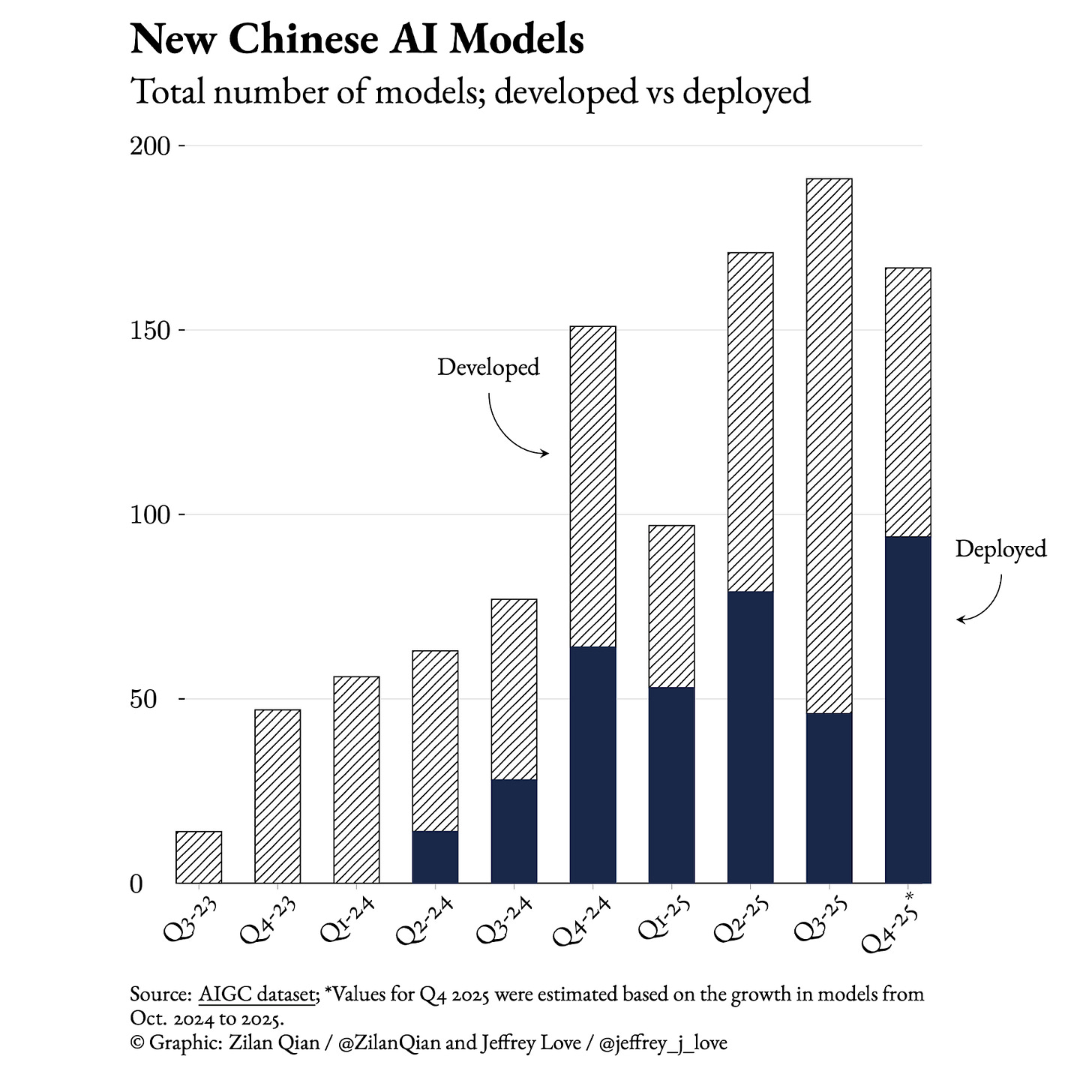

The AIGC dataset tracks all new public-facing AI models developed in China, showing who is building what, where, and when. It captures two types of activity: models being developed (training from scratch or fine-tuning open source models) and models being deployed (using APIs of China’s models or locally installed open source models without modification). Together, these reveal both the landscape of model development and how quickly models reach actual users.

The DSA dataset captures the specific algorithmic services for the public that are built to generate content — text, images, video, and audio. Here, the focus is on major AI developers to show where China’s frontier AI is concentrating its technical capabilities and commercial strategies.

In a nutshell, the AIGC dataset answers the question, “What major AI models exist in China and who built them?” while the DSA dataset answers, “What specific generative algorithmic functions are frontier companies building?” Together, they provide both a landscape view (AIGC) and a technical functionality view (DSA) of where China’s AI development is concentrated.

Three important caveats:

First, both datasets track general model families rather than individual versions. Whether it’s DeepSeek V3 or R1, they all register as a single “DeepSeek” entry when it is first filed in the system. Although DSA filing was intended to track AI model updates, in reality, only a few developers refiled their model updates between 2022 and 2023. In general, AI model version updates are invisible.

Second, China’s registry system is designed to monitor AI’s impact on public discourse and social stability within China, so it captures only part of the ecosystem. Internal corporate AI deployments, non-public R&D (e.g., military), and overseas operations fall outside this system.

Third, the filing-to-registration process typically takes 2-5 months, but can vary significantly on a case-by-case basis. This means dates shown below don’t perfectly align with actual development or deployment dates (rather, they’re more often ~3 months late).

Private Sector Leadership with Accelerating Deployment

It is not a surprise to see the total number of AI models in China growing. The deployment of existing models has steadily increased between 2023 and 2025, suggesting that more adoptions have happened on the ground. Meanwhile, although we do not observe a skyrocketing surge in China’s AI model development based on the number of models filed, we should remember that the system does not account for model updates. In other words, although frontier AI companies are fiercely competing to roll out updated models — like DeepSeek-R1/V3.1/V3.2, Qwen-3/3-Omni-Flash/3-Coder/image, Kimi-K1.5/VL/K2, and more in 2025 — these models are not in the registry. In the registry, they simply show up as three entries: DeepSeek, Qwen, and Kimi. Thus, real model development is far more active.

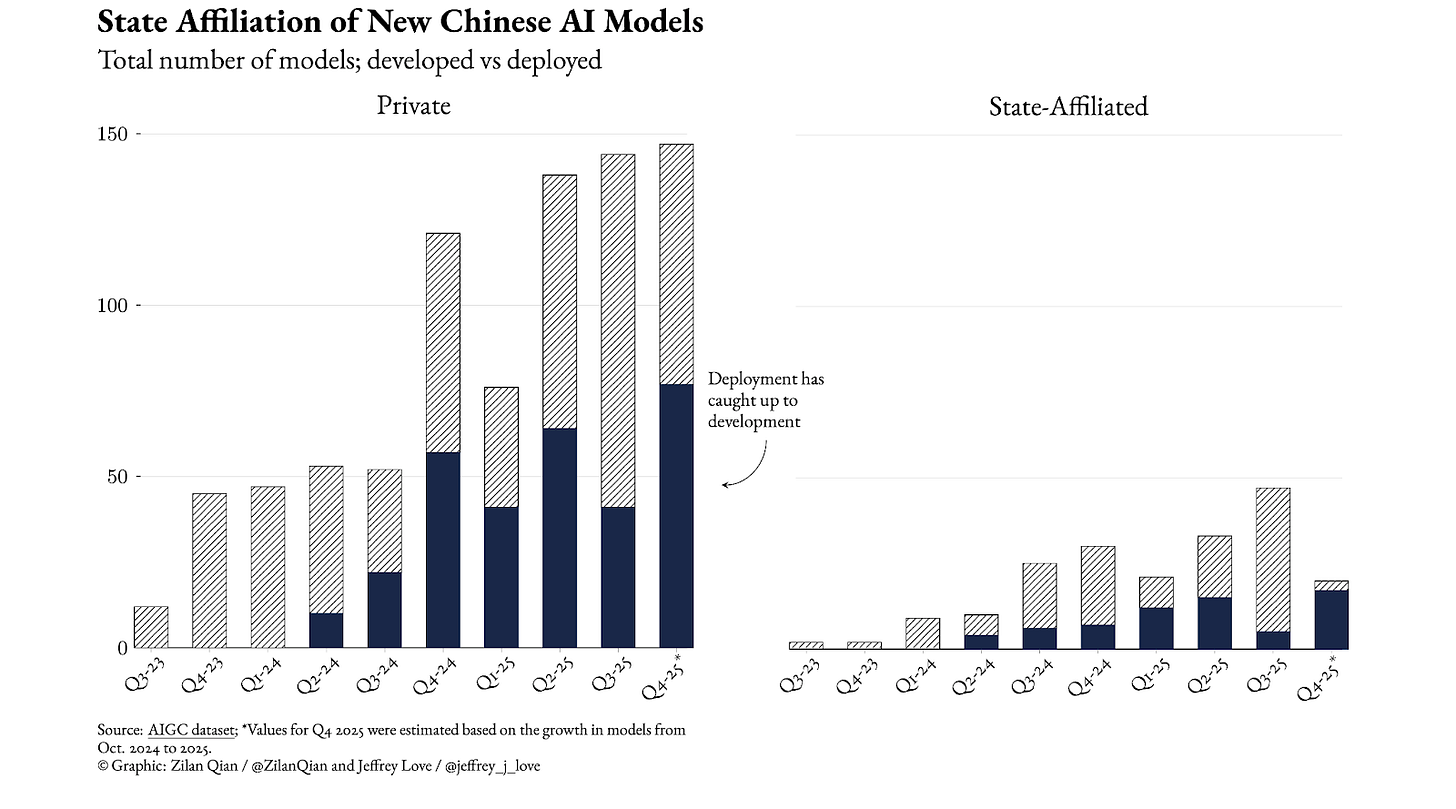

Zooming in on the developers and deployers of AI models, we see that private companies have consistently dominated both model development and deployment since 2023, including big names in AI like Alibaba, top performers in non-AI markets like the education giant TAL (好未来教育集团), as well as a few foreign entities like Tesla. This dominance shows no sign of reversing. Even as state actors — such as telecommunications companies and state-owned research labs — have become more active, they remain secondary participants in overall model development.

Meanwhile, two development and deployment timing patterns deserve attention. A noticeable surge in developments and deployments occurred roughly six months and three months respectively after DeepSeek-R1’s release in January 2025 — the state’s review process of deployment usually takes 2-3 months, and 2-5 months for developed AI models. The AI model has to be fully developed before it can be submitted for review by regulators.This pattern is consistent with reports of companies rushing to deploy DeepSeek to capitalize on market momentum, as well as with AI developers rushing to roll out new models to compete with R-1.

Where does the state enter?

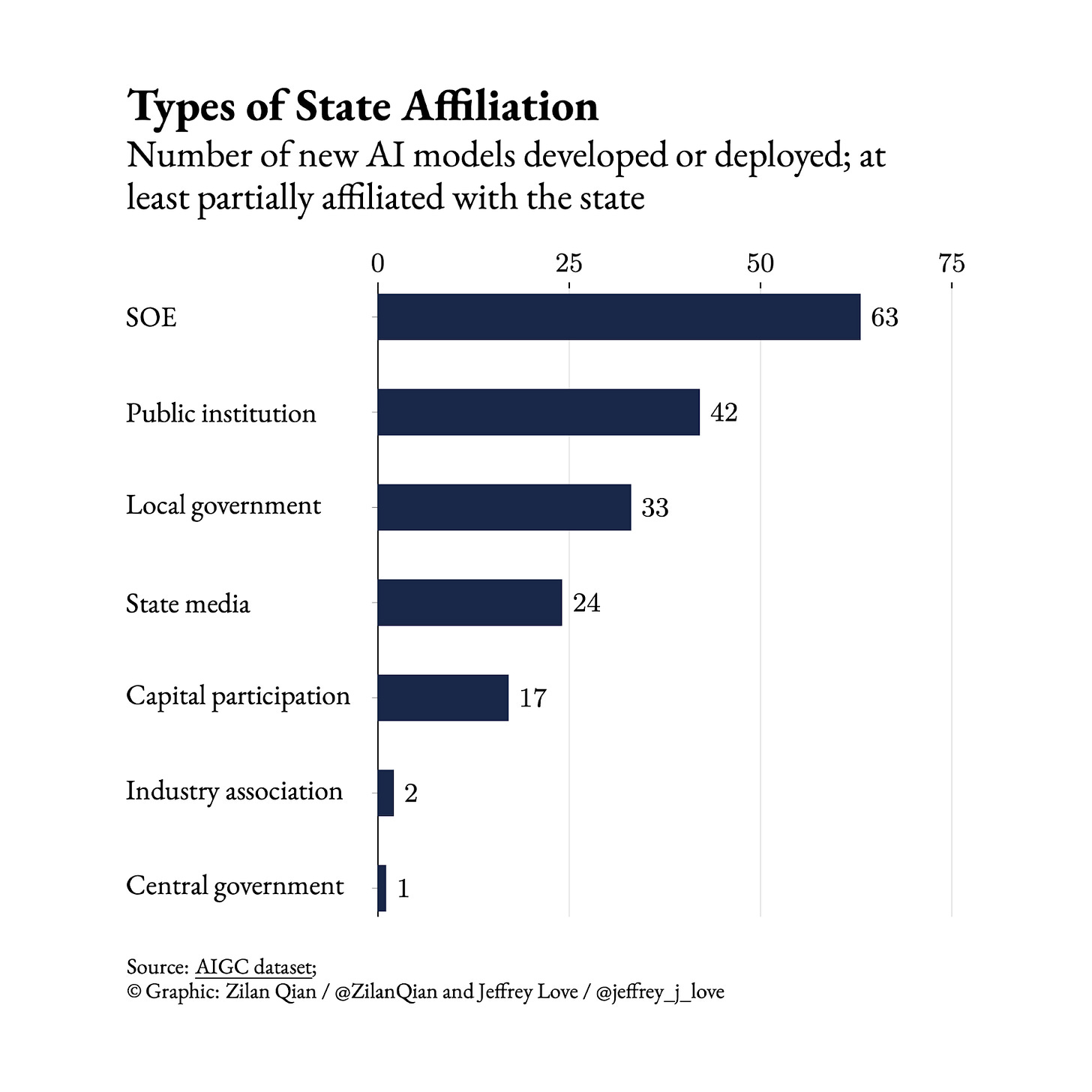

State-affiliated actors are increasingly visible on the registry. While not primarily competing for frontier model capabilities, they’re building what appears to be infrastructure and application layers.

State-owned enterprises are the most active government participants, particularly China’s two major telecom operators — China Mobile (中国移动) owning 3 models, China Telecom (中国电信) with 5 models, and the IT conglomerate Inspur group (浪潮) with 7 models. These companies traditionally dominated China’s digital infrastructure.

Beyond SOEs, universities and public research institutions are filing models, as are central and local government and state media outlets. Here, some prominent universities and labs — like Shanghai AI Lab — are building general-purpose AI, but more are building vertical AI models. For example, Tongji University’s College of Civil Engineering developed “CivilGPT” tailored toward their discipline, and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Information Center built “China-ASEAN Legal LLM (中国-东盟法律大模型)” for legal coordination and mutual recognition between China and ASEAN countries.

Meanwhile, state-affiliated institutions are also actively deploying AI for very specific use cases. One major deployment scenario is customer services/general Q&A, with five AI medical assistants thus far deployed by public hospitals, and seven AI customer service assistants deployed by state-controlled banks. Meanwhile, there are only three entries that resemble AI agents — one from Inspur, one developed to assist with the World AI Conference, and another by Great Wall Motors 长城汽车, in which the state holds only limited stock (~8%).

The participation suggests a decentralized approach where state-affiliated institutions are developing vertical AI in specific domains that are ignored by private companies. While deployment spans various public-facing sectors like healthcare and finance, the integration of AI remains limited to narrow functions like AI chatbot assistants. This indicates that, up until 2025, state actors were still scratching the surface rather than attempting comprehensive sectoral digitalization as outlined by the State Council’s AI+plan.

General-Purpose LLMs are not the only way: What are China’s frontier developers building?

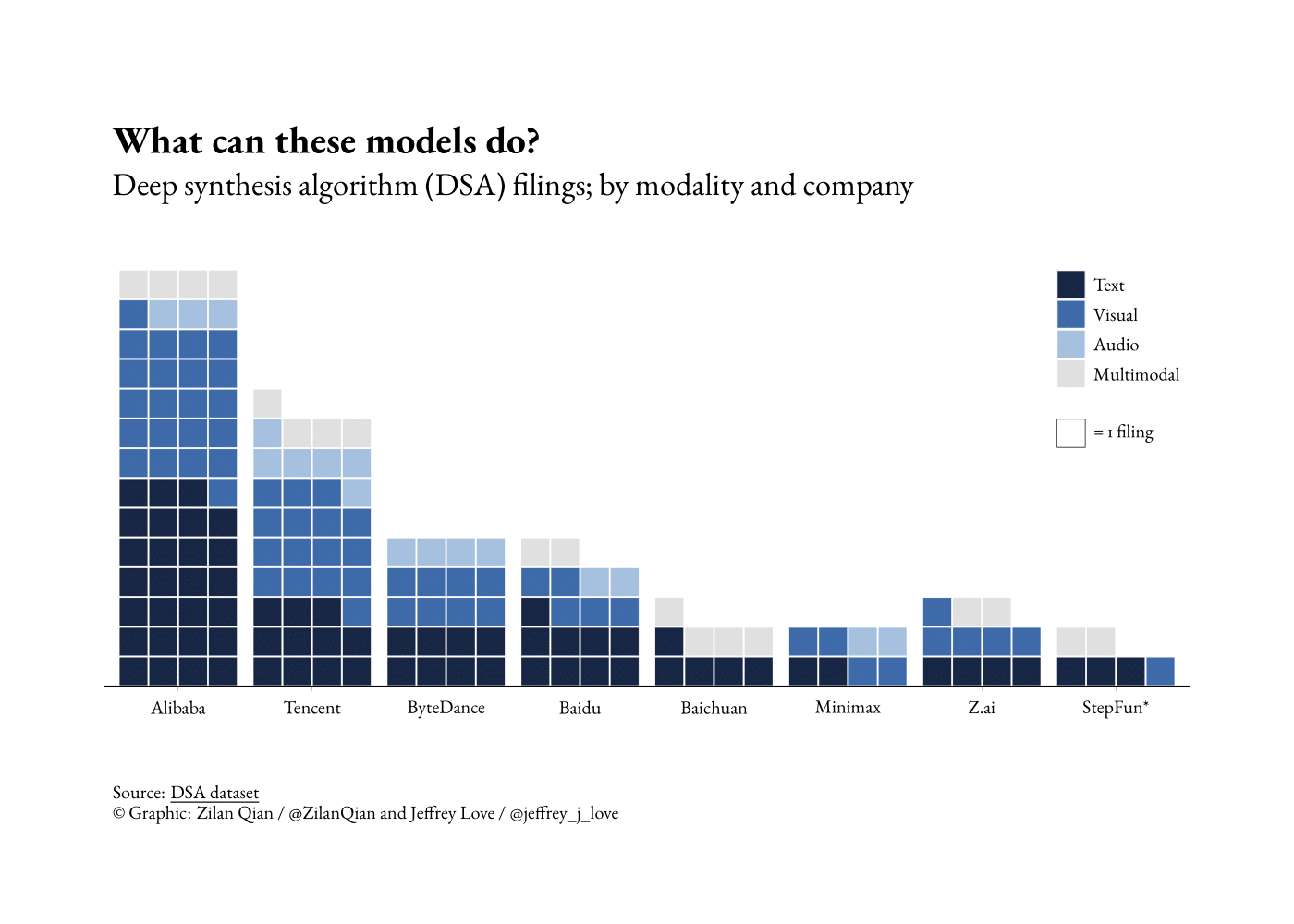

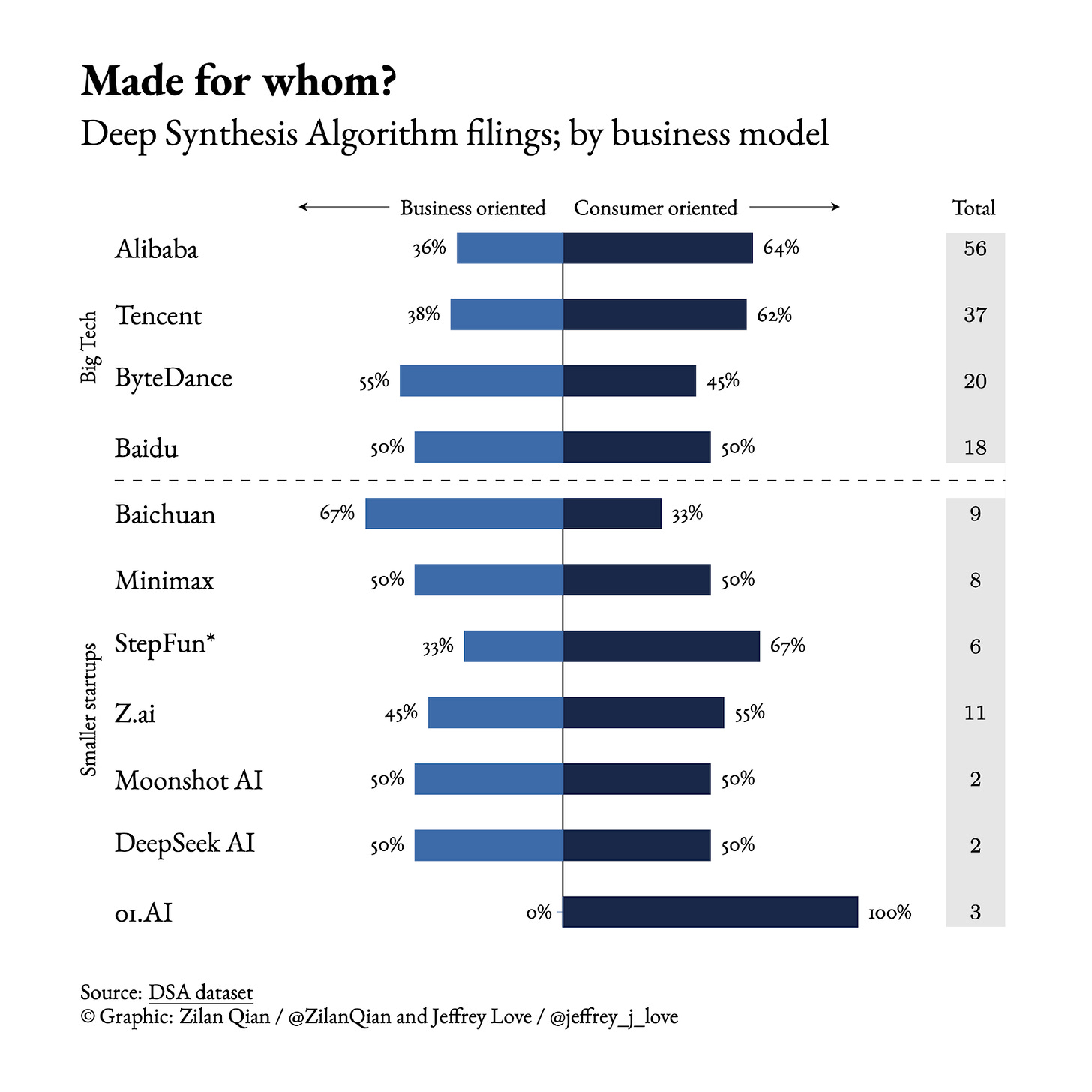

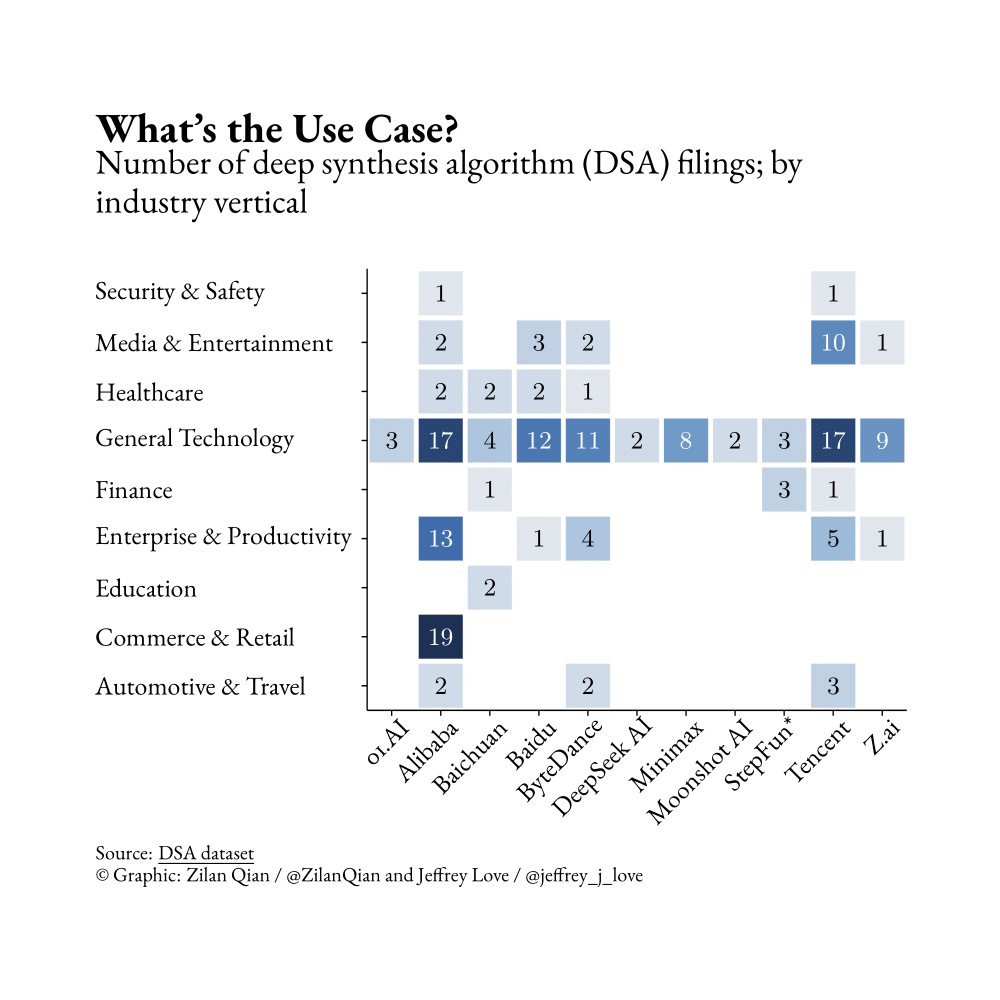

Generalist developers like DeepSeek and Moonshot have built large general-purpose models focused specifically on text generation — and the founders of DeepSeek and Moonshot have both publicly discussed AGI as a long-term vision. But this is a minority position among frontier developers. The dominance of text-only LLMs in public discourse masks a much more diversified market where most developers are optimizing for specific commercial applications rather than frontier capabilities.

Big tech companies pursue broader strategies. Alibaba dominates in use-case breadth, with filings spanning general technology, enterprise, commerce, and media. ByteDance, Baidu, and Tencent similarly spread across multiple sectors — all of these players have at least one filing in enterprise and productivity tools. In general, their filings seem concentrated on applications with immediate commercial value and clear deployment paths. Here, we also see that some big tech companies are leveraging their traditional strengths. Alibaba — as the owner of e-commerce giant Taobao (淘宝) — prioritizes e-commerce and retail, while Tencent — operating multiple video streaming platforms and popular video games — focuses on entertainment.

Moreover, Alibaba and ByteDance are actively integrating multiple AI tools into their respective legacy platforms. Alibaba, for instance, has deployed AI services across its e-commerce platform Taobao, its food delivery service Ele.me (饿了么), and its workplace tool Dingtalk (钉钉). Similarly, ByteDance has integrated AI into its workplace productivity platform Lark (飞书) and its short-form video app Douyin (抖音). This pattern reveals a strategy where AI is built for existing platforms and customer bases, alongside selective standalone new AI products (such as ByteDance’s Doubao 豆包 chatbot and Alibaba’s AI-enabled browser Quark 夸克) .

On the other hand, lacking traditional platforms, smaller startups allocate their focus more narrowly, often on general models or specific verticals in healthcare or finance. MiniMax and Z.ai, which own the highest numbers of DSA records in general technology among all startups, have already IPO-ed in Hong Kong.

Beyond text-focused LLMs and multimodal LLMs, companies are registering AI products specialized for video, image, and audio generation. Virtual human (数字人) generation is particularly common — and in fact is offered by all four major big tech companies — which suggests that virtual hosts are perceived as a significant commercialization opportunity in the livestreaming industry.

Multimodality not only supports integrated virtual human-AI interaction, as seen in AI companions or disability assistance. Rather, multimodal AI is also increasingly combined with physical manufacturing to create real embodied intelligence, as demonstrated by the recently-announced collaboration between MiniMax and Zhiyuan Robotics 智元机器人 to build multimodal AI robots that are conversational and customizable.

Overall, this diversification in both technical approach and target market — from enterprise tools to entertainment to vertical domains — reflects a strategy optimized for deployment and integration rather than frontier capability racing.

Almost all frontier developers engage in a relatively balanced split between business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-customers (B2C). Although 01.AI’s existing AI services were initially B2C-focused, they have transitioned into B2B services since early 2025, mainly using DeepSeek to help build companies’ workflows. Because the registry system focuses on public-facing AI, highly specialized or internal B2B services (serving a single company rather than multiple clients) do not appear in the records, so the actual B2B proportion in the market is likely larger than the data suggests.

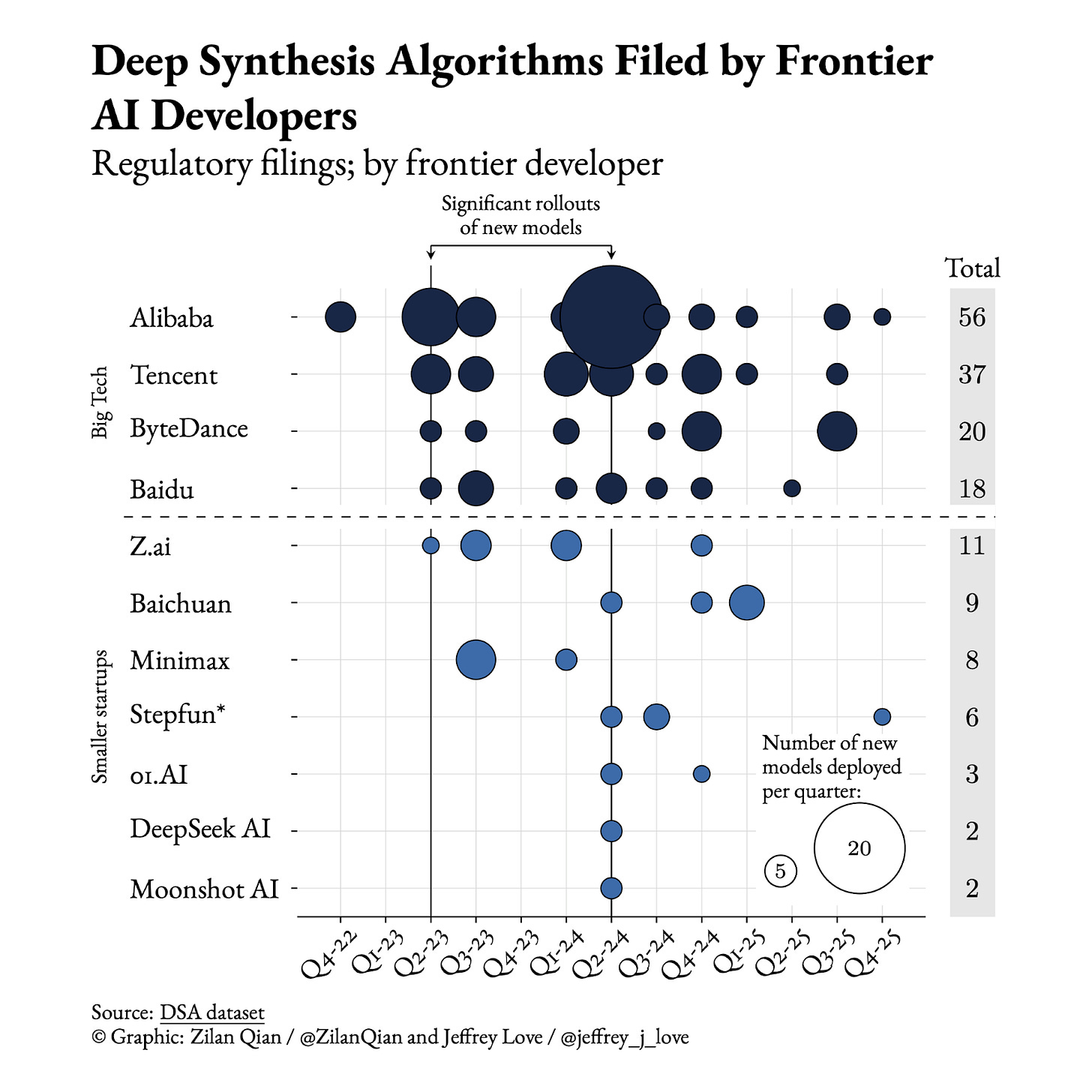

Timing also reveals something about market dynamics. Alibaba began to launch generative AI services in 2022, the earliest among major players. Z.ai and MiniMax both filed models nearly a year before other startups, suggesting technological readiness and regulatory savvy that put them ahead of peers. A possibly state-coordinated influx of developers entered the market in mid-2023. Most other frontier developers entered the filing system in mid-to-late 2024, clustering around the time after generative AI became commercially viable and more visible in China.

By 2025, new model filings from frontier developers have slowed — likely reflecting consolidation rather than stagnation, given dataset limitations around tracking updates and internal iterations. The rise of DeepSeek turned China’s private sector competition from a quantity-based game into one of quality. As frontier developers have established flagship foundation models, the focus in 2025 was primarily on improving model capabilities — and those initiatives are invisible according to this registry system. While competitions in the frontier will still be a priority in 2026, these developers, especially big tech companies, may increasingly focus on turning AI capabilities into useful applications for the market.

Geographic Concentration: Where Policy and Innovation Intersect

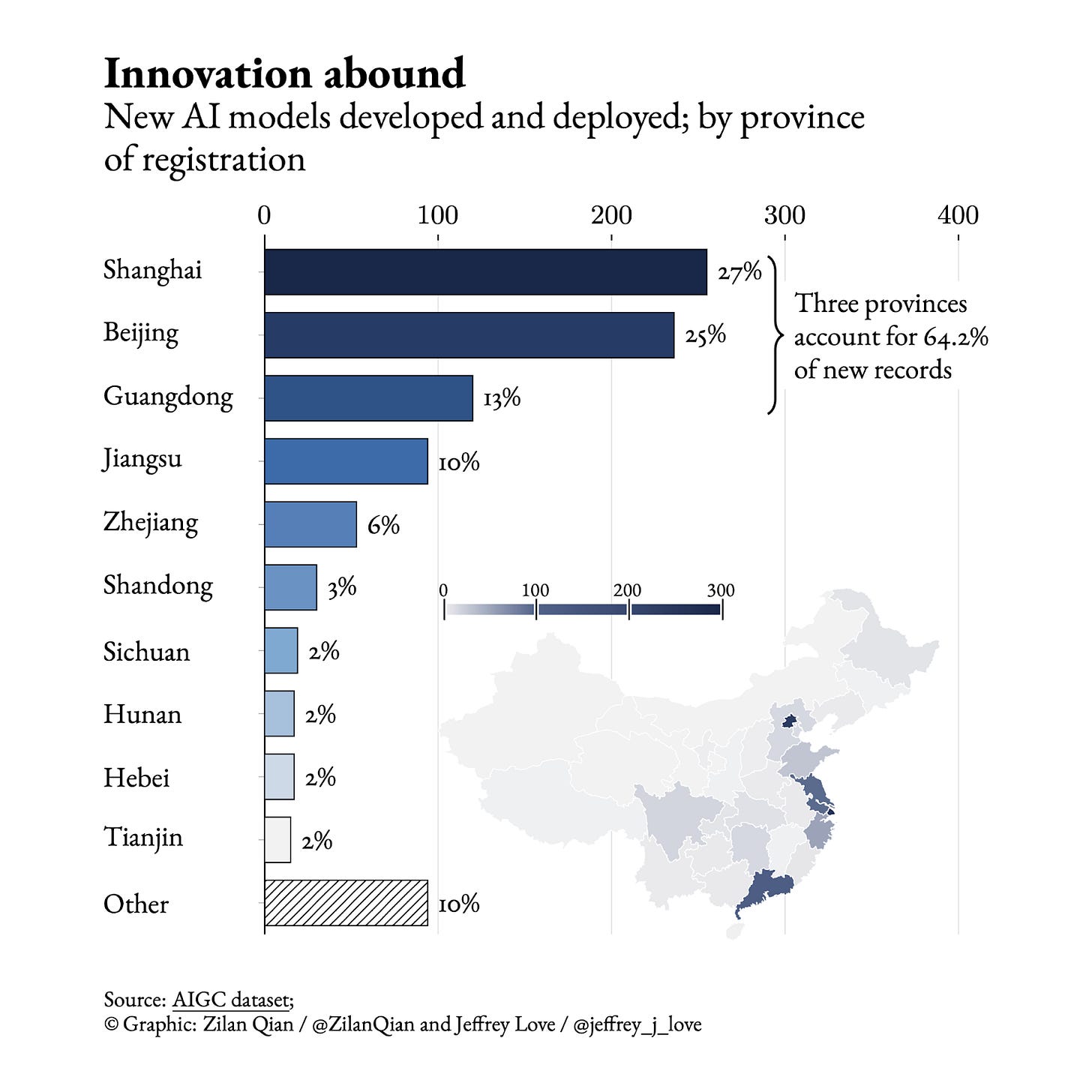

The most striking pattern in the data is geographic: five provinces account for over 80% of all model development and deployment, with the top three representing over 60%. It’s clear that Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong (including Shenzhen), Jiangsu, and Zhejiang have become the dominant centers of China’s AI ecosystem.

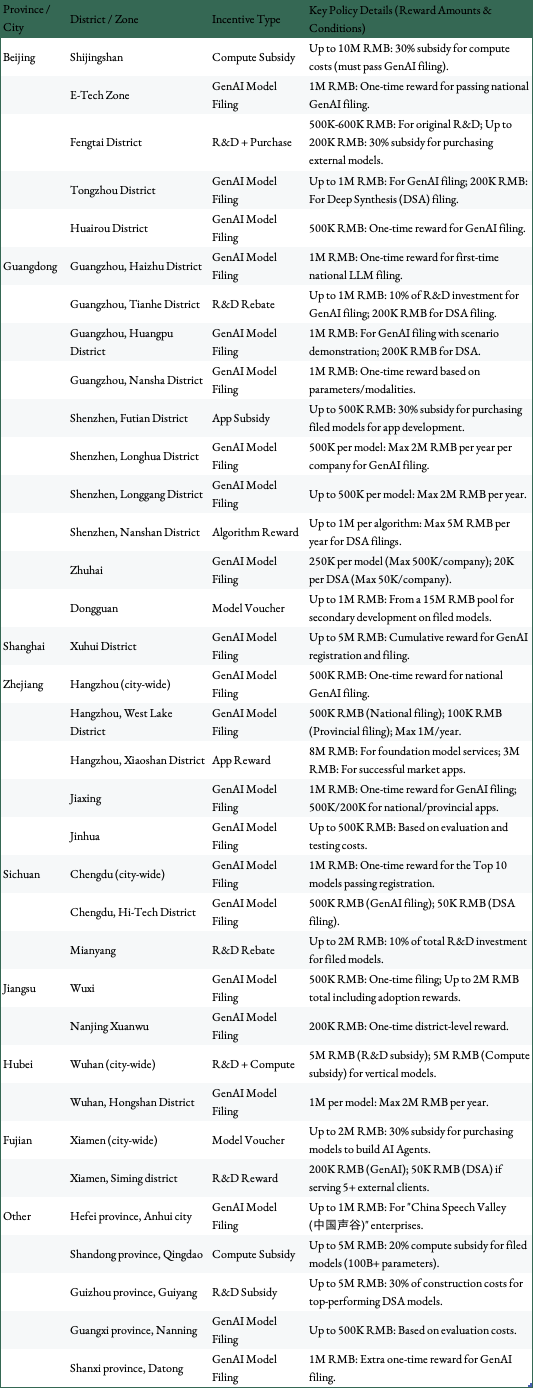

This pattern is not accidental but instead aligned with the uneven economic foundations and concentrations of talent in China. District or city-level governments in these dominant regions, which tend to have greater fiscal capacities, have established explicit subsidy programs to encourage AI development and deployment. Shanghai’s Xuhui District increased rewards from 2 million RMB (~US$286,000) to 5 million RMB (~US$715,000) between 2023 and 2025 to maximize AI model filing. Hangzhou offers 50 million RMB (~US$7.1 million) for foundational models trained on 10B+ tokens. Dozens of cities across these five provinces offer one-time rewards ranging from 500,000 RMB (~US$71,500) to 5 million RMB per filing.

These aren’t trivial sums in an early-stage AI economy. DeepSeek-R1’s training cost was estimated to be less than $300k. Although that figure discounts compute cost, we also observe that multiple local governments offer “compute vouchers (算力券).” Meanwhile, MiniMax reported spending ~US$535k renting the data center computing resources needed to train M1. After all, a 1-5 million RMB incentive (~US$143k to ~US$715k) is substantial enough to influence where companies choose to operate and whether they prioritize getting models into the formal registry system. More developed regions can offer the highest subsidies, and thus show the highest density of AI filings.

Today in China, many local governments cite the number of AI models developed and deployed locally as a proxy for innovation or competitiveness. But these figures are also capturing the effect of local fiscal competition. Some entries represent genuine technological breakthroughs, but perhaps some are merely geographic arbitrage in response to government incentives. One should be cautious about over-indexing on these numbers — they should not be treated as s metrics of pure innovation. Not every model is DeepSeek.

The subsidy structure also reveals how China actually governs innovation in practice. China represents a hybrid model, rather than a system relying on central planning or market forces alone. Local governments compete to attract and retain AI development activity through fiscal incentives, creating a decentralized innovation ecosystem shaped by regional competition. This produces unequal outcomes (five provinces dominating) but also creates a system where innovation is geographically embedded in local economic strategies rather than concentrated in a single national hub.

Decentralized Growth and Private-Driven, Internal Competition

Taken together, these patterns suggest China’s broader AI ecosystem operates according to a different logic than the “US-China AI race” framing suggests.

First, development and deployment remain private-led, with state participation filling infrastructure and application gaps rather than competing directly for frontier capabilities. Despite the existing rhetoric of central top-down coordination of AI to race against the US (or SOEs and local governments frantically participating in the AI race after DeepSeek), the real systemic structure, characterized by the dominance of private companies, remains relatively steady over the years.

Second, frontier developers are pursuing diverse technical and commercial strategies rather than converging on LLMs as the path to AGI. The data shows specialization in modalities, vertical domains, and applications. This reflects a market where companies are optimizing for deployability and commercial viability, not just pushing frontier capabilities.

Third, China’s AI ecosystem is being actively shaped by local policy competition and fiscal incentives, not purely by market forces or by central planning. This creates geographic inequality but also reveals how innovation actually gets governed in practice through decentralized competition for activity and talent. It also raises concerns of potential resource waste, especially given that many local governments are currently short of money.

None of this means China isn’t building powerful AI capabilities. The registry shows significant activity, rapid deployment, and participation from major economic actors. But it does suggest the ecosystem is being built differently than headlines about “AI race” competition would imply: less centralized, more commercially focused, and shaped as much by regional policy competition as by centrally-driven technological ambition.

Acknowledgements:

This reporting was supported by a grant from the Tarbell Center for AI Journalism. Zilan is grateful to Tarbell for the editorial independence to pursue this research. Zilan also wants to thank Jack Love for his excellent graphic design assistance, and Kayla Blumquist and Karuna Nandkumar for their thoughtful review and feedback.

This analysis was inspired by Trivium China’s reporting on China’s AI landscape, and the AIGC dataset builds partly on their earlier work. Due to the constraints of time and manpower, the two open-sourced datasets are not perfectly cleaned and may miss some data points. Please feel free to revise and build on top of the data.